Abstract

Electrostatic interactions play a pivotal role in enzymatic catalysis and are increasingly modeled explicitly in computational enzyme design; nevertheless, they are challenging to measure experimentally. Using vibrational Stark effect (VSE) spectroscopy, we have measured electric fields inside the active site of the enzyme ketosteroid isomerase (KSI). These studies have shown that these fields can be unusually large, but it has been unclear to what extent they specifically stabilize the transition state (TS) relative to a ground state (GS). In the following, we use crystallography and computational modeling to show that KSI’s intrinsic electric field is nearly perfectly oriented to stabilize the geometry of its reaction’s TS. Moreover, we find that this electric field adjusts the orientation of its substrate in the ground state so that the substrate needs to only undergo minimal structural changes upon activation to its TS. This work provides evidence that the active site electric field in KSI is preorganized to facilitate catalysis and provides a template for how electrostatic preorganization can be measured in enzymatic systems.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Electrostatic stabilization has been widely discussed as an important feature that endows enzymes with their signature high catalytic proficiencies.1–9 One (simple) way to frame this hypothesis is that enzymes create a particular electrostatic environment in their active sites, which preferentially stabilizes the charge distribution of the transition state (TS) more than the ground state (GS) to accelerate the reaction4

| (1) |

where is the reactant’s dipole moment, is the transition state’s dipole moment, is the electric field the environment exerts on the reactant dipole, and is the electric field the environment exerts on the transition state dipole. It should be noted that eq 1 exactly treats the simple case where the substrate is a point-dipole; in more realistic scenarios, ΔΔG‡ is a sum of several terms for each bond dipole that changes during the reaction coordinate in which the fields correspond to the fields projected onto the given bond dipoles at their respective positions.

Conceptually, electrostatic stabilization can be divided into two limiting cases.6 In one case, where the dipole moment of the substrate does not reorient upon activation, preferential stabilization of the TS can be achieved because the magnitude of the dipole moment in the TS is larger than that in the GS, which here we call a scaling effect. In a second case, where the dipole moment of the substrate reorients but does not change its magnitude upon activation, preferential stabilization can be achieved because the orientation of the dipole moment in the TS is better aligned with the electric field of the enzyme, which we call an orientational effect.

Previous work in our lab has demonstrated a significant role of electrostatic stabilization in the catalytic proficiency of the model enzyme ketosteroid isomerase (KSI).1,2 KSI catalyzes the isomerization of 5-androstenedione to 4-androstenedione via a dienolate intermediate with a rate acceleration (kcat/kuncat) of approximately 107.5 (corresponding to a barrier reduction, ΔΔG‡, of 10.2 kcal mol−1), where kuncat is the unimolecular rate constant of an “uncatalyzed” reaction that proceeds through the same nominal mechanism.3,10 An oxyanion hole composed of tyrosine 16 (Tyr16) and aspartic acid 103 (Asp103) in the active site directly interacts with the carbonyl group of the substrate that undergoes a charge rearrangement in KSI’s rate limiting step (Figure 1A upper). Tyr16 is further hydrogen-bonded (H-bonded) with tyrosine 57 and tyrosine 32 to form an extended H-bond network (Figure S1A).11 Using a combination of vibrational Stark effect (VSE) spectroscopy, solvatochromic data and molecular dynamic (MD) simulations, the electric field experienced by the carbonyl group of a TS/I analog, 19-nortestosterone (19NT), was found to be very large when bound in the KSI active site. Moreover, this active site electric field (as probed by the carbonyl group of 19NT) is linearly correlated with the free energy barrier of the catalyzed reaction, ΔG‡, across wild-type KSI and several KSI mutants with canonical and noncanonical amino acid substitutions (Figure S1B).1,2

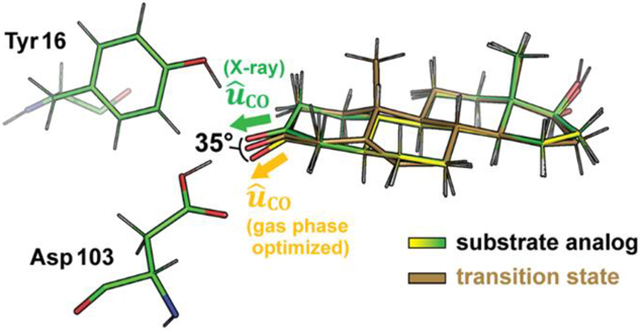

Figure 1.

Electrostatic stabilization in the context of ketosteroid isomerase (KSI). (A) KSI catalyzes the isomerization of 5-androstenedione to 4-androtenedione via a dienolate intermediate. The negative charge on the oxygen in the transition state (TS) and intermediate state (I) is stabilized by the oxyanion hole. As the reaction proceeds from the GS to the TS and I, the hybridization of the C4 carbon (red circle) of the substrate changes from sp3 to sp2. 5α-dihydronandrolone (DHN) and 19-nortestosterone (19NT) are used to mimic the two states, respectively. (B) Ab initio calculations on the substrate, TS, and I of KSI’s reaction in the gas phase suggests electrostatic and geometric changes occur along the reaction coordinate. (C) The electric field of KSI, , preferentially stabilizes the TS because of its larger bond dipole. Furthermore, the angle change shown in part B could result in the C−O dipole in the TS becoming better aligned with leading to additional stabilization. Equation 1 encompasses both the scaling effect and orientational effect of electrostatic catalysis.

In previous work modeling the role of electrostatics in catalysis KSI, we employed the simplifying assumption that the orientation of the substrate’s C=O does not change significantly during KSI’s catalysis and that the (constant) C=O orientation could be modeled with 19NT. In this model, eq 1 simplifies to the following expression

| (2) |

from which one would expect to see a linear correlation between activation barrier and active site electric field. This model assumes that reorientation of the substrate’s C=O dipole upon formation of the TS is minimal and electrostatic stabilization in KSI works entirely through the scaling effect. Under this assumption, VSE measurements showed that the carbonyl bond of the substrate increases in magnitude by 1.1 D upon passage to the TS and electrostatic stabilization contributes to 70% of KSI’s barrier reduction (Figure S1B).1

In the following, we aim to provide a more complete and accurate description of electrostatic catalysis in KSI by including orientational effects. As shown in Figure 1B, in addition to developing a bigger C=O dipole moment, ab initio calculations on the isolated, full substrate in the gas phase suggest that the carbonyl bond of the substrate also undergoes a significant angle shift as the reaction proceeds (see SI Methods). Gas-phase optimized structures of the steroid ligand corresponding to the GS, TS, and dienolate intermediate suggest that a C=O dipole reorientation of up to 31° could also be exploited by KSI to maximize the preferential electrostatic interaction with the TS (Figure 1B and 1C). Because geometrical reorientation of the C=O dipole of the TS results mainly from the change in hybridization of the neighboring carbon (C4) from sp3 to sp2, we hypothesized that binding 5α-dihydronandrolone (DHN) and 19NT to KSI could mimic the geometry of the enzyme●substrate complex in the GS and the TS/I states, respectively (Figure 1A lower). We obtained crystal structures of the two inhibitors in complex with WT KSI to assess reorientation of the substrate’s C=O dipole along the reaction coordinate. Furthermore, the electric fields experienced by the C=O of 19NT and DHN when bound to KSI were calculated with MD simulations from the crystallographic coordinates and estimated experimentally with VSE spectroscopy. The difference in the electric fields experienced by the two ligands reflects the extent to which KSI’s electric field is aligned with the TS’s dipole.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Crystal Structures of DHN and 19NT Bound to Wild Type KSI Indicate Distortion of the Ligand Carbonyl Group toward a TS Geometry.

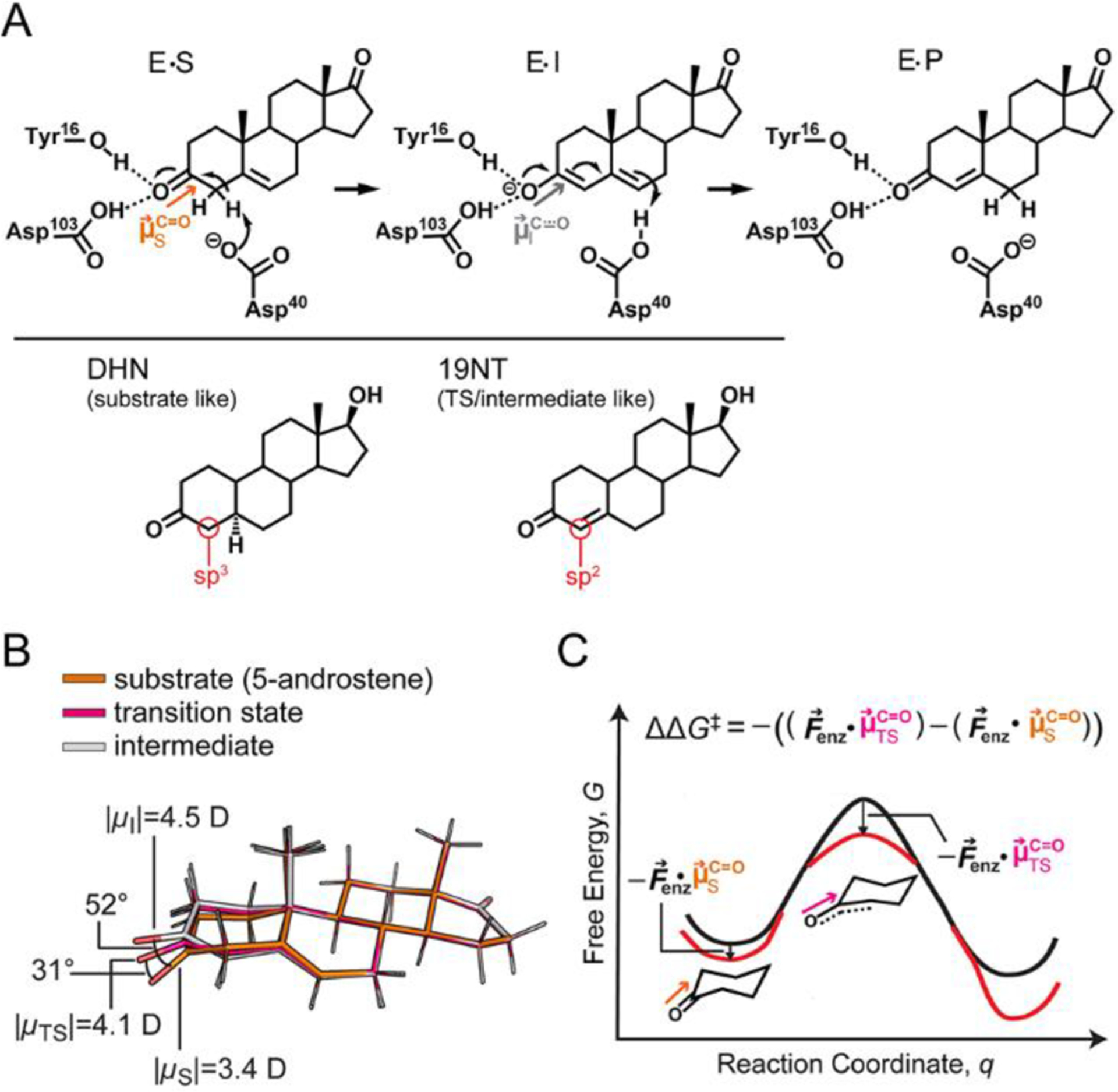

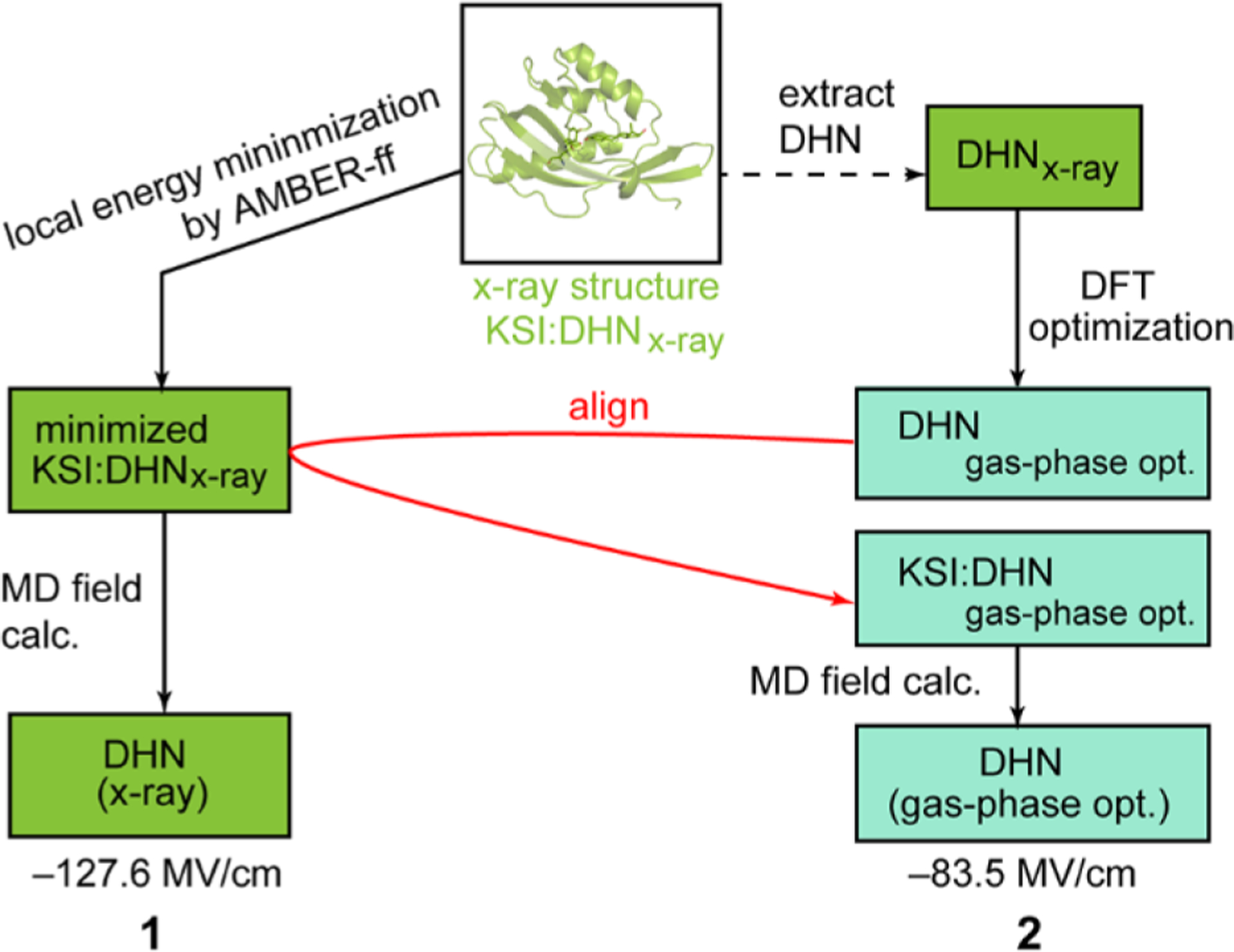

The crystal structures of wild type KSI bound to DHN and bound to 19NT were obtained with a resolution of 1.5 and 1.7 Å, respectively. An overall RMS deviation of 0.177 Å was observed when the two structures are superimposed, suggesting minimal change in the overall enzyme architecture within the error of the structure (Figure 2A and statistics in Table S1). Focusing on the interactions between the ligands and two critical active site residues, Tyr16 and Asp103, the structures show that the positions of the active site residues are virtually unaltered between these two states, while the two ligands (most notably, the C=O bond) assume slightly different orientations relative to the protein. The carbonyl bond of DHN is shifted approximately 14° “down” from that of 19NT, smaller than the predicted difference of 31° from the optimized gas phase geometries (Figure 1B). Importantly, when the ligand geometries taken from the crystal structures are compared with the molecules’ gas-phase optimal geometries, the carbonyl bonds of both ligands are found to be distorted to more closely resemble the TS geometry (Figure 2B and Figure S2), explaining the smaller angle shift in KSI compared to in the gas phase.

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of wild type KSI bound with DHN (6UFS) and with 19NT (5KP4) show perturbed geometry of the ligands. (A) The structure of KSI bound to DHN (green, 1.5 Å) is globally aligned with that of KSI bound to 19NT (blue, 1.7 Å), giving an RMS deviation of 0.177 Å. Within this alignment frame, the angle shift between the carbonyl of DHN and the carbonyl of 19NT is about 14°, smaller than the predicted difference of 31° from the optimized gas-phase geometries (Figure 1B). (B) The C=O bonds of DHN and 19NT get distorted from their gas-phase optimal geometries to more closely resemble the TS structure when bound to KSI. A small energy penalty (ΔE) is calculated from the energy difference between the gas-phase optimal structure of the ligand and the gas-phase structure “constrained” to the crystal coordinates (Figure 3 and Figure S3).

To ensure that the observed geometry distortion is not an artifact from refinement of the structure, we searched the Protein Data Bank for other crystal structures that contain DHN or highly similar molecules as a bound ligand and found two structures: 5α-estran-3,7-dione (ESR) bound to KSID40N from Comamonas testosteroni (an orthologue of the KSI we have studied herein, referred to as tKSI, PDB 1OHP) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) bound to 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (17β-HSD1, PDB 3KLM). We reasoned that if the perturbed geometry of the carbonyl groups in the KSI complexes is functionally relevant, it would be observed in the former structure but not the latter since 17β-HSD1 catalyzes a chemical conversion on the distal D-ring of the steroid and has no activity for the carbonyl group on the A-ring. As shown in Figure S4A, the carbonyl group of ESR bound to tKSI is indeed distorted in a manner highly similar to that of DHN bound to KSI, while the geometry of 17β-HSD1 bound DHT resembles the gas-phase optimized geometry of DHN with mild structural alterations.

These observations are reminiscent of the “Circe effect” proposed by Jencks,12,13 who suggested that enzymes can destabilize a substrate’s reactive region (in this case, the A-ring carbonyl bond) to facilitate its positioning in the enzyme’s active site by utilizing favorable distal interactions (in this case, the multiring system) to offset the former’s free energy cost.12 Using density functional theory (DFT), we estimated that the energy penalty for the bond distortion is close to 1.0 kcal mol−1 by comparing the energy of the gas-phase optimized geometry of the ligands (hereafter denoted as ‘gas phase opt.’) to the gas-phase optimized energy of the ligands but in which the 4 dihedral angles of the A-ring are constrained to their values from the crystal structures (ΔE in Figure 2B). These distortion energies are very likely well below the energetic benefit that could be gained from forming an optimal H-bond or electrostatic interaction between the carbonyl and the oxyanion hole, as will be discussed in the following. Therefore, it is not surprising that KSI’s large active site electric field partially aligns the carbonyl group of the substrate to maximize stabilization of the complex. The resulting TS-like geometry of the ligands thereby provides evidence that the electric field of KSI can orient the C=O to a TS-like geometry and that this geometric preference is imposed upon a substrate-like ligand.

Computational Modeling on the KSI Complex Reveals a High Degree of Alignment between the Carbonyl Dipole of the Bound Ligand and the Electric Field.

To test the hypothesis that the geometric perturbations experienced by steroids in KSI’s active site are utilized for electrostatic catalysis, we carried out simulations using these crystal structures to estimate the electric field KSI projects on the C=O bond dipole in each case and additionally calculated the alignment of the local electric field vector to the C=O bond vector with the equation

| (3) |

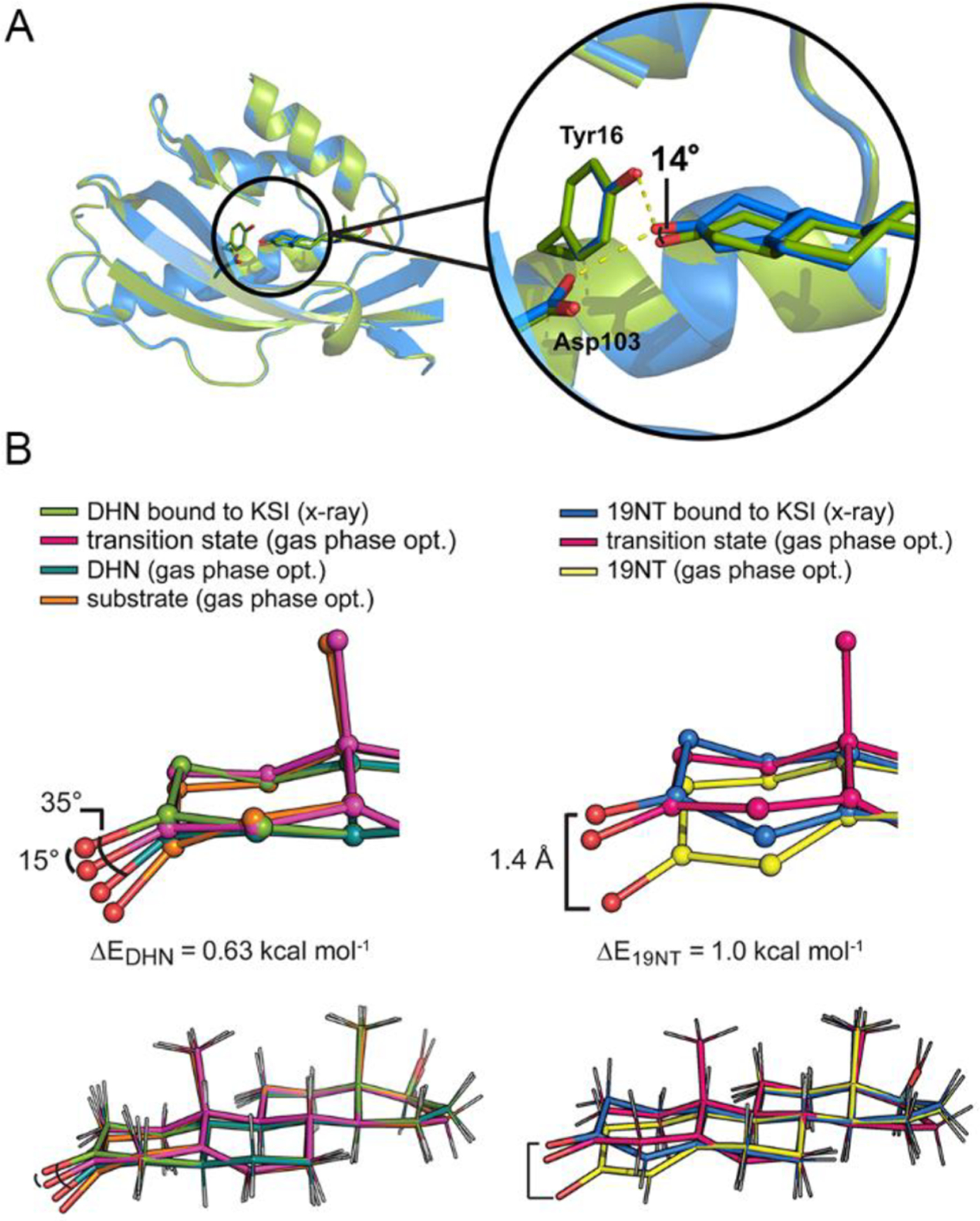

(details in SI Methods) where the numerator corresponds to the projection of the enzyme field onto the C=O bond unit vector, and the denominator is the magnitude of the enzyme field vector.14 The structures of KSI●19NT and KSI●DHN complexes were first energy minimized with the AMBER force field, and then a short simulation was run at low temperature on the energy-minimized complexes to derive the electric field magnitude at the carbonyl of 19NT or DHN and the field’s projection along the C=O vector as previously described (denoted as “X-ray” in Table 1).14 These simulations were intentionally cold and short in order to associate an electric field with the crystallographic configuration and are not intended to reflect a thermally averaged value;15 nevertheless, we ran simulations for ten 1 fs steps to validate the structures were not unstable.15 Next, we removed the DHN (or 19NT) coordinates from the X-ray structures and replaced them with the DFT gas-phase optimized DHN (or 19NT) coordinates by alignment (Figure 3 and also see Figure S3 for the full flowchart explaining these manipulations). These fictitious structures, denoted in Table 1 with the heading ‘gas-phase opt.’ coordinates, enable us to estimate how unfavorable the gas-phase optimal geometries are in the context of the electrostatic interactions created by KSI’s active site.

Table 1.

Calculated Active Site Electric Fields and Their Geometry Relative to the Ligand’s C=O Bond Vectora

| coordinatesa | DHN (Substrate like) | 19NT (TS like) | TS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray (1) | gas phase opt. (2) | X-ray (6) | gas phase opt. (7) | gas phase opt. (5) | |

| Field magnitudeb (MV/cm) | −139.5 | −105.3 | −160.4 | −100.9 | −151.8 |

| Feld projectionc (MV/cm) | −127.6 | −83.5 | −141.7 | −76.1 | −144.6 |

| %alignedd | 91% | 79% | 88% | 75% | 95% |

| Δstabilizatione (kcal mol−1) | 6.6 | reference | 10.7 | reference | / |

| C=O…O16 (Å) | 2.53 | / | 2.57 | / | 2.70 |

| C=O…O103 (Å) | 2.76 | / | 2.65 | / | 2.48 |

See Table S2 and Figure S3 for complete simulation scheme and results. The number of each entry corresponds to the respective species in Figure 3 and Figure S3.

The electric field magnitude, , is the average of the magnitude of the enzyme’s electric field at the C and O atoms of the bound ligand.

The electric field projected on the carbonyl is calculated by , and also equals · %aligned, where is the magnitude of the enzyme’s field.

The %aligned is calculated by eq 3.

Δstabilization (the stabilization energy gained from C=O distortion) is the difference of the field projection multiplied by the dipole of the carbonyl (1 MV cm−1 D ≃ 0.048 kcal mol−1).

Figure 3.

Modeling scheme of different KSI●DHN structures for MD calculations. Each pose is given a number whose corresponding simulation results are listed in Table 1 and Table S2. (See Figure S3 for a more detailed scheme including all calculations).

As shown in Table 1, by dividing the projected field with the electric field magnitude (eq 3), we found that KSI’s electric field is approximately 90% aligned with the carbonyl dipole of both DHN and 19NT. The %aligned further increases to 95% when the modeled TS structure is docked into KSI by aligning it to 19NT (Figure 3 and Figure S3). Focusing on how the electric field is experienced by the carbonyl bond itself, the field projection on 19NT’s carbonyl bond (−141.7 MV/cm) agrees well with that measured by VSE spectroscopy (−141.3 MV/cm, Table S3),1 as well as with high-level quantum simulations (−152 MV/cm),16 highlighting the principal role of electrostatics in explaining this interaction. The value is also close to the predicted field on the TS’s C−O bond (−144.6 MV/cm), demonstrating 19NT to be a faithful probe for KSI’s electrostatic environment in the TS because KSI perturbs 19NT’s geometry to become very TS-like (Figure 2B and Figure S2). The field projection on DHN’s carbonyl bond is 14 MV/cm smaller than that of 19NT (−127.6 MV/cm), which can be explained in part because the O−O distance between the carbonyl of DHN and the hydroxyl group of Asp103 is slightly longer (~0.1 Å) than its counterpart in the 19NT complex.16 We note that since these calculated electric fields reflect X-ray structures, they do not represent ensemble-averaged electric fields. Nevertheless, their consistency with a population from MD simulations (ref 15) and experimental rate constants (Discussion S1) suggest that they represent ground state conformations that are most likely the catalytically relevant states.15

As seen in Table 1, the electric fields calculated based on the ligands’ actual geometries when bound to KSI are considerably larger than those based on the gas-phase optimized geometries (also see Table S2 and Discussion S1). These calculations, though based on fictitious structures, suggest a significant energetic benefit associated with bringing the C=O dipole deep in the active site and aligned with KSI’s electric field. We estimate these structural rearrangements strengthen the enzyme’s electrostatic interaction with DHN by ~6 kcal mol−1 and with 19NT by ~11 kcal mol−1 – more than enough to compensate for the small energetic cost of ~1 kcal mol−1 from local ligand bond distortion. These results imply that despite what may superficially appear to be a distortion from inspection of the structure, KSI’s binding mode of its substrate in fact stabilizes the C=O dipole in both the GS and TS structures, in contradistinction to the Circe effect (Figure S5).

Large, Preoriented Electrostatic Environment in KSI Provides Its Catalytic Power over Simple Solvent.

The calculations above using crystallographic structures point to an electrostatic environment in KSI’s active site that is preorganized toward the TS geometry. Upon binding to KSI, the substrate-like ligand is driven by a large, oriented electric field to assume a TS-like geometry at the reactive site, so that minimal dipole reorientation needs to occur during the reactive event.

Using the projected fields on the carbonyl of 19NT and DHN (Table 1), we can estimate the partial contribution of the orientational effect to electrostatic catalysis by KSI, described at the outset. The total electrostatic contribution to the barrier reduction estimated using eq 1 is

noting that 1 MV cm−1 D is approximately 0.048 kcal mol−1. In contrast, the stabilization energy if only the scaling effect was considered estimated using eq 2 is

The angular preference of the active site electric field favoring the TS geometry therefore imparts an additional stabilization energy of 2.3 kcal mol−1, corresponding to 30% of the total electrostatic contribution to the barrier reduction. On the basis of this simple analysis, KSI is able to selectively stabilize the TS significantly more than the GS by exploiting a fairly small shift in C=O orientation. This notion of “geometric discrimination” has been previously discussed,20 although it is treated here quantitatively within an electrostatic framework. In this context, we might refer to the active site electric field as “preorganized” because it (i) optimally stabilizes the TS geometry and (ii) does not change to accommodate the GS geometry (as a bulk solvent would), but rather forces the GS to assume a more “TS-like” geometry. Note that, the catalytic effect ascribed to electrostatics here is quite similar to the value we estimated previously (7.3 ± 0.4 kcal mol−1)6, though importantly, here, we have obtained the result without any extrapolations (also see Discussion S2).17

The preorganization of the electric field in enzymes highlights its fundamental difference from the solvent reaction field in aqueous solutions, which is instead optimized for the GS charge distribution and has to reorient to accommodate the TS as the reaction proceeds, imposing a reorganization energy.4 The energetic cost of solvent reorganization limits the catalytic capacity of water despite the significant magnitude of its electric field (Figure S5).4,18

We sought to further validate this notion experimentally by measuring the electric field projection on the carbonyl of DHN via VSE spectroscopy, under which conditions the enzyme-ligand interaction is fully equilibrated. In order to obtain reliable IR spectra of the carbonyl group in the midst of the strong background from the protein amide band I, it is essential to obtain isotope-edited difference spectra, as was done for 19NT previously.1 While it is straightforward to prepare the 18O-substituted version of DHN, rapid back-exchange with bulk water, even when the sample was prepared in D218O (and the protein uniformly 13C labeled to shift the amide I band), made it difficult to obtain definitive data (in contrast, back-exchange for 19NT is very slow). The results of our attempts to perform these measurements are presented in Discussion S3 and Figure S6.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this work clarifies a number of important aspects about electrostatic catalysis. Perturbed substrate geometry has long been considered a key factor in promoting catalysis;19–21 however, the belief that such distortions implied a ground-state destabilization contribution could not be easily reconciled with computation and theory.22 Here, we show that the catalytic effects associated with altered substrate geometry are best interpreted within an electrostatic framework, where they serve to prime a substrate for movement to a transition state, which can nevertheless be stabilizing in the ground state thanks to large active site electric fields. In KSI, this orientational effect provides a significant catalytic contribution, which is impressive in that the geometric changes during this reaction are actually quite small. The benefits of a preorganized electrostatic environment would be expected to be even more profound in cases where a substrate’s geometrical reorientation along the reaction coordinate are more dramatic, as is the case in many other enzymatic transformations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by NIH Grant GMR35-118044 (to S.G.B.). Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393). S.D.F. was supported by a Junior Research Fellowship from King’s College, Cambridge (UK) at the time of this work. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.0c00383.

Experimental procedures, crystallographic data, complete information on the computational modeling scheme and results, raw IR spectra of DHN, and further evaluation on the energy profile of the isomerization reaction in KSI and in solution (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Fried SD; Bagchi S; Boxer SG Extreme electric fields power catalysis in the active site of ketosteroid isomerase. Science 2014, 346, 1510–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wu Y; Boxer SG A critical test of the electrostatic contribution to catalysis with noncanonical amino acids in ketosteroid isomerase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 11890–11895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Radzicka A; Wolfenden R A proficient enzyme. Science 1995, 267, 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Warshel A; Sharma PK; Kato M; Xiang Y; Liu H; Olsson MHM Electrostatic basis for enzyme catalysis. Chem. Rev 2006, 106, 3210–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hanoian P; Liu CT; Hammes-Schiffer S; Benkovic S Perspectives on electrostatics and conformational motions in enzyme catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 482–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Fried SD; Boxer SG Measuring electric fields and noncovalent interactions using the vibrational Stark effect. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2017, 86, 387–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zoi I; Antoniou D; Schwartz SD Electric fields and fast protein dynamics in enzymes. J. Rhys. Chem. Lett 2017, 8, 6165–6170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Herschlag D; Natarajan A Fundamental challenges in mechanistic enzymology: progress toward understanding the rate enhancements of enzymes. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 2050–2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Menger FM; Nome F Interaction vs. preorganization in enzyme catalysis. A dispute that calls for resolution. ACS Chem. Biol 2019, 14, 1386–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Pollack RM Enzymatic mechanisms for catalysis of enolization: ketosteroid isomerase. Bioorg. Chem 2004, 32, 341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Fafarman AT; Sigala PA; Schwans JP; Fenn TD; Herschlag D; Boxer SG Quantitative, directional measurement of electric field heterogeneity in the active site of ketosteroid isomerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A 2012, 109, E299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Jencks WP Binding energy, specificity, and enzymic catalysis: the circe effect. Anvances Enzymol. Relat. Sub 2006, 43, 219–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Page MI; Jencks WP Entropic contribution to rate accelerations in enzymic and intramolecular reactions and the chelate effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1971, 68, 1678–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Fried SD; Bagchi S; Boxer SG Measuring electrostatic fields in both hydrogen-bonding and non-hydrogen-bonding environments using carbonyl vibrational probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 11181–11192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Welborn VV; Head-gordon T Fluctuations of electric fields in the active site of the enzyme ketosteroid isomerase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 12487–12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wang L; Fried SD; Markland TE Proton network flexibility enables robustness and large electric fields in the ketosteroid isomerase active site. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 9807–9815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Natarajan A; Yabukarski F; Lamba V; Schwans JP; Sunden F; Herschlag D Comment on “Extreme electric fields power catalysis in the active site of ketosteroid isomerase. Science 2015, 349, 936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Fried SD; Boxer SG Response to comments on “Extreme electric fields power catalysis in the active site of ketosteroid isomerase”. Science 2015, 349, 936–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Blake CC; Johnson LN; Mair GA; North AC; Phillips DC; Sarma VR Crystallographic studies of the activity of hen egg-white lysozyme. Proc. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci 1967, 167, 378–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Robertus JD; Kraut J; Alden RA; Birktoft JJ Subtilisin: a stereochemical mechanism involving transition-state stabilization. Biochemistry 1972, 11, 4293–4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Fastrez J; Fersht AR Demonstration of the acyl-enzyme mechanism for the hydrolysis of peptides and anilides by chymotrypsin. Biochemistry 1973, 12, 2025–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Warshel A Electrostatic origin of the catalytic power of enzymes and the role of preorganized active sites. J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273, 27035–27038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.