Abstract

In light of growing scholarly works on business failure, across the social science domains, it is surprising that past studies have largely overlooked how extreme environmental shocks and ‘black swan’ events such as those caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and other global crises, can precipitate business failures. Drawing insights from the current literature on business failure and the unfolding event of COVID-19, we highlight the paradoxes posed by novel exogenous shocks (that is, shocks that transcend past experiences) and the implications for SMEs. The pandemic has accelerated the reconfiguration of the relationship between states and markets, increasing the divide between those with political connections and those without, and it may pose new legitimacy challenges for some players even as others seem less concerned by such matters, whilst experiential knowledge resources may be both an advantage and a burden.

Keywords: Business failure, Paradox organizational failure, Closure, Exit, COVID-19, Novel global crisis

1. Introduction

Prior to the 21st century, many of the challenges facing global businesses revolved around how to mitigate business failure (see Amankwah-Amoah & Syllias, 2020). However, in discussing both business ailments and remedies, a great deal of the literature rested on two fundamental assumptions: the increasing primacy of markets, and that much could be taken for granted about the global business ecosystem. Although the latter was not immune to periodic unexpected downturns, challenges took familiar forms (e.g. recessions), and a limited range of policy remedies, centering on generous central bank interventions to support and sustain borrowing and relieve debt, seemed capable of restoring growth. Recent developments, including the rise of right-wing populism in mature liberal markets, climate change, and, most recently, the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic have challenged these assumptions. Although climate change may have greater long-term consequences, the COVID-19 pandemic has had more immediate effects on the global business ecosystem. Accompanying the COVID-19 pandemic, with more than 14 million cases and over 600,000 fatalities globally affecting countries across Africa, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, Europe, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific (World Health Organization, 2020; Worldometers, 2020), are multiple cases of foreclosures, massive unemployment, car repossessions, and waves of business failures ranging from retailers, airlines, and health, fitness, & wellbeing centers, among several others. In the UK, for instance, the pandemic has exponentially led to an increase in the number of financially distressed companies. It is estimated that around “half a million firms are at risk of collapse” (Cook & Barrett, 2020, p. nd). This has caused widespread economic distress, with a likely long-term impact on the global economy.

According to a report by the International Civil Aviation Organization (2020), COVID-19 could lead to reductions of up to 71% of seat capacity and around 1.5 billion passengers globally by the end of 2020, exemplifying the precarious nature and effects of the pandemic on airline businesses and the financial position of multiple firms that provide support services to airlines and airports. These demonstrate a looming problem facing industry and public policy and the need for better understanding of the conditions leading to business failure and how best to mitigate them. As recently observed by Walsh (2020, p. nd), “companies large and small are succumbing to the effects of the coronavirus”, and 2020 has been projected to “set a record for so-called mega bankruptcies”. Yet, we lack a systematic understanding of how the pandemic can create conditions leading to business failure. As many small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and multinational enterprises (MNEs) teeter on the edge of closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a need for deeper understanding of processes leading to business failure.

There is a growing body of research on business failure (see Amankwah-Amoah & Syllias, 2020; Boso, Adeleye, Donbesuur, & Gyensare, 2019; Habersang, Küberling-Jost, Reihlen, & Seckler, 2019; Kücher, Mayr, Mitter, Duller, & Feldbauer-Durstmüller, 2020; Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2004; Rider & Negro, 2015; Shepherd, 2003). However, as we have seen, past “shocks” of this nature have involved comfortingly familiar phenomena, making it challenging to theorize about challenges outside the realm of past experience (Wood, 2019); the last global pandemic, Spanish flu, occurred a century ago, when the global economy was in a very different place. Hence, although organizations can arguably learn from others’ failures rather than their successes (Desai, 2011), there is a lack of experience in dealing with failure brought about by novel events. Against this backdrop, the key purpose of this work is to highlight how misfits and misalignments can, over time, generate “knock-on effects” under such circumstances, and what this might tell us about challenges that transcend the resources of past experience.

In addressing the deficit in our understanding in the light of COVID-19, the study makes key contributions to the literature. First, although COVID-19 remains a disruptive force with long-term implications for global and local businesses (see Wenzel, Stanske, & Lieberman, 2020), scholars are yet to articulate how it shapes the processes leading to business failures. In this direction, the study moves beyond the widely held view that business failure is attributable to either the deterministic perspective (environmental factors) or voluntaristic (firm-specific factors) perspectives (Amankwah-Amoah, 2016; Kücher et al., 2020; Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2004), through highlighting the fundamental differences between genuinely novel shocks and shocks for which there is a base of relevant experiential knowledge regarding the challenges they pose, and the new set of paradoxes this leads to. The remainder of the article is organized along the following lines: After presenting an overview of key strands of relevant literature on exogenous shocks and business failure, we set out the background to the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects in triggering business failures. The final section sets out the implications of the analysis for business failure research and practicing managers.

2. Business failure: a review

For analytical clarity, business failure refers to a situation where the business is no longer able to operate as a sustainable entity and is thus forced to cease operations and lay off any employees (Fleisher & Wright, 2010; Sheppard, 1994). This not only prompts the retreat and exit from domestic markets, but also foreign ones. There are different types of business failure—one which is largely sudden, unpredictable, and difficult to mitigate, and the other which is largely protracted and punctuated by multiple events, stories, false starts, and actions which ultimately lead to failure (D’Aveni, 1989b, 1989a; Hamilton, 2006). Thus, business failure is taken to mean the gradual or sudden death of a business.

Much of the literature tends to mention the challenges of coping with events. Broadly speaking, scholars have tended to adopt either the deterministic or voluntaristic perspectives to account for business failure (Heracleous & Werres, 2016; Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2004, 2010). The deterministic (environmental factors) perspective attributes business failure to uncontrollable or external factors over which managers have little or no control (see also Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2004). Rooted in the deterministic perspective is the focus on the general and industry environment conditions that may exacerbate business failures. Prior research in this area has typically considered business failure to be an outcome of the process of “natural selection” and “survival of the fittest” (Andrews, Boyne, & Enticott, 2006). One of the common threads in these studies is their emphasis on how factors such as liberalization, declining customer demand, and intense competition can trigger the process of business decline, leading to failure (Amankwah-Amoah, 2016). Early studies of business failure often explored general environmental factors such as technological changes, recession, general environmental volatility, new government taxes, and deregulation as primary causes of business failure (see Silverman, Nickerson, & Freeman, 1997). Yet, as we have seen, this literature focuses on recurrent external challenges, that any business operating in a particular setting might have to cope with from time to time (cf. Micelotta, Lounsbury, & Greenwood, 2017).

A distinct stream of research entrenched in the voluntaristic perspectives suggests that bundles of firm attributes such as leadership, management, resources and capabilities, and firm age are the root causes of business failure (Kücher et al., 2020; Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2004). By emphasizing the influence of resources and capabilities in determining the life chances of organizations, this stream of research has attempted to counterbalance the overwhelming emphasis on external factors as primary causes of business failure. For instance, the liability of smallness’ perspective of business failure (Freeman, Carroll, & Hannan, 1983) contends that business failure rates decline as the firm expands its scope of operations, for example, through internationalization. Accompanying firm expansion may be resource accumulation. There may also be gains through the increased geographical scope and scale that comes if the firm internationalizes, thereby spreading the risk of the business. Consequently, these gains buffer firms against sudden changes in their external environment and threats either at home or internationally (see also Baum, 1996). From this perspective, the essential difference between these competing views is the unit of analysis in examining causes of business failure. Many recent scholarly contributions have highlighted the interaction of firm-level and external factors as a potentially robust explanation for business failure (Amankwah-Amoah, 2016). Backing up the “commonsense” view that it is likely to be a combination of the two, there is a great deal of work that confirms a mix of external and internal factors (Dahlin, Chuang, & Roulet, 2018). Yet, a limitation remains that, in the realm of factors identified that might possibly cause failure, there is focus on those where past experience might aid present coping (c.f. Wood, 2019).

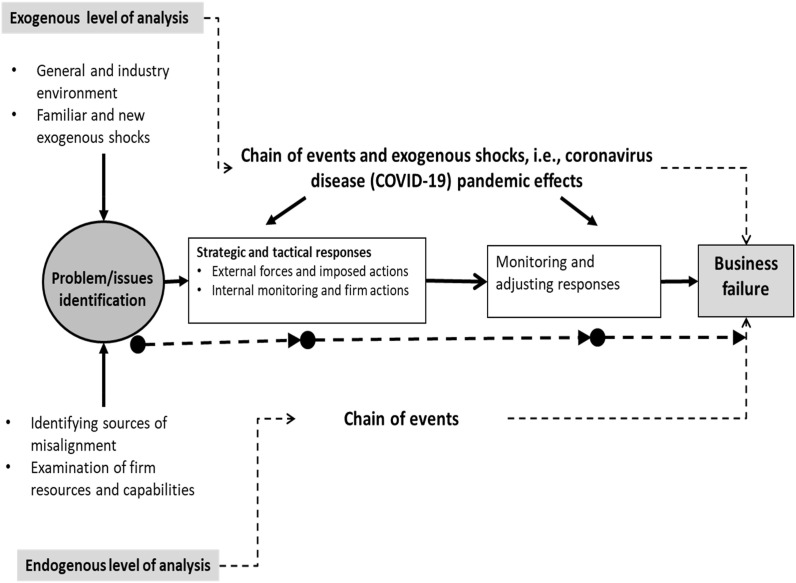

Business failure may stem from the mismatch between the organization and its business environment (Drazin & Van de Ven, 1985; Sabherwal, Hirschheim, & Goles, 2001), that is internal and external misfits. Internal misfit stems from mismatch between the firm’s resources, structure, practices, and strategy, whereas external misfit refers to the mismatch between the firm-specific factors, and the home, host, or global environment (see Gammeltoft, Filatotchev, & Hobdari, 2012). This suggests that, over time, a chain of events can turn a firm’s competitive advantage into liabilities and a source of errors and failure. As Thompson (1967, p. 234) recognized decades ago, alignment is “a moving target”. This requires continuous upgrading and updating of resources and capabilities in a timely manner to avert environmental shift, rendering the current strategy obsolete. We now turn our attention to Fig. 1 as our organizing framework.

Fig. 1.

A general model of processes leading to business failures.

3. The global business environment and COVID-19: An overview

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020), the COVID-19 pandemic is regarded as one of the largest concurrent public health and economic crises in modern times, culminating in sharp decline in consumption and consumer confidence. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic has been recognized as a major exogenous shock that has altered the competitive landscape for both small and large firms (Wenzel et al., 2020). In many instances, it has led to a collapse in demand, and disruption of supply of many products. In respond to the crisis, governments around the globe have embraced border closures, instituted social distancing measures, and issued directives and guidelines to small and large businesses. For instance, according to Opinium Research (2020), around 7% per cent of SMEs in UK have already permanently closed down due to the COVID-19 pandemic and many are teetering on the verge of closure and collapse. Besides the closures, many firms have introduced several mitigating measures such as remote working, reduced hours, furlough schemes, closed offices, and redundancies (Opinium Research, 2020). These events have posed particularly severe challenges in specific sectors, leading to the rapid decline and eventual exit of different types of firms including small and large businesses.

Following the implementations of social distancing and lockdown measures imposed by governments, the global airline industry was heavily affected. Indeed, the effects of the pandemic have manifested in mass layoffs, adoption of new costly processes, and bankruptcies/closures (Amankwah-Amoah, 2020). The fall in passengers’ demand drained the financial resources and cash reserves of many airlines, leading to the collapse of some. Indeed, the travel and quarantine restrictions imposed by countries brought falling demand for air travel and international travel to a virtual standstill in early 2020 (Dunn, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated the collapse of struggling UK-based carrier Flybe in March 2020 (Salaudeen, 2020), and Trans States Airlines collapsed (Wolfsteller, 2020). The pandemic also contributed to the bankruptcy of Miami Air International, which demonstrates the high economic cost of this global health crisis.

Around the world, many SMEs in 2020 have faced increased exposure stemming from the ongoing epidemic outbreak. According to the European Investment Bank (2020), the pandemic has created a demand and supply shock leading to such businesses being unable to raise revenue and pay rent. Indeed, SMEs are the backbone of the European economy, accounting for around two-thirds of overall employment and over 55% of the value added in the non-financial business sector (European Investment Bank, 2020). This is partly due to the containment measures introduced by governments around Europe and beyond that placed a limit on travel and thus halted or curtailed demand in several sectors such as air transport, tourism, and automotive, and of course the direct effects of the pandemic (see Dunn, 2020). The sudden “environmental shock” triggered by COVID-19 has exponentially depleted firms’ financial resources and increased insolvencies, creating financial distress in organizations and weakening the financial position of many large and small businesses, and thereby forcing many to seek government support in the form of subsidies, tax relief, and other financial and non-financial support (Cook & Barrett, 2020). To a large extent, many sectors have been forced to “compete on sanitation” in marking their premises and settings to minimize potential for viral transmission.

Many of these effects have been made much worse by excessive corporate debt. Although according to classical agency theory, corporate borrowing keeps management on a tight rein, forcing them to concentrate on returns rather than empire building (Jensen, 1986), it has been evident that proliferating debt is ultimately unsustainable. This is especially so given that a focus on borrowing and distribution may distract managers from orthodox economic activities centered on the generation and sale of goods and/or services, resulting in core business capabilities withering away. In addition, borrowing models are centered on assumptions that the future business environment would be sufficiently predictable to enable continued debt servicing. The pandemic has highlighted both the fallacy of the latter assumption and the excessive nature of corporate borrowing. Whilst in the UK and the US governments were quick to institute measures to relieve corporate debt, the focus was on politically influential sectors and insider corporations with close links to politicians. This process has left those SMEs without close ties to individual politicians in a difficult place. Again, promised help to small business proved partial, selective, and seemingly insufficient, especially when compared to the help lavished elsewhere. What the bailouts highlighted was the increasing reliance of markets on the state to sustain; even if temporary, this revealed the limitations of assumptions that markets would trump government, and the triumph of non-market strategies. Hence, this showed that managerial assumptions about predictable futures may be rendered irrelevant by events that transcend past experience.

4. Organization-environment fit

Having set out the background of business failure, we now move on to examine the organization-environment fit/misfit shape by exogenous shock leading to business failure.

4.1. Institutional misfit

Existing work highlights the challenges posed by misalignments between firms and institutions (Gammeltoft et al., 20120). Such misalignments can manifest due to incompatibilities of the business processes, decisions, and routines with external requirements such as government standards, regulations, and directives. Often, such misalignments stem from assumptions regarding long regulatory continuity and/or predictions that future government policies would tend towards ever lighter regulation. Stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic have been government directives to close borders, and new directives to hospitality, airline, and other industries aimed at curtailing movement of people. It has also led to government interventions in the global trade of healthcare supplies and new tariffs to protect national strategic industries. Although the COVID-19 pandemic is threatening many SMEs, they often lack the capacity to quickly change their business model to embrace new routines and processes. The financial pressures and strains on business models accompanying practicing social distancing and adhering to governments’ new directives make failure more likely. In summary, predictions as to the future drift of government policies (e.g. liberalization) have proven incorrect. Yet, whilst there has been much greater government regulation, it has been uneven, poorly coordinated internationally (leading to competing demands on MNEs), and, in the case of a number of major economies, ranging from the US to Brazil, chaotic. Accordingly, this would challenge memory-informed firm strategic choices.

Traditionally, it has been held that misalignment with local institutional demands or multiplicity of the real-world local contexts of the organization can undermine its source of legitimacy (Lejano & Shankar, 2013). A firm’s environment imposes pressures on it to modify its behavior, processes, methods of operations, and systems to achieve institutional fit. Firms in industries such as aviation benefited from government support, privileged access to resources, and, in many instances, subsidies. By adhering to local institutional demands, organizations enhance their legitimacy claims as well as improve access to local expertise and resources (Volberda, van der Weerdt, Verwaal, Stienstra, & Verdu, 2012). The behavior of some of the tech giants, and, at the very least, sections of the oil and gas industry might suggest that at least some players are sufficiently confident in their oligopolistic market status and/or political clout to be able to be apparently less than troubled by legitimacy concerns. Those who lack such a market and/or political status (e.g. SMEs) would be under much greater pressure to demonstrate legitimacy in the face of institutional misalignment.

4.2. Strategic misalignment

Strategic misalignment occurs when the firm is unable to initiate change and upgrade and update its resources to respond to external environmental factors in a timely manner. Misaligned processes deviate from the requirements of the business environment at the time. This may stem from the inability to keep pace with technological breakthroughs and competitors’ actions and moves. Although strategic alignment can lead to developing sustainable competitive advantage, inability to maintain the alignment can become a liability putting the firm “on the road to disaster” (Heracleous & Werres, 2016). Indeed, scholars have hinted that strategic misalignment can lead to failure (Miller, 1996; Sheppard, 1994). As Thornhill and Amit (2003) asserted, business failure is more likely to occur when there is misalignment between the capabilities and resources of the firm and the environmental demands. Routines are identifiable patterns of activity embodied in how the firm interacts with internal and external parties/stakeholders (Mitchell & Shaver, 2002; Nelson & Winter 1982). Old routines are often very difficult to change due to their deeply entrenched nature within the organization.

Resource misfit refers to the mismatch between the existing resources and the resources and expertise required to neutralize or deal with the environmental threat. This suggests that the processes inherent in assembling, marshalling, and utilizing resources can be faulty, leading not only to misallocation of the resources but also to exposing its vulnerabilities in the wake of new competitive threats. Indeed, business failure is argued to stem from misalignment between the unique resources and capabilities of the organization and the demands of the new business environment such as the COVID-19 pandemic (see also Thornhill & Amit, 2003). The inefficient resource deployment and utilization can create conditions for business failure to occur. In addition, underestimation or overestimation of threats can lead to inappropriate action being taken, leading to misallocation of resources or resource misalignment. Table 1 highlights different dimensions of business failure research and some of the key research questions.

Table 1.

Dimensions of business failure research and new research questions.

| Dimensions | Key insights | New research questions/agenda |

|---|---|---|

| Deterministic (environmental factors) perspective encompasses theories such as institution-based view and the industrial organization. |

|

|

| Voluntaristic (firm-specific) perspective encompasses theories such as dynamic capabilities, routine-based perspectives, and organizational ecology. |

|

|

| An integrated perspective (internal-external interface) |

|

|

5. Discussion and implications

Although business failure is more prevalent in the 21st century, the expanding body of research is yet to translate into an improved understanding of how novel shocks (i.e. exogenous shocks which transcend past experience and knowledge) such as the COVID-19 pandemic might precipitate business failure. In this direction, our analysis also underscores the point of alignment between firm-level resources and capabilities and the external environment that transcends past experience as sources of external misfits. More specifically, although a great deal has been written about exogenous shocks (Micelotta at al., 2017), most of the existing literature focuses on those whose form assumes familiar shapes (Wood, 2019). Yet, currently, there are a number of high probability novel shocks: this would not only include the present pandemic, but future ones of different causes and scopes (e.g. antibiotic resistant bacterial ones) and those posed by climate change as well as by unprecedented political instability in large developed countries such as the US. It might be argued that none of these developments are novel, in that there have been innumerable attempts to raise awareness about their high probability and the risks they bring with them. Yet, because their occurrence transcends the past body of recent experience and because dealing with them will require fundamental economic, political, and environmental changes.

SMEs differ from their larger counterparts in that their more limited range of scale and scope – and human resources – would limit the range of organization-specific experiential knowledge. This paper highlights how this may place them at a disadvantage when compared to their larger counterparts. However, paradoxically, this may also confer real advantages. A large repository of experiential knowledge may lead to strategy informed by comfort, involving a regression to trusted past remedies; those organizations that are experientially lighter may be better equipped to deal with novel shocks. Yet, the paradox posed by knowledge resources and experience may be rendered less important by other paradoxes. Although the 1990s and early 2000s were seen as an age of market supremacy, this period saw a gradual move towards non-market strategies by large players in the liberal markets (Wood & Wright, 2015). Again, pressures towards greater competitiveness were offset by the rise of oligopolies in growing areas of the economy, such as internet technology, and a reliance on debt, rather than genuine competitiveness in the generation and sale of goods and services to secure shareholder value (Lazonick & Shin, 2019). In addition, all these would favor larger players and those with richer political ties, over smaller and emerging players. Indeed, even SME-orientated bailouts in the US and the UK have favored insider and some surprisingly large players. Although regulatory shifts to cope with the pandemic have worsened institutional misalignment, it is larger players that are in a much stronger position to remake rules to their own liking (McDermott, 2019). Moreover, whilst institutional misalignment is commonly seen as driving legitimacy-seeking behavior by firms (Desai, 2011), a contemporary phenomenon has been of large players in specific sectors seemingly becoming less troubled by legitimacy concerns. The latter may have a ripple effect across an economy, as others mimic such behavior; yet, organizations with more limited resources may become even more dependent on those that legitimacy might confer.

Theoretically, we extend the discourse around the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on businesses (Amankwah-Amoah, 2020; Pereira, Temouri, Patnaik, & Mellahi, 2020) by extending and providing insights on the paradoxes generated by novel shocks around knowledge resources, strategy, and legitimacy. From a practical standpoint, it is worth noting that the risk of business failures is likely to increase given the uneven and capricious nature of government bailouts in many mature and emerging markets; quite simply, there is no rulebook or set of best practices for guiding policy interventions. To bridge the alignment gaps, it is well known that renewing and upgrading a firm’s resources in a new environment is essential for ensuring its long-term success (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). More challenging is understanding the basis of such a renewal, given the high likelihood of further novel shocks, and the rapidly shifting boundaries between state and market.

In addition to questions posed in Table 1, several promising avenues for future research are apparent. First, a promising avenue would be to explore why firms strive to learn from the COVID-19 pandemic and firm failures linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. It might also be interesting to explore the effects of national and organizational cultures in learning from pandemic-related policy and firm failures. Furthermore, although scholars have recognized failure to be an integral feature of entrepreneurship (Aldrich & Martinez, 2001; Baù, Sieger, Eddleston, & Chirico, 2016; Shepherd, 2003), much of the existing research overlooks the continuous effects of business failure beyond the focal firm. Often, small business owners leaving industries as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic go unnoticed, but this presents promising avenues to explore how these entrepreneurs re-emerge with new firms. In addition, future studies could explore how firms adapt and scale up their business models when faced with extreme external shocks. It is our hope that our analysis would help in revitalizing interest in business failures in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- Aldrich H.E., Martinez M.A. Many are called, but few are chosen: An evolutionary perspective for the study of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice. 2001;25(4):41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah J. An integrative process model of organisational failure. Journal of Business Research. 2016;69:3388–3397. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah J. Stepping up and stepping out of COVID-19: New challenges for environmental sustainability policies in the global airline industry. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah J., Antwi-Agyei I., Zhang H. Integrating the dark side of competition into explanations of business failures: Evidence from a developing economy. European Management Review. 2018;15(1):97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah J., Boso N., Antwi-Agyei I. The effects of business failure experience on successive entrepreneurial engagements: An evolutionary phase model. Group & Organization Management. 2018;43(4):648–682. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah J., Wang X. Business failures around the world: Emerging trends and new research agenda. Journal of Business Research. 2019;98:367–369. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah J., Wang X. Opening editorial: Contemporary business risks: An overview and new research agenda. Journal of Business Research. 2019;97:208–211. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah J., Syllias J. Can adopting ambitious environmental sustainability initiatives lead to business failures? An analytical framework. Business Strategy and the Environment. 2020;29(1):240–249. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews R., Boyne G.A., Enticott G. Performance failure in the public sector. Public Management Review. 2006;8:273–296. [Google Scholar]

- Baum J.A.C. In: Handbook of organization studies: 77-114. Clegg S.R., Hardy C., Walter N., editors. Sage; London: 1996. Organizational ecology. [Google Scholar]

- Baù M., Sieger P., Eddleston K.A., Chirico F. Fail but try again? The effects of age, gender, and multiple-owner experience on failed entrepreneurs’ reentry. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Boso N., Adeleye I., Donbesuur F., Gyensare M. Do entrepreneurs always benefit from business failure experience? Journal of Business Research. 2019;98:370–379. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley S., Aldrich H., Shepherd D.A., Wiklund J. Resources, environmental change, and survival: Asymmetric paths of young independent and subsidiary organizations. Strategic Management Journal. 2011;32:486–509. [Google Scholar]

- Cook L., Barrett C. How Covid-19 is escalating problem debt. 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/4062105a-afaf-4b28-bde6-ba71d5767ec0 Received 3-6-2020, from.

- D’Aveni R.A. The aftermath of organizational decline: A longitudinal study of the strategic and managerial characteristics of declining firms. Academy of Management Journal. 1989;32:577–605. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aveni R.A. Dependability and organizational bankruptcy: An application of agency and prospect theory. Management Science. 1989;35:1120–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin K.B., Chuang Y.T., Roulet T.J. Opportunity, motivation, and ability to learn from failures and errors: Review, synthesis, and ways to move forward. Academy of Management Annals. 2018;12:252–277. [Google Scholar]

- Desai V. Mass media and massive failures: Determining organizational efforts to defend the field’s legitimacy following crises. Academy of Management Journal. 2011;54:263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Drazin R., Van de Ven A.H. Alternative forms of fit in contingency theory. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1985;30(4):514–539. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G. The story of the coronavirus impact on airlines in numbers. 2020. https://www.flightglobal.com/strategy/how-the-airline-industry-has-been-hit-by-the-crisis/138554.article Retrieved 06.05.2020, from.

- Eisenhardt K.M., Martin J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal. 2000;21(10/11):1105–1121. [Google Scholar]

- European Investment Bank Does this change everything? Small business gets sick. 2020. https://www.eib.org/en/stories/smes-coronavirus Retrieved 06.05.2020, from.

- Fleisher C.S., Wright S. Competitive intelligence analysis failure: Diagnosing individual level causes and implementing organisational level remedies. Journal of Strategic Marketing. 2010;18:553–572. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J., Carroll G.R., Hannan M.T. The liability of newness: Age dependence in organizational death rates. American Sociological Review. 1983;48(5):692–710. [Google Scholar]

- Gammeltoft P., Filatotchev I., Hobdari B. Emerging multinational companies and strategic fit: A contingency framework and future research agenda. European Management Journal. 2012;30(3):175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Habersang S., Küberling-Jost J., Reihlen M., Seckler C. A process perspective on organizational failure: A qualitative meta-analysis. Journal of Management Studies. 2019;56(1):19–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton E.A. An exploration of the relationship between loss of legitimacy and the sudden death of organizations. Group & Organization Management. 2006;31:327–358. [Google Scholar]

- Headd B. Redefining business success: Distinguishing between closure and failure. Small Business Economics. 2003;21:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Heracleous L., Werres K. On the road to disaster: Strategic misalignments and corporate failure. Long Range Planning. 2016;1:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- International Civil Aviation Organization . Montréal; Canada: 2020. Take-off: Guidance for air travel through the COVID-19 public health crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M.C. Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. The American Economic Review. 1986;76(2):323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Kücher A., Mayr S., Mitter C., Duller C., Feldbauer-Durstmüller B. Firm age dynamics and causes of corporate bankruptcy: Age dependent explanations for business failure. Review of Managerial Science. 2020;14(3):633–661. [Google Scholar]

- Lazonick W., Shin J.S. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2019. Predatory value extraction: How the looting of the business corporation became the US norm and how sustainable prosperity can Be restored. [Google Scholar]

- Lejano R.P., Shankar S. The contextualist turn and schematics of institutional fit: Theory and a case study from Southern India. Policy Sciences. 2013;46:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott J. Routledge; Abingdon: 2019. Corporate society: Class, property, and contemporary capitalism. [Google Scholar]

- Mellahi K., Wilkinson A. Organizational failure: A critique of recent research and a proposed integrative framework. International Journal of Management Reviews. 2004;5:21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Micelotta E., Lounsbury M., Greenwood R. Pathways of institutional change: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Management. 2017;43(6):1885–1910. [Google Scholar]

- Miller D. Configurations revisited. Strategic Management Journal. 1996;17(7):505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell W., Shaver J.M. What role do acquisitions play in Asian firms‟ global strategies? Evidence from the medical sector 1978-1995. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. 2002;19(4):489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R.R., Winter S.G. Belknap Press; Cambridge, MA: 1982. An evolutionary theory of economic change. [Google Scholar]

- Opinium Research . Opinium Research; London: 2020. Impact of coronavirus on UK SMEs. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira V., Temouri Y., Patnaik S., Mellahi K. Academy of Management Perspectives; 2020. Managing and preparing for emerging infectious diseases: Avoiding a catastrophe. in. press. [Google Scholar]

- Rider C.I., Negro G. Organizational failure and intraprofessional status loss. Organization Science. 2015;26:633–649. [Google Scholar]

- Sabherwal R., Hirschheim R., Goles T. The dynamics of alignment: Insights from a punctuated equilibrium model. Organization Science. 2001;12(2):179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Salaudeen A. African airlines lose $4.4 billion in revenue following the spread of coronavirus on the continent. 2020. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/19/africa/coronavirus-africa-airlines/index.html Retrieved 02.04.2020, from.

- Shepherd D.A. Learning from business failure: Propositions about the grief recovery process for the self-employed. Academy of Management Review. 2003;28:318–329. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard J.P. Strategy and bankruptcy: An exploration into organizational death. Journal of Management. 1994;20:795–833. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman B., Nickerson J., Freeman J. Profitability, transactional alignment and generalization mortality in the U.S. trucking industry. Strategic Management Journal. 1997;18:31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D. McGraw Hill; Chicago, IL: 1967. Organizations in action. [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill S., Amit R. Learning about failure: Bankruptcy, firm age, and the resource-based view. Organization Science. 2003;14(5):497–509. [Google Scholar]

- Volberda H.W., van der Weerdt N., Verwaal E., Stienstra M., Verdu A.J. Contingency fit, institutional fit, and firm performance: A metafit approach to organization–environment relationships. Organization Science. 2012;23(4):1040–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh M.W. A tidal wave of bankruptcies is coming. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/18/business/corporate-bankruptcy-coronavirus.html?smid=tw-share Retrieved 18.06.2020, from.

- Wenzel M., Stanske S., Lieberman M.B. Strategic responses to crisis. Strategic Management Journal. 2020;41:V7–V18. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsteller P. Trans states airlines to fold in April. 2020. https://www.flightglobal.com/strategy/trans-states-airlines-to-fold-in-april/137349.article Retrieved 02.04.2020, from.

- Wood G. Comparative capitalism, long energy transitions and the crisis of liberal markets. The Journal of Comparative Economic Studies. 2019;14:7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wood G., Wright M. Corporations and new statism: Trends and research priorities. Academy of Management Perspectives. 2015;29(2):271–286. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation report - 137. [Google Scholar]

- Worldometers Coronavirus cases. 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ Retrieved 13.05.2020, from.

- Zhang H., Amankwah-Amoah J., Beaverstock J. Toward a construct of dynamic capabilities malfunction: Insights from failed Chinese entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Research. 2019;98:415–429. [Google Scholar]