Significance

We present climate projections of population-weighted heat and cold exposure that directly and simultaneously account for greenhouse gas (GHG) and urban development-induced warming. Previous population heat and cold exposure estimates have not accounted for urban development-induced climate impacts, have neglected interactions between urban development-induced warming and GHG-induced climate change, and have used fixed temperature thresholds that may be inappropriate for some cities. We develop a more detailed and nuanced definition of extreme heat and cold exposure through key innovations, and our predicted exposure is substantially greater than previous assessments. Our results demonstrate that Sunbelt cities are projected to undergo the largest relative increase in population heat exposure to locally defined extreme heat conditions during the 21st century.

Keywords: heat exposure, cold exposure, climate change, climate adaptation, urban climate

Abstract

We use a suite of decadal-length regional climate simulations to quantify potential changes in population-weighted heat and cold exposure in 47 US metropolitan regions during the 21st century. Our results show that population-weighted exposure to locally defined extreme heat (i.e., “population heat exposure”) would increase by a factor of 12.7–29.5 under a high-intensity greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and urban development pathway. Additionally, end-of-century population cold exposure is projected to rise by a factor of 1.3–2.2, relative to start-of-century population cold exposure. We identify specific metropolitan regions in which population heat exposure would increase most markedly and characterize the relative significance of various drivers responsible for this increase. The largest absolute changes in population heat exposure during the 21st century are projected to occur in major US metropolitan regions like New York City (NY), Los Angeles (CA), Atlanta (GA), and Washington DC. The largest relative changes in population heat exposure (i.e., changes relative to start-of-century) are projected to occur in rapidly growing cities across the US Sunbelt, for example Orlando (FL), Austin (TX), Miami (FL), and Atlanta. The surge in population heat exposure across the Sunbelt is driven by concurrent GHG-induced warming and population growth which, in tandem, could strongly compound population heat exposure. Our simulations provide initial guidance to inform the prioritization of urban climate adaptation measures and policy.

Projections of urban development in the United States suggest that urban land coverage could reach up to 312,426 km2 by 2100, representing a 164% increase from the start-of-century urban extent (1). This urban expansion could have profound implications for natural ecosystems (2), carbon balance (3), population exposure to extreme temperatures (4), and human health and wellbeing (5). Hot and cold meteorological events are leading causes of all weather-related mortality (6) and morbidity (7), and quantification of population exposure to these events is critical to understanding the public’s vulnerability to climatic change (8, 9). Here, we use coupled urban-atmosphere simulations of the Continental United States (CONUS) to highlight metropolitan regions in which population-weighted exposure to hot and cold extremes will change most notably during the 21st century. Since population and climate are changing concurrently, human impact research requires consideration of “population heat (cold) exposure,” which is manifest through the intersection of climatic extremes and population distribution(s) (i.e., person hours of heat (cold) exposure = number of extreme heat (cold) hours × total population exposed to hot (cold) temperatures). Metropolitan-area projections of population heat and cold exposure can help planners and practitioners assess the relative significance of climate risks and provide guidance on the implementation of appropriate adaptation measures and policy interventions.

Previous CONUS-scale simulations of future hot and cold extremes have not directly and simultaneously accounted for the effects of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, population growth, and urban development (10–13). Urban development-induced warming impacts are often ignored in population heat exposure research (14), despite evidence that GHG and urban development-induced impacts can be of comparable magnitudes (15, 16), and indications that regional climate can amplify or decrease the intensity of urban development-induced local warming (13, 17, 18). The failure to include urban development-induced impacts in projections may lead to inaccurate assessments of the magnitude of population heat and cold exposure.

Jones et al. (10) previously reported that person hours of heat exposure to 35 °C days will increase by a factor of 4–6 across CONUS by 2070. However, the fundamental assumption that a “hot day” can be defined according to a fixed temperature threshold (i.e., 35 °C in all cities) across CONUS overlooks local human adaptation arising from physiological and/or behavioral factors (19). Notably, threshold temperatures at which excess mortality occur are well known to be regionally specific (14, 20). To facilitate meaningful place-based projections of changes in population heat and cold exposure, it is essential to apply locally defined definitions of hot and cold days across urban metropolitan regions. Motivated by these concerns, here we explicitly assess how impacts of GHG-induced warming, urban development, and population growth drive changes in population heat and cold exposure to locally defined hot and cold meteorological extremes during the 21st century. Our effort is concentrated on all events where the local threshold is exceeded and does not focus on consecutive extreme days (e.g., heat waves or cold waves), which are known to cause particularly large spikes in human mortality and morbidity (21, 22). We adopted this simplifying assumption because the accumulative effects of heat waves and cold waves cannot be accounted for in a single intuitive metric, such as person hours.

We use 10-y simulations conducted with the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) regional climate model dynamically coupled to an urban canopy model (13, 23, 24) to quantify start-of-century (2000–2009) and end-of-century (2090–2099) population heat and cold exposure in all major CONUS metropolitan regions. We define 47 metropolitan regions (also referred to hereafter as “cities”) based on their projected end-of-century urban extent (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). WRF simulations dynamically downscale the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 8.5 scenario from two independent global climate models (GCMs) with contrasting sensitivities to future GHG emissions and additionally incorporate urban development and population projections [Integrated Climate and Land Use Scenario [ICLUS] A2; Bierwagen et al. (1)] consistent with this emissions pathway. The simulations assume high-intensity urban development, population growth, and GHG emissions, meaning that our projections bound the upper limit of anticipated end-of-century population heat exposure (based on currently available datasets). The meteorological context (i.e., climate “forcing”) for the 20-km-resolution WRF simulations are provided by output from the bias-corrected Community Earth System Model (CESM) (25) and the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) (26) model.

Results

Projections of Hot Days.

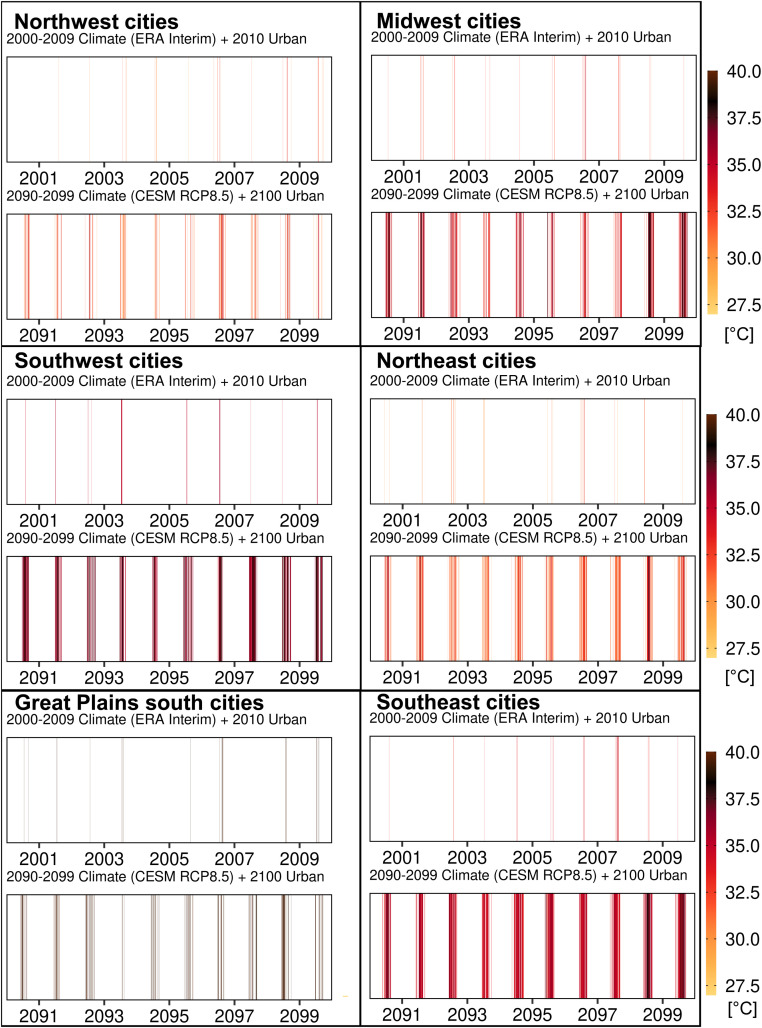

Our dynamically downscaled projections show that the frequency of hot days (defined as days exceeding the locally defined 99th percentile of 2000–2009 1500 local mean solar time [LMST] air temperature) is projected to increase across all CONUS regions during the 21st century under the RCP 8.5 GHG emissions pathway (Fig. 1). Urban areas located within the Southeast National Climate Assessment (NCA) region (see SI Appendix, Fig. S2 for map of NCA regions) are projected to undergo the largest increase in the number of hot days with an additional 71.6 ± 10.5 (CESM RCP 8.5 forcing) and 38.6 ± 14.4 (GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing) hot days per year by the end of this century. The number of hot days is also projected to increase notably in cities across the Southwest (53.7 ± 11.4 CESM RCP 8.5 forcing; 22.4 ± 11.4 GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing) and Great Plains south (48.6 ± 22.4 CESM RCP 8.5 forcing; 19.2 ± 15.5 GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing) NCA regions. Additionally, our projections indicate that average intensity of hot days would increase by 0.5 ± 0.2 °C (GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing) and 1.0 ± 0.4 °C (CESM RCP 8.5 forcing) under this scenario. The projections for individual cities reveal interregional variability in the frequency (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A) and intensity (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B) of hot days. For example, some of the most impacted cities are located in Florida, where upwards of 90 (CESM RCP 8.5 forcing) and 50 (GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing) hot days per year are projected by the end of this century.

Fig. 1.

Occurrence and intensity of hot days across US NCA regions derived from dynamical downscaling. Hot days are those that exceed the NCA region contemporary (2000–2009) 99th percentile of 3 PM LMST air temperature. The x axis represents a 10-y period. In each panel the top row represents 2000–2009 climate forcing with 2010 urban development and the bottom row represents 2090–2099 CESM RCP 8.5 climate forcing with 2100 urban development. Only urban areas from SI Appendix, Fig. S1 within each NCA region (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) are included. Occurrence of hot days for GFDL RCP 8.5 climate forcing is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3.

In addition to increased frequency and intensity of hot days, the average hot weather season (i.e., the temporal extent during which hot days occur) is projected to lengthen across all NCA regions except the Northwest (SI Appendix, Table S1). We project the largest broadening of the hot weather season across Northeast cities, with an average end-of-century hot weather season expansion of 73 d. Our findings point to an increased intensity and frequency of hot days in urban areas across CONUS during a 21st century driven by the combination of GHG-induced climate change and urban development. These drivers, in conjunction with population change, will determine the future characteristics of population heat exposure in CONUS cities.

Projected Population Heat Exposure (Person Hours of Heat Exposure).

To calculate population heat exposure, we tally all hours (regardless of date/time of occurrence) that exceed the local hot day threshold temperature (i.e., the 2000–2009 99th percentile of 1500 LMST air temperature) and multiply the number of projected hot hours by population. In this fashion, we capture the change in population heat exposure at the hourly scale in CONUS cities during the 21st century. To account for urban growth and population change, all simulations integrate ICLUS projections of building density, imperviousness, and population from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (1). During the 21st century, the combined effects of 90 y of urban development-induced warming, GHG-induced climatic warming, and population growth will increase the average number of person hours per year across CONUS from 5.2 ± 1.5 billion to 66.3 ± 16.9 billion for the GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing, and to as much as 154.1 ± 24.8 billion for the CESM RCP 8.5 forcing (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Approximately 60% of this heat exposure is projected to occur in major US cities such as New York City (NY), Washington DC, Atlanta (GA), Los Angeles (CA), Denver (CO), Chicago (IL), Miami (FL), and Dallas (TX). Most notably, the broader New York City region could experience an absolute increase in annual population heat exposure of 24.6 ± 4.4 billion person hours (CESM RCP 8.5 forcing), more than twice the absolute increase in population heat exposure than in any other metropolitan region in our sample.

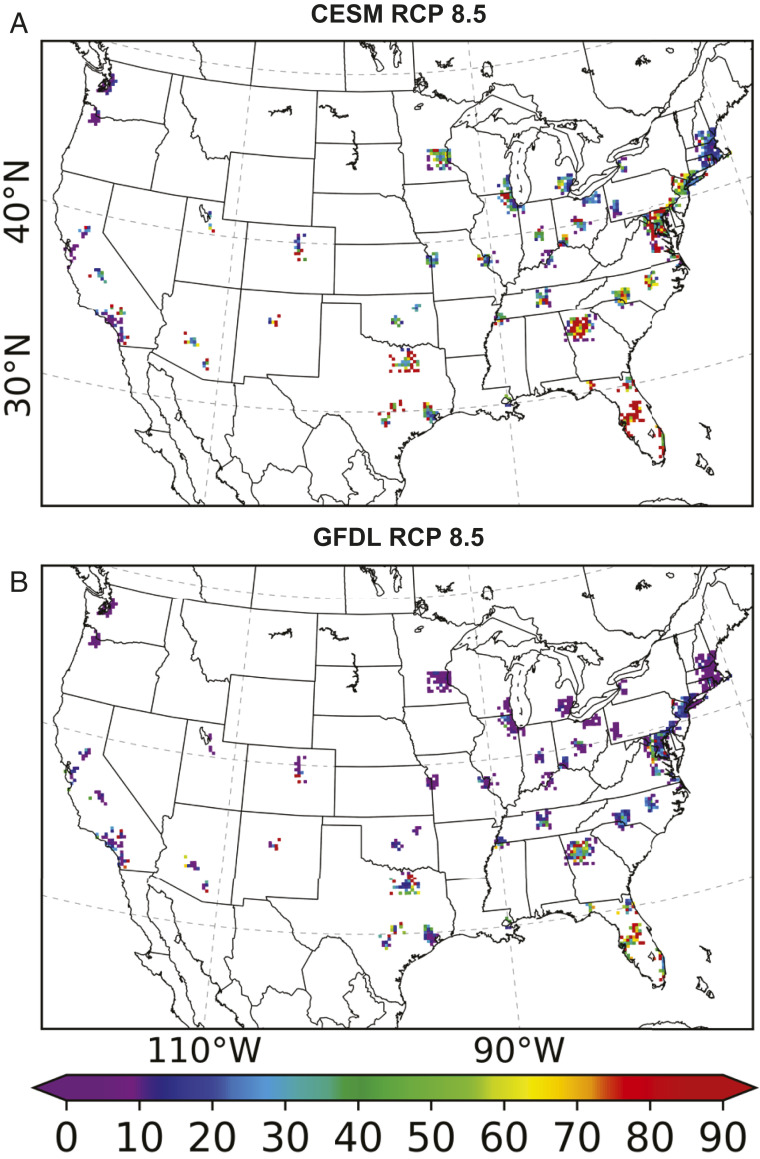

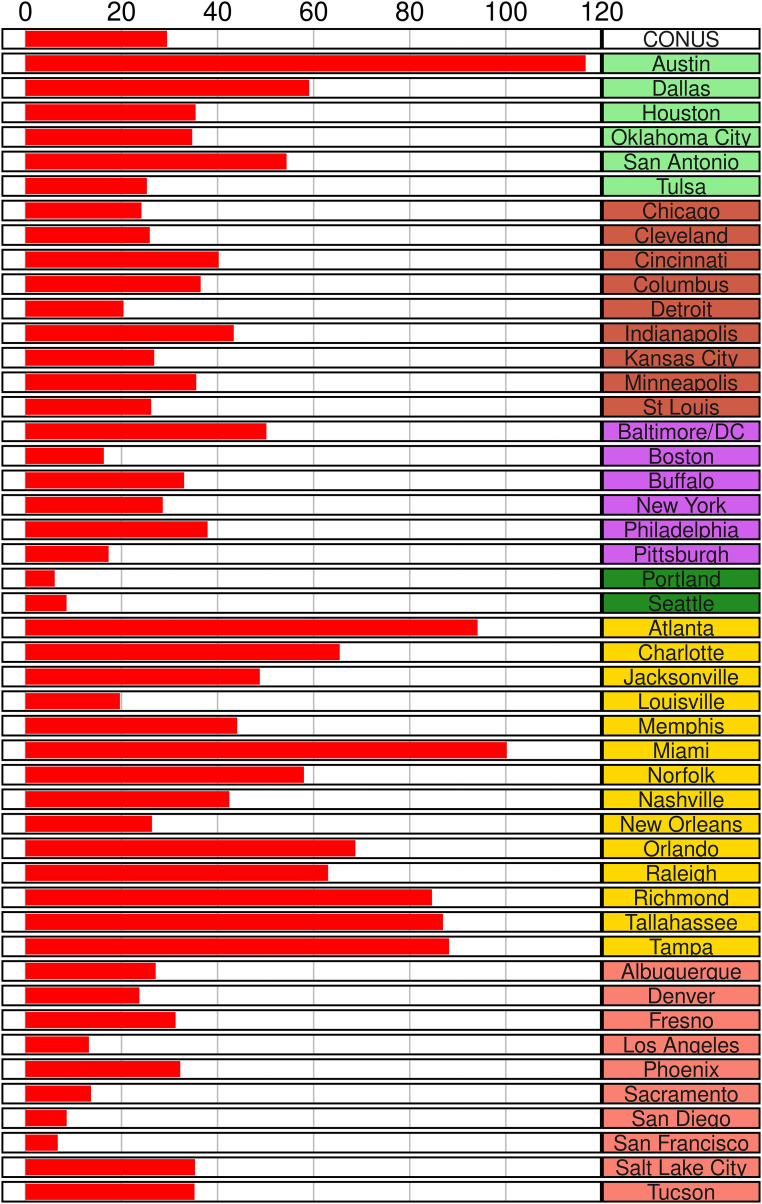

This growth in person hours implies that CONUS population heat exposure will increase during the 21st century by 12.7–29.5 times relative to start-of-century levels. Substantial spatial variability in the relative change in projected population heat exposure is evident across cities, with some areas in the US Sunbelt and Northeast urban corridor experiencing a 90-fold increase compared to start-of-century levels (Fig. 2). The spatial patterns described are consistent for both GCM forcings, although results from the GFDL RCP 8.5 forced simulation are more muted than CESM RCP 8.5. Overall, results from dynamical downscaling of two independent GCM forcings with distinct sensitivities to GHG-induced climate change, indicate agreement that Sunbelt cities are projected to see the largest relative increase in population heat exposure during the 21st century (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). See SI Appendix, Table S2 for an overview of projected relative changes in metropolitan area heat exposure.

Fig. 2.

The relative increase in population heat exposure during the 21st century (i.e., 2090–2099 divided by 2000–2009 person hours) derived from dynamical downscaling that combines 90 y of projected GHG-induced climate change, urban development, and population growth, with both (A) CESM RCP 8.5 (Top) and (B) GFDL RCP 8.5 (Bottom) climate forcings shown. Person hours are calculated based on exposure to locally defined start-of-century 99th percentile of 1500 LMST air temperature. Only urban grid squares from the 47 cities included in our analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) are shown.

Fig. 3.

The relative increase in population heat exposure during the 21st century (i.e., 2090–2099 divided by 2000–2009 person hours) resulting from a combination of 90 y of projected GHG-induced climate change, urban development, and population growth. Projections are derived from dynamical downscaling of the CESM RCP 8.5 forcing. Note that the city names used are principally intended as identifiers for the bounding boxes used (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), which extend (in many cases) beyond traditional municipal or city boundaries. The color coding (Right) corresponds to NCA climate regions (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Results for the GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6.

Our projections of population heat exposure are substantially greater than previous work, which predicted an increase in person hours of 4–6 times between 1980–2010 and 2040–2070 (10). In contrast to our method, their approach calculates population heat exposure at a daily timestep (not hourly, as utilized here) and uses a fixed temperature threshold of 35 °C to define hot days (not a locally defined relative threshold). Since our population heat exposure estimates are notably larger than Jones et al. (10), we replicate their analysis using a fixed temperature threshold with our own regional climate simulation output. Using their approach, we find that start-of-century population heat exposure increases during the 21st century by 6.3–10.2 times, which is two- to threefold less than what we report using relative heat thresholds (i.e., Fig. 3). This finding is consistent with previous research, utilizing GCMs, which has found discrepancies in the frequency of projected heat events using fixed versus relative temperature thresholds [e.g., see Wobus et al. (27)]. Overall, four factors in the present study lead to findings that diverge from those of Jones et al. (10): 1) our simulations include 30 additional y of GHG-induced climate warming; 2) the use of an explicit representation of urban development-induced temperature impacts; 3) the use of locally defined hot conditions rather than a fixed temperature threshold; and 4) the use of hourly data rather than daily maximum temperatures. Importantly, by accounting for hourly temperatures, we reveal the potential impact of a lengthening period throughout the day that individuals are exposed to extreme heat conditions under a future, warmer climate.

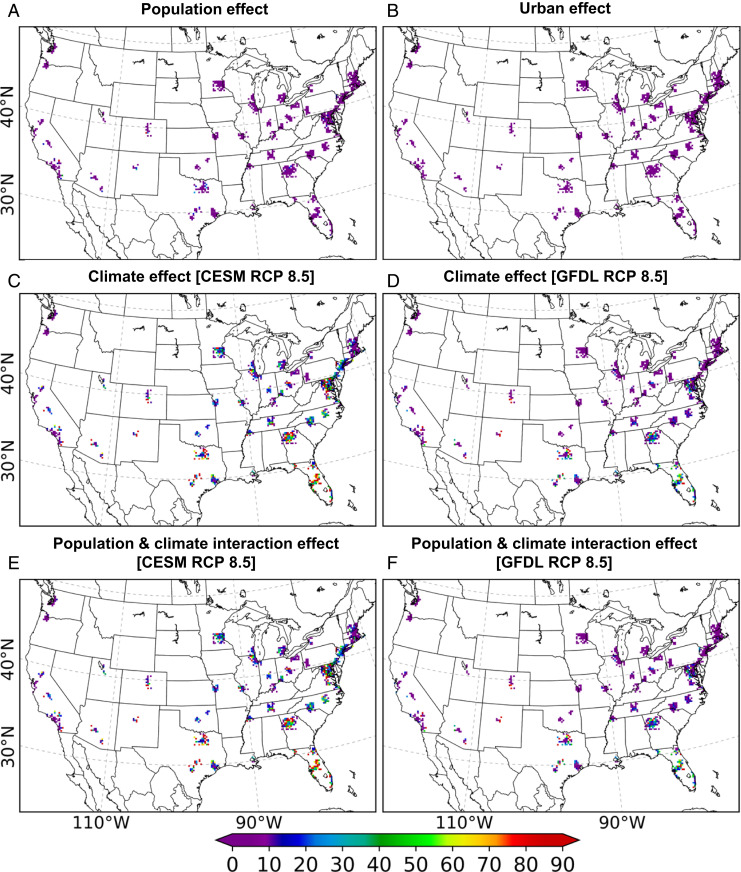

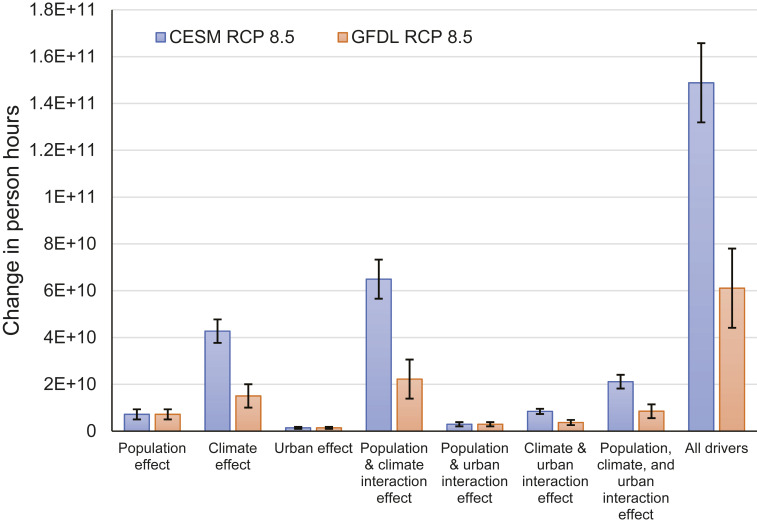

It is instructive to partition the components that cause changes in population heat exposure. Following Stein and Alpert (28), we isolate seven driving factors (Table 1): three main drivers and four interactions between those drivers (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Among the three independent drivers (i.e., changing one variable only), the climate effect is largest, contributing 24.6–28.7% of the total change in CONUS population heat exposure during the 21st century (Fig. 5). Although the population effect (i.e., changing population only) is relatively small, the synergistic impact of GHG-induced climate warming and population growth (i.e., the population and climate interaction effect; Fig. 4 E and F) is the largest driving force of all (36.4–43.6% of the total change). Therefore, population growth compounds the impacts of GHG-induced warming across almost all US cities (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A and B) as a growing population increases the number of people exposed to hot conditions. Since population is not dynamically coupled to GHG-induced climate or urban development-induced effects in our model, it essentially acts as a multiplier; i.e., the population and climate interaction effect is representative of “the change in the number of hot hours due to GHG-induced warming only” multiplied by “the change in population.”* The climate and population interaction effect is projected to be greatest in cities across the Southeast NCA region where it will contribute 50.4% of the total change in heat exposure under the CESM RCP 8.5 climate forcing and 44.3% under the GFDL RCP 8.5 climate forcing (see SI Appendix, Table S3 A and B for metropolitan region-specific projections of population heat exposure drivers).

Table 1.

Summary of drivers of population heat and cold exposure

| Driver | Description |

| 1) Population effect | The direct effect of increasing population from 2010 to 2100 levels with other variables held constant (Fig. 4A). |

| 2) Urban effect | The direct effect of increasing urban development (i.e., the physical growth of cities) from 2010 to 2100 levels with other variables held constant (Fig. 4B). |

| 3) Climate effect | The direct effect of increasing GHG concentrations from 2010 to 2100 levels with other variables held constant (Fig. 4 C and D). |

| 4) Population and climate interaction* effect | The interaction effect that occurs when GHG concentrations (driver #3) and population (driver #1) are simultaneously increased from 2010 to 2100 levels (Fig. 4 E and F). |

| 5) Population and urban interaction* effect | The interaction effect that occurs when population (driver #1) and urban development (driver #2) are simultaneously increased from 2010 to 2100 levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). |

| 6) Climate and urban interaction effect | The interaction effect that occurs when GHG concentrations (driver #3) and urban development (driver #2) are simultaneously increased from 2010 to 2100 levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 B and C). |

| 7) Population and climate and urban interaction* effect | The interaction effect that occurs when all three variables (driver #1, driver #2, and driver #3) are simultaneously increased from 2010 to 2100 levels (Fig. 8 D and E). |

We note that as population is not dynamically coupled to the other variables; strictly speaking, it is not interacting with the other variables. The term “interaction” is used here as a naming convention, referring to any change in population exposure resulting from synergistic/antagonistic effects of changing two or more variables simultaneously; however, the term does not imply an explicitly simulated dynamical coupling.

Fig. 4.

Relative increase in population heat exposure during the 21st century (i.e., 2090–2099 divided by 2000–2009 person hours) resulting from individual drivers: (A) population growth (“population effect”), (B) urban development (“urban effect”), (C) GHG warming with CESM RCP 8.5 forcing (“climate effect”), (D) GHG-warming with GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing (climate effect), (E) the interaction effect of simultaneous population growth and GHG-induced warming with CESM RCP 8.5 forcing (“population and climate interaction effect”) and (F) the interaction effect of simultaneous population growth and GHG-induced warming with GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing (population and climate interaction effect). Drivers of heat exposure are derived from dynamical downscaling. Additional drivers not shown here and provided in SI Appendix, Fig. S8.

Fig. 5.

CONUS annual average change in population heat exposure during the 21st century (2090–2099 compared with 2000–2009) resulting from individual drivers and their interactions. Projections are derived from dynamical downscaling of CESM and GFDL RCP 8.5 climate forcing in combination with ICLUS urban development and population projections. Uncertainty (±1 SD) due to annual variability is shown.

The urban effect is small compared to other drivers, making up 1.0–2.3% of the total population heat exposure impact in the aggregate. However, the urban effect interacts with GHG-induced climatic change (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 B and C) to slightly increase the contribution of the urban effect on population heat exposure from 1.0 to 2.3% to 6.7–8.4%. Furthermore, population growth and the urban effect (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A) also interact to slightly increase population heat exposure. The sum of the urban effect, the urban and climate interaction effect, and the urban and population interaction effect equate to 8.6–13.2% of the total end-of-century population heat exposure. Additionally, we find that there is a substantial (comprising ∼14% of total heat exposure), and previously unaccounted for, three-way interaction between the urban development-induced warming, GHG-climate change, and population growth (SI Appendix, Fig. 7 D and E). These results illustrate that, independently, urban development does not substantially increase population heat exposure. However, urban development-induced warming can interact with GHG-induced climatic warming and population growth, leading to nonnegligible impacts on total population heat exposure.

Our analysis is primarily focused on population heat exposure to extreme daytime temperatures (i.e., hot hours). However, the impacts of urban development on air temperature are usually greatest at night, especially in the case where previously undeveloped rural areas become urbanized [see Krayenhoff et al. (13)]. In recognition of this fact, we also calculate the increase in population exposure to extreme nighttime temperatures (i.e., the 99th percentile of start-of-century 0300 LMST air temperature) due to urban development-induced effects. For nighttime extreme temperatures, the urban effect remains relatively small, contributing less than 5% of the total population heat exposure impact (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). However, this does not mean that the nighttime urban development-induced air-temperature impacts are small. At this scale, the largest urban-warming effect occurs in areas where population is low (i.e., on the urban fringe, where most urban expansion occurs). Therefore, the net impact of urban development on population heat exposure is small compared to GHG-induced warming, which affects all areas in the city approximately evenly. To illustrate this concept, we calculated the increase in number of hot nights due to urban development only; we find substantial increases of up to 20 hot nights per year (i.e., a fivefold increase in the number of hot nights) in expanding urban areas across the Sunbelt and Northeastern corridor (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). The paradox of nocturnal urban development-induced effects, at this scale, is that the effect is largest in areas where population is lowest, meaning that although urban development-induced impacts can have large warming effects on local nocturnal temperatures, they do not impact the total population heat exposure as much as anticipated.

Projected Cold Exposure.

Our results indicate that the frequency of cold nights (defined as nights colder than the 1st percentile of 2000–2009 0300 LMST air temperature) will decrease by the end-of-century across all metropolitan regions with fewer than 2.8 cold nights per year predicted in all regions, with the CESM RCP 8.5 forcing (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A and Table S4). However, under the GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing the frequency of end-of-century cold nights will remain commensurate with (or slightly increase) relative to start-of-century conditions across the Great Plains south, Northwest, and Southwest regions (SI Appendix, Fig. S11B). The largest increase in cold nights is predicted to occur in Denver (CO) with 4.7 ± 1.2 additional cold nights per year by the end-of-century. Although cold nights are projected to decrease across many regions, the total change in population cold exposure is projected to marginally increase by factors of 1.3 (CESM RCP 8.5 forcing) and 2.2 (GFDL RCP 8.5 forcing) relative to start-of-century levels (SI Appendix, Table S5). Population cold exposure slightly increases in the aggregate because the impact of population growth (which increases population cold exposure) surpasses the decrease in cold hours, particularly across the US Sunbelt (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). However, we project that end-of-century population heat exposure will increase by 10–15 times more, in absolute terms, than population cold exposure across CONUS metropolitan regions.

Discussion and Conclusion

We present an internally consistent analysis of end-of-century population heat and cold exposure across major US metropolitan regions by simultaneously accounting for the interaction between GHG-induced climate change, urban development, and population growth. This work advances understanding of the regional variation of future population heat and cold exposure. We achieve this through three important innovations: 1) We project hot and cold exposure using urban temperatures that are representative of city-specific climatic conditions [i.e., “subgrid urban temperature;” see Krayenhoff et al. (13)]; 2) We use locally defined heat thresholds for each major metropolitan region, rather than fixed thresholds of hot/cold conditions; and 3) We report our findings at the scale of metropolitan regions rather than averages across climatic regions, which is a more helpful framework for guiding planners and practitioners tasked with adapting to future climatic extremes. This analysis reveals the CONUS metropolitan regions that are expected to experience the largest relative and absolute changes in population heat and cold exposure.

We emphasize the following caveats with regards to interpretation of this analysis. The simulations are designed to bracket the potential effects of GHG-induced climate change, urban development, and population growth on population heat and cold exposure. Accordingly, the climate and urban development scenarios selected represent high-intensity future emissions (i.e., RCP 8.5 emissions pathway), population growth, and urban development (ICLUS A2) futures. Furthermore, since we calculate population heat and cold exposure using outdoor urban air temperatures, our projections represent a hypothetical maximum potential population heat and cold exposure, as urban inhabitants can seek refuge indoors during extreme thermal conditions (29). The results reported herein effectively bound the upper limit of anticipated end-of-century population heat exposure. Nevertheless, the importance of holistically characterizing the motley drivers of thermal exposure is of considerable import for individual municipalities to ensure effective development of coping strategies and adaptation to a significantly warmer future environment.

The largest absolute changes in population heat exposure are projected to occur in major metropolitan regions such as New York City, Washington DC, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Denver, Chicago, Miami, and Dallas, with these cities making up ∼60% of the total increase in projected heat exposure across CONUS. Of the 47 metropolitan regions we considered, there are 29 that are projected, by dynamical downscaling of CESM and GFDL RCP 8.5, to experience a 10-fold (or more) increase in population heat exposure by the end of the 21st century. We categorize these locations with the largest relative change in population heat exposure as the “worst-impacted” cities. Of the 29 worst-impacted cities, 23 are located in the US Sunbelt. This result was confirmed by dynamical downscaling of two different GCM forcings with contrasting GHG sensitivities. These projections of population heat exposure can provide preliminary guidance on the prioritization of municipal adaptation measures and policy. Ascertaining which adaptation polices will be most effective in different cities and how to utilize infrastructure-based measures (e.g., reflective construction materials), potentially in combination with social mechanisms (e.g., provision of cooling centers), is a critical question for future research. Additionally, the effectiveness of adaptation measures should be considered and evaluated across different neighborhoods within cities to find the locations where heat-mitigating measures are needed and will be effective (30).

Adapting to climatic warming and choosing the optimum combination of adaptation measures and policies is a major challenge for cities globally, not just those in CONUS. Cities throughout the developing world, many of which are projected to expand rapidly in the coming decades [e.g., India, China, and sub-Saharan Africa; Huang et al. (31)], will likely experience rapid growth in population heat exposure during the 21st century. The substantial impacts of this rapid growth across the developing world on biodiversity and carbon sinks have been quantified and described in detail (3), and yet the nature and complex causation of changing human population heat and cold exposure across the developing world remains largely unknown. Our analysis demonstrates population heat exposure would markedly increase across CONUS in rapidly growing regions such as the US Sunbelt under the RCP 8.5 emissions pathway. In the rapidly urbanizing developing world, the growing burden of exposure is likely to be considerably greater than is reported here for CONUS.

Importantly, little is known about the challenges that cities in the developing world face, as much of our urban knowledge comes from research focused on developed world cities (32). The analysis presented here should therefore be replicated globally, especially across the developing world, so that the changing weight of heat and cold exposure and its drivers can be quantified and better understood in more locations and city archetypes. Analysis of more cities could facilitate the development of a typology of city exposure and adaptation profiles. The typology would provide a framework for cities without sufficient resources (computational/financial) to create data-driven heat adaptation policies and infrastructure plans based on known best practices from analogous locations.

Materials and Methods

We utilize simulation data from Krayenhoff et al. (13), who applied Version 3.6 of the Advanced Research WRF (ARW) modeling system (24) coupled to a single-layer urban canopy scheme (23) to dynamically downscale start-of-century (2000–2009) and end-of-century (2090–2100) global climatic conditions to 20-km resolution across the entire CONUS. All model integrations include 1 mo of spin-up time prior to each decadal period of interest. The 20-km resolution WRF domain contains 310 × 190 grid squares in the east–west and north–south directions, respectively. Population heat and cold exposure was calculated for all grid squares that contain impervious surfaces > 0 (i.e., urban grid squares) within the 47 metropolitan regions defined in SI Appendix, Fig. S1.

Start-of-century atmospheric boundary conditions are obtained from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) interim reanalysis ("ERA-interim") product (33). For end-of-century conditions, the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5 CESM RCP 8.5 (25) and GFDL RCP 8.5 (26) data were used to define atmospheric boundary conditions. CESM and GFDL RCP 8.5 have contrasting sensitivities to GHG emissions. By using dynamically downscaled data from two independent GCMs we account for GCM uncertainty when evaluating future impacts of climate.

To represent urban temperatures when the model resolution is 20 km, we use a subgrid temperature diagnosis (13) to explicitly resolve urban temperatures (TCITY). We use TCITY to define hot and cold population exposure, meaning our estimates of temperature correspond more directly with conditions experienced by urban dwellers than previous continental-scale efforts (10–12, 34). We evaluated the accuracy of TCITY projections against 10 y of observed mean, minimum, and maximum air-temperature data. We evaluated TCITY in all 47 metropolitan regions, focusing on the summer (June, July, August) and winter (December, January, February) seasons. Given the spatial modeling scale and the limitations of evaluation data, we find broadly satisfactory model performance across most NCA regions (see SI Appendix, Figs. S13–S18 and Supplementary Text for details).

WRF grid squares are divided into urban and natural fractions, with the urban (impervious) areas modeled by the single-layer urban canopy model and the natural areas handled by the Unified-Noah land surface model. Projections of urban building density, impervious fraction, and population come from the US EPA ICLUS projections (1, 13, 35). ICLUS projections are based on the socioeconomic storylines from the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES). For the ICLUS dataset, county-level population growth projections of the United States for each SRES scenario were derived from the 2010 US Census and other supplementary data. Here, we use the A2 ICLUS projection, which closely mirrors the RCP 8.5 scenario of future GHG emissions. The A2 scenario describes the highest projected growth in US urban land cover (projected to reach 312,426 km2 by 2100; this is approximately equal to the area of Arizona) and population (projected to reach 690 million by 2100). Therefore, our projections of population exposure are representative of the most aggressive urban development, population growth, and GHG-induced warming scenarios. Our results should be interpreted as an upper limit of potential end-of-century population heat exposure based on currently available projections of urban development, population growth, and GHG-induced climatic change.

We define hot days and cold nights for each city using the locally defined contemporary (i.e., 2000–2009) 99th percentile daily maximum and 1st percentile daily minimum TCITY (1500 LMST and 0300 LMST are used as proxies for maximum and minimum here). The hot-day and cold-night thresholds are calculated from the 10-y distribution of spatially averaged 1500/0300 LMST urban temperatures (i.e., TCITY) from the start-of-century urban area. To calculate person hours, we first calculated hot hours by linearly interpolating WRF TCITY output from the simulated 3-hourly output to 1-hourly frequency, and then counted all hours (regardless of timing) that exceed the hot-day temperature threshold. For each grid square, hot hours are then converted to person hours by multiplying by population interpolated at the same spatial resolution as WRF.

We extracted person hours for each metropolitan region using the bounding boxes defined in SI Appendix, Fig. S1. Bounding boxes were subjectively defined to include all projected end-of-century urban development. As the metropolitan and municipal boundaries of future cities are unknown, we define bounding boxes for each urban metropolitan region using a subjective approach. We define boxes that enclose all contiguous urban grid squares around the city/metropolitan region of interest. While these bounding boxes do not correspond to contemporary metropolitan or municipal boundaries, they do provide a useful framework for comparing city population heat-exposure drivers across the 21st century.

To calculate drivers of population heat exposure, we use the factor separation method of Stein and Alpert (28). For clarity, we first define the following naming conventions of simulations conducted by Krayenhoff et al. (13) (Table 2). The seven drivers of population exposure are computed for each grid square as follows:

-

1)

-

2)

-

3)

-

4)

-

5)

-

6)

-

7)

Table 2.

Description of WRF simulations

| Simulation name | Simulation description |

| SIMCONTROL | 2000–2009 climate forcing with 2010 urban development and 2010 population |

| SIMPOPULATION | 2000–2009 climate forcing with 2010 urban development and 2100 population |

| SIMCLIMATE | 2090–2099 climate forcing with 2010 urban development and 2010 population |

| SIMURBAN | 2000–2009 climate forcing with 2100 urban development and 2010 population |

| SIMPOPULATION+CLIMATE | 2090–2099 climate forcing with 2010 urban development and 2100 population |

| SIMPOPULATION+URBAN | 2000–2009 climate forcing with 2100 urban development and 2100 population |

| SIMCLIMATE+URBAN | 2090–2099 climate forcing with 2100 urban development and 2010 population |

| SIMPOPULATION+CLIMATE+URBAN | 2090–2099 climate forcing with 2100 urban development and 2100 population |

Bold text indicates conditions changed from the control state. Note: “CLIMATE” simulations were conducted via dynamical downscaling with CESM RCP 8.5 and GFDL RCP 8.5 climate forcings.

We used TCITY to calculate these factors in all instances except when 2100 population and 2010 urban development are combined (e.g., population effect). Across the CONUS domain there are ∼500 (out of 3,256 total) grid squares that contain no urban land cover at the start-of-century and become urbanized by the end-of-century (i.e., “urban expansion” grid cells). If 2010 urban development is simulated, there is no TCITY value diagnosed in urban expansion grid squares. Therefore, for expansion grid cells, when computing drivers that combine end-of-century population and start-of-century urban development, we use the default WRF temperature (“T2”) rather than TCITY.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF Sustainability Research Network Cooperative Agreement 1444758, the Urban Water Innovation Network, and NSF Grant SES-1520803. We acknowledge support from Research Computing at Arizona State University for the provision of high-performance supercomputing services. Additionally, we thank the three anonymous referees for helpful and constructive comments.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*This concept only applies independently for each model grid square.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2005492117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

Regional climate simulation output data used in this study are accessible at https://erams.com/public_data/climate#wrf_asu (36). Population heat and cold exposure data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Bierwagen B. G. et al., National housing and impervious surface scenarios for integrated climate impact assessments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 20887–20892 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu J., Urban ecology and sustainability: The state-of-the-science and future directions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 125, 209–221 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seto K. C., Güneralp B., Hutyra L. R., Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16083–16088 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Middel A., Krayenhoff E. S., Micrometeorological determinants of pedestrian thermal exposure during record-breaking heat in Tempe, Arizona: Introducing the MaRTy observational platform. Sci. Total Environ. 687, 137–151 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers S. S., Planetary health: Protecting human health on a rapidly changing planet. Lancet 390, 2860–2868 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson B. G., Bell M. L., Weather-related mortality: How heat, cold, and heat waves affect mortality in the United States. Epidemiology 20, 205–213 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye X. et al., Ambient temperature and morbidity: A review of epidemiological evidence. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 19–28 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebi K. L., Semenza J. C., Community-based adaptation to the health impacts of climate change. Am. J. Prev. Med. 35, 501–507 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones B., Tebaldi C., O’Neill B. C., Oleson K., Gao J., Avoiding population exposure to heat-related extremes: Demographic change vs climate change. Clim. Change 146, 423–437 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones B. et al., Future population exposure to US heat extremes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 652–655 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zobel Z., Wang J., Wuebbles D. J., Kotamarthi V. R., High‐resolution dynamical downscaling ensemble projections of future extreme temperature distributions for the United States. Earths Futur. 5, 1234–1251 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oleson K. W., Anderson G. B., Jones B., McGinnis S. A., Sanderson B., Avoided climate impacts of urban and rural heat and cold waves over the U.S. using large climate model ensembles for RCP8.5 and RCP4.5. Clim. Change 146, 377–392 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krayenhoff E. S., Moustaoui M., Broadbent A. M., Gupta V., Georgescu M., Diurnal interaction between urban expansion, climate change and adaptation in US cities. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 1097–1103 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasparrini A. et al., Projections of temperature-related excess mortality under climate change scenarios. Lancet Planet. Health 1, e360–e367 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgescu M., Moustaoui M., Mahalov A., Dudhia J., Summer-time climate impacts of projected megapolitan expansion in Arizona. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 37–41 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Georgescu M., Morefield P. E., Bierwagen B. G., Weaver C. P., Urban adaptation can roll back warming of emerging megapolitan regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 2909–2914 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li D., Bou-Zeid E., Synergistic interactions between Urban heat Islands and heat waves: The impact in cities is larger than the sum of its parts. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 52, 2051–2064 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott A. A., Waugh D. W., Zaitchik B. F., Reduced Urban heat island intensity under warmer conditions. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arbuthnott K., Hajat S., Heaviside C., Vardoulakis S., Changes in population susceptibility to heat and cold over time: Assessing adaptation to climate change. Environ. Heal. 15, 74–93 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karner A., Hondula D. M., Vanos J. K., Heat exposure during non-motorized travel: Implications for transportation policy under climate change. J. Transp. Health 2, 451–459 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitman S. et al., Mortality in Chicago attributed to the July 1995 heat wave. Am. J. Public Health 87, 1515–1518 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fouillet A. et al., Excess mortality related to the August 2003 heat wave in France. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 80, 16–24 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kusaka H., Kondo H., Kikegawa Y., Kimura F., A simple single-layer urban canopy model for atmospheric models: Comparison with multi-layer and slab models. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 101, 329–358 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skamarock W. C., Klemp J. B., A time-split nonhydrostatic atmospheric model for weather research and forecasting applications. J. Comput. Phys. 227, 3465–3485 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monaghan A. J., Steinhoff D. F., Bruyere C. L., Yates D., “NCAR CESM global bias-corrected CMIP5 output to support WRF/MPAS research.” Research Data Archive National Center Atmospheric Research Computational Information Systems Laboratory, Boulder. DOI: 10.5065/D6DJ5CN4. Accessed 29 November 2016. [DOI]

- 26.Dunne J. P. et al., GFDL’s ESM2 global coupled climate–Carbon earth system models. Part I: Physical formulation and baseline simulation characteristics. J. Clim. 25, 6646–6665 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wobus C. et al., Reframing future risks of extreme heat in the United States. Earths Futur. 6, 1323–1335 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stein U., Alpert P., Factor separation in numerical simulations. J. Atmos. Sci. 50, 2107–2115 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palecki M. A., Changnon S. A., Kunkel K. E., The nature and impacts of the July 1999 heat wave in the Midwestern United States: Learning from the lessons of 1995. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 82, 1353–1368 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Broadbent A. M., Krayenhoff E. S., Georgescu M., Efficacy of cool roofs at reducing pedestrian-level air temperature during projected 21st century heatwaves in Atlanta, Detroit, and Phoenix (USA). Environ. Res. Lett. (2020) in press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang K., Li X., Liu X., Seto K. C., Projecting global urban land expansion and heat island intensification through 2050. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 114037 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagendra H., Bai X., Brondizio E. S., Lwasa S., The urban south and the predicament of global sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 1, 341–349 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 33.European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts ERA-Interim Project Laboratory, Research data archive at the national center for atmospheric research computational and information systems (2009). https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets/reanalysis-datasets/era-interim. Accessed 29 November 2016.

- 34.Wuebbles D. J. et al., Climate Science Special Report, Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume 1, (United States Global Change Research Program, Washington, D.C, 2017), doi: 10.7930/J0J964J6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tools ICLUS. and Datasets (Version 1.3.2, US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., 2010).

- 36.Krayenhoff E. S., Moustaoui M., Broadbent A. M., Gupta V., Georgescu M., ASU WRF Climate Data. eRAMS Portal. https://erams.com/public_data/climate#wrf_asu. Deposited 15 August 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Regional climate simulation output data used in this study are accessible at https://erams.com/public_data/climate#wrf_asu (36). Population heat and cold exposure data are available upon reasonable request.