Significance

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a well-studied organism, which is used as a model organism for studying eukaryal biology and as a cell factory for the production of fuels, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. For both applications, the way that the cell utilizes its finite protein resource and how those inherent trade-offs manifest themselves is of interest, not least for their impact on cellular metabolism. Here we elucidate how alterations of protein-allocation allow for S. cerevisiae to increase its growth rate. Our results on cellular proteome-allocation may aid the engineering of more efficient strains in industrial biotechnology as well as improve our understanding toward phenotypes of cancer cells that grow faster than normal cells.

Keywords: systems biology, metabolic engineering, amino acid metabolism, protein translation

Abstract

Several recent studies have shown that the concept of proteome constraint, i.e., the need for the cell to balance allocation of its proteome between different cellular processes, is essential for ensuring proper cell function. However, there have been no attempts to elucidate how cells’ maximum capacity to grow depends on protein availability for different cellular processes. To experimentally address this, we cultivated Saccharomyces cerevisiae in bioreactors with or without amino acid supplementation and performed quantitative proteomics to analyze global changes in proteome allocation, during both anaerobic and aerobic growth on glucose. Analysis of the proteomic data implies that proteome mass is mainly reallocated from amino acid biosynthetic processes into translation, which enables an increased growth rate during supplementation. Similar findings were obtained from both aerobic and anaerobic cultivations. Our findings show that cells can increase their growth rate through increasing its proteome allocation toward the protein translational machinery.

Proteins are the workhorses of cells ensuring metabolism, signaling, structural integrity, stress response, transport, repair, transcription, and translation of genomic information. Depending on environmental conditions, tightly regulated transcription and translation enable the cell to fine-tune production of proteins for these different cellular processes (1, 2). Through demand, the cell may therefore optimize the construction of its proteome and allocate resources to where it serves best. However, the total amount of protein within a cell is obviously finite and the cell therefore needs to balance the allocation of proteins to the different processes appropriately. Due to this proteome constraint, the cell will often need to provide trade-offs between different cellular processes, i.e., if one process will demand more protein, this will have to be at the expense of another process (3, 4). With many different pathways and processes operating simultaneously in the cell, and with ∼4,500 proteins being expressed to support these processes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (5) at any given time, the orchestration of proteome allocation is crucial for ensuring proper cellular function and proliferation. As a consequence, enabling the optimization of the proteome usage could be of great benefit for metabolic engineering (6), via engineering of enhanced platform strains with more proteome mass available for heterologous pathways.

Cellular proteome allocation, and more specifically enzymatic constraints and its potential effects, have in recent years been investigated in silico with, for example, protein-constrained genome-scale metabolic models of both Escherichia coli (7) and S. cerevisiae (8, 9). To investigate this and expand our insight on proteome allocation, we cultivated S. cerevisiae, an important model organism as well as a widely used cell factory, in minimal medium or in rich medium, which is minimal medium plus supplementation of amino acids commonly present in medium for protein production (10), and investigated reallocations in the proteome and its potential impact on central and amino acid metabolism (Fig. 1A). Our analysis showed that as cellular growth rate is limited by ribosomal capacity, cells can grow faster in rich medium due to proteome reallocation from amino acid biosynthesis to translational machinery.

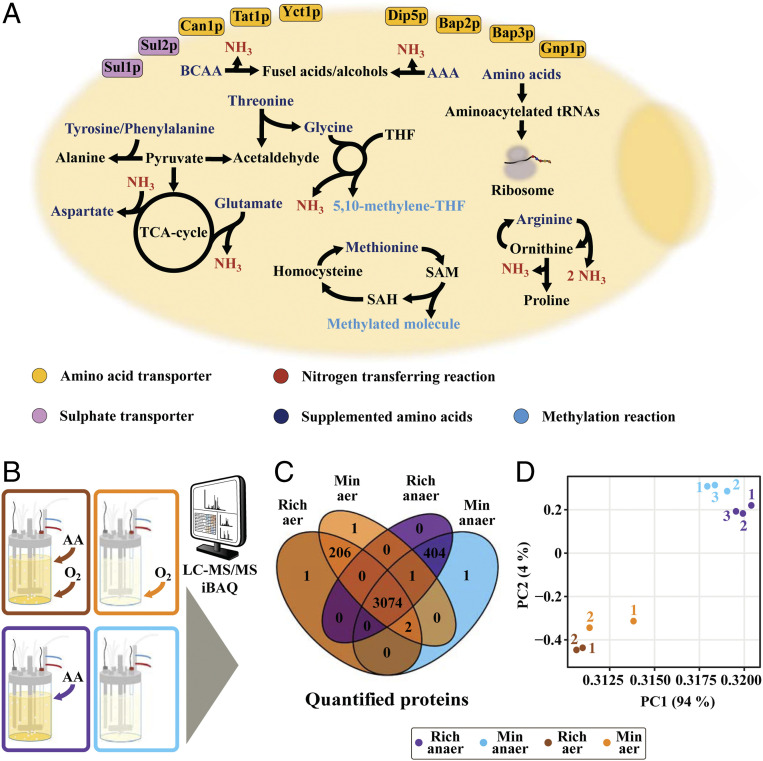

Fig. 1.

Experimental set-up. (A) Schematic of selected metabolic reactions (BCAA - branched chained amino acids, AAA - aromatic amino acids, THF - tetrahydrofolate, TCA - tricarboxylic acid), in S. cerevisiae, involving the 14 supplemented amino acids (Asp, Arg, Glu, Gly, His, Ile, Leu, Lys, Met, Phe, Thr, Trp, Tyr, Val). Affected transporters during cultivations in rich medium are highlighted. (B) S. cerevisiae was cultivated in batch-phase, in well-controlled bioreactor conditions, and quantitative proteomics were analyzed for cells grown in aerobic and anaerobic conditions, with our without amino acid supplementation. (C) The allocation of 3,690 proteins was quantified for each of the 4 conditions, with a substantial overlap between all conditions. (D) PCA (principal component analysis)-plot highlighting similarities between individual replicates for examined conditions, at the proteomic level.

Yeast Grows Faster in Rich Medium under Both Aerobic and Anaerobic Growth Conditions

Yeast was grown both aerobically and anaerobically, and for each condition, both a minimal and a rich medium (minimal medium supplemented with amino acids) was used. All experiments were carried out in biological replicates using controlled bioreactor cultivations (Fig. 1B). The concentrations of biomass and key medium components, including glucose, ethanol, and amino acids, were measured, enabling precise quantification of the specific growth rate, the specific glucose uptake, the specific ethanol production rate, and uptake yields of all amino acids (Dataset S1). This analysis showed that yeast grows faster in the presence of amino acids at aerobic conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). In anaerobic conditions, growth was found to be the same from the biomass measurements, but by determining the specific growth rate from the carbon dioxide evolution rate, we found that also for anaerobic growth there was faster growth in the presence of amino acids (Dataset S1). At all four conditions, we quantified the abundance of 3,690 proteins by means of LC-MS/MS (liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry) and iBAQ (11) (Fig. 1 C and D), and found 3,074 (83%) of all quantified proteins to be present under all four conditions. The largest variation occurred between aerobic and anaerobic conditions, with 200 to 400 proteins specifically quantified to each of these two conditions (Fig. 1C).

Amino Acid Uptake Allows for Proteome Reallocation when Saccharomyces cerevisiae Is Cultivated in Rich Medium

For the cultivation of S. cerevisiae in rich medium, measurements of the extracellular concentrations of the supplemented amino acids enabled quantification of their uptake yields. The average values of their extracellular concentration, from biological triplicates, showed that nearly all of the added amino acids were taken up by the cells. Linear regression of averaged concentrations resulted in uptake yields (Fig. 2A), and this showed that glutamate had the largest uptake yield for both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Interestingly, the uptake yield of glutamate was significantly higher under anaerobic conditions compared with aerobic growth, whereas for most of the other amino acids, the uptake yield was approximately the same for the two growth conditions (Fig. 2A). Next, we investigated if the measured uptake yields (SI Appendix, Table S1) could meet the amino acid need for the proteome synthesis component of biomass formation, reported from the S. cerevisiae consensus genome-scale model, version 8.3.5 (12) (Fig. 2 B and C). In both conditions, our analysis implied a higher uptake of arginine, methionine, and threonine compared to the cellular proteomic need, whereas under anaerobic conditions, there was also an excess uptake of glutamate, indicating a catabolism of this amino acid in the central carbon metabolism.

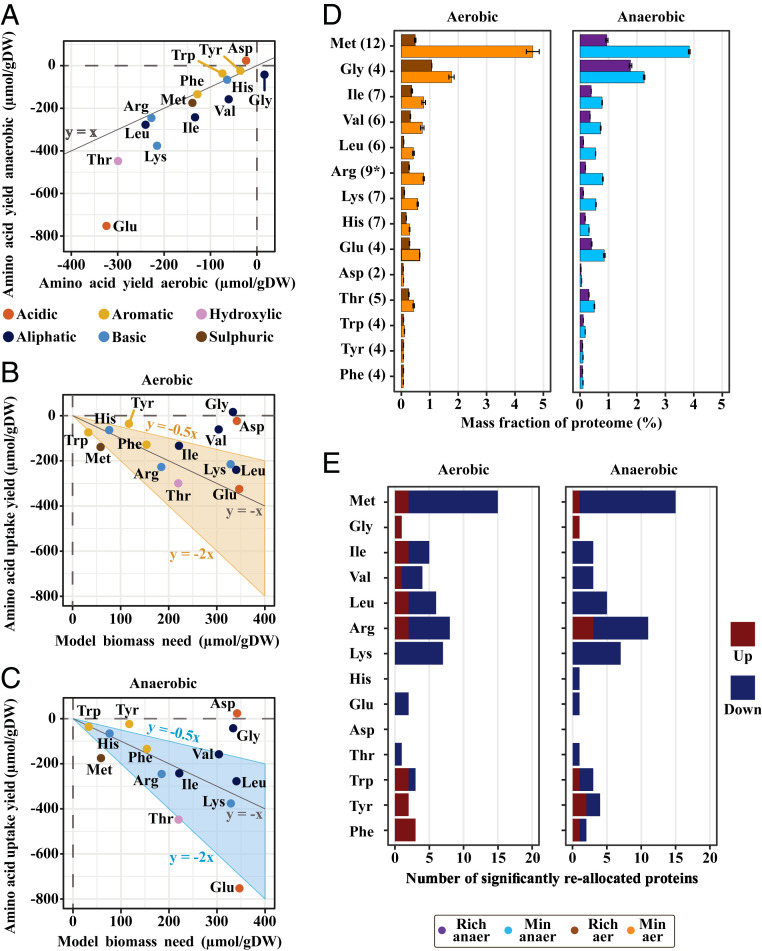

Fig. 2.

Amino acid uptake allows for proteome reallocation when S. cerevisiae is cultivated in rich medium. (A) Uptake yields (linear regression on average values of n = 3, see Dataset S1 for data and methods for description) of the supplemented amino acids plotted as a comparison between anaerobic and aerobic conditions. (B) Aerobic and (C) anaerobic uptake yields compared to estimated cellular need for the production of new biomass, reported from S. cerevisiae consensus genome scale model, version 8.3.5. (D) Mean summarized mass allocation and SD for enzymes related to biosynthesis of supplemented amino acids (based on Saccharomyces genome database biosynthetic pathways, see Dataset S1, and with number of quantified enzymes in parenthesis) in aerobic (n = 2) and anaerobic (n = 3) conditions. Of note, there are many overlapping biosynthetic enzymes between BCAAs. *In the arginine biosynthetic pathway, eight proteins were detected in aerobic cultures while nine proteins were detected in anaerobic cultures. (E) Mapping of all significantly differentially expressed proteins, up- and down-regulated, to the metabolism of the different supplemented amino acids (based on Saccharomyces genome database pathway information).

In the cases of arginine and threonine, our analysis indeed showed increased allocation of related catabolic enzymes (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3), wherein the uptake of arginine could serve as a nitrogen source and the uptake of threonine may serve as a precursor for the production of glycine and acetaldehyde. Arginine catabolism is known to be induced by cytosolic arginine, with the latter also repressing the expression of arginine synthesizing enzymes (13). Here we found two catabolic enzymes downstream of arginine, which indeed were significantly up-regulated, independent of oxygen availability (SI Appendix, Table S2). Although, under the same conditions, we found the arginine plasma membrane permease (Can1p) to be significantly down-regulated (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 C and D). A potential explanation of this could, however, be an activity-based degradation of this transporter (14). Regarding threonine catabolism, the threonine aldolase Gly1p (15) had significantly higher expression in rich medium (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), regardless of oxygen supply. This protein is also the major glycine-producing enzyme in S. cerevisiae (15), consistent with the apparent lower uptake of glycine, compared to the predicted cellular need (Fig. 2 B and C).

The excess methionine uptake was associated with a lower expression of related biosynthetic enzymes (Dataset S1). This resulted in ∼3% and 4% proteome mass saved (Fig. 2D), in rich medium, for anaerobic and aerobic cultures, respectively. This large decrease in proteome allocation may be due to the fact that an excess methionine uptake renders this pathway, used to assimilate sulfur into the methionine-precursor homocysteine, obsolete (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Also, methionine metabolism showed the largest number of significantly reallocated enzymes (Fig. 2E). The observed response was highly coordinated (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), in terms of down-regulation, corresponding to known regulation of the pathway (16). However, most of the mass was saved via the lowered allocation of the last two enzymes in the pathway, Met17p and Met6p (SI Appendix, Table S3), which were among the top 15 most abundant proteins during growth in minimal medium, independent of oxygen supply. Lowered allocation of these proteins ranged in decrease from ∼1% up to ∼2.2%.

For the branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) isoleucine, leucine, and valine and the aromatic amino acids (AAA) phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine, catabolism via the Ehrlich pathway (17) is a way for the cell to salvage nitrogen through transamination reactions. Catabolism of AAA is mediated through the activity of aromatic aminotransferase II (18) (Aro9p), while the opposite reaction, catalyzing the formation of AAA, is controlled via Aro8p under general amino acid control (GAAC). Indeed, the proteomic analysis shows a significant up-regulation of Aro9p in rich medium (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Especially for aerobic conditions there were significant changes in downstream enzymes involved in the catabolism of AAA, correlating well with the seemingly high uptake yield of tryptophan (Fig. 2 B and C).

Many enzymes engaged with the biosynthesis of BCAA had significantly lower expression in rich medium (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), with a collected decrease of ∼1.2% in both conditions (Fig. 2D), and with no significant increase in expression of enzymes related to catabolism of these amino acids. For the two branched chain amino acid transferases (Bat1p and Bat2p), that initiate the utilization pathways of BCAA, increased expression of Bat2p in aerobic cultures may have compensated for the significantly lower allocation of the major isoform, Bat1p, at glucose excess (17), in rich medium.

Lastly, the seemingly high uptake yield of glutamate during anaerobic conditions, compared to aerobic conditions, cannot be directly explained by analysis of the proteome dataset. No enzymes in its synthesis or catabolism were significantly up-regulated (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), and the significant down-regulation of the major NADP-glutamate dehydrogenase isoform (Gdh1p), during fermentative growth on glucose (19), was similar regardless of oxygen supply (SI Appendix, Table S4).

Proteomics Shows Similar Changes between Cultivation in Rich Medium for Both Aerobic and Anaerobic Conditions

Our analysis shows that similar reallocation of proteome mass fractions to different proteins between minimal and rich medium occurs independently of oxygen availability, based on the 3,074 co-occurring proteins (Fig. 1C). Proteome-wide analysis of significantly reallocated proteins showed that nine proteins had increased expression upon amino acid supplementation in both conditions (Fig. 3A). Four of these were directly related to amino acid catabolism (SI Appendix, Table S5) with the remaining related to transmembrane transport, based on yeast Gene Ontology (GO)-slim mapper process terms (20). Car1p was the most highly up-regulated enzyme, based on fold change, related to amino acid metabolism, and was significantly reallocated in both conditions (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the analysis of changes in the sum of proteome mass allocation of all significantly reallocated proteins, for aerobic and anaerobic conditions, shows that the decrease in allocation is over 10 times larger compared to increasing proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 B and C). This suggests a pattern wherein a substantial down-regulation of a few proteins is able to sustain a small increase in abundance of several others, equivalent to a proteome-constrained model (21), without altering the normal distribution of proteome allocation (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). From the 46 significantly down-regulated proteins that were identified for both conditions (Fig. 3B), 34 had GO-slim mapper process terms corresponding to cellular amino acid metabolic process, compared to the second most abundant group response to chemical, which had six proteins mapped to it. Biosynthetic enzymes related to many of the 14 supplemented amino acids were found, with one example being the aforementioned Met17p (Fig. 3D). Finally, five metabolic enzymes not directly related to amino acid metabolism, and involved in different processes, were down-regulated independently of oxygen availability (SI Appendix, Table S6), including the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)-initiating enzyme Zwf1p. In the PPP, cellular NADPH is generated, which is an important cofactor for amino acid biosynthesis (22), and the AAA precursor erythrose-4-phosphate is also formed.

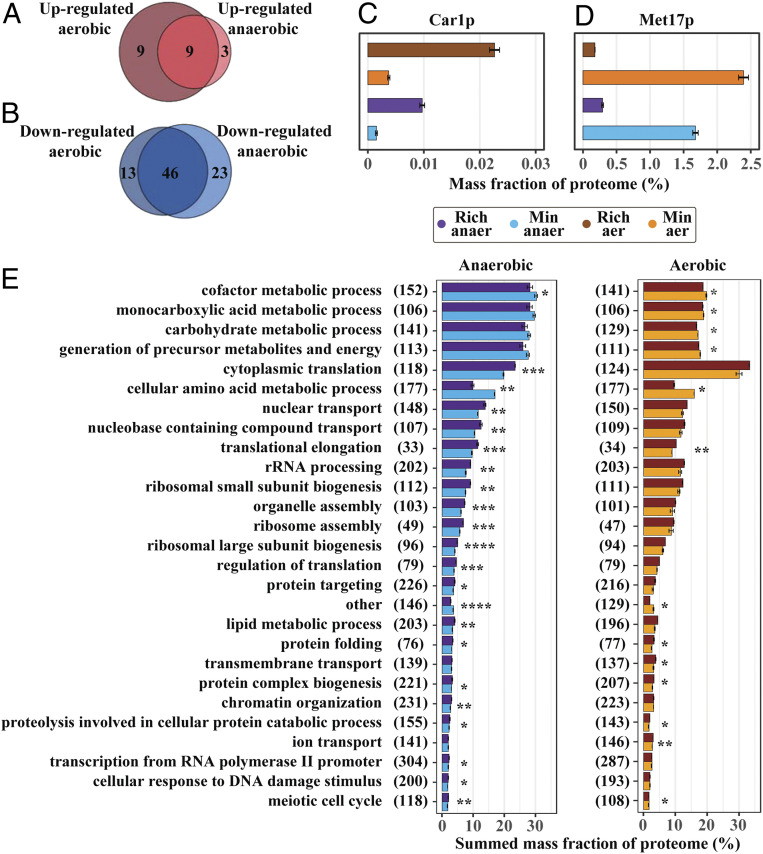

Fig. 3.

Proteomics shows similar changes between cultivation in rich medium for both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Overlap of significantly differentially expressed proteins in aerobic and anaerobic conditions for (A) up-regulated proteins and (B) down-regulated proteins. (C) Arginase (Car1p) showed one of the highest fold-changes in rich medium (n = 3 for anaerobic and n = 2 for aerobic conditions), independent of oxygen supply, and is the initiating enzyme for catalyzing arginine degradation. Mean mass allocation and SD are shown. (D) O-acetyl homoserine-O-acetyl serine sulfhydrylase (Met17p), the enzyme responsible for the penultimate step in methionine biosynthesis, showed one of the highest down-regulations (n = 3 for anaerobic and n = 2 for aerobic conditions), independent of oxygen supply, in terms of mass percentage of the proteome. Mean mass allocation and SD are shown. (E) From analysis of protein groups, based on yeast GO-slim mapper process terms (Dataset S1), average summarized mass allocation for cellular processes, with SD, were collected (n = 3 for anaerobic and n = 2 for aerobic conditions). Proteome allocation of each group were compared between rich and minimal medium, and those groups that were significantly different and with >2% summed proteome mass, in either rich or minimal medium, are highlighted. The number of summarized proteins within each process are shown in parenthesis. *P < 5e-2, **P < 1e-2, ***P < 1e-3, ****P < 1e-4.

Another similarity between aerobic and anaerobic cultivations was the significant change in proteins related to zinc deficiency for cells cultivated in rich medium. Two zinc metabolic-related membrane proteins Zrt1p and Zps1p were significantly up-regulated in both conditions in rich media (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 D and E), with Zrt1p being a high affinity zinc transporter that is necessary for growth during zinc limitation (23) and Zps1p being a cell wall protein that is induced under low-zinc conditions (20). Under the same conditions, the two alcohol dehydrogenases, Adh1p and Adh3p, both of which utilize zinc as a cofactor, showed a lower expression in rich media (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 F and G) independently of oxygen availability, which is a known strategy for S. cerevisiae to cope with zinc deficiency (23–25).

Next we analyzed changes in summed mass allocations of groups of proteins, based on the yeast GO-slim mapper process terms (Dataset S1), to acquire a holistic view on how the proteome was reallocated in response to growth in rich medium. Proteome allocation of each group was compared between rich and minimal medium, and those groups that were significantly different and with >2% summed proteome mass, in either rich or minimal medium, were investigated (Fig. 3E). The two groups that were significantly decreased in rich medium for both conditions, except the group other, were cellular amino acid metabolic process and cofactor metabolic process. In addition, the decreased allocation of the cellular amino acid metabolic process group showed the largest total change. On the other hand, the increasing processes were seen to include many groups related to translation, with cytoplasmic translation exhibiting the largest change, regardless of oxygen availability. We found similar trends when performing the analysis using previously reported groups, used for summed allocation (26), as validation (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Biological processes that related to translation, ribosomal biogenesis, or protein homeostasis (11 out of 27 groups) showed similar trends in proteome reallocation (percentual up-regulation), with for example there being a parallel increase in ribosomal small subunit biogenesis and ribosomal large subunit biogenesis, by ∼11% and 12% under aerobic conditions and by 21% and 20% in anaerobic conditions respectively. These two groups contain 115 and 99 proteins, respectively, with only 10 overlapping proteins. Taken together, this implies a well-orchestrated up-regulation of the translation machinery.

The Decreased Proteome Allocation for Amino Acid Biosynthesis Is Partly Directed toward Protein Translation

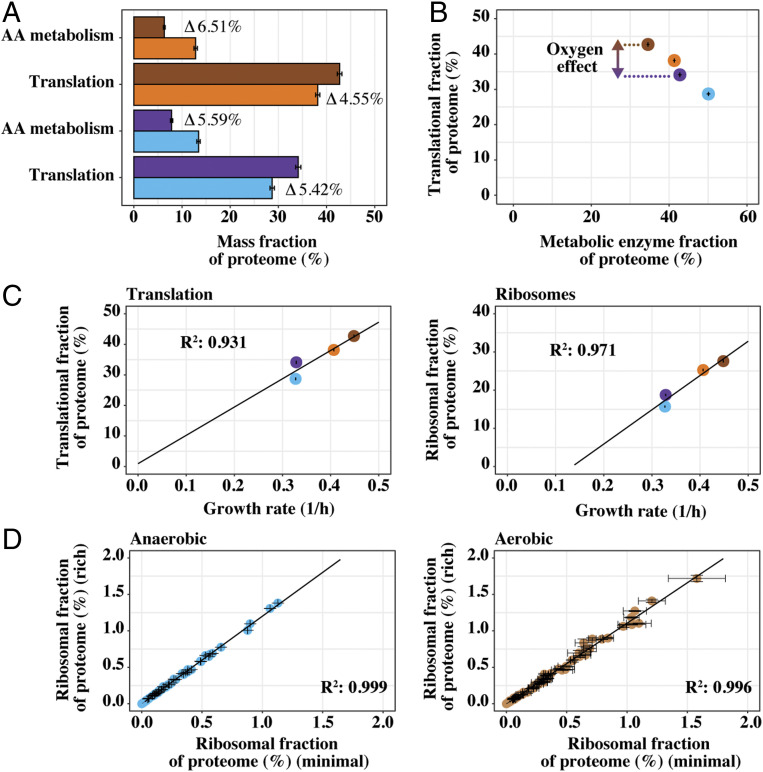

Through analysis of GO-slim mapper process terms (Dataset S1), cellular amino acid metabolic process, and cytoplasmic translation were seen to be the most highly down-regulated and up-regulated protein groups, respectively. Changes in mass allocation, between minimal and rich medium, for both these groups (Fig. 4A) were very similar, and the allocation profile for amino acid metabolism was very similar between aerobic and anaerobic conditions. We found the summed allocation of biosynthetic enzymes of the 14 supplemented amino acids (Fig. 2D), in rich medium, was 4.55% for aerobic cultivations, while it was 5.42% for anaerobic. We did see differences in allocation toward metabolic enzymes as a whole (Fig. 4B) between conditions. The increase in cytoplasmic translation, as well as ribosomal proteins (RP) which are its major constituents, was seen to correlate with increased growth rate (Fig. 4C), which is a well-known cell characteristic (3, 25–27). In addition, the allocation of individual RPs was compared between cells cultivated in rich or minimal medium (Fig. 4D), since previous work has highlighted changes in ribosomal stoichiometry (28–30) in changing growth environments. However, the analysis shows a highly consistent increase in all quantified RP subunits, including mitochondrial RP subunits (SI Appendix, Fig. S9H).

Fig. 4.

The decreased proteome allocation for amino acid biosynthesis is partly directed toward protein translation. (A) Average summed allocation, with SD, of yeast proteins in translation and amino acid (AA) metabolism, respectively. Differences in allocation, between rich and minimal medium, are highlighted for both anaerobic (n = 3) and aerobic (n = 2) conditions. (B) Average mass allocation, with SD, of translation-related proteins versus all quantified enzymes related to metabolism. (C) Summed allocation of translation and ribosomal proteins, with SD, versus growth rate (n = 3 for anaerobic and n = 2 for aerobic conditions). (D) Comparison of mean allocation, with SD, for all individual ribosomal proteins between cells cultivated in rich medium versus minimal medium (n = 3 for anaerobic and n = 2 for aerobic conditions). Proteins assigned to each group (translation, AA metabolism, ribosomes, and metabolic enzymes) were based on subsetting as performed in ref. 26. Metabolic enzymes reflected groups: AA_metabolism, Energy, Lipids, Nucleotides, Mitochondria and Glycolysis. Colors are as in Fig. 3E.

A Majority of Central Carbon Metabolic Enzymes Retain Their Allocation When Cells Are Growing at a Faster Rate in Rich Medium

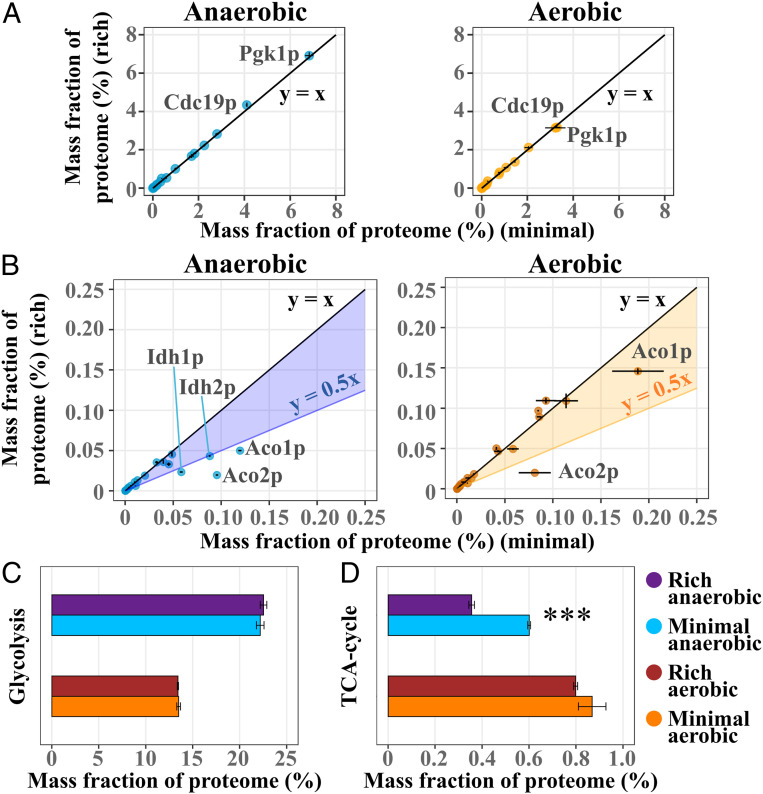

Central carbon metabolism, through its provision of biosynthetic precursors and redox cofactors, is inherently linked to amino acid biosynthesis and cell growth. We therefore analyzed protein allocation changes across glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA)-cycle to determine whether proteome changes were present, but few or no differences for individual proteins were observed, irrespective of culture medium. Specifically, in the subset of glycolytic enzymes (Dataset S1), all enzymes essentially showed the same levels irrespective of culture medium (Fig. 5A). The individual levels spread over many orders of magnitude with Pgk1p and Cdc19p showing the highest levels of allocation, independent of oxygen availability. In general, no significant difference was seen in the sum of mass allocation for glycolytic enzymes between cells cultivated in rich or minimal medium (Fig. 5C), nor was any significant difference in specific ethanol production observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). A lower specific glucose uptake rate was seen in anaerobic conditions, which correlated with a lower glycerol production rate. For enzymes related to the TCA-cycle (Dataset S1) (Fig. 5B), however, we saw lower allocation levels for Aco1p, Aco2p, Idh1p, and Idh2p in rich medium (SI Appendix, Table S7). All of these four enzymes, which are responsible for a two-step oxidation of citrate into α-ketoglutarate, were seen to be significantly down-regulated in rich medium for anaerobic cultures. During aerobic conditions, Aco2p in particular showed substantial down-regulation in rich medium (log2(FC) of −2.04) as well. Reduced aconitase activity has previously been coupled to the presence of glucose, and even more so upon addition of glutamate (31), consistent with high glutamate uptake rates in both conditions (Fig. 2A). However, no concomitant significant up-regulation of Gdh2p, the enzyme responsible for glutamate conversion into 2-oxoglutarate, was seen. The decreased allocation of the NAD(+)-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase complex (Idh1p and Idh2p), a crucial part of the TCA-cycle (32), could imply a reduced need for metabolic flux through the oxidative branch of the TCA-cycle (33) upon amino acid supplementation in anaerobic cultures. Overall, there was a significant decrease in summed protein allocation toward enzymes of the TCA-cycle for anaerobically cultured cells in rich medium (Fig. 5D), mainly through reduced allocation for the aforementioned enzymes with the highest abundances.

Fig. 5.

A majority of central carbon metabolic enzymes retain their allocation when cells are growing at a faster rate in rich medium. (A) Comparison of average summed allocation, with SD, of quantified enzymes in glycolysis between cells cultivated in rich medium versus minimal medium (n = 3 for anaerobic and n = 2 for aerobic conditions). Highlighting the two most abundant enzymes. (B) Comparison of average summed allocation, with SD, of quantified enzymes in the TCA-cycle between cells cultivated in rich medium versus minimal medium (n = 3 for anaerobic and n = 2 for aerobic conditions). Highlighting significantly down-regulated enzymes and Aco1p, which showed the highest abundance. (C) Average summed allocation, with SD, of enzymes in glycolysis, based on Saccharomyces genome database pathway, see Dataset S1 (n = 3 for anaerobic and n = 2 for aerobic conditions). (D) Average summed allocation, with SD, of enzymes in the TCA-cycle, based on Saccharomyces genome database pathway, see SI Appendix (n = 3 for anaerobic and n = 2 for aerobic conditions. ***P < 1e-3.

Discussion

Cellular limitations in proteome size and its necessary allocation trade-offs have been addressed both in silico (4, 8) and in vivo (3, 25, 26). With this work, we empirically investigated proteome reallocation by perturbing cellular metabolism through amino acid supplementation and analyzed changes in the context of increased growth rate and biomass yield (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Most amino acids were taken up solely for protein synthesis (Fig. 2 B and C) resulting in a massive down-regulation of amino acid biosynthetic enzymes (Fig. 2 D and E). This was particularly true for methionine biosynthesis. Based on the number of enzymes involved, but also on enzyme weights and turnover numbers (9, 34) in amino acid metabolism (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A and B), it makes sense economically for the cells to have a low methionine biosynthesis through high methionine uptake, and also because the sulfur in this amino acid can be incorporated into cysteine. Furthermore, methionine has been shown to impact oxidative stress resistance (35) and has the potential to be catabolized into α-ketoglutarate (36), which can directly enter central carbon metabolism, providing additional support for why the demand for cell uptake was high. Glutamate, the most abundant supplemented amino acid (SI Appendix, Fig. S12A), showed the highest uptake yield, and although no directly linked catabolic enzymes were significantly up-allocated (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) glutamate may be utilized metabolically for other transamination reactions, as it is the major amino acid for this role (13). Moreover, its important role in oxidative stress response (37) via the gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA)-shunt also did not show any significantly changed expression. The allocation per protein in glutamate biosynthesis decreased substantially (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 C and D) upon amino acid supplementation. Finally, glycine was also found to have a high allocation per protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S12A), but low uptake when it was supplemented. Uptake of glycine could possibly be achieved through the Dip5p transporter (38), which was significantly up-regulated upon supplementation in aerobic cultures (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). However, this would be in competition with glutamate uptake; therefore, glycine is likely synthesized from the breakdown of threonine via the significantly up-regulated Gly1p (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Such glycine production could also be an example of justified cellular proteomic investment in catabolism of amino acids, since another abundant enzyme Shm2p showed down-regulation (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), particularly in anaerobic conditions.

From validation of our dataset through comparison to previously reported allocation groups (26) (SI Appendix, Fig. S10), we saw good consistency for cells cultivated aerobically. From anaerobic samples, the condition more than the growth rate seemed to affect the mitochondrial allocation, highlighting that culture condition differences have to be taken into account for proteome allocation analyses. However, this does not impact our study as we focus on changes from minimal to rich medium within the same conditions, i.e., aerobic or anaerobic growth.

For aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions, a consistent ratio between reallocation of protein mass from cellular amino acid biosynthesis to cytoplasmic translation was observed. Approximately half (42% in anaerobic conditions and 51% in aerobic conditions) of the proteome mass saved by supplementing amino acids in the medium was redirected toward proteins engaged in translation (Fig. 4A). Besides this, in rich medium, proteome mass was also redirected to several other processes related to translation (Fig. 3E). With not many other metabolic enzymes or pathways being up-regulated, including glycolysis and the TCA-cycle (Fig. 5), and with ethanol secretion rate not being significantly different (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), these data imply that a relief in proteomic constraint is driving the increase in growth rate. Although altered nutrient supply is indeed related to transfer RNA (tRNA)-aminoacylation levels, GAAC (13), and potential regulatory effects through the target of rapamycin (TOR) Ser/Thr kinase (39), by enabling more proteome allocation for the ribosomes this may additionally relieve a potential limiting factor on growth rate.

In conclusion, our study provides experimental validation, at two different metabolic conditions, to the proteomic resource allocation model. This supports the idea that lean proteomic strains could be pursued as a strategy to design efficient cell factory platform strains that harbor large heterologous biosynthetic pathways.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Culture Conditions.

The yeast S. cerevisiae CEN.PK113-7D (MATa, MAL2-8c, SUC2) was used for all experiments. All batch cultures were carried out in DASGIP 1 L bioreactors with off-gas analysis, pH-control, temperature-control, and sensors for dissolved oxygen in culture medium. Fixed parameters for all cultures were 30 °C and a pH of 5, which was controlled through automatic addition of 2 M KOH or 2 M HCl, as well as starting inoculum optical density of 0.1.

For aerobic cultures, a working volume of 0.7 L, 1 vvm aeration with 21% O2, and agitation of 800 rpm was used. For anaerobic cultures, a working volume of 1.0 L, 20 L/h aeration with 0% O2 (pure N2), and agitation of 400 rpm was used. The basis of all cultures was a minimal medium that contained 20 g/L glucose, 5 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 3 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 1 mL/L trace metal solution, 1 mL/L vitamin solution, and 0.1 mL/L antifoam 204 (Sigma-Aldrich, ). The trace metal solution consisted of 19 g/L Na2EDTA⋅2H2O (disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate dihydrate), 4.5 g/L ZnSO4⋅7H2O, 1 g/L MnCl2⋅4H2O, 0.3 g/L CoCl2⋅6H2O, 0.3 g/L CuSO4⋅5H2O, 0.4 g/L Na2MoO4⋅2H2O, 4.5 g/L CaCl2⋅2H2O, 3 g/L FeSO4⋅7H2O, 1 g/L H3BO3 and 0.1 g/L potassium iodide. The vitamin solution consisted of; 0.05 g/L d-Biotin, 0.2 g/L 4-aminobenzoic acid, 1g/L nicotinic acid, 1 g/L D-Pantothenic acid hemicalcium salt, 1 g/L pyridoxine-HCl, 1 g/L thiamine-HCl, 25 g/L and myo-inositol. The rich medium used was the same as the minimal medium, with the addition of the following amino acids: 0.19 g/L l-arginine; 0.4 g/L l-aspartate; 1.26 g/L l-glutamate; 0.13 g/L l-glycine; 0.14 g/L l-histidine; 0.29 g/L l-isoleucine; 0.4 g/L l-leucine; 0.44 g/L l-lysine; 0.108 g/L l-methionine; 0.2 g/L l-phenylalanine; 0.22 g/L l-threonine; 0.04 g/L l-tryptophan; 0.052 g/L l-tyrosine; 0.38 g/L l-valine. Both rich and minimal medium that was used for anaerobic conditions additionally contained 0.0104 g/L ergosterol and 0.42 g/L Tween80 that had been dissolved in pure ethanol. Subsequently, medium used for anaerobic conditions contained 2.85 g/L ethanol.

Sampling from Bioreactor.

For all sampling timepoints, the dead-volume of the sampling port was removed prior to sampling. For proteomics, samples were centrifuged for 3 to 5 min at 3,000 × g below 0 °C; cell pellets were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Determination of dry cell weight concentration was started by vacuum filtration of samples on preweighed 0.45 µm filter membranes (Sartorius Biolab) followed by microwaving of filters at 125 to 325 W for 15 min and placement in a desiccator for at least 3 d. The weight increase was later determined and normalized into gDW/L. Sampling for analysis of metabolites in extracellular medium was performed by filtration of samples, with 0.45 µm filters, and storage of cell-free culture liquid at −20 °C, until analysis.

Exometabolic Analysis.

Extracellular glucose, ethanol, glycerol, pyruvate, and acetate were quantified by HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography; ultimate 3000 HPLC, Thermo Fisher) with a BioRad HPX-87H column (BioRad) and an infrared detector. The elution buffer used was 5 mM H2SO4, and all operated at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min with an oven temperature of 45 °C.

Analysis of Amino Acid Uptake.

Ten microliters of 10% sulfosalicylic acid containing 400 μmol/L norleucine was added to 40 μL of sample extracts that were prediluted 1:1 with MQ water. Samples were then vortex mixed and centrifuged, and 10 μL of supernatant was mixed with 40 μL labeling buffer containing norvaline. Ten microliters of the supernatant was recovered and 5 μL of diluted aTRAQ Δ8-reagent was added, and the mixture was mixed and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Thereafter, 5 μL of hydroxylamine was added and the mixture was incubated for another 15 min at room temperature. Thirty-two microliters of reconstituted aTRAQ Internal Standard solution and 400 μL of water was added to the reaction mixture followed by mixing and transferring into vials for analysis by UHPLC-MS/MS (ultraperformance LC-MS/MS). Samples were analyzed by using a Sciex QTRAP 6500+ system (AB Sciex) with a Nexera UHPLC system (Shimadzu). One microliter of sample was separated on an AB Sciex AAA column (150 × 4.6 mm) held at 50 °C by using gradient elution (SI Appendix, Table S8) with water and methanol, both containing 0.1% formic and 0.01% heptafluorobutyric acids, as mobile phases (total flow 0.8 mL/min). The mass spectrometer was set to monitor the transitions (SI Appendix, Table S9) with the following ion source parameters: curtain gas 30, collision activated dissociation medium, ionization voltage 5500, temperature 500, GS1 (source gas 1) 60, and GS2 50 and compound parameters: declustering potential 30, entrance potential 10, collision energy 30, and collision cell exit potential 5. Samples from aerobic fermentation and anaerobic fermentation experiments were run in two independent batches. For quantification, an external standard curve of pure amino acid solution, matching amino acid supplement, was constructed for four to five different concentrations. The signal from the external standard was compared to that of the internal standard and its correlation to the expected concentrations of the external standard was used as a basis for deducting concentrations of amino acids in collected samples of extracellular medium. From each sample timepoint, amino acid concentrations that passed manual QC (quality control) and biomass concentrations were averaged, and through linear regression of averaged data points uptake yields were obtained. The detailed amino acid uptake analyses are described in the SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods section.

Quantitative Proteome Analysis.

All liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) experiments were performed on an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer interfaced with an Easy-nLC1200 nanoflow liquid chromatography system (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The global relative protein quantification between the samples was performed via the modified filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) method (40), which included the two-stage digestion of each sample with trypsin in 1% sodium deoxycholate (SDC)/50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) buffer and labeling with the TMT (tandem mass tag) 11plex isobaric reagents (Thermo Fischer Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The pooled reference sample was prepared from the aliquots of the lysates of S. cerevisiae CEN.PK 113–7D cells from the J. Nielsen Lab (Chalmers). The combined TMT-labeled set was prefractionated into 20 final fractions on an XBridge BEH C18 column (3.5 μm, 3.0 × 150 mm; Waters Corporation) at pH 10, and each fraction was analyzed using a 60 or 90 min LC-MS method. The most abundant peptide precursors were selected in a data-dependent manner, collision-induced dissociation (CID) MS2 spectra for peptide identification were recorded in the ion trap, the five or seven most abundant fragment ions were isolated via the synchronous precursor selection (SPS), fragmented using the higher-energy collision dissociation (HCD), and the MS3 spectra for reporter ion quantification were recorded in the Orbitrap.

Peptide and protein identification and quantification were performed using Proteome Discoverer version 2.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with Mascot 2.5.1 (Matrix Science) as a database search engine. The baker’s yeast (S. cerevisiae ATCC 204508/S288c) reference proteome database from UniProt (February 2018, 6,049 sequences) and used for the database search on the TMT-based relative quantification files; the concatenated database containing the yeast sequences and the 48 ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) protein sequences was used for the processing of the UPS2-spiked data. The TMT reporter ions were identified in the MS3 HCD spectra with a mass tolerance of 3 milli mass units (mmu). The resulting reporter abundance values for each sample were normalized within Proteome Discoverer 2.2 on the total peptide amount. After manual QC, one replicate from minimal aerobic and one replicate from rich aerobic were removed from downstream proteomics analysis. Within each sample, the variability of the abundance of individual peptides for each protein was quite high, and the source of this is unknown. However, each peptide agreed very well in terms of their relative abundance between samples; therefore, the relative abundance of proteins, reported in Dataset S1, is of high confidence.

The intensity-based absolute quantification (iBAQ) approach (11) was used to estimate the absolute protein concentrations in the pooled reference sample. An aliquot of 50 µg of the pooled sample was spiked with 10.6 µg of the UPS2 Proteomics Dynamic Range Standard (Sigma-Aldrich) and digested using the FASP protocol, prefractionated at pH 10 on the XBridge BEH C18 column (3.5 μm, 3.0 × 150 mm) into 10 fractions, and each fraction was analyzed 3 times using a 90 min method with MS1 spectra recorded at 120,000 resolution, and the data-dependent CID MS2 spectra recorded in the ion trap with 1s duty cycle. The label-free data were processed using the Minora feature detection node in Proteome Discoverer version 2.2, and the quantitative values from three technical (injection) replicates were averaged. Forty-three proteins from the UPS2 standard were detected with two or more unique peptides and used to calculate the linear regression coefficients between the known concentrations of the UPS2 proteins and their corresponding iBAQ measurements. The slope and y-intercept of the linear regression were used to quantify the yeast proteins in the pooled reference sample. The adjusted R2 of the linear model was 0.95, P = 2.2e-16. The absolute concentration estimates were calculated for each of the eight samples using the iBAQ-based absolute values for the pooled reference sample and the relative abundance values from the TMT experiment.

The detailed experimental procedures, LC-MS, and data processing parameters are described in the SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods section.

Analysis of Proteome-Allocation for Individual Proteins.

Identified proteins with two or more peptide spectrum matches, with a sample to reference TMT ratio between 0.1 and 10 in biological replicates of either aerobic or anaerobic conditions, were included in downstream analyses. Proteins were quantified individually in the group of their respective condition (rich or minimal medium during aerobic or anaerobic conditions) by normalizing all proteins against total measured protein abundancies, after criteria cutoff. Leading to each protein being represented as a percentage of the proteome, within that biological replicate, and with the sum of all proteins adding up to 1. This was done by multiplying relative ratio with determined amount in the reference and converting to grams of protein A per microgram of total protein in sample, by molecular weight, and finally dividing by the sum of all proteins. Through this analysis, every protein abundance was expressed as a percentage of the entire proteomic mass.

For GO-slim mapper process terms analysis, all proteins in all datasets were merged and the terms had matching proteins annotated to them (Dataset S1; accessed March 2019), or analyzed by the Saccharomyces Genome Database Gene Ontology Slim Term Mapper online tool (accessed May 2020). For summation of allocation, each individual dataset was subsequently matched to the set-up GO-slim mapper process term framework, to identify which proteins to be summed.

Statistical Analysis.

Determination of statistically significant differences between protein allocations from rich medium datasets and minimal medium datasets were made from log2-transformed values with unpaired two-sided Student’s t test. Unless otherwise stated, significantly reallocated proteins are proteins with a log2(fold change) greater than 1 or less than -1, and with a false discovery rate < 0.05 for the anaerobic dataset, or a P value < 0.05 for the aerobic dataset (41). Significant changes in protein abundance were always compared between cells cultivated in rich medium versus minimal medium, and never between aerobic versus anaerobic conditions.

Data and Code Availability.

Processed quantitative proteomics data and quantified cellular uptake and excretion rates of metabolites, including supplemented amino acids, can be found in the Dataset S1. Proteomics mass spectrometry data were deposited into the ProteomeXchange Consortium, via the PRIDE (42) partner repository, with dataset identifiers PXD012803 for iBAQ (43) and PXD018361 for TMT-based relative quantification (44). Custom scripts and related data used for analysis are freely available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/SysBioChalmers/ProteomeReallocationForFastGrowth).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Carina Sihlbom, Egor Vorontsov, and the Proteomics Core Facility at Sahlgrenska Academy of the University of Gothenburg for help with obtaining the proteomic data, advice, and useful discussions and comments. We also thank Otto Savolainen and Chalmers Mass Spectrometry Infrastructure of Chalmers University of Technology for helpful discussions, guidance, and advice on analyzing amino acids. This work was funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Grant NNF10CC1016517).

Footnotes

Competing interest statement: J.N. is the CEO of the BioInnovation Institute, Denmark.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1921890117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kuhn K. M., DeRisi J. L., Brown P. O., Sarnow P., Global and specific translational regulation in the genomic response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to a rapid transfer from a fermentable to a nonfermentable carbon source. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 916–927 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godard P. et al., Effect of 21 different nitrogen sources on global gene expression in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 3065–3086 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott M., Hwa T., Bacterial growth laws and their applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 22, 559–565 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basan M. et al., Overflow metabolism in Escherichia coli results from efficient proteome allocation. Nature 528, 99–104 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghaemmaghami S. et al., Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature 425, 737–741 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valgepea K., Peebo K., Adamberg K., Vilu R., Lean-proteome strains–Next step in metabolic engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 3, 11 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien E. J., Utrilla J., Palsson B. O., Quantification and classification of E. coli proteome utilization and unused protein costs across environments. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1004998 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilsson A., Nielsen J., Metabolic trade-offs in yeast are caused by F1F0-ATP synthase. Sci. Rep. 6, 22264 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sánchez B. J. et al., Improving the phenotype predictions of a yeast genome-scale metabolic model by incorporating enzymatic constraints. Mol. Syst. Biol. 13, 935 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang M. et al., Microfluidic screening and whole-genome sequencing identifies mutations associated with improved protein secretion by yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E4689–E4696 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwanhäusser B. et al., Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473, 337–342 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu H. et al., A consensus S. cerevisiae metabolic model Yeast8 and its ecosystem for comprehensively probing cellular metabolism. Nat. Commun. 10, 3586 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ljungdahl P. O., Daignan-Fornier B., Regulation of amino acid, nucleotide, and phosphate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 190, 885–929 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gournas C., Prévost M., Krammer E. M., André B., “Function and regulation of fungal amino acid transporters: Insights from predicted structure” in Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Ramos J., Sychrová H., Kschischo M., Eds. (Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2016), pp. 69–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monschau N., Stahmann K. P., Sahm H., McNeil J. B., Bognar A. L., Identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae GLY1 as a threonine aldolase: A key enzyme in glycine biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 150, 55–60 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas D., Surdin-Kerjan Y., Metabolism of sulfur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61, 503–532 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazelwood L. A., Daran J.-M. G., van Maris A. J. A., Pronk J. T., Dickinson J. R., The Ehrlich pathway for fusel alcohol production: A century of research on Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2259–2266 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iraqui I., Vissers S., Cartiaux M., Urrestarazu A., Characterisation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ARO8 and ARO9 genes encoding aromatic aminotransferases I and II reveals a new aminotransferase subfamily. Mol. Gen. Genet. 257, 238–248 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeLuna A., Avendaño A., Riego L., González A., NADP-glutamate dehydrogenase isoenzymes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Purification, kinetic properties, and physiological roles. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43775–43783 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherry J. M. et al., Saccharomyces genome database: The genomics resource of budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D700–D705 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snoep J. L., Yomano L. P., Westerhoff H. V., Ingram L. O., Protein burden in Zymomonas mobilis: Negative flux and growth control due to overproduction of glycolytic enzymes. Microbiology 141, 2329–2337 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albers E., Larsson C., Lidén G., Niklasson C., Gustafsson L., Influence of the nitrogen source on Saccharomyces cerevisiae anaerobic growth and product formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 3187–3195 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao H., Eide D., The yeast ZRT1 gene encodes the zinc transporter protein of a high-affinity uptake system induced by zinc limitation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 2454–2458 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.North M. et al., Genome-wide functional profiling identifies genes and processes important for zinc-limited growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002699 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eide D. J., Homeostatic and adaptive responses to zinc deficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 18565–18569 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metzl-Raz E. et al., Principles of cellular resource allocation revealed by condition-dependent proteome profiling. eLife 6, 1–22 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott M., Gunderson C. W., Mateescu E. M., Zhang Z., Hwa T., Interdependence of cell growth and gene expression: Origins and consequences. Science 330, 1099–1102 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosdriesz E., Molenaar D., Teusink B., Bruggeman F. J., How fast-growing bacteria robustly tune their ribosome concentration to approximate growth-rate maximization. FEBS J. 282, 2029–2044 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samir P. et al., Identification of changing ribosome protein compositions using mass spectrometry. Proteomics 18, e1800217 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slavov N., Semrau S., Airoldi E., Budnik B., van Oudenaarden A., Differential stoichiometry among Core ribosomal proteins. Cell Rep. 13, 865–873 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gangloff S. P., Marguet D., Lauquin G. J., Molecular cloning of the yeast mitochondrial aconitase gene (ACO1) and evidence of a synergistic regulation of expression by glucose plus glutamate. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 3551–3561 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keys D. A., McAlister-Henn L., Subunit structure, expression, and function of NAD(H)-specific isocitrate dehydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 172, 4280–4287 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Camarasa C., Grivet J. P., Dequin S., Investigation by 13C-NMR and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) deletion mutant analysis of pathways for succinate formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae during anaerobic fermentation. Microbiology 149, 2669–2678 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Apweiler R. et al., UniProt: The Universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D115–D119 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell K., Vowinckel J., Keller M. A., Ralser M., Methionine metabolism alters oxidative stress resistance via the pentose phosphate pathway. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 24, 543–547 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perpète P. et al., Methionine catabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 6, 48–56 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman S. T., Fang T. K., Rovinsky S. A., Turano F. J., Moye-Rowley W. S., Expression of a glutamate decarboxylase homologue is required for normal oxidative stress tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 244–250 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bianchi F., Van’t Klooster J. S., Ruiz S. J., Poolman B., Regulation of amino acid transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 83, 1–38 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M. N., TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124, 471–484 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiśniewski J. R., Zougman A., Nagaraj N., Mann M., Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods 6, 359–362 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pascovici D., Handler D. C., Wu J. X., Haynes P. A., Multiple testing corrections in quantitative proteomics: A useful but blunt tool. Proteomics 16, 2448–2453 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez-Riverol Y. et al., The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: Improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D442–D450 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vorontsov E., Nielsen J., Data from “Label-free quantification of yeast cellular proteome." PRIDE. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD012803. Accessed 12 August 2020.

- 44.Nielsen J.; Proteomics Core Facility, SAMBIO Core Facilities, Data from “Proteome re-allocation in amino acid supplemented S. cerevisiae using TMT-based quantitative proteomics.” PRIDE. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD018361. Accessed 12 August 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Processed quantitative proteomics data and quantified cellular uptake and excretion rates of metabolites, including supplemented amino acids, can be found in the Dataset S1. Proteomics mass spectrometry data were deposited into the ProteomeXchange Consortium, via the PRIDE (42) partner repository, with dataset identifiers PXD012803 for iBAQ (43) and PXD018361 for TMT-based relative quantification (44). Custom scripts and related data used for analysis are freely available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/SysBioChalmers/ProteomeReallocationForFastGrowth).