Significance

Control of the level of calcium inside mitochondria is important because mitochondrial calcium regulates metabolism, cell death, and cellular signaling. The main pathway for mitochondrial calcium uptake is a calcium-selective ion channel complex in the inner mitochondrial membrane called the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU). How the activity of the MCU ion channel is regulated is controversial. Here we employed electrophysiology of single isolated mitochondria to record MCU calcium and sodium ionic currents. We found that MCU ion channel activity is controlled by distinct Ca2+-regulated mechanisms on both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane that are coupled to each other. These mechanisms allow for enhanced cellular regulation of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis.

Keywords: mitochondria, electrophysiology, calcium, MICU1, EMRE

Abstract

Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria regulates bioenergetics, apoptosis, and Ca2+ signaling. The primary pathway for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), a Ca2+-selective ion channel in the inner mitochondrial membrane. MCU-mediated Ca2+ uptake is driven by the sizable inner-membrane potential generated by the electron-transport chain. Despite the large thermodynamic driving force, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is tightly regulated to maintain low matrix [Ca2+] and prevent opening of the permeability transition pore and cell death, while meeting dynamic cellular energy demands. How this is accomplished is controversial. Here we define a regulatory mechanism of MCU-channel activity in which cytoplasmic Ca2+ regulation of intermembrane space-localized MICU1/2 is controlled by Ca2+-regulatory mechanisms localized across the membrane in the mitochondrial matrix. Ca2+ that permeates through the channel pore regulates Ca2+ affinities of coupled inhibitory and activating sensors in the matrix. Ca2+ binding to the inhibitory sensor within the MCU amino terminus closes the channel despite Ca2+ binding to MICU1/2. Conversely, disruption of the interaction of MICU1/2 with the MCU complex disables matrix Ca2+ regulation of channel activity. Our results demonstrate how Ca2+ influx into mitochondria is tuned by coupled Ca2+-regulatory mechanisms on both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane.

The mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) is a Ca2+-selective ion channel in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) (1) that represents the major mechanism by which mitochondria take up Ca2+ into the matrix to regulate bioenergetics, cell death pathways, and cytoplasmic Ca2+ signaling. MCU-mediated Ca2+ uptake is driven by the large (−150 to −180 mV) inner-membrane voltage (ΔΨm) generated by proton pumping into the intermembrane space (IMS) by the electron-transport chain during oxidative phosphorylation. Despite the considerable driving force for Ca2+ entry into the mitochondrial matrix, mitochondrial matrix free [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]m) at rest is maintained at ∼100 nM, similar to the resting cytoplasmic free [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i). Whereas transient elevations of [Ca2+]m promote enhanced adenosine 5′-triphosphate production to support cellular energy demands, failure to maintain low matrix [Ca2+] may trigger ΔΨm dissipation and opening of the permeability transition pore (PTP) that can result in cell death. Thus, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake must be tightly controlled, but how mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake through MCU is regulated is controversial (2–4). In metazoans, the MCU channel exists as a protein complex composed of MCU as the tetrameric channel pore-forming subunit (5, 6), EMRE, a single-pass transmembrane protein that is essential for channel activity (7–9), and IMS-localized (but see ref. 10) Ca2+-binding EF hand domain-containing MICU1/2 heterodimers (11–14) that associate with the channel complex by interactions with the carboxyl terminus of EMRE (15) and with MCU (16, 17). Despite early controversies regarding the location of MICU proteins and the nature of the MICU-dependent regulation (see ref. 4), in the most widely accepted current model of MCU regulation by MICU proteins (but see refs. 2 and 4), MICU1/2 promotes cooperative channel activation in response to Ca2+ binding by their EF hands, whereas apo-MICU1/2 imposes a threshold [Ca2+]i below which MCU channel activity is inhibited, so-called channel gatekeeping (14, 15, 18–25).

Two fundamental observations suggest that this model of MCU regulation is inadequate. First, it cannot account for the observation that the channel can be open with the MICU1/2 EF hands in their apo state under experimental conditions in which [Ca2+]i is reduced to low levels that permit Na+ permeation (1, 26, 27). Second, by mitoplast electrophysiology of the IMM with pipette solutions containing defined free [Ca2+], we previously reported that matrix [Ca2+] also regulates MCU-channel gating, with strong inhibition at normal resting [Ca2+]m and maximal channel inhibition ∼80% at ∼400 nM (27). In this condition, the channel was strongly inhibited by MICU1/2 despite their being fully Ca2+-liganded by Ca2+ present in the bathing solution, an observation that also cannot be accounted for by the current model of MCU regulation.

Here we set out to understand the matrix [Ca2+] regulation of MCU-channel activity and the mechanisms that regulate Na+ permeation. By varying mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering capacity and [Ca2+]m in mitoplast patch-clamp electrophysiology experiments, we determined that Ca2+ that permeates through the channel pore regulates Ca2+ affinities of coupled inhibitory and activating sensors in the matrix. We localized the inhibitory sensor within the MCU amino terminus which, upon binding Ca2+, inhibits channel activity despite Ca2+ binding to MICU1/2. Disruption of this inhibitory Ca2+-binding site significantly promoted PTP opening in intact mitochondria in response to Ca2+ additions. Conversely, disruption of the interaction of MICU1/2 with the MCU complex abolished matrix Ca2+ regulation of channel activity. A model of coupled transmembrane Ca2+-regulatory mechanisms was developed to account for these data, including the observation that the channel can be open with the MICU1/2 EF hands in their apo state under conditions in which Na+ is the permeant ion (1, 26, 27).

Results

Matrix [Ca2+] Regulation of MCU Ca2+-Channel Activity.

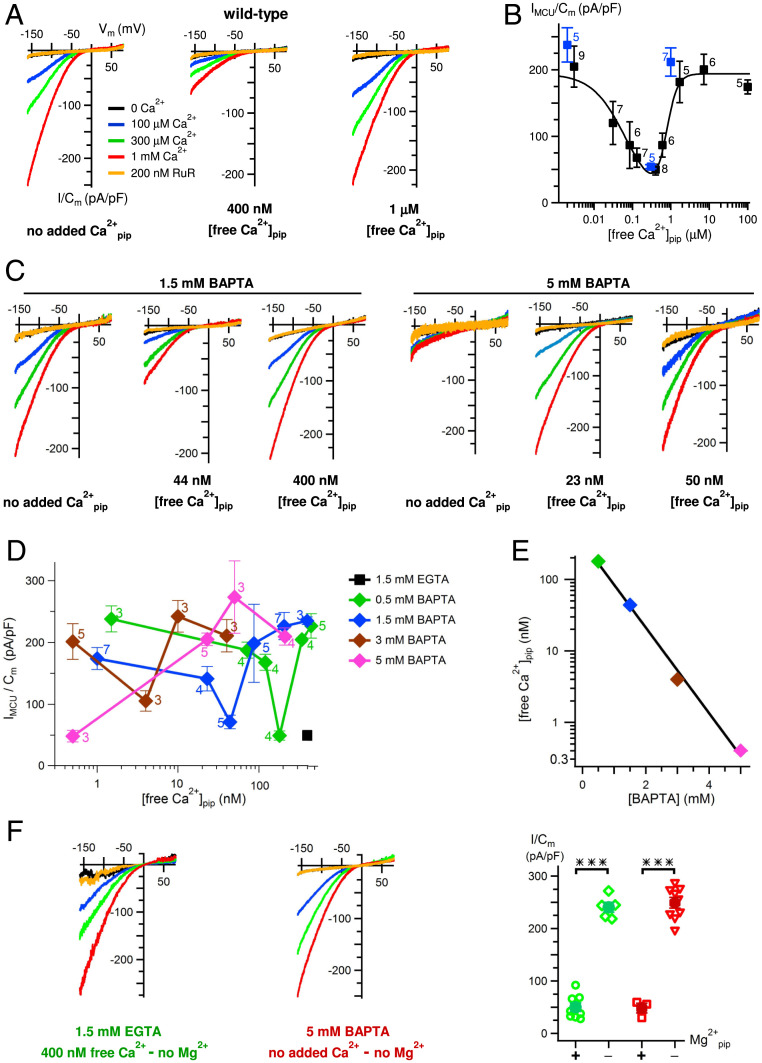

We previously determined that matrix [Ca2+] regulated MCU-channel activity with a biphasic concentration dependence, with strong inhibition at normal resting [Ca2+]m (∼100 nM) and maximal channel inhibition ∼80% at ∼400 nM (27). We first confirmed this matrix [Ca2+] regulation by recording MCU Ca2+ currents in mitoplasts isolated from HEK293 cells, with the patch-clamp pipette solution that filled the mitochondrial matrix containing defined [Ca2+] buffered with 1.5 mM EGTA. Ca2+ currents were large with pipette solutions containing 1.5 mM EGTA with either no added Ca2+ or with free [Ca2+] set to 1 μM, whereas they were inhibited by ∼80% at 400 nM Ca2+, in excellent agreement with the previous observations (Fig. 1 A and B). This regulation occurred while MICU1/2 was in its Ca2+-liganded state due to the presence of high bath [Ca2+] necessary to record MCU Ca2+ currents. Accordingly, in the simplest model to account for MCU channel regulation, the channel complex possesses two matrix-localized Ca2+-sensing sites, inhibitory (Si) and activating (Sa), whose Ca2+ occupancies control the functionality of MICU1/2 on the other side of the membrane to regulate channel gating.

Fig. 1.

MCU activity is regulated by matrix [Ca2+]. (A) Representative families of MCU Ca2+ currents, normalized to mitoplast capacitance, in response to voltage ramps in wild-type mitoplasts, with pipette free [Ca2+] in 1.5 mM EGTA indicated under each panel. Colors denoting bath conditions are used throughout. (B) Biphasic matrix [Ca2+] regulation of MCU Ca2+-current density in wild-type mitoplasts at −160 mV with 1 mM bath [Ca2+]. Data from the current study shown in blue. Data from ref. 27 shown in light gray for reference. Peak inhibition is observed with matrix free [Ca2+] = 400 nM. Numbers indicate number of mitoplast recordings. Bars denote SEM. (C) Representative MCU Ca2+ currents with different pipette free [Ca2+] (shown below each set of traces) buffered with either 1.5 mM BAPTA (left group of three panels) or 5 mM BAPTA (right group of three panels). Normal inhibition with matrix free [Ca2+] = 400 nM buffered with 1.5 mM EGTA is shifted to 10-fold lower concentration in presence of 1.5 mM BAPTA (center in the left group). In 5 mM BAPTA, inhibition is shifted further to lower matrix free [Ca2+] (left in the right group). (D) MCU Ca2+-current density over range of pipette free [Ca2+] and buffering capacity. Black symbol marks the minimum reported in B. Numbers indicate numbers of mitoplasts recorded. Biphasic dependence of Ca2+-current density on matrix free [Ca2+] is shifted to lower concentrations with stronger buffering. (E) Relationship between the maximally inhibited MCU Ca2+-current density recorded [from (D)] as a function of pipette [BAPTA]. (F) Inhibition of MCU activity observed with matrix Ca2+ = 400 nM buffered with 1.5 mM EGTA (as in A and B) (Left) or with the matrix solution containing 5 mM BAPTA with no added Ca2+ (as in C, Right and D) is abolished in the absence of matrix Mg2+. Bars: SEM, ***P < 0.0000009.

Matrix Ca2+ Buffering Regulates Matrix Ca2+ Regulation of MCU Ca2+-Channel Activity.

Whereas it was previously inferred that the EMRE carboxyl terminus could contribute to matrix Ca2+ sensing (27), its location in the IMS (8, 15, 25, 28) precludes a direct role. To identify matrix Ca2+-regulatory sites, we first considered whether MCU can be regulated by [Ca2+]i in the nanodomain created by Ca2+ flux through the channel, as is the case for plasma-membrane Ca2+ channels (29). Inhibition of such regulation by the fast Ca2+ buffer BAPTA but not by a slow buffer such as EGTA is considered evidence for permeant Ca2+ ion-flux regulation of channel activity (29, 30). To determine whether Ca2+ flux through MCU contributes to matrix [Ca2+] regulation of its activity, we replaced 1.5 mM EGTA with the same concentration of BAPTA. We reasoned that faster buffering might either eliminate matrix [Ca2+] regulation or shift the inhibitory [Ca2+]m to higher concentrations in the bulk solution, since we assumed that the local flux contribution would be reduced by faster buffering. Instead, BAPTA unexpectedly shifted the entire biphasic matrix [Ca2+] dependence to 10-fold lower concentrations (Fig. 1C). Conversely, reducing [BAPTA] from 1.5 mM to 0.5 mM shifted the biphasic dependence in the opposite direction (Fig. 1D). Incremental increases of [BAPTA] in the pipette solution shifted the biphasic matrix [Ca2+] dependence of MCU activity to even lower concentrations such that, at 5 mM BAPTA, only the maximal inhibition and recovery from inhibition could be observed (Fig. 1 C and D). A linear relationship in a semilog plot of [BAPTA] and the inhibitory [Ca2+]m (Fig. 1E) suggests that matrix Ca2+ buffering regulates a single dominant process that controls matrix [Ca2+] regulation of channel activity. Physiologically, mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ buffering capacity is provided by phosphate (Pi) (31). Matrix [Pi] also modulated [Ca2+]m regulation of MCU-channel activity (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Sensitivity of [Ca2+]m regulation of MCU activity to matrix BAPTA and Pi supports the suggestion that Ca2+ flux through the channel plays an important role in this process. Whereas it was expected that BAPTA would desensitize the channel to inhibition by matrix [Ca2+], the opposite was observed. Notably, the biphasic nature of matrix [Ca2+] regulation remained intact under different buffer regimes (Fig. 1D). This implies that the inhibitory Si and activating Sa Ca2+ sensors are coupled and jointly regulated indirectly by what we here term a low-affinity Ca2+-flux sensor Sf. The simplest model suggests that Ca2+ occupancy of Sf allosterically tunes the Ca2+ affinities of Si and Sa. When Sf is occupied, for example when matrix Ca2+ buffering is low, the apparent Ca2+ affinities of Si and Sa are low, resulting in the biphasic dependence shifted to higher matrix [Ca2+]. When Sf is unoccupied, for example when the matrix is buffered with 5 mM BAPTA, the apparent Ca2+ affinities of Si and Sa are high, resulting in the biphasic dependence shifted to very low [Ca2+]m.

Whereas this model can account for most of the results, strong channel inhibition observed in 5 mM BAPTA at very low [Ca2+]m (Fig. 1 C and D) was not predicted, since all matrix Ca2+-regulatory sites as well as the flux sensor should be unoccupied, and MICU1/2 was fully Ca2+-liganded under our recording conditions, which together would be expected to activate the channel. The pipette solutions in all of our Ca2+-current measurements contained 2 mM MgCl2, used historically to increase mitoplast electrical stability (26). We therefore considered that Mg2+ binding to the inhibitory Ca2+ sensor Si might underlie channel inhibition observed in high-[BAPTA]/low-[Ca2+]m. Remarkably, not only did removal of Mg2+ from the pipette solution completely abolish MCU-channel inhibition observed in 5 mM BAPTA, it also eliminated MCU-channel inhibition normally observed in 400 nM Ca2+/1.5 mM EGTA (Fig. 1F).

Identification of the Matrix Ca2+ Inhibition Sensor.

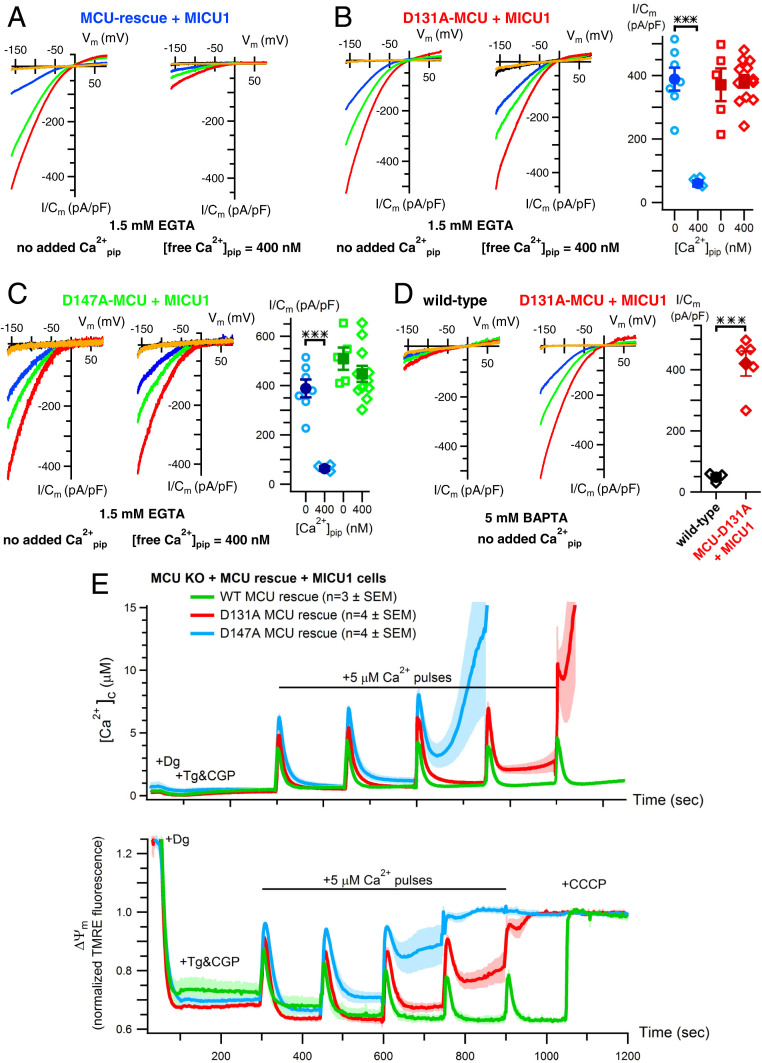

Previously, a structure of the isolated amino-terminal domain of human MCU, located in the mitochondrial matrix in the full-length channel (25, 28), revealed an acidic patch with a bound Mg2+ that was postulated to be a low-affinity divalent cation-binding site (32). We speculated that this site might be the structural basis for matrix [Ca2+] inhibition in full-length MCU. To test this, we individually mutated two key aspartic-acid residues important for divalent-cation binding (32)—D131 and D147—to alanines (D131A and D147A) and recorded Ca2+ currents through the mutant MCU channels following stable expression in MCU-knockout (KO) HEK cells overexpressing MICU1 to ensure proper regulation of the recombinant channels (33). Both mutant MCU channels expressed at somewhat higher levels than that of rescue wild-type MCU by Western blot analyses of isolated mitochondrial lysates, with MICU1/2 dimer expression similar among the different cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). However, with 1.5 mM EGTA and no added Ca2+ in the pipette solutions, Ca2+-current densities were not different between the mutant- and wild-type-MCU–expressing cells (Fig. 2 A–C), suggesting that the functional expression of the mutant and wild-type channels was equivalent among the lines. Importantly, normal channel inhibition by 400 nM [Ca2+]m (Fig. 1 A and B) was abolished in both MCU-mutant channels (Fig. 2 A–C). Furthermore, channel inhibition observed in high-[BAPTA]/low-[Ca2+]m (Fig. 1 D and E) was also abolished (Fig. 2D). In contrast, charge neutralization of E117, located in a distinct acidic patch in the amino terminus (32), in E117Q-MCU channels, was without effect on normal matrix [Ca2+] inhibition (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). These results indicate that the amino terminus of MCU contains a functional Ca2+-binding site encompassing residues D131 and D147 that accounts for matrix Ca2+ (and Mg2+) inhibition of channel activity. Occupancy of this site overrides normal cytoplasmic Ca2+-mediated MICU1/2 activation of channel activity to inhibit MCU. To independently test this, we measured intact-mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in digitonin-permeabilized cells in response to incremental boluses of 5 to 7 μM Ca2+. Low bath [Ca2+] before addition of Ca2+ pulses remained unchanged in response to inhibition of NCLX, the major mitochondrial Ca2+ extrusion mechanism, indicating that MCU was inactive in the low-[Ca2+]i regime (19). Thus, channel gatekeeping remained functional in D131A-, D147A-, and E117Q-MCU–expressing cells (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), indicating that the MCU/EMRE/MICU1/2 channel complex was intact in the cells expressing mutant MCU. The resting levels of [Ca2+]m in the mutant MCU-expressing cells were moderately elevated compared with that observed in the MCU-rescue cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). The rates of Ca2+ uptake in response to the first Ca2+ bolus were not different among the different cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B), consistent with the electrophysiological data that indicated that the functional expressions of wild-type and of mutant MCU channels were equivalent. Whereas mitochondria in MCU-KO cells rescued with wild-type MCU rapidly took up Ca2+ in response to 9 to 12 successive boluses, those in cells rescued with either D131A-MCU or D147A-MCU exhibited partial failure to take up Ca2+ after only two Ca2+ pulses, with complete failure observed after three or four pulses associated with collapse of ΔΨm (Fig. 2E), indicating matrix-Ca2+ overload-induced activation of the PTP. In contrast, cells rescued with E117Q MCU behaved similarly to wild-type MCU rescue cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). These results indicate that matrix Ca2+ regulation of MCU-channel activity observed in mitoplast electrophysiology is functional in intact mitochondria, with elevated matrix [Ca2+] feeding back to inhibit Ca2+ influx, mediated by the Ca2+-binding D131/D147 site in MCU. This feedback inhibition overrides cytoplasmic Ca2+-dependent MICU1/2 activation of MCU to prevent excessive mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and PTP opening.

Fig. 2.

The MCU amino terminus mediates matrix [Ca2+] inhibition of MCU. (A) Representative MCU Ca2+-current traces recorded from MCU-KO cells rescued with wild-type MCU and MICU1 (blue label) with pipette buffer and [Ca2+] as indicated. (B, Left) Similar, in MCU-KO cells rescued with D131A-MCU (red label). (B, Right) Summary of MCU Ca2+-current densities recorded in wild-type MCU and D131A-MCU mitoplasts with pipette solutions containing 0 or 400 nM free Ca2+ buffered with 1.5 mM EGTA. Bars: SEM, ***P = 0.0005. (C) Similar, in MCU-KO cells rescued with D147A-MCU. Bars: SEM, ***P = 0.0005. (D) MCU channel inhibition in 0 Ca2+/5 mM BAPTA (Left; black symbols in summary panel at Right; see also Figs. 1C and 3C) is abolished in mitoplasts expressing D131A-MCU (Middle; red symbols in summary panel). Bars: SEM, ***P = 0.0005. (E) Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and ΔΨm in digitonin-permeabilized cells in response to successive additions of 5 to 7 μM Ca2+ boluses in MCU-KO cells rescued with wild-type (WT) MCU and MICU1 (green; n = 3) or with D131A- (red; n = 4) or D147A- (blue; n = 4) MCU and MICU1. Traces show mean (solid line) ± SEM (shaded). Mitochondria in WT MCU-rescue cells are able to rapidly take up Ca2+ in response to 10 to 12 boluses (only 5 shown for comparison), whereas mutant MCU-rescue cells fail after three or four boluses, associated with collapse of ΔΨm, indicative of matrix Ca2+-induced PTP opening.

Interaction of Matrix [Ca2+] and MICU1/2 Regulation of MCU Activity.

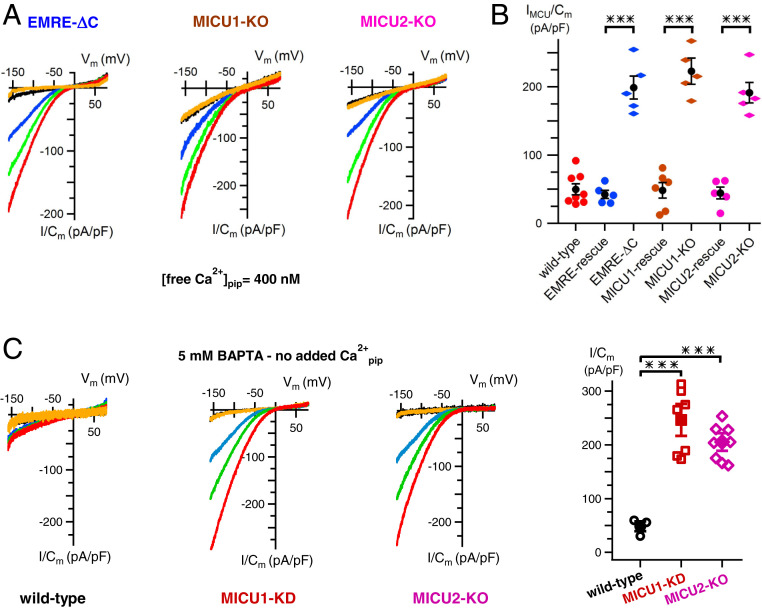

Strong inhibition of MCU-channel activity by matrix [Ca2+] occurred despite MICU1/2 being fully Ca2+-liganded by Ca2+ present in the bathing solution. To explore the relationship between matrix [Ca2+] regulation and MICU1/2-mediated cytoplasmic [Ca2+] regulation of MCU activity, we genetically knocked down/out MICU1 or MICU2, or inhibited their association with the channel complex by mutating the EMRE carboxyl terminus (15). We previously demonstrated that knockdown (KD) of either MICU1 or MICU2 or expression of mutant EMRE have no effects on MCU expression (19). Furthermore, Ca2+-current densities measured with 0 or 1 μM Ca2+ in the pipette solution were comparable in MICU KO and mutant EMRE-expressing cells to those in wild-type cells (27). However, each of these genetic interventions that abolish [Ca2+]i regulation of MCU channel activity also abolished matrix [Ca2+] regulation (Fig. 3 A and B and see also ref. 27). Reexpression of wild-type EMRE, MICU1, or MICU2 rescued normal matrix [Ca2+] regulation (Fig. 3B). Matrix [Ca2+] inhibition of channel activity observed with the pipette solution containing 5 mM BAPTA/0-Ca2+ (Fig. 1 C and D) was also fully abolished by genetic deletion of MICU1 or MICU2 (Fig. 3C). This result suggests that uncoupling of matrix [Ca2+] and MICU1/2 regulation could not account for channel inhibition observed in this high-[BAPTA]/low-[Ca2+]m condition. Together these results demonstrate that matrix [Ca2+] regulation of MCU activity depends on MICU1/2 association with the channel on the opposite side of the membrane, suggesting that matrix [Ca2+] and MICU1/2 regulation of MCU activity are tightly coupled.

Fig. 3.

Matrix [Ca2+] regulation of MCU requires the MICU1/2 heterodimer. (A) Representative MCU Ca2+ currents recorded with pipette free [Ca2+] = 400 nM in mitoplasts from cells lacking functional MICU1/2 regulation due to expression in EMRE KO cells of EMRE with its acidic carboxyl terminus deleted (EMRE-ΔC) (Left) or in MICU1- (Middle) or MICU2- (Right) KO cells. (B) Summary of MCU Ca2+-current densities recorded with matrix free [Ca2+] = 400 nM in mitoplasts from wild-type cells and EMRE-ΔC, MICU1- (Middle), or MICU2- (Right) KO cells, and their respective rescue cells. Loss of normal inhibition observed with matrix free [Ca2+] = 400 nM in cells lacking MICU1/2 regulation is rescued by expression of wild-type EMRE, MICU1, and MICU2. Bars: SEM, ***P < 0.00003. See also ref. 27. (C) Matrix [Ca2+] inhibition of MCU Ca2+-channel activity observed with pipettes containing 5 mM BAPTA and no added Ca2+ (Left; see also B) requires MICU1 (Middle) and MICU2 (Right; representative families of current recordings). (Far Right) Summary of Ca2+-current densities in mitoplasts recorded at −160 mV with 1 mM bath [Ca2+] with each point representing a single mitoplast. Bars: SEM, ***P = 0.0007 (MICU1) and P = 0.00009 (MICU2).

Regulation of MCU Na+ Currents.

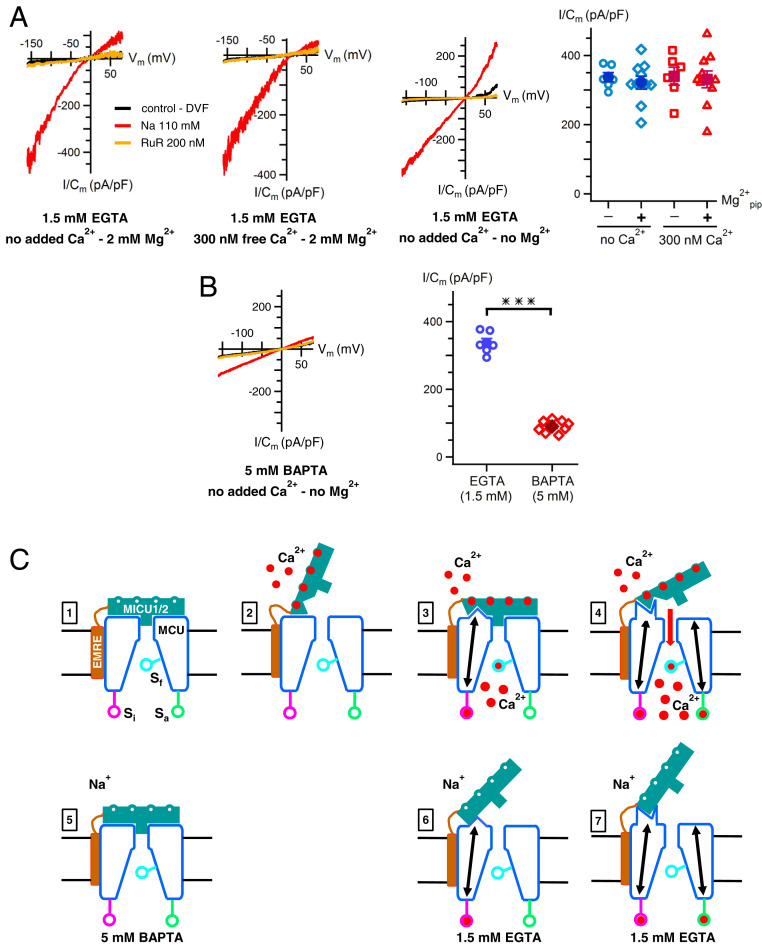

Whereas apo-MICU1/2 normally inhibits MCU-mediated Ca2+ influx in low [Ca2+]i (14, 18–22), it fails to inhibit MCU Na+ currents observed in the absence of Ca2+ as permeant ion (1, 26, 27). Furthermore, Na+ currents observed with matrix [Ca2+] buffered with 1.5 mM EGTA are independent of MICU1/2 association with the channel complex (27). We considered that Na+ currents are observed because they are recorded with pipette solutions lacking Mg2+ (1, 26, 27). However, addition of 2 mM Mg2+ to the pipette solutions did not inhibit the inward Na+ currents (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, whereas 300 to 400 nM Ca2+m buffered with 1.5 mM EGTA inhibited Ca2+ currents (Fig. 1 A and B), it was without effect on Na+ currents (Fig. 4A). In both conditions, the inhibitory D131/D147 Ca2+-sensor site was liganded, but it was no longer inhibitory with Na+ as the current carrier. Thus, under conditions in which Na+ is the current carrier, matrix [Ca2+]- and MICU1/2-regulation of MCU gating appear to be uncoupled. To explore this further, we examined the effects of high-[BAPTA]/low-[Ca2+]m/0-Mg2+ pipette solutions. Notably, Na+ currents were strongly inhibited in this condition (Fig. 4B). Thus, with sufficiently strong Ca2+ buffering to ensure that all matrix Ca2+ sensors are unoccupied, normal apo-MICU1/2 inhibition of MCU activity is similarly observed for Ca2+ influx and Na+ currents.

Fig. 4.

Regulation of MCU Na+ currents and a model for coupled matrix- and cytoplasmic-Ca2+ regulation. (A) MCU Na+ currents are not inhibited by matrix Ca2+ or Mg2+. First two panels: representative recordings of MCU-mediated Na+ currents in absence of added pipette Ca2+ (Left) and presence of 300 nM matrix Ca2+ (Right) with 2 mM Mg2+. Normal Ca2+-current inhibition by 300 nM matrix Ca2+ buffered with 1.5 mM EGTA (Fig. 1 A and B) is not observed for MCU Na+ currents. Inward rectification of Na+ currents caused by Mg2+ in the pipette solution. Third panel: representative recordings of MCU-mediated Na+ currents in absence of both matrix Ca2+ (1.5 mM EGTA) and Mg2+. Lack of Mg2+ results in linear Na+ currents. Fourth panel: summary data with pipette solutions containing 1.5 mM EGTA with 0 (blue) or 300 to 400 nM (red) Ca2+ with and without 2 mM Mg2+. Data for 0 Mg2+/400 nM Ca2+ from ref. 27. Bars: SEM. No significant differences among groups. (B, Left) Representative Na+ current recordings with pipette solution containing 0 Mg2+ and 0 Ca2+/5BAPTA. (B, Right) Summary demonstrating inhibition of MCU Na+ currents by strong Ca2+ buffering in absence of matrix Mg2+. Bars: SEM, ***P = 4 E-10. (C) Cartoon models of MCU-channel regulation by coupled MICU1/2 and matrix [Ca2+] mechanisms. Numbers 1 through 4 depict physiological cytoplasmic- and matrix [Ca2+] regulation of MCU-channel open probability. Numbers 5 through 7 depict regulation of experimental MCU-mediated Na+ currents. MICU1 and MICU2 are depicted as a single entity (MICU1/2) facing the IMS with 4 Ca2+-binding sites. Distinct functional conformations of MICU1/2 and MCU are depicted, with comparable conformations in Ca2+- and Na+-permeation experiments aligned vertically. Pore block depictions in 1, 3, and 5 are meant to reflect inhibited MCU activity rather than a particular molecular mechanism. Arrows within MCU denote conformational changes in MCU associated with Ca2+ binding to inhibitory (Si), activating (Sa), and flux (Sf) sensor sites. See text for details.

Discussion

Previous studies of intact mitochondria in permeabilized cells (11, 12, 14, 18–22) and in mice (23, 24, 34) and humans (35–37) have suggested important roles for IMS-localized MICU1/2 in MCU regulation by cytoplasmic [Ca2+]. Our results indicate that cytoplasmic MICU1/2 regulation of MCU is not an independent channel regulatory mechanism but is instead regulated by Ca2+ sensors located in the matrix, at least one of which is an integral component of the channel pore-forming subunit. A model that can account for our data is schematized in Fig. 4C. In the low-[Ca2+]i regime characteristic of resting conditions in the cytoplasm, MICU1/2 in its apo conformation maintains MCU in a closed-channel conformation, either by inhibiting channel gating or, more likely, by physically occluding the permeation pathway (25) (Fig. 4 C, 1). Maintenance of this inhibited channel conformation may also be facilitated by matrix Ca2+, since we observed relatively strong inhibition of MCU Ca2+ currents even at 100 nM, the physiological resting matrix [Ca2+]. In the presence of elevated cytoplasmic [Ca2+], either physiologically or when recording Ca2+ currents in mitoplast electrophysiology, Ca2+ binding to MICU1/2 induces a conformational switch (25, 38–41) that relieves channel inhibition imposed by the apo conformation, and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (11–14, 18–22) and Ca2+ currents (1, 26, 27, 42) can be recorded (Fig. 4 C, 2). Ca2+ influx promotes Ca2+ binding to a flux sensor, which in turn tunes the affinities of other, coupled inhibitory and activating Ca2+-sensor sites located in the matrix. The evidence for this was revealed by the biphasic matrix [Ca2+] dependence of MCU Ca2+ current densities, and the effects of the fast Ca2+ buffer BAPTA in the matrix on MCU channel activity. The biphasic nature of the relationship remained intact as BAPTA concentration was increased, suggesting that the inhibitory and activating sites are coupled and jointly regulated by a sensor that is sensitive to bulk matrix Ca2+-buffering capacity. Because BAPTA at the same concentration as the slower Ca2+ buffer EGTA also shifted the matrix [Ca2+] dependence in a manner similar to that of simply increasing buffer capacity, we assume that the sensor that regulates the coupled inhibitory and activating sites is located within a region of high Ca2+ concentration that cannot be well buffered by EGTA. The source of this Ca2+ is most likely the Ca2+ that permeates through the channel pore. Accordingly, we have termed this the flux sensor. Its physical location remains to be determined, but we speculate that it could be an internal Ca2+-binding site associated within the channel selectivity filter (43) [we note that Ca2+ remained bound in the selectivity filter in the MCU/EMRE/MICU1/2 complex structure solved in 5 mM EGTA with no added Ca2+ (25)] or localized at a putative inner gate at the bottom of the cavity below the pore (28). With the flux sensor and the inhibitory site, which we localized to the MCU amino terminus, fully Ca2+-liganded, MCU channel activity is strongly reduced even with MICU1/2 fully Ca2+-liganded (Fig. 4 C, 3). In the presence of 1.5 mM EGTA, maximal inhibition of ∼80% is observed when matrix [Ca2+] is ∼400 nM. Two lines of evidence suggest that these observations in mitoplasts with artificial buffers are physiologically relevant. First, we demonstrated that changes in the matrix [Pi], the major mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ buffer in situ, also affected matrix Ca2+ regulation of MCU channel open probability, although the experiments were complicated by the low Ca2+ affinity of Pi. Second, we demonstrated the existence and importance of matrix [Ca2+] regulation of MCU channel activity in situ in intact mitochondria by Ca2+-uptake assays in permeabilized cells expressing mutant MCU channels that lacked matrix Ca2+ inhibition of mitoplast Ca2+ currents. These mitochondria underwent Ca2+-induced PTP opening associated with a collapse of the ΔΨm in response to Ca2+ transients that were without detrimental effects on mitochondria expressing wild-type MCU (with matrix Ca2+ inhibition intact). Importantly, inhibition of MCU-channel activity by matrix Ca2+ depends upon the presence of MICU1/2 within the channel complex. The evidence for this was the lack of matrix [Ca2+] inhibition of MCU Ca2+ currents in cells lacking MICU1 or MICU2, and also in cells in which the heterodimer MICU1/2 was not functional due to the absence of its EMRE-mediated tethering to the channel complex. This suggests that Ca2+ binding to the matrix inhibitory site in the amino terminus of MCU results in a conformational change in MCU that enables Ca2+-bound MICU1/2 to inhibit its activity (Fig. 4 C, 3), by pore block or inhibiting channel gating. In contrast, the data suggest that matrix Ca2+ binding to the lower-affinity activating site induces a different channel conformation that no longer accommodates Ca2+-liganded MICU1/2, enabling Ca2+ permeation (Fig. 4 C, 4). Failure to account for the fundamental modulation by matrix [Ca2+] of MICU1/2 regulation may result in an inability to observe MICU1/2 regulation of Ca2+ currents by patch-clamp electrophysiology if the pipette [Ca2+] is either too high or too low, depending upon the matrix Ca2+-buffering properties (1, 44). For example, Hoffman et al. (10) reported enhanced Ca2+ currents in MICU1-KD mitoplasts compared with those observed in wild-type mitoplasts, whereas we have observed no difference (27). Whereas both studies employed similar patch-pipette solutions containing 1.5 mM EGTA, Hoffman et al. (10) challenged mitoplasts with 5 mM bath Ca2+ compared with 1 mM Ca2+ in our studies. It is likely that the approximately fivefold greater flux was not adequately buffered, leading to an increase in the matrix [Ca2+] and consequent inhibition of MCU activity recorded from wild-type mitoplasts. Because [Ca2+]m regulation of MCU channel activity is absent in MICU1-KD mitoplasts, the MCU Ca2+ currents would be larger than in the wild type, as observed. MICU1/2 regulation of Na+ currents was only revealed under conditions that strongly minimized occupancy of all matrix Ca2+ sensors (Fig. 4 C, 5). Because this has not been previously considered (Fig. 4 C, 6 and 7), it can explain why the channel has been observed to be constitutively active when Na+ currents are measured (1, 26, 27, 44).

Our results indicate that Ca2+ occupancy of matrix Ca2+ sensors regulates MCU channel-conformational states that determine the efficacy of MICU1/2 regulation. Previously, regulation of MCU channel activity was defined by cytoplasmic Ca2+ modulation of MICU1/2 that sets a [Ca2+]i threshold for MCU channel activity and its cooperative activation. Our results indicate that this regulation is set not only by the Ca2+ affinities of MCU1/2 EF hands but also by matrix [Ca2+] and buffering capacity, allowing for enhanced cellular regulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis. The importance of this enhanced regulation is reflected by the different behaviors of mitochondria expressing D131A or D147A MCU mutants. These mutations abolished the matrix Ca2+ regulation of mitoplast Ca2+ currents, leaving only the cytoplasmic MICU1/2-dependent gatekeeping mechanism to protect mitochondria from Ca2+ overload. Although this mechanism was sufficient to protect these mitochondria at resting cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C), it was insufficient in the absence of matrix Ca2+ regulation, as evidenced by PTP opening when the mitochondria were challenged with Ca2+ boluses (Fig. 2E).

Recent studies demonstrated a direct biochemical interaction of MICU1/2 with the MCU selectivity filter (16, 17). Because mutations in either MCU or MICU1 that disrupt this interaction lead to a constitutively open channel, it was suggested that MICU1/2 could possibly function as a classic channel pore blocker (17). Recent structural data strongly support this model (25). Our results here indicate that structural changes that affect this interaction are localized not only in MICU1/2 (38–41), regulated by cytoplasmic Ca2+, but also in the MCU channel itself, regulated by Ca2+ sensors localized on the opposite side of the IMM. We suggest that the structural plasticity of the MCU–MICU interface enables MCU-channel regulation to be dependent upon Ca2+ levels in both the cytoplasm and mitochondrial matrix. This mechanism is reminiscent of Ca2+-dependent inactivation of plasma membrane voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC). There, Ca2+ flux through the channel pore interacts with channel elements in the cytoplasm that results in structural changes in the selectivity filter on the other side of the membrane that close the channel (45). Similarly, voltage-dependent inactivation of VGCC involves elements in the cytoplasmic aspect of the channel that drive conformational changes near to the ion-conducting pore (45, 46). Alternately, it has been suggested that MCU may possess an internal gate at the base of the internal central cavity below the selectivity filter (28). It is possible that structural changes regulated by MICU1/2 and matrix Ca2+ sensors regulate this gate. An important goal now is to understand how Ca2+ binding to mitochondrial matrix sensors is transduced into conformational changes of the MCU channel that affect MCU interactions with MICU1/2 to regulate Ca2+ permeation.

The importance of the mechanisms described here for other cell types remains to be determined. Quantitative differences of MCU activity exist among mitochondria in various tissues (26), and MCU regulation in the heart may be different from that in other tissues by lack of a MICU1/2 “gatekeeping” mechanism, employing instead low MCU-channel density to enable Ca2+ intake to be effectively compensated for by the extrusion activity of NCLX (4, 47). In a preliminary electrophysiology study of mitoplasts from mouse embryonic fibroblasts lacking DRP1, it was suggested that MICU1/2 inhibition of MCU channel activity (“gatekeeping”) does not exist, and that matrix [Ca2+] regulation of MCU activity is absent (44). With regard to the former, a cryo-electron microscopic analysis of the human MCU/EMRE/MICU1/2 complex revealed a structural basis for channel “gatekeeping” by observing that apo-MICU1/2 physically occludes the channel pore (25), strongly supporting numerous studies that have demonstrated the role of apo-MICU1/2 in maintaining the MCU channel in an off state in resting cytoplasmic [Ca2+] conditions. With regard to the latter, we point out that [Ca2+] in the pipette solutions used was not measured, only one calculated [Ca2+] was tested, and the possible role of matrix [Mg2+] was not considered. Future studies will be necessary to clarify these controversies.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines, Constructs, and Antibodies.

Wild-type HEK-293T and KO cell lines were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. MCU-KO, MICU1-KO, and MICU2-KO HEK-293T cells were a generous gift from Vamsi Mootha, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. Full-length MICU1, MICU2, and EMRE complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were purchased from Origene Technologies USA. EMRE-ΔC-V5 constructs were generated by a PCR-based cloning strategy as described (27). All constructs were sequence-verified and stably transfected into KO backgrounds. D131A-MCU-Flag and D147A-MCU-Flag cDNAs in pCMV6-A-BSD were a gift from Muniswamy Madesh, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX. E117Q-MCU-V5-His in pCMV6-A-Puro was generated using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit and XL10-Gold ultracompetent Escherichia coli. All MCU constructs were sequence-verified and stably transfected in the MCU-KO backgrounds together with MICU1. MCU WT-rescue or mutant cells were grown in complete DMEM supplemented either with blasticidin (5 μg/mL), puromycin (2 μg/mL), or both, until stable expression of each plasmid was achieved. Clones were isolated by limiting dilution for each condition and maintained in complete medium with antibiotics. Exclusive mitochondrial localization was verified by immunofluorescence. Only clones expressing recombinant proteins in all mitochondria in all cells were selected for experimentation.

Uniporter Electrophysiology.

Mitoplast electrophysiology was performed as described (1, 26, 27). Patch pipettes had resistances of 20 to 60 MΩ when filled with (in millimolar): 120 TMA-OH, 120 Hepes, 80 d-gluconic acid, 10 glutathione, and 2 MgCl2, pH = 7.0, with d-gluconic acid; osmolarity was 390 to 450 mOsm/kg. EGTA or BAPTA were used, as specified, to buffer correspondent amounts of CaCl2 for [Ca2+]free ≤400 nM (confirmed by Ca2+-sensitive dye fluorimetry). The free [Mg2+] ([Mg2+]free, assessed using MaxChelator software (https://somapp.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/pharmacology/bers/maxchelator/webmaxc/webmaxcE.htm), was not significantly affected by the different Ca2+ chelators used in our study: In 5 mM and 0.5 mM BAPTA, [Mg2+]free = 1.8 mM and 2.0 mM, respectively. Mitoplasts were initially bathed in (in millimolar): 150 KCl, 10 Hepes, and 1 EGTA, pH = 7.2; osmolarity was 300 mOsm/kg (“KCl-DVF” solution). Voltage pulses (350 to 500 mV for 15 to 50 ms) were delivered by the PClamp-10 (Molecular Devices) program to obtain the “whole-mitoplast” configuration. Access resistance (30 to 90 MΩ) and mitoplast capacitance Cm (0.2 to 1 pF) were determined using the membrane test protocol of the PClamp-10 software. After the whole-mitoplast configuration was obtained, the KCl-DVF bath solution was exchanged with Hepes-EGTA (in millimolar: 150 Hepes and 1.5 EGTA, pH = 7.0, with Tris base) for baseline measurements and then replaced with Hepes-0-EGTA solutions with 0.1, 0.3, or 1 mM CaCl2 successively. Finally, a Hepes-based solution with 1 mM CaCl2 and 200 nM ruthenium red (RuR) was perfused into the bath to record the final baseline (= IRuR) after block of the MCU currents. Osmolarities of bath solutions were 297 to 305 mOsm/kg, adjusted with sucrose. The voltage protocol, delivered by the PClamp-10 software with a DigiData-1550 interface (Molecular Devices), consisted in stepping the command membrane voltage Vm from 0 mV to −160 mV for 20 ms, followed by ramping to 80 mV (rate of 279 mV/s), dwelling at 80 mV for 20 ms, and returning to 0 mV. Currents were recorded using an Axopatch 200-B amplifier at room temperature with a sampling rate of 50 kHz and antialiasing-filtered at 1 kHz. Data analysis was performed with the PClamp-10 software. For quantitative comparisons, current densities are defined as: IMCU/Cm = (ICa – IRuR)/Cm, with ICa and IRuR measured at Vm = −160 mV in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+ in the bath.

Simultaneous Measurements of Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake and Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in Permeabilized Cells.

Concurrent measurements of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and IMM potential (ΔΨm) in permeabilized HEK-293T cells were performed as described (18). Cells were grown in 10-cm tissue culture-coated dishes for 48 h prior to each experiment; 6 to 8 × 106 cells were trypsinized, counted, and washed in a Ca2+-free extracellular-like medium, centrifuged, suspended in 1.5 mL of intracellular-like medium (ICM, in millimolar: 120 KCl, 10 NaCl, 1 KH2PO4, 20 Hepes, and 5 succinate [pH 7.2]) that had been treated with BT Chelex 100 resin before use to attain an initial free [Ca2+] of ∼20 nM, and transferred to a cuvette. The cuvette was placed in a temperature-controlled (37 °C) experimental compartment of a multiwavelength-excitation dual wavelength-emission high-speed spectrofluorometer (Delta RAM; Photon Technology International). Membrane-impermeable Fura2 K+ salt (dissocation constant [KD] = 140 nM) or FuraFF K+ salt (KD = 5.5 µM) (final concentration 1 µM) and tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) (final concentration 1 µM) were added at time t = 25 s from the start, to measure bath [Ca2+]c and ΔΨm concurrently. Fluorescence at 549-nm excitation/595-nm emission for TMRE, along with 340-nm and 380-nm excitation/535-nm emission for Fura2/FuraFF, was measured at 5 Hz; 40 µg/mL digitonin was added at t = 50 s to permeabilize cells and allow the cytoplasm to equilibrate with the bath solution such that the degree of quenching of TMRE fluorescence reports the relative ΔΨm. Fura2/FuraFF fluorescence under these conditions is related to the cytoplasmic [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]c) according to

where (R) is the measured fluorescence ratio (340/380 nm), (Rmin) is the fluorescence ratio under 0 [Ca2+], (Rmax) is the fluorescence ratio under saturating [Ca2+], (Sf2) and (Sb2) are the absolute 380-nm excitation/535-nm emission fluorescence under 0 [Ca2+] and saturating [Ca2+], respectively, and (KD) is the dissociation constant of the dye for Ca2+. Thapsigargin (2 µM) and CGP37157 (20 µM) were added at 100 s to inhibit Ca2+ uptake into the endoplasmic reticulum and NCLX-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ extrusion, respectively. After [Ca2+]c reached a steady state at ∼300 s, MCU-mediated Ca2+ uptake was initiated by adding a bolus of 5 µL of 5 mM CaCl2 to the cuvette to achieve increases in [Ca2+]c between ∼5 µM. The volume of CaCl2 required to achieve the desired increase in [Ca2+]c was calculated based on the activity coefficient for Ca2+ in ICM. After [Ca2+]c was monitored for 150 s following Ca2+ addition, a second bolus of CaCl2 was added. This procedure was repeated for a total of five to nine successive additions of Ca2+; 150 s after addition of the final bolus, CCCP (2 µM) was added to uncouple ΔΨm and allow unimpeded Ca2+ efflux from mitochondria as a measure of the total extent of uptake. Under our conditions, each Ca2+ bolus caused a transient depolarization as measured with TMRE that recovered after ∼50 to 60 s. Concurrent failure of Ca2+ uptake and loss of ΔΨm indicates opening of the mitochondrial PTP.

Initial Ca2+ uptake rates in permeabilized cells were determined for each experiment using single-exponential fits from the time of the first Ca2+ addition (t = 0 s) to achievement of a new steady state (t = 300 s) to obtain parameters A (extent of uptake) and τ (time constant) (IGOR Pro; Research Resource Identifier [RRID]: SCR_000325). The instantaneous rate of uptake (R) at t = 0 is equal to the first derivative of the fit, and SDs of rates were calculated from SDs of A (SDA) and τ (SDτ) as follows:

For determination of the steady-state [Ca2+]c after completion of uptake (gatekeeping threshold [Ca2+]c), the calculated [Ca2+]c 300 s after challenge with 0.1 to 10 µM Ca2+ (Y) was plotted as a function of the (peak) initial [Ca2+]i achieved after bolus Ca2+ addition (X). Data were fitted using a one-phase association model where (Y0) is the Y value when X is zero, (P) is the plateau, or Y value at infinite X, and (K) is the rate constant, expressed in reciprocal of the x axis:

The value of (P) represents to the steady-state [Ca2+]c at which gatekeeping is reestablished ± the SE of (P) determined from the fit.

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis Western Blotting.

For Western blots of mitochondrial proteins, mitochondria were isolated as described (6). Total protein concentrations were calculated using BCA Protein Assay kit (23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and samples for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) were prepared in 2× Laemmli sample buffer (1610737; Bio-Rad) ± 2-mercaptoethanol (βME) (1610710; Bio-Rad). NuPAGE gels (4 to 12%, NP0321; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were transferred to Immobilon P poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes (IPVH00010; Millipore-Sigma) and probed with various antibodies. Antibodies used were anti-MCU (14997S; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-V5 tag (13202S; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-MICU2 (ab101465; Abcam), anti-DYKDDDDK (Flag tag) (14793S; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-MICU1 (12524S; Cell Signaling Technology), anti–β-tubulin (32-2600; Invitrogen), and anti-Hsp60 (ab46798; Abcam). Membranes were blocked in 5% fat-free milk for 1 h at room temperature (RT), incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody, and then for 1 h at RT with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG)–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (7074S; Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-mouse IgG–HRP (7076S; Cell Signaling Technology) secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP. Chemiluminescence detection was carried out using SuperSignal West Chemiluminescent Substrate (34580; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mean pixel density of bands was quantified using the Fiji software package in ImageJ (RRID: SCR_003070), corrected for the intensity of the loading-control band (β-tubulin for whole-cell lysates or Hsp60 for isolated mitochondria), and normalized to the response in wild-type cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Francesca Fieni and Yuri Kirichok for advice regarding mitoplast electrophysiology and Dr. Don-On Daniel Mak for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH Grant R37 GM56328.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2005976117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All data relevant to the conclusions of the manuscript are included in the paper or in SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Kirichok Y., Krapivinsky G., Clapham D. E., The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature 427, 360–364 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottschalk B. et al., MICU1 controls cristae junction and spatially anchors mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter complex. Nat. Commun. 10, 3732 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nemani N., Shanmughapriya S., Madesh M., Molecular regulation of MCU: Implications in physiology and disease. Cell Calcium 74, 86–93 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wescott A. P., Kao J. P. Y., Lederer W. J., Boyman L., Voltage-energized calcium-sensitive ATP production by mitochondria. Nat. Metab. 1, 975–984 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baughman J. M. et al., Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476, 341–345 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Stefani D., Raffaello A., Teardo E., Szabò I., Rizzuto R., A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476, 336–340 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sancak Y. et al., EMRE is an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex. Science 342, 1379–1382 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto T. et al., Analysis of the structure and function of EMRE in a yeast expression system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857, 831–839 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovács-Bogdán E. et al., Reconstitution of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 8985–8990 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman N. E. et al., MICU1 motifs define mitochondrial calcium uniporter binding and activity. Cell Rep. 5, 1576–1588 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perocchi F. et al., MICU1 encodes a mitochondrial EF hand protein required for Ca2+ uptake. Nature 467, 291–296 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plovanich M. et al., MICU2, a paralog of MICU1, resides within the mitochondrial uniporter complex to regulate calcium handling. PLoS One 8, e55785 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patron M. et al., MICU1 and MICU2 finely tune the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter by exerting opposite effects on MCU activity. Mol. Cell 53, 726–737 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrungaro C. et al., The Ca2+-dependent release of the Mia40-induced MICU1-MICU2 dimer from MCU regulates mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Cell Metab. 22, 721–733 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai M. F. et al., Dual functions of a small regulatory subunit in the mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex. eLife 5, e15545 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paillard M. et al., MICU1 interacts with the D-ring of the MCU pore to control its Ca2+ flux and sensitivity to Ru360. Mol. Cell 72, 778–785.e3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips C. B., Tsai C. W., Tsai M. F., The conserved aspartate ring of MCU mediates MICU1 binding and regulation in the mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex. eLife 8, e41112 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Csordás G. et al., MICU1 controls both the threshold and cooperative activation of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. Cell Metab. 17, 976–987 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payne R., Hoff H., Roskowski A., Foskett J. K., MICU2 restricts spatial crosstalk between InsP3R and MCU channels by regulating threshold and gain of MICU1-mediated inhibition and activation of MCU. Cell Rep. 21, 3141–3154 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamer K. J., Mootha V. K., MICU1 and MICU2 play nonredundant roles in the regulation of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. EMBO Rep. 15, 299–307 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamer K. J., Grabarek Z., Mootha V. K., High-affinity cooperative Ca2+ binding by MICU1-MICU2 serves as an on-off switch for the uniporter. EMBO Rep. 18, 1397–1411 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallilankaraman K. et al., MICU1 is an essential gatekeeper for MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake that regulates cell survival. Cell 151, 630–644 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J. C. et al., MICU1 serves as a molecular gatekeeper to prevent in vivo mitochondrial calcium overload. Cell Rep. 16, 1561–1573 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antony A. N. et al., MICU1 regulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake dictates survival and tissue regeneration. Nat. Commun. 7, 10955 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan M. et al., Structure and mechanism of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter holocomplex. Nature 582, 129–133 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fieni F., Lee S. B., Jan Y. N., Kirichok Y., Activity of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter varies greatly between tissues. Nat. Commun. 3, 1317 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vais H. et al., EMRE is a matrix Ca2+ sensor that governs gatekeeping of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. Cell Rep. 14, 403–410 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y. et al., Structural mechanism of EMRE-dependent gating of the human mtochondrial calcium uniporter. Cell 177, 1252–1261.e13 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parekh A. B., Ca2+ microdomains near plasma membrane Ca2+ channels: Impact on cell function. J. Physiol. 586, 3043–3054 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neher E., Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: New tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron 20, 389–399 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholls D. G., Mitochondria and calcium signaling. Cell Calcium 38, 311–317 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee S. K. et al., Structural insights into mitochondrial calcium uniporter regulation by divalent cations. Cell Chem. Biol. 23, 1157–1169 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Payne R., Li C., Foskett J. K., Variable assembly of EMRE and MCU creates functional channels with distinct gatekeeping profiles. iScience 23, 101037 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bick A. G. et al., Cardiovascular homeostasis dependence on MICU2, a regulatory subunit of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E9096–E9104 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis-Smith D. et al., Homozygous deletion in MICU1 presenting with fatigue and lethargy in childhood. Neurol. Genet. 2, e59 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Logan C. V. et al.; UK10K Consortium , Loss-of-function mutations in MICU1 cause a brain and muscle disorder linked to primary alterations in mitochondrial calcium signaling. Nat. Genet. 46, 188–193 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shamseldin H. E. et al., A null mutation in MICU2 causes abnormal mitochondrial calcium homeostasis and a severe neurodevelopmental disorder. Brain 140, 2806–2813 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L. et al., Structural and mechanistic insights into MICU1 regulation of mitochondrial calcium uptake. EMBO J. 33, 594–604 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu W. et al., The crystal structure of MICU2 provides insight into Ca2+ binding and MICU1-MICU2 heterodimer formation. EMBO Rep. 20, e47488 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xing Y. et al., Dimerization of MICU proteins controls Ca2+ influx through the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. Cell Rep. 26, 1203–1212.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamer K. J., Jiang W., Kaushik V. K., Mootha V. K., Grabarek Z., Crystal structure of MICU2 and comparison with MICU1 reveal insights into the uniporter gating mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 3546–3555 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vais H. et al., MCUR1, CCDC90A, is a regulator of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Cell Metab. 22, 533–535 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baradaran R., Wang C., Siliciano A. F., Long S. B., Cryo-EM structures of fungal and metazoan mitochondrial calcium uniporters. Nature 559, 580–584 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garg V., et al. , The mechanism of MICU-dependent gating of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. bioRxiv:10.1101/2020.04.04.025833 (5 April 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Abderemane-Ali F., Findeisen F., Rossen N. D., Minor D. L. Jr., A selectivity filter gate controls voltage-gated calcium channel calcium-dependent inactivation. Neuron 101, 1134–1149.e3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J. F., Ellinor P. T., Aldrich R. W., Tsien R. W., Molecular determinants of voltage-dependent inactivation in calcium channels. Nature 372, 97–100 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paillard M. et al., Tissue-specific mitochondrial decoding of cytoplasmic Ca2+ signals is controlled by the stoichiometry of MICU1/2 and MCU. Cell Rep. 18, 2291–2300 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the conclusions of the manuscript are included in the paper or in SI Appendix.