Abstract

Purpose of the Review

Functionally irreparable rotator cuff tears (FIRCTs) remain one of the most challenging pathologies treated in the shoulder. The lower trapezius transfer represents a very promising treatment option for posterosuperior FIRCT. This article reviews the role for the lower trapezius transfer in the treatment of patient with FIRCTs and highlights the tips and tricks to performing this arthroscopic-assisted procedure.

Recent Findings

The treatment of posterosuperior FIRCTs contemplates a wide array of surgical options, including partial repair, biceps tenodesis/tenotomy, superior capsule reconstruction, subacromial balloon, reverse shoulder arthroplasty, and open-/arthroscopic-assisted tendon transfers. Tendon transfers have emerged as very promising reconstructive options to rebalance the anterior-posterior force couple. Controversy remains regarding the relative indications of latissimus dorsi transfer (LDT) and lower trapezius transfer (LTT). Initially used with very good success in patients with brachial plexus injuries, the open LTT has shown excellent clinical and radiographic outcomes in a recent series of patients with FIRCTs. However, this technique should be reserved for patients with an intact or reparable subscapularis tendon and no advanced glenohumeral arthritis or humeral head femoralization. With advancements in surgical technique, the arthroscopic-assisted LTT has shown similar promising results. However, studies on arthroscopically assisted LTT are limited to short-term follow-up, and future comparative trials with large patient numbers and longer follow-up are needed to better understand the indications for this novel tendon transfer in the treatment of FIRCT.

Summary

The arthroscopic-assisted LTT is a novel, promising option for the treatment of patients with functional irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Careful attention to indications and technical pearls are paramount when performing this procedure to optimize postoperative clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Massive rotator cuff tear, Tendon transfers, Lower trapezius tendon transfer, Rotator cuff repair, Irreparable rotator cuff tear, Arthroscopically assisted

Introduction

Massive rotator cuff tears in both the primary and revision setting commonly lead to severe shoulder pain and loss of function. The natural history of these tears if left untreated involves a predictable progression to arthritic changes [1–3]. They are characterized by their tendon retraction, poor tendon quality, and fatty muscle infiltration, all leading to the shoulder dysfunction and morbidity experienced by patients [4–7]. Although the definition of irreparability is controversial, many studies have shown worrisome re-tear rates ranging from 20 to 94%, often associated with poor clinical outcomes [8–11]. Therefore, even if the tear can be physically repaired to the rotator cuff footprint, many large tears are considered to be functionally irreparable rotator cuff tears (FIRCTs).

A patient with a FIRCT without arthritis may be offered a variety of treatment options, including partial repair [12–16], augmentation or bridging with allografts [17–22], superior capsular reconstruction [23–26], subacromial balloon [27], shoulder tendon transfers [28–39], and reverse shoulder arthroplasty [40–43]. The ultimate goal of all of these treatment options involves providing a stable fulcrum for the humeral head to rotate, either through an implant, static graft, or restoration of the anterior-posterior force couple. Tendon transfers represent a promising option to treat patients with FIRCTs, providing a dynamic replacement for the posterior aspect of the force couple. Although the latissimus dorsi transfer (LDT) historically has been historically associated with reliable outcomes in selected patients with posterosuperior FIRTCs [28–36], the lower trapezius transfer has emerged as a promising alternative that is potentially biomechanically superior and easier for patients to retrain [35, 37, 38, 44].

“Functionally” Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears

Definition of Irreparability

The true definition of an irreparable rotator cuff tear is controversial given the multiple factors to consider, including patient factors, chronicity, imaging findings, and previous surgeries. However, all of these are critical to consider when deciding on whether or not to attempt a rotator cuff repair in the setting of a massive tear; as mentioned before, re-tear rates and associated clinical failures with these repairs can range from 20 to 94% [8–11].

Certain patient factors that may increase the risk of re-tear after an attempted repair include diabetes [45, 46], smoking [47], older age [46, 48], inflammatory arthritis [49], osteoporosis [50], and immunocompromised status [51]. Additionally, physical examination maneuvers can provide an insight on the size and chronicity of the tears, such as an external rotation lag sign [52]. Although not to be taken in isolation, when combined with other imaging or pathologic findings, they help the surgeon to determine the reparability of the tears.

One of the most important considerations when evaluating for FIRCTs involves the true chronicity of the tear. After the tear occurs, the involved rotator cuff tendon and muscle undergo a predictable pattern of degeneration over time, involving muscle shortening and retraction in the first year, followed by tendon shortening and muscle fatty infiltration in the following 2–4 years [53, 54]. This degenerative process influences the reparability of the tendon(s), including its intrinsic ability to heal back to the bone and functionally restore the shoulder’s coronal or axial force couple. An example of the influence of this process can be seen with improved healing rates and associated clinical outcomes within 6 months of a traumatic event [6, 55, 56].

Imaging plays a critical role in evaluating the chronicity of these tears and their ultimate reparability. Grashey and axillary radiographs might show humeral head superior or anterior subluxation, both late findings in the rotator cuff degenerative pathway. Computerized tomography arthrograms (CTA) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) represent a critical part to evaluating the quality of the rotator cuff and its potential reparability. Muscular fatty infiltration, visualized either via CTA [57] or MRI [58] on coronal or sagittal views, might be one of the most critical considerations when deciding the reparability and ultimate best treatment option (Fig. 1). Consistently throughout the last two decades, higher grades of fatty infiltration have been associated with worse outcomes and rates of rotator cuff healing [1, 6, 55, 59]. Additionally, tendon retraction to the level of the glenoid (Patte Classification [60] Grade 3) and a tendon length < 15 mm [59] have also been associated with worse clinical outcomes and higher re-tear rates. Combining advanced fatty infiltration, retraction to the level of the glenoid, and a tendon length < 15 mm, the specificity for an irreparable tear is 98% [61].

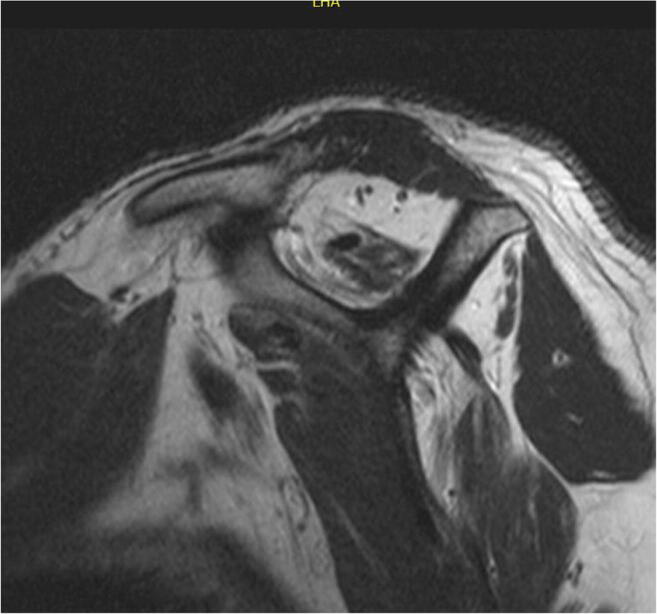

Fig. 1.

Fatty infiltration. A sagittal T1 view on an MRI shows advanced fatty infiltration (Grade 4 [1]) of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons

Biomechanics of Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears

The idea behind the “functional” definition of irreparable rotator cuff tears deals with the biomechanical impact on the shoulder. In a healthy shoulder, the rotator cuff serve as the primary dynamic stabilizers of the humeral head, not only contributing to shoulder motion directly but also providing stability to allow the other muscles (e.g., deltoid) to power shoulder function [62]. Glenohumeral motion and its associated scapulohumeral rhythm requires a balance of these dynamic stabilizers, creating a force couple [62] and a coordinated equilibrium for humeral rotation [63]. However, when a rotator cuff tendon is either torn or functionally inadequate, the anterior-posterior force couple is lost, and the associated glenohumeral contact pressure is altered, leading to translation of the humeral head during motion [64]. This instability and dynamic translation compromises the patient’s function and underlies their associated pain and morbidity (Fig. 2).

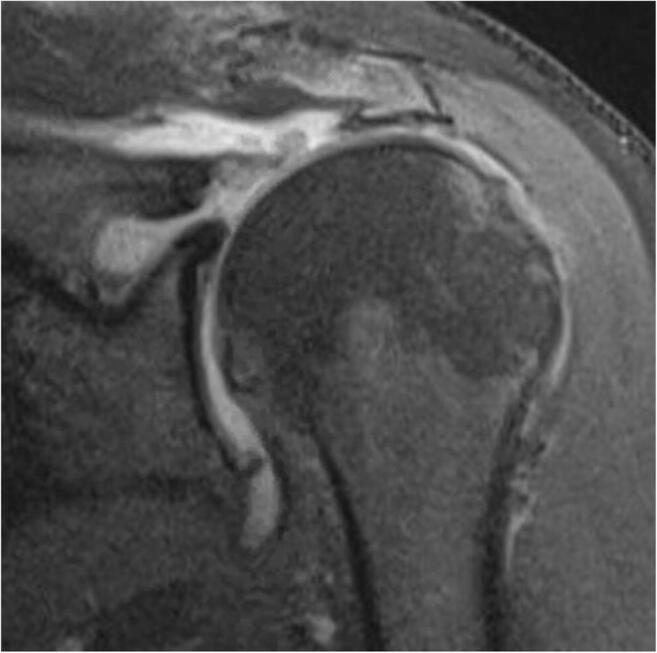

Fig. 2.

Tendon retraction. A coronal T2 view on an MRI shows tendon retraction to the level of the glenoid, Patte Grade 3 [2]

Treatment of Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears

Nonoperative Treatment

Although it is very reasonable to try nonoperative measures, such as physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and corticosteroid injections in patients who wish to avoid surgery, there is no evidence to support that these or other nonoperative treatment modalities alter the natural history of massive rotator cuff tears [2, 3, 65]. Nonetheless, most surgeons would recommend at least 3–6 months of these nonoperative measures prior to considering a reconstructive surgical intervention.

Surgical Options for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears

There are many options for surgeons when treating FIRCTs without arthritis, including partial repair [15, 66], augmentation or bridging with allografts [17–22], superior capsular reconstruction [23–26], subacromial balloon [27], reverse shoulder arthroplasty [40–43], and tendon transfers including the latissimus dorsi [28–36, 67] and lower trapezius transfer [37, 38, 44]. The results of partial repair [15] deteriorate with time, while the reported outcomes of graft augmentation and superior capsular reconstruction are limited to relatively small case series with short-term follow-up. Alternatively, the reverse shoulder arthroplasty, originally introduced for the treatment of massive rotator cuff tears by Paul Grammont [41•], provides very reproducible results for FIRCTs [40–43]. However, this joint replacement procedure has been associated with complications [42, 68] and functional limitations [69, 70] in certain patient populations.

Tendon Transfers for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears

Over the last 30 years, tendon transfers have been proven to be able to reliably restore shoulder function and decrease associated pain in patients with posterosuperior FIRCTs [28–38]. This is likely the result of their ability to dynamically restore the shoulder’s anterior-posterior force couple. Transfer of a dynamic stabilizer that can be trained to be synergistic to the torn tendon and non-functional muscle may balance the shoulder and restore the patient’s force couple. These transfers contribute directly to external rotation and abduction while stabilizing the pathologic translation of the humeral head. Whenever planning to perform a tendon transfer, there are a few important principles to follow [71, 72]:

Similar excursion between transferred and recipient muscle.

Expendable transferred muscle without compromising shoulder function.

Similar line of pull between the transferred tendon and the recipient muscle.

Each tendon transferred should replace only 1 function of the recipient.

The open LDT has historically been the most studied transfer for posterosuperior FIRCT, with good clinical and radiographic outcomes reported for the past 10 years of follow-up [73]. However, some medium- to long-term studies have reported difficulty for patients retraining their transferred tendon [34•] and associated poor long-term outcomes [67]. Although the technique has been modified to be performed in an arthroscopic-assisted fashion, the studies examining this technique are limited to short-term follow-up case series [28, 30, 31].

The LTT has certain biomechanical and functional advantages that potentially overcome some of the limitations of the LDT, including an “in-line” transfer with a more favorable line of pull and an “in-phase” transfer that is easier for patients to retrain. Furthermore, once mastered, the harvest of the lower trapezius is potentially technically easier and faster than the latissimus dorsi.

Lower Trapezius Transfer

Indications

The LTT was initially described as a reliable method of restoring shoulder external rotation in patients with brachial plexus injuries [74]. Currently, its indications have been expanded to functionally irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears, included prior failed rotator cuff repairs. Although the initial results have been promising in this patient population [37, 38], its success depends on proper patient selection (Table 1). Unlike the LDT [33, 34, 36, 73], the LTT has shown promising outcomes for patients with teres minor and subscapularis pathology, as well as those with pseudoparalysis [37, 38]. The following are the three of the most important considerations regarding LTT:

Intact or reparable subscapularis without dynamic anterosuperior escape: Given that this transfer acts dynamically to restore the posterior aspect of the force couple, it is critical to have the anterior aspect of the force couple intact or reparable.

Absence of rotator cuff arthropathy or advanced glenohumeral arthritis: Hamada [75] Grade 3 or higher with associated acetabularization of the acromion or femoralization of the humerus cannot be properly addressed by a joint preserving procedure.

Healthy deltoid: After restoring the force couple with a LTT, the deltoid will provide most of the power for active elevation. In the absence of a functioning deltoid, LTT may still be able restore external rotation, but naturally will not improve abduction or elevation.

Table 1.

Contraindications to lower trapezius transfer

| Indicated if goal only external rotation* | Relative contraindications | Absolute contraindications |

|---|---|---|

| Deltoid paralysis | Advanced age (> 70–75 years) | Rotator cuff arthropathy grade 3 or higher [4] |

| Brachial plexus injury | Dynamic anterosuperior escape (± irreparable subscapularis) | Advanced glenohumeral arthritis |

| Poor bone quality | Infection | |

| Poor compliance | Paralyzed trapezius muscle |

*In the setting of deltoid paralysis or an irreparable subscapularis tear, the lower trapezius can still restore external rotation, but is not as effective at restoring abduction or elevation

Anatomy and Biomechanics

The lower trapezius tendon is one of the three parts of the trapezius muscle, functioning to stabilize the scapula and provide scapular external rotation [76]. It inserts on the medial aspect of the scapular spine, and it is innervated by the spinal accessory nerve, which travels medial to the medial angle of the scapula.

When comparing the LDT and LTT procedures, three biomechanical and anatomic advantages may favor LTT:

“In-line”: The lower trapezius tendon attached mimics the vector of the infraspinatus tendon (Fig. 3).

Moment arm: Recent biomechanical studies have found the LTT to have better abduction and external rotation moment arms compared with LDT [77–79].

“In-phase”: The lower trapezius muscle is activated in the native shoulder during external rotation, elevation, and abduction [80]. This makes it potentially easier for patients to retrain their LTT transfer. On the contrary, the latissimus dorsi tendon function in the native shoulder is adduction and internal rotation.

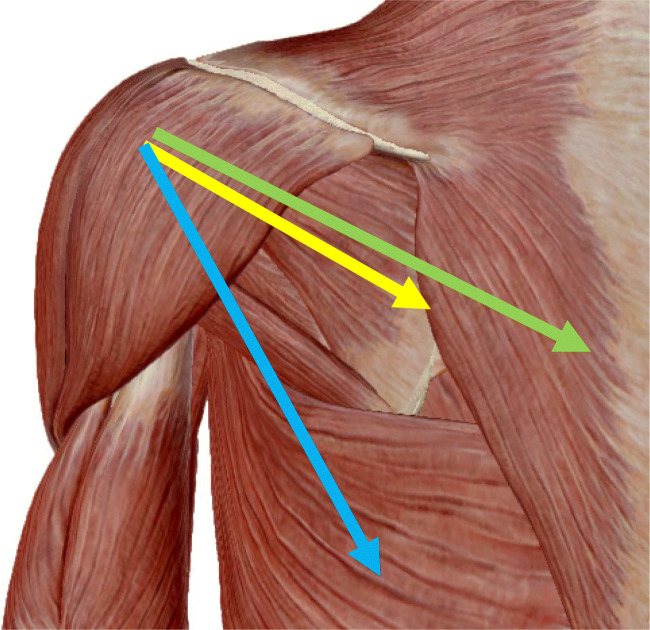

Fig. 3.

Line of pull. The line of pull of the infraspinatus (yellow arrow) is more similar to the lower trapezius (green arrow) than the latissimus dorsi (blue arrow)

Surgical Technique for Arthroscopically Assisted LTT

Although initially described as an open technique [37••], in recent years LTT has been modified to a less invasive arthroscopic-assisted technique [35, 38, 44, 81], avoiding the need to perform deltoid take-down or an acromial osteotomy or to perform the transfer. This avoids the potential danger of deltoid insufficiency, allows arthroscopic visualization of the passage between the deltoid and infraspinatus fascia, and has the potential to lead to less subacromial adhesions.

The arthroscopic-assisted LTT is performed in the beach chair position, with adequate draping of the surgical field beyond the medial aspect of the scapula [35, 44, 81]. We prefer to perform the tendon harvest prior to the arthroscopic portion in most cases. It is helpful to accurately draw out all the surface landmarks for both the tendon harvest and the arthroscopic portions of the transfer: the scapular spine and body, lower trapezius course (origin from mid-thoracic to T12; insertion on medial 3–5 cm of scapular spine), acromion, and coracoid. For tendon harvest, we have modified the previous technique [44•] to now use a horizontal incision just inferior to the scapular spine, from 4 cm lateral to the medial edge to 1 cm medial to the medial edge (Fig. 4). Prior to identifying the tendon, it is critical to excise out overlying adipose tissue. The lower trapezius tendon is then identified with the help of the fat triangle near the tendon insertion and the inferior muscle belly traveling diagonally up to the scapular spine. If the surgeon is having difficulty identifying this tendon, the bone “axilla” of the medial angle of the scapular spine can be used to identify the tendon running over the top of it (Fig. 5). It is critical to define the undersurface of the tendon/muscle, separating it from the underlying infraspinatus fascia. The tendon is then followed diagonally up to its insertion on the scapular spine and detached with electrocautery, mobilizing the lower trapezius from the infraspinatus fascia and middle trapezius. The lower and middle trapezius muscle bellies can be separated by following the horizontal part of the triangular tendinous insertion of the lower trapezius horizontally towards the mid-thoracic spine. Superficial dissection is very safe, but deep dissection medial to the medial scapular border beyond 2 cm should be avoided to protect the spinal accessory nerve in the deep fascia of the muscle. The tendon is then prepared to receive a #2 non-absorbable in a Krakow fashion to assist with mobilization (Fig. 6).

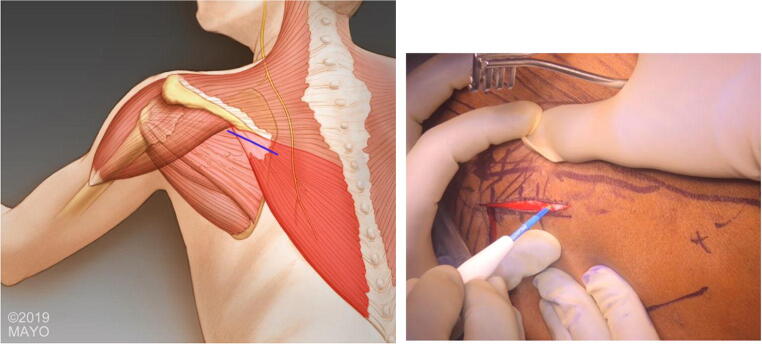

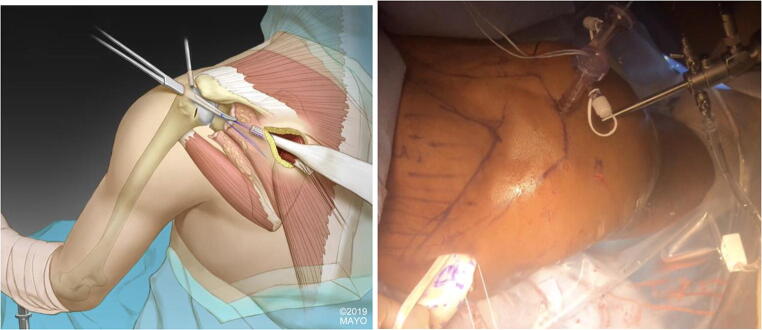

Fig. 4.

Incision. The landmarks are mapped out, and a horizontal incision is utilized just inferior to the scapular spine, from 4 cm lateral to the medial edge to 1 cm medial to the medial edge

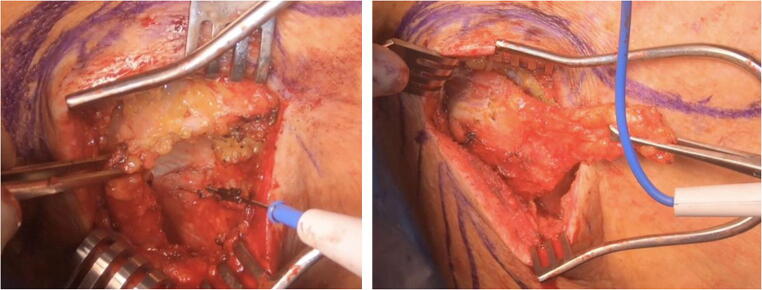

Fig. 5.

Harvest. The “axilla” of the medial angle of the scapular spine can be used to identify the tendon, as well as the underlying infraspinatus fascia. The tendon then should be properly mobilized for superficial adhesions

Fig. 6.

Tendon preparation. The lower trapezius tendon is seen on the deep surface of the muscle and is prepared with a running Krackow suture to create a “bulls-eye” for the future Pulvertaft weave

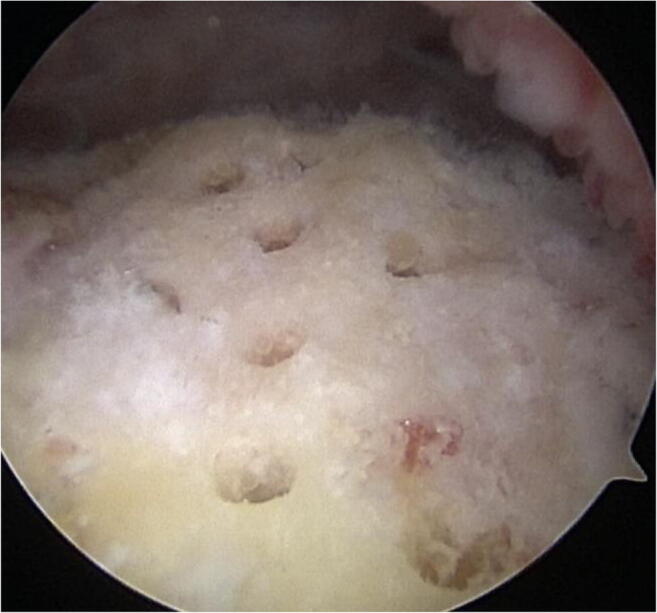

To perform the arthroscopic portion, we utilize the lateral portal as the primary visualization portal and the anterior, medial, and anterolateral portals as working portals. After performing a diagnostic arthroscopy and subacromial decompression if needed, the irreparable portions of the rotator cuff are debrided, and any previous anchors or sutures are removed. The infraspinatus is prepared for a partial repair if possible. The subscapularis should also be repaired if necessary, prior to performing the transfer. If needed, a biceps tenodesis should also be performed prior to securing the graft. Then, the greater tuberosity is prepared to facilitate bone healing [82] (Fig. 7). If an infraspinatus repair is possible, this is performed prior to performing the transfer. Once ready for the transfer, the interval is developed between the infraspinatus superficial fascia and the deltoid muscle.

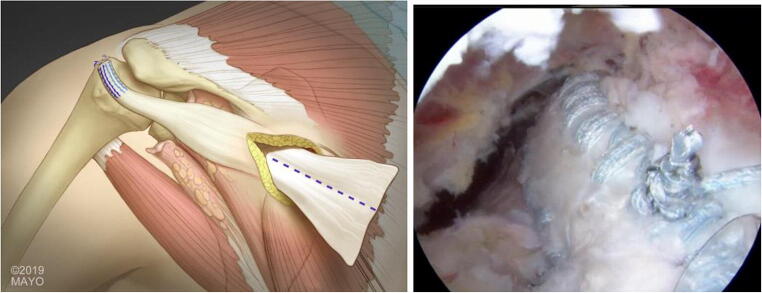

Fig. 7.

Footprint preparation. The greater tuberosity is prepared utilizing the “crimson duvet” technique to facilitate bone healing [3]

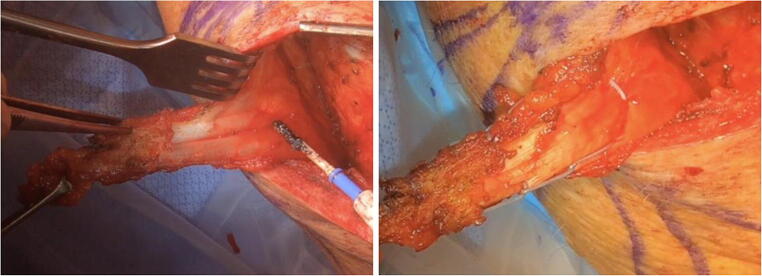

Switching back to the medial scapular incision, the infraspinatus fascia is incised along the lines of the muscle fibers to allow passage of the transferred tendon. Prior to the transfer, an Achilles allograft is prepared with two Krakow sutures and an overlapping baseball stitch on the narrower side of the graft (Fig. 8). A long arthroscopic grasper is then placed through the anterolateral portal out the medial incision to grasp the sutures attached to the allograft (Fig. 9). The sutures are then retrieved out the anterolateral portal. Suture management is key at this step to avoid any twists or knots in the sutures prior to placing the anchors.

Fig. 8.

Allograft preparation. The allograft is prepared with multiple Krackow sutures of different colors

Fig. 9.

Tendon transfer. A hip arthroscopy grasper is then placed through the anterolateral portal out the medial incision to grasp the sutures attached to the allograft

The allograft is then anchored into the tuberosity, using an anteromedial anchor just lateral to the articular surface and posterior to the bicipital groove, as well as an anterolateral anchor just off the ledge of the greater tuberosity, posterior to the bicipital groove (Fig. 10). Accessory medial and lateral sutures can be placed if desired for further footprint coverage. After fixing the allograft, multiple cycles of shoulder internal and external rotation are performed to increase the final tension of the allograft (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10.

Anchor placement. The anteromedial anchor (red circle) is placed just lateral to the articular surface and posterior to the bicipital groove (yellow oval), while the anterolateral anchor (blue circle) is placed just distal to the greater tuberosity footprint and posterior to the bicipital groove

Fig. 11.

Tendon orientation. The allograft is anchored in place to the tuberosity with 2 main and 2 accessory anchors for maximal footprint coverage, then splint in the medial incision for the pulvertaft weave

Attention is then directed back to the medial scapular incision. It is critical to place the arm in maximal external rotation in 60°–90° of abduction at this step. The allograft tendon is then split and secured to the lower trapezius using a Pulvertaft weave technique in maximal tension with multiple sutures (Fig. 12). Vancomycin powder is then placed, and the incision is closed in layered fashion prior to placing the patient in the external rotation immobilizer. The postoperative therapy protocol is summarized in Table 2.

Fig. 12.

Pulvertaft weave. The allograft is split, and Pulvertaft weave is performed to secure to the lower trapezius tendon, anchoring with multiple figure eight sutures in maximal possible tension

Table 2.

Postoperative therapy protocol

| Postoperative time point | Activity |

|---|---|

| 0 to 6–8 weeks | Custom external rotation brace, with shoulder maintained in 30°–40° abduction and 30°–40° of external rotation |

| 6–8 to 12 weeks | Progression from passive to active-assisted to active shoulder motion with an internal rotation limit to neutral (0°). Pool-based exercises are started |

| 12 to 16 weeks | Removal of internal rotation limit. Return to most activities of daily living. Pool-based exercises are continued |

| 16 weeks to 6 months | Strengthening without limits on motion, focusing on the scapula motion as well as internal/external rotation, abduction |

| 4–6 months | Return to full unrestricted activities |

Tips and Tricks

Tips and tricks for this procedure can be found in Table 3. These are a few critical steps to perform this surgery and maximize the possibility of a successful outcome:

Harvest (Fig. 5): It is critical to excise out the overlying fat and use reliable landmarks (e.g., “axilla” of medial scapula) to identify the tendon. Furthermore, in the infero-lateral aspect of the incision is the infraspinatus fascia, which can also help to identify the muscle belly. The tendon inserts on to the scapular spine posteriorly to the posterior deltoid, which can also be used as a landmark.

Tendon mobilization (Fig. 6): It is important to release adhesions of the lower trapezius to the skin, release the superficial fascia between the middle and lower trapezius, and release the adhesions to the medial border of the scapula. The tendon should be able to almost reach the posterior portal of the arthroscopy.

Allograft preparation (Fig. 8): The graft should be prepared either preoperatively or simultaneously during the procedure with 2–4 sutures to be anchored for maximal footprint compression.

Simultaneous procedures: It is important to perform an adequate subscapularis and infraspinatus repair, when needed and possible, prior to performing the transfer. Biceps tenotomy or tenodesis can also be helpful to better visualize the optimal anchor placement.

Anchor positions (Fig. 10): It is imperative to place the anteromedial anchor just lateral to the articular surface and posterior to the bicipital groove, while the anterolateral anchor should be placed just distal to the greater tuberosity footprint and posterior to the bicipital groove.

Graft-tendon weave (Fig. 12): It is critical to place the arm in maximal external rotation and 60°–90° of abduction and to pull the maximal tension on the graft and tendon to achieve as tight of a weave as possible. It is almost impossible to overtension the reconstruction during step.

Postoperative (Table 2): The patient must keep the arm in an external rotation immobilizer for 6–8 weeks and then cannot be permitted to do any internal rotation activities past neutral (0 degrees) for 12 weeks to avoid stretching the graft.

Table 3.

Tips and tricks

| Step | Tip |

|---|---|

| Harvest | Excise fat overlying tendon and infraspinatus fascia |

| Landmarks | Use the “axilla” of the medial scapula, posterior deltoid, and underlying infraspinatus fascia as landmarks when identifying tendon |

| Lower vs middle | Separate lower trapezius from middle trapezius by following the triangle of underlying tendon, curving diagonally off the medial angle of the scapula |

| Mobilization | Release the superficial adhesions, adhesions to the medial angle of the scapula, and superficial fascia between lower and middle trapezius |

| Dangers | Avoid deep dissection medial to the medial border of the scapula to protect the neurovascular bundle |

| Concomitant procedures | Perform a tension-free subscapularis repair first, and then perform an infraspinatus repair if possible. By performing a biceps tenodesis after opening the groove, it can help with anchor placement |

| Footprint preparation | We prefer to use the crimson duvet technique to maximize graft-bone incorporation |

| Graft transfer | Use a hip arthroscopy grasper to bring sutures from graft into joint. Organize the sutures prior to pulling the graft into the joint |

| Anchor placement | Place the anteromedial anchor near the “L” made by the bicipital groove and the articular surface. Place the anterolateral anchor just off the tuberosity |

| Accessory anchors | Place accessory anchors medial or lateral to maximize footprint compression |

| Graft-tendon tension | Place the arm in maximal external rotation and 60°–90° of abduction, and pull maximal tension on the graft and tendon to achieve as tight of a weave as possible. Cannot overtension |

| Postoperative | Maintain external rotation immobilizer for 6–8 weeks; then no passive internal rotation until 12 weeks |

Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes

Historically, the primary tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears has been the latissimus dorsi transfer (LDT). Since its initial description by Gerber et al. in 1998 [83], both the open technique [32, 72, 83–85] and more recently the arthroscopic-assisted technique [28, 31, 86–89] have been reported to provide good shoulder pain relief and functional improvements. Several factors seem to be associated with a worse outcome after this LDT, including prior rotator cuff repair [33, 36, 86, 90], pseudoparalysis [34, 86], poor subscapularis [33, 73, 90] or teres minor [36, 73] function, and critical shoulder angle > 35° [73]. For example, one biomechanical study showed that the external rotation and abduction forces after LDT are dependent on the counterbalancing forces of the subscapularis [91]. With subscapularis insufficiency, the humeral head translates anteriorly and inferiorly after the LDT. Additionally, Iannotti et al. found that patients with poor outcomes after LDT lacked synchronous, in-phase contraction of the “out of phase” latissimus dorsi [34].

Alternatively, the “in-phase” and “in-line” LTT theoretically overcomes many of these shortcomings. Since its original description by Elhassan et al. [74•] in 2009, it has been reported to successfully restore external rotation in the paralytic shoulder [72, 92, 93]. The ease and success with which patients are able to retrain their shoulder after the transfer is in part due to its “in-phase” contraction with the native shoulder external rotators and abductors [80], a similar excursion when compared with the infraspinatus [94], and “in-line” pull that simulates the infraspinatus vector (Fig. 2). In a study on the open LTT for FIRCTs, 33 patients followed for a mean of 47 months experienced good pain relief, improvements in external rotation and abduction, as well as patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [37••]. Outcomes were better in patients with preoperative elevation over 60°.

We prefer to perform this technique via the arthroscopic-assisted technique [35, 44]. Valenti et al. reported on 14 patients with external rotation lag and Hornblower’s signs who underwent LTT augmented with a semitendinosus autograft [38••]. At a mean follow-up of 24 months, patients improved their PROMs and pain scores by more than double, with only 1 revision procedure secondary to an infection and no graft tears. The two authors in this article have published [81••] on the largest series to date of arthroscopic-assisted LTT. Forty-one patients underwent the arthroscopic-assisted LTT, including 66% with a failed prior rotator cuff repair. Overall, 37 (90%) had excellent outcomes with improvements in all PROMs, shoulder function, and pain scores. Improved functional outcomes were seen in patients with shoulder flexion more than 60° and < 2 years’ time interval between symptoms and presentation for treatment. There were 4 (10%) failures, with an increased risk in those with advanced Hamada grades for rotator cuff arthropathy. Subscapularis or teres minor pathology, as well as pseudoparalysis, did not seem to impact the ultimate outcomes.

Conclusions

Transfer of the lower trapezius to the greater tuberosity represents a promising option to treat patients with functionally irreparable rotator cuff tears. Advances in surgical technique now allow this transfer to be performed arthroscopically assisted, potentially improving patient recovery and early functional gains. When considering the ideal tendon transfer for the management of FIRCTs, it is critical to consider classic tendon transfer principles, as well as the ability of the patients to retrain the new transfer to perform a different function. For the LTT, improved outcomes are particularly seen in patients with shoulder flexion more than 60 degrees, minimal to no arthritis of the shoulder, and < 2 years’ time interval between symptoms and presentation for treatment. Potential advantages for this tendon transfer include a similar excursion and “in-line” pull to the infraspinatus tendon, “in-phase” contraction with external rotation and abduction, less humeral head depression if subscapularis insufficiency, and minimally invasive approach avoiding an acromial osteotomy. However, the LTT is relatively new, and as such long-term outcomes studies are lacking; in addition, the LTT is an indirect transfer and thus potentially subjects to failure mechanisms associated with allograft failure. Future comparative trials with large patient numbers and longer follow-up are needed to better understand the indications for each of these transfers to treat these difficult pathologies.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Eric Wagner receives consulting fees from Stryker and research support from Arthrex, Konica Minolta, and DJO. None are relevant to this manuscript.

Bassem Elhassan receives consulting fees from Arthrex, DJO, and Integra.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Surgical Management of Massive Irreparable Cuff Tears

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Eric R. Wagner, Email: Eric.r.wagner@emory.edu

Bassem T. Elhassan, Email: Elhassan.bassem@mayo.edu

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.• Goutallier D, Postel JM, Bernageau J, Lavau L, Voisin MC. Fatty muscle degeneration in cuff ruptures. Pre- and postoperative evaluation by CT scan. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1994;30E4:78–83 Demonstrated the fatty infiltration classification. [PubMed]

- 2.Melis B, Wall B, Walch G. Natural history of infraspinatus fatty infiltration in rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(5):757–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moosmayer S, Gartner AV, Tariq R. The natural course of nonoperatively treated rotator cuff tears: an 8.8-year follow-up of tear anatomy and clinical outcome in 49 patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(4):627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galatz LM, Connor PM, Calfee RP, Hsu JC, Yamaguchi K. Pectoralis major transfer for anterior-superior subluxation in massive rotator cuff insufficiency. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2003;12(1):1–5. doi: 10.1067/mse.2003.128137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavriilidis I, Kircher J, Magosch P, Lichtenberg S, Habermeyer P. Pectoralis major transfer for the treatment of irreparable anterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Int Orthop. 2010;34(5):689–694. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0799-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warner JJ, Higgins L, Parsons IM, Dowdy P. Diagnosis and treatment of anterosuperior rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2001;10(1):37–46. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.112022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wirth MA, Rockwood CA., Jr Operative treatment of irreparable rupture of the subscapularis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(5):722–731. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199705000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedi A, Dines J, Warren RF, Dines DM. Massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(9):1894–1908. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harryman DT, 2nd, Mack LA, Wang KY, Jackins SE, Richardson ML, Matsen FA., 3rd Repairs of the rotator cuff. Correlation of functional results with integrity of the cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(7):982–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henry P, Wasserstein D, Park S, Dwyer T, Chahal J, Slobogean G, Schemitsch E. Arthroscopic repair for chronic massive rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(12):2472–2480. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galatz LM, Ball CM, Teefey SA, Middleton WD, Yamaguchi K. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(2):219–224. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen KH, Chiang ER, Wang HY, Ma HL. Arthroscopic partial repair of irreparable rotator cuff tears: factors related to greater degree of clinical improvement at 2 years of follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Denard PJ, Jiwani AZ, Ladermann A, Burkhart SS. Long-term outcome of arthroscopic massive rotator cuff repair: the importance of double-row fixation. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SJ, Lee IS, Kim SH, Lee WY, Chun YM. Arthroscopic partial repair of irreparable large to massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shon MS, Koh KH, Lim TK, Kim WJ, Kim KC, Yoo JC. Arthroscopic partial repair of irreparable rotator cuff tears: preoperative factors associated with outcome deterioration over 2 years. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(8):1965–1975. doi: 10.1177/0363546515585122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boileau P, Baque F, Valerio L, Ahrens P, Chuinard C, Trojani C. Isolated arthroscopic biceps tenotomy or tenodesis improves symptoms in patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):747–757. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barber FA, Burns JP, Deutsch A, Labbe MR, Litchfield RB. A prospective, randomized evaluation of acellular human dermal matrix augmentation for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciampi P, Scotti C, Nonis A, Vitali M, Di Serio C, Peretti GM, et al. The benefit of synthetic versus biological patch augmentation in the repair of posterosuperior massive rotator cuff tears: a 3-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1169–1175. doi: 10.1177/0363546514525592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferguson DP, Lewington MR, Smith TD, Wong IH. Graft utilization in the augmentation of large-to-massive rotator cuff repairs: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(11):2984–2992. doi: 10.1177/0363546515624463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lederman ES, Toth AP, Nicholson GP, Nowinski RJ, Bal GK, Williams GR, Iannotti JP. A prospective, multicenter study to evaluate clinical and radiographic outcomes in primary rotator cuff repair reinforced with a xenograft dermal matrix. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2016;25(12):1961–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ono Y, Davalos Herrera DA, Woodmass JM, Boorman RS, Thornton GM, Lo IK. Graft augmentation versus bridging for large to massive rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2017;33(3):673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinhaus ME, Makhni EC, Cole BJ, Romeo AA, Verma NN. Outcomes after patch use in rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(8):1676–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denard PJ, Brady PC, Adams CR, Tokish JM, Burkhart SS. Preliminary results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction with dermal allograft. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(1):93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.08.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, Fukunishi K, Ohue M, Tsujimura T, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pennington WT, Bartz BA, Pauli JM, Walker CE, Schmidt W. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction with acellular dermal allograft for the treatment of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: short-term clinical outcomes and the radiographic parameter of superior capsular distance. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(6):1764–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodmass JM, Wagner ER, Borque KA, Chang MJ, Welp KM, Warner JJP. Superior capsule reconstruction using dermal allograft: early outcomes and survival. J shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28(6S):S100–S1S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricci M, Vecchini E, Micheloni GM, Berti M, Schenal G, Zanetti G, et al. A clinical and radiological study of biodegradable subacromial spacer in the treatment of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Acta Biomed. 2017;88(4 -S):75–80. doi: 10.23750/abm.v88i4-S.6797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castricini R, Longo UG, De Benedetto M, Loppini M, Zini R, Maffulli N, et al. Arthroscopic-assisted latissimus dorsi transfer for the management of irreparable rotator cuff tears: short-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(14):e119. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein Y, Grimberg J, Valenti P, Chechik O, Drexler M, Kany J. Arthroscopic fixation with a minimally invasive axillary approach for latissimus dorsi transfer using an endobutton in massive and irreparable postero-superior cuff tears. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2013;7(2):79–82. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.114223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kany J, Selim HA. Combined fully arthroscopic transfer of latissimus dorsi and teres major for treatment of irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Arthrosc Tech. 2020;9(1):e147–ee57. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villacis D, Merriman J, Wong K, Rick Hatch GF., III Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a modified technique using arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(1):e27–e30. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerber C. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable tears of the rotator cuff. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:152–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerber C, Maquieira G, Espinosa N. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(1):113–120. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iannotti JP, Hennigan S, Herzog R, Kella S, Kelley M, Leggin B, et al. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Factors affecting outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(2):342–348. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner ER, Woodmass JM, Welp KM, Chang MJ, Elhassan BT, Higgins LD, et al. Novel arthroscopic tendon transfers for posterosuperior rotator cuff tears: latissimus dorsi and lower trapezius transfers. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2018;8(2):e12. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.ST.17.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warner JJ, Parsons IM. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer: a comparative analysis of primary and salvage reconstruction of massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2001;10(6):514–521. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.118629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elhassan BT, Wagner ER, Werthel JD. Outcome of lower trapezius transfer to reconstruct massive irreparable posterior-superior rotator cuff tear. J shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(8):1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valenti P, Werthel JD. Lower trapezius transfer with semitendinosus tendon augmentation: indication, technique, results. Obere Extrem. 2018;13(4):261–268. doi: 10.1007/s11678-018-0495-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elhassan BT, Wagner ER, Kany J. Latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable subscapularis tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surgery / Am Shoulder Elbow Surgeons [et al]. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Boileau P, Watkinson D, Hatzidakis AM, Hovorka I. Neer award 2005: the Grammont reverse shoulder prosthesis: results in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):527–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grammont PM, Baulot E. Delta shoulder prosthesis for rotator cuff rupture. Orthopedics. 1993;16(1):65–68. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19930101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartzler RU, Steen BM, Hussey MM, Cusick MC, Cottrell BJ, Clark RE, Frankle MA. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for massive rotator cuff tear: risk factors for poor functional improvement. J shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(11):1698–1706. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mulieri P, Dunning P, Klein S, Pupello D, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tear without glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(15):2544–2556. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elhassan BT, Alentorn-Geli E, Assenmacher AT, Wagner ER. Arthroscopic-assisted lower trapezius tendon transfer for massive irreparable posterior-superior rotator cuff tears: surgical technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(5):e981–e9e8. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clement ND, Hallett A, MacDonald D, Howie C, McBirnie J. Does diabetes affect outcome after arthroscopic repair of the rotator cuff? J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92(8):1112–1117. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B8.23571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fermont AJ, Wolterbeek N, Wessel RN, Baeyens JP, de Bie RA. Prognostic factors for successful recovery after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a systematic literature review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(3):153–163. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2014.4832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almeida A, Valin MR, Zampieri R, Almeida NC, Roveda G, Agostini AP. Comparative analysis on the result for arthroscopic rotator cuff suture between smoking and non-smoking patients. Rev Bras Ortop. 2011;46(2):172–175. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diebold G, Lam P, Walton J, Murrell GAC. Relationship between age and rotator cuff retear: a study of 1,600 consecutive rotator cuff repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(14):1198–1205. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lim SJ, Sun JH, Kekatpure AL, Chun JM, Jeon IH. Rotator cuff surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: clinical outcome comparable to age, sex and tear size matched non-rheumatoid patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99(7):579–583. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2017.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen X, Giambini H, Ben-Abraham E, An KN, Nassr A, Zhao C. Effect of bone mineral density on rotator cuff tear: an osteoporotic rabbit model. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, Mattila KT, Tuominen EK, Kauko T, et al. Treatment of non-traumatic rotator cuff tears: a randomised controlled trial with one-year clinical results. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(1):75–81. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B1.32168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castoldi F, Blonna D, Hertel R. External rotation lag sign revisited: accuracy for diagnosis of full thickness supraspinatus tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meyer DC, Farshad M, Amacker NA, Gerber C, Wieser K. Quantitative analysis of muscle and tendon retraction in chronic rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):606–610. doi: 10.1177/0363546511429778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zingg PO, Jost B, Sukthankar A, Buhler M, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C. Clinical and structural outcomes of nonoperative management of massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(9):1928–1934. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeong JY, Song SY, Yoo JC, Park KM, Lee SM. Comparison of outcomes with arthroscopic repair of acute-on-chronic within 6 months and chronic rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(4):648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duncan NS, Booker SJ, Gooding BW, Geoghegan J, Wallace WA, Manning PA. Surgery within 6 months of an acute rotator cuff tear significantly improves outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(12):1876–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goutallier DBJ, Patte D. Assessment of the trophicity of the muscles of the ruptured rotator cuff by CT scan. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1989;75:126–127. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fuchs B, Weishaupt D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Gerber C. Fatty degeneration of the muscles of the rotator cuff: assessment by computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8(6):599–605. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(99)90097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meyer DC, Wieser K, Farshad M, Gerber C. Retraction of supraspinatus muscle and tendon as predictors of success of rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2242–2247. doi: 10.1177/0363546512457587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patte D. Classification of rotator cuff lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim JY, Park JS, Rhee YG. Can preoperative magnetic resonance imaging predict the reparability of massive rotator cuff tears? Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(7):1654–1663. doi: 10.1177/0363546517694160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Labriola JE, Lee TQ, Debski RE, McMahon PJ. Stability and instability of the glenohumeral joint: the role of shoulder muscles. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2005;14(1 Suppl S):32S–38S. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burkhart SS. Arthroscopic treatment of massive rotator cuff tears. Clinical results and biomechanical rationale. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;267:45–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mihata T, McGarry MH, Kahn T, Goldberg I, Neo M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical role of capsular continuity in superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable tears of the supraspinatus tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1423–1430. doi: 10.1177/0363546516631751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Melis B, DeFranco MJ, Chuinard C, Walch G. Natural history of fatty infiltration and atrophy of the supraspinatus muscle in rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(6):1498–1505. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1207-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burkhart SS, Nottage WM, Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Kohn HS, Pachelli A. Partial repair of irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(4):363–370. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(05)80186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muench LN, Kia C, Williams AA, Avery DM, 3rd, Cote MP, Reed N, et al. High clinical failure rate after latissimus dorsi transfer for revision massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2020;36(1):88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagner ER, Houdek MT, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Cofield R, et al. The role age plays in the outcomes and complications of shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(9):1573–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bacle G, Nove-Josserand L, Garaud P, Walch G. Long-term outcomes of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a follow-up of a previous study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(6):454–461. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garcia GH, Taylor SA, DePalma BJ, Mahony GT, Grawe BM, Nguyen J, et al. Patient activity levels after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: what are patients doing? Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(11):2816–2821. doi: 10.1177/0363546515597673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brand PW, Beach RB, Thompson DE. Relative tension and potential excursion of muscles in the forearm and hand. J Hand Surg. 1981;6(3):209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(81)80072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Elhassan B, Bishop A, Shin A, Spinner R. Shoulder tendon transfer options for adult patients with brachial plexus injury. J Hand Surg [Am] 2010;35(7):1211–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gerber C, Rahm SA, Catanzaro S, Farshad M, Moor BK. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for treatment of irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears: long-term results at a minimum follow-up of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1920–1926. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Elhassan B, Bishop A, Shin A. Trapezius transfer to restore external rotation in a patient with a brachial plexus injury. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(4):939–944. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobayashi Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kibler WB, Sciascia A, Wilkes T. Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder injury. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(6):364–372. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-06-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hartzler RU, Barlow JD, An KN, Elhassan BT. Biomechanical effectiveness of different types of tendon transfers to the shoulder for external rotation. J shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1370–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Omid R, Heckmann N, Wang L, McGarry MH, Vangsness CT, Jr, Lee TQ. Biomechanical comparison between the trapezius transfer and latissimus transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(10):1635–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reddy A, Gulotta LV, Chen X, Castagna A, Dines DM, Warren RF, Kontaxis A. Biomechanics of lower trapezius and latissimus dorsi transfers in rotator cuff-deficient shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28(7):1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith J, Padgett DJ, Dahm DL, Kaufman KR, Harrington SP, Morrow DA, Irby SE. Electromyographic activity in the immobilized shoulder girdle musculature during contralateral upper limb movements. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2004;13(6):583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.•• Elhassan BT, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Wagner ER. Outcome of arthroscopically assisted lower trapezius transfer to reconstruct massive irreparable posterior-superior rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg / Am Shoulder Elbow Surgeons [et al]. 2020. Largest study to date on the lower trapezius arthroscopic assisted technique. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Nakagawa H, Morihara T, Fujiwara H, Kabuto Y, Sukenari T, Kida Y, Furukawa R, Arai Y, Matsuda KI, Kawata M, Tanaka M, Kubo T. Effect of footprint preparation on tendon-to-bone healing: a histologic and biomechanical study in a rat rotator cuff repair model. Arthroscopy. 2017;33(8):1482–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gerber C, Vinh TS, Hertel R, Hess CW. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;232:51–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Waters PM. Update on management of pediatric brachial plexus palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(1):116–126. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200501000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moursy M, Forstner R, Koller H, Resch H, Tauber M. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a modified technique to improve tendon transfer integrity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(8):1924–1931. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Castricini R, De Benedetto M, Familiari F, De Gori M, De Nardo P, Orlando N, et al. Functional status and failed rotator cuff repair predict outcomes after arthroscopic-assisted latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable massive rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2016;25(4):658–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Grimberg J, Kany J, Valenti P, Amaravathi R, Ramalingam AT. Arthroscopic-assisted latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(4):599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jermolajevas V, Kordasiewicz B. Arthroscopically assisted latissimus dorsi tendon transfer in beach-chair position. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(4):e359–e363. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yamakado K. Clinical and radiographic outcomes with assessment of the learning curve in arthroscopically assisted latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90.Namdari S, Voleti P, Baldwin K, Glaser D, Huffman GR. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(10):891–898. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Werner CM, Zingg PO, Lie D, Jacob HA, Gerber C. The biomechanical role of the subscapularis in latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(6):736–742. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Elhassan B, Bishop AT, Hartzler RU, Shin AY, Spinner RJ. Tendon transfer options about the shoulder in patients with brachial plexus injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(15):1391–1398. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Elhassan B. Lower trapezius transfer for shoulder external rotation in patients with paralytic shoulder. J Hand Surg. 2014;39(3):556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Herzberg G, Urien JP, Dimnet J. Potential excursion and relative tension of muscles in the shoulder girdle: relevance to tendon transfers. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1999;8(5):430–437. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(99)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]