Abstract

Evidence from past economic crises indicates that recessions often affect men’s and women’s employment differently, with a greater impact on male-dominated sectors. The current COVID-19 crisis presents novel characteristics that have affected economic, health and social phenomena over wide swaths of the economy. Social distancing measures to combat the spread of the virus, such as working from home and school closures, have placed an additional tremendous burden on families. Using new survey data collected in April 2020 from a representative sample of Italian women, we analyse the effects of working arrangements due to COVID-19 on housework, childcare and home schooling among couples where both partners work. Our results show that most of the additional housework and childcare associated to COVID-19 falls on women while childcare activities are more equally shared within the couple than housework activities. According to our empirical estimates, changes to the amount of housework done by women during the emergency do not seem to depend on their partners’ working arrangements. With the exception of those continuing to work at their usual place of work, all of the women surveyed spend more time on housework than before. In contrast, the amount of time men devote to housework does depend on their partners’ working arrangements: men whose partners continue to work at their usual workplace spend more time on housework than before. The link between time devoted to childcare and working arrangements is more symmetric, with higher percentages of both women and men spending less time with their children if they continue to work away from home. For home schooling, too, parents who continue to go to their usual workplace after the lockdown are less likely to spend greater amounts of time with their children than before. Similar results emerge for the partners of women not working before the emergency. Finally, analysis of work–life balance satisfaction shows that working women with children aged 0–5 are those who find balancing work and family more difficult during COVID-19. The work–life balance is especially difficult to achieve for those with partners who continue to work outside the home during the emergency.

Keywords: COVID-19, Work arrangements, Housework, Childcare

Introduction

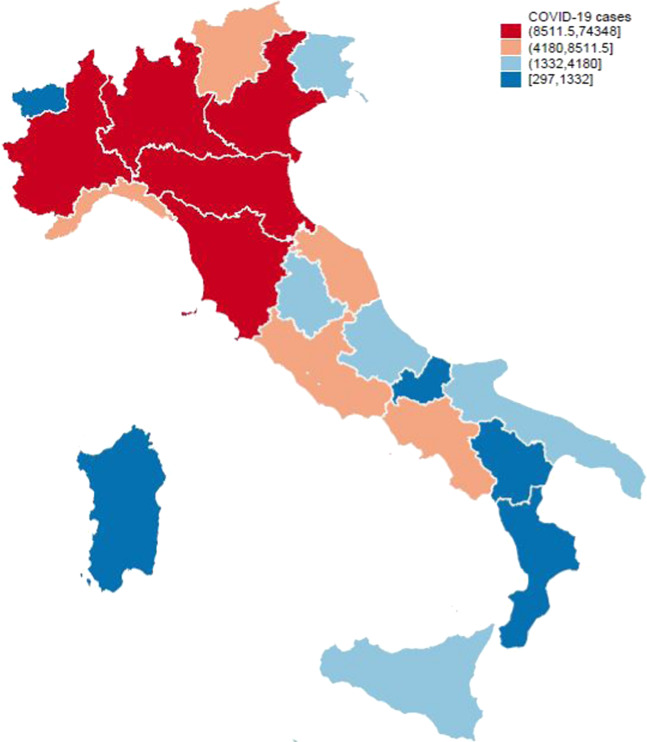

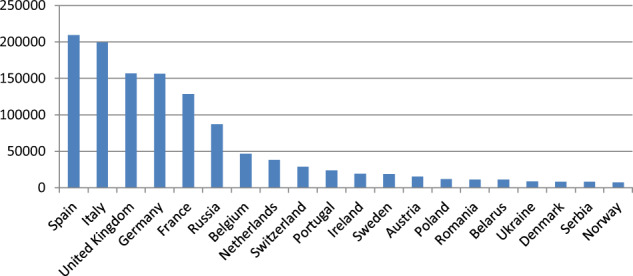

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the lives of hundreds of thousands of people around the world. Italy has experienced the worst outbreak in Europe, especially in the north. Italy was the first European country to report people infected with the novel Coronavirus and one of the countries with the highest number of cases (Figs. 1 and 2). At the beginning of March 2020, the Italian government imposed drastic measures to contain the growing epidemic: a lockdown on activities and public services, regulations prohibiting all movement by individuals unless for justified for work, health or other urgent necessities, school closures (as of February 25th), and required social distancing of at least one metre between individuals.1 While these measures have largely stemmed the spread of the virus, they have also had a huge impact on male and female labour market participation (see Barbieri et al. 2020; Casarico and Lattanzio 2020; Centra et al. 2020) and on inequality (Galasso 2020). We expect them to have substantially affected housework and childcare, too.

Fig. 1.

Number of COVID-19 cases by Italian region, as of 28 April 2020. Data retrieved from the Italian Ministry of Health

Fig. 2.

Number of COVID-19 cases by country, as of 28 April 2020. The graph includes the 20 most-affected European countries. Data retrieved from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

Evidence from past economic crises suggests that recessions often affect men’s and women’s employment differently, with a greater negative effect on men (Rubery and Rafferty 2013; Hoynes et al. 2012). As a consequence of the 2008 financial crisis, for instance, job losses were much greater in male-dominated sectors of the economy (notably construction and manufacturing), while women’s working hours actually increased. As reported in very recent studies (Hupkau and Petrongolo 2020; Alon et al. 2020), the current recession is instead likely to have a similar impact on male and female employment, since the social measures taken have affected sectors where both genders are employed (ILO 2020). A comparative study reports changes in the patterns of family life, manifesting in new work patterns and chore allocations in several European countries (Biroli et al. 2020). Using representative surveys from the USA and UK, other authors document how the pandemic affected the variation in the percentage of tasks that workers can do from home (Adams-Prassl et al. 2020).

In fact, the current COVID-19 crisis is not just an economic crisis, but a health and social one, too. The labour market is just one dimension of human work. COVID-19 is also expected to have major consequences on family work, due to increased housework and childcare resulting from the closing of schools and nurseries. Many women are already struggling to make it to work at all, given the need for at least one parent to stay home and mind the children (Queisser et al. 2020). Preliminary evidence from Spain (Farré et al. 2020) and from the UK (Sevilla and Smith 2020) shows that there has been a shift towards a more equal distribution of household and childcare between men and women, but most of the extra work caused by the crisis has fallen on women.

In this paper, we focus on Italy and investigate the effect of COVID-19 on work, housework and childcare arrangements of women and their male partners, both working before COVID-19. The Italian context is particularly interesting, not only because of the strict lockdown measures taken to contain the crisis, but also from a gender standpoint. Italy is characterized by both traditionally high gender gaps in the labour market and conservative gender roles, which put most of the burden of housework and childcare on women.2 Before the pandemic, a large proportion of grandparents (about 40% according to SHARE data) provided daily childcare. The mandatory implementation of social distancing has substantially reduced the availability of grandparental care, thus increasing the burden on families already caused by school and child-care facility closures. Higher fatality rates among the elderly may also have affected a large number of families living together or close by.3 In this context, we argue that the impact of COVID-19 on family work is related to the time that couples have to spend at home due to the emergency restrictions. Our goal is to understand how and to what extent family roles have changed since COVID-19 forced domestic partners to reorganize their time at home due to the lockdown. Is the increased time spent at home leading to a reallocation of couples’ roles in household chores and family care?

To answer this question, we use data on two representative samples of Italian women, working and non-working before the emergency. The data were collected in April 2020.4 We hypothesize different impacts on the division of labour between housework and childcare within the household depending on the working arrangements of women and their partners at the time of the outbreak of COVID-19.

Our empirical analysis shows that the new working arrangements have the potential to further increase women’s housework and childcare. Since we consider women and their partners, our data allow us to consider the allocation of housework and childcare within the couple. Our results indicate that men and women have reacted differently to the changing circumstances: 68% of women are spending more time in housework and 61% in childcare; the respective percentages for men are lower and equal to 40 and 51%. This result is consistent with findings from other real time data sets collected in Italy (Mangiavacchi et al. 2020) and other countries, such as the UK (Sevilla and Smith 2020) and Spain (Farré et al. 2020) which reported a greater contribution of men to childcare.

Our results raise concerns about the effect of COVID-19 on women’s labour market participation. Current work arrangements may make it even harder for women to participate than for men. More importantly, higher rates of male participation in domestic responsibilities, and particularly in housework, are associated to higher rates of female participation in the labour market (Fanelli and Profeta 2019). Thus, the consequences of COVID-19 on female labour market outcomes risk being amplified by the unequal intrahousehold allocation of extra work (housework and childcare) created by the emergency.

The paper is organized as follows: the next section describes the data and report some relevant statistics, Section 3 presents our main analysis and results, Section 4 discusses relevant policy implications and Section 5 concludes.

Data and descriptive statistics

In order to analyse the impact of COVID-19 measures on households and women, we use a representative sample of 800 Italian working women interviewed in April and July 2019 with the purpose of understanding inequalities in women’s work, savings and pensions. In April 2020, we repeated the interviews, adding specific questions related to the emergency.5 For comparison reasons, we also interview a similar sample of Italian non-working women.

We designed the questionnaire to gather information on changes in the respondents’ employment status, hours of work, childcare, income and satisfaction regarding their work and family during the emergency. We also included a set of ad-hoc questions regarding the time spent on housework and childcare before and after the COVID-19 outbreak. Women were also asked similar questions about their partners. Since we do not ask questions directly to partners, we acknowledge that there could be a bias in their reported hours.

Thanks to the level of detail of the questions asked, we were able to identify whether the women and their partners were allowed to continue working at their jobs after the lockdown. Since the interviews were conducted in late April 2020, we are able to observe the effects during the first phase of the emergency. Data from Italy’s so-called Phase 2, which started on May 4th, do not confound our estimates. We are poised to capture further changes and possible adjustments in women’s labour supply and behaviour during the next wave of the survey, provisionally forecast for January 2021.

Our survey was designed to gather data on four main areas that may have been affected by the health emergency: work, housework, childcare and home schooling. Changes in terms of work will be dependent on the respondent’s field of occupation, but changes in housework are likely to depend on the partner’s field, too.

Table 1 describes the sample used in our empirical analysis: coupled women with both partners working before the emergency (520 observations). The average age in our sample is 44 and 54% of the female workforce live in the northern regions, a percentage consistent with data from the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Also, almost half (47%) of respondents have a university degree. As ISTAT reports that the share of working women age 25–64 with a degree in 2018 was around one-third, we acknowledge that our sample is biased toward more educated women, who can access an online survey.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics on working women

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 43.88 | 9.21 | 26 | 64 | 520 |

| Having a degree | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 520 |

| North | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 520 |

| Centre | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 | 520 |

| Having children | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | 520 |

| Number of children | 1.66 | 0.74 | 1 | 7 | 350 |

| Number of children age 0–5 | 0.36 | 0.59 | 0 | 3 | 350 |

| Number of children age 6–10 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0 | 2 | 350 |

| Number of children age 11–14 | 0.25 | 0.47 | 0 | 2 | 350 |

| Number of children age ≥15 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 0 | 5 | 350 |

The sample is made up of coupled women where both partners were working before the emergency

More than two-thirds (67%) of working women in our sample have children. If we focus on the sub-sample of women living with a partner and at least one child (350 observations), we see that the average number of children is 1.66. We also have information on the age range of the offspring, which is important for determining the time spent on childcare and home schooling. We acknowledge that our sample is relatively small, yet very informative.

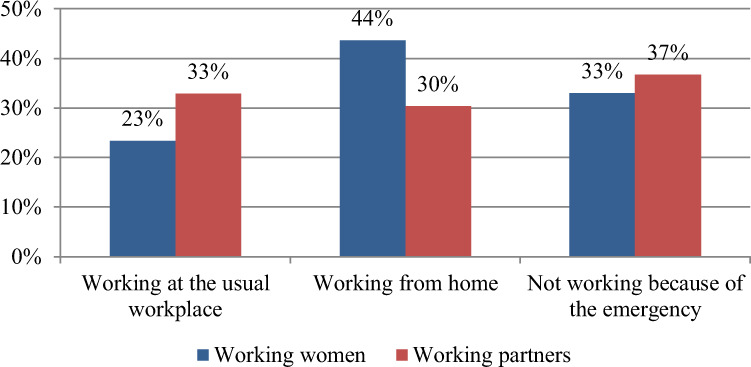

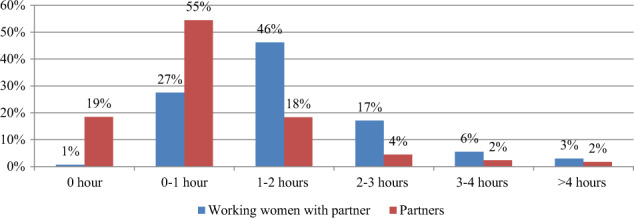

Additional descriptive statistics give us some preliminary insights. During COVID-19, women are less likely to have kept working in their usual workplace than men: just 23% of women as opposed to 33% of their partners. Instead, 44% of working women have kept their jobs by working from home (vs. 30% of men). Women are therefore much more likely to work from home. This raises the likelihood of increasing the overall workload of women, resulting from both their occupation and domestic work. About the same number of women and men have stopped working because of the emergency (33 and 37%) (see Fig. 3).6 Before the COVID-19 emergency, women spent significantly more time on housework than their partners (see Fig. 4): almost three quarters (74%) of men devoted <1 h a day to housework (as opposed to 28% of women).7

Fig. 3.

Percentage of working women and their partner by working arrangement during the COVID-19 emergency

Fig. 4.

Percentage of working women and their partners by hours of housework per day before the COVID-19 emergency

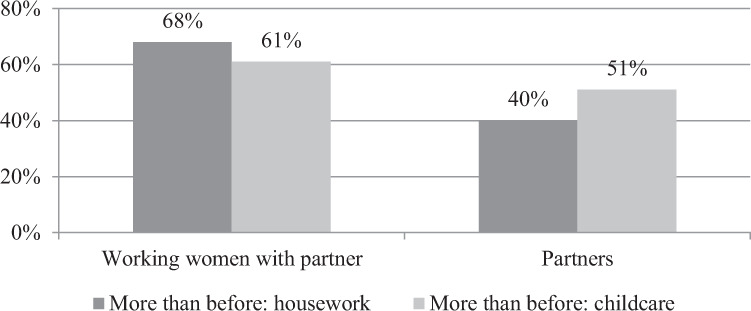

The COVID-19 measures adopted to contain the epidemic have massively increased the amount of housework and childcare that must be done. How is this extra burden distributed within the couple? While both men and women are spending more time on housework and childcare, the distribution is unequal: with 68% of women spending more time in housework and only 40% of men (see Fig. 5). The percentages for childcare are 61% and 51%, respectively. Hence, while most of the burden has fallen on women, the additional childcare is more equally shared than housework. The fact that between 40 and 51% of men are spending more time on housework and childcare is however noteworthy, and the COVID-19 emergency could represent an opportunity for men to be more engaged in unpaid work at home, also after the pandemic.

Fig. 5.

Percentage of working women and their partners doing more housework and spending more hours in childcare during the COVID-19 emergency

While these numbers provide an initial assessment of how COVID-19 affected the workload of working women and their working partners, they also make clear that, in order to assess whether and how COVID-19 changed the intra-family equilibrium of work and family work, we need to investigate the changes in work arrangements and in housework and childcare of women and their partners. We therefore set out to analyse how the division of labour within the household relates to the working arrangements of each of the partners after the lockdown. We show the percentages of men and women doing more housework and more childcare according to these possible combinations in Table 2 (panel a and b, respectively).

Table 2.

Housework and childcare

| Partners working at the usual workplace | Partners working from home | Partners not working because of the emergency |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Percentage of men and women doing more housework during the COVID-19 emergency by working arrangement | ||

| Women working at the usual workplace | ||

| Women 49% | Women 40% | Women 61% |

| Partners 28% | Partners 55% | Partners 58% |

| N = 57 | N = 20 | N = 33 |

| Women working from home | ||

| Women 78% | Women 65% | Women 64% |

| Partners 28% | Partners 40% | Partners 58% |

| N = 65 | N = 111 | N = 55 |

| Women not working because of the emergency | ||

| Women 82% | Women 81% | Women 74% |

| Partners 22% | Partners 24% | Partners 47% |

| N = 49 | N = 27 | N = 103 |

| The sample is made up of coupled women where both partners were working before the emergency (N = 520) | ||

| (b) Percentage of men and women spending more hours on childcare during the COVID-19 emergency by working arrangement | ||

| Women working at the usual workplace | ||

| Women 45% | Women 45% | Women 31% |

| Partners 40% | Partners 36% | Partners 54% |

| N = 40 | N = 11 | N = 26 |

| Women working from home | ||

| Women 54% | Women 77% | Women 60% |

| Partners 37% | Partners 60% | Partners 60% |

| N = 41 | N = 73 | N = 35 |

| Women not working because of the emergency | ||

| Women 70% | Women 68% | Women 71% |

| Partners 38% | Partners 63% | Partners 59% |

| N = 37 | N = 19 | N = 68 |

| The sample is made up of coupled women where both partners were working before the emergency (N = 350) | ||

Table 2 shows that both men and women are spending more time on domestic work. This is in line with results from Angelici and Profeta (2020), who report that in normal times, “smart working”8 (allowing flexibility in the working hours and location for certain number of hours each week) leads to increased participation of males in domestic work. Interestingly, this increase is seen more in childcare than housework in almost all cases. However, the distribution of the extra work within the couple appears to be highly unbalanced. The extra work is a burden mainly borne by women.

There are some exceptions. Increased participation by men overtakes that of women only when women continue to go to their usual place of work and their partner does not work because of the emergency. However, even under these circumstances, this is true only for childcare (where 54% of partners spend more time on childcare vs. only 31% of women), and not for housework (58% of partners spend more time on housework and 61% of women). When the woman telecommutes and the partner does not work, 60% of both men and women spend more time on childcare. Yet this balance disappears when we consider the amount of time spent on housework: 64% of women and 58% of men increase the amount of housework they do. Another case in which the increased participation of men in housework overtakes that of women is when women continue at their regular place of work and their partners telecommute. In symmetric situations, the distribution of extra work still penalizes women. For example, when both partners work at home, 65% of women increase their housework versus 40% of men. The corresponding percentages for childcare are 77% for women and 60% for men. Finally, when looking at the interrelation of increases in housework within the couple, we notice that in 37% of the households only the woman increases her time, while the opposite is true in just 7% of the cases. In 32% of the couples, both partners increase their time devoted to housework.

The empirical analysis

In this section, we estimate the determinants of changes in housework, childcare and home schooling during the COVID-19 emergency.

In order to answer our research question about the possible changes to the share of time spent on housework and childcare by the two partners, we estimate a set of multivariate regressions where we use as the dependent variable a dummy taking the value of one if the spouse/partner has spent more time, compared to the pre-COVID situation, on the following activities: household chores, time devoted to childcare, time devoted to home schooling. We estimate the regressions using linear probability models, and the results are confirmed by probit marginal effects.

In Tables 3 and 4, we show for both working women and their partner the determinants of more time devoted to housework, childcare, and home schooling respectively, conditioning on individual and family characteristics. Our sample consists of all coupled women, where both partners were working before the emergency.9 In both tables, the first column shows the regression results referring to women, while the second column refers to their partners.

Table 3.

Multivariate regression model of doing more housework during the COVID-19 emergency

| (1) Women doing more housework |

(2) Partners doing more housework |

|

|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age | 0.001 (0.002) | −0.007*** (0.002) |

| Woman having a degree | 0.014 (0.042) | 0.045 (0.044) |

| Woman having children | 0.059 (0.044) | 0.043 (0.045) |

| Woman working at the usual workplace | −0.283*** (0.057) | 0.130** (0.059) |

| Woman working from home | −0.073 (0.049) | 0.104** (0.051) |

| Partner working at the usual workplace | 0.062 (0.050) | −0.284*** (0.052) |

| Partner working from home | −0.004 (0.054) | −0.175*** (0.056) |

| North | 0.042 (0.048) | 0.041 (0.050) |

| Centre | 0.112* (0.060) | −0.007 (0.062) |

| Constant | 0.612*** (0.114) | 0.688*** (0.119) |

| Observations | 520 | 520 |

| R-squared | 0.056 | 0.078 |

Coefficient estimates from OLS regressions. The sample is made up of coupled women where both partners were working before the emergency. The baseline category for working arrangements is “Not working because of the emergency.” Standard errors in parentheses

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1

Table 4.

Multivariate regression model of spending more hours in childcare and doing more home schooling during the COVID-19 emergency

| (1) Women spending more hours in childcare |

(2) Partners spending more hours in childcare |

(3) Women doing more home schooling |

(4) Partners doing more home schooling |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age | −0.003 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.004 (0.004) | 0.002 (0.004) |

| Woman having a degree | 0.113** (0.052) | 0.158*** (0.053) | 0.090* (0.053) | 0.136** (0.053) |

| Number of children age 0–5 | 0.081 (0.057) | 0.161*** (0.058) | 0.092 (0.058) | 0.068 (0.058) |

| Number of children age 6–10 | 0.168*** (0.054) | 0.090 (0.055) | 0.296*** (0.055) | 0.161*** (0.055) |

| Number of children age 11–14 | 0.092 (0.058) | 0.050 (0.060) | 0.122** (0.060) | 0.034 (0.059) |

| Number of children age ≥15 | 0.016 (0.038) | −0.105*** (0.039) | −0.031 (0.039) | −0.071* (0.039) |

| Woman working at the usual workplace | −0.270*** (0.069) | 0.018 (0.070) | −0.123* (0.070) | 0.047 (0.070) |

| Woman working from home | −0.066 (0.061) | 0.018 (0.063) | −0.098 (0.063) | 0.024 (0.062) |

| Partner working at the usual workplace | −0.000 (0.060) | −0.215*** (0.061) | −0.011 (0.061) | −0.191*** (0.061) |

| Partner working from home | 0.065 (0.067) | −0.075 (0.069) | 0.062 (0.069) | −0.106 (0.069) |

| North | 0.003 (0.058) | −0.015 (0.059) | −0.038 (0.059) | 0.024 (0.059) |

| Centre | 0.082 (0.073) | −0.026 (0.074) | −0.021 (0.074) | 0.022 (0.074) |

| Constant | 0.638*** (0.186) | 0.275 (0.191) | 0.206 (0.191) | 0.250 (0.190) |

| Observations | 350 | 350 | 350 | 350 |

| R-squared | 0.147 | 0.160 | 0.160 | 0.122 |

Coefficient estimates from OLS regressions. The sample is made up of coupled women where both partners were working before the emergency. The baseline category for working arrangements is “Not working because of the emergency. Home schooling is included in childcare. Standard errors in parentheses

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1

In Table 3, we investigate the factors leading to more housework for working women and their working partners. The results consistently show a constant imbalance in the amount of time spent by men and women. Women spend more time on domestic work no matter where their workplace is, with one exception. The only case in which women are less likely to do more housework during the emergency is when they continue to work at their usual workplace. However, there is no difference in the increased amount of housework between women who keep working from home and those who are not working because of the emergency. Thus, women working remotely have to bear the workload of both their job and domestic responsibilities.

Conversely, when looking at their partners in the second column of Table 3, we notice that both men working at their usual workplace and those working from home are less likely to increase the number of hours spent on household chores than men not working because of the emergency. Moreover, while women’s housework is not affected by their partners’ working arrangement during the emergency, the opposite holds for men. In fact, men are more likely to spend additional time on chores when their partners are working. Finally, we notice that the partners of older women are less likely to increase the amount of housework they do.

Interestingly, this asymmetry is apparent only when housework is considered. Turning to childcare, the results on the additional time devoted to children are symmetric when either the woman or her partner works outside the home, as shown in Table 4, columns 1 and 2. It is worth noting that home schooling is included in the time devoted to childcare, Indeed, the only case in which both women and men are less likely to spend more time on childcare is when they work at their usual workplace. The partner’s working arrangement affects neither the mother’s nor the father’s childcare. One predictor of the time spent on taking care of the children is educational attainment: couples in which the mother holds a university degree are more likely to devote time to their children, even after controlling for other factors such as their working arrangements. Another predictor of higher child-related workload is the age of the children: children younger than 10 years old require more time from both working mothers and fathers.

The shutting down of schools, at any level, is likely to increase the amount of household work for parents. Many parents are squeezing in jobs or work-related tasks while also having to take on the responsibility for home schooling their children. Recent empirical evidence has shown that school closures and cancellations of exams are likely to have detrimental effects on children’s education as well as being a burden on their parents (Moroni et al. 2020). According to Sevilla and Smith (2020), the difference between the share of childcare done by women and the share done by men for the additional post-COVID19 hours of childcare is smaller than that for the allocation of pre-COVID19, and the allocation has become more equal in households where men telecommute or where they have lost their jobs.

We look more closely at the question of childcare by analysing the time devoted to children’s home schooling. In Table 4 columns 3 and 4, we again see that mothers holding a university degree and their partners spend more time on their children’s education. Hence, education translates into additional effort devoted to the care of children, including the amount of time spent on their children’s homework. This has the potential to sharpen educational differences among children due to family background. It is worth noting that individuals with higher educations are more likely to devote more time to their children (childcare and home schooling) while they do not significantly change their time devoted to household chores.

The age of children matters in determining the amount of effort devoted to them: one additional child in primary school age more than doubles the probability of devoting more time to home schooling than children in lower secondary school. The number of children below primary school age, instead, does not affect the probability of spending more time on home schooling. This evidence also holds for older children in upper secondary school.

Unsurprisingly, primary school aged children are more demanding: both partners spend more time helping primary school children with their homework. However, the increase in time devoted to children is always greater for women than for men. Again, our estimates show that the probability of spending more time on childcare is higher for women. Women spend more time on their primary-school age children, while their partners do not. For children over 15, the probability of devoting extra time is actually lower for male partners. For home schooling too, parents who continue to work at their usual workplace despite the emergency are less likely to spend more time with their children, while partners’ working arrangements have no influence on the number of hours an individual spends with her/his children.

In the appendix, we present a comparable analysis on our representative sample of households where women were not working before the emergency, and similar results for partners emerge (Table 6). When looking at housework in the second column of Table 6, the estimates confirm that both men working at their usual workplace and those working from home are less likely to increase the number of hours spent on household chores with respect to men not working because of the emergency. Similarly, partners are less likely to spend more hours in childcare when they work at the usual place, while this relation does not hold when looking at home schooling. Our estimates on non-working women also confirm that the age of children matters in determining the amount of time devoted to them: one additional child aged 6–10 raises the probability of devoting more time to home schooling, with a twofold increase for non-working mothers with respect to working fathers.

Table 6.

Multivariate regression model of doing more housework, spending more hours in childcare and spending more hours in home schooling during the COVID-19 emergency, for women who were not working before the emergency

| (1) Women doing more housework |

(2) Partners doing more housework |

(3) Women spending more hours in childcare |

(4) Partners spending more hours in childcare |

(5) Women doing more home schooling |

(6) Partners doing more home schooling |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age | −0.001 (0.003) | −0.004 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.005) | −0.009** (0.005) | −0.008* (0.004) | −0.005 (0.004) |

| Woman having a degree | −0.009 (0.072) | −0.008 (0.066) | 0.110 (0.079) | 0.078 (0.076) | 0.042 (0.071) | −0.075 (0.065) |

| Having children | 0.148** (0.062) | 0.008 (0.057) | ||||

| Number of children age 0–5 | −0.010 (0.074) | −0.041 (0.072) | 0.097 (0.067) | 0.010 (0.062) | ||

| Number of children age 6–10 | 0.287*** (0.062) | 0.191*** (0.060) | 0.388*** (0.056) | 0.167*** (0.051) | ||

| Number of children age 11–14 | 0.096 (0.066) | −0.038 (0.064) | 0.129** (0.060) | 0.014 (0.055) | ||

| Number of children age ≥15 | 0.001 (0.046) | −0.018 (0.044) | 0.017 (0.041) | −0.000 (0.038) | ||

| Partner working at the usual workplace | −0.095 (0.058) | −0.263*** (0.053) | −0.014 (0.063) | −0.219*** (0.061) | 0.020 (0.057) | −0.020 (0.052) |

| Partner working from home | −0.116* (0.068) | −0.144** (0.062) | −0.040 (0.075) | −0.073 (0.073) | −0.068 (0.067) | 0.070 (0.062) |

| North | −0.068 (0.057) | 0.082 (0.053) | −0.062 (0.061) | 0.089 (0.060) | −0.038 (0.055) | 0.020 (0.051) |

| Centre | −0.018 (0.072) | 0.078 (0.066) | 0.066 (0.079) | −0.013 (0.077) | −0.012 (0.071) | −0.097 (0.065) |

| Constant | 0.525*** (0.147) | 0.577*** (0.135) | 0.449* (0.240) | 0.858*** (0.233) | 0.614*** (0.216) | 0.395** (0.198) |

| Observations | 381 | 381 | 298 | 298 | 298 | 298 |

| R-squared | 0.031 | 0.075 | 0.132 | 0.152 | 0.285 | 0.101 |

Coefficient estimates from OLS regressions. The sample is made up of coupled women where partners were working before the emergency. Mean values of the dependent variables from column (1) to (6) are 0.52, 0.32, 0.51, 0.41, 0.43, and 0.21, respectively. Standard errors in parentheses

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1

Finally, we investigate the factors that are making working women’s work-life balance more difficult to achieve during the emergency. In particular, we use as dependent variables two dummies indicating whether the respondent reported that work-life balance was more difficult for her. Specifically, the first dummy variable takes the value of one if the respondent’s answer is “to some extent” or “very much” to the question “To what extent does an excessive amount of work make it more difficult to balance work and family?” The second dummy variable takes the value of one if the respondent’s answer is “to some extent” or “very much” to the complementary question “To what extent does an excessive amount of housework make it more difficult to balance work and family?”10 In the first column of Table 5, we can observe that those still working are those most likely to report it is difficult to balance work and family due to an excessive workload from their job. Interestingly, the second column of Table 5 shows that working women with children age 0–5 are those most likely to report it is difficult to balance work and family due to excessive domestic responsibilities. The work–life balance is especially difficult to achieve when the partner continues working outside of the home during the emergency. Also, older working women find the domestic work harder than their younger counterparts, even after controlling for the age of the children.

Table 5.

Multivariate regression model of reporting that “an excessive amount of work/housework made it more difficult to balance work and family” during the COVID-19 emergency

| (1) Work |

(2) Housework |

|

|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age | −0.002 (0.004) | 0.009** (0.004) |

| Woman having a degree | 0.069 (0.055) | 0.045 (0.056) |

| Number of children age 0–5 | 0.055 (0.059) | 0.176*** (0.060) |

| Number of children age 6–10 | 0.068 (0.057) | 0.088 (0.058) |

| Number of children age 11–14 | −0.029 (0.061) | 0.060 (0.062) |

| Number of children age ≥15 | −0.049 (0.040) | −0.079* (0.041) |

| Woman working at the usual workplace | 0.284*** (0.072) | 0.020 (0.073) |

| Woman working from home | 0.180*** (0.064) | 0.043 (0.065) |

| Partner working at the usual workplace | −0.109* (0.063) | 0.112* (0.064) |

| Partner working from home | −0.093 (0.071) | 0.104 (0.072) |

| North | −0.006 (0.060) | −0.011 (0.061) |

| Centre | 0.008 (0.076) | −0.016 (0.077) |

| Constant | 0.374* (0.195) | −0.100 (0.198) |

| Observations | 350 | 350 |

| R-squared | 0.082 | 0.087 |

Coefficient estimates from OLS regressions. The sample is made up of coupled women where both partners were working before the emergency. Standard errors in parentheses

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1

Policy implications

Are policy measures to contain COVID-19 gender neutral? Our results help understand important policy implications on the gender balance in the household.

The decision about work arrangements of different types of jobs has affected men and women differently, not only in terms of health exposure to the virus, but also because they have a significant impact on the amount of housework and childcare and its allocation within the couple. This in turn has potential substantial consequences on gender equality, as they challenge female participation to the labour force.

Our results also suggest that specific policy interventions introduced to face the emergency of COVID-19 may have important, perhaps neglected, indirect effects. The Italian government has introduced, among other measures, two policy interventions towards families and their work-life balance: an additional time period of parental leave (up to 30 days for parents of children aged <12 paid 30% of the salary) and a babysitter voucher. Starting from the extra parental leave, according to the data reported from the Italian National Social Security (INPS), on May 11, 2020, 76% of the requests come from women, of which 58% are in the age between 35 and 44, i.e., when women are likely to experience the highest pressure from work and family duties. The numbers are very similar across Italian regions. While we can argue that leaves are a necessary and desirable relief for many families facing the sudden shock of COVID-19 and the related containment measures, and we also notice that before Covid parental leaves were even more scarcely used by men (around 18% of men used it), this gender difference raises some concerns for the return to work of women.

The baby-sitter voucher, which will be extended to childcare centres as soon as they re-open, also represents a key policy for families with young children. Italian families resort little to care external to the family, because of its high cost and because of cultural stereotypes against the use of formal childcare for children aged 0–3. However, the literature (e.g., Del Boca et al. 2018) suggests that formal childcare has positive effects on children’s future learning and social skills and it is positively related to maternal employment. Hence, subsidizing childcare is expected to bring positive consequences on gender balance.

Critical determinants of both the prevalent use of leaves by women and the scarce use of formal childcare are the well-established gender stereotypes and cultural bias, which, as our analysis suggests, resist also the COVID-19 pandemic and the related changes of work arrangements. Thus, our results also suggest that these policies cannot be effective without a neutral and scientific information on their beneficial effects, for example on the benefit for children of attending formal childcare.

Additional gender effects may arise from policies related to the educational system, mainly schools. Our data show that the closure of schools critically increases childcare for parents in such a way which disproportionately affects women and which is likely unsustainable after the first months of the emergency.

Finally, working from home may also have important consequences on gender gaps. On one side, an appropriate flexibility is desirable for better work–life balance of both men and women. We have also highlighted the advantages of working from home, which may generate a better sharing of family work within the couple. On the other side, however, if this becomes a female-dominated option, with men mostly working at the workplace and women working from home, our results suggest a critical increase of unbalanced family work with most of the work borne by women.

Conclusions

While very recent studies have investigated the consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak on either female employment or housework or childcare separately, this is the first study that investigates them in the same context. Our results show that changes in these activities are interrelated and also depend on partners’ working arrangements during the emergency. Moreover, this is the first study which focuses on couples rather than on men and women separately, and thus appropriately addresses the allocation of duties within the family.

We show that the current crisis further increased the workload of women, resulting from both their occupation and the housework. In contrast with men, there is no difference in the increase of housework between women who telecommute and those who do not work because of the emergency. Compared to their partners, working women bear the brunt of the increased time needed for household chores and childcare. Men are more likely to be spending more time with the children, hence in more gratifying family work rather than chores. This result has important implications on female contributions to the economy, since greater male participation in housework would encourage women’s participation in the labour market.

We also shed light on a specific and crucial component of childcare: home schooling. The closure of schools has imposed a massive burden on parents, and especially on working parents. However, not all parents look after their children in the same way. While other studies have mentioned that men who telecommute are more likely to deal with childcare, and more educated people are more likely to telecommute, our unique data set allowed us to disentangle the effect of working from home from that of parents’ education on childcare. In particular, we show that mothers holding a degree and their partners spend much more time on their children’s education, even after controlling for their work arrangements. This has the potential to exacerbate educational differences among children due to their family background, as early education has a significant impact on child development. Thus, the long interruption due to the lockdown is likely to affect children’s outcomes later in life. We will analyse this outcome in future studies.

Finally, we identify the groups that are most vulnerable and most aware of the difficult work-family balance. We show that working women with young children, especially those aged 0–5, are those particularly affected, by bearing the excess burden to a higher extent. For women, the work–life balance is especially difficult to achieve when their partners keep working outside of the home during the emergency.

These results may have long-term implications, and implications that are potentially negative for women, especially if both the labour market crisis and school closures persist. However, there are also some positive implications, if it means that couples are taking the opportunity of the crisis to share the burden of childcare more equally.

Acknowledgements

This research was co-funded by the Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme of the European Union (Grant Agreement number: 820763) and coordinated by the “Dipartimento per le Pari Opportunità della Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri”. This project also received funding from the Collegio Carlo Alberto.

Appendix

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

For further details see: http://www.protezionecivile.gov.it/documents/20182/1227694/Summary+of+measures+taken+against+the+spread+of+C-19/c16459ad-4e52-4e90-90f3-c6a2b30c17eb

Comparative data show that when summing work in the labour market and work at home, Italian women not only work more than Italian men, but also more than men and women in most European countries (ISTAT 2019).

https://www.wsj.com/articles/family-is-italys-great-strength-coronavirus-made-it-deadly-11585058566.

The survey was administered by Episteme, a professional survey company. https://www.carloalberto.org/research/competitive-projects/clear-closing-the-gender-pension-gap-by-increasing-womens-awareness.

The survey was conducted with CAWI (computer-assisted web interviewing) interviews.

Four percent of women were fired or resigned compared to 2% of their partners.

The question on housework includes a couple of examples like cleaning and cooking. The question on childcare asks about the time devoted to children in general, including the time devoted to home schooling. In particular, the dummy is equal to one if the respondent answers “More than before” to the questions “Compared to the pre-emergency period, how did the time you/your partner devoted to chores/childcare/home schooling change?” The other possible answers were: “The same as before” and “Less than before”.

“Smart-working” is a new organization of work which includes flexibility of location (working from home, but also from another place different from the usual workplace) and flexibility of time (a personalized work schedule). Differently from teleworking, there is no strict control of the supervisor on time and place of work. During the COVID-19 emergency, some form of flexibility was used: many workers worked from home and, in some cases, with some flexibility of time. We do not have detailed information on the specific type of flexibility. Hence, we refer to this arrangement as “working from home”, or “telecommuting”.

We hence exclude households where the woman is not living with a partner and households where the partner is not working.

The other possible answers to both questions were: “Little” and “Not at all.”

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M., & Rauh, C. (2020). Work Tasks that can be done from home: evidence on variation within and across occupations and industries. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 1490.

- Alon, T. M., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. NBER Working Paper No. 26947.

- Angelici, M., & Profeta, P. (2020). Smart-working: work flexibility without constraints. Working Paper No. 137 Dondena Research Centre, Bocconi University.

- Barbieri, T., Basso, G., &. Scicchitano, S. (2020). Italian workers at risk during the Covid-19 epidemic. INAPP Working Paper No. 46.

- Biroli, P., Bosworth, S., Della Giusta, M., Di Girolamo, A., Jaworska, S., & Vollen, J. (2020). Family life in lockdown. IZA Discussion Paper No. 13398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Casarico, A., & Lattanzio, S. (2020). Nella “fase 2” a casa giovani e donne. Lavoce.info. https://www.lavoce.info/archives/66106/nella-fase-2-a-casa-giovani-e-donne/.

- Centra, M., Filippi, M., & Quaranta, R. (2020). Covid-19: misure di contenimento dell’epidemia e impatto sull’occupazione. INAPP Policy Brief No. 17.

- Del Boca, D., Monfardini, C., & See, S. G. (2018). Government education expenditures, pre-primary education and school performance: a cross-country analysis. IZA Discussion Paper No. 11375.

- Fanelli, E., & Profeta, P. (2019). Fathers’ involvement in the family, fertility and maternal employment: evidence from Central and Eastern Europe. Working Paper No. 131 Dondena Research Centre, Bocconi University. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Farré, L., Fawaz, Y., González, L., & Gaves, J. (2020). How the COVID-19 Lockdown Affected Gender Inequality in Paid and Unpaid Work in Spain. IZA Discussion Paper No. 13434.

- Galasso, V. (2020). Labour market inequalities. http://CEPRVoxEu.org.

- Hoynes H, Miller D, Schaller J. Who suffers during recessions? Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2012;26(3):27–48. doi: 10.1257/jep.26.3.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hupkau C., & Petrongolo, B. (2020) COVID-19 and the gender gaps: latest evidence and lessons from the UK. http://CEPRVoxEu.org.

- ILO (2020). ILO monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. Second edition. ILO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- ISTAT (2019). I tempi della vita quotidiana. Lavoro, conciliazione, parità di genere e benessere soggettivo. ISTAT, Rome, Italy.

- Mangiavacchi, L., Piccoli, L., & Pieroni, L. (2020). Fathers Matter: Intra-Household Responsibilities and Children’s Wellbeing during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. IZA Discussion Paper No. 13591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moroni, G., Nicoletti, C., & Tominey, E. (2020). Children’s socio-emotional skills and the home environment during the COVID-19 crisis. http://CEPRVoxEu.org.

- Queisser, M., Adema, W., & Clarke, C. (2020). COVID-19, employment and women in OECD countries. http://CEPRVoxEu.org.

- Rubery J, Rafferty A. Women and recession revisited. Work, Employment and Society. 2013;27(3):414–432. doi: 10.1177/0950017012460314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla, A., & Smith, S. (2020). Baby steps: the gender division of childcare after COVID19. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 14804.