Abstract

Objective

To quantify the number of medically unnecessary clinical visits and in-clinic contacts monthly caused by US abortion regulations.

Study Design

We estimated the number of clinical visits and clinical contacts (any worker a patient may come into physical contact with during their visit) under the current policy landscape, compared to the number of visits and contacts if the following regulations were repealed: (1) State mandatory in-person counseling visit laws that necessitate two visits for abortion, (2) State mandatory-ultrasound laws, (3) State mandates requiring the prescribing clinician be present during mifepristone administration, (4) Federal Food and Drug Administration Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy for mifepristone. If these laws were repealed, “no-test” telemedicine abortion would be possible for some patients. We modeled the number of visits averted if a minimum of 15 percent or a maximum of 70 percent of medication abortion patients had a “no-test” telemedicine abortion.

Results

We estimate that 12,742 in-person clinic visits (50,978 clinical contacts) would be averted each month if counseling visit laws alone were repealed, and 31,132 visits (142,910 clinical contacts) would be averted if all four policies were repealed and 70 percent of medication abortion patients received no-test telemedicine abortions. Over 2 million clinical contacts could be averted over the projected 18-month COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Medically unnecessary abortion regulations result in a large number of excess clinical visits and contacts.

Policy Implications

Repeal of medically unnecessary state and federal abortion restrictions in the United States would allow for evidence-based telemedicine abortion care, thereby lowering risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

1. Introduction

During the early months of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, health care providers across specialties reduced in-person contacts with patients to lower transmission risk while continuing to deliver essential care. The American Medical Association, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Society of Family Planning, and other leading clinical organizations have affirmed abortion constitutes essential health care during the pandemic [1], [2]. Providers can safely delivery abortion care to select patients via direct-to-patient telemedicine using mifepristone and misoprostol (medication abortion) [3], and ACOG has called for increased telemedicine abortion access during the pandemic [4]. Of the 862,320 abortions in the United States (US) annually, at least 66% are eligible for medication abortion by gestational age (≤10 weeks) [5]. Providing direct-to-patient telemedicine abortion could substantially reduce in-clinic contacts during the pandemic. However, state and federal policies currently impede the provision of telemedicine abortion.

There are currently four major policy barriers to telemedicine abortion in the US: (1) state laws that require a separate, in-person counseling visit followed by a mandatory waiting period prior to medical or surgical abortion (mandated counseling visit laws) (14 states); (2) state laws that require an ultrasound be performed at the time of abortion, even if an ultrasound has already been performed or gestational age is otherwise certain (11 states); (3) state laws that mandate the prescribing clinician be physically present during mifepristone administration (18 states); (4) the federal Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (FDA REMS) for mifepristone, which mandates the drug be given to the patient directly in the clinic or hospital setting under the supervision of the prescriber, precluding outpatient pharmacy dispensing and limiting mail delivery [6], [7], [8]. These regulations are medically unnecessary and do not enhance the safety of abortion [7], [9]. They also increase the number of clinic visits and in-clinic contacts required to access medical or surgical abortion, which in turn increases the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission among patients and healthcare workers.

We estimated the monthly number of excess clinical visits and resulting interpersonal clinical contacts (“in-clinic contacts”) caused by these policies in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

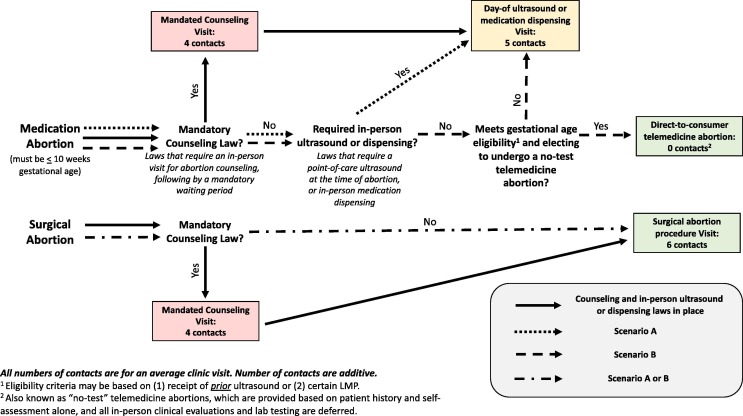

For a one-month period, we modeled the required number of clinical visits and in-clinic contacts for each state under current federal and state laws (baseline) to the visits that would be required under two hypothetical scenarios: (A) all mandated counseling visit laws are repealed (14 states); (B) all mandated counseling visit, day-of ultrasound, and dispensing laws and regulations (both state and federal) are repealed (all states). Scenario A assumed that all patients would continue to have one clinical visit for their abortion care; that is, all medically unnecessary mandated counseling visits would be averted, but medication and surgical abortion care would be delivered in-person, complying with Mifepristone dispensing regulations (FDA REMS and state-level policies) and ultrasound mandates. For the 36 states without mandated counseling visits, the number of averted visits (and in-clinic contacts) is zero under Scenario A. For scenario B, we assumed that the additional repeal of ultrasound and mifepristone dispensing laws would result in direct-to-consumer telemedicine abortions for clinically eligible patients with reliable gestational age dating. These “no-test” telemedicine abortions are provided based on patient history and self-assessment alone, and all in-person clinical evaluations and lab testing, including ultrasound and Rh typing, are deferred [3]. We modeled two different practices to determine gestational age: (1) prior ultrasound or (2) certain last menstrual period (LMP). These dating practices reflect variations in clinical practice, with some practitioners preferring ultrasound dating, while others use certain LMP [10]. For gestational dating practice 1, we assumed that 15% of abortion patients have had an ultrasound prior to presenting for abortion care. For gestational dating practice 2, we assumed 70% of patients have certain LMP dating [11]. Under Scenario B, only patients with reliable gestational age dating, by prior ultrasound or certain LMP, would be able to have direct-to-patient telemedicine abortion, and all other medication abortion patients would have one clinical visit for their abortion care. Fig. 1 details navigation through the care system under each scenario.

Fig. 1.

Patient navigation through medical abortion care under various state and federal regulations with the average number of contacts given for each encounter within the medical system. Refer to Table 1 for detail on types of in-clinic contacts for each visit.

For each state, we researched abortion incidence by abortion type (medication or surgical) from state-specific sources (e.g. vital statistics data) for the most recent year available (eTable 1 in Supplement). We assumed the one-month time period under analysis represents 1/12th of all abortions in a year. The national distribution for abortion type (39% medication abortion) was used when state-specific data were not available for 20 states [5]. For each visit type, we based the average number of clinical contacts on standard of care as described in the comprehensive clinical textbook on abortion in the US, conservatively assuming the fewest number of personnel that would be needed to meet standard of care under pandemic conditions [12]. Table 1 details the types of in-clinic contacts for each visit type. Specifically, during a mandatory counseling visit for either abortion type, we assumed that patients would come in contact with four persons at the clinic on average. For a day-of abortion ultrasound or medication dispensing visit for a medication abortion, we assumed an average of five contacts at the clinic. For a surgical abortion visit and same-day procedure, we assumed an average of six contacts at the clinic. No clinical visits or in-clinic contacts would occur for no-test telemedicine abortion patients.

Table 1.

Four visit types considered in modeling with corresponding average number of contacts, relevant scenario(s), and possible types of interpersonal contacts (listed in order of interaction).

| Visit type | Number of in-person visits | Average number of in-clinic contacts | Scenario(s) included in | Possible interpersonal contacts4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandated counseling (medication or surgical abortion) | 1 | 4 | Baseline1 | Security guard; Front desk staff; Counselor, MA, LPN, RN; Clinician (MD/DO/NP/CNM/PA) |

| Day-of ultrasound or medication dispensing (medication abortion) | 1 | 5 | Baseline1, A, or B2 | Security guard; Front desk staff; Counselor, MA, LPN, RN; Counselor, MA, LPN, RN; Clinician (MD/DO/NP/CNM/PA) |

| Telemedicine abortion (medication abortion) | 0 | 0 | B3 | None |

| Surgical abortion procedure (surgical abortion) | 1 | 6 | All | Security guard; Front desk staff; Counselor, MA, LPN, RN; Counselor, MA, LPN, RN; Counselor, MA, LPN, RN; Clinician (MD/DO/NP/CNM/PA) |

Baseline refers to the mandated visit types under a state’s current laws.

Patients not eligible for telemedicine abortions due to gestational age dating (based on either dating practice) will fall in this category under scenario B.

Patients eligible for telemedicine abortions due to gestational age dating (based on either dating practice) will only receive this visit type.

MA = medical assistant; LPN = licensed practical nurse; RN = registered nurse; MD = Medical doctor; DO = doctor of osteopathic medicine; NP = nurse practitioner; CNM = certified nurse midwife; PA = physician assistant

We used probabilistic modeling to account for potential variation in the number of in-clinic contacts for each visit and thereby generate a range of reasonable estimates of visits and contacts averted for each state. A zero-truncated Poisson distribution generated the number of in-clinic contacts for each visit with mean contacts depending on abortion type and scenario as described above. For the binary variables indicating medication abortion, prior ultrasound, and certain LMP for each individual, we used Bernoulli draws with probability equal to the state and/or national-level estimates discussed previously, as applicable. We generated 1000 simulated datasets for each state under the state’s baseline scenario, scenario A, and scenario B for each gestational age dating practice (ultrasound or LMP). We chose to incorporate variability in contacts at the visit-level to reflect the real-world heterogeneity in the number of in-clinic contacts during a visit, which potentially varies between patients within a practice. We computed the median difference in number of clinical visits and contacts between each state’s baseline and the scenarios with corresponding 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles. Table 2 includes detail on the model parameters and assumptions used in this analysis. All analyses were performed in R V3.6.0.

Table 2.

Parameter values used to calculate averted contacts and visits under three scenarios with corresponding references.

| Parameter | Value | Additional Detail | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laws active (baseline scenario) | Varies by state | Table 3 | [6], [7] |

| Number of abortions per month | Varies by state | eTable 1 | See supplemental references |

| Percent medication abortions | Varies by state | eTable 1 | See supplemental references |

| Number of contacts for mandated counseling visit (average) | 4 | Table 1, Fig. 1 | [11] |

| Number of contacts for day-of ultrasound or medication dispensing (average) | 5 | Table 1, Fig. 1 | [11] |

| Number of contacts for no-test telemedicine abortion | 0 | Table 1, Fig. 1 | [11] |

| Number of contacts for surgical abortion procedure (average) | 6 | Table 1, Fig. 1 | [11] |

| Percent of persons with certain LMP | 70% | [10] | |

| Percent of persons with prior ultrasound | 15% | Assumption based on internal chart review |

3. Results

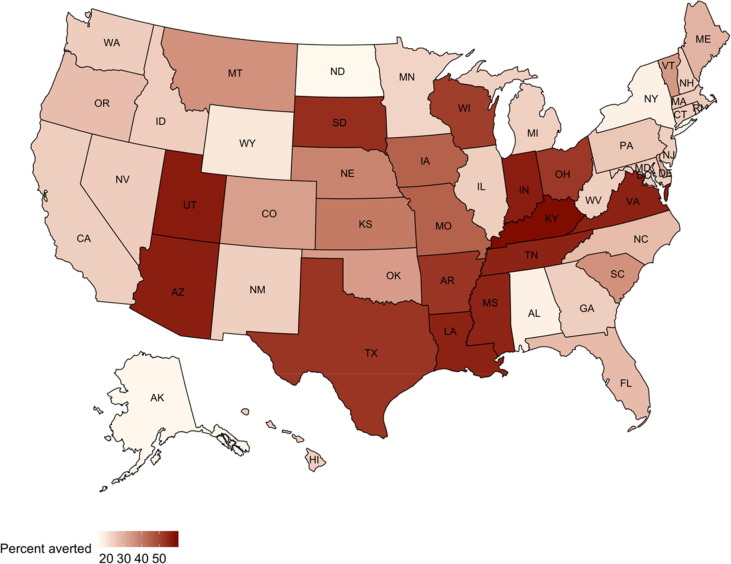

Nationally, we estimate that 12,742 in-person clinic visits (50,965 in-clinic contacts) would be averted each month if counseling visit laws alone were repealed. Further, 31,132 clinic visits (142,910 in-clinic contacts) would be averted if all day-of-abortion ultrasound laws and state and federal dispensing laws were repealed and patients with certain LMP (gestational dating practice 2) received no-test telemedicine abortions. Table 3 reports the estimated averted clinical visits under Scenario A and B (gestational dating practice 1 and 2) for each state; Table 4 reports the same information for the estimated averted in-clinic contacts. Under Scenario A, the state with the largest difference in averted visits was Texas with 4440 visits corresponding to 17,759 [17,501, 18,015] (2.5th and 97.5th percentiles from simulated datasets) fewer contacts than baseline. That is, if only the mandated counseling visit law were repealed in Texas, we could expect 4440 fewer unnecessary visits per month, almost 80,000 fewer visits over the projected course of the pandemic (18 months). Under Scenario B (gestational dating practice 2, certain LMP), the state with the largest averted visits was Texas with 5433 visits corresponding to 22,719 [22,343, 23,117] fewer in-clinic contacts monthly compared to baseline. Fig. 2 depicts the mean proportion change in in-clinic contacts for each state under Scenario B (gestational dating practice 2, certain LMP). The states with the largest proportion of averted in-clinic contacts were Kentucky (59.7%), Utah (57.1%), and Indiana (56.6%) (eTable 2 in Supplement).

Table 3.

Estimated clinical visits averted under various scenarios that repeal medically unnecessary abortion regulations and laws during a one-month time period.1

| State | Scenario A2: Clinical Visits Averted from Repeal of in-person Counseling Visit Laws Alone |

Scenario B, Ultrasound Dating Practice: Clinical Visits Averted by Repeal of in-person Counseling Visit plus mandated ultrasound and ma State and Federal Mifepris Dispensing Laws |

Scenario B, Certain LMP Dating Practice: Clinical Visits Averted by Repeal of in-person Counseling Visit plus mandated ultrasound and mandated State and Federal Dispensing Laws |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama*,^ | 0 | 22 [14,31] | 102 [85,121] |

| Alaska | 0 | 4 [1,9] | 21 [13,29] |

| Arizona+,*,^ | 1037 | 1099 [1085,1114] | 1328 [1299,1357] |

| Arkansas+,* | 256 | 268 [262,275] | 312 [301,326] |

| California | 0 | 647.5 [597,696] | 3018.5 [2928,3110] |

| Colorado | 0 | 58 [44,73] | 269 [245,296] |

| Connecticut | 0 | 58 [44,73] | 270 [244,297] |

| Delaware | 0 | 10 [5,17] | 48 [38,59] |

| District of Columbia | 0 | 27 [18,37] | 127 [110,145] |

| Florida^ | 0 | 387 [351,424] | 1805 [1731,1871] |

| Georgia | 0 | 176 [152,202] | 825 [778,874] |

| Hawaii | 0 | 15 [9,24] | 73 [60,86] |

| Idaho | 0 | 6 [2,11] | 29 [21,39] |

| Illinois | 0 | 207 [179,235] | 965 [909,1020] |

| Indiana+,*,^ | 670 | 710 [698,723] | 860 [839,883] |

| Iowa^ | 0 | 24 [16,34] | 112 [98,127] |

| Kansas^ | 0 | 54 [41,68] | 252 [229,274] |

| Kentucky+,* | 267 | 286 [278,295] | 357 [342,373] |

| Louisiana+,*,^ | 675 | 714 [704,727] | 860 [837,883] |

| Maine | 0 | 11 [5,18] | 52 [41,64] |

| Maryland | 0 | 145 [122,167] | 676 [632,722] |

| Massachusetts | 0 | 91 [73,108] | 423 [390,456] |

| Michigan | 0 | 123 [102,145] | 570 [531,613] |

| Minnesota | 0 | 46 [34,60] | 214 [190,238] |

| Mississippi+,*,^ | 212 | 224 [218,231] | 270 [257,282] |

| Missouri+,* | 242 | 246 [243,250] | 262 [254,270] |

| Montana | 0 | 11 [6,18] | 54 [43,65] |

| Nebraska* | 0 | 15 [9,23] | 71 [59,85] |

| Nevada | 0 | 47 [35,61] | 221 [197,245] |

| New Hampshire | 0 | 11 [5,17] | 49 [38,61] |

| New Jersey | 0 | 235 [207,263] | 1095 [1041,1152] |

| New Mexico | 0 | 22 [14,32] | 105 [88,122] |

| New York | 0 | 282 [250,314] | 1321 [1256,1384] |

| North Carolina* | 0 | 152 [128,175] | 707 [662,750] |

| North Dakota* | 0 | 4 [1,8] | 18 [11,26] |

| Ohio+ | 1702 | 1779 [1763,1796] | 2063 [2031,2097] |

| Oklahoma* | 0 | 33 [23,44] | 153 [135,171] |

| Oregon | 0 | 46 [34,59] | 215 [192,240] |

| Pennsylvania | 0 | 155 [133,178] | 726 [683,769] |

| Rhode Island | 0 | 17 [10,25] | 79 [65,93] |

| South Carolina* | 0 | 32 [22,43] | 150 [132,169] |

| South Dakota+,* | 32 | 33 [32,36] | 40 [35,45] |

| Tennessee+,* | 1012 | 1071 [1057,1087] | 1287 [1259,1314] |

| Texas+,*,^ | 4440 | 4654 [4627,4683] | 5433 [5380,5489] |

| Utah+ | 244 | 259 [252,268] | 316 [301,330] |

| Vermont | 0 | 8 [3,14] | 37 [28,46] |

| Virginia+,^ | 1434 | 1518 [1500,1535] | 1826 [1792,1858] |

| Washington | 0 | 87 [70,105] | 404 [372,435] |

| West Virginia* | 0 | 7 [2,12] | 32 [23,42] |

| Wisconsin+,*,^ | 519 | 540.5 [532,550] | 621 [602,638] |

| Wyoming | 0 | 0 [0,3] | 3 [0,6] |

| United States | 12742 | 16682 [16577,16794] | 31132 [30896,31356] |

Median and [2.5th, 97.5th] percentiles from 1000 simulated datasets.

No variation in scenario A as the number of visits is fixed and the same for both abortion types.

State has in-person separate counseling visit mandate.

State has physician dispensing law.

State has required ultrasound law.

Table 4.

Estimated in-clinic contacts averted under various scenarios that repeal medically unnecessary abortion regulations and laws during a one-month time period.1

| State | Scenario A: In-Clinic Contacts Averted from Repeal of in-person Counseling Visit Laws Alone |

Scenario B, Ultrasound Dating Practice: In-Clinic Contacts Averted by Repeal of in-person Counseling Visit plus mandated ultrasound and State and Federal Dispensing Laws |

Scenario B, Certain LMP Dating Practice: In-Clinic Contacts Averted by Repeal of in-person Counseling Visit plus mandated ultrasound and State and Federal Dispensing Laws |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama*,^ | 0 | 109 [67,159] | 513 [427,618] |

| Alaska | 0 | 20 [3,48] | 102 [62,151] |

| Arizona+,*,^ | 4145 [4034,4267] | 4456.5 [4323,4604] | 5601 [5404,5797] |

| Arkansas+,* | 1024 [964,1083] | 1086 [1014,1157] | 1305 [1220,1398] |

| California | 0 | 3240.5 [2967,3499] | 15084 [14590,15587] |

| Colorado | 0 | 288 [221,372] | 1348 [1203,1497] |

| Connecticut | 0 | 290 [214,375] | 1353 [1213,1497] |

| Delaware | 0 | 51 [22,89] | 242 [184,305] |

| District of Columbia | 0 | 135 [87,189] | 633 [535,741] |

| Florida^ | 0 | 1938 [1727,2135] | 9023.5 [8623,9421] |

| Georgia | 0 | 880 [740,1020] | 4125 [3853,4404] |

| Hawaii | 0 | 78 [42,122] | 364 [289,445] |

| Idaho | 0 | 30 [10,61] | 146.5 [100,202] |

| Illinois | 0 | 1034 [893,1183] | 4821 [4545,5134] |

| Indiana+,*,^ | 2682 [2581,2776] | 2886.5 [2760,2995] | 3636 [3479,3797] |

| Iowa^ | 0 | 121 [76,172] | 563 [483,657] |

| Kansas^ | 0 | 269 [196,349] | 1257.5 [1123,1400] |

| Kentucky+,* | 1067 [1006,1129] | 1161 [1094,1237] | 1520 [1415,1624] |

| Louisiana+,*,^ | 2701 [2603,2796] | 2901.5 [2786,3015] | 3623.5 [3462,3784] |

| Maine | 0 | 54 [24,93] | 260 [197,332] |

| Maryland | 0 | 725 [614,847] | 3388 [3134,3630] |

| Massachusetts | 0 | 454 [356,551] | 2114.5 [1935,2303] |

| Michigan | 0 | 615 [499,735] | 2850 [2633,3076] |

| Minnesota | 0 | 227.5 [164,300] | 1072.5 [936,1203] |

| Mississippi+,*,^ | 848 [795,902] | 909.5 [844,979] | 1135 [1043,1229] |

| Missouri+,* | 969 [913,1021] | 988 [932,1048] | 1068 [995,1142] |

| Montana | 0 | 56 [26,94] | 270 [207,340] |

| Nebraska* | 0 | 77 [41,123] | 354.5 [288,432] |

| Nevada | 0 | 236 [171,309] | 1105.5 [973,1248] |

| New Hampshire | 0 | 53 [24,91] | 247 [189,314] |

| New Jersey | 0 | 1172 [1022,1336] | 5474 [5170,5754] |

| New Mexico | 0 | 111 [66,166] | 521 [429,619] |

| New York | 0 | 1409 [1238,1600] | 6607 [6242,6941] |

| North Carolina* | 0 | 758.5 [629,887] | 3528 [3274,3786] |

| North Dakota* | 0 | 19 [3,42] | 90 [54,134] |

| Ohio+ | 6810.5 [6652,6968] | 7194 [7025,7382] | 8610 [8390,8855] |

| Oklahoma* | 0 | 164 [109,222] | 764 [660,877] |

| Oregon | 0 | 228 [165,305] | 1074 [944,1207] |

| Pennsylvania | 0 | 776 [651,915] | 3626 [3380,3876] |

| Rhode Island | 0 | 83 [45,130] | 395 [319,476] |

| South Carolina* | 0 | 160 [107,221] | 749 [647,864] |

| South Dakota+,* | 128 [108,151] | 136 [113,163] | 166 [135,201] |

| Tennessee+,* | 4046 [3927,4165] | 4340 [4204,4492] | 5418 [5227,5607] |

| Texas+,*,^ | 17,759 [17501,18015] | 18,828 [18523,19107] | 22,719 [22343,23117] |

| Utah+ | 976 [917,1037] | 1053 [983,1132] | 1335 [1238,1440] |

| Vermont | 0 | 39 [15,71] | 186 [135,238] |

| Virginia+,^ | 5736 [5599,5879] | 6157 [5985,6325] | 7700 [7465,7942] |

| Washington | 0 | 432 [339,531] | 2019 [1830,2202] |

| West Virginia* | 0 | 33 [11,63] | 161 [111,216] |

| Wisconsin+,*,^ | 2076 [1995,2162] | 2182.5 [2092,2275] | 2584 [2465,2710] |

| Wyoming | 0 | 0 [0,15] | 13 [0,33] |

| United States | 50,978 [50549,51388] | 70,668 [69893,71513] | 142,910 [141600,144226] |

Median and [2.5th, 97.5th] percentiles from 1000 simulated datasets.

State has in-person separate counseling visit mandate.

State has physician dispensing law.

State has required ultrasound law.

Fig. 2.

Percent difference in estimated in-clinic contacts under the state’s current medically unnecessary abortion restrictions (Baseline Scenario, Table 2) vs. under conditions in which medically unnecessary restrictions are repealed and all clinicians offer telemedicine abortion to all eligible patients with certain last menstrual period (Scenario B, Certain LMP Dating Practice, Table 4).

4. Discussion

Abortion restrictions may facilitate disease transmission during a pandemic by increasing the number of unnecessary visits and contacts required for care. These contacts are the result of public policy rather than clinician judgment or patient preference. Prior to the pandemic, people of color and low-income individuals experienced disproportionate barriers to and need for abortion care [13], [14]. In the wake of the pandemic, these policies and resultant unnecessary visits could further increase transmission risk for populations already highly impacted by COVID-19 illness, without clinical benefit [15].

This study has several limitations. We used pre-pandemic abortion incidence data to estimate the number of abortions occurring for a monthlong period during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is possible the pandemic has increased abortion demand, given its significant economic impact, or increased the need for second trimester abortion due to delays in care. Alternatively, it is possible that pregnancy rates and, thus, demand for abortion care, have decreased during the pandemic. A small proportion (5.4%) of abortions occur after 16 weeks gestation [5], and we did not account for the additional visit these procedures sometimes require for cervical ripening. If no-test telemedicine abortion were widely available, more patients may choose medication abortion over surgical abortion, further decreasing the visits and contacts required for abortion care. We also assumed a conservative (minimal) average number of interpersonal contacts – for instance, during a medication abortion visit, we assumed one interaction with security personnel, one with clerical personnel, two clinical personnel (such as medical assistants and counselors), and one with the dispensing clinician. In practice, patients may come into contact with additional personnel, such as dedicated ultrasound staff. It is unknown whether different types of contact during an in-person visit carry different risks of viral transmission. In addition, we did not consider non-clinical contacts that were a direct result of the visit, such as childcare or transit. Collectively, these limitations likely resulted in an underestimate of contacts caused by current policies.

Lastly, we did not account for heterogeneity in clinical practice and patient preference. We assumed that prior to the pandemic, very few medication abortions were being provided as no-test telemedicine abortion with no in-person dispensing visit, with the exception of current telemedicine research protocols [16]. In addition, we assumed every clinician either only accepted prior ultrasound (Scenario B, gestational dating practice 1) or always accepted certain LMP (Scenario B, gestational dating practice 2) to determine gestational age eligibility for no-test telemedicine abortion, and that all patients eligible for no-test medication abortion would choose this method over an in-person visit. We assumed that all patients who chose surgical abortion pre-pandemic would continue to do so, rather than choosing a no-test medication abortion if eligible. In reality, clinical practice and patient preference would fall between these two extremes.

Importantly, we only considered two hypothetical policy scenarios, and modeled state laws as they stood on January 1, 2020. In July 2020, two legal changes occurred that could potentially reduce the number of clinic visits and clinical contacts required to access abortion care moving forward: (1) Virginia’s repeal of their waiting period and mandatory ultrasound laws went into effect, and (2) a federal judge temporarily enjoined the in-person dispensing requirement of the REMS pending further litigation [17], [18]. These changes, and any future repeals of similar abortion restrictions, could reduce viral transmission risk related to accessing abortion care during the COVID-19 pandemic. To model the potential varied future legal and regulatory scenarios, we created a publicly available online tool which allows users to compute the number of averted visits and contacts under different practice-level and legislative circumstances. The tool is available at: https://harvard-data-science.shinyapps.io/averted_ab_visits/.

While access to no-test telemedicine abortion holds potential to expand abortion access and reduce unnecessary visits and contacts, in-clinic abortion must remain accessible during the COVID-19 pandemic to accommodate patients who are ineligible for medication abortion, need additional evaluation or testing before medication abortion (for instance, patients with unknown LMP), or are unable to complete telemedicine visits due to lack of internet, phone access, or privacy in their homes.

We estimate that medically unnecessary abortion regulations resulted in 31,132 additional clinic visits (142,910 in-clinic contacts) each month during the early COVID-19 pandemic. These restrictions have dangerous implications for patients and health workers during the pandemic, and each additional month these policies are in place, the number of unnecessary clinical contacts will increase. The resultant increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission disproportionately affects patients who are low-income, identify as Black and/or Hispanic/Latinx, and who live in regions without abortion providers, thus potentially further exacerbating profound racial inequities in COVID-19 disease [13], [14], [15]. Policy change – permanently removing the FDA dispensing requirement and repealing state laws that mandate medically unnecessary visits – is critical to allow clinicians to practice evidence-based abortion care and respond effectively to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests:The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2020.08.017.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Joint statement on abortion access during the COVID-19 outbreak, https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2020/03/joint-statement-on-abortion-access-during-the-covid-19-outbreak; 2020. [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- 2.American Medical Association. AMA statement on government interference in reproductive health care. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/ama-statements/ama-statement-government-interference-reproductive-health-care; 2020. [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- 3.Raymond E., Grossman D., Mark A. Medication abortion: A sample protocol for increasing access during a pandemic and beyond. Contraception. 2020;101:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. COVID-19 FAQs for Obstetrician–Gynecologists, Gynecology. https://www.acog.org/en/clinical-information/physician-faqs/COVID19-FAQs-for-Ob-Gyns-Gynecology; 2020. [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- 5.Jones RK, Witwer E, Jerman J. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2017. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-incidence-service-availability-us-2017; 2019. [Accessed 14 April 2020].

- 6.Guttmacher Institute. An overview of abortion laws, state laws and policies (as of April 2020). https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-abortion-laws; 2020. [Accessed April 14, 2020].

- 7.Raymond E.G., Chong E., Hyland P. Increasing access to abortion with telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):585–586. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaiser Family Foundation. State ultrasound requirements in abortion procedure (as of May 1, 2019). https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/state-indicator/ultrasound-requirements/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D; 2019. [Accessed April 14, 2020].

- 9.Grossman D., Grindlay K. Safety of medical abortion provided through telemedicine compared with in person. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4):778–782. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bracken H., Clark W., Lichtenberg E.S. Alternatives to routine ultrasound for eligibility assessment prior to early termination of pregnancy with mifepristone-misoprostol. BJOG. 2011;118(1):17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schonberg D., Wang L., Bennett A., Gold M., Jackson E. The accuracy of using last menstrual period to determine gestational age for first trimester medication abortion: A systematic review. Contraception. 2014;90(5):480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul M., Licthenberg E.S., Borgatta L., Grimes D.A., Stubblefield P.G., Creinin M.D., editors. Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy: comprehensive abortion care. Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dehlendorf C., Harris L.H., Weitz T.A. Disparities in abortion rates: a public health approach. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1772–1779. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bearak J.M., Burke K.L., Jones R.K. Disparities and change over time in distance women would need to travel to have an abortion in the USA: a spatial analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(11):e493–e500. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30158-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 – COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6915e3.htm; 2020. [Accessed 17 April 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Raymond E. TelAbortion: evaluation of a direct to patient telemedicine abortion service in the United States. Contraception. 2019;100(3):173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattingly, Jusin. Northam signs bills to roll back abortion restrictions. Richmonds Times-Dispatch. 10 April 2020. Accessed on 24 July 2020. Available at: https://richmond.com/news/virginia/northam-signs-bills-to-roll-back-abortion-restrictions/article_26cba5d2-6c10-59dd-9de8-b977df3dee9f.html.

- 18.United States District Court District of Maryland. Civil Action No. TDC-20-1320. 13 July 2020. Accessed on 24 July 2020. Available at: https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/093111166803.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.