Abstract

Purpose

Randomized controlled trials demonstrate that omission of radiation therapy (RT) in older women with early-stage cancer undergoing breast conserving surgery (BCS) is an “acceptable choice.” Despite this, high RT rates have been reported. The objective was to evaluate the impact of patient- and system-level factors on RT rates in a contemporary cohort.

Methods

Through the National Cancer Data Base, we identified women with clinical stage I estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer who underwent BCS (n = 84,214). Multivariable logistic regression identified patient, tumor, and system-level factors associated with RT. Joinpoint regression analysis calculated trends in RT use over time stratified by age and facility-type, reporting annual percent change (APC).

Results

RT rates decreased from 2004 (77.2%) to 2015 (64.3%). The decline occurred earliest and was most pronounced in older women treated at academic facilities. At academic facilities, the APC was − 5.6 (95% CI − 8.6, − 2.4) after 2009 for women aged > 85 years, − 6.4 (95% CI − 9.0, − 3.8) after 2010 for women aged 80 − < 85 years, − 3.7 (95% CI − 5.6, − 1.9) after 2009 for women aged 75 − < 80, and − 2.4 (95% CI, − 3.1, − 1.6) after 2009 for women aged 70 − < 75. In contrast, at community facilities rates of RT declined later (2011, 2012, and 2013 for age groups 70–74, 75–79, and 80–84 years).

Conclusions

RT rates for older women with early-stage breast cancer are declining with patient-level variation based on factors related to life expectancy and locoregional recurrence. Facility-level variation suggests opportunities to improve care delivery by focusing on barriers to de-implementation of routine use of RT.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Radiation, Breast conserving therapy, Elderly, Lumpectomy, De-escalation

Introduction

Published in 2004, data from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 9343 study addressed uncertainty regarding the use of adjuvant radiation therapy (RT) in older women with early-stage breast cancer [1]. This landmark randomized trial demonstrated that for women age 70 years or older with clinical stage I estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, the addition of RT to hormonal therapy following breast conserving surgery (BCS) led to a decreased rate of locoregional recurrence (LRR) at five years. However, there was no change in rates of mastectomy, distant metastases, or overall survival. These findings were reinforced with the publication of 10-year outcomes in 2013 [2]. As a result of these data, the authors concluded that avoidance of adjuvant RT in this subgroup of women was a “reasonable choice”.

Not long after initial publication of the CALGB 9343 results, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 2005 Clinical Practice Guidelines were revised to allow for the omission of RT following BCS in certain groups of older women [3]. The findings of CALGB 9343 were also reinforced through other large clinical trials [4, 5]. However, persistently high use of post-BCS RT in older women have been reported in prior observational studies, suggesting little impact of trial results and guideline changes on clinical practice patterns [6–10]. While other studies do report a decreasing overall trend in adjuvant RT in this patient population, the data suggest inconsistencies in utilization across regions and institutions [11–15].

We hypothesized that sustained use of adjuvant RT in older women reflects tailored implementation of the CALGB 9343 study results based on patients’ overall health and life expectancy as well as the perceived risk of LRR due to tumor characteristics, rather than a failure to de-escalate ineffective clinical care [16]. As such, the objective of this study was to compare the impact of clinical and tumor characteristics at the patient-level with system-level factors on the rate of adjuvant RT utilization following BCS in a contemporary cohort of women over the age of 70 years.

Methods

Data source and cohort selection

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) [17]. The NCDB is the result of a joint collaboration between the American Cancer Society and the American College of Surgeons and includes over 70% of newly diagnosed cancer patients in the USA and Puerto Rico. The NCDB is a registry-based database and data are abstracted from medical records at approximately 1400 institutions nation-wide using a standardized abstraction manual.

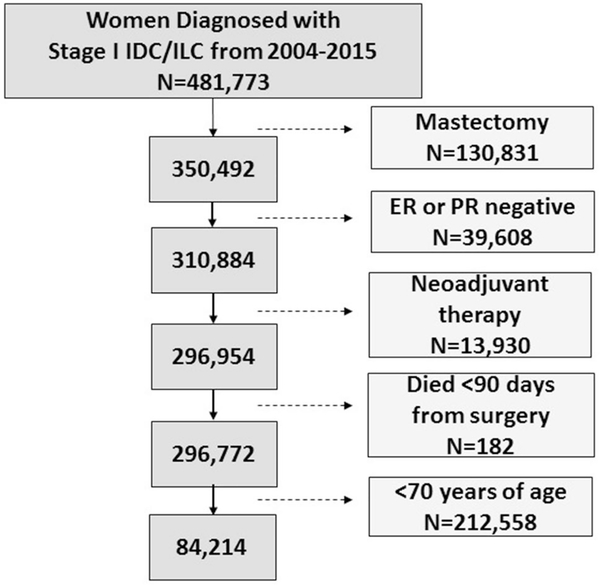

We selected our cohort based on entry criteria for the CALBG 9343 trial (Fig. 1) [1]. We selected patients who were treated between 2004 and 2015 as this time period corresponds to the timing of the publication of CALGB 9343. We identified women with clinical stage I (T1N0M0) estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer who underwent BCS. Additional exclusion criteria included receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or neoadjuvant radiation, and women who died within 90 days of diagnosis. A total of 84,214 women aged 70 years and older were included in the analyses. While our primary patients of interest were women aged 70 years and over, we also included women aged 65 to 69 years (n = 48,805) to control for overall time trends in the use of radiation nationally.

Fig. 1.

Exclusion and inclusion criteria

Outcome measures

Our primary outcome was the rate of first course adjuvant RT over time, defined using the “RX_SUMM_RADIATION” RT summary variable within the NCDB. We examined alternative definitions using variables such as radiation start or end dates as used in other studies [10]; however, as most patients with a missing value for radiation start date (95.3%) were recorded as having “no radiation” per the “RX_SUMM_RADIATION” variable, we felt most comfortable using the summary radiation variable provided by the NCDB. We described the proportion of women undergoing partial breast radiation, defined as 5–10 treatments over a 1–2 week period [10, 18] Patient demographics and disease characteristics including year of diagnosis, Charlson Comorbidity Index [19], insurance type, tumor grade and Her2neu status, treatment characteristics, and facility type were used as covariates. The facility type assigned to each patient reflects the facility that reported the patients’ cancer data and where most of their care was received; we cannot definitively say whether a patient’s surgery or radiation occurred at that facility.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patient demographics and Chi-squared tests were used to assess differences between age groups. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify patient (age, race, comorbidities, year of diagnosis), disease (grade, Her2neu status, margin status, chemotherapy, endocrine therapy), and system-level (facility type, geographic region) factors associated with receipt of adjuvant RT. Analyses were performed using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

We used Joinpoint regression analysis to calculate trends in receipt of adjuvant RT over time based on key factors identified through the multivariable logistic regression model [20–23]. Joinpoint regression analysis is a method of characterizing temporal trends by calculating changes in the rates of an outcome (i.e., receipt of adjuvant radiation) over time. This technique determines whether multiple regression lines provide a better fit for the data than a single straight line. The presence of multiple regression lines suggests that the rate of change (the slope of the line) is different before and after one or more discrete points in time. The Joinpoint software provides statistical estimation of when the change(s) in slope occurred, with a p value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. The slope of the line is calculated as the annual percent change (APC). The APC represents the change in rate on an annual basis; a horizontal line is equivalent to no change over time and thus an APC of zero, whereas a declining line would have a − APC value. The software also calculates the likelihood that this APC is significantly different from zero and, therefore, represents a true trend (p < 0.05). Based on the multivariable logistic regression models, we calculated the APC for the overall cohort stratified by age and type of treatment facility. We restricted each model to no more than one joinpoint over the study period.

Results

Cohort characteristics for the 84,214 women age 70 years and older that met eligibility criteria for CALGB 9343 are described in Table 1. The majority of eligible women (75%) initiated endocrine therapy. Of women aged 70 years and older, 61,091 (72.5%) received adjuvant RT during our study time period; this overall rate ranged considerably from 81.8% of women aged 70–75 years to 45.4% of women age 85 years and older. Univariate analysis demonstrated a significant difference in overall rate of adjuvant RT when stratified by patient age (p < 0.0001). Further, older women were more likely to receive partial breast irradiation (15% of women aged 70 − < 75 years, 16% aged 75 − < 80 years, 17% aged 80 − < 85 years, and 20% aged > = 85 years, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patient cohort and multivariable model of factors associated with adjuvant radiation

| % (N = 84,214) | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years of age) | < 0.001 | ||

| ≥ 70–75 | 44.9% (37,802) | Ref | |

| ≥ 75–80 | 31.4% (26,464) | 0.65 (0.63–0.67) | |

| ≥ 80–85 | 17.1% (14,436) | 0.38 (0.36–0.40) | |

| ≥ 85 | 6.6% (5,512) | 0.20 (0.19–0.21) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 80.4% (67,711) | Ref | |

| 1 | 16.1% (13,515) | 0.85 (0.81–0.88) | |

| 2 | 3.5% (2,988) | 0.66 (0.61–0.72) | |

| Grade | < 0.001 | ||

| Well differentiated | 37.0% (31,134) | Ref | |

| Moderately differentiated | 48.2% (40,546) | 1.2 (1.1–1.2) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 10.5% (8,847) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | |

| Unknown | 4.4% (3,787) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | |

| Her2neu | 0.5 | ||

| Negative | 60.7% (51,154) | Ref | |

| Positive | 3.0% (2,539) | 1.1 (0.97–1.2) | |

| Unknown | 36.2% (30,521) | 1.0 (0.95–1.1) | |

| Positive margin | 3.6% (3,042) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.01 |

| Insurance | 0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 88.5% (74,520) | Ref | |

| Medicare + private | 11.5% (9,694) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | |

| Facility type | < 0.001 | ||

| Academic | 25.4% (21,358) | Ref | |

| Comprehensive community | 52.4% (44,086) | 1.3 (1.3–1.4) | |

| Community | 11.7% (9,864) | 1.2 (1.2–1.3) | |

| Integrated | 10.6% (8,906) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | |

| Geographic region | < 0.001 | ||

| New England | 22.6% (19,031) | Ref | |

| South Atlantic | 22.1% (18,566) | 0.77 (0.73–0.81) | |

| Mid-west | 26.5% (22,345) | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | |

| South | 11.1% (9,313) | 0.8 (0.76–0.85) | |

| West | 17.8% (14,959) | 0.90 (0.86–0.95) | |

Also controlled for year of diagnosis, receipt of systemic therapy, race, education, and income

Multivariable logistic regression identified patient, tumor, and facility factors predictive of adjuvant RT (Table 1). Specifically, when examining patient factors, the data demonstrate an inverse relationship between patient age and the odds of receipt of adjuvant RT; when compared to women age 70–74 years, the adjusted odds ratio decreased from 0.65 for women aged 75–79 to 0.20 for women aged 85 years and older. Furthermore, sicker patients, represented by the Charlson–Deyo comorbidity score, were less likely to undergo adjuvant RT. In regard to tumor characteristics, higher grade tumors (adjusted OR 1.2 for moderately differentiated and 1.5 for poorly differentiated) and the presence of positive margins (adjusted OR 1.1) were also associated with an increased likelihood of receiving RT. However, there was no significant association between Her2neu status and receipt of adjuvant RT. Finally, multivariable analysis demonstrated the significance of facility-level factors with the receipt of radiation. After controlling for patient variables, women treated at comprehensive community, community or integrated facility were significantly more likely to undergo adjuvant RT when compared to those treated at an academic center (adjusted OR 1.3, 1.2, and 1.4, respectively). In addition, variation was observed both across regions of the country as well as over time. Year of diagnosis was strongly associated with receipt of radiation, with lower rates of radiation in the later years (p = < 0.0005).

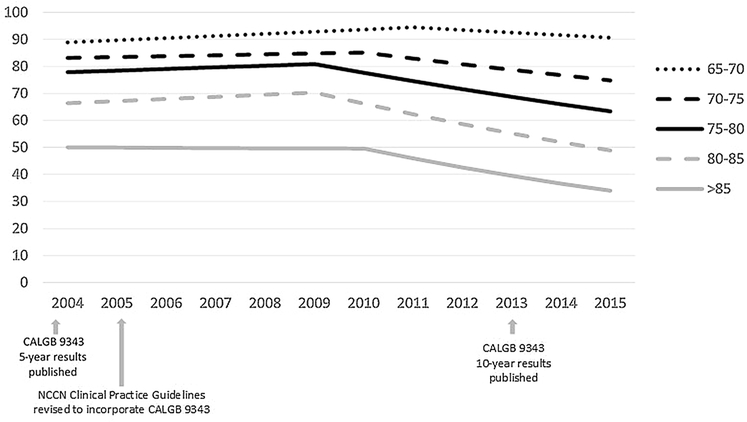

Confirming the findings of the multivariable analysis, joinpoint model estimates of temporal trends identified changes in the rate of receipt of adjuvant radiation therapy. For the overall cohort, the rate of adjuvant RT for women eligible for CALGB 9343 ranged from 77.2% in 2004 to 64.3% in 2015. Figure 2 presents model estimates of temporal trends in receipt of adjuvant radiation, stratified by patient age. Overall, while the rate of adjuvant RT use decreased for all age groups after 2009–2010, the rate of decline was more pronounced with increased age: aged 70–74 APC − 2.6 (95% CI − 3.1, − 2); aged 75–79 APC − 4.0 (95% CI − 5.1, − 2.8); aged 80–84 APC − 5.9 (95% CI − 7.6, − 4.2); aged > 85 APC − 7.3 (95% CI − 10.8, − 3.7). Receipt of adjuvant RT for patients age 85 years and greater dropped from 50.0% to 33.9% in 2004 and 2015, respectively. For this age group the model indicates one joinpoint in 2010, whereby utilization of adjuvant RT was stable from 2004–2010 (APC: − 0.2; 95% CI − 3.5, 3.3) with a significant decrease in use after 2010 (APC − 7.3; 95% CI − 10.8, − 3.7). In comparison, 82.6% of patients aged 70 to 74 years received adjuvant RT in 2004 and this declined to 74.0% of patients in this age group by 2015. The model similarly indicated one joinpoint in 2010 for this age group, with a less pronounced decrease in use after 2010 (APC − 2.6, 95% CI − 3.1, − 2) when compared to women aged 85 or older.

Fig. 2.

Model estimates of temporal trends for receipt of adjuvant RT, stratified by age

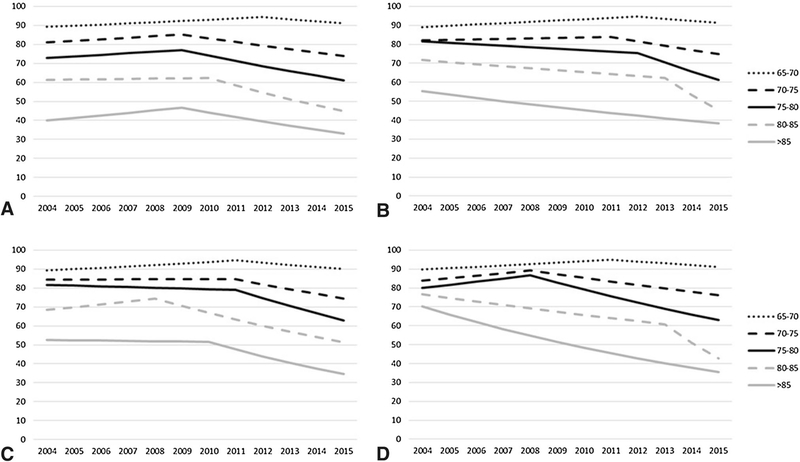

Results from these analyses demonstrate variation based not only on patient age but also by the type of facility at which they were treated (Fig. 3). The decline in receipt of adjuvant RT occurred earlier and was most pronounced in older women who received treatment at an academic facility (Fig. 3, panel A). For women treated at an academic center, the APC was − 5.6 (95% CI − 8.6, − 2.4) after 2009 for women aged 85 years and older, − 6.4 (95% CI − 9.0, − 3.8) after 2010 for women aged 80 − < 85 years, − 3.7 (95% CI − 5.6, − 1.9) after 2009 for women aged 75 − < 80, and − 2.4 (95% CI, − 3.1, − 1.6) after 2009 for women aged 70 − < 75. In contrast, at community facilities (Fig. 3, panel B) rates of RT declined much later (2011, 2012, and 2013 for age groups 70–74, 75–79, and 80–84 years, respectively).

Fig. 3.

Model estimates of temporal trends for receipt of adjuvant RT, stratified by age at a academic facilities, b community facilities, c comprehensive community facilities, and d integrated facilities

Discussions

Our analysis demonstrates decreased utilization of adjuvant RT following BCS for women over age 70 in the years following the publication of the CALGB 9343 study results. The overall decrease in the use of RT suggests a slow diffusion of the new data and clinical practice guidelines into broad clinical practice. However, changes in the use of RT was not observed uniformly across the cohort, as older women with comorbidities and those with low grade tumors were more likely to forgo RT. Our findings support our initial hypothesis that providers are using a tailored approach to incorporating CALGB 9343 findings into their clinical practice. Importantly, our findings may also reflect the influence of patient preference on treatment decision-making.

The existing randomized controlled trials that have examined the benefits associated with RT after BCS for older women have consistently demonstrated equivalent survival with or without RT [1, 2, 4, 5]. The equivalent survival is what led to the revision of clinical practice guidelines to allow for the omission of RT following BCS in certain groups of older women [3]. However, it is important to acknowledge that the trials also consistently demonstrated a significant decrease in the rate of local–regional recurrence with the use of RT. Although local–regional recurrence rarely impacts overall survival for early-stage patients [24], it is a prioritized outcome for breast cancer patients and influences patients’ initial decision-making for mastectomy versus BCS [25]. It seems natural that older breast cancer survivors would also consider the absolute risk of a local–regional recurrence when deciding whether to forgo RT after BCS, making the decision for RT a patient-centered decision that relies heavily on an individual’s values.

Patients may also be choosing RT as an alternative to 5-years of endocrine therapy. All enrolled patients enrolled on CALGB 9343 were recommended to receive 5 years of tamoxifen. Adherence to endocrine therapy is generally good in the clinical trial setting where patients are closely monitored [26] However, adherence to endocrine therapy in routine clinical practice is highly variable and a substantial proportion of women stop their endocrine therapy early due to side-effects [27] One possible explanation for the persistent use of RT is that women may be choosing to undergo a limited course of RT delivered over weeks instead of endocrine therapy over 5 years, given data suggesting survival outcomes may be equivalent [28, 29]. This is an especially pertinent consideration with the increasing availability of accelerated partial breast irradiation and hypofractionated radiation courses. Overall, the preference-sensitive nature of the decision for RT after lumpectomy means that use of RT for some older women will persist, and a shared decision-making approach to decision-making that includes a balanced discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of RT for older women is critical.

We observed both patient demographic and disease-level variables to be associated with the use of RT. Factors that increase the likelihood of a local–regional recurrence (higher tumor grade and positive margin status) were associated with a higher likelihood of receiving RT. Factors that may suggest less overall benefit to the use of RT to prevent a local–regional recurrence, including advanced age and greater burden of medical comorbidities, were associated with a lower likelihood of receiving RT. Joinpoint analysis also demonstrated that the decline in use of RT occurred earlier for older women, suggesting that providers and their patients may be more willing to forego radiation in circumstances where they perceived there to be less overall benefit from RT; this suggests that the option of omission of RT in women > 70 years of age is being appropriately adopted. However, it is important to recognize that > 30% of women over 85 years of age received RT. Given that women over 85 years of age can expect 7 additional years of life [30], use of RT in this oldest cohort may still reflect patient-centered care for patients who perceived the benefit of RT to prevent a local–regional recurrence outweighed the risk. This is especially true for the 20% of women > 85 who pursued partial breast radiation as a possible compromise between no RT and a complete course of whole breast irradiation [10, 31].

Although the importance of patient-level factors and patient choice in determining receipt of RT is clear, we also observed system-level variation that suggests that opportunities to de-escalate care exists. We observed increased use of RT at community facilities and comprehensive community centers when compared to academic centers, as well as by geographic region. This discrepancy exists both in absolute percentage in overall use as well as the time frame over which the decline occurred. While use of adjuvant RT was similar between facilities for women younger than 70, what is most striking is that receipt of RT decreased as many as 3 years earlier for older women treated at academic centers as compared to community hospitals. This may reflect increased patient participation in clinical trials addressing the question of RT in elderly women at the academic sites. Alternatively, this may reflect more rapid uptake of research findings at academic sites due to increased awareness, possibly through meeting attendance or professional societies. We are not able to determine through the NCDB data set who ultimately made the decision to forgo RT (surgeon, radiation oncologist, patient) or if older patients are even being referred to radiation oncology for a discussion of the potential benefits and risks associated with RT. This has important implications for potential de-implementation efforts in that we cannot know if efforts to improve guideline concordant care delivery should be targeted at the patient (e.g., educational brochures), surgeons (e.g., communication workshops to promote shared decision-making), or radiation oncologists (e.g., educational seminars, audit feedback) [16]. This gap highlights an obvious area for future cancer care delivery research [32].

Our study is strengthened by the large number of cancer patients included from diverse facilities across the USA. However, some limitations exist. We do not have data regarding cancer recurrence that would allow us to determine if the decision to defer radiation therapy had a negative clinical outcome. We observed that older women undergoing radiation were more likely to receive partial breast radiation than younger women. However, limitations and inconsistencies in the radiation fields reported within NCDB limited our ability to more discretely describe the type of radiation received. Although we used duration of treatment as a surrogate for partial breast versus whole breast radiation, we cannot be sure what was being targeted with the radiation course. Due to significant missingness in the dataset, we did not include the variable describing the travel distance between patient and treatment facility. This information could provide valuable insight into the etiology of the facility-level variation observed. Finally, we are unable to definitively determine through this registry database the influence of provider recommendation versus patient preference on the receipt of RT.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that rate of utilization of adjuvant RT following BCS for women age 70 years and older is declining. Patient-level variation in receipt of RT likely reflects patient-centered care, with tailored implementation of the CALGB 9343 findings based on patients’ life expectancy, risk of local–regional recurrence, and patient preference. However, variation by geographic region and facility type suggests opportunities to improve cancer care delivery by de-implementing the routine use of RT for older women. De-escalating care that has been highly prevalent in clinical practice is challenging, especially for a preference-sensitive decision such as this. Future studies should focus on the specific barriers and facilitators to de-implementation of RT after BCS for women over age 70 in order to inform future interventions designed to decrease the routine use of RT.

Acknowledgments

Funding Dr. Taylor is supported by a training award from the National Institutes of Health (T32CA090217). Dr. Neuman received support from the BIRCWH Scholars Program (K12 HD055894).

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest Lee Wilke is a minority stock owner and founder of Elucent Medical. Caprice Greenberg is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson.

Ethical approval This project is considered to be exempt by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1.Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Berry D et al. (2004) Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women 70 years of age or older with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 351(10):971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Bellon JR et al. (2013) Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 years or older with early breast cancer: long-term follow-up of CALGB 9343. J Clin Oncol 31(19):2382–2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Network. NCC. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Breast Cancer (2019) Version 2.2019 Accessed 5 Aug 2019

- 4.Kunkler IH, Williams LJ, Jack WJ, Cameron DA, Dixon JM (2015) Breast-conserving surgery with or without irradiation in women aged 65 years or older with early breast cancer (PRIME II): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 16(3):266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potter R, Gnant M, Kwasny W et al. (2007) Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen or anastrozole with or without whole breast irradiation in women with favorable early breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 68(2):334–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soulos PR, Yu JB, Roberts KB et al. (2012) Assessing the impact of a cooperative group trial on breast cancer care in the medicare population. J Clin Oncol 30(14):1601–1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palta M, Palta P, Bhavsar NA, Horton JK, Blitzblau RC (2015) The use of adjuvant radiotherapy in elderly patients with early-stage breast cancer: changes in practice patterns after publication of Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9343. Cancer 121(2):188–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutter CE, Lester-Coll NH, Mancini BR et al. (2015) The evolving role of adjuvant radiotherapy for elderly women with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer 121(14):2331–2340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu QD, Zhou M, Medeiros KL, Peddi P, Wu XC (2017) Impact of CALGB 9343 trial and sociodemographic variation on patterns of adjuvant radiation therapy practice for elderly women (%3e/=70 Years) with stage I, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: analysis of the national cancer data base. Anticancer Res 37(10):5585–5594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reyes SA, Williams AD, Arlow RL, et al. (2019) Changing practice patterns of adjuvant radiation among elderly women with early stage breast cancer in the United States from 2004 to 2014. Breast J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luu C, Goldstein L, Goldner B, Schoellhammer HF, Chen SL (2013) Trends in radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in elderly patients with early-stage breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 20(10):3266–3273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCormick B, Ottesen RA, Hughes ME et al. (2014) Impact of guideline changes on use or omission of radiation in the elderly with early breast cancer: practice patterns at National Comprehensive Cancer Network institutions. J Am Coll Surg 219(4):796–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downs-Canner S, Zabor EC, Wind T et al. (2019) Radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery in women 70 years of age and older: how wisely do we choose? Ann Surg Oncol 26(4):969–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christian N, Heelan Gladden A, Friedman C, et al. (2019) Increasing omission of radiation therapy and sentinel node biopsy in elderly patients with early stage, hormone-positive breast cancer. Breast J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paulsson AK, Fowble B, Lazar AA, Park C, Sherertz T. (2019) Radiotherapy utilization for patients over age 60 with early stage breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norton WE, Chambers DA, Kramer BS (2019) Conceptualizing de-implementation in cancer care delivery. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 37(2):93–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Commission on Cancer. Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards. In: Chicago, IL: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bekelman JE, Sylwestrzak G, Barron J et al. (2014) Uptake and costs of hypofractionated vs conventional whole breast irradiation after breast conserving surgery in the United States, 2008–2013. JAMA 312(23):2542–2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA (1992) Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 45(6):613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clegg LX, Hankey BF, Tiwari R, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK (2009) Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat Med 28(29):3670–3682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frasier LL, Holden S, Holden T et al. (2016) Temporal trends in postmastectomy radiation therapy and breast reconstruction associated with changes in national comprehensive cancer network guidelines. JAMA Onco 2(1):95–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schumacher JR, Taylor LJ, Tucholka JL et al. (2017) Socioeconomic factors associated with post-mastectomy immediate reconstruction in a contemporary cohort of breast cancer survivors. Ann Surg Oncol 24(10):3017–3023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu D, Katanoda K, Marugame T, Sobue T (2009) A Joinpoint regression analysis of long-term trends in cancer mortality in Japan (1958–2004). Int J Cancer 124(2):443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S et al. (2005) Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 366(9503):2087–2106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee CN, Chang Y, Adimorah N et al. (2012) Decision making about surgery for early-stage breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg 214(1):1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chlebowski RT, Kim J, Haque R (2014) Adherence to endocrine therapy in breast cancer adjuvant and prevention settings. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 7(4):378–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK, Carpentier MY, Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW (2012) Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 134(2):459–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ward MC, Vicini F, Chadha M et al. (2019) Radiation therapy without hormone therapy for women age 70 or above with lowrisk early breast cancer: a microsimulation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 105(2):296–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buszek SM, Lin HY, Bedrosian I et al. (2019) Lumpectomy plus hormone or radiation therapy alone for women aged 70 years or older with hormone receptor-positive early stage breast cancer in the modern era: an analysis of the national cancer database. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 105(4):795–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arias E, Xu J. United States Life Tables (2017) In: national center for health statistics, ed. Vol 68 Hyattsville, MD: 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Genebes C, Chand ME, Gal J et al. (2014) Accelerated partial breast irradiation in the elderly: 5-year results of high-dose rate multi-catheter brachytherapy. Radiat Oncol 9:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kent EE, Mitchell SA, Castro KM et al. (2015) Cancer care delivery research: building the evidence base to support practice change in community oncology. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 33(24):2705–2711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]