Abstract

Objective: To examine the effectiveness of four doses of psychostimulant medication, combining extended-release methylphenidate (ER-MPH) in the morning with immediate-release MPH (IR-MPH) in the afternoon, on cognitive task performance.

Method: The sample comprised 24 children (19 boys and 5 girls) who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria for an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) on the Autism Diagnostic Interview-R and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, and had significant symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). This sample consisted of elementary school-age, community-based children (mean chronological age = 8.8 years, SD = 1.7; mean intelligence quotient = 85; SD = 16.8). Effects of placebo and three dose levels of ER-MPH (containing 0.21, 0.35, and 0.48 mg/kg equivalent of IR-MPH) on cognitive task performance were compared using a within-subject, crossover, placebo-controlled design. Each of the four MPH dosing regimens (placebo, low-dose MPH, medium-dose MPH, and high-dose MPH) was administered for 1 week; the dosing order was counterbalanced across children.

Results: MPH treatment was associated with significant performance gains on cognitive tasks tapping sustained attention, selective attention, and impulsivity/inhibition. Dose/response was generally linear in the dose range studied, with no evidence of deterioration in performance at higher MPH doses in the dose range studied.

Conclusion: The results of this study suggest that MPH formulations are associated with significant improvements on cognitive task performance in children with ASD and ADHD.

Keywords: ASD, ADHD, stimulants, cognitive tasks

Introduction

In recent years, the prevalence rate of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the pediatric population has reportedly reached 1 in 68—nearly 2% of children (CDC 2014). These children with ASD are known to be at high risk for emotional and behavioral disorders (e.g., Pearson et al. 2006, 2012; Simonoff et al. 2008; Lecavalier et al. 2019). A growing literature suggests that 28%–87% of children with ASD have sufficient symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity to meet the diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Frazier et al. 2001; Goldstein and Schwebach 2004; Sturm et al. 2004; Lecavalier 2006; Lee and Ousley 2006; Leyfer et al. 2006; Pearson et al. 2006; Reiersen et al. 2007; Simonoff et al. 2008; Sinzig et al. 2009; Ponde et al. 2010; Ames & White 2011; Amr et al. 2012; Mansour et al. 2017). In addition to the significant psychological and educational burden imposed by the comorbidity of ASD and ADHD, these children incur 30% higher medical expenditures than other children with ASD—and the mean medical expenditures of children with ASD alone were six times the rate of children without ASD (Peacock et al. 2012).

One contribution to these costs is the growing practice of treating behavioral and emotional concerns in individuals with ASD with psychotropic medications. Some reports have suggested that 27%–70% of individuals with ASD are treated with these medications (e.g., Aman et al. 2005; Esbensen et al. 2009; Frazier et al. 2011; Coury et al. 2012), including 16%–34% taking psychostimulants (Witwer and Lecavalier 2005; Frazier et al. 2011; Pringle et al. 2012; Dalsgaard et al. 2013; Hsia et al. 2014; Mire et al. 2014; Antshel et al. 2016). This trend is accelerating: Dalsgaard et al. (2013) noted a fivefold increase in ADHD medications between 2003 and 2010 in children and adolescents with ASD and ADHD in a Danish registry study. Furthermore, children and adolescents with ASD who are medicated are likely to stay medicated over time (Esbensen et al. 2009).

Despite the growing trend for substantial numbers of children with ASD and ADHD to be treated with stimulant medication, relatively few controlled studies have been conducted assessing the behavioral—and especially cognitive—effects of stimulant medication in this population. Early studies (e.g., Campbell et al. 1972; Campbell 1975) suggested that stimulants were associated with concerning side effects such as increased irritability, aggression, and stereotypic behavior. Case studies of psychostimulant response in children with ASD further noted concerns with agitation, stereotypies, exacerbation of symptoms such as trichotillomania and dysphoria, and induction of psychotic symptoms (Sporn and Pinsker 1981; Schmidt 1982; Volkmar et al. 1985; Realmuto et al. 1989; Holttum et al. 1994).

More recent investigations have suggested that stimulant treatment in children with ASD and symptoms of ADHD may have more favorable outcomes. Stimulant treatment has been associated with gains in attention and reduced symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity (e.g., Hoshino et al. 1977; Geller et al. 1981; Vitriol and Farber 1981; Birmaher et al. 1988; Strayhorn et al. 1988; Quintana et al. 1995; Aman 1996; Handen et al. 2000; DiMartino et al. 2004; Santosh, et al. 2006; Nickels et al. 2008; Pearson et al. 2013). Simonoff et al. (2013) noted that methylphenidate (MPH) was effective in improving symptoms of ADHD in a sample of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities who had significant ASD symptomatology (the average Social Communication Questionnaire score for the sample was >15). Ghuman et al. (2009) noted MPH-related improvement in ADHD symptoms in preschool children with ASD, and also noted that their response was “more subtle and variable” than older and typically developing children with ADHD.

A similar finding was noted by the Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network (2005) in their double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of immediate-release MPH (IR-MPH). Although MPH was found to decrease hyperactivity and inattention, only 48% of children with ASD (Autistic Disorder Asperger's and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified [PDD-NOS]) responded positively to MPH, as opposed to ∼75% of children with ADHD in the general pediatric population—and the magnitude of improvement was smaller (RUPP 2005). In addition, 18% of the children in the RUPP study discontinued treatment due to side effects (mainly irritability), in contrast to <4% of children with ADHD (who did not have ASD) in the NIMH Multimodal Treatment of ADHD (MTA) (MTA Cooperative Group 1999). Despite the cautionary findings from the RUPP study (lower positive response rate and higher rate of side effects), MPH treatment in the RUPP study children was associated with gains in social communication (Posey et al. 2007) and self-regulation (Jahromi et al. 2009).

This literature is based upon studies of IR-MPH, but two recent studies have noted that extended-release formulations of MPH were effective in treating symptoms of ADHD in children with ASD. Pearson et al. (2013) found successive improvements with higher MPH dosing regimens in parent and teacher ratings of ADHD and closely related behaviors, (e.g., oppositional behavior)—without exacerbation in stereotypies. Kim et al. (2017) also found that an extended-release formulation of MPH was effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, again in a linear dose/response curve. Although findings such as these suggest that higher doses of stimulant treatment are associated with better outcomes, older studies (e.g., Sprague and Sleator 1977; Gan and Cantwell 1982) with participants who did not have ASD reported a curvilinear response to stimulant medication—lower doses produced initial improvements relative to placebo, followed by declines at higher doses (both of these studies used a high MPH dose of 1.0 mg/kg). It is also interesting to note that studies based on randomized-controlled trials with N's ≥ 10 tended to find improvements with MPH treatment, for example, Quintana et al. (1995; n = 10), Handen et al. (2000; n = 13), RUPP (2000; n = 72), Ghuman et al. (2009; n = 14), Simonoff et al. (2013; n = 122), Pearson et al. (2013; n = 24), and Kim et al. (2017; n = 27).

To our knowledge, these two studies (Pearson et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2017) are the only reports in the literature assessing the effectiveness of long-acting formulations of psychostimulants in treating symptoms of ADHD in children with ASD—despite the fact that long-acting formulations are now the current standard of practice in the field (AACAP 2007). The overall purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of psychostimulant treatment with ER-MPH on cognitive task performance in children with ASD and significant symptoms of ADHD. This report supplements our previous report on the behavioral effects of MPH in the same population of children with ASD+ADHD (Pearson et al. 2013). Our goals were to determine if (1) ER-MPH was associated with improvements on cognitive tasks tapping sustained attention, selective attention, and impulsivity/inhibition, and (2) the MPH dose/response curve was linear (i.e., higher MPH doses are associated with further improvements in cognitive functioning), or curvilinear (an initial cognitive improvement with MPH, followed by declines at higher doses).

Methods

Participants

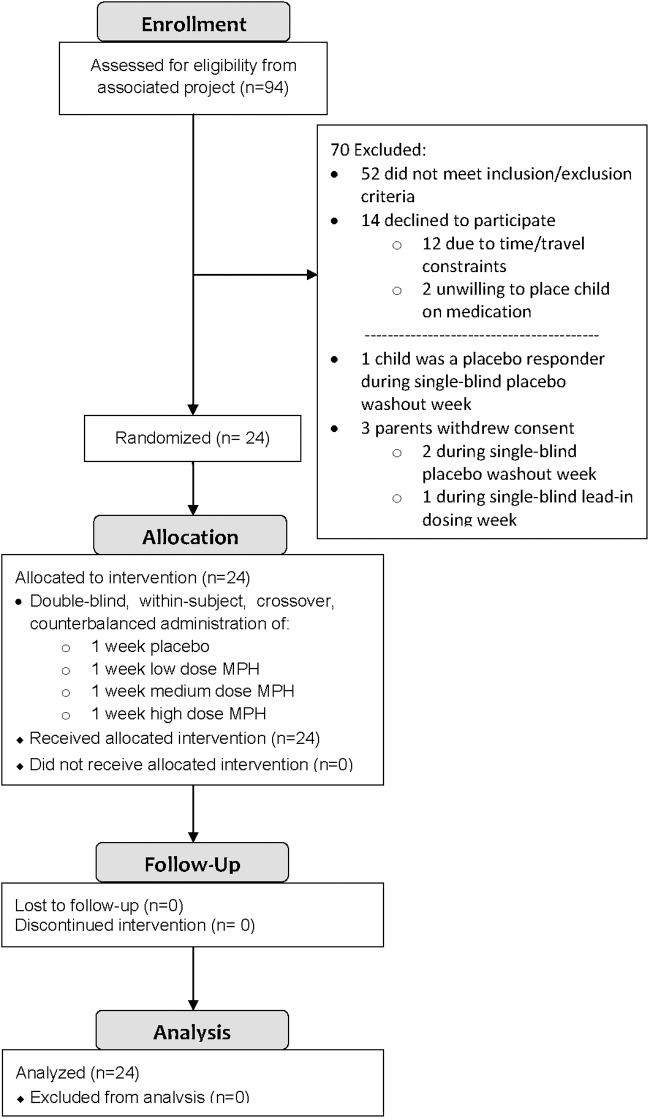

As has been reported previously (Pearson et al. 2013), and as noted in Figure 1, 24 children (19 boys and 5 girls) with ASD and symptoms of ADHD participated in this study. As indicated in Table 1, the mean chronological age of the sample was 8.8 years (SD = 1.6; range 7–12 years), and the mean Full Scale IQ (Stanford-Binet 5th Ed. [SB5]) (Roid 2003) was 85.0 (SD = 16.8). The racial/ethnic breakdown of these children was as following: 18 Caucasian (including 5 children of Hispanic ethnicity), 4 African American, 1 Asian, and 1 multiple races. Their mean Hollingshead 4-factor social class was 1.7 (SD = 0.9; Hollingshead 1975). The mean education level was 15.8 (SD = 2.3) years for mothers and 17.2 (SD = 3.1) years for fathers. These children were assessed using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-R (ADI-R) (Rutter et al. 2003), the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord et al. 1999), a clinical interview, clinic observation, and record review by two licensed psychologists (D.A.P. and K.A.L.) who are both highly experienced in the assessment and diagnosis of ASD, and who are certified as meeting research reliability on the ADI-R/ADOS. Nineteen (79%) children met the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000) criteria for autistic disorder, 3 (13%) had Asperger's disorder, and 2 (8%) had PDD-NOS.

FIG. 1.

Study recruitment and retention.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variable | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronological age (years) | 8.8 | 1.7 | 7.1–12.7 |

| Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scale, 5th Ed. | |||

| Verbal IQ | 80.1 | 19.7 | 48–115 |

| Nonverbal IQ | 90.8 | 15.2 | 50–118 |

| Full Scale IQ | 85.0 | 16.8 | 46–112 |

| Verbal age equivalent (months) | 79.71 | 25.1 | 43–143 |

| Nonverbal age equivalent (months) | 89.79 | 23.2 | 64–142 |

| Full Scale age equivalent (months) | 84.04 | 23.5 | 52–145 |

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-II | |||

| Communication domain | 77.6 | 7.2 | 62–94 |

| Daily living skills domain | 80.3 | 8.0 | 61–97 |

| Socialization domain | 76.7 | 6.8 | 64–89 |

| Vineland composite | 76.4 | 6.1 | 61–89 |

| Social Communication Questionnaire | 23.4 | 5.2 | 14–35 |

| Hollingshead 4-factor social class | 1.7 | 0.9 | 1–4 |

| Hollingshead 4-factor SES score | 52.3 | 10.8 | 29–66 |

| Parent educational level (no. of years) | |||

| Father | 17.2 | 3.1 | 12–25 |

| Mother | 15.8 | 2.3 | 12–21 |

SES, socioeconomic class.

As determined by interviewing parents using the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents-IV (DICA-IV) (Reich et al. 1997), 19 children met DSM-IV-TR criteria for ADHD-Combined Type, and five for ADHD-Predominantly Inattentive Type (ignoring the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Ed. Text Revision [DSM-IV-TR] exclusion of an ADHD diagnosis in a child with ASD). Severity of ADHD symptomatology was measured using the ADHD Index from Conners Parent Rating Scale-Revised (mean CPRS-R ADHD Index T-score = 76.1, SD = 6.7) (Conners 1997) and the Conners Teacher Rating Scale-Revised (mean CTRS-R ADHD Index T-score = 67.2, SD = 8.7) (Conners 1997). The ADHD diagnosis was confirmed by clinic observation and by record review by two licensed psychologists (D.A.P. and K.A.L.) who are highly experienced in diagnosing ADHD. In addition, the DICA-IV (Reich et al. 1997) revealed that five children also met DSM-IV-TR criteria for oppositional defiant disorder, two for obsessive compulsive disorder, and one for separation anxiety. Exclusion criteria included serious neurological disorders (e.g., stroke, seizures), Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, Tourette syndrome, psychosis, and mood disorders. Thirteen children had previously taken stimulant medication, which was discontinued ≥1 week before entry into the trial (mean discontinuation before trial = 63 days, range: 7–547 days). Seven children were stable on long-term (>3 months) nonstimulant medications that they continued (at a constant dose) during the trial: risperidone (n = 3), aripiprazole (n = 1), sertraline (n = 1), bupropion (n = 1), and trazodone (n = 1). All children were recruited from the community and lived at home; they were recruited from special education classrooms of a large metropolitan public school district. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and from participants older than 12 years, and assent was obtained from the younger children. The study was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Design

A within-subject, crossover, placebo-controlled design was used to assess the cognitive effects of MPH. Before starting the drug trial, all children received a single-blind week of placebo (study personnel were unblinded), during which the medication-taking regimen was established both at home and at school. As an extra safety precaution following the single-blind placebo week, each child received a single-blind week of “lead-in dosing,” during which he or she was given 2 days each of low, medium, and high MPH doses that he or she would receive in the double-blind phase of the study, in ascending order. The children were seen by the study physician (C.W.S.) and the primary study psychologist (D.A.P.) at the end of this lead-in dosing week to insure that they tolerated the three doses well; all 24 children were cleared to take all three doses of the medication in the double-blind phase. Although all 24 children completed the trial, 5 of the 24 children discontinued the afternoon IR-MPH dose due to behavior concerns in late afternoon/evening (irritability: n = 5; decreased sleep: n = 2; increased stereotypic behaviors: n = 2).

During the actual medication trial, each child received 1 week each of the four MPH dosing regimens (placebo, low-dose MPH, medium-dose MPH, and high-dose MPH). The order of dosage administration was counterbalanced across children using a digram-balanced Latin squares procedure, which controls for both order and sequence (Wagenarr 1969). Dosing was based on body weight; doses were similar to those used in the MTA and the RUPP MPH trials. As seen in Table 2, the children received Ritalin LA (extended-release MPH [ER-MPH]) at breakfast and IR-MPH in the afternoon. In an attempt to minimize side effects, no child received a dose greater than the equivalent of an IR-MPH dose of 0.6 mg/kg, and no child's total daily dose exceeded the equivalent of an IR-MPH BID dose of 50 mg. As seen in Table 2, the mean IR-MPH per dose equivalents of the Ritalin LA (given in the morning) were 0.21 mg/kg MPH in the low-dose condition, 0.35 mg/kg in medium dose, and 0.48 mg/kg in the high dose. The IR-MPH dose (given in the afternoon) was sculpted to be approximately half of each single-dose equivalent of the morning's Ritalin LA. Ritalin LA was selected as the ER-MPH formulation because its pharmacokinetics mirrored the BID dosing of IR-MPH used in the morning/noon dosing of the RUPP study, its extended-release formulation improved ease of administration and hence compliance, and its beaded technology allowed for sprinkling the beads on applesauce for children with oral apraxia (parents sprinkled the beads for eight children). The study medication was prepared by the UT Psychiatry Research Pharmacy: the Ritalin LA beads were mixed with (inert) placebo beads and placed in two opaque gelatin capsules, and the white generic IR-MPH was crushed and mixed with cornstarch and placed in two Size 1 gelatin capsules (for swallowing ease). All study personnel with patient contact were blind with respect to dosages given during the drug trial.

Table 2.

Extended-Release Methylphenidate and Immediate-Release Methylphenidate Dosing Levels, by Child's Body Weight

| MPH dose regimen | AM dose: Ritalin LA | PM dose: IR-MPH |

|---|---|---|

| Lower body weight group (20–24 kg) | ||

| Low dose | 10 mg Ritalin LA | 2.5 mg IR-MPH |

| Medium dose | 15 mg Ritalin LA | 5 mg IR-MPH |

| High dose | 20 mg Ritalin LA | 5 mg IR-MPH |

| Medium body weight group (25–33 kg) | ||

| Low dose | 10 mg Ritalin LA | 5 mg IR-MPH |

| Medium dose | 20 mg Ritalin LA | 5 mg IR-MPH |

| High dose | 30 mg Ritalin LA | 10 mg IR-MPH |

| Larger body weight group (34–59 kg) | ||

| Low dose | 20 mg Ritalin LA | 5 mg IR-MPH |

| Medium dose | 30 mg Ritalin LA | 10 mg IR-MPH |

| High dose | 40 mg Ritalin LA | 10 mg IR-MPH |

| MPH dosing levels in mg/kg IR-MPH dose equivalents across all body weight groups | ||

|---|---|---|

| MPH dosing regimen | First MPH dose: mg/kg equivalent of IR-MPH (BID) | Later PM dose: IR-MPH |

| Low dose |

0.21 mg/kg |

0.14 mg/kg |

| Medium dose |

0.35 mg/kg |

0.24 mg/kg |

| High dose | 0.48 mg/kg | 0.27 mg/kg |

IR-MPH, immediate-release MPH; MPH, methylphenidate.

Procedure

Participants were recruited to the trial after completing assessment that included a neuropsychological test battery (including the SB5) and psychiatric interview. Participants were given a physical examination by the study physician (C.W.S.) to confirm medical eligibility to take MPH. Each child was given a brief vision and hearing test to ensure that they could see and hear the cognitive task stimuli. The children were seen at the end of the (single-blind) placebo baseline week, the end of the lead-in dosing week, and at the end of each week of the drug trial for both a medication check with the study physician (C.W.S.) and for an interview with the primary study psychologist (D.A.P.).

The cognitive tasks used in this trial were selected on the basis of their ability to discriminate children with and without ADHD, their appropriateness for the cognitive developmental level of the children, and for their sensitivity to MPH treatment. They were performed at the end of each week of the drug trial; medication was administered at the clinic upon arrival (first thing in the morning), and cognitive testing started ∼60 minutes later. Thus, the children received their cognitive testing while under the influence of the ER-MPH. Cognitive task order was randomized across subjects, and this order was held constant across all 4 weeks of the drug trial for each participant. Before each task, the children were given practice trials, during which time they were given feedback on their performance. With the exception of the Matching Familiar Figures Test (MFFT), no feedback was given during the actual test trials, but the child was redirected to task if she or he looked away or spoke. Each weekly test session lasted ∼90 minutes, including short breaks. Thus, the cognitive testing was carried out when the MPH had reached therapeutic blood levels, and before concentrations had time to decline.

Instruments

Sustained attention

Continuous performance test

A modified version of the continuous performance test (CPT) (Rosvold et al. 1956) was used to examine sustained attention. Participants were presented with a series of black and white familiar pictures on a computer screen that were presented one at a time (stimuli: cat, bicycle, duck, tree, cow, banana, zebra, apple, truck, fish, house, and a witch). They were instructed to press the response key only when they saw the witch (i.e., the target). There were four blocks of 100 stimuli (including 15% targets); each picture was presented for 200 msec, and the interstimulus interval was 1500 msec. The task took ∼12 minutes to run. CPT performance was assessed by the number of omission errors, commission errors, and reaction time. The CPT differentiates children with and without ADHD in the general pediatric population (e.g., Sykes et al. 1971; Riccio et al. 2001; Epstein et al. 2003), as well as children with and without ADHD who have intellectual disabilities (Aman et al. 1991b, 1993; Pearson et al. 1996, 2004b).

Selective attention

Speeded classification task

The speeded classification task (SCT) (Strutt et al. 1975) is a computerized measure of visual selective attention in which children sort stimuli on the basis of a binary dimension. The dimension could be a shape (a circle or a square), a line (horizontal or vertical), or a star (presented above or below the figure). The relevant dimension could appear by itself (e.g., just a circle), or with one or two distracting dimensions (e.g., a circle with a horizontal line drawn through it and a star above it). The test stimulus appeared at the center of the computer screen; children matched this stimulus with one of the two sample stimuli at the bottom corners of the screen (e.g., a circle in one corner, and a square in the other). Children responded by touching the matching sample stimulus, using a computer touch screen (TouchWindow; Edmark Corporation, Redmond, WA). SCT performance was assessed by examining sorting errors and reaction time. The SCT discriminates children with and without ADHD of normal intelligence (Rosenthal and Allen 1980), as well as children with and without ADHD who have intellectual disabilities (Pearson et al. 1996). It is also sensitive to MPH treatment in the latter group (Pearson et al. 2004b).

Selective listening task

The stimuli used for the selective listening task were taken from the competing sentences subtest of the Pediatric Speech Intelligibility Test (Jerger 1987). This computerized version presented stimuli (comprising spoken sentences) through headphones, using Adobe Audition to play the stimuli and control the parameters. Sentences were presented simultaneously in both ears, with one ear being the target ear (i.e., the ear that received the target sentence), while the other ear received the distractor (i.e., nontarget) sentence. Children were told to touch one of five pictures on a card that matched the target sentence. The distractor sentences did not have pictures represented on the card. For each of the two ears, children were first presented with a series of five practice trials, in which a target sentence (e.g., “The bear is brushing his hair”) was presented by itself to one ear. They then did a second set of five practice trials in which they heard the competing sentences. They then did 20 trials in the real test. They then repeated this sequence for the other ear. The children were told which ear was the target ear verbally and this was also indicated nonverbally (by tapping the appropriate ear of the headphones). Performance was measured by correct target identifications, omission errors, perseveration errors (selecting the picture from the previous trial), and random errors (selecting a response that was not presented to either ear). Before doing the task the first time, the children received a hearing screen to ensure that they could hear the stimuli adequately. Selective listening tasks differentiate children with and without ADHD in the general pediatric population (Prior et al. 1985; Pearson et al. 1991), and have been found to be sensitive to MPH treatment in children with ADHD who have intellectual disabilities (Pearson et al. 2004b).

Impulsivity/inhibition

Delay of gratification task

This task, adapted from the preschool delay task of the Gordon Diagnostic System (Gordon 1983), measures the ability to suppress or delay impulsive behavioral responses. Children were told that a star would appear on the computer screen if they waited “long enough” to press a response key. If a child responded sooner than 4 seconds after their previous response, they did not earn a star, and the 4-second counter restarted. Children performed one block as practice, and then four 92-second blocks during the actual test. Performance was measured by the number of correct responses and the efficiency ratio (no. of correct responses/total no. of responses). The delay of gratification differentiates children with and without ADHD in the general pediatric population (McClure and Gordon 1984). It has also been found to be sensitive to MPH treatment in these children (Hall and Kataria 1992), as well as in children with ADHD who have intellectual disabilities (Pearson et al. 2004b).

Matching Familiar Figures Test

This task consisted of a computerized version of the Kagan et al. (1964) MFFT task, in which the child saw a test stimulus picture at the top of the computer screen, along with six alternatives (one of which matched the test stimulus) further down on the screen. Participants were told to select the picture below that matched the test stimulus above. There were two practice items (mug, ruler), followed by 23 experimental items (e.g., line drawings of a house, scissors, telephone, teddy bear, tree, leaf, cat, coat). Incorrect responses resulted in a synthesized voice (D.M.L.) saying “try again,” while correct responses resulted in the same voice saying “that's right.” Performance was measured by matching errors and reaction time. The MFFT discriminates children with and without ADHD in the general pediatric population (e.g., Rapport and Kelley 1993). It has also been found to be sensitive to MPH treatment in these children (Campbell et al. 1971) and in children with ADHD and intellectual disabilities (Aman et al. 1991b; Pearson et al. 2004b).

Stop signal task

The stop signal task (SST) (Schachar et al. 1993) is a measure of motor response inhibition, involving a choice reaction time task and a stop task. The choice reaction time task (go task) involves two visual stimuli, either X or O, presented in the middle of a computer screen. On 75% of the trials (the “go trials”), the children were told to respond as quickly and accurately as possible by pressing the correct button corresponding to the letter on the screen. On 25% of the trials, the child was given a “stop” signal (a tone) telling him/her not to respond to the choice reaction time task (i.e., if the stimulus at the middle of the screen was an X or an O). The time between the visual stimulus and the stop stimulus is the stop signal delay. Short stop signal delays increase the probability of inhibiting (e.g., it is easier to stop a prepotent response earlier than later), while longer delays increase the probability of responding. The stop signal delay was set initially to 250 msec (i.e., it came on 250 msec after the onset of the go stimulus), but was dynamically adjusted according to the participant's response. If a particular trial was stopped when a stop signal was presented, the delay was increased by 50 msec on the subsequent stop signal trial (making it more difficult to stop on that trial). If the participant was unable to stop on a particular trial, the delay was decreased by 50 msec on the subsequent stop signal trial (making it easier to stop on that trial). This tracking algorithm converges on the delay that results in a probability of stopping of 0.5. We calculated stop signal reaction time (SSRT) using the imputation method (R.J. Schachar, personal communication, 6/12/2011; also outlined in Verbruggen et al. 2019). Total trial time is 3500 msec, with a 500 msec fixation, a 1000 msec go stimulus display (X or O), and a 2000 msec intertrial interval. Participants completed a practice block, followed by 6 experimental blocks with 32 trials per block. The duration of this task is 12 minutes. Primary outcome variables included “Go Accuracy” (correct responses on “go” trials), “Go RT” (reaction time on “go” trials), “Stop Accuracy” (correct responses on “stop” trials), SSRT, and the average stop signal delay over trials. Children with ADHD are less able than their non-ADHD peers to successfully inhibit when given the stop signal, as indicated by a longer SSRT (Schachar et al. 1993; Lipszyc and Schachar 2010). The SSRT had been used to study inhibition in higher functioning children with ASD (Ozonoff and Strayer 1997) and has been found to be sensitive to MPH treatment in children with ADHD (Bedard et al. 2003).

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using an SPSS-PC (Version 21.0) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedure, with MPH dosage as the within-subjects variable. As has been found previously (e.g., Aman et al. 1991b; Pearson et al. 2004b), a number of our cognitive task variables had non-normal distributions. To increase the power and validity of ANOVA, variables whose distributions deviated substantially from normality were transformed using the appropriate transformation from the Tukey Ladder of Transformations (Winer et al. 1971). Specific transformations for variables with non-normal distributions are reported in Table 3. Inferential statistics are all reported on the transformed variables, however, nontransformed data are reported below for ease of interpretation. Because preliminary analyses revealed no significant effects of sex or dose order, these factors were dropped from subsequent analyses. For significant effects, follow-up trend analyses were performed to determine if dose/response was primarily linear, or if there was a curvilinear/quadratic component of trend (e.g., an initial improvement in cognitive performance from placebo to a low or medium dose, followed by declines in cognitive performance). Finally, for measures that demonstrated significant MPH dosage effects, a sequential Bonferroni post hoc analysis (Holm 1979) was used to determine which MPH doses were significantly different from one another (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 3.

Summary of Methylphenidate Dose Effect on Cognitive Tasks

| Task/variable | Transformation used | Placebo Mean (SD) | Low Mean (SD) | Medium Mean (SD) | High Mean (SD) | F | p | Source of significance | Significance of linear trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained attention task | |||||||||

| Continuous performance test (n = 24) | |||||||||

| Commissions | −1/sqrt (x + 1) | 2.75 (3.49) | 1.11 (1.91) | 1.18 (1.71) | 1.24 (2.27) | 4.63 | 0.005 | P:L, P:H | 0.005 |

| Omissions | −1/sqrt (x + 1) | 2.18 (2.01) | 1.49 (1.73) | 1.17 (1.77) | 0.99 (1.43) | 7.21 | <0.001 | P:L, P:M, P:H | <0.001 |

| Median RT | NA | 621 (113) | 582 (102) | 561 (85) | 552 (115) | 10.45 | <0.001 | P:L, P:M, P:H, L:H | <0.001 |

| Selective attention tasks | |||||||||

| Speeded classification task (n = 23) | |||||||||

| Sorting errors | log (x + 1) | 2.74 (2.04) | 2.18 (1.67) | 1.93 (1.50) | 1.74 (2.09) | 4.22 | 0.016 | P:L, P:H, L:H | 0.005 |

| Median RT | NA | 940 (279) | 875 (326) | 957 (362) | 934 (399) | 0.82 | 0.485 | ns | 0.788 |

| Selective listening task (n = 22) | |||||||||

| % Correct | exp(x) | 87.83 (18.40) | 91.33 (17.75) | 92.00 (16.96) | 94.42 (12.48) | 5.21 | 0.003 | P:M, P:H | 0.001 |

| Omission errors | −1*(1/x+c) | 0.22 (0.37) | 0.16 (0.34) | 0.10 (0.26) | 0.08 (0.17) | 3.49 | 0.030 | P:M, P:H, L:M | 0.017 |

| Perseveration errors | sqrt(x) | 0.08 (0.22) | 0.04 (0.09) | 0.05 (0.19) | 0.03 (0.12) | 0.664 | 0.577 | ns | 0.086 |

| Random errors | sqrt(x) | 0.31 (0.58) | 0.18 (0.46) | 0.26 (0.58) | 0.17 (0.46) | 2.94 | 0.039 | P:L, P:H | 0.047 |

| Inhibition/impulsivity tasks | |||||||||

| Delay of gratification (n = 24) | |||||||||

| Efficiency | x3 | 0.78 (0.20) | 0.82 (0.18) | 0.81 (0.19) | 0.85 (0.17) | 1.88 | 0.158 | P:H, M:H | 0.109 |

| Correct responses | NA | 10.38 (3.17) | 11.23 (2.56) | 11.59 (2.16) | 12.00 (2.54) | 4.34 | 0.007 | P:L, P:M, P:H | 0.005 |

| Matching Familiar Figures task (n = 19) | |||||||||

| Errors | NA | 13.79 (3.97) | 13.68 (4.03) | 12.74 (4.21) | 11.74 (5.24) | 2.33 | 0.085 | ns | 0.024 |

| Median RT | NA | 5433 (3971) | 4698 (3474) | 5993 (4551) | 5229 (3755) | 0.842 | 0.477 | ns | 0.827 |

| Stop signal task (n = 23) | |||||||||

| Go accuracy (%) | x3 | 89.49 (7.96) | 92.24 (8.41) | 93.97 (5.74) | 94.90 (3.95) | 7.40 | <0.001 | P:L, P:M, P:H | 0.000 |

| Stop accuracy (%) | x3 | 51.94 (15.16) | 56.37 (10.73) | 55.06 (11.91) | 56.60 (10.72) | 1.65 | 0.184 | ns | 0.103 |

| Go RT (msec) | NA | 1040.38 (255.71) | 949.47 (283.82) | 1014.65 (202.70) | 979.23 (274.33) | 2.28 | 0.087 | P:L, P:H | 0.135 |

| SSRT | ln(x) | 550.27 (392.97) | 426.55 (234.14) | 398.32 (240.01) | 409.13 (253.10) | 2.36 | 0.079 | P:L, P:M, P:H | 0.048 |

| Stop signal delay | NA | 436.68 (212.00) | 468.32 (173.08) | 548.33 (216.35) | 494.22 (180.33) | 3.38 | 0.023 | P:M, L:M | 0.078 |

Bold values are statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05).

P:L, placebo and low dose MPH are statistically different from each other; P:M, placebo and medium dose MPH are statistically different from each other; P:H, placebo and high dose MPH are statistically different from each other; L:M, low and medium dose MPH are statistically different from each other; L:H, low and high dose MPH are statistically different from each other; NA, not applicable (no transformation was used); ns, not significant (p > .05); RT, reaction time (msec); SSRT, stop signal RT.

Results

Cognitive task performance at each of the MPH conditions is summarized in Table 3. If significant differences emerged between MPH doses, the source(s) of that significance (i.e., which doses were significantly different from each other) are also noted. Finally, the significance of the linear component of trend is also reported in Table 3. (No significant curvilinear components of trend in MPH response were found for any variables in any of the cognitive tasks.) Because no interactions with MPH dose level were significant for any of the task factors (e.g., MPH dose level by block number on the CPT), only the effects of MPH dose are reported below.

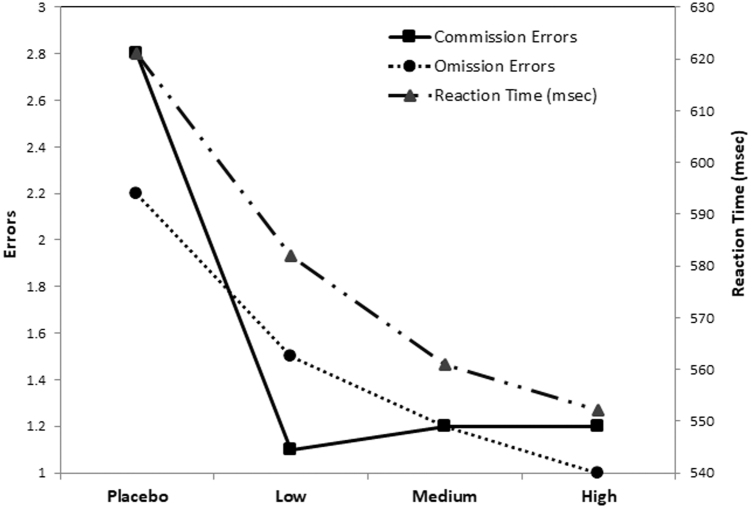

Sustained attention

Children with ASD/ADHD made significantly fewer omission errors, [F(3,69) = 7.21, p < 0.001], and commission errors [F(3,69) = 4.64, p = 0.005] on MPH, relative to placebo. They also responded more quickly at higher MPH doses, F(3,69) = 10.45, p < 0.001. Thus, the children were both faster and more accurate (fewer errors) at higher MPH doses—there was no speed/accuracy trade-off. As illustrated in Figure 2 and noted in Table 3, although performance continued to improve at successively higher MPH doses, the most dramatic improvements occurred between the placebo and low doses.

FIG. 2.

Performance on the continuous performance task as a function of methylphenidate dose.

Selective attention (visual and auditory)

Visual selective attention

On the SCT, children made fewer sorting errors on the SCT at higher doses F(3,69) = 4.22, p = 0.016. Although performance continued to improve at higher doses, the largest improvement was noted between the placebo and low doses, even though a smaller (but significant) improvement was noted between the medium and high doses.

Auditory selective listening

On the selective listening task, higher doses of MPH were associated with greater correct detection of auditory targets F(3,69) = 5.21, p = 0.003, fewer omissions, F(3,69) = 3.49, p = 0.03, and fewer random errors, F(3,69) = 2.94, p = 0.039. Interestingly, in this sample of children with autism, there were essentially no perseverative errors. Successive improvements were noted in correct detections throughout the entire dose range, with the medium and high doses showing the greatest gains relative to placebo. With regard to errors, overall, the greatest gains were noted between the placebo and low doses, with the exception of omissions, in which a significant reduction in these errors was noted between the low and medium doses.

Impulsivity/disinhibition

Delay of gratification

Higher MPH doses were associated with more correct responses, F(3,69) = 4.34, p = 0.007). Inspection of Table 3 indicates that the largest gain in correct responses occurred between the placebo and low MPH dose, with small incremental gains at higher MPH doses. There was no effect of MPH treatment on efficiency of responding, F(3,69) = 1.88, p = 0.158. Thus, higher doses of medication allowed our children to refrain from responding before the 4-second waiting interval—but it did not make them more efficient (in terms of no. of correct responses/total responses).

Matching Familiar Figures Test

Although the children made fewer errors at higher MPH doses, this effect did not quite reach statistical significance, F(3,54) = 2.33, p = 0.085, for this modest-size sample. There was no effect of MPH dose on reaction time, F(3,54) = 0.842, p = 0.477. Thus, on this very engaging task employing cartoon pictures, performance was not affected by MPH treatment.

Stop signal task

Children made more correct responses on “go” trials with higher doses of MPH, F(3,66) = 7.40, p < 0.001. The largest gains occurred between the placebo and low doses, although improvements continued to the high dose (relative to placebo). There was no effect of MPH dose on reaction time during “go” trials, F(3,66) = 2.28, p = 0.09. For “stop” trials, MPH did not affect accuracy F(3,66) = 1.65, p = 0.184. Although stop signal reaction time tended to be shorter at higher MPH doses, suggesting an improved ability to inhibit responding when instructed not to respond, this effect was not quite significant, F(3,66) = 2.36, p = 0.08. Interestingly, the stop signal delay increased significantly as a function of dose, F(3,66) = 3.38, p = 0.023. Given that the stop signal delay increases when children inhibit successfully and decreases when they fail to inhibit, inspection of Table 3 suggests that MPH helped to strengthen inhibition up to the medium dose. Although there was decline in the stop signal delay between the medium and high doses, this decline was not significant, t(22) = 1.46, p = 0.16. These findings suggest that the children were both more attentive with higher doses of MPH (they made more correct responses) and that they were better able to inhibit responding (as indicated by their ability to inhibit responding at longer delays between the initial signal and the stop signal).

Discussion

Our findings indicate that performance on cognitive tasks tapping sustained attention and selective attention improves with MPH treatment in children with ASD and ADHD, as well as some evidence of improvement in the ability to inhibit responding impulsively. Furthermore, these improvements were often linear in nature—that is, higher doses of MPH were usually associated with improvements in task performance. There were no significant curvilinear components to trend, suggesting that in the dose range studied in the investigation, higher doses did not result in deteriorating performance. Interestingly, on a number of the tasks, the largest gains were seen between the placebo and low MPH dose, with smaller increases (especially relative to placebo) seen in the medium and high doses. For the clinician, these findings suggest that cognitive performance might improve significantly at even low MPH doses, with titration upward from there depending upon perceived gains in learning and behavior—weighed against concerns with side effects.

These cognitive data are very consistent with the parent and teacher behavioral ratings obtained in the same trial (Pearson et al. 2013). However, this does not necessarily mean that the same doses were optimal for both behavior and cognition, as we have previously shown that changes in behavior and cognition often varied rather independently in the same children (Pearson et al. 2004a). Although group performance is associated with linear gains in both behavioral and cognitive responses, for any one child, increasing MPH doses may be associated with deterioration in functional status. Thus, as is the case for all children with ADHD, it is very important to monitor both behavioral and cognitive performances carefully in children with ASD+ADHD as medication is being titrated. Improvement in one does not necessarily imply that improvement will occur in the other. By extension, it is also important to note that although our overall group of children with ASD+ADHD demonstrated a favorable cognitive (and behavioral) response to MPH, any one child may improve or deteriorate in one (or both) of these domains.

Although cognitive tasks with demonstrated sensitivity to MPH treatment were used in this study, it is seldom feasible for clinicians to utilize these measures. Instead, it is usually more feasible to track cognitive performance using “real-world” rubrics such as report cards and even online grade tracking. Davis and Kollins (2012) have very appropriately noted the utility of going beyond laboratory tasks of cognition to obtain a broader scope of treatment response. In recent years, some school districts provide week-by-week grade (and behavior) information to parents about students. Although it was beyond the scope of this study to examine this important component of a child's functional abilities, future studies may incorporate such measures where they are available.

It is interesting that gender was not a moderator of treatment response, suggesting that boys and girls with ASD+ADHD responded to MPH in a similar manner. Combined with our previously reported findings of behavioral improvements with ER-MPH treatment in children with ASD+ADHD (Pearson et al. 2013), it appears that ER-MPH treatment is associated, on average, with both cognitive and behavioral improvements in elementary school-age boys and girls with ASD and significant symptoms of ADHD. However, it should be noted that our sample size was small (n = 24, including 5 girls), and that future studies with larger samples may be better poised to address the question of potential differences in MPH response in boys and girls with ASD+ADHD.

Although treatment with MPH was shown to be effective in our sample, pharmacotherapy should only be initiated and maintained as part of a comprehensive treatment plan for children with ASD and ADHD (Ji and Findling 2015; Antshel et al. 2016; Santosh and Singh 2016). Behavioral methods are an important part of this comprehensive treatment plan for children with ASD and ADHD, as are parent and teacher training. Given that MPH-related improvements in some aspects of social functioning were found in the RUPP study (e.g., social communication and self-regulation; Jahromi et al. 2009), it may be that MPH treatment may make children with ASD+AHD more receptive to social skills training—yet another component of a comprehensive intervention program. Thus, the MPH component of the child's comprehensive treatment regimen may provide a platform on which other new skills (e.g., aimed at behavioral and social modulation) can be very effectively built.

Future directions

Another aspect of MPH treatment response in ASD that is yet to be explored is the effect of stimulant treatment in adults with ASD who have significant symptoms of ADHD. A substantial percentage of children with ADHD in the general school-age population continue to have significant symptoms of ADHD (particularly inattention and impulsivity) as adults, even though symptoms of hyperactivity may abate with age (Pearson and Aman 1994; Sibley et al. 2012). Indeed, it may be the case that adults with ASD+ADHD may also continue to exhibit significant symptoms of ADHD that undermine their ability to function in jobs and in relationships. To our knowledge, there are no controlled trials of cognitive and behavioral response in adults with ASD+ADHD—this is clearly an area worthy of further investigation.

Yet another potentially fertile component of future studies of MPH response in ASD+ADHD might be the incorporation of genotyping of the participants, given that reduction in symptoms of hyperactivity with treatment in children with ASD was moderated by the genotypic profile (McCracken et al. 2014). In a similar vein, to our knowledge, there have been no controlled studies of MPH response in rare genetic illnesses that are associated with high risk of both ASD and ADHD such as the tuberous sclerosis complex (de Vries et al. 2018). As our understanding of the genetic underpinnings of developmental disabilities becomes more sophisticated, genetic signatures (e.g., TSC caused by the TSC1 gene versus the TSC2 gene) would prove to be a natural extension of this line of work. Future research may also track other biomarkers to monitor and understand which children with ASD are the best MPH responders. We concur with Ji and Findling (2015) and also with Antshel et al. (2016) that future studies with greater subject heterogeneity are very much needed.

It should also be noted that although this investigation employed measures of sustained attention, selective attention, and inhibition/impulsivity, many other cognitive domains remain to be studied in their response to MPH treatment in this population (e.g., divided attention, attention switching, memory, components of executive function such as organization and planning) in children—and adults—with ASD+ADHD. It will also be important for future studies to study the cognitive response to different stimulant medications.

Limitations

A limitation of this study was its rather short duration—that is, only 4 weeks of active medication. Although future studies aimed at longer periods of assessing MPH response would be helpful, it is important to note that previous investigations suggest that children who have a favorable response to MPH in the short term (up to 4 weeks) continued to respond well to MPH treatment regimens that lasted 2 months (RUPP 2005) or 3 months (Di Martino et al. 2004)—and 14 months in typically developing children with ADHD in the MTA (MTA Cooperative Group 1999). However, at very long intervals (e.g., of three or more years), the MTA and Preschool ADHD Treatment Studies have demonstrated that initial response to MPH may not predict longer term clinical effects (Jensen et al. 2007; Riddle et al. 2013). Thus, it will be important to explore the trajectory of MPH response over longer periods of time than was explored in this study in children with ASD+ADHD.

This study also examined the response to MPH in a relatively high-functioning group of children, so our findings may not be applicable to lower functioning children. It would be informative for future studies to explore MPH response in children with a wider range of ability level than was done in this trial (composed of higher functioning children with ASD), given that a more favorable MPH response has been found in children with ID and ADHD who were higher functioning (Aman et al. 1991a; Antshel et al. 2016)—although others (e.g., Stigler et al. 2004; Simonoff et al. 2013) have not found effects of intelligence quotient (IQ) on MPH response. Despite the limitation inherent in our higher functioning sample, results will likely be directly applicable to many patients with ASD and symptoms of ADHD, given that more and more high-functioning individuals with ASD—including adults with ASD—are being identified in recent years.

It is also interesting that our higher functioning sample (mean Full Scale IQ of 85) did not experience significant adverse events in the lead-in phase—unlike 6 of the 72 children in the RUPP study (mean IQ of 62.6), who experienced intolerable adverse events during the lead-in phase that led to them exiting the study. It is also interesting that 18% of the children in the RUPP study discontinued MPH treatment, and that irritability was the most common reason for study discontinuation. In our study, although irritability did not lead to study discontinuation, late afternoon irritability was the most common reason for discontinuing the afternoon IR-MPH dose. Clearly more research is warranted to determine if higher functioning children with ASD+ADHD experience less irritability during MPH treatment—or if it is manifested differently (e.g., in the late afternoon only), or if it is restricted mainly to immediate-release formulations.

As we noted in Pearson et al. (2013), our sample size was too small to examine the effects of moderators/mediators of response. However, we are aware of only a handful of randomized-controlled studies that have explored the effects of MPH treatment in children with ASD+ADHD that included more than 20 participants. We are also aware that the dose levels that we used in this study were conservative (by design), with our highest dose (0.48 mg/kg IR-MPH equivalent), which was similar to the highest MPH dose used in the RUPP study (0.50 mg/kg). Given that previous researchers (e.g., Sprague and Sleator 1977) found deteriorating cognitive performance at their highest MPH dose (1.0 mg/kg), we might have found cognitive declines at substantially higher doses. Thus, it remains to be seen in future investigations if there is a curvilinear cognitive response to MPH in children with ASD and ADHD at higher MPH doses (e.g., 1.0 mg/kg). Nevertheless, our more conservative doses appear to have resulted in significant improvements in behavior (Pearson et al. 2013), so the prescribing physician may not need to exceed them. In any event, both behavioral and cognitive gains should be weighed as MPH is titrated.

Conclusions

Many children with ASD+ADHD are routinely treated with stimulant medication to improve their problems with inattention and impulsivity, yet few well-controlled clinical trials have investigated the assumption that MPH is effective in improving cognitive problems. The current research addressed this issue in high-functioning elementary school-age children with ASD+ADHD. Results indicated that MPH—often in a very low dose—does improve cognitive performance on tasks tapping aspects of attention and impulse control that are critical to success in educational and social settings. Our overall body of work [this in conjunction with the parent and teacher ratings of favorable behavioral response in the same sample (Pearson et al. 2013)] indicates that psychostimulant treatment for some children with ASD+ADHD is effective in improving both behavioral and cognitive functions. Thus, MPH treatment in children with these dual diagnoses may help them attain educational and behavioral foundations to promote their developmental outcomes.

Clinical Significance

This study, in conjunction with our previous study (Pearson et al. 2013) suggests that children with ASD + ADHD show cognitive and behavioral improvements with stimulant medication treatment. These include improvements in sustained attention, selective attention, and impulsivity/inhibition; if realized in academic attainment, these improvements could enhance quality of life for such children. Ideally, clinicians should monitor behavioral and cognitive response to treatment, given that it is not possible to predict which children will benefit from treatment.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary versions of this article were presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in Toronto, Ontario, October 20, 2011, and to the International Meeting for Autism Research (IMFAR) in Toronto, Ontario, on May 18, 2012. The authors wish to express their appreciation to the children, parents, and teachers who participated in this study. They also wish to thank Ms. Ming (Brook) Lu, for her editorial assistance.

Disclosures

Dr. Pearson has received travel reimbursement and research support from Curemark LLC; research support from BioMarin and Novartis, and has served as a consultant to Curemark LLC. Dr. Santos and Ms. Mansour have received research support from Curemark LLC. Dr. Aman has received research contracts, consulted with, served on advisory boards, or done investigator training for Bracket Global; Cogstate Clinical Trials, Ltd.; J & J Pharmaceuticals; MedAvante-Prophase; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc., Ovid Therapeutics; Hoffmann-La Roche; Supernus Pharmaceuticals, and Zynerba Pharmaceuticals. He receives royalties from Slosson Educational Publications. Dr. Arnold has received research funding from Curemark, Lilly, Neuropharm, Shire, Roche/Genentech, Otsuka, and Young Living; has consulted to Organon, Pfizer, Shire, Sigma Tau, and Targacept; and has served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, BioMarin, Ironshore, Novartis, Noven, Shire, Tris Pharma, and Seaside Therapeutics. Dr. Casat has received research funding from Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Bukstein has served as a consultant to Ezra Innovations and PRIME CME; he has also received book royalties from the Routledge Press. Dr. Jerger has served as a consultant to Pearson Assessments/Psychological Corporation. The other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Aman MG: Stimulant drugs in the developmental disabilities revisited. J Dev Phys Disabil 8:347–365, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Kern RA, McGhee DE, Arnold LE: Fenfluramine and methylphenidate in children with mental retardation and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Laboratory effects. J Autism Dev Disord 23:491–506, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Lam KSL, Van Bourgondien ME: Medication patterns in patients with autism: Temporal, regional, and demographic influences. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 15:116–126, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Marks RE, Turbott SH, Wilsher CP, Merry SN: Clinical effects of methylphenidate and thioridazine in intellectually subaverage children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30:246–256, 1991a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Marks RE, Turbott SH, Wilsher CP, Merry SN: Methylphenidate and thioridazine in the treatment of intellectually subaverage children: Effects on cognitive-motor performance. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30:816–824, 1991b [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP): Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:894–921, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000

- Ames CS, White SJ: Brief report: Are ADHD traits dissociable from the autistic profile? Links between cognition and behaviour. J Autism Dev Disord 31:357–363, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amr M, Raddad D, El-Mehesh F, Bakr A, Sallam K, Amin T: Comorbid psychiatric disorders in Arab children with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectrum Disord 6:240–248, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Antshel KM, Zhang-James Y, Wagner KE, Ledesma A, Faraone SV: An update on the comorbidity of ADHD and ASD: A focus on clinical management. Expert Rev Neurother 16:279–293, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard AC, Ickowicz A, Logan GD, Hogg-Johnson S, Schachar R, Tannock R: Selective inhibition in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder off and on stimulant medication. J Abnorm Psychol 31:315–327, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Quintana H, Greenhill LL: Methylphenidate treatment of hyperactive autistic children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27:248–251, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M: Pharmacotherapy in early infantile autism. Biol Psychiatry 10:399–423, 1975 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M, Fish B, David R, Shapiro T, Collins P, Koh C: Response to tri-iodothyronine and dextroamphetamine: A study of preschool schizophrenic children. J Autism Child Schizophr 2:343–358, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Douglas VI, Morgenstern G: Cognitive styles in hyperactive children and the effect of methylphenidate. J Child Psychol Psychiat 12:55–67, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC: Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders among children aged 8 years: Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 63:1–22, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK: Conners Rating Scales–Revised. North Tonawanda, NY, Multi-Health Systems, Inc., 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Coury DK, Anagnostou E, Manning-Courtney P, Reynold A, Cole LK, McCoy R, Whitaker A, Perrin JW: Use of psychotropic medication in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 130:S69–S76, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard S, Nielsen HS, Simonsen M: Five-fold increase in national prevalence rates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and other psychiatric disorders: A Danish register-based study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 23:432–439, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis NO, Kollins SH: Treatment for co-occurring attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Neurotherapeutics 9:518–530, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries PJ, Wilde L, de Vries MC, Moavero R, Pearson DA, Curatolo P: A clinical update on Tuberous Sclerosis Complex-Associated Neuropsychiatric Disorders (TAND). Am J Med Genet C 178:309–320, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMartino A, Melis G, Cianchetti C, Zuddas A: Methylphenidate for pervasive developmental disorders: Safety and efficacy of acute single dose test and ongoing therapy: An open-pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 14:207–218, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Erkanli A, Conners CK, Klaric J, Costello JE, Angold A: Relations between continuous performance test performance measures and ADHD behaviors. J Abnorm Child Psychol 31:543–554, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen AJ, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Aman MG: A longitudinal investigation of psychotropic and non-psychotropic medication use among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 39:1339–1349, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier JA, Biederman J, Bellordre CA, Garfield SB, Geller DA, Coffey BJ, Faraone SV: Should the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder be considered in children with pervasive developmental disorder? J Atten Disord 4:203–211, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Shattuck PT, Narendorf SC, Cooper BP, Wagner M, Spitznagel EL: Prevalence and correlates of psychotropic medication use in adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder with and without caregiver-reported attention-deficit/disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 21:571–579, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan J, Cantwell DP: Dosage effects of methylphenidate on paired associate learning: Positive/negative placebo responders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 21:237–242, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Guttmacher LB, Bleeg M: Coexistence of childhood onset pervasive developmental disorder and attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity. Am J Psychiatry 138:388–389, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghuman JK, Aman MG, Lecavalier L, Riddle MA, Gelenberg A, Write R, Rice S, Ghuman HS, Fort C: Randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study of methylphenidate for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in preschoolers with developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19:329–339, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S, Schwebach AJ: The comorbidity of pervasive developmental disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Results of a retrospective chart review. J Autism Dev Disord 34:329–339, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M: The Gordon Diagnostic System. DeWitt, NY, Gordon Systems, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- Hall CW, Kataria S: Effects of two treatment techniques on delay and vigilance tasks with attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) children. J Psychol 126:17–25, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handen BL, Johnson CR, Lubetsky M: Efficacy of methylphenidate among children with autism and symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 30:245–255, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB: Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT, Department of Sociology, Yale University, 1975 [Google Scholar]

- Holm S: A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 6:65–70, 1979 [Google Scholar]

- Holttum JR, Lubetsky MJ, Eastman LE: Comprehensive management of trichotillomania in a young autistic girl: Case study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33:577–581, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino Y, Kumashiro H, Kaneko M, Takahashi Y: The effects of methylphenidate on early infantile Autism and its relation to serum serotonin levels. Folia Psychiatr Neurol Jpn 31:605–614, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia Y, Wong AYS, Murphy DGM, Simonoff E, Buitelaar JK, Wong ICK: Psychopharmacological prescriptions for people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A multinational study. Psychopharmacology 231:999–1009, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi LB, Kasari CL, McCracken JT, Lee L, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, Scahill L, Tierney E, Arnold LE, Vitiello B, Ritz L, Witwer A, Kustan E, Ghuman J, Posey DJ: Positive effects of methylphenidate on social communication and self-regulation in children with pervasive developmental disorders and hyperactivity. J Autism Dev Disord 39:395–404, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Arnold LE, Swanson J, Vitiello B, Abikoff HB, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hinshaw SP, Pelham WE, Wells KC, Conners CK, Elliott GR, Epstein J, Hoza B, Molina BSG, Newcorn JH, Severe JB, Wigal T, Gibbons RD, Hur K: Follow-up of the NIMH MTA study at 36 months after randomization. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:988–1001, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerger S: Validation of the pediatric speech intelligibility test in children with central nervous system lesions. Audiology 26:298–311, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji NY, Findling RL: An update on pharmacotherapy for autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Psychiatry 28:91–101, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Rosman B, Day D, Albert J, Phillips W: Information processing in the child: Significance of analytic and reflective attitudes. Psychol Monogr 78:Whole No. 578, 1964 [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Shonka S, French WP, Strickland J, Miller L, Stein MA: Dose response effects of long-activing liquid methylphenidate in children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A pilot study. J. Autism Dev Disord 47:2307–2313, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecavalier L: Behavioral and emotional problems in young people with pervasive developmental disorders: Relative prevalence, effects of subject characteristics, and empirical classification. J Autism Dev Disord 36:1101–1114, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecavalier L, McCracken CE, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, McCracken JT, Tierney E, Smith T, Johnson C, King B, Handen B, Swiezy NB, Arnold LE, Bearss K, Vitiello B, Scahill L: An exploration of concomitant psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorder. Compr Psychiatry 88:57–64, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DO, Ousley OY: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in a clinic sample of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16:737–746, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyfer OT, Folstein SE, Bacalman S, David NO, Dinh E, Morgan J, Tager-Flusberg H, Lainhart JE: Comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with autism: Interview development and rates of disorders. J Autism Dev Disorder 36:849–861, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipszyc J, Schachar R: Inhibitory control and psychopathology: A meta-analysis of studies using the stop signal task. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 16:1064–1076, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) Manual. Los Angeles, CA, Western Psychological Services, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Mansour R, Dovi AT, Lane DM, Loveland KA, Pearson DA: ADHD severity as it relates to comorbid psychiatric symptomatology in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Res Dev Disabil 60:52–64, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure FD, Gordon M: Performance of disturbed hyperactive and nonhyperactive children on an objective measure of hyperactivity. J Abnorm Child Psychol 12:561–571, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken JT, Badashova KK, Posey DJ, Aman MG, Scahill L, Tierney E, Arnold LE, Vitiello B, Whelan F, Chuang SZ, Davies M, Shah B, McDougle CJ, Nurmi EL: Positive effects of methylphenidate on hyperactivity are moderated by monoaminergic gene variants in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pharmacogenomics J 14:295–302, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mire SS, Nowell KP, Kubiszyn T, Goin-Kochel RP: Psychotropic medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders within the Simons Simplex Collection: Are core features of autism spectrum disorder related? Autism 18:933–942, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MTA Cooperative Group: A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: The MTA cooperative group multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:1073–1086, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickels KC, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voight RG, Barbaresi WJ: Stimulant medication treatment of target behaviors in children with autism: A population-based study. J Dev Behav Pediatr 29:75–81, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff S, Strayer DL: Inhibitory function in nonretarded children with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord 27:59–77, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock G, Amendah D, Ouyang L, Grosse S: Autism spectrum disorders and health care expenditures: The effects of co-occurring conditions. J Dev Behav Pediatr 33:2–8, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Aman MG: Ratings of hyperactivity and developmental indices. J Autism Dev Disord 24:395–411, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Aman MG, Arnold LE, Lane DM, Loveland KA, Santos CW, Casat CD, Mansour R, Jerger SW, Ezzell S, Factor P, Vanwoerden S, Ye E, Narain P, Cleveland LA: High concordance of parent and teacher ADHD ratings in medicated and unmedicated children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 22:284–291, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Lane DM, Santos CW, Casat CD, Jerger SW, Loveland KA, Mansour R, Henderson JA, Payne CD, Roache JD, Lachar D, Cleveland LA: Effects of methylphenidate treatment in children with mental retardation and ADHD: Individual variation in medication response. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43:686–698, 2004a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Lane DM, Swanson JM: Auditory attention switching in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol 19:477–490, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Loveland KA, Lachar D, Lane DM, Reddoch SL, Mansour R, Cleveland SL: A comparison of behavioral and emotional functioning in children and adolescents with autistic disorder and PDD-NOS. Child Neuropsychol 12:321–333, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Santos CW, Aman MG, Arnold LE, Casat CD, Mansour R, Lane DM, Loveland KA, Bukstein OG, Jerger SW, Factor P, Vanwoerden S, Perez E, Cleveland LA: Effects of extended release methylphenidate treatment on ratings of ADHD and associated behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders and ADHD symptoms. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 23:337–351, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Santos CW, Casat CD, Lane DM, Jerger SW, Roache JD, Loveland KA, Lachar D, Faria LP, Payne CD, Cleveland LA: Treatment effects of methylphenidate on cognitive functioning in children with mental retardation and ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43:677–685, 2004b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Yaffee LS, Loveland KA, Lewis KR: A comparison of sustained and selective attention in children who have mental retardation with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Ment Retard 100:592–607, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponde MP, Novaes CM, Losapio MF: Frequency of symptoms of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder in autistic children. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 68:103–106, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posey DJ, Aman MG, McCracken JT, Scahill L, Tierney E, Arnold LE, Vitiello B, Chuang SZ, Davies M, Ramadan Y, Witwer AN, Swiezy NB, Cronin P, Shah B, Carroll DH, Young C, Wheeler C, McDougle CJ: Positive effects of methylphenidate on inattention and hyperactivity in pervasive developmental disorders: An analysis of secondary measures. Biol Psychiatry 61:538–544, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle BA, Colpe LJ, Blumberg SJ, Avila RM, Kogan MD: Diagnostic history and treatment of school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder and special health care needs. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief, No. 97, May 2012. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db97.pdf (accessed July3, 2020) [PubMed]

- Prior M, Samson A, Freethy C, Geffen G: Auditory and attentional abilities in hyperactive children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 26:289–304, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana H, Birmaher B, Stedge D, Lennon S, Freed J, Bridge J, Greenhill L: Use of methylphenidate in the treatment of children with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 25:283–294, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapport MD, Kelly KL: Psychostimulant effects on learning and cognitive function. In: Handbook of Hyperactivity in Children. Edited by Matson JL. Needham Heights, MA, Allyn and Bacon, 1993, pp. 97–136 [Google Scholar]

- Realmuto GM, August GJ, Garfinkel BD: Clinical effect of buspirone in autistic children. J Clin Psychopharmacol 9:122–125, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich W, Welner Z, Herjanic B: Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents-IV. North Tonawanda, NY, Multi-Health Systems, Inc., 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Riccio CA, Waldrop JM, Reynolds CR, Lowe P: Effects of stimulants on the continuous performance test (CPT): Implications for CPT use and interpretation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 13:326–335, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roid GH: Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, 5th ed. Itasca, IL, Riverside Publishing, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Reiersen AM, Constantino JN, Volk HE, Todd RD: Autistic traits in a population-based ADHD twin sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 48:44–472, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network: Randomized, controlled, crossover trial of methylphenidate in pervasive developmental disorders with hyperactivity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:1266–1274, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle MA, Yershova K, Lazzaretto D, Pavkina N, Yenokyan G, Greenhill L, Abikoff H, Vitiello B, Wigal T, McCracken JT, Kollins SH, Murray DW, Wigal S, Kastelic E, McGough JJ, dosReis S, Bauzó-Rosario A, Stehli A, Posner K: The preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treatment study (PATS) 6-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:264–278, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosental RH, Allen TW: Intratask distractibility in hyperkinetic and nonhyperkinetic children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 8:175–187, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosvold HE, Mirsky AF, Sarason I, Bransome SD, Beck LH: A continuous performance test of brain damage. J Consult Clin Psychol 20:343–350, 1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Le Couteur A, Lord C: Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (WPS Edition). Los Angeles, CA, Western Psychological Services, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Santosh PJ, Baird G, Pityaratstian N, Tavare E, Gringas P: Impact of comorbid autism spectrum disorders on stimulant response in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A retrospective and prospective effectiveness study. Child Care Health Dev 32:575–583, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santosh PJ, Singh J: Drug treatment of autism spectrum disorder and its comorbidities in children and adolescents. BJPsych Adv 22:151–161, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Schachar RJ, Tannock R, Logan G: Inhibitory control, impulsiveness, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 13:721–739, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K: The effect of stimulant medication in childhood-onset pervasive developmental disorder—A case report. Dev Behav Pediatr 3:244–246, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BS, Gnagy EM, Waxmonsky JG, Waschbusch DA, Kuriyan AB: When diagnosing ADHD in young adults emphasize informant reports, DSM items, and impairment. J Consult Clin Psychol 80:1052–1061, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charmon T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G: Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47:921–929, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff E, Taylor E, Baird G, Bernard S, Chadwick O, Liang H: Randomized controlled double-blind trial of optimal dose methylphenidate in children and adolescents with severe attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and intellectual disability. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 54:527–535, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinzig J, Walter D, Doepfner M: Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Symptom or syndrome? J Atten Disord 13:117–126, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn A, Pinsker H: Use of stimulant medication in treating pervasive developmental disorder. Am J Psychiatry 138:997, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague RL, Sleator EK: Methylphenidate in hyperkinetic children: Differences in dose effects in learning in social behavior. Science 198:1274–1276, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stigler KA, Desmond LA, Posey DJ, Wiegand RE, McDougle CJ: A naturalistic retrospective analysis of psychostimulants in pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 14:49–56, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayhorn JM, Rapp N, Donina W, Strain PS: Randomized trial of methylphenidate for an autistic child. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27:244–247, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt GF, Anderson DR, Well AD: A developmental study of the effects of irrelevant information on speeded classification. J Exp Child Psychol 20:127–135, 1975 [Google Scholar]

- Sturm H, Fernell E, Gillberg C: Autism spectrum disorders in children with normal intellectual levels: Associated impairments and subgroups. Dev Med Child Neurol 46:444–447, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes DH, Douglas VI, Weiss G, Minde KK: Attention in hyperactive children and the effect of methylphenidate (Ritalin). J Child Psychol Psychiatry 12:129–139, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen F, Aron AR, Band G, Beste G, Bissett PG, Brockett AT, Brown JW, Chamberlain SR, Chambers CD, Colonius H, Colzato LS, Corneil BD, Coxon JP, Dupuis A, Eagle DM, Garavan H, Greenhouse I, Heathcote A, Huster RJ, Jahfari SJ, Kenemans JL, Leunissen I, Li C, Logan GD, Matzke D, Morein-Zamir S, Murthy A, Pare M, Poldrack RA, Ridderinkhof KP, Robbins TW, Roesch M, Rubia K, Schachar RJ, Schall JD, Stock AK, Swann NC, Thakkar KN, van der Molen MW, Vermeylen L, Vink M, Wessel JR, Whelan R, Zandbelt BB, Boehler CN: A consensus guide to capturing the ability to inhibit actions and impulsive behaviors in the stop-signal task. eLife 8:e46323, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitriol C, Farber B: Stimulant medication in certain childhood disorders. Am J Psychiatry 138:11, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar FR, Hoder EL, Cohen DJ: Inappropriate uses of stimulant medications. Clin Pediatr 24:127–130, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenarr WA: Note on the construction of digram-balanced Latin Squares. Psychol Bull 72:384–386, 1969 [Google Scholar]

- Winer BH, Brown DR, Michel KM: Statistical Principles in Experimental Design. NY, McGra w-Hill, 1971 [Google Scholar]

- Witwer A, Lecavalier L: Treatment incidence and patterns in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 15:671–681, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]