Abstract

Introduction

– Early detection plays a major role to reduce the mortality of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Many adjunctive techniques have emerged with claims of differentiating high risk oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) from benign lesions. Toluidine blue (TB) test has been established as a diagnostic adjunct in detecting high risk OPMDs and early asymptomatic OSCCs. As majority of OSCC are preceded by OPMDs, recognition of them at an early stage is important in the management of this devastating disease.

Methods

–This study was conducted as a multi-center study prospectively for a period of 2 years. Sixty five patients presented with OPMDs were selected and TB test was performed followed by a biopsy for histopathological confirmation. Criterion validity was assessed with histological diagnosis of the incisional biopsy of the OPMD as a gold standard test verses TB test results.

Results

The sensitivity of the TB test was 68.3% and the specificity 63.1% with a false positive rate of 36.8% and false negative rate of 31.7%. However, the predictive value of the positive test was 80%.

Conclusion

– TB testing might be a potential adjunct diagnostic aid in identifying high risk OPMDs. Further studies with extensive sample size and different demographics are needed to validate our findings.

Keywords: Diagnostic aid, OPMD, OSCC, Prospective, Toluidine blue, Tool, Validation

1. Introduction

The traditional definition of Oral cancer can be considered as oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) of the lip, oral cavity and oropharynx, as OSCC composes majority of the oral neoplasms that develops in the oral cavity.1 OSCC represents 4% of the malignancies in the developed countries, while in Southeast Asian region it rises up to 40%.2 OSCC can be preceded by oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) which are clinically evident as leukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucous fibrosis (OSF), oral lichen planus (OLP), discoid lupus erythematosis (DLE) or actinic cheilitis in the oral mucosa and lip. Histological evaluation of those lesions would reveal varying degrees of cytological and architectural abnormalities which are collectively called “dysplasia” or “atypia”.3

Despite numerous advances in treatment of OSCC, the 5-year survival has remained approximately 50% for the last 50 years.4 This poor prognosis is likely due to the advanced extent of the disease at the time of diagnosis, with over 60–70% of patients presenting at stages III and IV.1

The incidence rate of cancer of the oral cavity and oro-pharynx in Sri Lanka, excluding salivary neoplasms, standardized to the world standard population in the year 2018 was 12.3 and 3.6 per 100,000 populations, in males and females respectively.5 However, according to data presented in GLOBACAN 2018, the incidence of OSCC in Sri Lanka is 2152 and the deaths associated with the disease is 1077 and National Cancer Registry in 2012, reports 11.6% of all reported cancers are oral cancer and carrying highest mortality rate among different types of cancers (3 deaths per day).2,5,6

An approach to this problem is to improve the ability of oral health care professionals to detect relevant OPMDs at their earliest or most incipient stages. This can be achieved by secondary prevention which involves increasing public awareness about the relevance of regular oral screening or case finding examinations to identify small, otherwise asymptomatic OPMDs. Another strategy that will help the dental specialist to assess persistent oral lesions of uncertain biologic significance is the development and use of diagnostic aids.1,7,8 Furthermore, there is a strong need to follow an inter-professional collaborative approach, designed by the field experts, to improve the early diagnosis and systemic health of the patient.9

Many adjunctive techniques are in practice which claims enhancement of oral mucosal examinations by facilitating the detection of distinctions between benign, potentially malignant and malignant lesions oral lesions.8,10

Toluidine blue (TB), an acidophilic metachromatic dye of thiazine group selectively stains acidic tissue components (sulfates, carboxylates and phosphate radicals), thus staining DNA and RNA.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 TB test has been established as a diagnostic adjunct in detecting oral lesions related to invasive carcinomas, carcinoma in situ or early asymptomatic oral carcinomas.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 1% TB solution (B-CHEMS, Chennai) is composed of tolonium chloride-1 gram, acetic acid-10 ml, absolute alcohol-4.19 ml and distilled water-86 ml. TB stains tissues based on the principle of metachromasia. TB dye is attracted to polyanions by Van der Waals bonds, and there by bind to DNA or RNA as does hydrophobic bonding.23 TB solution is applied with the help of cotton swab and retention of stain in ‘blue’ colour is considered as positive for the test.

Use of TB test as a diagnostic aid for OPMD and OSCC has been widely reported in the literature with varying degree of sensitivity and specificity for the detection. In a study conducted in India has shown a sensitivity of 86.36% and specificity of 76.9%.24

The reliability of TB testis questionable in detecting OPMDs which present as erosive or ulcerated lesions, as it could give rise to false positive results due to false retention of stain in ulcerated and inflamed areas of the lesion.23 TB test had been proven to be effective in detecting satellite lesions (field cancerization).25

National guideline for screening, surveillance, diagnosis and management of OPMD was introduced in 2013 in Sri Lanka and role of each category of staff is clearly stated.26 According to the guideline, mandate was given to the dental surgeons at the primary dental clinic to manage the patient with leukoplakia (group B-low risk group) and early sub mucous fibrosis at the primary dental clinic without referring to the OMF units for diagnosis and further investigation. However, literature has been revealed that innocent looking lesions also may show some degree of dysplasia therefore, to minimise the chances of misdiagnosing these innocent looking lesions at an early stage, it has been decided to introduce TB test to select the cases requiring further investigations.27 Further, introduction of this test at primary dental care units will enhance the compliance of the patients as well.

Therefore the main objective of this multi-centre prospective study was to validate TB test as a diagnostic tool in order to detect dysplasia or high risk area within OPMDs.

2. Methodology

This study was designed as a multi-centre descriptive validation study and was conducted at the Faculty of Dental Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka (Department of Oral Medicine and Periodontology), Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila, Sri Lanka (Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Unit) and Institute of Oral Health, Maharagama, Sri Lanka from January 1, 2018 to January 1, 2020. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee, Faculty of Dental sciences. University of Preadeniya, Sri Lanka.

Patients who were above 18 years of age, with a clinical diagnosis of leukpoplakia, erythroplakia, OSF, DLE or OLP (OPMDs) were recruited for the study. Informed consent was obtained and all consented patients were investigated by a standard protocol that involved clinical examination followed by TB application and visualization. Staining was photographed followed by a biopsy for histopathological investigations. All study subjects were managed according to the OPMD guideline developed by the National Cancer Control Programme, Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka.25

Patients with medical complications (Ex-uncontrolled diabetes), lesions in the back of the mouth where application of the dye is difficult, biopsy is difficult under local anaesthesia, patients with previous history of OSCC, patients with mouth opening less than 15 mm and patients with asymptomatic reticular type of oral lichen planus were excluded from the study.

An interviewer administered pre-tested questionnaire was used in Sinhala, English and Tamil languages to acquire personal data, history of the complaint, medical and drug history as well as habit history.

Dental surgeons in the selected institutions were trained by the expert in the field of Oral Medicine at their institutions. Live demonstrations of TB application were carried out to familiarise the procedure during the training programme. Comprehensive clinical examination was conducted under good light source and the clinical diagnosis was established by these trained dental surgeons under the guidance of specialists. All mucosal changes and the clinical appearance, location, size of each lesion were recorded using a standard form. The main site of morphologically altered mucosa was selected and photographed. 1%TB is applied in 4 steps; first, rinsing of oral cavity with water for 20 s to remove debris, then application or rinse with 1% acetic acid for 20 s, after that application or rinse with TB solution (1% W/W) for 20 s and finally application or rinse with 1% acetic acid for 20 s to eliminate mechanically retained stains.

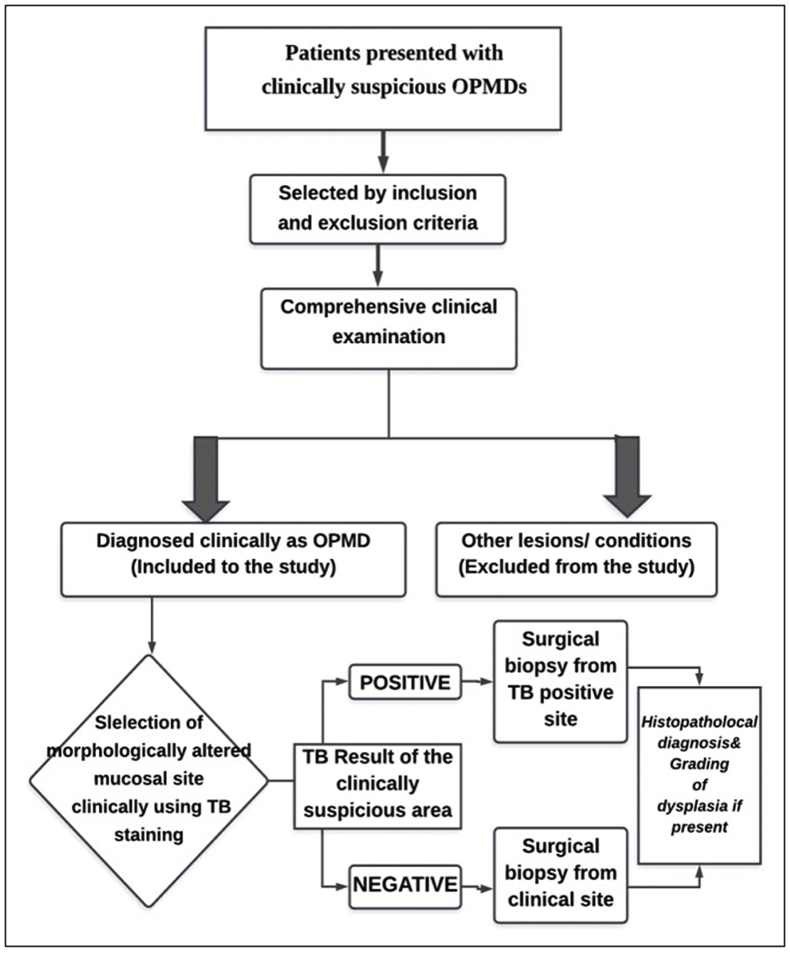

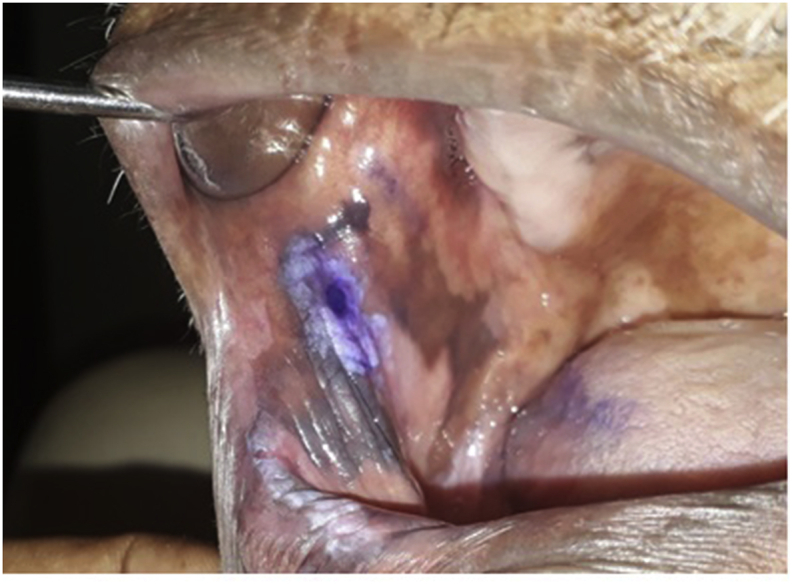

A royal blue or a navy blue stain as shown in Fig. 1 was considered as a positive result even if either the entire lesion or a portion of the lesion is stained or stippled. A light blue staining is considered doubtful. If there is no colour absorbed by the lesion, it was taken as a negative stain. A surgical incisional biopsy was performed from all subjects for histopathological diagnosis and cases with positive TB test; the biopsy was performed from positive region under local aesthesia. Patients were managed with the standard management protocol (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

A representative TB strain indicting a dark blue staining area which considered as positive.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the standard management protocol.

Histopathological diagnosis was done according to WHO 2017 as mild moderate and severe epithelial dysplasia.28

Criterion validity in terms of sensitivity, specificity, false positive rate, false negative rate, predictive value of the positive and negative test results, were assessed with histological diagnosis of the incisional biopsy of the OPMD as a gold standard test verses TB test results.

3. Results

Sixty five OPMD/oral cancer patients were recruited for the study and TB test was carried out among them (Table 1). Sixteen patients with leukoplakia gave positive TB test out of 26 patients. There were 17 OSF patients out of which 7 expressed blue staining for TB test. However, data regarding histopathological diagnosis was available only on 60 patients (Table 2). Out of all lesions, 5 cases confirmed as OSCC and 80% of them expressed positivity for TB test. 83.3% of severe epithelial dysplasia cases were positive for TB test and a case with carcinoma in situ was also positive. Interestingly, 66.7% of no or mild epithelial dysplasia (low risk) cases were negative for TB test. This indicated that the biopsy site was accurately demonstrated by TB with gradual increase of positivity when dysplasia grading ranged from mild towards worst.

Table 1.

Relationship between clinical characteristics of oral lesions and the TB test results.

| Clinical finding | Toluidine blue |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | + | – | |

| Leukoplakia | 26 | 16 (61-5%) | 10 (38.5%) |

| Oral Lichen Planus | 7 | 4 (57.1%) | 3 (42.9%) |

| Chronic Hyperplastic Candidiasis | 1 | 0 | 1 (100%) |

| OSMF | 17 | 7 (41.2%) | 10 (58.8%) |

| Erythroplakia | 4 | 4 (100%) | 0 |

| Malignant ulcer | 8 | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Verrucous carcinoma | 1 | 1 (100%) | 0 |

| Fibro epithelial hyperplasia |

1 |

1 (100%) |

0 |

| Total | 65 | 38 | 27 |

Table 2.

Histopathological findings of oral lesions and the concordance of the toluidine blue results.

| Histopathological finding | Toluidine blue |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | + | – | |

| No dysplasia | 19 | 7 (36.8%) | 12 (63.2%) |

| Mild epithelial dysplasia | 9 | 3 (33.3%) | 6 (66.7%) |

| Moderate epithelial dysplasia | 20 | 15 (75%) | 5 (25%) |

| Severe epithelial dysplasia | 6 | 5 (83.3%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Carcinoma in situ | 1 | 1 (100%) | 0 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

5 |

4 (80%) |

1 (20%) |

| Total | 60 | 35 | 25 |

Table 3 shows the relationship between TB test results and histological diagnosis (presence or absence of dysplasia).Histopathological diagnosis was taken in to consideration when the criterion validity of the TB test was assessed.

Table 3.

Relationship between TB test results and histological diagnosis.

| Test | Dysplasia N (%) | No Dysplasia N (%) | Total N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TB test positive | 28 (46.6) | 7 (11.7) | 35 (58.3) |

| TB test Negative | 13 (21.6) | 12 (20) | 25 (41.7) |

| Total | 41 (68) | 19 (32) | 60 (100) |

The sensitivity of the TB test was 68.3% and the specificity 63.1% with a false positive rate of 36.8% and false negative rate of 31.7%. However, the predictive value of the positive test was 80% and the predictive value of the negative test was 48%.

4. Discussion

Clinical diagnosis of OPMD and OSCC at its early stage is a challenge. Early lesions of OSCC often are asymptomatic and can mimic other conditions29 and some of them may not be readily visible on routine clinical examination. Differentiation between malignant and benign lesions in the oral cavity could be difficult even for an experienced clinician with clinical examination alone. Even though visual clinical examination is considered the simplest and currently most satisfactory method in screening of OSCC, cases can be missed. Further, justifying a surgical biopsy may not be easy for some patients with the clinical features alone at their early stages. Thus on the other hand malignant transformation can happen even with an innocent looking early lesion. The experience of the clinician can have a significant impact on the proper diagnosis of OMPD and OSCC. Thus, adjunct screening aids have been developed with varying levels of sensitivity and specificity to assist clinicians in order to detect high risk lesions.30 These include vital tissue staining (Toluidine Blue, Rose Bengal dye), cytology, light-based detection systems,31,32 narrow-emission tissue fluorescence (VELscope),33 chemiluminescence (Vizilite)34 and salivary biomarkers. They differ in their sensitivity and specificity and cannot be used routinely as many are expensive and none have achieved clinical utility. In a systematic review conducted by Giovannacci et al., in 201635 on non-invasive diagnostic tools, they identified an inconsistency in reported values and also found that no tool was identified to be superior over the other. They suggested the need of clinical trials to assess the real usefulness of these diagnostic tools.

Toluidine blue is an acidophilic metachromatic dye of the thiazine group, selectively stains acidic tissue components, visualising nucleic acids. TB test has been established as a diagnostic adjunct in detecting oral lesions related to invasive carcinomas, carcinoma in situ or early asymptomatic oral carcinomas. Retention of stain after an acetic acid rinse is considered as a positive test result. There are false positives from ulcerated and inflammatory lesions. Nevertheless, TB test as a diagnostic aid for OPMD and oral cancers has been widely reported in the literature with varying degrees of sensitivity and specificity.36,37 TB test has been reported to be superior in identifying oral cancer.38 It is not a diagnostic test for the detection of oral cancer but is a useful screening tool. TB test is effective as an adjunct diagnostic tool for use in the high-risk populations.39

The sensitivity of the TB test was 68.3% and the specificity 63.1% with a false positive rate of 36.8% and false negative rate of 31.7%. However, the predictive value of the positive test was 80% and the predictive value of the negative test was 48%.

There are different values reported in the literature. In some studies, they have identified an increased value than our study,40 whereas some had values closer to ours and in some, values were decreased than our findings. In a meta-analysis, Macey et al. (2015)30 have reported a sensitivity of the TB test to be 0.84 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.90) and a specificity of 0.70 (0.59–0.79). Parakh et al. (2017)40 reported that sensitivity of TB test was 88.89%, and specificity 74.19%. Positive predictive and negative predictive values were 50% and 97.83%, respectively in their study. Upadhyay et al. (2011)41 has reported worst values than in the present study where sensitivity was reported as 73.9% and specificity as 30%. The positive predictive value in them was 54.8% and negative predictive value of 50%. They have noted that false negative result in their study was mainly attributed to mild dysplasia whereas the false positive results included hyperkeratosis, hyperplasia, lichen planus and traumatic ulcer. With their findings they have concluded that TB staining should not blindly direct the opinion. They strongly recommended to discourage the use of TB test as a screening test.41 It has not been identified as a site specific tool but as a screening tool for the mouth as a whole.39 Another study revealed the sensitivity and specificity values for TB test in detecting malignant or dysplastic lesions to be 65.5% and 73.3%, respectively. Their positive predictive value was lower at 35.2% whereas negative predictive value was higher than ours (90.6%).14

The present study composed with different types of OPMDs and was interesting to note that most of the false positivity and negativities were observed in the cases with no or mild epithelial dysplasia whereas with high grade dysplasia and oral cancer, TB test become more accurate. It is important to identify the high risk lesions from the management point of view hence TB test can be considered as an important adjunct tool.

With our results and results from some other studies14 use of TB test as a diagnostic aid can be recommended but not as the one and only screening test but to couple with other screening aids. It is a simple procedure with very low cost.42 Considering the difficulties in conducting the other tests and the cost involved; we believe that TB test still has a role to play in screening OPMD and OSCC especially the high risk groups in countries with low income and resources.

One of the difficulties in interpreting the results of the TB stain is the subjectivity. Proper training sessions are necessary to overcome the issue. It is easy to recognize the negative cases and strongly positive cases whereas the difficulty is with intermediate/faintly positive cases. Development of a colour guide to identify the positive cases may improve the sensitivity and specificity of the test. Most significant limitation of this study is the limited number of cases. In addition, lack of control group is limiting the comparison of accuracy.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

Per our findings, TB might be a potential adjunct diagnostic aid in identifying high risk OPMDs however, requires further studies with extensive sample size and different demographics to validate our findings.

References

- 1.Lingen Mark W., Kalmar John R., Theodore Karrison, Speight Paul M. Critical evaluation of diagnostic aids for the detection of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Padmakumary G., Varghese C. 1997. Hospital cancer Registry. Thiruvananthapuram: Regional cancer centre; 2000; pp. 3–7. Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajendran R. sixth ed. Elsevier; Noida: 2009. Shafer's Textbook of Oral Pathology; pp. 80–218. Section 1 (Chapter 2) Benign and Malignant tumors of the Oral Cavity. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignon J.P., le Maître A., Maillard E., Bourhis J. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomisedtrials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Global Health Observatory . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2018. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/144-sri-lanka-fact-sheets.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Control Programme MoH, Nutrition & Indigeneous Medicine . Colombo: NCCP 14th Publication National Cancer Control Programme; 2020. Sri Lanka - 2012,. Cancer Incidence Data: Sri Lanka year 2012. Narahenpita, Colombo 5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouquot J.E., Suarez P., Vigneswaran N. Oral precancer and early cancer detection in the dental office – review of new technologies. J. Implant Adv Clin Dent. 2010;2:47–63. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefano Fedele Diagnostic aids in the screening of oral cancer. Head Neck Oncol. 2009:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao N.R., Villa A., More C.B. Oral submucous fibrosis: a contemporary narrative review with a proposed inter-professional approach for an early diagnosis and clinical management. J Otolaryngol - Head & Neck Surg. 2020;49 doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-0399-7. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scully C., Bagan J.V., Hopper c, Epstein J.B. Oral cancer: current and future diagnostic techniques. Am J Dent. 2008;21:199–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shedd D.P., Hukill P.B., Bahn S. Further appraisal of in vivo staining properties of oral cancer. Arch Surg. 1967;95:16–22. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1967.01330130018004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myers Eugene N. The toluidine blue test in lesions of the oral cavity. CA - Cancer J Clin. 1970;20 doi: 10.3322/canjclin.20.3.134. 134–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vahidy N.A., Zaidi S.H.M., Jafarey N.A. Toluidine blue test for detection of carcinoma of the oral cavity: an evaluation. J Surg Oncol. 1972:434–438. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930040505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paloma Cancela-Rodríguez, Rocío Cerero-Lapiedra, Germán Esparza-Gómez, Silvia Llamas-Martínez, WarnakulasuriyaSaman The use of toluidine blue in the detection of pre-malignant and malignant oral lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;40:300–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ather Siddiqui Imtiaz, Umer Farooq M., Ahmed Siddiqui Riaz, Rafi SM Tariq. Role of toluidine blue in early detection of oral cancer. Pak J Med Sci. 2006;22:184–187. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein J.B., Silverman S., Jr., Epstein J.D., Lonky S.A., Bride M.A. Analysis of oral lesion biopsies identified and evaluated by visual examination, chemiluminescence and toluidine blue. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allegra E., Lombardo N., Puzzo1 L., Garozzo A. The usefulness of toluidine staining as a diagnostic tool for precancerous and cancerous oropharyngeal and oral cavity lesions. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2009;29:187–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Lewei, Williams Michele, Poh Catherine F. Toluidine blue staining identifies high-risk primary oral premalignant lesions with poor outcome. Canc Res. 2005;65:8017–8021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma Navneet. Mubeen Non -invasive diagnostic tools in early detection of oral epithelial dysplasia. J Clin Exp Den. 2011;3:184–188. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portugal L.G., Wilson K.M., Biddinger P.W., Gluckman J.L. The role of toluidine blue in assessing margin status after resection of squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:517–519. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890170051010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strong M.S., Vaughan C.W., Incze J.S. Toluidine blue in the management of carcinoma of the oral cavity. Arch Otolaryngol. 1968;87:101–105. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1968.00760060529017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herlin P., Marnay J., Jacob J.H., Ollivier J.M., Mandard A.M. A study of the mechanism of the toluidine blue dye test. Endoscopy. 1983;15:4–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar G.L., Kiernan J.A. second ed. Dako North America; California: 2010. Education Guide: Special Stains and H & E. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vashisht Neha, Ravikiran A., Samatha V. Chemiluminescence and toluidine blue as diagnostic tools for detecting early stages of oral cancer: an invivoStudyJ. Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(4):ZC35–ZC38. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7746.4259. Apr. Published online Apr 15, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epstein J.B., Oakley C., Millner A., Emerton S., van der Meij E. The utility of toluidine blue as a diagnostic aid in patients previously treated for upper oropharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:537–547. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Cancer Control Programme MoHSL Guideline for the screening, surveillance,diagnosis and management of oral potentially malignant disorders- second edition. 2017. https://www.nccp.health.gov.lk/index.php/publications/guidelines Accessed on 10th October 2019.

- 27.Reibel J. Prognosis of oral pre-malignant lesions: significance of clinical, histopathological, and molecular biological characteristics. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14(1):47–62. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Naggar A.K., Chan J.K., Grandis J.R., Takata T., Slootweg P.J. fourth ed. vol. 9. WHO/IARC Classification of Tumours; 2017. International agency for research on cancer (IARC) press. (WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bagan J.V., Bagan-Debon L. Clinical presentation and differential diagnosis of oral cancer. In: Warnakulasuriya S., Greenspan J., editors. Text Book of Oral Cancer. Springer; Berlin: 2020. pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macey R., Walsh T., Brocklehurst P. Diagnostic tests for oral cancer and potentially malignant disorders in patients presenting with clinically evident lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(5) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010276.pub2. May 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiwari L., Kujan O., Farah C.S. Optical fluorescence imaging in oral cancer and potentially malignant disorders: a systematic review. Oral Dis. 2020;26(3):491–510. doi: 10.1111/odi.13071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rashid A., Warnakulasuriya S. The use of light-based (optical) detection systems as adjuncts in the detection of oral cancer and oral potentially malignant disorders: a systematic review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;44(5):307–328. doi: 10.1111/jop.12218. May. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagi R., Reddy-Kantharaj Y.B., Rakesh N., Janardhan-Reddy S., Sahu S. Efficacy of light based detection systems for early detection of oral cancer and oral potentially malignant disorders: systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2016;21(4):e447–e455. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21104. Published 2016 Jul 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ram S., Siar C.H. Chemiluminescence as a diagnostic aid in the detection of oral cancer and potentially malignant epithelial lesions. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34(5):521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giovannacci I., Vescovi P., Manfredi M., Meleti M. Non-invasive visual tools for diagnosis of oral cancer and dysplasia: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2016;21(3) doi: 10.4317/medoral.20996. e305‐e315. Published 2016 May 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warnakulasuriya K.A., Johnson N.W. Sensitivity and specificity of OraScan (R) toluidine blue mouthrinse in the detection of oral cancer and precancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Awan K.H., Morgan P.R., Warnakulasuriya S. Assessing the accuracy of autofluorescence, chemiluminescence and toluidine blue as diagnostic tools for oral potentially malignant disorders—a clinicopathological evaluation. Clin Oral Invest. 2015;19(9):2267–2272. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chhabra N., Chhabra S., Sapra N. Diagnostic modalities for squamous cell carcinoma:an extensive review of literature-considering toluidine blue as a useful adjunct. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2015;14(2):188–200. doi: 10.1007/s12663-014-0660-6. (Apr–June. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patton L.L., Epstein J.B., Kerr A.R. Adjunctive techniques for oral cancer examination and lesion diagnosis: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(7):896–994. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parakh M.K., Jagat Reddy R.C., Subramani P. Toluidine blue staining in identification of a biopsy site in potentially malignant lesions: a case–control study. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2017;4:356–360. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_38_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Upadhyay J., Rao N.N., Upadhyay R.B., Agarwal P. Reliability of toluidine blue vital staining in detection of potentially malignant oral lesions - time to reconsider. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2011;12:1757–1760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lingen M.W., Kalmar J.R., Karrison T., Speight P.M. Critical evaluation of diagnostic aids for the detection of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(1):10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]