Abstract

Background

As the coronavirus 2019 pandemic continues, healthcare services need to adapt to continue providing optimal and safe services for patients. We detail our adaptive framework as a large Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics service in a tertiary academic institution in Singapore.

Methods

The multidisciplinary team at our unit implemented various adaptations and workflow processes during this evolving pandemic in providing continued clinical care tailored to the challenges specific to our patient population. Services were continued via teleconsultation mode during the ‘Circuit Breaker’ (enhanced movement restriction) period. Specific workflow processes, IT infrastructure, and staff training were put in place to support smooth running of this service. Segregation of services into two teams based at two separate sites and implementation of stringent infection control measures surrounding the clinic visit by providers, patients and their families were incorporated to ensure safety. Measures were also taken to ensure providers' mental wellbeing.

Results

The clinical service was continued for the majority of our patients with a lowest reduction in patient consultations to half of baseline during the ‘Circuit Breaker’ period. We received positive feedback from families for teleconsultation services provided.

Conclusion

We have been able to continue services in our DBP clinics due to our dynamic reassessment of workflow processes and their prompt implementation in conjunction with the hospital and national public health response to the pandemic. Given that this pandemic is likely to be long drawn, our unit remains ready to constantly adjust these workflows and make adaptations as we go along, together with the support for mental health of patients, parents and staff. Continual improvements in workflows will be helpful even beyond the pandemic to ensure good continuity of care for our patients and families.

Key Words: child development, COVID-19, DBP, developmental delays, service development

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic on 12 March 2020.1 Singapore reported its first case of COVID-19 on 23 January 2020. By February 2020, Singapore had one of the highest numbers of COVID-19 cases out of China prior to the rapid spread of the disease in South Korea, Europe, USA and the rest of the world.2 Across countries, measures were initiated to ensure staff and patient safety, enhance infection control and ensure operational continuity in healthcare. In Singapore, with increasing community spread of COVID-19, the government tightened measures with a ‘Circuit Breaker’ (CB) from 3 April 20203 to 1 June 2020, where all ‘non-essential’ services were asked to cease operations and movement of people was curtailed apart from that for essential purposes. Schools were closed and students received Home-Based Learning (HBL) virtually. Non-acute health services including Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics (DBP) service were required to suspend clinic visits, whenever possible.

There have been numerous reports on adaptation of clinical services to the pandemic,4 , 5 but there is limited information specific to a DBP service in Singapore or elsewhere. This paper aims to illustrate the adaptation of a DBP service in a national center in Singapore and provide an example of how DBP services can be safely and efficiently continued during this pandemic.

1.1. Unique features of a DBP service

The primary role for healthcare organizations in a pandemic is to tend to their patients while ensuring safety of both patients and staff.6 There are certain features that are unique to DBP practice that would influence how these aims are prioritized and implemented.

Firstly, early recognition of developmental delay in young children is crucial.7 , 8 Risk of missing the window of opportunity to intervene - particularly during a pandemic, where resources are scarce9 - is real. Moreover, the DBP practice relies primarily on close observations and direct interactions with the children.10 This poses a challenge when telemedicine does not allow physicians to engage a child directly.11

Secondly, the mainstay of treatment of DBP conditions is behavioral therapy. Time-sensitive periods of therapy intervention and stimulation are of essence in very young children, as we know from the neurobiology of early neuronal development and growth.12 With closure of therapy and early intervention centers during prolonged lockdown, DBP patients lose treatment opportunities and risk regression of skills. Medications can be delivered to patients’ homes; however, it is more challenging to deliver therapy over a telemedicine platform.13 The developmental costs and consequences from delayed diagnoses and interventions for patients may only be realized in years to come.14 , 15

Thirdly, DBP service provides support for the mental and emotional health of patients and their caregivers. Caregivers of children with developmental needs experience immense stress at baseline.16 Living in enclosed quarters with disruption to their daily routine is most likely to exacerbate this stress.

It is known that there is increased domestic violence and abuse in families of children with disabilities.17 , 18 There have been reports of behavioral disorders in children due to the COVID-19 pandemic19 further exacerbating the caregiver stress and risk of victimization.

Lastly, the DBP patient population has unique characteristics that render them more susceptible to community-acquired infections. Children with cognitive impairments may be unable to follow public health recommendations, such as hand hygiene measures, wearing masks and physical distancing. These, coupled with prolonged contact time between provider and the patient during consultations, pose an increased infection risk for patients and providers.

It is imperative that there is continuity of care for patients in DBP services, while minimizing the risk of transmission of COVID-19. Continued DBP services would avert extending an already long DBP waitlist20 in most clinics and thus benefit future patients too. As a large DBP service in Singapore, we underwent multiple organizational changes in order to continue our DBP services.

1.2. Features of our DBP service

The Child Development Unit (CDU) at National University Hospital, Singapore is part of a tertiary academic institution. It is one of the two nationally designated organizations for DBP that provides subsidized care for preschool children with a range of learning, behavioral and developmental difficulties. Both institutions function along the same model of care.21 We are based at 3 separate sites across the western part of Singapore. We have a multidisciplinary team consisting of about 50 professionals: Developmental Pediatricians, Allied Health Professionals (AHP), Psychologists, Social workers and an operations administrative team. We support around 13,000 outpatient visits annually, accounting for 14% of total pediatric outpatient visits in our hospital.22 This amounts to 35% of the national DBP population served annually in a public institution.23 We receive referrals from primary care services, community pediatricians from Singapore and from the Southeast Asia region. The majority of our patient population receive government-subsidized care. Our referrals are triaged and first visits are seen within 1–2 months of referral.21

2. Methods

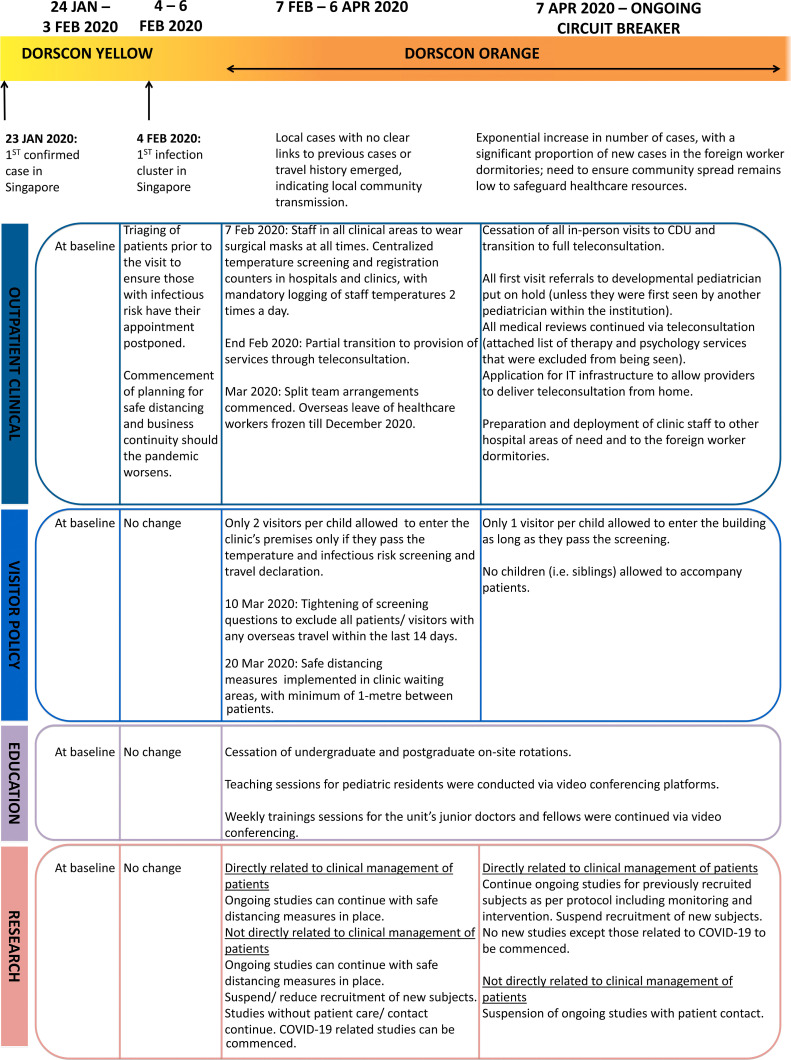

Our CDU team's innovative response to this pandemic was in conjunction with the hospital and national public health response as per the ‘Disease Outbreak Response System Condition’ (DORSCON).24 Fig. 1 summarizes CDU's dynamic changes and implementation of workflow processes. Key elements of this are discussed below.

Figure 1.

Child development unit's response to the change in DORSCON status.

2.1. Providing continuity of care via teleconsultation

Prior to the pandemic, our Ministry of Health had only approved the use of telemedicine in limited settings but not for routine service delivery.25 Teleconsultations were not previously offered in our DBP services. Within 3 weeks of escalation of our national pandemic alert level from yellow to orange (refer to A Singapore Government Agency Website, gov.sg, for more details on DORSCON and what the alert levels yellow, orange mean),24 CDU offered teleconsultations (phone/video conferencing) in lieu of physical visits to a selected group of patients. Children whose diagnoses were clear, with intervention plans in place and who did not need a direct in-person developmental or physical assessment were deemed suitable for teleconsultation.

The following group of children were deemed unsuitable for teleconsultation; a) children who were being seen for the first time, b) children whose provisional diagnosis was unclear, c) children who required physical examinations, and d) children whose appointments were scheduled to discuss their psychological diagnostic assessment results.

When the ‘CB’ was implemented, medical services that were not directly involved in caring for acutely ill patients were advised to cease patients' physical appointments. We then established new workflows and provided full services via teleconsultations to all our existing patients. Security protocols were established and teleconsultation practices26 standardized to ensure that patient privacy and security were upheld.27

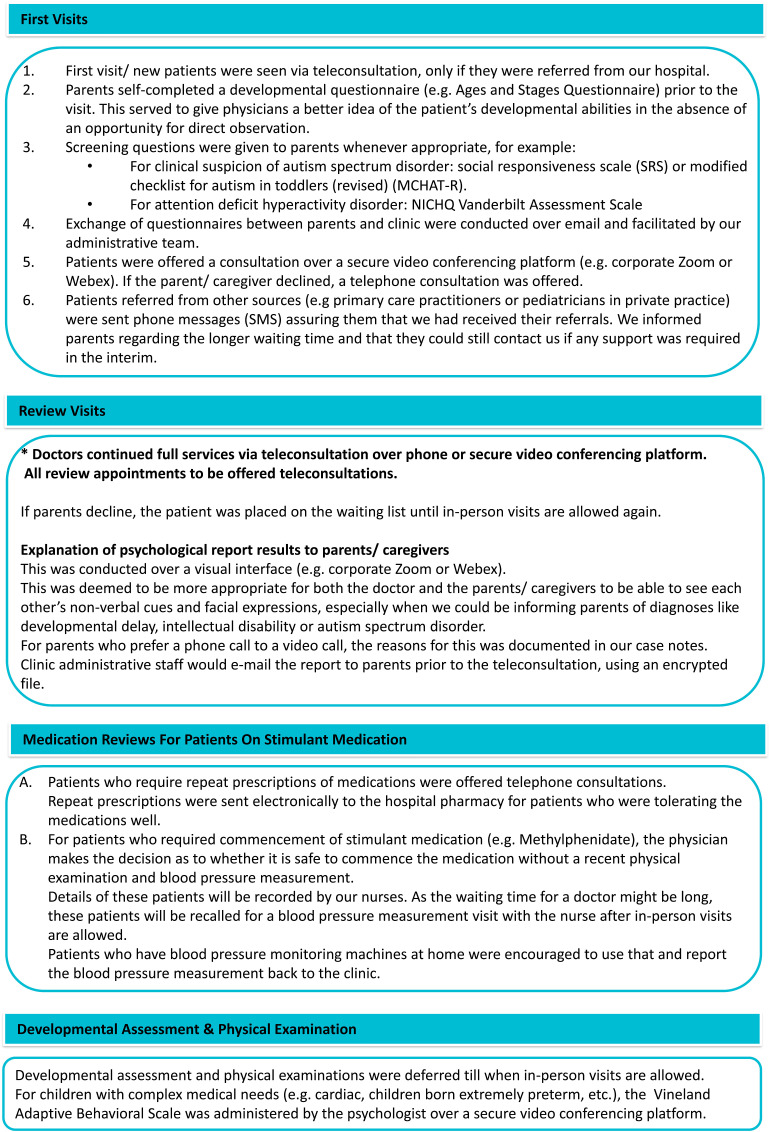

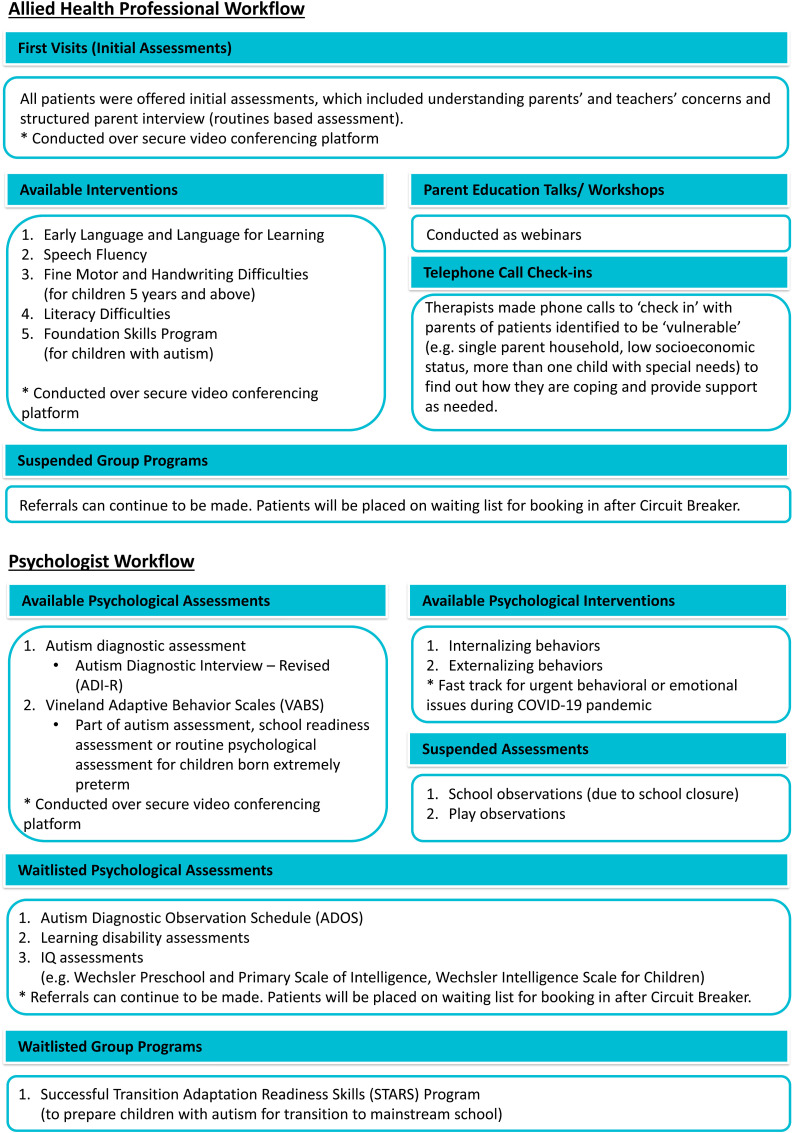

Detailed workflows were created for each subspecialty as shown in Fig. 2 (developmental pediatricians) and Fig. 3 (allied health professionals, psychologists). We continued to receive referrals to our services at similar rates. We were not able to offer teleconsultation services to new patients referred from community as per our Ministry of Health teleconsultation directive.26 Physical Visits for these patients were put on a priority waitlist and deferred to when in-person consultations were allowed after ‘CB’ restrictions. Older children (>7 years of age), who would usually transit to school-based programs in the community or to child psychiatry services, continued to be served by us to maintain separation between different services.

Figure 2.

Child development unit doctor workflow during ‘Circuit Breaker’.

Figure 3.

Child development unit allied health professional and psychologist workflow during ‘Circuit Breaker’.

2.2. Ensuring safety of staff, patients and their families during the pandemic

We reduced the number of personnel within clinic premises. Non-essential personnel (e.g., students, clinical observers) had to suspend their clinical attachments to the clinic. Staff were encouraged to work from home whenever possible (e.g., psychologists could write their reports from home). A hospital virtual private network (VPN) account was obtained for all staff to facilitate access to clinical notes at home.

Safe distancing was enforced in the clinic. Measures such as mandatory donning of surgical face masks, logging of staff's temperature twice daily and mandatory reporting of staff sickness were instituted. We split into two teams (one at each community site) and stopped going to the main hospital site to minimize cross–site interaction.

Beyond segregating staff, patients were also only allowed to receive intervention from one site. If patients had to cross over to the other site for clinical reasons, we instituted a mandatory 14-day interval between visiting the two sites for patients. Phone calls were made to patients one week prior to the appointment to obtain information on travel history, fever, respiratory symptoms, and contact with any confirmed case of COVID-19 within the previous 14 days. Appointments were postponed if any risk factors were reported. On the day of their clinic appointment, temperature and questionnaire screening was performed on all patients and visitors. Each child was only allowed to have one accompanying adult during the visit. They were advised to sanitize their hands with alcohol disinfectant and to wear a surgical facemask at all times.

Social distancing measures were implemented in the waiting area. Clinic rooms and premises were cleaned more frequently. Table tops, chairs, assessment tools and surfaces patients contacted were cleaned with alcohol disinfectant after each patient. All communal toys were removed and the playroom was closed. A room in the clinic was designated as an ‘isolation’ room for patients with symptoms suspicious of COVID-19. Patients would remain in this room while awaiting transfer to the designated hospital.

2.3. Maintaining research and education as part of a tertiary institution

In line with official institution-level advisories, only research studies that would directly impact clinical care were allowed.28 Apart from one study examining different modalities of early intervention in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, the rest of our studies were on hold but the team continued work on non-physical aspects of research such as data analysis. We continued teaching sessions for fellows via video conferencing.

2.4. Additional support for patient and families

During the CB period, schools, preschools, childcare and early intervention centers ceased operations temporarily.29 Through our clinic consultations, parents gave feedback about the stress they experienced during this period. Parents had difficulties working from home while managing children with additional needs. Home Based Learning (HBL) delivered online by schools was also a source of stress for parents as children with additional needs required parents to facilitate these sessions at home.

Children with additional needs are at increased risk of abuse and neglect.17 With the pandemic, this risk is stated to be even higher.30 , 31 Beyond providing routine clinical care, we actively reached out to our patients via weekly emails and mobile phone messages, providing them with the strategies to help them cope. For a selected group of especially vulnerable families, (e.g., financial difficulties, multiple children with special needs) we initiated an outreach program with targeted phone calls. As per routine practice, our clinic hotlines and email were open so patients could contact us with any concerns or queries. We also set up an urgent referral process to fast-track referrals from the pediatric clinics at the main hospital, to address mood and behavioral problems resulting from or exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.5. Outreach to the community

We collaborated with the Ministry of Health and other public health institutions to create visual supports32 to help children prepare themselves for COVID-19 related healthcare encounters. We created web resources based on needs highlighted by parents. These were suitable for neurotypical and neuro-atypical children. These resources were housed on a dedicated COVID-19 page on the hospital website33 and made available for free to the general public. They were also published on our hospital intranet for use by any clinician within the hospital.

2.6. Taking care of staff welfare

We recognized that staff welfare and morale were essential.34 , 35 Staff in our unit experienced stress in these areas: constant changes to clinic operations, supporting distressed parents, anxiety about the risks of being infected with COVID-19 and home stressors, e.g., supporting their children with HBL. A social worker was designated as CDU's ‘mental health champion’. She actively approached team members to find out how they were coping and provided support. Our bimonthly virtual team meetings also served as an opportunity for social interaction and mutual support.

3. Results

3.1. Patient numbers and responses to changes in our clinical workflows

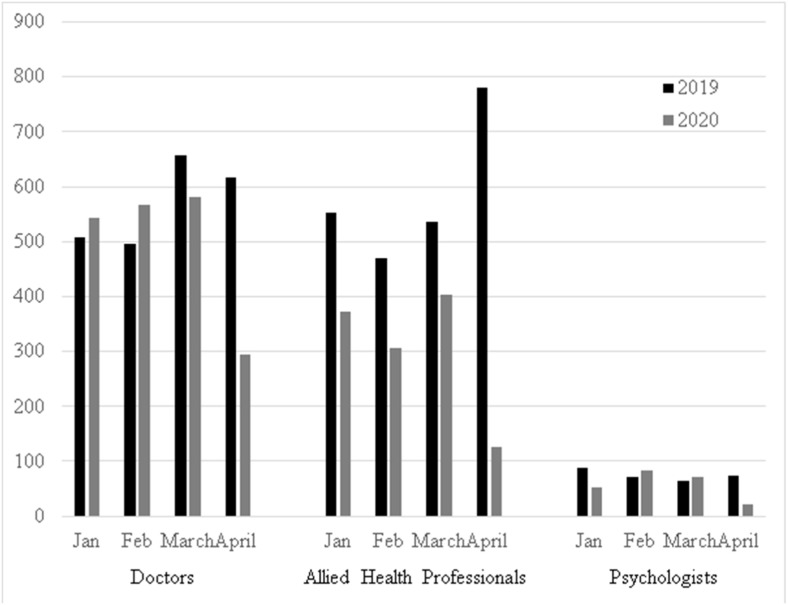

Fig. 4 shows the number of patients seen in January–April 2020, compared to the same period last year. While there was a significant drop in April after the ‘CB’ was announced, the total number of patients seen between January and March was comparable despite shifting to teleconsultation services. The 50% drop in consultations corresponded to 50% of medical staff being deployed to acute hospital settings, together with inability to undertake teleconsultations for new patients referred as per our Ministry of Health guidelines. Other contributors to the reduction in AHP and psychology patient numbers included: a 2-week break for designing a detailed workflow for tele-intervention, suspension of group therapy sessions and inability to perform certain psychological assessments.

Figure 4.

Patients numbers in our DPB Clinic from January to April 2020 (COVID-19 pandemic) compared to a similar period in 2019 (non-pandemic period).

It is too early to determine the full extent of the long-term mental health and psychosocial impact of COVID-19 and lockdown measures. Much of it is still speculative.36 In the same vein, it is difficult to determine the real benefit of adaptive measures to stay in touch with families and their children served by our DBP service. We believe that continuing our services to support our families will help them during these unprecedented times.

Teleconsultations were, overall, well received by parents. Informal feedback on parents’ perceptions showed that the vast majority of caregivers felt that their concerns were well addressed by the providers during the teleconsultations and they were open to continuing teleconsultations for their child even after the pandemic.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has required a collective and swift response from our team. Despite cutting back on physical visits, we continued to deliver clinical services. Preliminary analysis of results of a study looking at the experiences of parents and providers suggests overall positive results.

4.1. Challenges faced

4.1.1. Virtual access and IT devices

Prior to the pandemic, our electronic medical records could only be accessed within the clinic premises. To allow effective teleconsultations from home, we had to obtain VPN access and supporting devices (hospital laptops) for our staff. Due to resource constraints, we were only partially successful in obtaining devices even though VPN access was obtained for all. The rest of the staff had to travel to CDU to deliver the teleconsultations.

4.1.2. Inter-team communications and navigating change

Another challenge was coordinating the changes across the sub-divisions (pediatricians, psychologists, allied health, social workers, operational staff) within the clinic. The sub-division heads communicated frequently to alter clinical workflows in tandem with national pandemic response. The whole team met virtually fortnightly instead of monthly to discuss changes in clinical processes. Communicating the relevant operational changes to parents also involved calling or messaging individual patients due to the lack of a means of mass-dissemination of information for the parents we serve. This was labor and time intensive.

4.1.3. Rapid change from physical to teleconsultations

The acceptability and adoption of teleconsultations was difficult for some patients and health professionals alike. In fact, many health professionals felt that the practice of DBP requires a “soft touch” and face-to-face consultations allowed better emotional connection with families. It was also harder to assess family support and welfare of children, especially in the context of potential neglect and harm via teleconsultation. There were sporadic cases where children were found to be at risk of potential neglect and harm during teleconsultation. These families were linked to intensive community support. Parents who struggled with technology access or had poor literacy were not able to access teleconsultations. This is also reported by Nittari et al.37 We feel there is a need to look at financial and technology support grants for low-income families. Shared health-social-education service databases would be useful to understand which families and children are most vulnerable and require most assistance.

5. Future plans

This unprecedented pandemic has revealed a few significant learning points and shifts in the way we think about the systems around children with developmental disabilities. With the COVID-19 pandemic being prolonged, new norms of practice will be necessary even when ‘CB’ restrictions are eased. In the upcoming months, teleconsultations are likely to continue for the subset of patients who are suitable for it. Face-to-face consultations may be prioritized for patients who need psychological or developmental assessments, and families who need significant support (e.g., low income, technologically illiterate, multiple kids with special needs, etc.). We are exploring the possibility of conducting diagnostic assessment for autism using video-based observations and other validated forms of symptom-based scoring.38 Additionally, we have also become a first adopter site of telehealth under the Ministry of Health Singapore.

Early intervention services may need to be innovative, and likely to offer a combination of some clinic visits alternating with some web-based coaching. A community of early interventionists could combine expertise in sharing and making widely available web-based intervention coaching and curriculum based on highest and best standards.39 Making these resources accessible for free would benefit countries that struggle to put together such material for their most needy families. In fact, our experience with non-English speaking families has taught us that most of the currently available web-based resources are not beneficial for these patients due to the language barrier. We will need to continue to adapt and refine our workflow processes as we learn together with our patients and their families during this pandemic journey.

6. Conclusion

We are able to continue our DBP services during this pandemic. Teleconsultation services, IT infrastructure, targeted staff training and parent education via video interface has played a key role in this process so far. We hope that this adaptive workflow (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3) could provide a model that could be replicable to other similar DBP centers globally with center-specific modifications in order to continue their DBP services. We believe it is essential to continue our advocacy and support for families with children with special needs even during the pandemic when public health and safety needs outweigh the less urgent intervention needs of children with developmental disabilities. Given that this pandemic is likely to be long drawn, our unit remains robust and ready to constantly adjust these workflows and make adaptations as we go along to best serve our patients and their families.

Funding statement

None.

Ethical information

Ethical approval was not required as per local institutional review board guidelines.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgement

No funding was required for this study. All authors contributed to the design and implementation of the research into clinical practice and writing of the manuscript. The author would like to thank the team at the NUH CDU for the contributions to the workflows implemented and Dr Dimple Rajgor formatting and submission of the manuscript for publication. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020.https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chia R.G., Moynihan R. 2020. This alarming map shows where the coronavirus has spread in Singapore, one of the worst-hit areas outside of China.https://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-singapore-map-shows-spread-worst-hit-outside-china-2020-2?IR=T Feb 14th 2020 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health Singapore . April 3rd 2020. Circuit breaker to minimise further spread of COVID-19.https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/circuit-breaker-to-minimise-further-spread-of-covid-19 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Philips K., Uong A., Buckenmyer T., Cabana M.D., Hsu D., Katyal C. Rapid implementation of an adult Coronavirus disease 2019 unit in a children's hospital. J Pediatr. 2020;222:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan R.M.R., Ong G.Y., Chong S.L., Ganapathy S., Tyebally A., Lee K.P. Dynamic adaptation to COVID-19 in a Singapore paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2020;37:252–254. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-209634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Government of Canada . 22 Apr 2020. COVID-19 pandemic guidance for the health care sector.https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/health-professionals/covid-19-pandemic-guidance-health-care-sector.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scherzer A.L., Chhagan M., Kauchali S., Susser E. Global perspective on early diagnosis and intervention for children with developmental delays and disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:1079–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04348.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson G., Rogers S., Munson J., Smith M., Winter J., Greenson J. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e17–e23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emanuel E.J., Persad G., Upshur R., Thome B., Parker M., Glickman A. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Keeffe M., Macaulay C. Diagnosis in developmental–behavioural paediatrics: the art of diagnostic formulation. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48:E15–E26. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wade V.A., Eliott J.A., Hiller J.E. Clinician acceptance is the key factor for sustainable telehealth services. Qual Health Res. 2014;24:682–694. doi: 10.1177/1049732314528809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lake A., Chan M. Putting science into practice for early child development. Lancet. 2015;385:1816–1817. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61680-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soares N.S., Langkamp D.L. Telehealth in developmental-behavioral pediatrics. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33:656–665. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182690741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnett W.S., Escobar C.M. Research on the cost effectiveness of early educational intervention: implications for research and policy. Am J Community Psychol. 1989;17:677–704. doi: 10.1007/BF00922734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conroy K., Rea C., Kovacikova G.I., Sprecher E., Reisinger E., Durant H. Ensuring timely connection to early intervention for young children with developmental delays. Pediatrics. 2018;142 doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonis S. Stress and parents of children with autism: a review of literature. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2016;37:153–163. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1116030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrigo J.L., Berkovits L.D., Cederbaum J.A., Williams M.E., Hurlburt M.S. Child abuse and neglect re-report rates for young children with developmental delays. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;83:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . September 18, 2019. Childhood maltreatment among children with disabilities.https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandsafety/abuse.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiao W.Y., Wang L.N., Liu J., Fang S.F., Jiao F.Y., Pettoello-Mantovani M. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Pediatr. 2020;221:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schieve L.A., Gonzalez V., Boulet S.L., Visser S.N., Rice C.E., Van Naarden Braun K. Concurrent medical conditions and health care use and needs among children with learning and behavioral developmental disabilities, National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2010. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho L.Y. Child development programme in Singapore 1988 to 2007. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2007;36:898–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Straits Times Singapore . 2019. New NUH paediatric centre houses all outpatient services for children under one roof.https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/new-nuh-paediatric-centre-houses-all-outpatient-services-for-children-under-one Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lourdes M.D. 2020. Helping children with developmental needs have a better tomorrow.https://www.singhealth.com.sg/news/medical-news/helping-children-with-developmental-needs SingHealth Medical News. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 24.A Singapore Government Agency Website . 06 Feb 2020. What do the different DORSCON levels mean.https://www.gov.sg/article/what-do-the-different-dorscon-levels-mean Published on. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministry of Health Singapore . 2018. Licensing experimentation and adaptation programme (Leap) - a MOH regulatory sandbox.https://www.moh.gov.sg/home/our-healthcare-system/licensing-experimentation-and-adaptation-programme-(leap)---a-moh-regulatory-sandbox Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health Singapore . 18 April 2018. Telemedicine and issuance of online medical certificates.https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/default-document-library/joint-smc-and-moh-circular-on-teleconsultation-and-mcs.pdf Smc circular NO. 2/2018. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National telemedicine guidelines. Jan 2015. https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/resources-statistics/guidelines/moh-cir-06_2015_30jan15_telemedicine-guidelines-rev.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Health Sciences Authority (HSA) Singapore . 27 Mar 2020. Guidance on the conduct of clinical trials in relation to the COVID-19 situation.https://www.hsa.gov.sg/docs/default-source/hprg-io-ctb/hsa_ctb_covid-19_guidance_for_clinical_trials_27mar2020.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Education Singapore . April 03, 2020. Schools and institutes of higher learning to shift to full home-based learning; preschools and student care centres to suspend general services.https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/press-releases/schools-and-institutes-of-higher-learning-to-shift-to-full-home-based-learning-preschools-and-student-care-centres-to-suspend-general-services Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphreys K.L., Myint M.T., Zeanah C.H. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;145 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Straits Times Singapore . May 14 2020. Coronavirus: more cases of family violence during circuit breaker; police to proactively help victims.https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/courts-crime/coronavirus-more-cases-of-family-violence-during-circuit-breaker-police-to Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministry of Health Singapore. Infographics. Available at https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/resources. Accessed July 2 2020.

- 33.National University Hospital. COVID-19 resources for parents and caregivers. Available at https://www.nuh.com.sg/our-services/Specialties/Paediatrics/pages/covid-19-resources-for-parents-and-caregivers.aspx. Accessed July 2, 2020.

- 34.Schulte E.E., Bernstein C.A., Cabana M.D. Addressing faculty emotional responses during the Coronavirus 2019 pandemic. J Pediatr. 2020;222:13–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Q., Liang M., Li Y., Guo J., Fei D., Wang L. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar A., Nayar K.R. COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. J Ment Health. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2020.1757052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nittari G., Khuman R., Baldoni S., Pallotta G., Battineni G., Sirignano A. Telemedicine practice: review of the current ethical and legal challenges. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26:1427–1437. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juárez A.P., Weitlauf A.S., Nicholson A., Pasternak A., Broderick N., Hine J. Early identification of ASD through telemedicine: potential value for underserved populations. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48:2601–2610. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3524-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsons D., Cordier R., Vaz S., Lee H.C. Parent-mediated intervention training delivered remotely for children with autism spectrum disorder living outside of urban areas: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e198. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]