Abstract

Cell-free fat extract (CEFFE), the liquid fraction derived from fat tissues, is enriched with a variety of growth factors and possesses pro-angiogenic, anti-apoptotic, and anti-oxidative properties. The aim of this study was to determine if CEFFE could accelerate chronic wound healing in mice with diabetes and investigate its underlying mechanisms. A model of circular full-thickness wound (6 mm diameter) was produced in the central dorsal region of spontaneous type 2 diabetes mellitus db/db mice. The mice were divided to three groups depending on dosage of CEFFE administered for the study; high dose CEFFE group (CEFFEhigh; administered 2.5 ml/kg/day via subcutaneous injection for six days), low dose CEFFE group (CEFFElow; administered 2.5 ml/kg/day via subcutaneous injection for three days), and a control group receiving phosphate buffer solution. Wound closure was evaluated on day 3, 7, 10, and 14 post-operation. Histological analyses, including hematoxylin-eosin staining and Masson’s trichrome staining and immunohistological staining of anti-CD31 and anti-CD68, were also performed. Moreover, the effects of CEFFE on proliferation, migration, and tube formation of human immortal keratinocyte cells (HaCaT) and human vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) were tested in vitro. The results showed that the local injection of CEFFE significantly accelerated wound healing in mice with diabetes. CEFFE improved re-epithelization and collagen secretion, promoted angiogenesis, and inhibited inflammatory macrophage infiltration in vivo. CEFFE also promoted HaCaT proliferation and migration and enhanced tubular formation in cultured HUVEC. It was concluded that CEFFE accelerates wound healing through pro-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory activities.

Keywords: Fat extract, chronic wound healing, pro-angiogenesis, anti-inflammation, growth factors, cell-free therapy

Introduction

Chronic refractory wounds in patients with diabetes remain a serious clinical problem. Chronic wounds can cause secondary injuries, such as infections, chronic foot ulcers, and limb amputations, which can seriously affect the patient’s quality of life [1,2]. To promote wound healing, many methods have been attempted, such as debridement, antibiotic treatment, tissue engineering materials, and cell therapy [3-6]. Among these, stem cell-based therapy has been considered a promising approach for the treatment of chronic wounds [7]. Adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs), a type of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), have particularly shown various advantages in wound healing [8].

ASCs promote wound healing by various mechanisms. One of these relies on the unique plasticity of ASCs. Previous studies have proved that ASCs can differentiate into a variety of cells related to wound healing, such as fibroblasts, keratinocytes, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells [9,10]. Another major mechanism proposed is through the paracrine secretion of factors that promote differentiation and proliferation of stem cells and its neighboring cells [10-13]. Through the paracrine secretion of various growth factors, including fibroblast growth factor 2 (bFGF), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), ASCs are able to accelerate the process of wound healing by recruiting endogenous cells, inducing the proliferation of fibroblasts and keratinocytes, and stimulating neovascularization at the site of injury [9,12,14,15]. Additionally, ASCs also possess anti-apoptotic and anti-oxidant properties, which can further improve the process of wound healing [9,12,14].

Although ASCs are effective in improving wound healing, restrictions are still encountered in their application. Primarily, donor specificities, such as age and gender, can affect ASC potentials, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and the capacity to promote angiogenesis and prevent apoptosis [16,17]. The health status of donors also affects the quality of ASCs produced. Previous studies conducted in mice demonstrated that the presence of diabetes in the rodents significantly reduced the production of growth factors, such as HGF, VEGF, and IGF-1, altered intrinsic properties of ASCs, and impaired their function [18,19]. In addition to ASC sources, limitations also exist in the cell culturing techniques, including safety and quality of in vitro cell expansion, along with phenotypic, functional, and genetic instabilities [20-22]. Further, to culture cells for clinical therapies, Food and Drug Administration-approved techniques and facilities are to be employed, along with the time required for the cells to culture [23].

The adipose tissue, an abundant source of ASCs, secretes large amounts of bFGF, VEGF, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), which promote angiogenesis and adipogenesis [24,25]. This indicates that the adipose tissue is inherently enriched with a variety of bioactive factors that may be directly isolated for clinical application without cell isolation or cultivation. Cell-free fat extract (CEFFE), the liquid fraction derived from fat tissue using a mechanical approach to remove cellular components and lipid remnants, was first described in our previous study [26]. CEFFE analysis demonstrated that it contained a large number of cytokines and growth factors, including IGF-1, TGF-β1, HGF, VEGF, PDGF, bFGF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) [27]. In subsequent assays, we found that the CEFFE possessed not only the capacity for angiogenesis for the treatment of limb ischemia and skin flap survival [26,27], but also anti-apoptotic and anti-oxidative abilities [28,29].

Based on the above findings, it was hypothesized that CEFFE might accelerate chronic wound healing. To test this hypothesis, this study evaluated the effects of CEFFE on wound healing in diabetic mice and investigated the underlying mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male C57BL/KsJ db/db mice (8 weeks, 36-40 g) were purchased from GemPharmatech Co. Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). These leptin receptor-deficient db/db mice represent a well-established type 2 diabetes animal model, which exhibits continuous hyperinsulinemia and high plasma glucose levels. The mice were housed in a well-ventilated holding room with a 12-h light-dark cycle at an ambient temperature of 23 ± 2°C and 70% humidity, with free access to water and food. All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Experiment Committee of Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine.

CEFFE preparation and characterization

CEFFE was prepared in accordance with a previously established method [26]. Briefly, human adipose tissue was obtained from healthy female donors who underwent liposuction. The tissue was rinsed with saline to remove red blood cells and centrifuged at 1200 × g for 3 min. The upper oily layer and lower fluid layer were then discarded, and the middle fat layer was harvested and mechanically emulsified. The emulsified fat was then frozen at -80°C and thawed at 37°C for further disruption of the cells in the fat tissue. After one cycle of the freeze/thaw process, the fat was centrifuged again at 2000 × g for 5 min and separated into four layers; the third aqueous layer containing CEFFE was collected and frozen at -80°C for experimental purposes. The protein concentrations of CEFFE were measured using a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

Wound model and treatment

Mice were randomly divided into three groups based on those receiving the high dose of CEFFE (CEFFEhigh; administered 2.5 ml/kg/day via subcutaneous injection for six days), the low dose of CEFFE (CEFFElow; administered 2.5 ml/kg/day via subcutaneous injection for three days), or phosphate buffer solution (PBS, control group). All mice were subjected to general anesthesia using isoflurane gas. The dorsal area was shaved, and a depilatory cream was used to remove hair completely. Ophthalmic scissors were used to produce a circular full-thickness wound, 6 mm in diameter, on the central dorsal region of the mice. Digital images of the wound in all experimental mice were captured on day 0, 3, 7, 10, and 14. The area of the wounds was calculated and analyzed by tracing around the wound image margins using Image-Pro Plus software version 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA). Wound closure was expressed as a percentage area of the original wound area.

Histological staining

On the 14th postoperative day following wound creation, the wound and surrounding tissue (0.5 cm) were carefully excised, rinsed in PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. The samples were then sectioned and stained using hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome staining for histological analyses.

For immunohistological staining, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were incubated with rabbit anti-CD31 and anti-CD68 antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). To evaluate angiogenesis in the wound, CD31+ tubular structures were considered to be capillaries, and the capillary density in the wounded area, undergoing healing, was quantified. To analyze the inflammation condition of the wound, CD68+ cell numbers were calculated. Five random fields were selected from each sample, and three samples from each group were analyzed.

Western blot analysis

To further analyze the content of newly formed collagen in the wound, tissue lysates were extracted using a RiPA Lysis buffer (Millipore, USA) containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany). Equal amounts of protein (40 μg) were separated onto a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and subsequently transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Membranes were then blocked in TBS-T containing 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies as follows: Type I (COL-1) collagen (Abcam, ab6308, 1:500), Type III (COL-3) collagen (Abcam, ab6310, 1:500), or β-actin (Cell Signaling, 3700, 1:1000). After overnight incubation on a shaker at 4°C, samples were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA, USA). The protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham). The results were normalized to β-actin as appropriate.

Cell culture

Human immortal keratinocyte cells (HaCaT) and human vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). They were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Gland Island, NY, USA) and 1% antibiotics (penicillin 100 U/ml, streptomycin 100 U/ml) (Gibco, Gland Island, NY, USA). The culture medium was changed every second or third day, and the culture was maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Cell proliferation assay

HaCaT were seeded in 96-well plates (1 × 103 cells per well) and cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS for 24 h. The cells were then treated with three concentrations of CEFFE (50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 500 μg/ml total protein) for three days; untreated cells were used as a control. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA) was used for the cell proliferation assay. The absorbance spectrum was observed at 450 nm and recorded using a microplate reader (SpectraMAX i3x; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Cell migration assay

HaCaT were seeded in 6-well plates (5 × 105 cells per well) and grown to form a monolayer. Wounds were created by scratching the monolayer with a sterile pipette tip. The medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS. Three concentrations of CEFFE (50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 500 μg/ml total protein) were then added to the medium. Images of the wound were captured using a digital camera at 0 and 12 h after the samples were scratched. The wound size was measured using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The data is reported as a relative percentage of wounding healed.

Tube formation assay

A tube formation assay was performed in Matrigel (BD Biosciences). HUVEC were suspended in DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS. HUVEC were seeded onto 96-well plates coated with Matrigel (2 × 104 cells per well). The plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 8 h. Tube formation was photographed under a light microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The number of junctions that had formed was calculated using ImageJ software (NIH).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 19.0 statistical software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between the groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or non-parametric tests. Significance levels were set at *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

Results

Preparation and characterization of CEFFE

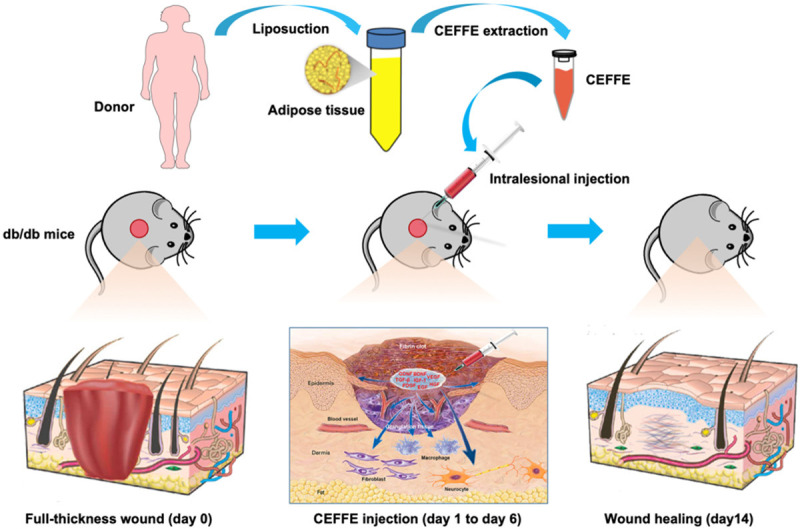

The schematic illustrations of extraction and administration of CEFFE are shown in Figure 1. Approximately 7 ml of pinkish CEFFE was attained from 50 ml of centrifuged lipoaspirate, consistent with the previous experiment [26]. The original total protein concentration of CEFFE was 5208.31 ± 413.35 μg/ml (n = 3) in this study.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of CEFFE promoting wound healing in db/db mice.

CEFFE improved wound healing in vivo

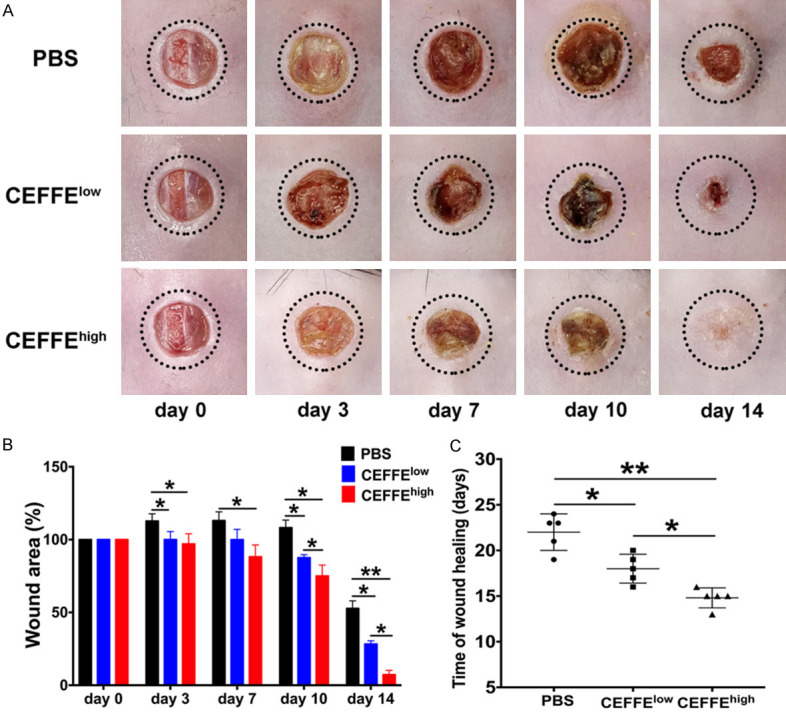

Digital photos of wounds in each of the groups were collected on day 0, 3, 7, 10, and 14, post-wounding (Figure 2A). Compared to the control, the size of the wounds in both groups treated with CEFFE decreased significantly from day 3. No significant difference was recorded between the two groups treated with CEFFE. On day 10 and 14, significant differences were observed between all three groups (Figure 2B). Aside from CEFFE administration significantly reducing healing time (Figure 2C), the average healing time also reduced from 22.00 ± 2.00 days (control group) to 18.00 ± 1.58 days (CEFFElow group) and 14.80 ± 1.09 days (CEFFEhigh group).

Figure 2.

Topical application of CEFFE accelerated wound healing in db/db mice. A. Representative images of wound healing in the PBS, CEFFEhigh, and CEFFElow groups. B. Percentage of original wound area in each group on day 0, 3, 7, 10, and 14 post-wounding. Quantitative analysis of wound closure indicated that the CEFFEhigh group exhibited the highest wound healing rate among all groups. C. Time taken for wound healing in db/db mice. CEFFEhigh group exhibited the shortest healing time among all groups. Data are represented as mean ± SD; n = 6, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Histological evaluation of wound tissue

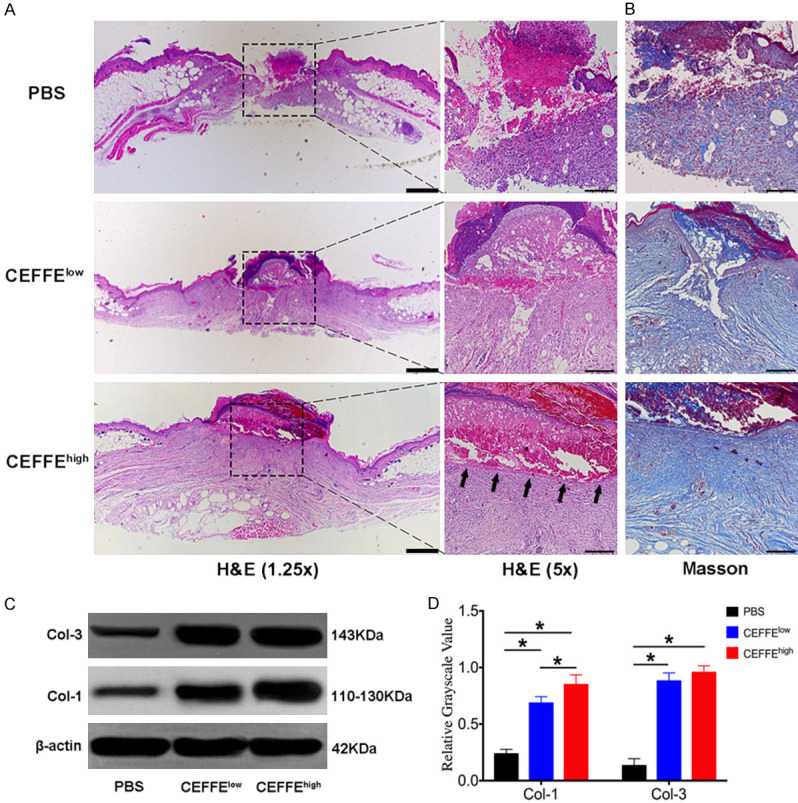

Microscopic analysis was conducted to assess the formation of granulation tissues and the re-epithelialization in H&E stained wound tissue sections (Figure 3A). Histological observations showed that on day 14, the wound in mice treated with CEFFEhigh showed intact continuous re-epithelialization (arrow-marked in Figure 3A), while almost no re-epithelialization was observed in the control group. Although new epithelia were present in mice treated with CEFFElow, they were not continuous.

Figure 3.

Topical application of CEFFE accelerated cutaneous wound closure, re-epithelialization, and collagen deposition in db/db mice. A. H&E staining for representative wound beds on day 14; re-epithelialization is indicated by arrows. Pictures were taken with a 1.25 × lens (scale bar: 200 μm) and 5 × lens (scale bar: 50 μm). B. Masson’s trichrome staining for representative wound beds after 14 days (collagen deposition is stained blue, scale bar: 50 μm). C. Type I (COL-1) and Type III (COL-3) collagen in the wound beds of each group were measured using the western blot technique. D. Relative quantification of COL-1 and COL-3 in wound beds of each group. Data are represented as mean ± SD; n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The regeneration of the dermis is mainly assessed by Masson’s trichrome staining because collagen is the most abundant fiber component of dermal connective tissues. Histological evaluation of the stained slides revealed that on day 14, the collagen deposition was enhanced in the granulation tissue of the wounds in both groups treated with CEFFE (collagen fiber stained blue) compared with the control group (Figure 3B). Western blot analysis of COL-1 and COL-3 in the wound beds further confirmed that mice treated with CEFFE had significantly more newly formed collagen fibers (Figure 3C and 3D, Supplemental Figure 1).

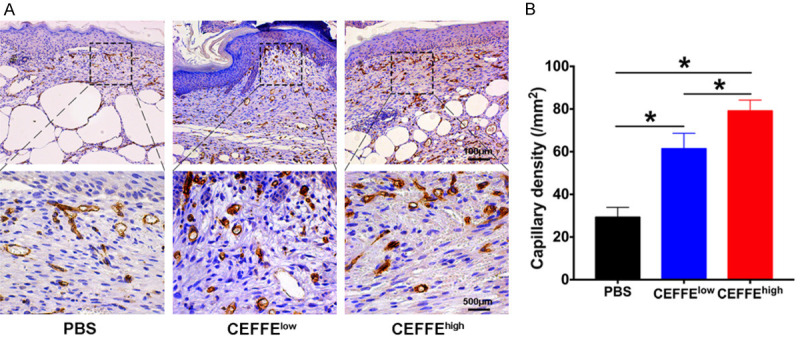

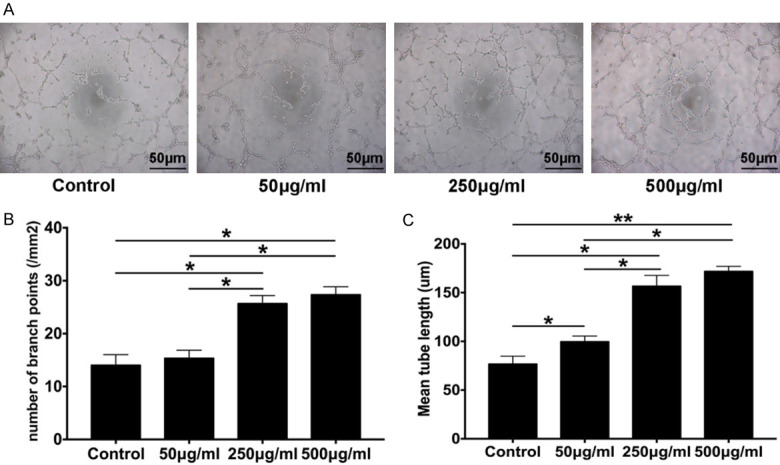

CEFFE increased angiogenesis in wounds

The angiogenic effect of CEFFE in vivo was evaluated by immunohistochemistry staining of CD31+ microvessels in the granulation tissue on day 14, post-operation. The capillary density significantly increased in both groups treated with CEFFE compared with that of the control. The capillary density in the CEFFEhigh group was higher than that of the CEFFElow group (Figure 4A and 4B).

Figure 4.

Pro-vascularization effect of CEFFE in diabetic wounds. A. Representative immunohistochemistry staining of CD31 on day 14 after wounding in the PBS, CEFFElow, and CEFFEhigh groups. B. Statistical analysis of CD31+ newly formed vessels. CEFFEhigh group showed significantly more increased capillary density than the CEFFElow and PBS groups. Data are represented as mean ± SD; n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

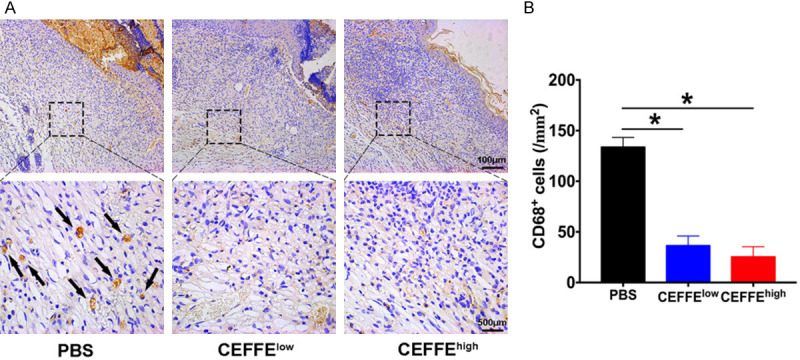

CEFFE decreased macrophage infiltration into wounds

To evaluate inflammatory cell infiltration, sections of wound tissue were examined on day 14 and stained for CD68 macrophage protein. The densities of CD68+ cells in the CEFFE groups were significantly lower compared to those in the control group. No significant difference was observed between the two CEFFE groups (Figure 5A and 5B).

Figure 5.

Anti-inflammatory effect of CEFFE in diabetic wounds. A. Immunostaining for CD68 in wound beds. The arrows indicate CD68+ inflammatory cells. B. Quantification of CD68+ cell density in each group. Both groups treated with CEFFE showed significantly lower CD68+ inflammatory cell infiltration in the wound beds compared to the control group. Data are represented as mean ± SD; n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

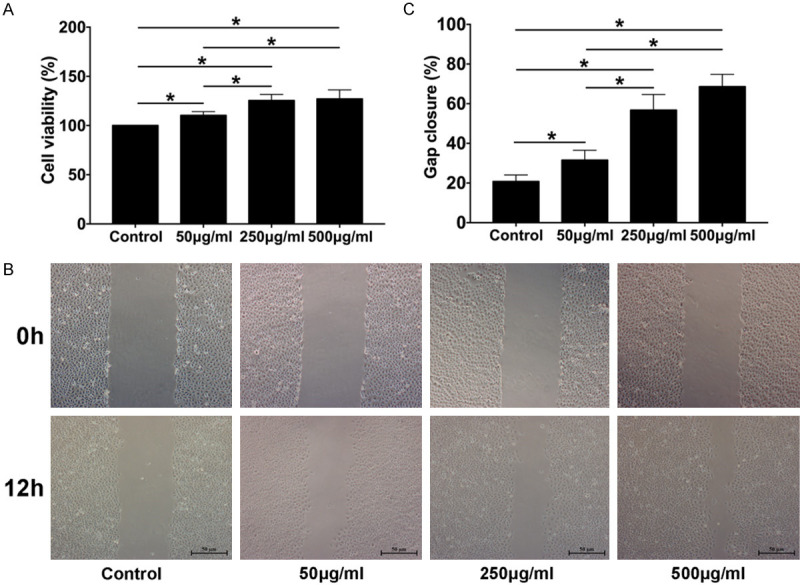

CEFFE promoted HaCaT proliferation and migration in vitro

To assess the pro-epithelialization capacity of CEFFE, the effects of CEFFE on HaCaT proliferation and migration were investigated in vitro. HaCaT were treated with CEFFE (50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 500 μg/ml total protein) for three days. The CCK-8 assay showed that CEFFE administration promoted HaCaT proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6A). The wound-healing assay was performed to test the effect of CEFFE on HaCaT migration. As shown in Figure 6B and 6C, after 12 hours of incubation, CEFFE enhanced HaCaT migration in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 6.

CEFFE promotes HaCaT proliferation and migration in vitro. A. HaCaT treated with CEFFE at the indicated concentrations (50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 500 μg/ml total protein); cell viability was assessed using cell counting kit-8, and the percentage of optical density relative to the control (0%) was calculated. B. HaCaT migration was evaluated using a cell migration assay (scale bar: 50 μm). C. Percentage of gap closure (over 12 h) was quantified. Data are shown as mean ± SD; n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

CEFFE improved HUVEC tube formation in vitro

To further confirm the pro-angiogenic activity of CEFFE in vitro, a tube formation assay was performed in which HUVEC were treated with CEFFE (50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 500 μg/ml total protein) for eight hours. A greater number of tubular structures were observed in the cells treated with CEFFE (Figure 7A). This finding was confirmed by calculating the number of branch points/mm2 and measuring the mean tube length in each concentration group (Figure 7B and 7C).

Figure 7.

CEFFE promotes endothelial cell tube formation in vitro. A. Tube formation of HUVEC at 8 h; cells were treated with CEFFE at the indicated concentrations (50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 500 μg/ml total protein) (scale bar: 50 μm). B. Assessment of the number of branch points/mm2 in each group. C. Quantification of the mean tube length. Data are shown as mean ± SD; n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

CEFFE is derived from the adipose tissue and enriched with a variety of growth factors, including IGF-1, TGF-β1, HGF, VEGF, PDGF, bFGF, BDNF, and GDNF. It is effective in the treatment of limb ischemia, flap survival, fat implantation, and anti-skin photo-aging [26-29]. In this study, we demonstrated that the subcutaneous injection of CEFFE significantly accelerated wound healing (Figure 2A) and granulation tissue formation in diabetic mice (Figure 3A). The possible mechanisms are likely through promoting the proliferation and migration of the epidermal cells, promoting angiogenesis, enhancing collagen secretion of dermal fibroblasts, and inhibiting excessive inflammatory responses.

Wound healing is a complex process, which is often artificially compartmentalized into three phases: inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [30]. The refractory wound in patients with diabetes mellitus is associated with an abnormality in one or more phases of the healing process. Angiogenesis during wound repair performs the crucial function of supplying essential nutrients and oxygen to the wound site, thus promoting granulation tissue formation [31,32]. Inhibited neovascularization is an important factor of refractory wound healing in diabetic subjects [33]. Previous studies have reported that CEFFE could promote neovascularization in normal animal models [26,28,29]; however, it was not clear if the same was true for diabetic animals. In this study, we observed an increased capillary density in wounds treated with CEFFE, evidenced by histological evaluation of anti-CD31 immunohistochemical staining (Figure 4A and 4B). The pro-angiogenic activity of CEFFE was further confirmed by the enhanced tube formation ability of HUVEC after treatment with CEFFE in vitro (Figure 7A-C). The pro-angiogenic effect of CEFFE in the wounds of diabetic subjects can be explained by the presence of high levels of the various growth factors. Continuous administration of CEFFE in the CEFFEhigh group resulted in faster healing and higher capillary density compared to the CEFFElow group (Figure 4A and 4B), indicating the cumulative effect of CEFFE therapy.

In the normal wound healing process, an inflammatory response should occur rapidly and be sustained for 3-4 days to allow for subsequent phases to occur [31,34,35]. This requires that inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, migrate to the wound area and phagocytize necrotic tissues and microorganisms. However, the inflammatory response in the wounds of diabetics is prolonged and heightened and contributes to impaired healing [36,37]. Regulating the inflammatory response could accelerate healing [38-40]. This study showed that treatment of wounds with CEFFE significantly reduces the infiltration of inflammatory macrophages in mice with diabetes (Figure 5A and 5B). Reduced inflammation could contribute to accelerated wound closure. It was observed that CEFFE could promote the transformation of macrophages from M1 to M2 phenotype (unpublished data). The mechanism by which this is achieved is still under investigation.

Keratinocytes are the most common cells present in the epidermis and form the outermost layer of the skin. Upon injury, keratinocytes migrate from the wound edge into the wound to re-epithelialize the damaged tissue and restore the epidermal barrier [41]. Non-migratory and hypo-proliferative keratinocytes result in epidermal thickening at the wound edge and non-healing wounds [42]. In this study, CEFFE promoted HaCaT proliferation and migration in a dose-dependent manner in vitro (Figure 6A-C). In addition, complete re-epithelization of the wound bed was observed in the CEFFEhigh group on day 14, compared to non-epithelization in the control. This further illustrated that CEFFE could promote keratinocyte proliferation and migration, even in a diabetic state of the host.

The skin contains up to 70% of collagen, which provides tensile strength to the tissue. The biosynthesis and deposition of new collagens and their subsequent maturation plays an important role in wound healing. Fibroblasts in the dermis initiate the synthesis of collagens and are responsible for the synthesis, deposition, and remodeling of collagens after migrating into wounds. In this study, a significant increase in the synthesis and deposition of collagen was observed in wound tissues treated with CEFFE. This was further supported by Masson’s trichrome staining (Figure 2A). Stimulation of fibroblast proliferation and ECM production by CEFFE had been demonstrated previously [29]; the possible reason for this is that growth factors such as HGF in CEFFE regulated the expression of genes related to collagen secretion such as COL-1, COL-3, FN, MMP-1, and MMP-3.

A hyperglycemic environment can lead to the structural and functional damage of nerve fibers, reduce the distribution of fibers in the skin, and inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of functional cells, thus interfering with wound healing in patients with diabetes [43,44]. Repair and regeneration of nerves in wound healing is important in patients with diabetes, considering that there are many nerve-related growth factors in CEFFE, including BDNF and GDNF [27]; the presence of newborn nerves in the tissue of the healed skin was speculated. However, no nerve tissues were observed using immunohistochemistry in this study. This may be due to technical problems (data not shown). The regeneration of nerves in the wounds after treatment with CEFFE can be investigated in future studies.

Under a diabetic condition, wound healing is impaired due to hyperglycemia-induced excessive reactive oxygen species production. This can lead to an imbalanced anti-oxidant defense system generating superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidases [45,46]. Accordingly, anti-oxidants partly improve the healing in skin wounds of diabetics [47]. It was demonstrated that, in some cases of injury, ointments containing SOD could promote wound healing. Previously it was demonstrated that CEFFE had potent anti-oxidant properties to protect the skin from photo-aging [29]. Hence, it was speculated that CEFFE enhanced the induction of anti-oxidant levels at an initial stage of healing, which might act as another contributing factor to its healing property.

In summary, our study demonstrated that CEFFE could improve the healing of chronic wounds in mice with diabetes. This is potentially through the pro-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory activity of CEFFE. The presence of a variety of growth factors in CEFFE could explain its effects on the function of epidermal cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and macrophages. CEFFE could potentially be used as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of chronic wounds in patients with diabetes. Further studies are still necessary to identify key factors and signaling pathways associated with the wound-healing effect of CEFFE to provide the basis for its clinical application.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [81771993], the National Key Research and Development Program of China [2016YFC1101400], and Shanghai Collaborative Innovation Program on Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research, 2019CXJQ01.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Greenhalgh DG. Wound healing and diabetes mellitus. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0094-1298(02)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung PC. Diabetic foot ulcers - a comprehensive review. Surgeon. 2007;5:219–231. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(07)80007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacNeil S. Progress and opportunities for tissue-engineered skin. Nature. 2007;445:874–880. doi: 10.1038/nature05664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Menocal L, Shareef S, Salgado M, Shabbir A, Van Badiavas E. Role of whole bone marrow, whole bone marrow cultured cells, and mesenchymal stem cells in chronic wound healing. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:24. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin CD, Allori AC, Macklin JE, Sailon AM, Tanaka R, Levine JP, Saadeh PB, Warren SM. Topical lineage-negative progenitor-cell therapy for diabetic wounds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1341–1351. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318188217b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumberg SN, Berger A, Hwang L, Pastar I, Warren SM, Chen W. The role of stem cells in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;96:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassanshahi A, Hassanshahi M, Khabbazi S, Hosseini-Khah Z, Peymanfar Y, Ghalamkari S, Su YW, Xian CJ. Adipose-derived stem cells for wound healing. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:7903–7914. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shingyochi Y, Orbay H, Mizuno H. Adipose-derived stem cells for wound repair and regeneration. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1285–1292. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1053867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebrahimian TG, Pouzoulet F, Squiban C, Buard V, Andre M, Cousin B, Gourmelon P, Benderitter M, Casteilla L, Tamarat R. Cell therapy based on adipose tissue-derived stromal cells promotes physiological and pathological wound healing. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:503–510. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.178962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rehman J, Traktuev D, Li J, Merfeld-Clauss S, Temm-Grove CJ, Bovenkerk JE, Pell CL, Johnstone BH, Considine RV, March KL. Secretion of angiogenic and anti-apoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation. 2004;109:1292–1298. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121425.42966.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim WS, Park BS, Sung JH, Yang JM, Park SB, Kwak SJ, Park JS. Wound healing effect of adipose-derived stem cells: a critical role of secretory factors on human dermal fibroblasts. J Dermatol Sci. 2007;48:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanton MW, Hadad I, Johnstone BH, Mund JA, Rogers PI, Eppley BL, March KL. Adipose stromal cells and platelet-rich plasma therapies synergistically increase revascularization during wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:56S–64S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318191be2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nie C, Yang D, Xu J, Si Z, Jin X, Zhang J. Locally administered adipose-derived stem cells accelerate wound healing through differentiation and vasculogenesis. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:205–216. doi: 10.3727/096368910X520065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerqueira MT, Pirraco RP, Santos TC, Rodrigues DB, Frias AM, Martins AR, Reis RL, Marques AP. Human adipose stem cells cell sheet constructs impact epidermal morphogenesis in full-thickness excisional wounds. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:3997–4008. doi: 10.1021/bm4011062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shu W, Shu YT, Dai CY, Zhen QZ. Comparing the biological characteristics of adipose tissue-derived stem cells of different persons. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:2020–2026. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu W, Niklason L, Steinbacher DM. The effect of age on human adipose-derived stem cells. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:27–37. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182729cfc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cianfarani F, Toietta G, Di Rocco G, Cesareo E, Zambruno G, Odorisio T. Diabetes impairs adipose tissue-derived stem cell function and efficiency in promoting wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2013;21:545–553. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Menocal L, Salgado M, Ford D, Van Badiavas E. Stimulation of skin and wound fibroblast migration by mesenchymal stem cells derived from normal donors and chronic wound patients. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1:221–229. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fossett E, Khan WS. Optimising human mesenchymal stem cell numbers for clinical application: a literature review. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:465259. doi: 10.1155/2012/465259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neri S, Bourin P, Peyrafitte JA, Cattini L, Facchini A, Mariani E. Human adipose stromal cells (ASC) for the regeneration of injured cartilage display genetic stability after in vitro culture expansion. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Huang H, Xu X. Biological characteristics and karyotiping of a new isolation method for human adipose mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Tissue Cell. 2017;49:376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.You HJ, Han SK. Cell therapy for wound healing. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:311–319. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.3.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pallua N, Pulsfort AK, Suschek C, Wolter TP. Content of the growth factors bFGF, IGF-1, VEGF, and PDGF-BB in freshly harvested lipoaspirate after centrifugation and incubation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:826–833. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318199ef31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarkanen JR, Kaila V, Mannerstrom B, Raty S, Kuokkanen H, Miettinen S, Ylikomi T. Human adipose tissue extract induces angiogenesis and adipogenesis in vitro. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:17–25. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu Z, Cai Y, Deng M, Li D, Wang X, Zheng H, Xu Y, Li W, Zhang W. Fat extract promotes angiogenesis in a murine model of limb ischemia: a novel cell-free therapeutic strategy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:294. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1014-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai Y, Yu Z, Yu Q, Zheng H, Xu Y, Deng M, Wang X, Zhang L, Zhang W, Li W. Fat extract improves random pattern skin flap survival in a rat model. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39:NP504–NP514. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng H, Yu Z, Deng M, Cai Y, Wang X, Xu Y, Zhang L, Zhang W, Li W. Fat extract improves fat graft survival via pro-angiogenic, anti-apoptotic and pro-proliferative activities. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:174. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1290-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng M, Xu Y, Yu Z, Wang X, Cai Y, Zheng H, Li W, Zhang W. Protective effect of fat extract on UVB-induced photoaging in vitro and in vivo. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:6146942. doi: 10.1155/2019/6146942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baum CL, Arpey CJ. Normal cutaneous wound healing: clinical correlation with cellular and molecular events. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:674–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31612. discussion 686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Cellular and molecular basis of wound healing in diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1219–1222. doi: 10.1172/JCI32169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan C, Nigam Y. Naturally derived factors and their role in the promotion of angiogenesis for the healing of chronic wounds. Angiogenesis. 2013;16:493–502. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falanga V. Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot. Lancet. 2005;366:1736–1743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Chen J, Kirsner R. Pathophysiology of acute wound healing. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stadelmann WK, Digenis AG, Tobin GR. Physiology and healing dynamics of chronic cutaneous wounds. Am J Surg. 1998;176:26S–38S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood S, Jayaraman V, Huelsmann EJ, Bonish B, Burgad D, Sivaramakrishnan G, Qin S, DiPietro LA, Zloza A, Zhang C, Shafikhani SH. Pro-inflammatory chemokine CCL2 (MCP-1) promotes healing in diabetic wounds by restoring the macrophage response. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu YS, Chen SN. Extracted triterpenes from antrodia cinnamomea reduce the inflammation to promote the wound healing via the STZ inducing hyperglycemia-diabetes mice model. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:154. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S, Shi J, Zhang M, Chen Y, Wang X, Zhang L, Tian Z, Yan Y, Li Q, Zhong W, Xing M, Zhang L, Zhang L. Mesenchymal stem cell-laden anti-inflammatory hydrogel enhances diabetic wound healing. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18104. doi: 10.1038/srep18104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrer RA, Saalbach A, Grunwedel M, Lohmann N, Forstreuter I, Saupe S, Wandel E, Simon JC, Franz S. Dermal fibroblasts promote alternative macrophage activation improving impaired wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:941–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng Y, Zheng S, Fan X, Li L, Xiao Y, Luo P, Liu Y, Wang L, Cui Z, He F, Liu Y, Xiao S, Xia Z. Amniotic epithelial cells accelerate diabetic wound healing by modulating inflammation and promoting neovascularization. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:1082076. doi: 10.1155/2018/1082076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Zallen JA. Wounded cells drive rapid epidermal repair in the early Drosophila embryo. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:3227–3237. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-05-0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stojadinovic O, Pastar I, Vukelic S, Mahoney MG, Brennan D, Krzyzanowska A, Golinko M, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Deregulation of keratinocyte differentiation and activation: a hallmark of venous ulcers. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:2675–2690. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang L, Di G, Qi X, Qu M, Wang Y, Duan H, Danielson P, Xie L, Zhou Q. Substance P promotes diabetic corneal epithelial wound healing through molecular mechanisms mediated via the neurokinin-1 receptor. Diabetes. 2014;63:4262–4274. doi: 10.2337/db14-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kant V, Kumar D, Kumar D, Prasad R, Gopal A, Pathak NN, Kumar P, Tandan SK. Topical application of substance P promotes wound healing in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Cytokine. 2015;73:144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costa R, Negrao R, Valente I, Castela A, Duarte D, Guardao L, Magalhaes PJ, Rodrigues JA, Guimaraes JT, Gomes P, Soares R. Xanthohumol modulates inflammation, oxidative stress, and angiogenesis in type 1 diabetic rat skin wound healing. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:2047–2053. doi: 10.1021/np4002898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eo H, Lee HJ, Lim Y. Ameliorative effect of dietary genistein on diabetes induced hyper-inflammation and oxidative stress during early stage of wound healing in alloxan induced diabetic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478:1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Senel O, Cetinkale O, Ozbay G, Ahcioglu F, Bulan R. Oxygen free radicals impair wound healing in ischemic rat skin. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39:516–523. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199711000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.