The COVID pandemic is a crisis that has significantly challenged patients, families, and healthcare workers. By enforcing strict isolation and no visitors, hospitals limited the spread of disease, but inadvertently wrought the devastation of patients dying alone. Many healthcare workers demonstrated great compassion, remaining at a patient’s bedside, helping to connect them with loved ones, and even holding their hands as they died. Intensive Care Units devised ways to limit potential contamination—confining patients behind sealed glass doors, keeping IV pumps and dialysis machines outside, and minimizing entry into rooms to only when absolutely essential—thereby increasing the isolation of the living. The significance of this separation on patients and on their loved ones has been widely recognized. But the toll and stress this extensive isolation and disconnect has had on providers has not been as well reported. In our practice, a relatively simple change not only made an impact on the families but also made a profound difference to everyone involved in the care of our patients.

Who are we—a cardiologist, an intensivist, a medical intern.

The cardiologist

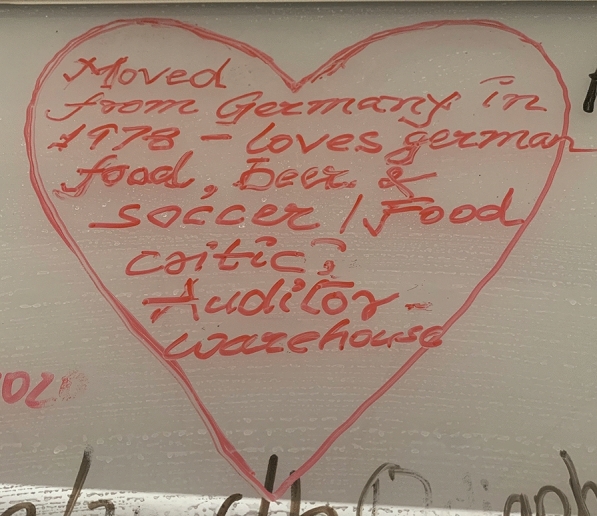

“I was deployed to a COVID ventilator care unit with patients recovering from severe respiratory failure. My patients were mostly sedated and unresponsive. The only means of getting to know them was from the report given by the overnight team at morning handover, and by thoroughly reviewing their electronic charts. Written on the opaque glass doors of my patients’ rooms was a dashboard of diagnoses, data, to-do lists and management plans. As I entered each room, I looked at the faces and wondered who they were and what lives they lived. Despite comprehensively managing their medical issues, I felt the need to know them, really know them. The next day, when I called the families, after giving updates on the patient’s condition, I asked the families to tell me something about their loved one, their likes and dislikes, what makes them “them”. I immediately heard a change in their voice and tone, from one of concern and distraught to one of love and hope. I could feel the warmth and tenderness as they described what this person meant to them, how much it hurt to not be next to them in their suffering, to not be able to hold their hand, to not be able to give them a hug. I spoke with a wife, a brother, a rabbi. It filled me with joy and compassion to hear what they had to say; I found the connection I was looking for. Later that evening, I overheard a nurse telling another nurse about what she read in my note, that her patient loves tennis and soccer, and how it brought tears to her eyes. The joy of connecting was evident in the hopeful voice of the family member, the connection I felt in my heart, and the soft tears in the nurse’s eyes. I added these little glimpses and personal characteristics to the opaque glass door so that their humanity could be shared with everyone taking care of them (Fig. 1).”

Fig. 1.

Picture of writings on the patient’s room door

The intensivist

“I had COVID early on. I knew the time course—when I was likely to be hospitalized, intubated, transferred to the ICU. By Easter Sunday, I figured I’d either be dead or have recovered.

I never got sick enough to be hospitalized. The Monday after Easter, I started my first stretch in a COVID ICU, taking care of 18–20 patients, all with complex multi-organ failure. On rounds, each patient seemed to blend into another. I told my team that I wanted them to learn and to present on rounds something unique about each patient. I hoped this would help me differentiate and remember 20 patients, and combat the inherent de-humanizing care this disease was forcing upon us—the isolation, the heavy sedation, the visitor restrictions. Surprisingly, instead of just going through the motions, my team embraced this request, and the details they gathered became a highlight of each presentation. Many of the anecdotes and stories in a city hospital are complex—a homeless woman who was a two-time cancer survivor and had a long history of mental illness; a deli worker who never missed a day of work, so when he missed 2 days, his boss went to his house and brought him to the hospital he trusts; a worker from abroad who regularly sends money back home to support his family; a prisoner on compassionate release. The difficult stories are no less humanizing, reminding us of our commitment to provide the same high level of care to all of our patients, no matter their background. We recognize that a patient’s social history is more than their use of alcohol or tobacco, their family history is more complex than just which ancestors died at what age of which diseases. The unique humanizing personal attributes are essential to collect, chart, and communicate. Not just during COVID, but always.”

The medical intern

“I had been working in a COVID ICU for five weeks; it completely changed how I practice medicine. Normally, along with the nurse, I spend more time with the patient and family than anyone else on the team. Now, no visitors were allowed. The patients all had the same devastating disease, severe COVID pneumonia. They required heavy sedation, high levels of ventilator and other support. I still updated the families every day, but it was the same script. “Your loved one is still in the hospital. They still need a lot of support. We don’t know how things will pan out. Unfortunately, you still can’t visit them.” These updates were met with gratitude, but left me feeling sad and perplexed.

At the start of my sixth week, my attending assigned the team an additional task of discovering an interesting fact about each of our patients to be presented on rounds. At first, I thought, “Oh no, another checkbox I need to tick off.” But I was pleasantly surprised, and this simple measure became a game changer. Instead of caring for intubated patients with COVID, I once again was taking care of people. My patient was a former carpenter, a husband of a healthcare worker; another was a long-distance runner who recently moved to the US and had never been sick before; another had a wife and special needs child who were praying that he would return home soon. They changed from being faceless victims of an invisible foe, to loved and cherished individuals.”

Families know that their loved one is a fighter, is the matriarch who kept everyone together, is the person who helped so many in their community and is needed to help so many more. By connecting with the families, asking them to talk about their loved ones, we are able to empathize with them, maybe make some of the difficult conversations a little easier, and help them understand that we care for their loved ones as individuals. We can relate to our patients in a more personal way, sometimes painfully for us as our own human vulnerability is exposed. As we work hard to get our patients to achieve medical goals like getting them off the ventilator, controlling their infection and helping them become strong again, we are able to get an insight into the lives our patients hope to return to. It reminds us why we do what we do. In our own difficult times during this crisis when we feel we cannot control the outcomes of all our patients, it gives us comfort to know that we provided care with love, respect, kindness and compassion. Ultimately, it is this human connection with our patients which is as essential to us as it is to our patients and their families.

Who are we? Healthcare workers, searching for humanity in the time of COVID, creating connections, healing together.

Authors’ contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.