Abstract

Background

Intimate Partner Violence is a “global pandemic”. Meanwhile, information and communication technologies (ICT), such as the internet, mobile phones, and smartphones, are spreading worldwide, including in low- and middle-income countries. We reviewed the available evidence on the use of ICT-based interventions to address intimate partner violence (IPV), evaluating the effectiveness, acceptability, and suitability of ICT for addressing different aspects of the problem (e.g., awareness, screening, prevention, treatment, mental health).

Methods

We conducted a systematic review, following PRISMA guidelines, using the following databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Key search terms included women, violence, domestic violence, intimate partner violence, information, communication technology, ICT, technology, email, mobile, phone, digital, ehealth, web, computer, online, and computerized. Only articles written in English were included.

Results

Twenty-five studies addressing screening and disclosure, IPV prevention, ICT suitability, support and women’s mental health were identified. The evidence reviewed suggests that ICT-based interventions were effective mainly in screening, disclosure, and prevention. However, there is a lack of homogeneity among the studies’ outcome measurements and the sample sizes, the control groups used (if any), the type of interventions, and the study recruitment space. Questions addressing safety, equity, and the unintended consequences of the use of ICT in IPV programming are virtually non-existent.

Conclusions

There is a clear need to develop women-centered ICT design when programming for IPV. Our study showed only one study that formally addressed software usability. The need for more research to address safety, equity, and the unintended consequences of the use of ICT in IPV programming is paramount. Studies addressing long term effects are also needed.

Keywords: Women, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), Information Communication Technology (ICT), Virtual communities, Public health

Background

Intimate partner violence includes physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological harm inflicted by a current or former partner or spouse [1]. Violence against women (VAW) has been described as a “global pandemic” by the United Nations [2]. It is considered both a violation of women’s human rights [3] and a public health issue [4]. In low- and middle-income countries, violence against women is widespread and often involves pregnant women [5, 6]. However, violence against women occurs in high-income countries as well [7, 8]. Nearly one in three women have experienced intimate partner violence or sexual violence [9]; therefore, it is important to disseminate as widely as possible the knowledge and tools related to IPV prevention and to intervention to empower the women subjected to IPV. Information and communication technologies (ICT) present an opportunity for such dissemination. ICT are being adopted at unprecedented rates in high-income as well as low- and middle-income countries [10]. Moreover, the use of the internet [11–37], mobile phones, and smartphones [36, 38–43] for health purposes has been well documented in research. It has been used to address chronic disease management [44, 45], mental health challenges [46, 47], and hospital readmissions [48], encompassing applications that target the public (i.e., public health informatics), interactions between patients and healthcare professionals, and applications for individual use through smartphone apps (i.e., consumer health informatics). However, little is known about the use of ICTs in the context of violence against women, and only a few articles on the subject have been published recently [43, 49, 50]. At the same time, there is a solid increase in phone ownership and access to the internet in low- and-middle-income countries [51], which suggests the possibility of implementing ICT-based interventions to address IPV in these countries.

Recent systematic reviews showed that the efficacy of ICT-based mobile apps for health (mHealth) is still limited, as research in the field lacks long-term studies and existing evidences of impact are inconsistent [52]. Also, mHealth in the domain of violence against women (VAW) showed an abundance of apps addressing one-time emergency or avoidance solutions, and a paucity of preventative apps, which indicates the need for studies addressing data security, personal safety, and efficacy of interventions using apps to address VAW [53]. By extension, investigating the situation of ICT in IPV seems a necessary step.

Given the existing IPV interventions challenges, the evidence demonstrating effectiveness of online interventions in health, the rise of research on online IPV interventions, the risks inherent in ICT use for IPV programming, it is important to synthesize the available evidence regarding the use of ICT-Based IPV interventions. To our knowledge, there is no systematic review of such work. To address this knowledge gap, we initiated a systematic review of literature on ICT-Based IPV interventions. The study objectives were to examine whether ICT could become acceptable for effective IPV interventions, we reviewed the literature on the use of ICT-based interventions to address IPV issues. The questions that guided us in examining the were as follows: (1) “what type of objectives did ICT based interventions tried to address?”, (2) “were ICT based interventions effective in addressing IPV?”, and (3) “what type of strategies did they implement to mitigate ICT risks (e.g. safety, data security)”. The results will inform future ICT-based IPV interventions.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted, employing a digital search of bibliographic databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. The literature was systematically screened by titles and abstracts and by applying key search terms. The following search terms were used: women, violence, domestic violence, intimate partner violence, information, communication technology, ICT, technology, email, mobile, phone, digital, ehealth, web, computer, online, and computerized. The full list of search terms is provided in Table 3 (See Appendix). Studies were included if they described an intervention that used some form of ICT, and if the recipients were women who experienced intimate partner violence or domestic violence, no matter what was the intervention type, comparison group, outcomes, study design, who was providing the intervention. We excluded studies that did not focus on ICT, studies where interventions were not aimed at women with IPV experiences, studies that described protocols, were not written in English, or were not full text, as well as journal articles and chapters in books. Non-English-language articles were excluded because no evidence exists of systematic bias caused by language restrictions [54]. The literature search was not subjected to any time limitations. The most recent search was completed on June 30, 2020.

The literature search, review, and data collection from articles was conducted by a single individual and was repeated by one other individual, the two resulting articles were then integrated. A meta-analysis was not conducted because of the disparities in study design, variables, and exposures between the studies.

Results

Summary

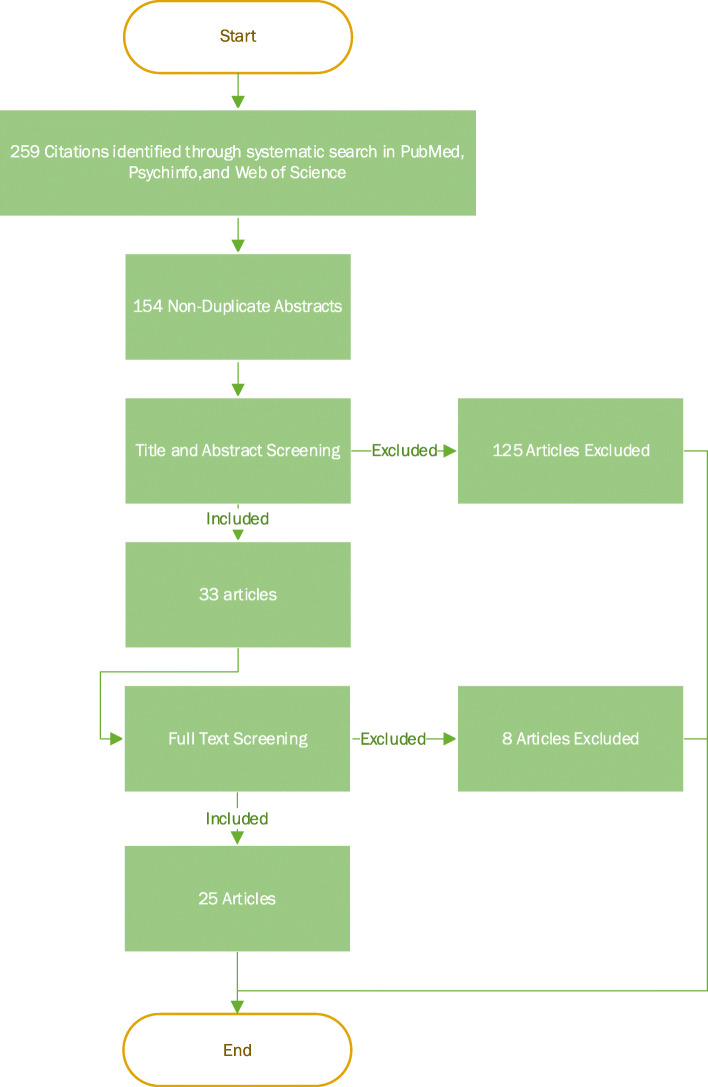

In total, 259 articles were identified, among which 105 articles were duplicates. Out of the 154 unique articles, 125 were excluded based on the content of their abstracts. The inclusion criteria were then applied to the remaining 33 articles after reading their full text. Four articles were then excluded, and 25 articles were kept for analysis [9, 55–78] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for article identification and selection

Table 4 (see Appendix) lays out the studies in terms of population, intervention, comparison groups, and outcomes (PICO). Table 1 presents the authors, publication year, study country, study type, recruitment space, theme, outcomes, sample size, sample size per arm, control group, and the type of ICT Used for the 25 studies. Out of the 25, 23 (92%) took place in North America (20 studies (80%) in the United States and 3 (12%) in Canada), 1 study (4%) took place in Australia, and 1 (4%) in New Zealand.

Table 1.

Summary of the 25 studies

| Author | Year | Country | Study Type | Recruitment Space | Theme | Outcomes | Sample Size | Sample Size per Arm | Control group | ICT Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmad. F [55]. | 2009 | Canada | RCT (2 arms) | Medical services | Screening and Disclosure | Count | 293 | 146.5 | Usual care (no online screening) | Desktop/Laptop |

| Bacchus. L.J. et al. [56] | 2016 | USA | Cross Sectional | Community wide | Screening and Disclosure | Count | 28 | 28 | Face-to-Face Paper based screening | Tablet |

| Braithwaite SR and Fincham FD [57] | 2014 | USA | RCT (2 arms) | Community wide | IPV Prevention | CTS2 | 52 | 26 | Static information and HomeWorks | Desktop/Laptop |

| Chang. J. C. et al. (2012) [58] | 2012 | USA | Pre-post | Medical services | Screening and Disclosure | NVQ | 50 | 50 | Same as Intervention Group; audio recorded their first visits to the provider | Desktop/Laptop |

| Choo E. K. et al. [59] | 2016 | USA | RCT (2 arms) | Social services | ICT Suitability | CSQ-8, SUS | 40 | 20 | Same website with an irrelevant content (fire safety) + phone booster | Tablet + Phone |

| Constantino. R. E. et al. [60] | 2015 | USA | RCT (3 arms) | Social services | Screening and Disclosure | IPVEQ, PRQ, ISEL, PROMIS | 32 | 11 |

Arm2: Face-to-face screening: same material Arm3: ARM #3 = Waitlist/Control |

Desktop/Laptop |

| Eden. K. B. et al. [61] | 2015 | USA | RCT (2 arms) | Community wide | Support, Decisional conflict | DCS, DA/DA-R | 708 | 354 | Standard safety planning online information + Resource website | Desktop/Laptop |

| Fincher D. (2015) [62] | 2015 | USA | RCT (2 arms) | Medical services | IPV Prevention | CTS2 | 368 | 184 | Face-to-face interview | Tablet |

| Fiorillo. D. et al. [63] | 2017 | USA | Pre-post | Medical services | Mental Health | LEC-5, SLESQ, DASS, PCL | 25 | 25 | Same as Intervention Group | Desktop/Laptop |

| Ford-Gilboe M et al. [64] | 2020 | Canada | RCT (2 arms) | Community wide | Mental Health | CESD-R, PCL-C | 531 | 265.5 | Static/Standard Non-tailored version of the same interactive website | Unknown |

| Gilbert. L. et al. [65] | 2016 | USA | RCT (3 arms) | Legal services | IPV Prevention | CTS2 | 306 | 102 |

Arm2: 4 Face-to-face traditional group sessions: same material Arm3: 4 weekly sessions for wellness promotion |

Desktop/Laptop |

| Glass. N., Eden.K. et al [66] | 2010 | USA | Pre-post | Social services | Support | DCS | 90 | 90 | Same as Intervention Group | Desktop/Laptop |

| Hassija C. and Gary MJ [67] | 2011 | USA | Pre-post | Medical services | Mental Health | PCL, CESD | 15 | 15 | Same as Intervention Group | Desktop/Laptop |

| Hegarty K et al. [68] | 2019 | Australia | RCT (2 arms) | Community wide | Support, Mental Health | GSE, CESD-R | 422 | 211 | Static intimate partner violence information | Unknown |

| Humphreys. J. et al. [69] | 2011 | USA | RCT (2 arms) | Medical services | Screening and Disclosure | Count, AAS | 50 | 25 | Usual care (no online screening) | Desktop/Laptop |

| Koziol-McLain. J. et al [9] | 2018 | New Zealand | RCT (2 arms) | Community wide | IPV Prevention | CESD-R, SVAWS | 412 | 206 | Static/Standard Non-individualized web-based information | Desktop/Laptop |

| MacMillan. H.L. et al. [70] | 2006 | Canada | RCT (3 arms) | Medical services | IPV Prevention | PVS, WAST, CAS | 2416 | 805 |

Arm2: Face-to-face interview Arm3: written self-completed questionnaire |

Desktop/Laptop |

| McNutt L. A.et al. [71] | 2005 | USA | RCT (3 arms) | Medical services | Screening and Disclosure | Count | 211 | 70 |

Arm2: Face-to-face screening with a nurse: same material (Short questionnaire) Arm3: Computer screening (Long questionnaire) |

Unknown |

| Renker, P. R., & Tonkin, P [72]. | 2007 | USA | Cross Sectional | Medical services | Screening and Disclosure | NVQ | 519 | 519 | No Control Group | Desktop/Laptop |

| Rhodes et al. [74] | 2002 | USA | RCT (2 arms) | Medical services |

Screening and Disclosure IPV Prevention |

PVS, AAS | 470 | 235 | Usual care (no online screening) | Desktop/Laptop |

| Rhodes. K.V. et al. [73] | 2006 | USA | RCT (2 arms) | Medical services |

Screening and Disclosure IPV Prevention |

PVS, AAS | 1281 | 640.5 | Usual care (no online screening) | Desktop/Laptop |

| Scribano et al. [75] | 2011 | USA | Prospective | Medical services | Screening and Disclosure | Count | 13,057 | 13,057 | Face-to-Face screening | Kisok |

| Sprecher. A. G. et al. [76] | 2004 | USA | Diagnostic Case-Control (AI) | Medical services | Screening and Disclosure | AI | 19,830 | 19,830 | No control group | Desktop/Laptop |

| Thomas. C.R. et al. [77] | 2005 | USA | Prospective | Social services | Mental Health | SCL-90-R | 35 | 35 | No control group | Desktop/Laptop and Telephone |

| Trautman. D. E. et al. [78] | 2007 | USA | RCT (2 arms) | Medical services | Screening and Disclosure | Count | 1005 | 502.5 | Usual care (no online screening) | Desktop/Laptop |

Most studies focused on women with potential vulnerability to, past experience of, and/or current experience of intimate partner violence, with the exception of one [74], which included both men and women as study participants. Four studies included women who were pregnant [56, 58, 69, 72]; two of these studies included women up to 3 months postpartum who had history of IPV [56, 72]. Two studies focused on women with a history of IPV and who were active substance(s) users [59, 65], and 1 study on women who were at risk of HIV through unprotected intercourse [65].

Out of the 25, 17 studies (68%) were solely desktop- or laptop-based [9, 55, 57, 58, 60, 61, 63, 65–67, 69, 70, 72–74, 76–78], 2 studies (8%) were solely tablet-based [56, 62], 1 study (4%) used computer and telephone [77], 1 study (4%) used tablet and telephone [59], 1 (4%) implemented a kiosk system [75] and 3 (12%) were not reported and supposed any type of ICT [64, 68, 71].

Studies’ designs and interventions

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the included studies. The 25 studies included 16 randomized controlled trials (12 two-arm and four three-arm studies), four pre-post designs, two cross-sectional studies, two prospective studies, and one diagnostic case-control study (i.e. retrospective data with known disease-positive and disease-negative cases [79]).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Characteristics | # of studies |

|---|---|

| (N = 25) | |

| Country: | |

| United states | 20 |

| Canada | 3 |

| a Other | 2 |

| Main focus | |

| Screening and Disclosure | 13 |

| IPV Prevention | 5 |

| Treatment (Mental Health) | 4 |

| Empowerment /Support | 2 |

| ICT Suitability | 1 |

| Recruitment Space | |

| Medical Services | 14 |

| Community wide | 6 |

| Social Services | 4 |

| Legal Services | 1 |

| Sample size: | |

| RCT (2 arms) | 40 to 1281 |

| RCT (3 arms) | 32 to 2416 |

| Pre-Post | 15 to 90 |

| Cross-Sectional | 28 to 519 |

| Prospective | 35 to 19,830 |

| Diagnostic Case-Control | 13,057 |

| Type of Study | |

| RCT (2 arms) | 12 |

| RCT (3 arms) | 4 |

| Pre-Post (one arm) | 4 |

| Cross-Sectional | 2 |

| Prospective | 2 |

| Diagnostic Case-Control | 1 |

| Study Settings | |

| Urban | 14 |

| Suburban | 2 |

| Mixed | 3 |

| Setting Not reported | 6 |

a Austria and New Zealand

Control groups varied widely, and wait-list controls were used in five RCT studies [55, 69, 73, 74, 78]. Four studies allowed control groups to access websites with static, or non-interactive, or non-tailored content [9, 57, 64, 68], while two studies used irrelevant information for control groups [59, 61], seven control groups used face-to-face (or paper-based self-reported) screening [56, 60, 62, 65, 70, 71, 75], four had the intervention group play the role of control (i.e. pre-post design) [58, 63, 66, 67], and three studies had no control groups [72, 76, 77]. The sample size in the RCT studies varied extensively from 32 participants to a high of 2416.

The 25 interventions implemented had various foci. ICT was used for screening and disclosure in 13 (52%) of the studies. Five studies (20%) aimed at IPV prevention, four (16%) studies used ICT to address the mental health of female victims of IPV, and two (8%) studies used ICT to provide support for decision aid. Only one (4%) study assessed mainly the suitability of ICT for use in an IPV context.

The 25 studies had five types of interventions and varied study settings. In terms of settings, 14 studies were conducted in medical services facilities [55, 58, 62, 63, 67, 69–76, 78] such as emergency departments, clinics, community health centers, trauma treatment centers, and family practices. Six studies were conducted in the community [9, 56, 57, 61, 64, 68], four in social services facilities [59, 60, 66, 77], and one in legal services facilities [65].

The 25 studies represent a range of uses of ICT in the context of IPV, addressing screening and disclosure, IPV prevention, ICT suitability, empowerment and support, and women’s health.

Screening and disclosure

In three studies, IPV screening using ICT was found to be as effective as using the usual face-to-face/paper method [58, 70, 71]. One study reported that computerized screening was more sensitive and less or similarly specific compared to face-to-face staff screening [71]. One study reported high self-disclosure of IPV using computers vs in person IPV screening with health professionals; out of 250 female patients who participated in both screening methods. 67(27%) patients out of the 250 disclosed some form of IPV in person compared to 85 (34%) who disclosed IPV via a computer. Out of those 85 patients, 60 (71%) also disclosed IPV to their doctors in person and 24 patients (26%) disclosed via a computerized tool but not with the doctor [58].

One study that included African American women in a women, infants, and children (WIC) services setting found that women were less likely to disclose IPV using a computerized intervention than in person [62]. A study that used a tablet for disclosure during perinatal home visitation found the tablet to be a conduit through which interpersonal connection between women and home visitors was facilitated [56]. One study found that women were more likely to disclose IPV using ICT, leading to higher rates of screening and disclosure [78]. One study reported that 81.8% of women disclosed using the ICT intervention, and only 16.7% women disclosed using usual care [69]. Another study found that implementing ICT-based disclosure in an emergency department was successful and reliable [75].

IPV prevention

Two studies addressed IPV prevention [57, 65]. One study showed that 62% of the participating women who used ICT were less likely to report experiencing physical IPV at a follow-up (12 months later), 76% were less likely to report IPV with injury, and 78% were less likely to report severe sexual IPV [65]. The study by Braithwaite et al., which targeted both males and females using ICT, reported less physical aggression committed by females at post-intervention, as well as less physical aggression committed by both males and females at a 1-year follow up; also, the study showed a large reduction in expected counts for female- and male-perpetrated physical aggression at the 1-year follow-up (71 and 99%, respectively) [57].

Women’s health

Our systematic review showed that ICT has been used to address two aspects in the lives of some women experiencing IPV: substance use and mental health. Six studies used online tools to address the mental health of women experiencing IPV [9, 55, 60, 63, 67, 77]. Depression was measured in five studies [9, 55, 60, 63, 67], anxiety was measured in three [60, 63, 77] and stress in two [63, 67, 77]. In all studies, mental health showed improvement compared to intervention. One study reported that women found it easier and safer to report drug use and partner abuse through a computer than in person [77]. The study by Hassija et al. addressed the treatment of IPV-related trauma through video conferencing, and found the method effective at reducing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, with high users’ satisfaction [67].

Empowerment and support

ICT was used to empower women by enabling them to create safety and action plans and by providing them with tools for enhanced decision making and self-efficacy. Three studies focused on women creating a safety and/or action plan in the event of a future partner abuse incident [61, 66, 69], with two interventions providing additional local resources [61, 69]. In one study, 90% of the participating women who used ICT reported leaving their abusive partner within the year [66], and in another study 64% of the participating women reported the intention to make changes in regard to their IPV within 30 days to 6 months [69]. Moreover, in a single study focused on using online tools to teach participants about behaviours and/or actions related to safety [9], researchers reported a 12% significant increase in safety behaviours for the ICT-based intervention group, compared to a 9% increase for the control waitlist [9]. In addition, a study reported that participants found using a computer survey to disclose IPV safer than a face-to-face survey [55].

In terms of decision-making and self-efficacy, two studies reported that more than 78% of the participants acquired general skills through the ICT-based interventions [9], and two other studies reported that participants gained decision-making skills through the ICT-based interventions [61, 66]. Additionally, using their new skills, women experienced lower decisional conflicts and had an overall less difficult time deciding on their actions [61, 66].

ICT suitability

Only 1 study has a formal testing for the usability of ICT software as a major focus using the Systems Usability Scale [59]. The results indicate high satisfaction with the software usability.

Measurements

Table 5 (Appendix) summarizes the outcomes measured by each study. Our review revealed a wide variation among studies in terms of outcomes measured for studies that address the same focus. In total, 27 measurement tools were used in the 25 studies (see Table 5 in Appendix).

Among the 12 studies that address screening and disclosure, five studies used a simple disclosure count [55, 56, 69, 75, 78]. Two studies used non-validated questionnaires [58, 72], and two studies used the Partner Violence Screen (PVS) and the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS) [73, 74]. Three studies had no common outcome measurement tools.

The four studies [63, 64, 67, 77] that focus on mental health used eight different outcome measurement tools; only the PTSD Checklist (PCL) was common to two studies [63, 67].

In terms of suitability of ICT, the Systems Usability Scale (SUS) was used in one study only to assess software usability [59].

Out of the five studies [9, 57, 62, 65, 70] focusing on IPV prevention, three studies [57, 62, 65] used the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2). The two studies that addressed support [66, 68] had no common measurement tools.

Discussion

Principal findings

Our review revealed the emerging nature of ICT use in IPV research. While there is a growing interest in the use of ICT in IPV interventions, there are virtually no studies examining its challenges.

While most of the studies used ICT to enhance screening and increase the disclosure rate, few studies targeted IPV prevention and even fewer aimed at improving support. Suitability of ICT was seldom assessed in a formal way using a validated usability scale (e.g. Systems Usability Scale) or methodology [80].

In addition, while most of the studies used RCT design, the number of arms, the population, the control groups used, the sample sizes, and the outcome measures varied widely among the studies, which makes it hard to compare those results. With the exception of two large sample sizes that were used in two non-RCT studies (one that accessed electronic health records for an artificial intelligence application [76], and another that used the emergency department [75]), the sample sizes per arm were generally low. The sample size per arm was less than 30 in four studies. Only six studies had a sample size per arm between 100 and 300, and only four studies had a sample size per arm between 300 and 805. This suggests that the current ICT-based IPV interventions have limited generalizability and comparability—especially because only six studies were conducted in the community.

Twenty-three (92%) of the studies were conducted in North America, 20 (80%) of which were in the United States, which is an additional limitation to the generalizability of the findings since they lack diversity in terms of ethnicity, race, language, and cultural backgrounds. Diversity is crucial in IPV. Research shows that foreign-born immigrant as well as indigenous women are more likely to experience IPV [81, 82] and intimate partner homicide than other women [83, 84]; hence, addressing diversity in IPV is critical. It is encouraging that one recently published RCT protocol laid out a plan for culturally tailored intervention targeting immigrant, refugee, and indigenous survivors of IPV [85].

Equity

Technology is costly in terms of hardware, software and data plan costs. Consequently, while access to ICT by women experiencing IPV is a challenge in high income countries, including the United States [86, 87], it is even more difficult in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This creates inequity in access to technology, and a digital divide among women subject to IPV. This inequity challenge and its impact on outcomes has long been observed in electronic health (eHealth) [88, 89] and needs to be addressed in ICT-based IPV interventions; it was not addressed in the studies covered by our review. Also, involvement of users in software design is a well-known need that is effective in producing software that works for users and aligns with their priorities and is suitable for their environments [47, 90–94]. Hence, involving women experiencing IPV in the research team and in the ICT software design process is paramount to ensure usability and accessibility of the software and as a matter of equity [95]. There is a lack of research in this area in the studies covered by our review.

A recent study protocol is promising that ICT will ensure lower access barriers [96], which is the traditional unchecked point of view; this is another demonstration of the need to shed a critical light on the use of ICT for women experiencing IPV, analyzing equity as well as the safety and ethical challenges involved.

Safety and ethical challenges

Our review shows that 8 studies [55, 56, 59, 63, 64, 70, 72, 75] reported that women found ICT interventions suitable for IPV disclosure; three of those studies found it particularly suitable in terms of confidentiality, usefulness, and satisfaction [56, 63, 72]. Stigma is an important factor associated with intimate partner violence [97] limiting agency in help-seeking for IPV [98]; ICT seems to be a tool that provide an opportunity for women subject to IPV. With the exception of one in which participants preferred a face-to-face discussion [62], IPV disclosure through ICT was found to be most appropriate in most of the studies compared to face-to-face disclosure and was perceived as non-judgemental and more anonymous than face-to-face discussion, which facilitated more disclosure.

The increase in phone ownership and internet access in low- and middle-income countries [51], coupled with the ability to use ICT to target individuals through health informatics tools that targets individuals (i.e. consumer health informatics) [99] such as apps, makes ICT a flexible tool to address IPV in multiple languages, embedding different cultural cues, and overcoming the cultural stigma related to disclosing IPV from the convenience of a personal ICT device (e.g. cell phone, smart phone). Simple ICT tools such as cell phones are available in rural areas and proved to be successful tools in the health domain (e.g. chronic disease management) [100–102]. However, it is important to note that one challenge of ICT-based interventions is that only women with basic literacy and IT knowledge can benefit; also, some victims may not have access to ICT, and some abusers may restrict their partners’ access to ICT. Therefore, in addition to the traditional security considerations related to the use of ICT, such as maintenance of privacy [103] and confidentiality [99], there are ethical issues related to the unintended consequences of ICT [104, 105], including safety risks.

In the IPV domain, sharing cell/smart phones at home or with neighbors is a common practice [106, 107], which might increase the risk of IPV if the perpetrators notice that women are using these devices to address IPV [108]. The studies covered by this review were located in high income countries; there is little to no examination of the problem of access to ICT (i.e. cost), nor of the risks inherent in the use of ICT (e.g. sharing devices, ability to access browsing history) in addressing IPV programming in a variety of contexts. Ethical challenges related to the safety of women increase when women are sharing cell/smart phones with perpetrators; in such contexts special considerations should be taken care of, including “safety by design” [109].

Safety challenges involved in the use of ICT in health have recently attracted much attention [105, 110]. Moreover, recent reflections related to the ethical challenges of using web-based RCT show the need to equip participants with information about Internet safety [111]; likewise, identifying and managing safety risks within ICT-based IPV research remains a perspective to be explored. This raises ethical questions related to the use of ICT, for example in the case of referral embedded in the IPV programming, as was the case in three studies included in this review [55, 73, 78]. Poor quality services are well documented in low-resource and rural areas [112], so referring women to such services might have negative consequences for them. While this is not an ICT issue, ICT facilitates communication of information and has the potential to exacerbate current challenges. This is part of the well-known unintended consequences of the use of information technology in health [113–115].

Future directions

Of the 19 studies that explicitly mentioned their settings, 14 were in urban settings, only three were in urban and suburban areas, and two were in suburban settings, suggesting a need to test ICT use for IPV in rural settings [67, 77] and uncover any particularities compared to the urban context.

It is also worth noting that our systematic review has not included search terms regarding the user of ICT tools to address IPV for women with disabilities. However, in a quick assessment, when we searched in PubMed for research that addresses the use of ICT to address violence in the context of women with disabilities, our search revealed only two papers [116, 117]. The use of ICT to address IPV for this particular group of women is important to address in a separate study, as ICT accessibility may be challenging for women with certain types of disabilities, especially since there is evidence that IPV occurs at higher rates in this population compared to the general population [118–123], and that ICT can play a major role in empowering people with disabilities [124]. The use of ICT tools to address IPV for women with disabilities, and the accessibility of these tools, remains an important area for future studies.

Moreover, our review indicated that there is a paucity of research addressing ICT use for IPV prevention and IPV treatment. There is a clear need for more research on ICT-based interventions to prevent IPV and to address post-IPV challenges, such as mental illness and the integration and coordination of mental and social services (e.g., employment, housing), which has never been addressed in the reviewed literature. In this context, virtual communities may play an important role in integrating and coordinating mental health services and social services [125]. While the studies showed different aspects of ICT use for IPV, a more integrative approach can be taken if researchers approach IPV using a virtual community framework. A virtual community (VC) is defined as a community of individuals cooperating using online tools to attain an objective [126]. Health VCs have been used in healthcare to provide patients with education, health education, and remote support; that proved to be an enabling and empowering factor, which allowed patients to become active participants in managing their health conditions [127, 128]. Support was not provided solely by health professionals; instead, health VCs connected individuals with common experiences (e.g., similar health conditions), which enabled them to interact and mutually support each other [129]. Healthcare providers could provide validated evidence-based health information, coupled with strategies for effective chronic disease management [130–132]. Ample evidence exists demonstrating that virtual tools are effective and efficient for addressing health issues experienced by patients with various health conditions (chronic kidney disease, pulmonary hypertension, cancer) [126, 132–134]. There is also ample evidence that health VCs are effective in engaging individuals managing their own health condition [131, 132]. Moreover, VCs can be patient-centred, customizable to individual preferences, and responsive to individuals’ needs and values [135]. In terms of mental health, an important factor for women experiencing IPV, VCs provide a secure, private way for women to communicate privately and securely and to access information tailored to their situation in a personalized manner. This privacy facilitates access and assists in overcoming stigma, especially for women from visible minority groups [136]. VCs have a proven potential to engage participants [137]. There is ample evidence that health VCs are associated with positive mental and social benefits, such as reduced loneliness and increased emotional well-being, self-esteem, and self-empowerment [129, 138, 139]. It is important to explore an integrative approach to ICT-based intervention in IPV using VCs, especially since VCs enable a community dimension that facilitates mutual support and empowerment among its members (e.g., abused women).

ICT vs. paper

In a study that screened for IPV, while women preferred computerized over face-to-face disclosure, computerized screening did not increase prevalence, so ICT did not lead to increase in disclosure. Also, when women disclosed by answering paper-based questionnaires, the self-completed paper-based questionnaires had less missing data collected than both computer-based and face-to-face interviews [70], which shows the advantage of having for paper-based screening (i.e. less missing data).

Likewise, while ICT allowed considerably higher IPV detection, this did not always lead to charting for IPV or to a follow-up by treating physicians [74]; more research is needed to understand the factors, such as continuing medical education [140], that increase the chances of charting and follow-up. Detection is not enough.

We have noted above the lack of research regarding equity, safety, and the ethical challenges involved in the use of ICT, as well as the lack of culturally, ethically, and racially sensitive ICT programs. ICT might be able to support and enhance more traditional on-the-ground program delivery; however, ensuring that effective ICT-based interventions reach the most vulnerable in equitable, ethical, and safe ways remains a research agenda to be undertaken.

Current results suggest that face-to-face and paper-based approaches should not be discarded, and that the computer-based software design must be user-centred and must follow usability principles [141, 142].

Limitations

Limiting the search to English language is one of the limitations of this study. Another limitation was the difficulty to compare the results, since the tools used to measure the same outcome varied widely between the studies. Various questionnaires were used to detect IPV, assess decisional conflict, assess mental health challenges, assess treatment efficacy, and assess different primary and secondary outcomes. An illustrative example is the varied questionnaires that researchers used to measure IPV [55, 57, 60, 62, 65, 69, 73–75], which included the use of an artificial neural network to identify IPV automatically via analysis of the notes stored in the electronic health records [76]. Our review shows that there are limits for comparing the effectiveness of the interventions in terms of mental health (e.g., reduction in stress, anxiety, or depression levels), given the great variety of mental-health-related measurement tools that have been used.

Conclusion

The evidence reviewed suggests that ICT-based interventions have the potential to be effective in spreading awareness about and screening for IPV. ICT use show promise for reducing decisional conflict, improving knowledge and risk assessments, and motivating women to disclose, discuss, and leave their abusive relationships. However, there is lack of homogeneity among the studies’ outcome measurements, and the sample sizes, the control groups used (if any), the type of interventions and the study recruitment space.

The use of ICT-based interventions seems to be an attractive option for disseminating awareness and prevention information [143], due to the wide availability of ICT (including simple mobile phones) in both high-income and low- and middle-income countries. ICT may also present an opportunity to deliver culturally sensitive multilingual interventions using consumer health informatics. However, there is a clear need to develop women-centred ICT design when programming for IPV. Our study showed only one study that formally addressed software usability. Moreover, research directly addressing safety, equity, and ethical challenges in using ICT in IPV programming are virtually non-existent; the need to find answers to equity, and the unintended consequences of the use of ICT use for IPV programming is necessary. In this context, virtual communities may play an important role in providing a sense of community and in integrating and coordinating the services around women experiencing IPV. Future longitudinal follow-ups could help determine the long-term effects of the use of ICT in IPV programming.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of Kanchi Uttamchandani in searching for some of the articles.

Abbreviations

- IPV

Intimate Partner Violence

- ICT

Information and Communication Technologies

Appendix

Table 3.

Search Terms

| PubMed | |

| 1 | (((women[Title]) AND violence[Title])) AND English[Language] |

| 2 | ((domestic[Title]) AND violence[Title]) AND English[Language] |

| 3 | (Intimate Partner Violence[Title]) OR IPV[Title] AND English[Language] |

| 4 | ((information and communication technology[Title]) OR ICT[Title] OR technology[Title] OR email[Title] OR mobile[Title] OR phone[Title] OR digital[Title] OR ehealth[Title] OR web[Title] OR computer[Title] OR online[Title] OR computerized[Title]) AND English[Language] |

| (1 OR 2 OR 3) AND 4 | |

| PsycINFO | |

| 1 | ti(women) AND ti(violence) AND la.exact(“English”) |

| 2 | ti(Domestic Violence) AND la.exact(“English”) |

| 3 | ti(Intimate Partner Violence) OR ti(IPV) AND la.exact(“English”) |

| 4 | (ti(information AND communication technology) OR ti(ict) OR ti(technology) OR ti(email) OR ti(mobile) OR ti(phone) OR ti(digital) OR ti(ehealth) OR ti(web) OR ti(computer) OR ti(online) OR ti(computerized) AND la.exact(“English”)) |

| 5 | (1 OR 2 OR 3) AND 4 |

| Web of Science | |

| 1 | (ti = (women) AND ti = (violence)) AND LANGUAGE:(English) |

| 2 | (ti = (Domestic Violence)) AND LANGUAGE: (English) |

| 3 | (TI = (Intimate partner Violence OR IPV)) AND LANGUAGE: (English) |

| 4 | (TI = (information communication technology) OR TI = (ict) OR TI = (technology) OR TI = (email) OR TI = (mobile) OR TI = (phone) OR TI = (digital) OR TI = (ehealth) OR TI = (web) OR TI = (computer) OR TI = (online) OR TI = (computerized)) AND LANGUAGE: (English) |

| (#1 OR #2 OR #3) AND #4 | |

Table 4.

PICO table

| Author, Year | Population | Intervention (Study Design, Perspective, Time Horizon) | Comparison Group | Outcome (Results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmad. F., et al. (2009) [55]. |

Female patients -at least 18 years of age, -in a current or recent intimate relationship (within the last 12 months), -were able to read and write English Setting: Family practice clinic in an urban Hospital N = 293 women |

Intervention Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: usual care + computer survey Duration: 7 months (March–September 2005) Follow-up: NA Intervention group: 144 Primary Outcome -Initiation of discussion about risk for IPVC (discussion opportunity) -detection of women at risk based on review of audiotaped medical visits. Secondary outcomes provider assessment of patient safety provision of appropriate referrals and advice for follow-up patient acceptance of the computerized screening Measurement Tools IPVC questions from: Abuse Assessment Screen, Partner Violence Screen, items from Improving Health Care Response to Domestic Violence: A Resource Manual For Health Care Providers Depression questions Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Geriatric Depression Scale Computer Acceptance acceptance of computer-assisted screening by using the Computerized Lifestyle Assessment Scale (CLAS) |

Control group: 149 Usual care |

Attrition: 7% Primary outcomes -Computer screening was associated with statistically significantly more opportunities for discussing and detecting mental health disorders -Opportunity to discuss IPVC arose for 35% (48/139) in the computer-screened group and 24% (34/141) of the usual care group -Detection of IPVC occurred in 18% (25/139) of the computer-screened group and 9% (12/141) of the usual care group Secondary outcomes - provider assessment of patient safety: In IPVC positive detections, Physicians assessed patient safety more often in the computer-screened group: 9 of 25 participants in intervention vs 1 of 12 participants usual care group- Provision of appropriate referrals and advice for follow-up: 3 patients in the computer-screened group and 1 in the usual care group received referrals. During these visits, physicians asked patients to set up a follow-up appointment more often in the computer-screened group (20 of 25 participants) than in the usual care group (8 of 12 participants). - Patient acceptance of the computerized screening: Participants agreed that screening was beneficial but had some concerns about privacy and interference with physician interactions |

| Bacchus. L.J. et al. (2016) [56]. |

women aged 25 to 66 years pregnant or up to 3 months postpartum with prior IPV Setting: women enrolled in a US-based randomized controlled trial of the DOVE intervention N = 26 Women Interviewed (18 IPV positive) |

Intervention Type: Cross Sectional (interviews) Intervention Group: 8 Intervention: tablet application Visitation Program (DOVE) to disclose IPV Intervention Group: 8 women (8 IPV positive and 1 IPV-negative) used the DOVE tablet application |

Home Visitor paper-based Method N = 18 (11 IPV positive and 7 IPV negative) |

−18 women were IPV positive - mixed feeling about the DOVE program (impediment vs facilitator) -patient-provider relationship is paramount - mHealth should be considered as a supplement and enhance therapeutic relationship - mHealth should be flexible and adapt to changing patient context |

| Braithwaite SR and Fincham FD (2014) [57] |

Married Couples Setting: community 52 couples (N = 104) |

Study Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: presentation, online videos, weekly home assignments, emails Duration: 6 weeks Follow-up: 1 year Intervention Group: 25 Outcome IPV: measure by Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2). |

Active Control Group: 26 Presentation and inert information and HomeWorks |

Self-reported Physical aggression receiving ePREP was associated with -less female-perpetrated physical aggression at post-treatment - less male-perpetrated physical aggression at 1-year follow up - and less female-perpetrated physical aggression at 1-year follow up - 71% reduction in expected counts for female-perpetrated physical aggression and a 99% reduction in expected counts of male perpetrated physical aggression at the 1-year follow-up Partner-reported physical aggression receiving ePREP was associated with - an increase in female-perpetrated physical aggression at post-treatment - significant decreases in female perpetrated physical aggression at the 1 year follow-up - 97% reduction in expected counts of physical aggression Self-reported psychological-aggression receiving ePREP was associated with a significant reduction in self-reported male-perpetrated psychological-aggression at the 1 year follow-up Gains were maintained at a 1-year follow-up assessment |

| Chang. J. C. et al. (2012) [58] |

Women ages 18 years or older Pregnant English-speaking Coming for first OB/GYN visit Setting: hospital-based prenatal clinic N = 250 patient (for 50 providers) |

Intervention Type: cross-sectional Survey Intervention: Computerized non-validated questionnaire Duration: NA Follow-up: 4 weeks after survey (Semi-structured interviews with those who reported experiencing IPV) Intervention group: 250 patients |

Control group: Same as Intervention Group; audio recorded their first visits to the provider Control Size: 302 participants |

Out of 250 women - 34% disclosed any type of IPV via computer - 27% disclosed any type of IPV in person - Out of 85 women who disclosed IPV via computer -71% disclosed also in person -Out of 91 women who disclosed with either computer or in person -36% disclosed via the computerized tool but did not disclose in person -7% disclosed IPV in person to the provider but not on the computer - According to patient feedback, the use of both FTF and Computerized should be used together |

| Choo E. K. et al. (2016) [59] |

women aged 18 to 59 reporting both drug use and IPV Setting: Emergency Department N = 40 women in total |

Study Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: Tablet based education modules for IPV (B-SAFER) with content on drug use and IPV + phone booster Duration: one session for the web component; 2-weeks for the Booster Follow-up: NA Intervention group: 21 women Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: Primary Satisfaction Outcomes 8-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; 10-item Systems Usability Scale (SUS) |

Control group: 19 B-SAFER (with a content of fire safety) + phone booster |

Mean usability score (SUS): 83.5 (95% CI 78.1–88.9) out of a possible 100. Mean overall satisfaction score (CSQ-8) was 27.7 (95% CI 26.3–29.1) out of a possible 32. |

| Constantino. R. E. et al. (2015) [60] |

Women -ages 18 or older -English-speaking -Have basic literacy skills -Not living with perpetrator -Has experienced IPV in past 18 months Setting: Neighborhood Legal Services Association; Family Court waiting area; A Women’s Center and Shelter N = 32 women |

Intervention Type: RCT (3 arms) Intervention: ONLINE-HELLP modules via email or face-to-face per week Duration: 6 weeks (once a week) Follow-up: NA Intervention group:11 women Primary Outcomes and Measurement Tools -IPV Experience Questionnaire (IPVEQ), -Availability of personal support: Personal Resource Questionnaire (PRQ) -Perceived availability of interpersonal and community support: Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) -Anxiety, anger and depression: The PROMIS version 1.0 short form |

ARM #2 = 6 FTF-HELLP modules in person (face-to-face) Size:10 women ARM #3 = Waitlist/Control group: no intervention Size: 11women |

•At baseline, (62%) reported being in physical pain due to IPV •Anxiety, depression, ISEL all showed significant improvements |

| Eden. K. B. et al. (2015) [61]. |

women aged 18 years or older English-speaking previous history of IPV Setting: women in the general community in 4 states N = 708 women |

Intervention Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: IRIS Online Interactive safety decision aid with personalized safety plan Duration: One use Follow-up: NA Intervention Group: 354 Primary Outcome and Measurement Tools: Decisional conflict: Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS) |

Control group: 543 Online Usual safety planning Resource website |

• After just one online session: intervention women had significantly lower total decisional conflict than control • no statistically significant difference between control and intervention groups on changes in feeling uninformed |

| Fincher D. (2015) [62] |

Low-income African American Women receiving Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) − 18 years old, -eligible to receive WIC services, -English speaking, -literate Setting: Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) N = 368 |

Study Type: RCT 2-arm Intervention: via computer-assisted self interview (CASI) Duration: 2 months (July 17, 2012, and September 21, 2012) Follow-up: 2 weeks (ask about experience with and preference of screening method) Intervention Group: 117 (computed as 48.1% of N) Primary Outcome and Measurement Tools: general health behaviors, tobacco use, alcohol use: TWEAK: Tolerance, Worried, Eyeopener, Amnesia, Cut down substance use (Drug Abuse Screening Test IPV victimization: Revised Conflict Tactics Scales–Short Form (CTS2S) 12 dichotomous (yes, no) outcomes for -disclosure of lifetime and prior-year: (a) negotiation skills, (b) exposure to psychological IPV, (c) exposure to physical IPV, (d) exposure to sexual IPV, (e) exposure to any IPV (psychological, physical, or sexual), (f) IPV related injury |

Control group: 251 (computed as N-117) face-to-face interview (FTFI). |

Women screened via FTFI reported significantly more lifetime and prior year negotiation and more prior year verbal, sexual, and any IPV than CASI-screened women 117 women completed follow-up (3.8% of sample) Face-to-Face more effective for IPV disclosure |

| Fiorillo. D. et al. (2017) [63]. |

-women ages 18 years or older -fluent in English -experience of trauma in the form of sexual or physical abuse -have high level of psychological distress (score of 4+ on the binary version of the 12-item General Health Questionnaire) Setting: local mental health and community agencies N = 25 |

Intervention Type: Open trial, without control and randomization Intervention: web-based ACT (acceptance and Commitment Therapy) focused specifically for treatment of PTSD in survivors of interpersonal trauma Duration: 6 weeks (6 sessions) Follow-up: NA Intervention Group: 25 women Primary Outcomes and Measurement Tools: exposure to trauma: Life Events Checklist (LEC-5); Distress: General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire (SLESQ) PTSD Checklist (PCL-5) Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) Secondary Outcomes and Measurement Tools: Knowledge of ACT (ACT Knowledge Quest) psychological flexibility (Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II)) |

Control Group: Same as Intervention Group |

• Attrition: 16% (84% completed the treatment and post-treatment assessments) • Significant improvements in targeted outcomes (PTSD, depression, anxiety) upon completion of the 6-session web-based intervention better ACT knowledge and psychological flexibility |

| Ford-Gilboe M et al. (2020) [64] |

Women, 19 years or older who experienced IPV in the previous 6 months. Setting: community settings (e.g. libraries) N = 531 women |

Study Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: tailored, interactive online safety and health intervention Duration: 12 months Follow-up: 3, 6, 12 months Intervention group: n = 267 women Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: Primary: depressive symptoms (CESD-R) and PTSD symptoms (PCL-C) Secondary: helpfulness of safety actions, confidence in safety planning, mastery, social support, experiences of coercive control, and decisional conflict |

Control Group: n = 264 non-tailored version of the interactive online safety and health intervention |

Both groups improved on depression and on all secondary outcomes The tailored intervention had greater positive effects for women (1) with children under 18 living at home; (2)reporting more severe violence; (3)living in medium-sized and large urban centers; (4)and not living with a partner |

| Gilbert. L. et al. (2016) [65]. |

women aged 18 years or older Substance-abusers Have at least 1 HIV risk factor Engage in unprotected intercourse Setting: multiple community corrections sites N = 306 women |

Intervention Type: RCT (3 arms) Intervention: 4 group sessions with computerized WORTH, self-paced IPV prevention modules Duration: 1 week Follow-up: 6 months, and 12-months Intervention group:103 women Primary Outcome and Measurements Tools: the risk of different types of IPV victimization: 8-item version of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale Secondary Outcome and Measurements Tools Illicit drugs ever and within the past 90 days.: Risk Behavior Assessment |

ARM 2: 4 weekly traditional group sessions covering same material without computersSize:101 womenControl group/ARM 3: 4 weekly sessions for wellness promotion Size: 102 women |

-Computerized WORTH participants were 62% less likely to report experiencing any physical IPV at the 12-month follow-up; 76% less likely to report injurious IPV; 78% less likely to report severe sexual IPV No difference was observed between computerized WORTH and traditional WORTH |

| Glass. N., Eden.K. et al. (2010) [66] |

Participants Female Patients who Spoke English or Spanish 18 years of age or older reported physical and/or sexual violence within a relationship in the previous year Setting: domestic violence shelters or domestic violence support groups N = 90 women |

Intervention Type: Open trial, without control and randomization Intervention: Computerized safety decision aid Duration: NA Follow-up: NA Intervention Group: 90 (Age 17 to 63) Primary Outcomes and Measurement Tools The Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS) Feeling Supported Certainty about safety plans Knowledge of options Clear Priorities Other tools -Danger Assessment (DA) |

Control group: Same as Intervention Group Control Size:90 participants |

-Mean DA at baseline was (18.14), meaning extreme danger during the last year -Post intervention statistically significant measures - participants felt more supported in their decision - reported less total decisional conflict - No significant difference - Certainty about their safety plans - Knowledge of their options - Clear Values/priorities − 60% reported having made a safety plan − 76% included a plan to leave the relationship limitations: - participants were already in a help seeking phase (shelter, support groups) - More than 90% of these participants reported they had left the abusive relationship in the past year |

| Hassija C. and Gary MJ (2011) [67] |

Age 19–52 referred to from a distal domestic violence and rape crisis centers Setting: Trauma Telehealth Treatment Clinic N = 15 |

Study Type: Open trial, without control and randomization Intervention: Treatment via videoconferencing Duration: mostly are one-time consult Follow-up: NA Primary Outcomes and Measurement Tools -PTSD severity: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL) - DSM IV -Depression symptom severity: The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), -Client satisfaction: Wyoming Telehealth Trauma Clinic Client Satisfaction Scale (WTICCSS) |

Control Group: Same as Intervention Group |

Large reductions on measures of PTSD and depression symptom severity High degree of satisfaction |

| Hegarty K et al. (2019) [68] |

Women, 16–50 years who had screened positive for any form of IPV or fear of a partner in the 6 months before recruitment. Setting: community settings N = 422 women |

Study Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: I-DECIDE: Website on healthy relationships, abuse and safety, and relationship priority setting, and a tailored action plan. Duration: 3–60 min Follow-up: 6 months, 12 monthsIntervention group: n = 227 women Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: - Self-efficacy (Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale) - depression (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale—Revised) |

Control Group: n = 195 Static intimate partner violence information (5 min duration) |

Women in the control group had higher self-efficacy scores at 6 months and 12 months than did women in the intervention group No between group differences in depression at 6 months or 12 months Qualitative: Qualitative findings indicated that participants found the intervention supportive and a motivation for action. |

| Humphreys. J. et al. (2011) [69] |

Pregnant women who presented for routine prenatal care who also reported being at risk for intimate partner violence (IPV) English-speaking 18 years or older Fewer than 26 weeks pregnant Receiving prenatal care at one of the participating clinics, Not presenting for their first prenatal visit Setting: prenatal clinics Urban N = 50 |

Intervention Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: Video Doctor that generates: Provider Cueing + patient education sheet Duration: NA Follow-up: 1 month during next monthly routine visits Intervention Group: 25 Outcomes and Measurements Tools - IPV: Abuse Assessment Screen -occurrence of patient–provider discussion of IPV risk: Abuse Assessment Screen-participants’ perceived helpfulness of the discussion. -intention to make changes: seriously thinking of making a change within next 30 days or 6 months |

Control group: N = 25 usual prenatal care |

Video Doctor plus Provider Cueing significantly increases health care provider–patient IPV discussion -At baseline: 81.8% of Intervention group participants reported IPV vs. 16.7% control group (significant) -At 1-month follow-up: 70.0% of Intervention group participants reported IPV vs. 23.5% control group (significant) - 90% of intervention participants were significantly more likely to have IPV risk discussion with their providers at one or both visits compared 23.6% of control group participants who received usual care - 32 participants reported the intention to make changes regarding IPV within the 30 days to 6 Months vs. 14 participants in control |

| Koziol-McLain. J. et al. (2018) [9]. |

women experience IPV in the last 6 months; aged 16 years or older; have access to safe: computer, email address, and internet Setting: online Ads (info from previous publication) N = 412 women total Note: 27% Maori(indigenous) |

Intervention Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: Web-based decision aid (i-safe -individualized website) who experienced IPV during the last 6 months Duration: 12 months (September 2012 to September 2014) Follow-up: 3,6, and 12 months Intervention Group = 202 Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: CESD-R: self-reported mental health (depression) SVAWS: Severity of Violence Against Women Scale |

standardized, non-individualized web-based information Control Group = 210 women |

-Attrition: 35% -individualized Web-based isafe decision aid -Intervention group had 12% increase in safety behaviors, control group had 9% increase − 78% stated isafe provided them with new skills − 91% stated isafe provided them with useful information -No significant differences in SVAWs score nor CESD-R score overall -The interactive, individualized Web-based isafe decision aid was effective in reducing IPV exposure limited to indigenous Māori women. -reduction of depression was significant for Maori women post trial; but was not observed at 3 and 6 months |

| MacMillan. H.L. et al. (2006) [70]. |

Women ages 18 to 64 years English-speaking Setting: 2 Emergency Departments, 2 Family practices, 2 Women’s health clinics N = 2416 women |

Intervention Type: Cluster RCT (3 arms) Intervention: Screening: Face-to-Face, Computer based, Paper based Duration: 8 months (May 2004 to January 2005) Follow-up: NA Intervention Group: Computer Based Screening (769 participants) Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: -Prevalence of IPV (3 scales used): -Partner Violence Screen (PVS), -Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) -Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) -Extent of missing data -Participant preference |

Control group(s): (1) Face-to-face interview with a health care provider (853 participants) (2) written self-completed questionnaire (839 participants) |

−12-month prevalence of IPV ranged from 4.1 to 17.7%, depending on screening method, instrument, and health care setting -No statistically significant main effects on prevalence were found for method or screening instrument, - A significant interaction between method and instrument was found -Face-to-face approach was least preferred by participants |

| McNutt L. A.et al. (2005) [71] |

Women, 18 to 44 years Setting: community health center N = 211 women |

Study Type: RCT (3 arms) Intervention: Short Computer screening Duration: one session for the web component; 2-weeks for the Booster Follow-up: NA Intervention group: n: unknown Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: Sensitivity analysis |

Control Group: n: unknown Arm2: Short Face-to-face screening with a nurse Arm3: Long computer screening |

The two computerized screening protocols were more sensitive and less or similarly specific than documented nursing staff screening |

| Renker, P. R., & Tonkin, P. (2007) [72] |

Postpartum Women at Level III maternity units in two hospitals N = 519 |

Study Type: Cross-sectional Survey Intervention: Computerized Questionnaire + voice and Video Duration: N/A Follow-up: NA Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: (1) Participants’ evaluations of the A-CASI interview to screen for perinatal abuse(2) Participants’ preferences for mode of violence screening (face-to-face, written form, or computer) (3)Participants’ perceptions of the truthfulness and completeness of their answers on the A-CASI (4) Anonymity associated with the A-CASI affect women’s perceptions of their truthfulness when responding to the questions? (5) the relationship between the women’s abuse status and preferences for mode of screening, self-report of truthfulness, and evaluation of the A-CASI interview (6) The relationship of age, source of healthcare, and race to preference for mode of screening, self-report of truthfulness, and evaluation of the A-CASI interview |

No Control Group |

Women overwhelmingly preferred computerized screening for violence over face-to-face and written formats. Including computer violence screening for all women, regardless of point of care, age, economic, or racial and ethnic background. |

| Rhodes et al. (2002) [74] |

Women and Men 18–65 Presented for emergency care with a nonurgent complaint Triaged into the lowest 2 categories of our 5-level triage system Setting: Urban emergency department N = 248 (170 women, 78 men) |

Study Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: Computer screening (generate health advice and patient risk summaries physicians) Duration: NA Follow-up: NA Intervention Group 248 (women and men) (170 women) Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: -Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS) -Partner Violence Screen (PVS) -items from Improving Health Care Response to Domestic Violence: A Resource Manual for Health Care Providers |

Control Group: 222 (women and men) usual care |

Disclosure Disclosure in the Intervention Group was significantly higher than Control: 19 cases (17 women + 2 men) out of potential 83 potential cases vs. 1 case in control (no gender reported) Detection Substantially higher detection rate of IPV in intervention group compared to control group; but it did not guarantee charting and follow-up by the treating physician |

| Rhodes et al. (2006) [73] |

women ages 18 to 65 years non-emergent female patients Setting: Emergency Departments (Urban and Suburban) N = 1281 women |

Study Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: self-administered computer-based health risk assessment, with a prompt for the health care provider Duration: 7 months (June 2001 and December 2002) Follow-up: NA Intervention Group: 637 women Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: (assessed by audiotape analysis) Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS) Partner Violence Screen (PVS) -rates of discussion of DV, -patient disclosure of DV to the health care provider, -evidence of DV services provided during the visit (safety assessment, counseling by the health care provider or social worker, or referrals to DV resources) Secondary Outcomes -Medical chart documentation of DV screening (positive or negative) -DV “case finding” (chart documentation of current or past DV), -overall patient satisfaction |

Control group: 644 usual care |

-Rates of current DV risk on exit questionnaire were 26% in the urban ED and 21% in the suburban ED Primary Outcomes - In the urban ED, the computer prompt increased rates of DV discussion, disclosure, and services provided. - Women at the suburban site and those with private insurance or higher education were much less likely to be asked about experiences with abuse. - Only 48% of encounters with a health care provider prompt regarding potential DV risk led to discussions. - Inquiries about, and disclosures of, abuse were associated with higher patient satisfaction with care. |

| Scribano et al. (2011) [75] |

Caregivers (male and female) of children in a pediatric ED Setting: Pediatric Emergency Departments N = 13,057 computerized screens |

Study Type: Observational Intervention: Home safety screening kiosks Duration: 15 months (October 1, 2008, to December 31, 2009) Follow-up: NA Intervention Group: 13,057 computerized screens in an ED Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: Partner Violence Screen (1) evaluate the feasibility of adjunctive, caregiver-initiated computer technology in a pediatric ED visit to determine home safety risks (2) determine the system reliability (technology failure rate). |

Control group: Face-to-Face screening |

13.7% among those who used the kiosks were positive for IPV High adoption of the e-screening kiosk High Reliability of Technology (downtime 4.2% of days) Need of champions to increase adoption rate |

| Sprecher. A. G. et al. (2004) [76]. |

All female patients from the 1996 ED database Setting: A Medical Center Visits N = 19,830 patient’s data |

Type of Study: Observational (retrospective) Intervention: Neural Network Model (The model was a two-layer network without any hidden processing layers. Both the input and output layers consisted of 100 elements yielding 10,000 connections between the elements.) Duration: NA Follow-up: NA Intervention Group: 19,830 records Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: Ability of a neural network model to identify potential victims of IPV using patient’s data |

No control group |

- The Neural Network identified 231 of 297 known IPV victims (sensitivity 78%) - The Neural Network categorized 2234 false-positive patients out of 19,533 IPV-negative patients (specificity 89%) |

| Thomas. C.R. et al. (2005) [77]. |

women referred by mental health screening and treatment of domestic violence Setting: rural women’s shelter program N = 35 women in total |

Intervention Type: Open trial, without control and randomization Intervention: Psychiatric evaluation and treatment provided using telepsychiatry Duration: NA Follow-up: NA Intervention group: 38 women Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: Descriptive Patient satisfaction questionnaire Improving mental health services for victims of domestic violence |

No control group |

•most commonly identified disorders were anxiety and major affective disorders, followed by substance use disorders Goal reached: Out of the 38 cases screened, 35 (92%) completed the evaluation, 31 (82%) began treatment, and 20 (53%) were transferred to ongoing outpatient care. |

| Trautman. D. E. et al. (2007) [78]. |

women ages 18 years or older Setting: Emergency Department N = 1005 women in total |

Study Type: RCT (2 arms) Intervention: Computer-based health survey for IPV screening Duration: 6 weeks Follow-up: NA Intervention group: 411 women Primary Outcomes and Measurements Tools: Outcomes screening, detection, referral and service rates |

Control group: 594 usual intimate partner violence care (screened voluntarily by ED providers and documented in medical record). |

- 99.8% of intervention participants were screened for intimate partner violence compared to 33% of control participants -computer-based health survey detected 19% intimate partner violence positive whereas usual care detected 1% -Subjects in the intervention group received intimate partner violence services more than subjects in the usual care (4% vs 1%) |

aLegend: 1 = Random sequence used; 2 = Allocation concealed; 3 = Study participants blinded; 4 = Research personnel blinded; 5 = Outcome assessment blinded; 6 = Attrition low; 7 = Non-selective reporting

Table 5.

Primary outcomes in the included studies

| Study | Screening and Disclosure | IPV Prevention | ICT Suitability | Support | Mental Health | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | NVQ | IPVEQ | DA/DA-R | PVS | AI | AAS | WAST | CAS | CTS2 | CTS2S | SVAWS | CSQ-8 | SUS | PRQ | ISEL | DCS | GSE | PROMIS | LEC-5 | SLESQ | DASS | PCL | CESD-R | PCL-C | CESD | SCL-90-R | |

| Ahmad et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bacchus et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Braithwaite et a. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chang et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Choo et al. | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constantino et al. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eden et al. | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fincher et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fiorillo et al. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ford-Gilboe et al. (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gilbert et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glass et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hassija et al. | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hegarty et al. (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Humphreys et al. | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Koziol-McLain et al. | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MacMillan | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| McNutt et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Renker & Tonkin | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rhodes et al. (2002) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rhodes et al. (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scribano et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sprecher et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thomas et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trautman et al. | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legend: CTS2 Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, CTS2S Revised Conflict Tactics Scales–Short Form, CSQ-8 Client Satisfaction Questionnaire, SUS Systems Usability Scale, IPVEQ IPV Experience Questionnaire, PRQ the Personal Resource Questionnaire, ISEL the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List, PROMIS Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, DA Danger Assessment, DA-R DA-Revised, DCS Decisional Conflict Scale, LEC-5 Life Events Checklist, SLESQ Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire, PCL-5 PTSD Checklist, DASS Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, CESD-R Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised, PCL-C PTSD checklist, Civilian Version, GSE Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale, SVAWS Severity of Violence Against Women Scale, PVS Partner Violence Screen, WAST Woman Abuse Screening Tool, CAS Composite Abuse Scale, AAS Abuse Assessment Screen, SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90-R, NVQ Non-Validated Questionnaire, AI Artificial Intelligence

Authors’ contributions

ML contributed in searching for articles, analysing their content, completing a first categorization of themes. CE contributed to searching for articles and analysing their content, comparing ML results with his, he finalized the themes, interpreted the results, designed and populated the figures and tables and wrote the current version of the paper. CE supervised and coached ML during the process. All Authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Christo El Morr, Email: elmorr@yorku.ca.

Manpreet Layal, Email: manpreet_layal@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Intimate partner violence Philadelphia. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UN News Center . UN sounds alarm to end ‘global pandemic’ of violence against women. New York: United Nations; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Human Rights Council. Work of the human rights council (2006 – present) and the commission on human rights (until 2006). New York: United Nations; 2006. [updated March 15th, 2006. Available from: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/vaw/v-hrc.htm.

- 4.Garcia-Moreno C, Watts C. Violence against women: an urgent public health priority. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(1):2. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.085217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasir K, Hyder AA. Violence against pregnant women in developing countries: review of evidence. Eur J Pub Health. 2003;13(2):105–107. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heise LL, Raikes A, Watts CH, Zwi AB. Violence against women: a neglected public health issue in less developed countries. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(9):1165–1179. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell J, García-Moreno C, Sharps P. Abuse during pregnancy in industrialized and developing countries. Violence Against Women. 2004;10(7):770–789. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Roeher Institute . Violence against women with disabilities. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koziol-McLain J, Vandal AC, Wilson D, Nada-Raja S, Dobbs T, McLean C, et al. Efficacy of a web-based safety decision aid for women experiencing intimate partner violence: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2018;19(12):e426. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poushter J. Smartphone ownership and internet usage continues to climb in emerging economies. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neil AL, Batterham P, Christensen H, Bennett K, Griffiths KM. Predictors of adherence by adolescents to a cognitive behavior therapy website in school and community-based settings. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(1):e6. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Usher W. General practitioners' understanding pertaining to reliability, interactive and usability components associated with health websites. Behav Inform Technol. 2009;28(1):39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vázquez G, Roca J, Blanch L. The challenge of web 2.0-based. Med Intensiva. 2009;33(2):84–87. doi: 10.1016/s0210-5691(09)70686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zarinah MK, Siti SS. A web-based requirements elicitation tool using focus group discussion in supporting computer-supported collaborative learning requirements development. Int J Comput Internet Manag. 2009;17:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott R. Delivering quality-evaluated healthcare information in the era of web 2.0: design implications for Intute: health and life sciences. Health Inf J. 2010;16(1):5–14. doi: 10.1177/1460458209353555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuosmanen L, Jakobsson T, Hyttinen J, Koivunen M, Välimäki M. Usability evaluation of a web based patient information system for individuals with severe mental health problems. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(12):2701–2710. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wanner M, Martin-Diener E, Bauer G, Braun-Fahrlander C, Martin BW. Comparison of trial participants and open access users of a web-based physical activity intervention regarding adherence, attrition, and repeated participation. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(1):e3. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gluck TM, Maercker A. A randomized controlled pilot study of a brief web-based mindfulness training. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):175. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maret P, Vercouter L, El Morr C. Special issue on web intelligence and virtual communities. Editorial. Int J Netw Virtual Organ. 2011;9(3):211–213. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nijhof SL, Bleijenberg G, Uiterwaal C, Kimpen JLL, van de Putte EM. Fatigue in teenagers on the interNET - the FITNET trial. a randomized clinical trial of web-based cognitive behavioural therapy for adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome: study protocol. ISRCTN59878666. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]