Abstract

Objectives

Daily numbers of COVID-19 in Singapore from March to May 2020, the cause of a surge in cases in April and the national response were examined, and regulations on migrant worker accommodation studied.

Methods

Information was gathered from daily reports provided by the Ministry of Health, Singapore Statues online and a Ministerial statement given at a Parliament sitting on 4 May 2020.

Results

A marked escalation in the daily number of new COVID-19 cases was seen in early April 2020. The majority of cases occurred among an estimated 295 000 low-skilled migrant workers living in foreign worker dormitories. As of 6 May 2020, there were 17 758 confirmed COVID-19 cases among dormitory workers (88% of 20 198 nationally confirmed cases). One dormitory housing approximately 13 000 workers had 19.4% of residents infected. The national response included mobilising several government agencies and public volunteers. There was extensive testing of workers in dormitories, segregation of healthy and infected workers, and daily observation for fever and symptoms. Twenty-four dormitories were declared as ‘isolation areas’, with residents quarantined for 14 days. New housing, for example, vacant public housing flats, military camps, exhibition centres, floating hotels have been provided that will allow for appropriate social distancing.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted migrant workers as a vulnerable occupational group. Ideally, matters related to inadequate housing of vulnerable migrant workers need to be addressed before a pandemic.

Keywords: occupational health practice, migrant workers

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Millions of low-skilled migrant workers live in housing conditions where social distancing is difficult to practise, with poor hygiene. During a pandemic, these housing sites could be flash points for spread of infection among these workers.

What are the new findings?

From early April 2020, a marked escalation of new cases of COVID-19 was observed among low-skilled migrant workers living in dormitories in Singapore. By 6 May 2020, these infected workers formed 87.9% of the 20 198 cases of cases of COVID-19 confirmed in Singapore.

How might this impact on policy or clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Unsatisfactory housing and social overcrowding in accommodation for low-skilled migrant workers need to be addressed before any pandemic occurs. If this is not done, epicentres of the disease can arise in these housing areas. Once they occur, management of these localised outbreaks have to be swift and comprehensive, in order to avoid spillover infections to the general population.

Introduction

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that there are 244 million migrants around the world.1 A significant number of these migrants are low or semiskilled workers, who live under conditions that pose concerns of social overcrowding and unsatisfactory hygiene. While their housing conditions have generally improved over the years, the conditions are not ideal for a pandemic situation. COVID-19 has highlighted the vulnerability of migrant workers as an occupational group.

Singapore is an island city-state of 721 square kilometres and a population of 5.7 million residents. It has over a million migrant workers, among which several hundred thousand low-skilled migrant workers live in dormitories. Approximately 200 thousand workers are housed in 43 large purpose-built dormitories of over a thousand residents. The larger dormitories can house 3000 to 25 000 workers and are designed for communal living, with common recreational facilities, mini grocery stores and remittance services, and are managed by operators regulated by the Ministry of Manpower. The residents are mainly males from South Asia employed in the construction, marine and other low wage sectors. In addition, there are about 1200 factory-converted dormitories (which can accommodate 50–500 workers) that house another 95 000 workers. Another 20 000 workers live in construction temporary quarters at their worksites, usually with <40 persons per site.2

Methods

The number of daily new cases of COVID-19 in March, April and early May 2020 in Singapore; the cause of a surge of cases in April 2020; the national response to the huge increase in cases; and regulations on migrant worker accommodation were examined.

Information was gathered from daily reports provided by the Ministry of Health, Singapore.3 These reports provided information on the number of newly diagnosed cases, and the distribution of the cases among imported cases who arrived to Singapore from overseas, and non-imported cases. The non-imported cases are categorised into Community Cases (residents and employment pass holders excluding work permit holders and dormitory residents), work permit holders not residing in dormitories and work permit holders residing in dormitories.

Migrant workers in Singapore can either hold an Employment Pass or a Work Permit. Skilled workers earning more than SGD3600 per month hold employment passes, while Work Permit holders are semiskilled workers working in the construction, manufacturing, marine shipyard, process or services sector.4

The principal legislation relating to the housing of migrant workers in dormitories was examined from the Singapore Statues online website.5 Additional information was gathered from a Ministerial statement given in a Singapore Parliament sitting on 4 May 2020.2

Results

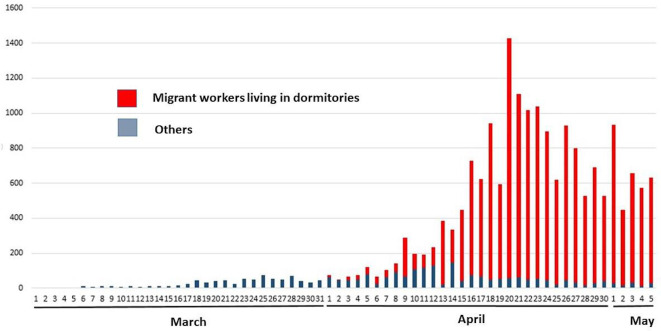

In Singapore, cases of COVID-19 are confirmed by a positive finding of a nasal swab which undergoes PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2. The total number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 increased from 105 on 1st March, to 226 on 15th March, 926 on 31st March, 3699 on 15th April, 16 169 on 30th April 2020 and 20 198 on 6th May 2020 (figure 1).3

Figure 1.

Number of new cases of confirmed COVID-19 in Singapore, 1 March–5 May 2020 [Source: Ministry of Health].

The small rise in cases in March was mainly due to ‘imported’ cases of citizens and long-term residents who returned from other infected countries. They were quarantined or given Stay at Home notices for 14 days on their return to Singapore since mid-March (depending on which country they returned from), and were monitored daily for fever and symptoms of COVID-19. From 15 to 31 March, 714 new cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in Singapore, of whom 439 (61%) were imported cases.

A surge of cases seen from early April was caused by a large number of locally transmitted infections. The majority of the new cases occurred among low-skilled migrant workers living in dormitories scattered throughout Singapore. As of 6 May 2020, there were 17 758 confirmed COVID-19 cases among those living in migrant worker dormitories (88% of 20 198 nationally confirmed cases).6 A single dormitory housing approximately 13 000 workers had 2526 confirmed cases, accounting for 12.5% of all cases in the country. Twenty-four dormitories have been declared as isolation areas, with residents quarantined for 14 days.7

The national response

The national response was swift and comprehensive. A multi-agency task force including health, manpower, military and police personnel was immediately formed. Among the sweeping measures implemented were extensive testing of dormitory workers, segregation of healthy and infected workers, observation for fever and symptoms several times a day, and setting up of dormitory on-site healthcare facilities.

The local community also helped in the response. Within days, websites that offered English to Bengali (tinyurl.com/covidbengali) and English to Tamil translations (http://better.sg/migrantworkertranslations) to medical care teams were developed. This helped overcome the language barrier and allowed non-Bengali and non-Tamil-speaking healthcare workers to conduct an initial consultation without an interpreter. The websites also enabled medical personnel to contact a group of volunteer interpreters directly. About 3000 healthcare professionals signed up to the SG Healthcare Corps since its launch in April to marshal volunteers. Many were deployed to assist in the management of the dormitory infections.

Massive logistic arrangements have been made to provide housing facilities that will allow for appropriate social distancing. These included vacant public housing flats, military camps, exhibition centres and even floating hotels. Preparations were put in place for food delivery, hygiene maintenance, monitoring and enforcement of quarantine, WiFi for workers to communicate with family and for entertainment and distribution of ‘care packs’ that contained reusable masks, hand sanitisers and thermometers.

Discussion

International recommendations for housing standards for workers have been produced by the ILO.8 In Singapore, dormitories housing over a thousand residents are regulated by the Foreign Employee Dormitories Act 2015.5 The Act provides a regulatory framework for provision of facilities and amenities, and delivery of services to residents of foreign employee dormitories. It specifies accommodation standards and mechanisms for enforcement of these standards and to promote sustainability and continuous improvements in the dormitories. A Commissioner for Foreign Employee Dormitories is responsible to administer the Act, with possible penalties imposed on dormitory operators ranging from fines of up to SGD50 000 and jail terms of up to 12 months. In 2019, 100 full-time inspectors conducted approximately 1200 inspections and 3000 investigations. Every year about 20 dormitory operators are found to breach the Act.2

In spite of these existing regulations and enforcement, conditions in the dormitories still allowed the COVID-19 outbreak to emerge. This is likely due to the difficulty to practise adequate social distancing, mingling of residents in common areas and shared facilities, for example, recreational, cooking, dining areas and toilets.

Many of the infected dormitory residents had mild symptoms, and some were even asymptomatic. These patients would not require hospitalisation and were isolated at community care facilities. As the patients are primarily young and free from significant comorbidities, their risk of serious complications and death is lower compared with the general population which has older persons at higher risk of complications and death from COVID-19. As of 6 May 2020, there has not been any deaths resulting from COVID-19 among the 17 758 infected workers. On 6 May 2020, none of these workers were hospitalised in intensive care. However, the impact on mental health among the workers should not be overlooked and needs to be addressed.

The number of cases will likely increase. Among the 3711 passengers and crew living in close proximity aboard the cruise ship Diamond Princess, 712 persons (19.2%) were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, even after quarantine and preventive measures were implemented.9 In one dormitory of about 13 000 workers in Singapore, 1123 residents (8.6%) were infected as of 17 April 2020, and by 6 May, this number increased to 2526 confirmed cases (19.4% infected residents).

Besides COVID-19, migrant workers in Singapore are at higher risk than local residents for specific infectious diseases. From 1990–2011, enteric fevers and tuberculosis cases have increased in Singapore, which could possibly be due to greater influx of migrant workers. Migrant workers accounted for half of diagnosed cases of hepatitis E, and construction workers were reported to be at higher risk of arboviral infections such as dengue, Zika and chikungunya.10

Other settings that would also face similar issues would include migrant and refugee camps,11 custodial facilities12 and nursing homes,13 which could also give rise to potential clusters of infected cases. These facilities will also pose infection risks to employees in these locations.

Ideally, matters related to inadequate housing of vulnerable migrant workers (and other similarly affected populations) need to be addressed before a pandemic. As this is unfortunately not the norm, these issues should not be disregarded but need to be urgently and conscientiously managed and resolved during a pandemic. Otherwise, these sites can be potential epicentres for COVID-19, which could subsequently lead to more widespread local transmission in the general community.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

References

- 1. International Labour Organization International labour standards on migrant workers. Available: https://www.ilo.org/global/standards/subjects-covered-by-international-labour-standards/migrant-workers/lang-en/index.htm [Accessed 17 Apr 2020].

- 2. Minister of Manpower Ministerial statement delivered in Singapore Parliament on 4 May 2020. Available: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/parliament/videos/may/ministerial-statement-josephine-teo-on-response-to-covid-19-12700868 [Accessed 7 May 2020].

- 3. Ministry of Health Singapore COVID-19 local situation report archive. Available: https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/situation-report[Accessed 7 May 2020].

- 4. Ministry of Manpower Work permit for foreign worker. Available: https://www.mom.gov.sg/passes-and-permits/work-permit-for-foreign-worker [Accessed 7 May 2020].

- 5. Singapore Statutes Online Foreign employee Dormitories Act 2015. Available: https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/FEDA2015 [Accessed 7 May 2020].

- 6. Ministry of Health Singapore Available: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/2019-ncov/situation-report-6-may-2020.pdf [Accessed 7 May 2020].

- 7. Channel news Asia interactive: COVID-19 infections at dorms and construction sites. Available: https://infographics.channelnewsasia.com/covid-19/singapore-map.html?cid=h3_referral_inarticlelinks_24082018_cna [Accessed 7 May 2020].

- 8. ILO R115 - Workers' Housing Recommendation, 1961 (No. 115). Available: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:R115 [Accessed 7 May 2020].

- 9. Moriarty LF, Plucinski MM, Marston BJ, et al. Public Health Responses to COVID-19 Outbreaks on Cruise Ships - Worldwide, February-March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:347–52. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sadarangani SP, Lim PL, Vasoo S. Infectious diseases and migrant worker health in Singapore: a receiving country's perspective. J Travel Med 2017;24. 10.1093/jtm/tax014. [Epub ahead of print: 01 Jul 2017]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tony Fallshaw T, Doyard A, Swift C, et al. Coronavirus: virus deepens struggle for migrants. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-europe-52234123/coronavirus-virus-deepens-struggle-for-migrants [Accessed 17 Apr 2020].

- 12. Kinner SA, Young JT, Snow K, et al. Prisons and custodial settings are part of a comprehensive response to COVID-19. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e188–9. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30058-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Preparing for COVID-19: long-term care facilities, nursing homes. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/long-term-care.html [Accessed 17 Apr 2020].