Abstract

Although BRAF inhibition has demonstrated activity in BRAFV600–mutated brain tumors, ultimately these cancers grow resistant to BRAF inhibitor monotherapy. Parallel activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mammalian target of rapamycin pathway has been implicated as a mechanism of primary and secondary resistance to BRAF inhibition. Moreover, it has been shown specifically that mTOR signaling activation occurs in BRAF-mutant brain tumors. We therefore conducted phase 1 trials combining vemurafenib with everolimus, enrolling five pediatric and young adults with BRAFV600-mutated brain tumors. None of the patients required treatment discontinuation as a result of adverse events. Overall, two patients (40%) had a partial response and one (20%) had 12 mo of stable disease as best response. Co-targeting BRAF and mTOR in molecularly selected brain cancers should be further investigated.

Keywords: neoplasm of the central nervous system

INTRODUCTION

BRAF-targeted therapies are U.S. Federal Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of BRAFV600-mutated melanomas, non-small-cell lung cancers, and anaplastic thyroid cancers and have demonstrated activity in a variety of other tumor types, as well (Hyman et al. 2015; Marks et al. 2018; Subbiah et al. 2018a). Unfortunately, nearly all patients ultimately exhibit resistance to BRAF-targeted therapies. A study of vemurafenib monotherapy in BRAFV600E-mutated gliomas demonstrated an objective response rate of 25% (95% CI, 10%–47%) and median progression-free survival of 5.5 mo (95% CI, 3.7–9.6 mo) (Kaley et al. 2018). Activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)–mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway leads to primary and acquired resistance to BRAF-targeted therapy in various preclinical models (Van Allen et al. 2014). Clinically, we previously identified a significantly decreased progression-free survival in patients treated with BRAF inhibitor monotherapy who harbored co-occurring mTOR pathway alterations, as well (Sen et al. 2017). Moreover, it has been shown specifically that mTOR signaling activation occurs in BRAF-mutant brain tumors and that this is associated with worse postoperative seizure outcomes (Prabowo et al. 2014; Kakkar et al. 2016). We therefore conducted a dose-escalation phase 1 trial clinical trial co-targeting both BRAF and mTOR pathways (Subbiah et al. 2018b). We included pediatric patients and primary brain tumors in this investigator-initiated clinical trial. Herein, we detail the clinical course, safety, response, and molecular profiling data of all pediatric, adolescent, and young adult patients with primary brain tumors enrolled in the phase 1 trial of vemurafenib plus everolimus.

CASE DESCRIPTION

Five patients with brain tumors harboring the BRAFV600E aberration (Table 1) were prospectively enrolled in a phase I trial of the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib in combination with mTOR inhibitor everolimus (NCT01596140).

Table 1.

Variant table

| Gene | Standardized nomenclature (HGVS) | Location | DNA change | Protein change | dbSNP ID | COSMIC ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTPN11a | NM_002834.3(PTPN11):c.226G > A p.E76K | Exon 3 | SNV | Missense | rs121918464 | COSM13000 |

| I,II. Somatic mutations | ||||||

| EPHB4b | NM_004444.4(EPHB4):c.971C > A p.P324H | Exon 6 | SNV | Missense | ||

| LRP1Bb | NM_018557.2(LRP1B):c.9120+2T > C | Splice | Sp | |||

| BRAF | NC_000007.12(BRAF):g.140099605A > T | Exon 15 | SNV | Missense | s113488022 | |

(HGVS) Human Genome Variation Society, (dbSNP) Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database, (COSMIC) Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer, (SNV) single-nucleotide variant, (Sp) splice site mutation.

aThis mutation is present at a very low allelic frequency (<5%), in discordance with the estimated tumor percentage of the sample (∼90%). Its significance is unclear.

bThese mutations are present at a very low allelic frequency (∼5%), in discordance with the estimated tumor percentage of the sample (∼90%). Their significance is unclear.

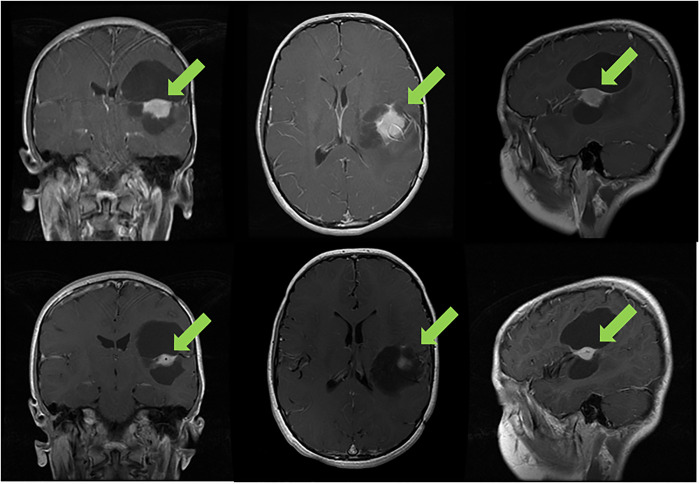

A 10-yr-old boy with World Health Organization (WHO) grade II pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA) of the left inferior parietal lobe previously treated by two surgical resections and 50.4 Gy equivalent focal proton therapy since age 4 was found to have a BRAFV600E alteration (with no other co-occurring alterations) and subsequently treated on trial with 480 mg of vemurafenib twice a day and 2.5 mg of everolimus oral daily. The tumor decreased by 32% after two cycles (Fig. 1). He had a grade 3 skin rash that required 10 d cessation of medications but improved with supportive measures, and the patient remains in partial remission now in cycle 41 with no neurological deficits, excellent performance score, and good quality of life.

Figure 1.

Progression of the tumor of a 10-yr-old boy with recurrent pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA) after multiple surgeries and radiation therapy. After two cycles of vemurafenib and everolimus, a 32% reduction was seen in the solid component of the tumor; he has stable disease for 36 mo.

A 12-yr-old girl with a right optic pathway glioma (without neurofibromatosis type 1) had disease progression after multiple chemotherapy regimens (carboplatin and vincristine, vinblastine monotherapy, vinblastine, and carboplatin) since age 1 yr old. BRAFV600E was confirmed with no other co-occurring alterations and she therefore chose to go on trial with 480 mg of vemurafenib twice a day and 2.5 mg of everolimus daily. The tumor decreased by 36% after two cycles. After five cycles, she was taken off the study as a result of noncompliance with monitoring visits.

A 37-yr-old man with a right parietal WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytoma and neurofibromatosis type 1 underwent surgical resection and 59.4 Gy focal radiation therapy (RT) with concurrent temozolomide, followed by adjuvant temozolomide. After eight cycles, an MRI showed progressive disease. Molecular profiling was obtained and revealed a BRAFV600E alteration as well as mutations in PTPN11, EPHB4, and LRP1B (Table 1). Temozolomide was switched to 150 mg of dabrafenib twice a day. One month later the patient discontinued dabrafenib as a result of disease progression and enrolled on trial and received 720 mg of vemurafenib twice a day and 5 mg of everolimus daily. After cycle 6, the tumor size was reduced by 13.7%. His disease remained stable for 12 mo on therapy.

A 22-yr-old man was initially diagnosed with a right temporal WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytoma. He underwent a subtotal resection and focal RT with concurrent temozolomide, followed by adjuvant temozolomide. Local progression with WHO grade IV glioblastoma was found soon after; he underwent subtotal resection followed by a combination of temozolomide and veliparib, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor. He was additionally treated with carmustine and 13-cis-retinoic acids. BRAFV600E mutation was identified on molecular profiling with no other co-occurring alterations, and he was subsequently treated on trial with vemurafenib twice a day, 960 mg initially, reduced to 720 mg because of severe otalgia and erythematous rash. He maintained stable for 13 mo on this regimen prior to disease progression, at which time he was treated with 720 mg of vemurafenib twice a day and 5 mg of everolimus daily for 4 mo until experiencing disease progression.

A 13-yr-old boy was initially diagnosed with a right thalamic WHO grade II diffuse astrocytoma and treated with subtotal resection and 54 Gy focal RT. Local recurrence with higher-grade glioblastoma developed 2 yr later and was treated by subtotal resection, 45 Gy re-RT with concurrent temozolomide, followed by adjuvant temozolomide. A BRAFV600E mutation with no co-occurring alterations was confirmed on molecular profiling, and the patient was treated on a different trial with vemurafenib monotherapy with stable disease for 9 mo. The patient then went on trial with a cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor and a combination of temozolomide and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, but quickly progressed on this therapy. He subsequently elected to go on trial with 720 mg of vemurafenib twice a day and 5 mg of everolimus daily. He remained on trial for 3 mo, initially with symptom improvement in his visual disturbance, weakness, and expressive aphasia, but thereafter came off study for disease progression and unfortunately passed away at age 16.

DISCUSSION

Combination therapy with BRAF and mTOR inhibition was feasible with no unexpected side effects from therapy. This also suggests that vemurafenib plus everolimus has meaningful activity in patients with BRAFV600E-mutant pediatric, adolescent, and young adult brain tumors. Dual inhibition of BRAF and mTOR was well-tolerated and no patients required termination of therapy as a result of adverse events from the study medications. Of significance, our patient with PXA has showed a partial response that continues after 41 cycles, supporting the therapeutic potential of this combination. Because of noncompliance with trial monitoring visits, our second patient with a partial response was unable to participate on trial for more than five cycles and the duration of response that would have been seen in this optic pathway glioma remains unknown.

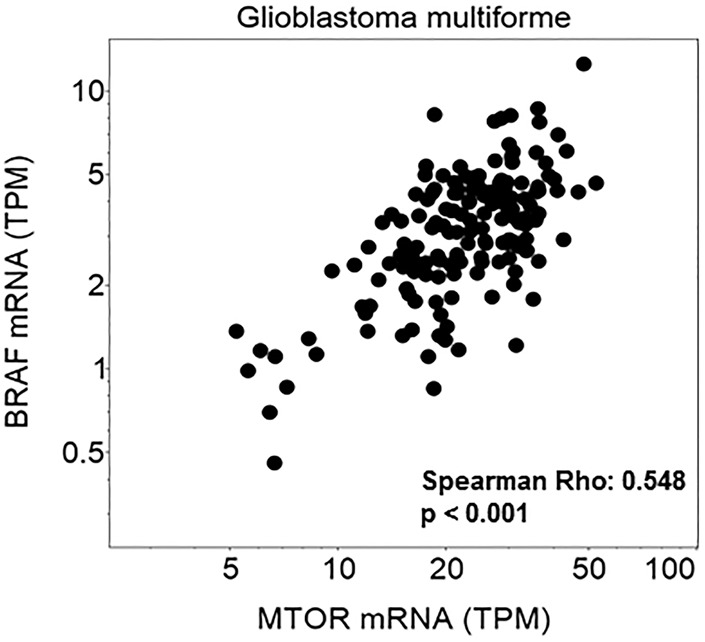

Many clinical trials exclude children and patients with brain metastases and primary brain tumors. This investigator-initiated trial allowed all of the above in addition to patients with prior BRAF therapy. In non–brain tumor patients treated with this combination, the addition of everolimus was found to overcome resistance to single-agent BRAF inhibition and/or MEK inhibition in patients with alterations in the PI3K-mTOR pathway. Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data in glioblastoma demonstrates a correlation between mTOR and BRAF expression (Fig. 2). It remains to be seen whether this will be seen in brain tumor patients who harbor PI3K-mTOR pathway alterations, as we did not have postprogression specimens in these patients.

Figure 2.

Correlation of mTOR and BRAF mRNA expression is shown in the Glioblastoma Multiforme Cancer Genome Atlas database (GBM TCGA, n = 166).

A common challenge in combining tyrosine kinase inhibitors is overlapping toxicities. This report demonstrates that the combination of vemurafenib and everolimus can be tolerated in patients with brain tumors. The patient with glioblastoma with grade 3 rash was able to continue everolimus 2.5 mg daily after pharmacologic management of the rash without toxicity.

This report has several limitations, including its small sample size and lack of molecular profiling immediately preceding trial enrollment. Ideally, all patients would have received broad-based molecular profiling at the time of study initiation and disease progression in order to better understand patterns of response and resistance to this combination of targeted therapies. Because of the low incidence and anatomical location of these tumors, this was not required for trial enrollment in the context of this trial. Moreover, brain tumors are known to demonstrate intratumoral heterogeneity (Qazi et al. 2017), and it is therefore possible that subclonal alterations were not identified.

BRAF inhibitors should continue to be evaluated as both monotherapy and combination therapy for BRAFV600 mutation–positive brain tumors. Although the responses in brain tumors seen in this trial are promising, we encourage exercising caution in interpreting these results given the small sample size and descriptive nature of the analysis. Further efforts in molecularly profiling brain tumors are needed as are more trials for the treatment of BRAFV600E-mutated brain tumors.

METHODS

We analyzed clinical cases and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified next-generation sequencing data from patients with BRAFV600-mutated CNS tumors treated on an investigator-initiated, nonrandomized, open-label, dose-escalation phase I clinical trial of vemurafenib and everolimus (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01596140) performed at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Data Deposition and Access

The variants were submitted to ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) and can be found under accession numbers SCV001424769–SCV001424772. Patient permission to deposit raw sequencing data was not granted and therefore the raw sequencing data could not be deposited.

Ethics Statement

All patients provided written consent under a protocol approved by the cancer center's Institutional Review Board (Protocol No. 2012-0153).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the patients and their families for participating in this study.

Author Contributions

The number of authors exceeds six because each of authors has the following contributions. S.S. conducted the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote and critically revised the manuscript; R.T. acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; S.K. conducted the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content; W.Z., F.J., M.P.-P., and S.-P.W. conducted the study and analyzed and interpreted the data; A.B. analyzed and interpreted the data and performed key imaging; J.R. acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data and performed statistical analysis of the data; and V.S. conceived and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding

This work was supported in part by The Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP1100584), the Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Al Nahyan Institute for Personalized Cancer Therapy, 1U01 CA180964, NCATS Grant UL1 TR000371 (Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences), and The MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA016672). The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing Interest Statement

S.S. receives research funding for clinical trials from Jacobio, Exelixis, BioAtla, Loxo Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline, Xencor, Turning Point Therapeutics, Cyteir Therapeutics; V.S. receives research funding for clinical trials from Novartis, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, NanoCarrier, Vegenics, Northwest Biotherapeutics, Berg Health, Incyte, Fujifilm, Pharmamar, D3, Pfizer, MultiVir, Amgen, AbbVie, Stemcentrx, Loxo Oncology, Blueprint Medicines, and Roche/Genentech. R.T., S.K., W.Z., F.J., M.P.-P., S.-P.W., A.B., and J.R. report no disclosures.

Referees

Peter M. Anderson

Anonymous

REFERENCES

- Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, Faris JE, Chau I, Blay J, Wolf J, Raje N, Diamond EL, Hollebecque A, et al. 2015. Vemurafenib in multiple nonmelanoma cancers with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med 373: 726–736. 10.1056/NEJMoa1502309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakkar A, Majumdar A, Kumar A, Tripathi M, Pathak P, Sharma MC, Suri V, Tandon V, Chandra SP, Sarkar C. 2016. Alterations in BRAF gene, and enhanced mTOR and MAPK signaling in dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors (DNTs). Epilepsy Res 127: 141–151. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaley T, Touat M, Subbiah V, Hollebecque A, Rodon J, Lockhart AC, Keedy V, Bielle F, Hofheinz RD, Joly F, et al. 2018. BRAF inhibition in BRAFv600-mutant gliomas: results from the VE-BASKET study. J Clin Oncol 36: 3477–3484. 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks AM, Bindra RS, DiLuna ML, Huttner A, Jairam V, Kahle KT, Kieran MW. 2018. Response to the BRAF/MEK inhibitors dabrafenib/trametinib in an adolescent with a BRAF V600E mutated anaplastic ganglioglioma intolerant to vemurafenib. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65: e26969 10.1002/pbc.26969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabowo AS, Iyer AM, Veersema TJ, Anink JJ, Schouten-van Meeteren AY, Spliet WG, Van Rijen PC, Ferrier CH, Capper D, Thom M, et al. 2014. BRAF V600E mutation is associated with mTOR signaling activation in glioneuronal tumors. Brain Pathol 24: 52–66. 10.1111/bpa.12081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qazi MA, Vora P, Venugopal C, Sidhu SS, Moffat J, Swanton C, Singh SK. 2017. Intratumoral heterogeneity: pathways to treatment resistance and relapse in human glioblastoma. Ann Oncol 28: 1448–1456. 10.1093/annonc/mdx169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S, Meric-Bernstam F, Hong DS, Hess KR, Subbiah V. 2017. Co-occurring genomic alterations and association with progression-free survival in BRAFV600-mutated nonmelanoma tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 109 10.1093/jnci/djx094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiah V, Kreitman RJ, Wainberg ZA, Cho JY, Schellens JHM, Soria JC, Wen PY, Zielinski C, Cabanillas ME, Urbanowitz G, et al. 2018a. Dabrafenib and trametinib treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic BRAF V600-mutant anaplastic thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol 36: 7–13. 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.6785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiah V, Sen S, Hess KR, Janku F, Hong DS, Khatua S, Karp DD, Munoz J, Falchook GS, Groisberg R, et al. 2018b. Phase I study of the BRAF inhibitor Vemurafenib in combination with the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus in patients with BRAF-mutated malignancies. JCO Precision Oncol 2 10.1200/PO.18.00189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Allen EM, Wagle N, Sucker A, Treacy DJ, Johannessen CM, Goetz EM, Place CS, Taylor-Weiner A, Whittaker S, Kryukov GV, et al. 2014. The genetic landscape of clinical resistance to RAF inhibition in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Discov 4: 94–109. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The variants were submitted to ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) and can be found under accession numbers SCV001424769–SCV001424772. Patient permission to deposit raw sequencing data was not granted and therefore the raw sequencing data could not be deposited.