Abstract

Infrastructural deficiencies, limited access to medical care, and shortage of health care workers are just a few of the barriers to health care in developing countries. mHealth has the potential to overcome at least some of these challenges. To address this, a stakeholder perspective is adopted and an analysis of existing research is undertaken to look at mHealth delivery in developing countries. This study focuses on four key stakeholder groups i.e., health care workers, patients, system developers, and facilitators. A systematic review identifies 108 peer-reviewed articles, which are analysed to determine the extent these articles investigate the different types of stakeholder interactions, and to identify high-level themes emerging within these interactions. This analysis illustrates two key gaps. First, while interactions involving health care workers and/or patients have received significant attention, little research has looked at the role of patient-to-patient interactions. Second, the interactions between system developers and the other stakeholder groups are strikingly under-represented.

Keywords: Mobile technology, mobile health, mHealth, stakeholder, developing countries

1. Introduction

Many factors are known to hinder health care delivery in developing countries, including infrastructural deficiencies (Avgerou, 2008; Xiao, Califf, Sarker, & Sarker, 2013) and limited access to medical care and health care workers (Scheffler, Mahoney, Fulton, Dal Poz, & Preker, 2009). The use of mobile technologies to support the realisation of health care objectives has the potential to address these issues by improving the management of health services, supply chains, and communication (Kahn, Yang, & Kahn, 2010). Strategies based around the use of such mobile technologies are collectively referred to as mobile health (mHealth) (Kahn et al., 2010; Petrucka, Bassendowski, Roberts, & James, 2013). mHealth describes the utilisation of wireless technologies to transmit and enable various health data contents and services which are easily accessible through mobile devices such as mobile phones, smartphones, PDAs (including medical sensors), laptops, and tablet PCs (Bakshi et al., 2011; Kamsu-Foguem & Foguem, 2014; Kay, Santos, & Takane, 2011).

Consequently, a role has been identified for mHealth in developing countries across a range of contexts, for example, as an incremental extension of ongoing eHealth developments in urban areas (Mars, 2013; Varshney, 2014b). Yet the advantages of mHealth are brought most keenly into focus in rural areas where little or no conventional health care infrastructure is available (Avgerou, 2008; Eze, Gleasure, & Heavin, 2016a; Kumar et al., 2013; Ngabo et al., 2012; Varshney, 2014b). In these areas, mobile devices can be rapidly deployed as a means of improving health interventions (Chang et al., 2011; Dammert, Galdo, & Galdo, 2014; Mars, 2013; Petrucka et al., 2013; Varshney, 2014b), preventing communicable diseases (Piette et al., 2012; Varshney, 2014b), and improving the health literacy of patients and health care workers (Ajay & Prabhakaran, 2011; Pimmer et al., 2014; Varshney, 2014b).

However, while existing research has highlighted many areas of potential for mHealth in developing countries, the nascent nature of the phenomenon makes it hard to relate various findings from different studies into one holistic body of knowledge, meaning it is difficult to determine areas of convergence and oversight (Chib, 2010; Chib, van Velthoven, & Car, 2015). In particular, while it is clear that mHealth systems involve a range of stakeholders with different backgrounds, it is not obvious the extent to which interactions between each of these stakeholders have been studied. Therefore, the objective of this study is to identify and synthesise existing research on the introduction of mHealth in developing countries. The rest of the paper is organised as follows. In Section 2, we discuss stakeholder theory and identify the types of common stakeholder groups identified in mHealth research. In Section 3, we present the methodology, including the search for existing research, screening and exclusion processes, and the coding of the sampled literature. In Section 4, we synthesise the findings of the reviewed literature according to the interactions they describe between stakeholders. Finally, in Section 5, we consider the contributions and implications of study for research and practice.

2. A stakeholder perspective

Stakeholder theory emerged in the management literature during the 1960s and 1970s (Ansoff, 1965; Rhenman, Stymne, & Palm, 1973) and grew in popularity across the following decades (Carroll & Nasi, 1997; Freeman, 2010). The term stakeholder refers to “those groups without whose support the organisation would not exist” (Freeman, in Pouloudi, 1999, p. 1); thus, the key principle of stakeholder perspective is that a firm/corporation enables groups of people to unite in order to create value (Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Freeman, 2010; Harrison & Wicks, 2013).

Beyond the management literature, a stakeholder perspective has proven valuable for Information Systems (IS) scholars (Ahn & Skudlark, 1997; Pan, 2005; Pouloudi, 1999). This is partly as a means to understanding more of the process requirements involved in system design (Sharp, Finkelstein, & Galal, 1999) and partly as a means to managing conflicts or diverging interests that may otherwise lead to project abandonment (Bailur, 2006; Pan, 2005). Of note to this study, stakeholder theory has also been highlighted as having particular relevance to the design of health care systems, due to the many stakeholder groups involved (Elms, Berman, & Wicks, 2002; Werhane, 2000).

Stakeholder theory has three main components: (1) the descriptive, (2) the normative, and (3) the instrumental (Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Hendry, 2001). The descriptive component “describes the corporation as a constellation of cooperative and competitive interests possessing intrinsic value” (Donaldson & Preston, 1995, p. 66). An example of the descriptive component can be seen in Jawahar and McLaughlin (2001), who used stakeholder theory to describe the uneven importance of different stakeholder groups at different points in an organisational lifecycle. In health care systems, examples of these stakeholder groups may include patients (without whom the system has no purpose), health care workers (without whom interventions to patient health could not be made), and administrative personnel (without whom the system would not be financially or practically sustainable over long periods) (Werhane, 2000). The normative component requires that actors accept the following ideas: “stakeholders are persons or groups with legitimate interests in procedural and/or substantive aspects of corporate activity, ‘the interests of all stakeholders are of intrinsic value’ and ‘a system is managerial in the broad sense of that term’” (Donaldson & Preston, 1995, p. 67). This is also relevant to health care systems, as it positions a moral responsibility at the heart of stakeholder theorising (Nyemba-Mudenda & Chigona, 2013). The instrumental component “establishes a framework for examining the connections, if any, between the practice of stakeholder management and the achievement of various corporate performance goals” (Donaldson & Preston, 1995, pp. 66–67). This is especially important to mHealth research, as the novelty of mHealth systems means the goal-oriented design of systems is ongoing.

Following our initial exploratory review of mHealth across a range of contexts, four main stakeholder groups (illustrated in Table 1), i.e. Patients, Health care Workers (HCWs), System Developers, and Facilitators were identified. Health care workers are defined in this study as those individuals who are directly responsible for one or more aspects of health care delivery. This characterisation is in line with the WHO description of health systems “as comprising all activities with the primary goal of improving health – inclusive of family caregivers, patient–provider partners, part-time workers (especially women), health volunteers and community workers” (WHO, 2006, p. xvi). Several subgroups of Health care Workers were identified in existing mHealth literature. This includes Health care Workers with minimal training, e.g., rural/community health care workers whose main responsibility is to find patients in small villages in need of remote referral (Bakibinga, Kamande, Omuya, Ziraba, & Kyobutungi, 2017; Gupta, Chawla, Dhawan, & Janaki, 2017; Hufnagel, 2012; Littman-Quinn et al., 2011; Mars, 2013; Prinja et al., 2016), mid-level health care workers often times take the place of a doctor due to lack of doctors in developing countries (e.g., Afridi & Farooq, 2011; Knoble & Bhusal, 2015; Nchise, Boateng, Shu, & Mbarika, 2012), and highly skilled remote medical experts around the world, who receive data and return recommendations via SMS or email (Kamsu-Foguem & Foguem, 2014; Littman-Quinn et al., 2011; Mars, 2013). Other stakeholders include general caregivers, who are responsible for monitoring the real-time status of vital signs of patients (Haberer, Kiwanuka, Nansera, Wilson, & Bangsberg, 2010; Kamsu-Foguem & Foguem, 2014; Kay et al., 2011; Mavhu et al., 2017) and laboratory staffers send test results to clinics in order to reduce the time in physical transportation delays (Hao et al., 2015; Hufnagel, 2012).

Table 1. Stakeholders identified in existing mHealth literature.

| Stakeholder | Subgroups identified | Literature identifying subgroups |

|---|---|---|

| Patient | Sick or ill people | Chandra, Sowmya, Mehrotra, and Duggal (2014), Hufnagel (2012), Mavhu et al. (2017), Soto-Perez-De-Celis et al. (2017), Stephan et al. (2017), Van Olmen et al. (2017) |

| Pregnant women/mothers | Alam, Khanam, and Khan (2010), Lund et al. (2012), Ngabo et al. (2012) | |

| Elderly | Chib, Wilkin, and Hoefman (2013), Kamsu-Foguem and Foguem (2014), Varshney (2014a) | |

| Women | Chandra et al. (2014), Chib and Chen (2011), Lund et al. (2012) | |

| Children | Danis et al. (2010), Florez-Arango, Iyengar, Dunn, and Zhang (2011), Hufnagel (2012) | |

| Public/Community members | Kay et al. (2011); Li, Moore, Akter, Bleisten, and Ray (2010), Prieto et al. (2017), Sharma, Banerjee, Ingle, and Garg (2017), Simon and Seldon (2012) | |

| Health care workers | Health care workers | DeRenzi et al. (2011), Hufnagel (2012), Knoble and Bhusal (2015), Van Olmen et al. (2017) |

| Clinicians | DeRenzi et al. (2011), Hufnagel (2012), Stephan et al. (2017), Vélez, Okyere, Kanter, and Bakken (2014) | |

| Community health workers | Haberer et al. (2010), Mars (2013), Mavhu et al. (2017), Surka et al. (2014), Yousuf Hussein et al. (2016) | |

| Carers/Caregivers | Bigna, Noubiap, Kouanfack, Plottel, and Koulla-Shiro (2014), Kay et al. (2011), Lucas (2014), Mavhu et al. (2017) | |

| Health workers | Alam et al. (2010), Chang et al. (2011), Piette et al. (2012) | |

| Frontline health providers | DeRenzi et al. (2011), Hufnagel (2012), Kamsu-Foguem and Foguem (2014), Yepes, Maurer, Viswanathan, Gedeon, and Bovet (2016) | |

| Counsellors | Bediang et al. (2014), Chandra et al. (2014), Jamison, Karlan, and Raffler (2013), Mavhu et al. (2017) | |

| Laboratory staffers | Hao et al. (2015), Sanner, Manda, and Nielsen (2014) | |

| Midwives | Chib and Chen (2011), Hufnagel (2012), Vélez et al. (2014) | |

| Nurses | Florez-Arango et al. (2011), Littman-Quinn et al. (2011), Mavhu et al. (2017), Soto-Perez-De-Celis et al. (2017), Zargaran et al. (2014) | |

| Physicians | Florez-Arango et al. (2011), Kay et al. (2011), Littman-Quinn et al. (2011) | |

| Doctors | Hao et al. (2015), Hufnagel (2012), Lucas (2014) | |

| Health/Medical professionals | Littman-Quinn et al. (2011), Mars (2013), Pimmer et al. (2014), Prieto et al. (2017), Stephan et al. (2017) | |

| Specialists/Experts | Afridi and Farooq (2011), Kamsu-Foguem and Foguem (2014), Littman-Quinn et al. (2011), Mars (2013), Prieto et al. (2017) | |

| System developers | Developers | Hufnagel (2012), Knoble and Bhusal (2015), Kumar et al. (2013), Surka et al. (2014) |

| Software developers | Littman-Quinn et al. (2011), Stephan et al. (2017), Tran et al. (2011), Vélez et al. (2014) | |

| Systems designers | Bakshi et al. (2011), Kamsu-Foguem and Foguem (2014), Kay et al. (2011), Stephan et al. (2017) | |

| ICT designers/developers | Ashar, Lewis, Blazes, and Chretien (2010), Chib et al. (2013) | |

| Application developers | Craven, Lang, and Martin (2014), Sanner, Roland, and Braa (2012), Varshney (2014a) | |

| Ministry of health | Hao et al. (2015), Hufnagel (2012), Mavhu et al. (2017), Ngabo et al. (2012), Yepes et al. (2016) | |

| Facilitators | District health offices | Kay et al. (2011), Mavhu et al. (2017), Nchise et al. (2012), Sanner et al. (2014), Sharma et al. (2017) |

| Research institution | Craven et al. (2014), Littman-Quinn et al. (2011), Soto-Perez-De-Celis et al. (2017), Thapa, Bidur, and Shakya (2016), Van Dam et al. (2017) | |

| Provider org./NGOs | Craven et al. (2014), Kumar et al. (2013), Littman-Quinn et al. (2011), Van Olmen et al. (2017), Yepes et al. (2016) | |

| Network service providers | Medhanyie et al. (2015), Sanner et al. (2012), Soto-Perez-De-Celis et al. (2017), Varshney (2014a) |

Patients are defined in this study as vulnerable individuals whom the mHealth systems are intended to help. Notable among these are women, either as a general group (Chandra, Sowmya, Mehrotra, & Duggal, 2014; Chib & Chen, 2011; Lund et al., 2012) or specifically pregnant women/mothers (Alam, Khanam, & Khan, 2010; Lund et al., 2012; Ngabo et al., 2012). Other groups were characterised as vulnerable due to their age, i.e., children (Danis et al., 2010; Florez-Arango, Iyengar, Dunn, & Zhang, 2011; Hufnagel, 2012) and the elderly (Chib, Wilkin, & Hoefman, 2013; Kamsu-Foguem & Foguem, 2014; Müller, Khoo, & Morris, 2016; Soto-Perez-De-Celis et al., 2017; Varshney, 2014a). More broadly, this also includes the sick or ill members of the society (Aggarwal, 2012; Chandra et al., 2014; Holl, Munteh, Burk, & Swoboda, 2017; Hufnagel, 2012) and the targeted public or community members for general health promotion/education (Kay et al., 2011; Li, Moore, Akter, Bleisten, & Ray, 2010; Modi et al., 2015; Sharma, Banerjee, Ingle, & Garg, 2017; Simon & Seldon, 2012).

System Developers are defined as those individuals directly involved in the design or/and development of an mHealth artefact. Most of these individuals identified in existing literature were primarily technical in nature, e.g., application developers (Hufnagel, 2012; Knoble & Bhusal, 2015; Surka et al., 2014); software developers (Littman-Quinn et al., 2011; Tran et al., 2011; Vélez, Okyere, Kanter, & Bakken, 2014); and ICT designer/developer (Ashar, Lewis, Blazes, & Chretien, 2010; Chib et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2013). Several studies also pointed to the role of designers, specifically system designers (Matheson et al., 2012; Ngabo et al., 2012; Piette et al., 2012; Stephan et al., 2017), and the application designers (Aggarwal, 2012; Ashar et al., 2010; Danis et al., 2010).

Facilitators are defined as those individuals or bodies that expedite or enable the development, implementation and provision of mHealth. This includes government bodies, e.g., the health ministry (Hao et al., 2015; Hufnagel, 2012; Ngabo et al., 2012; Yepes, Maurer, Viswanathan, Gedeon, & Bovet, 2016) and its affiliates, such as district health offices (Kay et al., 2011; Nchise et al., 2012; Sanner, Manda, & Nielsen, 2014; Sharma et al., 2017) and research institutions (Craven, Lang, & Martin, 2014; Littman-Quinn et al., 2011; Thapa, KC, & Shakya, 2016). It also includes individuals working for private or semi-private organisations, such as NGOs (Craven et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2013; Littman-Quinn et al., 2011), and the network service providers (Medhanyie et al., 2015; Sanner, Roland, & Braa, 2012; Soto-Perez-De-Celis et al., 2017; Varshney, 2014a).

3. Method

3.1. Gathering literature

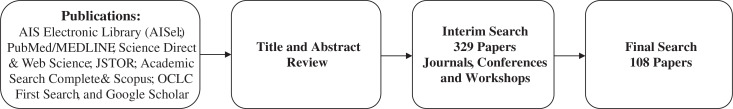

Literature was gathered from each of the leading academic databases, namely the AIS Electronic Library (AISel); PubMed/MEDLINE; Science Direct & Web Science; JSTOR; Academic Search Complete & Scopus; OCLC FirstSearch; and Google Scholar. A structured approach to searching these databases was adopted, based on an evolving set of general synonymous search terms relating to mHealth, e.g., “mHealth”, “m-Health”, “mHealth Care”, “mHealthcare”, “Mobile Health Care”, and “Mobile Healthcare”. Once the sample of literature was collected, a set of exclusion criteria were applied as part of the title and abstract review. First, literature predating 2010 was excluded. This was done because the rapidly evolving capabilities of mobile devices could have made it misleading to compare studies of mHealth systems from before this period, so compromising the internal consistency of the sample. Second, only literature written in English was included. This was because the authors were not fluent in other languages included, thus there was a significant risk that findings from those articles could have been misinterpreted, had they been included. Third, studies not using mobile devices specifically for health-related activities were excluded. Fourth, only peer-reviewed research was considered from journals, conferences, or workshops. This was done to ensure the collective body of findings was as reliable as possible. Fifth, mHealth studies that focused on technologies that did not include the following were excluded: mobile phones, smartphones, and tablets. This was done because other studies have adopted different definitions of mHealth that include, for example, mobile clinics. Sixth, studies must be focused on developing countries. This process reduced the initial set of 329 papers down to a final set of 108. Figure 1 illustrates the process while Table 2 provides a breakdown of the number of papers excluded according to each criterion.

Figure 1.

Paper review process.

Table 2. Summary of exclusion criteria.

| Exclusion criteria | Number of papers excluded |

|---|---|

| Not published since 2010 | 68 |

| Not written in English | 12 |

| Not using mobile devices specifically for health-related activities | 37 |

| Not published in peer-reviewed journals, conferences, or workshops | 21 |

| Not based on predefined mHealth technologies | 20 |

| Not focused in developing countries | 63 |

3.2. Coding of sample literature

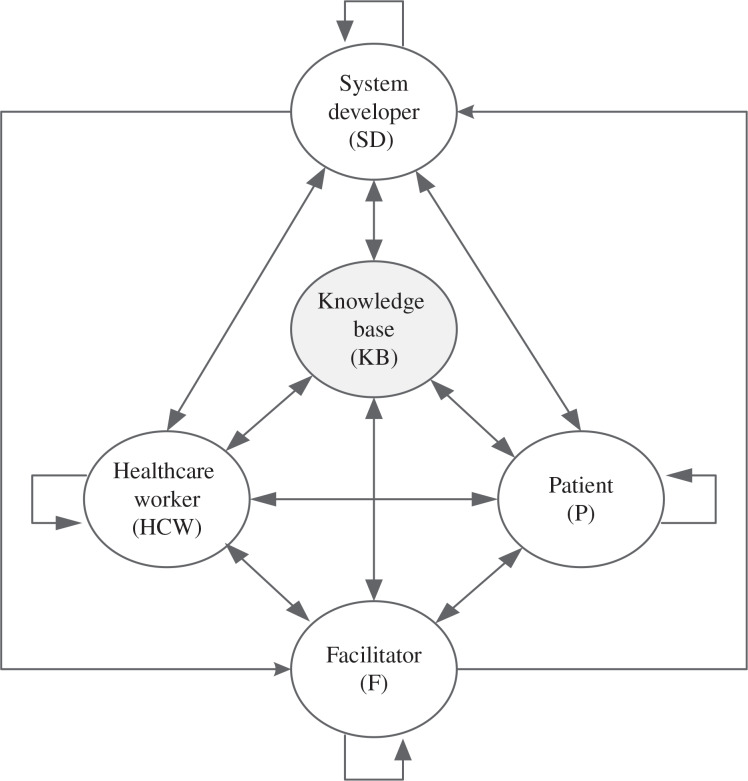

Literature was coded along two dimensions (see Figure 2 and Table 3). Previous research has suggested that health care delivery should be considered as a process (MacIntosh, MacLean, & Burns, 2007; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2011; Rubin, Pronovost, & Diette, 2001). The first commonly documented stage of this health care delivery process is prevention and education, which allows interventions to be made before individuals become seriously ill (Chandra et al., 2014; Danis et al., 2010; Ngabo et al., 2012; Piette et al., 2012). The second stage is data collection, which allows Health care Workers a means of understanding the needs of individuals and detecting issues quickly (Asangansi & Braa, 2010; DeRenzi et al., 2011; Medhanyie et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2012). The third is diagnosis, wherein Health care Workers determine the cause of an individual’s deterioration (Florez-Arango et al., 2011; Hufnagel, 2012; Knoble & Bhusal, 2015; Surka et al., 2014). The fourth is treatment, as Health care Workers act to address the deterioration through various medicines, surgeries, etc. (Alam et al., 2010; Busis, 2010; Hufnagel, 2012; Knoble & Bhusal, 2015). Each of these stages is thus mapped to the analysis of mHealth in this study, i.e., mPrevention/Education (mP/E), represents the use of mobile health (mHealth) for preventive, advisory, counselling, and educational purposes; mData-Collection (mDC) represents the use of mHealth applications to collect data that may inform other aspects of health care delivery; mDignosis (mDG) represents the use of mHealth applications for the diagnosis of specific conditions, and; mTreatment (mTM) represents the usage of mHealth systems to guide remedial health care interventions for specific Patients. In the context of this study, developing countries could be defined as countries in transition, most of which lack the necessary social, economic, and political resources to cope with a variety of problems (i.e., population growth, famine, poverty, etc.), and a huge burden of foreign debt which negatively impacts development (UNESCO, 1998).

Figure 2.

A stakeholder view of mHealth.

Table 3. Coding of papers by stakeholder interaction at each stage of mHealth delivery.

| Authors | Year | Stage of mHealth delivery | Stakeholder interaction | Types of mHealth | Country | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mP/E | mDC | mDG | mTM | PtoP | HCWtoP | PtoKB | SDtoP | HCWtoHCW | HCWtoKB | SDtoHCW | SDtoKB | FtoF | FtoP | FtoHCW | FtoSD | FtoKB | SDtoSD | ||||

| Adedokun et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Nigeria | ||||||||||||||

| Afridi and Farooq | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Pakistan | |||||||||

| Aggarwal | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS-based app | South Asia | ||||||||||

| Ajay and Prabhakaran | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | India & China | ||||||||

| Alam et al. | (2010) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Bangladesh | |||||||||||

| Armstrong et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Botswana | |||||||||||||||

| Asangansi and Braa | (2010) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Nigeria/India | ||||||||

| Ashar et al. | (2010) | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Global | |||||||||||||||

| Bakibinga et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Kenya | |||||||||||

| Bakshi et al. | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS-based app | India | |||||||||

| Balakrishnan et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | India | |||||

| Bediang et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Cameroon | |||||||||||

| Bigna et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Cameroon | ||||||||||||

| Bourouis, Zerdazi, Feham, and Bouchachia | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | SMS/MMS-based app | Algeria | |||||||||||||||

| Busis | (2010) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Developing countries | ||||||||||

| Chandra et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Bangalore | ||||||||||||

| Chang et al. | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Uganda | |||||||||||

| Chang et al. | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Uganda | |||||||||

| Chib | (2010) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Indonesia | |||||||||||

| Chib and Chen | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Indonesia | ||||||||||||||

| Chib et al. | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS-based app | Uganda | ||||||||||

| Chib et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Uganda | |||||||||||||||

| Dammert et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Peru | ||||||||||||

| Danis et al. | (2010) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS-based service | Uganda | |||||||||||||

| DeRenzi et al. | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Developing countries | ||||||||||

| DeStigter | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Uganda | |||||||||||

| Diez-Canseco et al. | (2015) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Argentina,GuatemalaPeru | |||||||||||

| Ezenwa and Brooks | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Nigeria | |||||||||||||

| Florez-Arango et al. | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Colombia | |||||||||||

| Garcia-Dia et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Voice/SMS/MMS | Philippines | |||||||||||

| Ginsburg et al. | (2015) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Ghana | |||||||

| Gupta et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | India | |||||||||

| Haberer et al. | (2010) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Uganda | ||||||||||||

| Hacking et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | South Africa | |||||||||||||||

| Hao et al. | (2015) | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Swaziland | |||||||||||||||

| Holl et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Cameroon | |||||||||||

| House et al. | (2015) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Voice/IVR app | Kenya | ||||||||||||

| Hufnagel | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | India, Tanzania, Zambia | |||||

| Istepanian et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Iraq | ||||||||

| Jamison et al. | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Uganda | ||||||||||||||

| Johnson et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Kenya | |||||||||||||||

| Kabuya et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | South Africa | ||||||||||||

| Kamsu-Foguem and Fog | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Developing countries | |||||||||||

| Kay et al. | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Developing countries | ||||||||

| Knoble and Bhusal | (2015) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Nepal | |||||||||

| Kumar et al. | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Developing countries | |||||||||

| Lemay et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS-based service | Malawi | |||||||||||||

| Leon et al. | (2015) | √ | √ | SMS app | South Africa | ||||||||||||||||

| Li et al. | (2010) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS-based service | Malawi | ||||||||

| Littman-Quinn et al. | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/MMS-based app | Botswana | ||||||||

| Lucas | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | IndiaBangladeshCambodia | |||||||||||||

| Lund et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Zanzibar | ||||||||||||

| Lwin et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Sri Lanka | |||||||||||

| Machingura et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Developing countries | ||||||||||||

| Madon et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Tanzania | ||||||||||||

| Mahmud et al. | (2010) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Malawi | |||||||||||||

| Mangone et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Tanzania | |||||||||||||

| Mars | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Africa | ||||||||

| Mavhu et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Haiti | |||||||||

| Matheson et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice app | Zimbabwe | ||||||||||||

| Medhanyie et al. | (2015) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Ethiopia | |||||||||||||

| Modi et al. | (2015) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Mobile-based app | India | ||||||||||||

| Müller et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | SMS app | Malaysia | ||||||||||||||||

| Munro et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Liberia | |||||||||||

| Nakashima et al. | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Bangladesh | |||||||||||

| Nchise et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Uganda | |||||||||||||

| Ngabo et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS-based service | Rwanda | ||||||||

| Nhavoto et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Mozambique | |||||||||||||

| Odigie et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | SMS/Voice IVR | Nigeria | ||||||||||||||||

| Osei-tutu et al. | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/MMS/IVR | Ghana | |||||||||||||

| Petrucka et al. | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Ghana | ||||||||||

| Piette et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Honduras and Mexico | ||||||||||

| Pimmer et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | South Africa | |||||||||||||||

| Pop-Eleches et al. | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice-based app | Kenya | |||||||||||||||

| Praveen et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | India | ||||||||||

| Prieto et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Mobile-base app | Guatemala | ||||||||||

| Quinley et al. | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/MMS/IVR | Botswana | |||||||||

| Rajput et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Kenya | |||||||||

| Ricard-Gauthier et al. | (2015) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Madagascar | ||||||||||||

| Rotheram-Borus et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | South Africa | |||||||||||||||

| Samelli, Rabelo, Sanches, Aquino, and Gonzaga | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Brazil | |||||||||

| Sanner et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | India | |||||||||

| Sanner et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Malawi | ||||||||||||

| Selke et al. | (2010) | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Kenya | |||||||||||||||

| Sharma et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice app | India | |||||||||||||

| Simon and Seldon | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Malaysia | |||||||||||||

| Soto-PerezDeCelis et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Mexico | ||||||||||||

| Stanton et al. | (2015) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Malawi, Ghana | |||||||||

| Stephan et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Brazil | |||||||||||

| Stine Lund et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice IVR app | Tanzania | |||||||

| Surka et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | South Africa | ||||||||||||

| Thapa et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Nepal | |||||||||

| Thondoo et al. | (2015) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice app | Uganda, Mozambique | ||||||||||

| Toda et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Kenya | |||||||||||||

| Tomita et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | SMS app | South Africa | ||||||||||||||||

| Tran et al. | (2011) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/MMS-based app | Egypt | ||||||||||||

| Van Dam et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Kenya | |||||||||||||

| Van Olmen et al. | (2017) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | DRCongo/Cambodia/Philippines | |||||||||||

| Varshney | (2014a) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Global | ||||||

| Vélez et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | Ghana | |||||||||

| Wagner et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | SMS app | Burkina Faso | ||||||||||||||||

| Wu et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | China | |||||||||||||

| Y. Zhang et al. | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | China | |||||||||||||||

| Yepes et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | √ | SMS app | Seychelles | |||||||||||||||

| Yousuf Hussein et al. | (2016) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | South Africa | |||||||||||

| Zaidi et al. | (2013) | √ | √ | √ | √ | SMS/Voice app | Pakistan | ||||||||||||||

| Zargaran et al. | (2014) | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | South Africa | ||||||||||||||

| Zhang et al. | (2012) | √ | √ | √ | √ | Mobile-based app | China | ||||||||||||||

Abbreviations: mP/E – mPrevention/Education; mDC – mDataCollection; mDG – mDiagnosis; mTM –mTreatment; PtoP – Patient to Patient; HCWtoP – Health care Worker to Patient; PtoKB – Patient to Knowledge Base; SD/P – System Developer to Patient; HCWtoHCW – Health care Worker to Health care Worker; HCWtoKB – Health care Worker to Knowledge Base; SDtoHCW – System Developer to Health care Worker; SDtoKB – System Developer to Knowledge Base; FtoF – Facilitator to Facilitator; FtoP – Facilitator to Patient; FtoHCW – Facilitator to Health care Worker; FtoSD – Facilitator to System Developer; FtoKB – Facilitator to Knowledge Base, and SDtoSD – System Developer to System Developer.

With the delivery of mHealth conceptualised, the actors involved may then be considered. The stakeholders of a system have been identified as integral to the design development and implementation of mHealth solutions (Asangansi & Braa, 2010; Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Sanner et al., 2012). This is especially important in health care contexts, wherein different groups can possess varying perceptions, attitudes, skill-sets, and behaviours (Akter, Ray, & D’Ambra, 2013; Clarkson, 1995; Varshney, 2014a). Thus, the second dimension considers the interactions between the four main groups of stakeholders. The first stakeholder group describes those involved in providing health care, i.e., the Health care Workers (HCWs) (Kay et al., 2011; Varshney, 2014a) (medical doctors, medical specialist, nurses, midwives, laboratory technicians and community health workers). The second group describes those individuals receiving health care, i.e., Patients (P) (individuals who may potentially receive preventative or curative care from the system). The third stakeholder group describes those individuals responsible for building the mHealth system, i.e., System Developers (SD). The fourth stakeholder group describes those individuals or groups that support the implementation and provision of mHealth, i.e., Facilitators (F). In considering the stakeholder view of mHealth, we place the Knowledge Base (KB) at the centre of the interactions (Figure 2). The KB is the data/information store or health information repository that underpins mHealth delivery. Interaction flows for each of these stakeholder groups are considered between that group and the KB enabled by the system, e.g., Health care Workers to Knowledge Base, between that group and other groups, e.g., System Developer to Health care Workers, and within members of that group, e.g., Health care Workers to Health care Workers. These interactions are illustrated in Figure 2.

One researcher collected and coded these papers. Samples of coding under each of the analytical headings were discussed routinely among three researchers to ensure consensus in coding.

4. Results

Analysis of the sampled literature reveals significant diversity in the stakeholder interactions studied and the methods employed. These methods include: focus groups (Chandra et al., 2014; Chib & Chen, 2011; Ly, Carlbring, & Andersson, 2012; Pop-Eleches et al., 2011; Sanner et al., 2014; Thapa et al., 2016; Tomita, Kandolo, Susser, & Burns, 2016); surveys (Armstrong et al., 2012; Chib et al., 2013; Kay et al., 2011; Piette et al., 2012; Rajput et al., 2012; Stanton et al., 2015; Yepes et al., 2016); case studies (Ezenwa & Brooks, 2013; Madon, Amaguru, Malecela, & Michael, 2014); randomised experiments (Bigna, Noubiap, Kouanfack, Plottel, & Koulla-Shiro, 2014; Florez-Arango et al., 2011); open-ended questionnaires (Lund et al., 2012; Machingura et al., 2014; Tran et al., 2011; Vélez et al., 2014); pre- and post-intervention studies (Munro, Lori, Boyd, & Andreatta, 2014; Sharma et al., 2017); pilot studies (Chib, Wilkin, Ling, Hoefman, & Van Biejma, 2012; van Dam et al., 2017; Mahmud, Rodriguez, & Nesbit, 2010; Modi et al., 2015; Osei-tutu et al., 2013); semi-structured interviews (Adedokun, Idris, & Odujoko, 2016; Nhavoto, Grönlund, & Klein, 2017); cross-sectional observational studies (House, Cheptinga, & Rusyniak, 2015); in-depth interviews (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2012; Thondoo et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2013); feasibility studies (Gupta et al., 2017; Istepanian et al., 2014; Soto-Perez-De-Celis et al., 2017); mixed methods (Chang et al., 2011, 2013; Chib, 2010; Knoble & Bhusal, 2015; Lemay, Sullivan, Jumbe, & Perry, 2012; Nchise et al., 2012); qualitative interviews (Hao et al., 2015; Jamison, Karlan, & Raffler, 2013; Matheson et al., 2012; Medhanyie et al., 2015; Pimmer et al., 2014), and action research (Asangansi & Braa, 2010; Sanner et al., 2012).

The different types of stakeholder interactions are discussed in the following sections. Further, consistent with the ethical view of stakeholders proposed by (Werhane, 2000) (and to avoid repetition), the order in which these interactions are presented reflects their centrality to health outcomes. Thus, the first section looks at the five stakeholder interactions directly involving Patients (Patient-to-Patient, Patient-to-HCW, Patient-to-SD, Patient-to-Facilitator, and Patient-to-Knowledge Base). With those interactions discussed, the second section looks at all remaining interactions involving HCWs (HCW-to-HCW, HCW-to-SD, HCW-to-Facilitator, and HCW-to-Knowledge Base). The third section then looks at all remaining interactions involving SDs (SD-to-SD, SD-to-Facilitator, and SD-to-Knowledge Base). Finally, the fourth section looks at all remaining interactions involving only Facilitators (Facilitator-to-Facilitator and Facilitator-to-Knowledge Base).

4.1. A patient perspective

4.1.1. Interaction between patients and health care workers

The interaction between Patients and HCWs were broadly studied by the sampled literature across all the four stages of mHealth delivery (see Table 4). In terms of mPrevention/Education, studies documented the opportunity afforded Patients to reach out whenever they had emotional problems or felt like talking to a HCW (Chandra et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2011; Hufnagel, 2012; Munro et al., 2014; Odigie et al., 2012). Such findings are part of a broader theme where mobile technology enables patients to be connected to remote HCWs (Armstrong et al., 2012; Bakshi et al., 2011; Hufnagel, 2012; Mahmud et al., 2010; Quinley et al., 2011; Sharma et al., 2017; Simon & Seldon, 2012), as part of which patients’ data can be collected and stored as personal health records. Such data are available to the individual to HCW responsible to the patient in the future, allowing ongoing care to accumulate (Eze, Gleasure, & Heavin, 2016b; Gupta et al., 2017; Hufnagel, 2012; Kabuya, Wright, Odama, & O’Mahoney, 2014; Simon & Seldon, 2012; Stephan et al., 2017). Specifically, these data help HCWs to diagnose those individuals, design treatments for them, and to monitor their adherence and health needs (Chib & Chen, 2011; Garcia-Dia, Fitzpatrick, Madigan, & Peabody, 2017; Hufnagel, 2012; Leon, Surender, Bobrow, Muller, & Farmer, 2015; Mahmud et al., 2010; Mars, 2013; Mavhu et al., 2017; Wagner, Ouedraogo, Artavia-Mora, Bedi, & Thiombiano, 2016).

Table 4. Patient interactions.

| Stakeholder interaction | mPrevention/Education | mData-Collection | mDignosis | mTreatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient–HCW | 74 | 76 | 53 | 54 |

| Patient–KB | 29 | 33 | 21 | 23 |

| Patient–SD | 6 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| Patient–Facilitator | 7 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Patient–Patient | 3 | 2 | – | – |

4.1.2. Interaction between patients and the knowledge base

Interactions between patients and the KB were less salient in discussions of mHealth delivery, though still extensively researched. Discussions addressing mPrevent/Education described systems where patients can send SMS questions to a KB, then receive automated SMS messages on their cell phones that provides information and reminders for their self-care (Armstrong et al., 2012; Bakshi et al., 2011; Diez-Canseco et al., 2015; Garcia-Dia et al., 2017; Hacking et al., 2016; Hufnagel, 2012; Mangone et al., 2016; Müller et al., 2016; Nhavoto et al., 2017; Odigie et al., 2012; Piette et al., 2012; Simon & Seldon, 2012; Wagner et al., 2016; Yepes et al., 2016). Patients have also been equipped with wearable devices to keep track of parameters such as blood pressure, pulse rate, temperature, weight, blood glucose are stored as relevant data in the Knowledge Base (Hufnagel, 2012; Kumar et al., 2013; Simon & Seldon, 2012). This opportunity to monitor patients’ physiological state outside of Health institutions has been identified as a key protocol in mHealth systems in the future (Ajay & Prabhakaran, 2011; Hufnagel, 2012; Mavhu et al., 2017; Munro et al., 2014; Simon & Seldon, 2012; Wagner et al., 2016).

4.1.3. Interaction between patients and system developers

Table 4 illustrates that the interactions between patients and SDs were not widely studied in the sampled literature. Of the studies that explored this aspect of mHealth, the most popular subject matter was the potential for patients to amass perceptions of poor quality of service, which is identified as a key threat for the spread of mHealth systems (Akter et al., 2013; Hufnagel, 2012; Van Olmen et al., 2017; Varshney, 2014a). Varshney (2014a) elaborates on this by laying out five variables that determine patients’ continued intention to use an mHealth system: (i) satisfaction, (ii) confirmation of expectations, (iii) perceived usefulness, (iv) perceived service quality, and (v) perceived trust. The impact of the latter two variables (perceived service quality and perceived trust) were similarly found to be vital to patients’ continued use of mHealth systems according to feedback received by Akter et al. (2013). However, cost is seen as a key threat to those Patients or individuals with scares financial resources, thus limiting mHealth programme’s reach and impact (Holl et al., 2017; Mangone et al., 2016).

4.1.4. Interaction between patients and facilitators

The interaction between facilitators and patients mostly occurred at the level of mPrevention/mEducation. In some cases, this involved notifying the public about disasters or disease breakouts (Hufnagel, 2012; Li et al., 2010; Prieto et al., 2017; Toda et al., 2016). In other cases, facilitators sought to equip patients with the means to avoid falling ill, for example by distributing chemical treatment to minimise the spread of mosquito bites or spray an area once some clinical episodes are observed (Dammert et al., 2014).

4.1.5. Interaction between patients and other patients

Interestingly, three studies in the sample explicitly addressed the interaction between patients. All three studies (Chang et al., 2011; Mavhu et al., 2017; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2012) focused on mPrevention/Education. In addition, two of these studies (Chang et al., 2011; Mavhu et al., 2017) focused on mData-Collection. In particular, observations from the country specific initiatives in Uganda, Zimbabwe, and South Africa found that patients could be trained to care for other patients to allow (1) greater health support for fellow patients (2) greater opportunity for HCWs to attend to other high-priority responsibilities in their daily schedules. Chang et al. (2011) note this approach of patient training leads to changes in information-seeking among the broader patient population, who become more likely to turn to these peer Health care Workers (PHCWs) for care than to conventional HCWs. L. W. Chang et al. (2011) remark that “as one Patient illustratively said: ‘‘I may have no money and I go to a friend. I might ask him to help me call the PHCW because the PHCW gave us their numbers. From that I will be able to explain the problems that I am going through. The PHCW will call the HCWs and they will come to attend to me’’ (Chang et al., 2011, p. 1778) (Table 5).

Table 5. Healthcare workers interactions.

| Stakeholder interaction | mPrevention/Education | mData-Collection | mDiagnosis | mTreatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCW–KB | 54 | 70 | 47 | 48 |

| HCW–HCW | 37 | 46 | 35 | 36 |

| HCW–Facilitator | 17 | 18 | 14 | 13 |

| HCW–SD | 9 | 15 | 13 | 9 |

4.2. A healthcare worker perspective

4.2.1. Interactions between healthcare workers and the knowledge base

The interaction between HCWs and KB was also extensively studied in the sampled literature across all four stages of mHealth delivery. In terms of mPrevention/Education, studies suggest that by gaining access to some established KB or health information repository, HCWs can enhance or improve their health knowledge even when residing in a resource-poor settings (Bakibinga et al., 2017; Gupta et al., 2017; Hufnagel, 2012; Pimmer et al., 2014; Thapa et al., 2016). Studies demonstrated a willingness among HCWs to gather and transmit collected patient to data national repositories or databases (Alam et al., 2010; van Dam et al., 2017; Varshney, 2014a). Further, there is evidence that these HCWs are also willing to refer to such centralised systems to guide their diagnoses and treatments at the point-of-care in developing countries (Alam et al., 2010; Hufnagel, 2012). At the facility level, it can improve the timelines for stocks replenishment as a result of automatic stock reporting system (Hufnagel, 2012; Lemay et al., 2012; Madon et al., 2014).

4.2.2. Interactions between healthcare workers and other healthcare workers

The interactions between HCWs were studied extensively by the sampled literature across all four stages of mHealth delivery. Among the literature addressing mPrevent/Education, most discussion centred upon the infeasibility of scarce HCWs to make themselves available for workshops or class-room teaching as such expectations fail to consider the practical realities of these resource-poor settings (Gupta et al., 2017; Hufnagel, 2012; Mars, 2013). This presents an important challenge, as contact with HCWs is necessary to reduce the sense of isolation experienced by rural HCWs in the developing countries (Mars, 2013; Nhavoto et al., 2017; Pimmer et al., 2014; Thondoo et al., 2015). Discussion around mData-Collection, and mTreatment were frequently combined in studies, most notably in discussion of mHealth systems with the capacity to transmit locally gathered data to medical experts located anywhere in the world. This allows those experts to make use of remote specialisation and resources to transfer their findings and diagnosis back to HCWs in the developing countries via SMS or email which can then inform Patient treatment (Chib & Chen, 2011; Hufnagel, 2012; Pimmer et al., 2014; Thondoo et al., 2015). For instance, maternal mortality is one of the biggest health problems in developing countries (Alam et al., 2010; Bakibinga et al., 2017; Chib & Chen, 2011; Medhanyie et al., 2015; Munro et al., 2014). The lack of maternal care specialists in these areas can be mitigated by sharing data from pregnant women with specialists situated in more resource-wealthy environments, who in-turn assesses different levels of risk for the Patient and help prioritise health care for those most in need (Alam et al., 2010; Chib & Chen, 2011; Medhanyie et al., 2015).

4.2.3. Interaction between facilitators and healthcare workers

The interactions between Facilitators and HCWs are typically designed to guide and improve the delivery of mHealth by the latter. In some cases, this involves improving HCWs’ ability to access and respond to data (Balakrishnan et al., 2016; Gupta et al., 2017; Madon et al., 2014; Stanton et al., 2015; Thondoo et al., 2015). For example, the Tanzania’s National Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) sponsored a scalable smart phone-based management information system to help deliver a neglected tropical disease (NTD) programme, that would empower local HCWs to take action (Madon et al., 2014). In other cases, the focus was less on centralised IT solutions and more on IT-enabled training sessions for HCWs (Hufnagel, 2012; Mars, 2013; Nchise et al., 2012; Stanton et al., 2015). The interaction between HCWs and network service providers was also discussed as a key enabler of mHealth practices, mostly because sudden interruptions or inconsistencies in telecommunications networks could devastate those in the midst of services, potentially preventing new users from engaging with mHealth technologies (Aggarwal, 2012; Stanton et al., 2015; Thondoo et al., 2015). In some cases, government bodies and network service provision have converged to interact with HCWs as one, e.g., in Ghana, the Government Millennium Village Project (MVP) is currently implementing the Millennium Village Global Network (MVG-Net), the aim of which is to closely partner the coordination of care between HCWs and MVP clinical facilities (Vélez et al., 2014).

4.2.4. Interactions between health care workers and system developers

The interaction between HCWs and SDs was the least well represented in the sampled literature across all stages of mHealth delivery. Of those studies that did address this interaction, discussion centred mostly on usability and implementation issues (e.g., Akter et al., 2013; Ginsburg et al., 2015; Stephan et al., 2017; Vélez et al., 2014). Ensuring continuous use of mHealth systems by Health care Workers is often a key determinant of their success (Akter et al., 2013; Vélez et al., 2014). Thus, collaborative design processes are undertaken between HCWs and SDs to minimise adoption issues at various parts of mHealth delivery (Akter et al., 2013; Vélez et al., 2014). This is illustrated in case studies of rural settings in developing countries, where feedback provided from HCWs to the SDs led to significant functional changes in applications (Knoble & Bhusal, 2015; Vélez et al., 2014). Collaborative design and implementation processes with HCWs have also been used to ease tensions around the introduction of mHealth systems (Ngabo et al., 2012; Vélez et al., 2014). These collaborative processes help SDs to form an in-depth understanding of HCWs’ task structure, their special mobility in places of work and the associated information technology liabilities that will ultimately influence continued usage of the IT artefact (Akter et al., 2013; Varshney, 2014a) (Table 6).

Table 6. System developer interactions.

| Stakeholder interaction | mPrevention/Education | mData-Collection | mDignosis | mTreatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD–Facilitator | 23 | 30 | 24 | 21 |

| SD–KB | 8 | 13 | 10 | 8 |

| SD–SD | 19 | 23 | 17 | 14 |

4.3. A system developer perspective

4.3.1. Interaction between facilitators and system developers

The interaction between facilitators and SDs is the translation of policies into infrastructure and working IT systems. System designers require approvals from MoH in the respective countries for the introduction of any mHealth tools regarding ethical issues (e.g., Bediang et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2011; van Dam et al., 2017; Lwin et al., 2014; Piette et al., 2012). It appears that transitioning these developed tools from the SD to MoH can be a problem if the MoH are not part of the system design from the outset (Hufnagel, 2012; Thondoo et al., 2015; van Dam et al., 2017). System Developers cannot develop devices that can communicate over a network and also be capable of running all applications required for mHealth delivery without the support of the network providers (Chib et al., 2013; Hacking et al., 2016; Thapa et al., 2016). Other challenges that SDs might encounter with the respective governments include delivering its services into the institutional framework of each country, which is facilitated if the countries concerned have an eHealth strategy and related policies and coordination structures put in place (Hufnagel, 2012; Varshney, 2014b).

4.3.2. Interaction between system developers and the knowledge base

As with other SDs-related interactions, interactions between SDs and the KB were also studied infrequently in the sampled literature. Amongst the literature addressing mPrevention/Education, much of the discussion focused on the development of new technologies that continuously improve health outcomes, quality of life, and/or that will offer solutions to emerging problems (Matheson et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014). For example, an examination of scalability issues suggested all mobile applications should be carefully designed and introduced so as to support ongoing efforts at a cohesive mobile supported health information infrastructure in developing countries (Asangansi & Braa, 2010). In the same vein, Sanner et al. (2014) recommend the concept of “grafting” as a new perspective on information infrastructure, wherein new solutions must be ‘grafted’ onto existing resources and local interested parties. New reusable system archetypes were also discussed as basic utilities. Afridi and Farooq (2011) explained the workings of OG-Miner – an intelligent health tool that presents a novel combination of data mining techniques for accurate and effective categorisation of high risk pregnant women. According to Lwin et al. (2014), Mo-Buzz – a Mobile Pandemic Surveillance System for Dengue could digitally record site visit information by public health inspectors (PHI) and track dengue outbreaks in real time using a built-in global positioning system technology. MDAU – a modular data analysis unit, which is a USB powered multiparameter diagnostic device that captures ECG, temperature, heart & lung sounds, SPO2 and BP, and communicates with the remote doctor through a low bandwidth audio/video/data conferencing (Hufnagel, 2012). This device according to Hufnagel (2012), allowed the incorporation of the whole health care delivery ecosystem in order to provide meaningful service.

4.3.3. Interaction between system developers and other system developers

The interaction between SDs and other SDs was referred to by a number of studies in the sampled literature in terms of collaborative development challenges. Most interactions in the sampled literature were focused on data collection by integrating open-source platforms. In Ethiopia, Medhanyie et al. (2015) installed and customised data collection application named Open DataKit with electronic maternal health care forms on smartphones for the assessment of pregnant women’s health by Health care Workers. In Kenya, van Dam et al. (2017) integrated an open-source CommCareHQ application with cloud infrastructure into mobile phones as job aids for rural Health care Workers. In the case of Malawi, Li et al. (2010) used an open-source kit FrontlineSMS to create an SMS-based communication hub for instantaneous data transmission between community Health care Workers and hospitals. The focus of these collaborative product development is for public availability and communication, and is usually obtained via the Internet (Table 7).

Table 7. Facilitator interactions.

| Stakeholder interaction | mPrevention/Education | mData-Collection | mDiagnosis | mTreatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitator–Facilitator | 13 | 14 | 8 | 9 |

| Facilitator–KB | 9 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

4.4. A Facilitator perspective

4.4.1. Interaction between facilitators and other facilitators

The interactions between facilitators and other facilitators described an international web of organisations, each of whom possess different areas of expertise, which interact to coordinate large mHealth projects. In Botswana, some organisations, including the Orange Foundations, the Clinton Health Access initiatives (CHAI) and the Ministry of Health of Botswana (MoH) aimed to develop ICT tools for health provision and education within the health public health sector (Littman-Quinn et al., 2011). In Ghana, PATH (Partnership for Transforming Health Systems) collaborated with the University of Washington to develop an android-enabled IMCI (Integrated Management of Childhood Illness) guideline on tablets for health care providers in rural communities in Ghana (Ginsburg et al., 2015). In Bihar, India. Care India with the support of Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation developed a public health initiative called ‘continuum of care services using mHealth tool to improve maternal and new-born health (Balakrishnan et al., 2016). In the case of Haiti, the informatics group at the International Training and Education Centre for Health (I-TECH), formed as a result of the collaborative activity between the University of Washington and University of California at San Francisco. In this instance, an electronic medical record (EMR) system called iSanté has been implemented as part of Haiti’s response to HIV (Matheson et al., 2012). The key challenge in this partnership is the facilitation of a smooth transition from a donor driven pilot oriented relationship in conjunction with the mobile operators into a business model that is sustainable where the respective ministries of health in those countries obtain the capacity to assume ownership of the programme (Sanner et al., 2012).

4.4.2. Interaction between facilitators and the knowledge base

The interaction between Facilitators and the KB typically takes the form of contributing or retrieving information for/about the public. In terms of retrieving data from the KB, one example was the Nepalese Ministry of Health’s use of data from the e-algo platform (Knoble & Bhusal, 2015). The e-algo platform was primarily used by HCWs to diagnose and treat different conditions; however, it also provided an overview of health conditions in different areas, which the Ministry of Health uses to inform the ongoing policy development. Another example was in Haiti where the Ministry of Health Ministry tracks the incidence of HIV and progress of prevention efforts store in iSanté platform (Matheson et al., 2012).

5. Conclusion

Before discussing contributions, the possible limitations of this study are outlined. First, including only studies written in English may have excluded inputs that would have added some richness to the findings of this study. For example, studies written in local languages may have provided us with deeper insights into the interactions between stakeholders that were not captured by those written in English language. Second, although the review set out to address the interactions between the pre-identified stakeholders within a country during an mHealth interventions, the actual review did not reveal any other stakeholder. This means that a continued research is needed into the breakdown of these other stakeholders within the group/s from outside looking to do mHealth interventions in a country, thereby adding high-level research trends. Third, the review was conducted at the developing countries level, the disparity or otherwise in the results of the type of mHealth, and the quality of interventions across countries was outside the scope of this study. This is an opportunity for further research into this important part in mHealth interventions in developing countries.

This study performed a literature review of mHealth research in developing countries. A preliminary review identified four high-level stakeholder groups of interest to mHealth systems, namely Health care Workers (HCWs), patients, system developers (SDs), and facilitators. A systematic review of mHealth in developing countries was performed to identify existing research, initially retrieving 329 peer-reviewed articles, which were subsequently reduced to 108 eligible studies. Studies were analysed and coded according to the stages of mHealth delivery that they described (mPrevention/Education, mData-Collection, mDignosis, and/or mTreatment) and which stakeholder interactions were studied. This allowed meta-level themes to be identified from existing research, as well as areas that have been less well considered to date. This review has made six significant contributions to IS research.

First, a contribution is made in the form of a novel two dimensional lens used to analyse the literature. This lens provided a useful (and reusable) means of sense-making for the diverse body of research in health care, revealing several important high-level trends in the analysis and design of mHealth systems in developing countries. Among these trends was a triangulated meta-level investigation of the potential of mobile phones to transform health care delivery services in resource-poor settings (e.g., Hufnagel, 2012; Kay et al., 2011; Sharma et al., 2017; Soto-Perez-De-Celis et al., 2017), to address heterogeneous information needs in rural communities (e.g., Akter et al., 2013; Ngabo et al., 2012; Piette et al., 2012; Van Olmen et al., 2017), to boost information penetration in areas where access to health information is limited (e.g., Ezenwa & Brooks, 2013; Li et al., 2010; Littman-Quinn et al., 2011; Lwin et al., 2014; Ngabo et al., 2012; Nhavoto et al., 2017; Piette et al., 2012), and to provide real-time collaborative and adaptive interventions (DeRenzi et al., 2011; Leon et al., 2015; Littman-Quinn et al., 2011; Nchise et al., 2012). The validation of these claims across multiple stakeholder perspectives and different stages in mHealth delivery reinforces the importance of the role of mHealth for these contexts.

Second, a balanced focus of mHealth was observed across each of the stages of the mHealth delivery. Several of the sampled papers report findings from pilot studies in which the maturity and reach of system implementation was limited, meaning many issues of integration and scale may yet emerge. However, the fact that mHealth efforts represent a proportional breadth of activities means that the value of each stage can be observed and discussed. For example, in India, mPrevention/Education interventions that targeted the mental health of teenage girls between the ages of 16–18 years from urban slums resulted in 62% of users feeling more supported (Chandra et al., 2014). Similarly, in low-resource settings, in Cameroun, mobile-phone-based reminders significantly increased attendance for scheduled HIV appointments with carers of paediatric patients (Bigna et al., 2014). The demonstrable success of these types of initiation paves the way for subsequent holistic endeavours in comparable contexts.

Third, analysis of the literature showed that interactions around HCWs are being extensively researched. This makes sense, given these stakeholders are likely to be the most intensive users of mHealth systems. Thus, understanding these stakeholders is essential to understanding their mental model, cultural biases, and tacit expectations of a new system (Dearden, 2008; MAGUIRE, 2001; Norman & Draper, 1986). Further, given mHealth systems will involve significant new practices for these HCWs (e.g., Florez-Arango et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2013; Vélez et al., 2014), it is important for scholars and designers to understand the existing practices users may already have in place (Bødker, 2000; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2006).

Fourth, this study found that, although the role of patients is generally well researched, there is a significant oversight in terms of the design and analysis of system-relevant patient-to-patient interactions. This is a significant shortcoming for the body of knowledge around mHealth, as peer-based observation, discussion, and referral plays an important role when introducing new systems (Jasperson, Carter, & Zmud, 2005; Lou, Chau, & Li, 2005). One of the three papers that studied this stakeholder interaction (Chang et al., 2011) suggests this is equally relevant for mHealth systems in rural areas of developing countries, demonstrating that when patients are trained to care for other patients it brings support to others through peer-based exchange of information and counselling.

Fifth, but perhaps most importantly, analysis of existing literature revealed a significant under representation of research studying system developers’ interactions. Recent advances in system design have shown that the manner in which system developers interact with potential users is key to eliciting good requirements, spotting issues early, and allowing creative solutions to be presented for complex situated problems (Brown, 2008; Brown & Wyatt, 2010; Buchanan, 1992). Thus, this under-representation may be limiting the effectiveness of mHealth initiatives by inadvertently creating design contexts where system developers have limited capacity to empathise with patients and Health care Workers. The interactions between system developers highlighted the collaborative viability of using an open-source mobile platform specifically designed for use in low-resource settings by mHealth implementers to conduct data collection (e.g., DeRenzi et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2013; Rajput et al., 2012; van Dam et al., 2017). Researchers believe collaborative approaches to system development would encourage mHealth implementers to adopt accepted standards and interoperable technologies, preferably using open-source architecture, making it cost-effective to everyone (e.g., Hufnagel, 2012; Kay et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2013; Rajput et al., 2012; Woodward & Woodward, 2016).

Sixth, this study found that most of the mHealth interventions took place in African Countries, constituting about 65% of the sampled papers with variations among countries by mHealth type. This may be due in part to the fact that most African countries are lagging behind the rest of the world regarding health care access (Barber et al., 2017). Most of these initiatives in the sampled data are either funded by private–public partnerships, or NGO’s and oversea initiatives (Woodward & Woodward, 2016). Approximately 26% of the sampled papers were from Asian Countries. The Americas constitute about 9% of the sampled papers. There were few interventions measuring quality clinical outcomes but a considerable number of the sampled literature were explicit on the processes undertaken and with high level of satisfaction expressed by both patients and Health care Workers alike (e.g., Adedokun et al., 2016; Leon et al., 2015; Nhavoto et al., 2017).

Based on these findings, we thus call for future research that focuses specifically on the interaction between system developers and other stakeholders. Further, we call for research that delves into the critical peer-based information exchange, referral, and knowledge sharing that happens between Patients, either as a result of new mHealth initiatives, or those interactions that may impede new developments. The importance of understanding cultural variation in the analysis and design of IT systems is long documented (e.g., Avgerou, 2008; Reinecke & Bernstein, 2013; Walsham, 2002; Walsham & Sahay, 2006). Addressing these gaps will be crucial to increasing cultural sensitivity and allowing mHealth systems to reach the poorest and most remote regions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adedokun, A. , Idris, O. , & Odujoko, T. (2016). Patients’ willingness to utilize a SMS-based appointment scheduling system at a family practice unit in a developing country. Primary Health Care Research & Development , 17(2), 149–156. 10.1017/S1463423615000213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afridi, M. J. , & Farooq, M. (2011). OG-miner: An intelligent health tool for achieving millennium development goals (MDGs) in m-health environments. Paper presented at the 2011 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS) 1–10, Hawaii. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, N. K. (2012). Applying mobile technologies to mental health service delivery in South Asia. Asian Journal of Psychiatry , 5(3), 225–230. 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.-H. , & Skudlark, A. E. (1997). Resolving conflict of interests in the process of an information system implementation for advanced telecommunication services. Journal of Information Technology , 12(1), 3–13. 10.1080/026839697345170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajay, V. S. , & Prabhakaran, D. (2011). The scope of cell phones in diabetes management in developing country health care settings. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology , 5(3), 778–783. 10.1177/193229681100500332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akter, S. , Ray, P. , & D’Ambra, J. (2013). Continuance of mHealth services at the bottom of the pyramid: The roles of service quality and trust. Electronic Markets , 23(1), 29–47. 10.1007/s12525-012-0091-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M. , Khanam, T. , & Khan, R. (2010). Assessing the scope for use of mobile based solution to improve maternal and child health in Bangladesh: A case study. Paper presented at the International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ansoff, H. (1965). Igor: Corporate strategy. New York, NY : McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, K. , Liu, F. , Seymour, A. , Mazhani, L. , Littman-Quinn, R. , Fontelo, P. , & Kovarik, C. (2012). Evaluation of txt2MEDLINE and development of short messaging service–optimized, clinical practice guidelines in Botswana. Telemedicine and e-Health , 18(1), 14–17. 10.1089/tmj.2011.0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asangansi, I. , & Braa, K. (2010). The emergence of mobile-supported national health information systems in developing countries. Studies in Health Technology Informatics , 160(Pt 1), 540–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashar, R. , Lewis, S. , Blazes, D. L. , & Chretien, J.-P. (2010). Applying information and communications technologies to collect health data from remote settings: A systematic assessment of current technologies. Journal of Biomedical Informatics , 43(2), 332–341. 10.1016/j.jbi.2009.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avgerou, C. (2008). Information systems in developing countries: A critical research review. Journal of Information Technology , 23(3), 133–146. 10.1057/palgrave.jit.2000136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailur, S. (2006). Using stakeholder theory to analyze telecenter projects. Information Technologies & International Development , 3(3), 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bakibinga, P. , Kamande, E. , Omuya, M. , Ziraba, A. K. , & Kyobutungi, C. (2017). The role of a decision-support smartphone application in enhancing community health volunteers’ effectiveness to improve maternal and newborn outcomes in Nairobi, Kenya: Quasi-experimental research protocol. BMJ Open , 7(7), e014896. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi, A. , Narasimhan, P. , Li, J. , Chernih, N. , Ray, P. K. , & MacIntyre, R. (2011). mHealth for the control of TB/HIV in developing countries. Paper presented at the e-Health Networking Applications and Services (Healthcom), 2011 13th IEEE International Conference, Columbia, MO. 10.1109/HEALTH.2011.6026797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, R. , Gopichandran, V. , Chaturvedi, S. , Chatterjee, R. , Mahapatra, T. , & Chaudhuri, I. (2016). Continuum of Care Services for Maternal and Child Health using mobile technology–a health system strengthening strategy in low and middle income countries. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making , 16(1), 84. 10.1186/s12911-016-0326-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber, R. M. , Fullman, N. , Sorensen, R. J. , Bollyky, T. , McKee, M. , Nolte, E. , … Abbas, K. M. (2017). Healthcare Access and Quality Index based on mortality from causes amenable to personal health care in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: A Novel Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 . Lancet , 390(10091), 231–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bediang, G. , Stoll, B. , Elia, N. , Abena, J.-L. , Nolna, D. , Chastonay, P. , & Geissbuhler, A. (2014). SMS reminders to improve the tuberculosis cure rate in developing countries (TB-SMS Cameroon): A protocol of a randomised control study. Trials , 15(1), 35. 10.1186/1745-6215-15-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigna, J. J. R. , Noubiap, J. J. N. , Kouanfack, C. , Plottel, C. S. , & Koulla-Shiro, S. (2014). Effect of mobile phone reminders on follow-up medical care of children exposed to or infected with HIV in Cameroon (MORE CARE): A multicentre, single-blind, factorial, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases , 14(7), 600–608. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70741-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bødker, S. (2000). Scenarios in user-centred design – setting the stage for reflection and action. Interacting with Computers , 13(1), 61–75. 10.1016/S0953-5438(00)00024-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourouis, A. , Zerdazi, A. , Feham, M. , & Bouchachia, A. (2013). M-health: Skin disease analysis system using smartphone’s camera. Procedia Computer Science , 19, 1116–1120. 10.1016/j.procs.2013.06.157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review , 86(6), 84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. , & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. development outreach (pp. 31–35). World Bank. © World Bank. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6068 [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked problems in design thinking. Design Issues , 8(2), 5–21. 10.2307/1511637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busis, N. (2010). Mobile phones to improve the practice of neurology. Neurologic Clinics , 28(2), 395–410. 10.1016/j.ncl.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A. B. , & Näsi, J. (1997). Understanding stakeholder thinking: Themes from a finnish conference. Business Ethics: A European Review , 6(1), 46–51. 10.1111/beer.1997.6.issue-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, P. S. , Sowmya, H. , Mehrotra, S. , & Duggal, M. (2014). ‘SMS’ for mental health–Feasibility and acceptability of using text messages for mental health promotion among young women from urban low income settings in India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry , 11, 59–64. 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L. W. , Kagaayi, J. , Arem, H. , Nakigozi, G. , Ssempijja, V. , Serwadda, D. , … Reynolds, S. J. (2011). Impact of a mHealth intervention for peer health workers on AIDS care in rural Uganda: A mixed methods evaluation of a cluster-randomized trial. AIDS and Behavior , 15(8), 1776–1784. 10.1007/s10461-011-9995-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L. W. , Njie-Carr, V. , Kalenge, S. , Kelly, J. F. , Bollinger, R. C. , & Alamo-Talisuna, S. (2013). Perceptions and acceptability of mHealth interventions for improving patient care at a community-based HIV/AIDS clinic in Uganda: A mixed methods study. AIDS Care , 25(7), 874–880. 10.1080/09540121.2013.774315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chib, A. (2010). The Aceh Besar midwives with mobile phones project: Design and evaluation perspectives using the information and communication technologies for healthcare development model. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 15(3), 500–525. 10.1111/(ISSN)1083-6101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chib, A. , & Chen, V. H.-H. (2011). Midwives with mobiles: A dialectical perspective on gender arising from technology introduction in rural Indonesia. New Media & Society , 13(3), 486–501. 10.1177/1461444810393902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chib, A. , van Velthoven, M. H. , & Car, J. (2015). mHealth adoption in low-resource environments: A review of the use of mobile healthcare in developing countries. Journal of Health Communication , 20(1), 4–34. 10.1080/10810730.2013.864735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chib, A. , Wilkin, H. , & Hoefman, B. (2013). Vulnerabilities in mHealth implementation: A Ugandan HIV/AIDS SMS campaign. Global Health Promotion , 20(suppl 1), 26–32. 10.1177/1757975912462419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chib, A. , Wilkin, H. , Ling, L. X. , Hoefman, B. , & Van Biejma, H. (2012). You have an important message! evaluating the effectiveness of a text message HIV/AIDS campaign in northwest Uganda. Journal of Health Communication , 17(supp 1), 146–157. 10.1080/10810730.2011.649104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, M. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review , 20(1), 92–117. [Google Scholar]

- Craven, M. P. , Lang, A. R. , & Martin, J. L. (2014). Developing mHealth apps with researchers: Multi-stakeholder design considerations. In Craven M. P. (Ed.), Design, user experience, and usability. User experience design for everyday life applications and services. DUXU 2014. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Vol. 8519, pp. 15–24). Cham: Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-07635-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dammert, A. C. , Galdo, J. C. , & Galdo, V. (2014). Preventing dengue through mobile phones: Evidence from a field experiment in Peru. Journal of Health Economics. , 35, 147–161. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis, C. M. , Ellis, J. B. , Kellogg, W. A. , van Beijma, H. , Hoefman, B. , Daniels, S. D. , & Loggers, J.-W. (2010). Mobile phones for health education in the developing world: SMS as a user interface. Proceedings of the First ACM Symposium on Computing for Development , 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dearden, A. (2008). User-centered design considered harmful (with apologies to Edsger Dijkstra, Niklaus Wirth, and Don Norman). Information Technologies & International Development , 4(3), 7–12. 10.1162/itid.2008.4.issue-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeRenzi, B. , Borriello, G. , Jackson, J. , Kumar, V. S. , Parikh, T. S. , Virk, P. , & Lesh, N. (2011). Mobile phone tools for field-based health care workers in low-income countries. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine: A Journal of Translational and Personalized Medicine , 78(3), 406–418. 10.1002/msj.v78.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeStigter, K. (2012). mHealth and developing countries: A successful obstetric care model in Uganda. Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology , 46(s2), 41–44. 10.2345/0899-8205-46.s2.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Canseco, F. , Zavala-Loayza, J. A. , Beratarrechea, A. , Kanter, R. , Ramirez-Zea, M. , Rubinstein, A. , & Miranda, J. J. (2015). Design and multi-country validation of text messages for an mHealth intervention for primary prevention of progression to hypertension in Latin America. JMIR mHealth and uHealth , 3(1), e19. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T. , & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review , 20(1), 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Elms, H. , Berman, S. , & Wicks, A. C. (2002). Ethics and incentives: An evaluation and development of stakeholder theory in the health care industry. Business Ethics Quarterly , 12(4), 413–432. 10.2307/3857993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]