Abstract

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) which is caused by feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), a variant of feline coronavirus (FCoV), is a member of family Coronaviridae, together with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and SARS-CoV-2. So far, neither effective vaccines nor approved antiviral therapeutics are currently available for the treatment of FIPV infection. Both human and animal CoVs shares similar functional proteins, particularly the 3CL protease (3CLpro), which plays the pivotal role on viral replication. We investigated the potential drug-liked compounds and their inhibitory interaction on the 3CLpro active sites of CoVs by the structural-bases virtual screening. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay revealed that three out of twenty-eight compounds could hamper FIPV 3CLpro activities with IC50 of 3.57 ± 0.36 μM to 25.90 ± 1.40 μM, and Ki values of 2.04 ± 0.08 to 15.21 ± 1.76 μM, respectively. Evaluation of antiviral activity using cell-based assay showed that NSC629301 and NSC71097 could strongly inhibit the cytopathic effect and also reduced replication of FIPV in CRFK cells in all examined conditions with the low range of EC50 (6.11 ± 1.90 to 7.75 ± 0.48 μM and 1.99 ± 0.30 to 4.03 ± 0.60 μM, respectively), less than those of ribavirin and lopinavir. Analysis of FIPV 3CLpro-ligand interaction demonstrated that the selected compounds reacted to the crucial residues (His41 and Cys144) of catalytic dyad. Our investigations provide a fundamental knowledge for the further development of antiviral agents and increase the number of anti-CoV agent pools for feline coronavirus and other related CoVs.

Keywords: Small molecules, Virtual screening, Feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIP), Antiviral activity, CoVs surrogate

Highlights

-

•

Virtual screening and molecular docking revealed three lead compounds bound to FIPV 3CLpro active site.

-

•

The 3D structures of 3CLpro of coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-2 are highly conserved.

-

•

These compounds showed inhibitory effects on the proteases of FIPV, PEDV, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.

-

•

Their antiviral activities are better than Ribavirin and Lopinavir while comparable to GC376.

1. Introduction

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), which is caused by feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), is a life threatening, immunopathogenic disease affecting multiple organs in cats (Pedersen, 2014). FIPV is a variant of feline coronavirus (FCoV) that infects enterocytes and produces only mild enteritis in cats. FIPV is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the family Coronaviridae which includes also severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and SARS-CoV-2. Up to date, no effective vaccine or antiviral drugs is available for FIPV treatment. Available antiviral agents for viral infection in companion animals; particularly cats, are those widely used in humans, which could interfere different stages of viral infection (Wilkes and Hartmann, 2016; Pedersen, 2014; Sykes and Papich, 2013). Antiviral drugs for feline herpesvirus and retroviruses, mostly nucleoside analogues, are not always safe in cat therapy due to adverse effects relating to their toxicity. Antiviral agents in animals should inhibit specifically to viral multiplication without affecting normal host cells and possess a good potency and bioavailability.

Regarding to viral characteristics, all members of the family Coronaviridae including the genus Alphacoronavirus [feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV)] and the genus Betacoronavirus (SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2) possess similar genome organization and share the same features of the functional structural or non-structural viral proteins. In a viral replication cycle, the two polyproteins (pp1a and pp1ab), encoded by two open reading frames (ORF1a and ORF1b), are commonly cleaved by viral proteases including 3C-like protease (3CLpro, also called main protease) into 16 non-structural proteins. 3CLpro is the main protease sharing common characteristics with a typical chymotrypsin (-like) viral protease, 3Cpro or 3CLpro, in the picornavirus-like supercluster (Kim et al., 2012). The 3CLpro catalytic dyad contains two crucial residues, His41 and Cys144 for FIPV; His41 and Cys145 for SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2; and His41-Cys148 for MERS-CoV, which the cysteine residue acts as a nucleophile (Jin et al., 2020; Galasiti Kankanamalage et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2016; Hsu et al., 2005). The substrate-binding site of proteases could serve as a starting point for antiviral drug design.

The novel emerging coronavirus officially named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that causes the COVID-19 pandemic crisis has accelerated the development and testing of several potential therapeutics including the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs to promptly obtain effective antiviral drugs against the virus. Some FDA-approved drugs have been currently used or reached the clinical trials for COVID-19 patient treatment, such as HIV protease inhibitor (e.g. lopinavir/ritonavir), or antimalarial drug (hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine), which could substantially decrease severity and/or duration of the disease (Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines, 2020). However, on July 4, 2020, WHO has recently announced to discontinue hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir, since these drugs could not reduce the mortality of COVID-19 patients when compare to a standard-of-care (Cao et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). The FDA issue an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) has authorized remdesivir for severe COVID-19 treatment based on the potential benefits from the randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials (Beigel et al., 2020; Grein et al., 2020). Additionally, it should be noted that RNA viruses naturally possess rapid mutation characteristics leading to swift evolution of drug resistant strains. Therefore, at this moment, searching for novel potential antiviral compounds for CoVs is still essential to be applied as single or combination therapeutics regimen to relief the clinical symptoms and lessen the viral spreading.

In vitro cell-based screening for antiviral agents for SARS-CoV-2 is limited only in high containment biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) laboratories (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020), which require costly operation and maintenance. However, FIPV is classified as risk group II pathogens which can cause a disease in human or animals but are unlikely to be a serious hazard to laboratory workers, the community, livestock, or the environment. Therefore, handling and examining FIPV can be performed in a BSL-2 laboratory based on biosafety classification of the U.S. Public Health Service Guidelines (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Furthermore, using FIPV as a surrogate for the high hazardous CoVs will also minimize the exposure risk of laboratory staffs and minimize the testing cost.

We have utilized molecular docking approach for screening the available chemical libraries from the public compound libraries sources. This approach could accelerate the searching for potential compounds, while minimize the times and investment of the pharmaceutical industry. In the present study, we aimed to identify the chemical compounds that can bind to the active site of FIPV 3CLpro by the structural-bases virtual screening using docking software and determining their antiviral activities using the inhibitory enzymatic and the cell-based assays. This study also presented that FIPV can be exploited as a surrogate platform to screen for viral inhibitors including anti-3CLpro which is the upstream process of anti-CoV drug discovery.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Virtual screening using in silico docking and compound libraries

Three dimension structures of CoVs-3CLpro were prepared based on public available Protein Data Bank (PDB) using crystal structures [FIPV PDB: 5EU8 (Wang et al., 2016), TGEV:2AMP (Yang et al., 2005), PEDV:5GWZ (Wang et al., 2017), SARS-CoV:1Z1I (Hsu et al., 2005), MERS-CoV:5WKM (Galasiti Kankanamalage et al., 2018) and SARS-CoV-2:6LU7 (Jin et al., 2020)] for the initial coordinates of virtual screening. The initially available 6409 compounds from NCI/DTP Open Chemical Repository (http://dtp.cancer.gov) including Diversity Sets (III, IV and V) and Mechanical Sets (II and III) were retrieved for virtual screening with the FIPV 3CLpro binding pocket. The 2D structures of the compounds were generated by coordinating to their 3D structures before docking on the enzyme active site using Open Babel (O'Boyle et al., 2011). Initial molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina (Trott and Olson, 2010), which based on Lamarckian Generic Algorithm (GA). The default parameters were set at 20 GA runs, individuals in the population, 270,000 maximum numbers of energy evaluation and 0.02 gene mutation rate and 0.8 crossover rate. The input file was converted to the pdbqt format. The grid center (X:Y:Z) and grid dimension (X:Y:Z) were arranged as described previously (Theerawatanasirikul et al., 2020), which facilitated the preferential binding to Cys and His residues within the catalytic dyad. The outputs of ten docking poses for each compound were generated. In addition, the compounds with 3CLpro binding affinity scores less than −5.0 kcal/mol that passed the criteria of Lipinski's rule of five (Lipinski, 2004) were selected. The interactions of the candidate protein–ligand complexes—mostly non-covalent—were stored for further evaluation of protein–ligand interaction using LigPlot version 1.4.5. (Laskowski and Swindells, 2011), and the Discovery Studio Visualizer version 17.2.0 (Dassault Systemes Biovia Corp).

2.2. FIPV 3CL protease construction and expression

The gene encoding of FIPV 3CLpro was amplified from viral genome of FIPV II strain 79-1146 (ATCC, VR990) by using RT-PCR with the forward primer 5′-CAT GCC ATG GCT ATC GAG GGA AGG TCC GGA TTG AGA AAA ATG GCA C-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CCG CTC GAG TTA CTG AAG ATT AAC ACC ATA CAT TTG C- 3’. The purified PCR products were cloned into pET32a vector. The thioredoxin-tag (Trx-tag), His-tag and the FXa cleavage site (IEGR) were placed in order at N-terminus of the 3CLpro ORF. Then, vector pET-32a were excised with NcoI and XhoI restriction enzymes. The plasmid containing full and correct sequence of FIPV 3CLpro was subsequently transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) for protein expression. The expressed protein was digested with Factor Xa protease and then loaded onto another Ni-NTA column (GE Healthcare Bio-Science AB, Uppsala, Sweden) to remove the thioredoxin and hexa-His tag. The tag-free FIPV 3CLpro with no extra residues at the N-terminus was analyzed by SDS-PAGE as previously described (Theerawatanasirikul et al., 2020).

2.3. In vitro protease inhibition using FRET assay

In vitro protease inhibition assay were performed as described elsewhere in a 96-well black plate (Kuo et al., 2004). Each well of the enzyme reaction mixture contained 100 μl of 35 nM FIPV 3CLpro, 6 μM fluorogenic substrate peptide (Dabcyl-KTSAVLQSGFRKME-Edans) in a reaction buffer (25 mM Bis-Tris pH 7.0). The various concentrations of each compound and the enzyme reaction mixture were incubated for 10 min at room temperature before addition of the substrate peptide. Enhanced fluorescence due to cleavage of the fluorogenic substrate was recorded every 20 s for 30 min at 355 nm excitation and 538 nm emission using a fluorescence plate reader (BMG FLUOstar OPTIMA Microplate Reader, Ortenberg, Germany). The relative reduction of protease activity of each compound was calculated to obtain concentrations of the compounds that can inhibit 50% of the protease activity (IC50). To obtain the enzyme activities, the compounds were fixed at two concentrations and examined with various substrate concentrations—0, 3, 6, 10 and 20 μM—in a reaction mixture containing 35 nM FIPV 3CLpro. Ki values of the compounds were plotted, and the enzyme kinetics was calculated using Lineweaver–Burk equation. The data were analyzed by non-linear regression using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (Prism, San Diego, USA). Ribavirin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), Lopinavir (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and GC-376 (Target Molecule Corp., USA) were used as positive controls.

2.4. Cells and viruses

Cell culture and virus propagation were performed as describe previously (Theerawatanasirikul et al., 2020). Crandell-Rees feline kidney (CRFK) cell line (ATCC, CCL-94) was maintained in Modified Eagle Medium (MEM, Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, USA), supplemented with 7% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen™ Carlsbad, USA) and antibiotics-antimycotics (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, USA). FIPV strain 79-1146 (ATCC, VR-990) was propagated in CRFK cell line with minimum supplement with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, USA) and 1% antibiotics-antimycotics (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, USA) at 37 °C with 5%CO2 for 48 h. The cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed daily under an inverted microscope (Olympus CKX41, Tokyo, Japan). After the fifth passages of viral propagation, the virus stock was quantitated as decribed previously (Lekcharoensuk et al., 2012), and the virus titer was 107 TCID50/ml. The virus stock was kept at −80 °C for further experiments.

2.5. In vitro cytotoxicity assay

CRFK cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/ml onto the 96-well plate and incubated overnight. The compounds were dissolved in DMSO to prepared stock solution at 10 mM, which were further diluted in the culture media to generate various concentrations (200, 100, 10, 1 and 0.1 μM). The cells were incubated with the compounds at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 48 and 72 h. Each treatment was performed in triplicates. To measure the cell viability, 20 μl of MTS reagent (CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay Kits, Promega®, Madison, USA) was added into each culture well and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h according to the manufacturer's instruction. The optical density (OD) of the tested samples was analyzed by spectrophotometer at A 490 nm (BioTeK® microplate reader, USA). Dose-response curves were plotted. The compound concentration that causes 50% cell death, so called 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50), was determined by non-linear regression using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (Prism, San Diego, USA).

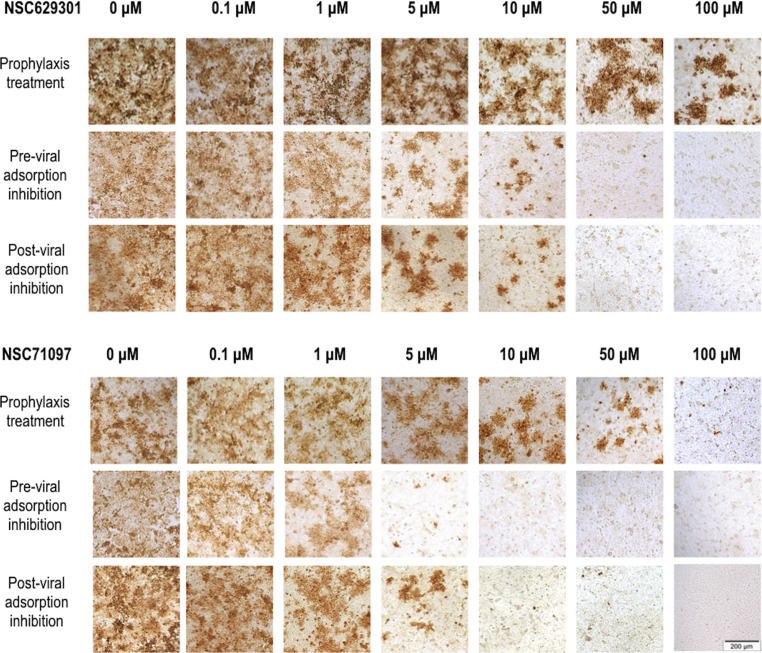

2.6. Antiviral activity of compounds in cell culture

The CRFK cells were seeded overnight at 1 × 105 cells/ml (100 μl/well) onto a 96-well plate to determine viral infection by immunoperoxidase monolayer assay (IPMA) and at 5 × 104 cells/well (250 μl/well) onto 24-well plates for viral quantification by RT-qPCR. The experiments were done in triplicates, and each set was composed of three conditions; prophylaxis treatment, pre-viral absorption inhibition and post-viral absorption inhibition. For the prophylaxis treatment, a serial dilution of each compound was incubated onto a monolayer of confluent CRFK cells at 37 °C for 2 h. The cells were then washed twice with PBS before inoculated with FIPV at 100 TCID50. The inoculated CRFK cells were further incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. In the pre-viral adsorption inhibition experiment, different concentrations (200, 100, 50, 20, 10, 1 and 0.1 μM) of each compound was added onto the CRFK cells, and the cells were then immediately inoculated with 100 TCID50 of FIPV at 37 °C for 24 h. For the post-viral absorption inhibition experiment, the CRFK cells were incubated with 100 TCID50 of FIPV at 37 °C for 2 h to allow viral adsorption. The infected cells were then treated with a serial dilution of each compound. In all three conditions, the compound treated, virus infected cells were inoculated for 24 h and CPE was observed in each well. The virus- and mock-infected CRFK cell controls were also included in every experiment. DMSO (1%) was added onto the mock- and virus-infected cells as non-inhibitor controls. FIPV antigens in the CRFK cells in 96-well plate were detected using immunoperoxidase monolayer assay (IPMA). The other set of cells in 24-well plate were also prepared as described above for viral quantification. The viruses were harvested by 2 freezing-thawing cycles and the virus suspension were quantified using quantitative real-time RT-PCR (RT-qRCR).

2.7. FIPV antigens detection using IPMA

The FIPV infected CRFK cells with or without the compound treatment were fixed using cold methanol at room temperature for 30 min, then dried and stored at −20 °C before staining by IPMA (Lekcharoensuk et al., 2012). The fixed cells were blocked with 2% BSA in PBS. The cells were incubated with primary antibody (mouse anti-FIPV3-70, dilution 1:500, ThermoFisher, Carlsbad, USA) at 37 °C for 1 h. After a rinse with PBS, cells were incubated with secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP, dilution 1:400, Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Madison, USA) at 37 °C for 1 h, and antigen-antibody reaction was visualized after adding DAB substrate (DAKO, Santa Clara, USA). The infected cells were stained and the positive signal would be dark brown. The cells were viewed under an inverted microscope (Olympus CKX41, Tokyo, Japan) at magnification of × 100. The 50% effective concentration (EC50) was evaluated from the ratio of areas between the stained positive cells and unstained cells in the infected CRFK wells by our developed pipeline (Theerawatanasirikul et al., 2020) using the CellProfiler software version 3.1.9 (Broad Institute; freeware available at http://www.cellprofiler.org/index.htm).

2.8. FIPV RNA quantification using RT-qPCR

To determine the effects of the candidate compounds on FIPV replication, the FIPV genomic RNA copies were quantified using RT-qPCR. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from the harvested FIPV using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, USA), and then the RNA samples were reverse transcribed into cDNA with SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, USA). The sequences of the primers specific to FCoV viral genome are 5′–GGC AAC CCG ATG TTT AAA ACT GG–3’ (forward) and 5′–CAC TAG ATC CAG ACG TTA GCT C–3’ (reverse) (Herrewegh et al., 1995; Manasateinkij et al., 2009). The 10 μl qPCR reaction contained 5 μl SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (2 × ) (Bio-Rad, USA), 4 μl template cDNA and 0.5 μl of each primer. The cycling condition are as follows: initial denaturation of DNA at 95 °C for 30 s, 30 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C of denaturation and 5 s at 60 °C of annealing and extension, and followed by a melting curve analysis from 65 to 95 °C with 0.5 °C increment. The qPCR was carried out by including the two biological and three technical replications. For absolute quantitation of the viral copies, a standard curve was established with a ten-fold serial dilution (10−2 to 10−7) of plasmid containing FIP 3′-UTR sequence.

2.9. Statistical analysis of an effective concentration

Data from the image analysis were calculated, and a half of effective concentration (EC50) of each compound was evaluated using non-linear regression (GraphPad version 8.0, Prism, San Diego, USA). Both IPMA and real-time qPCR viral detections were tested in duplicates and three independent experiments. The EC50 values of IPMA results were presented as means and standard deviation, and qPCR data were analyzed and reported as the percentage of viral reduction for each compound. Selectivity Index (SI) was determined as the ratio of CC50 to EC50 for each compound.

3. Results

3.1. Virtual screening of the compound targeting FIPV 3CLpro

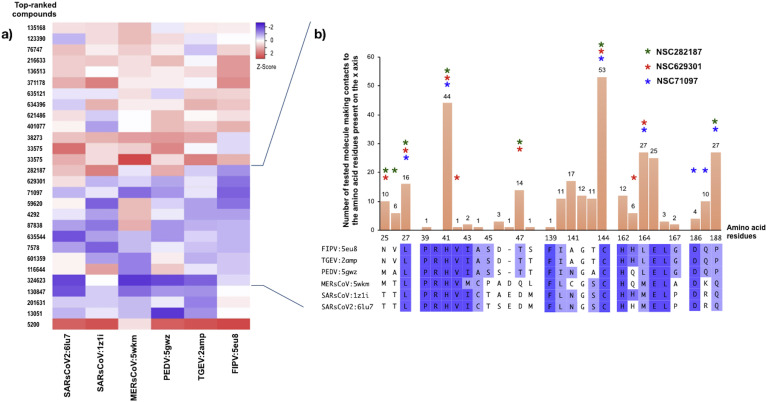

In this study, the structural based virtual screening was performed in which the compounds were placed within the binding pocket of the 3CLpro due to high similarity of amino acid residues among various CoVs. Then, the most favorable binding energies between the compounds and the catalytic dyads within the binding pocket of CoVs-3CLpro were analized. The binding affinity scores of the 28 top-ranked compounds and CoVs-3CLpro structure were ranged from −8.7 to −5.2 kcal/mol. These 28 top-ranked compounds were selected and re-scored again using AutoDock Vina. The binding affinity scores of complexes between ligands and the 3CLpro of all CoVs were transformed to z-scores and used to create a correlation mapping by the average linkage method according to Heatmapper server (Babicki et al., 2016).

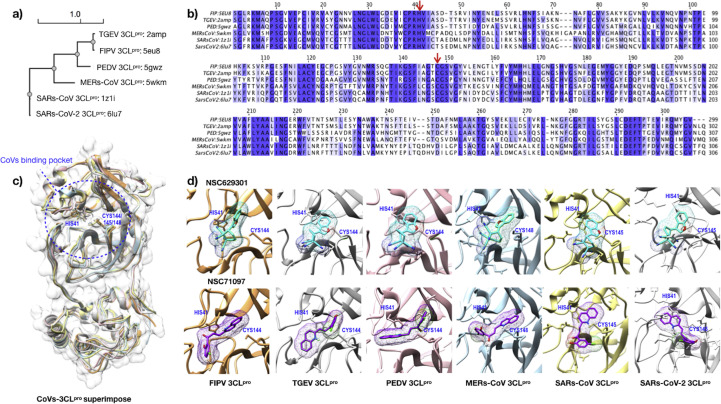

The phylogenetic analysis of the 3CLpro of FIPV amino acid sequences showed that the FIPV 3CLpro was closed to that of TGEV and shared superclustering with 3CLpro of PEDV, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The multiple sequence alignment of amino acid sequences of CoVs-3CLpro revealed the relatively conserved residues (Supplementary Fig. 1b). When their 3D structures were superimposed, these conserved residues are in the vicinity of the catalytic dyads (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

The 3D structures of 3CLpro from alphacoronaviruses (TGEV:2AMP, and PEDV:5GWZ), and betacoronaviruses (SARS-CoV:1Z1I, MERS-CoV:5WKM and the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2:6LU7) were evaluated. Values of the binding affinities between the compounds and CoVs-3CLpro were presented as a heatmap (Fig. 1 a). The eleven top-ranked compounds bound to FIPV 3CLpro were selected to annotate the active sites of all CoVs, which their 3D structures were highly conserved especially at His41 and Cys144/145/148 numbering based on the positions on the FIPV 3CLpro structure (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1b–d). Molecular docking and sequence analysis of other CoVs-3CLpro in respect to the FIPV 3CLpro sequence exhibits highly conserved amino acid residues (Leu27, Pro39, Val42, Phe139, Cys144, His162, Glu165, Leu166 and Asp186) in the catalytic dyad which strongly interact with the candidate compounds (Supplementary Fig. 1d). These results indicates that FIPV 3CLpro has a potential use as a surrogate platform to screen the candidate compounds that could inhibit the CoVs-3CLpro activities.

Fig. 1.

Heatmap displaying the binding affinities of the best 28 top-ranked compounds (y-axis) and protease active sites in the PDB structures of various coronaviruses (x-axis) (a). The values were normalized by transforming the binding energies to z-score prior to creating a heatmap and clustering by using the average linkage. The shed color schemes were assigned based on the transformed data, which ranged from strong (purple), moderate (white) to weak (red) binding affinities, respectively. The structural interactions for all contacts of CoVs-3CLpro docking complexes were analyzed with the best 11 top-ranked compounds of FIPV 3CLpro (b, upper panel) by Heatmapper (http://www.heatmapper.ca/). Each solid bar presents the number of small molecules making contacts (y-axis) to each amino acid residue (x-axis). The residues within the binding pocket of FIPV 3CLpro that interact directly with NSC282187, NSC629301, and NSC71097 are marked with asterisks. The alignment of the contacting amino acid residues of CoVs-3CLpro with the selected compounds were compared and the purple gradient colors present the amino acid similarity among CoVs (b, lower panel).

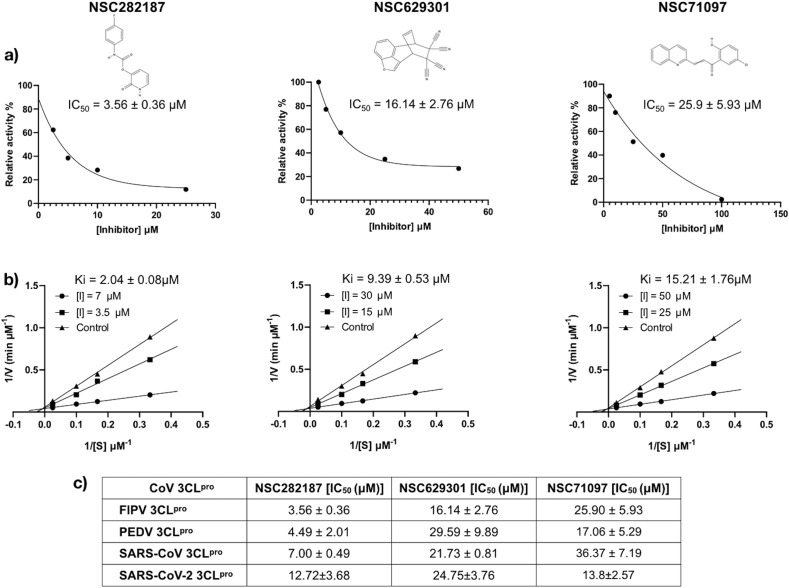

3.2. Protease inhibition using FRET assay

According to the FIPV 3CLpro structural based study, we determined if the candidate compounds that could bind to the active site and inhibited the protease activity still actively impeded the viral growth in cell culture. The candidate compounds possessing the inhibitory effect on protease activity had IC50 values of 3.57 ± 0.36 μM (NSC282187), 16.14 ± 2.76 μM (NSC629301), and 25.90 ± 5.93 μM (NSC71097), whereas IC50 of GC-376 (FIPV 3CLpro inhibitor) was 0.18 ± 0.02 μM as shown in Table 1 . The Ki values of NSC282187, NSC629301 and NSC71097 were 2.04 ± 0.08, 9.39 ± 0.53, and 15.21 ± 1.76 μM, respectively (Fig. 2 ). In addition, the protease inhibition assay of PEDV 3CLpro, SARS-CoV 3CLpro, and SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro was also performed and the inhibition results are corresponding to that of FIPV 3CLpro (Fig. 2c).

Table 1.

The IC50, CC50, EC50 and the selectivity indices (SI) of the candidate compounds evaluated by protease inhibition and cell-based assays.

| Compound ID | Cell-based assay |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% inhibitory concentration IC50 (μM)a | 50% cytotoxic concentration CC50 (μM)b | Prophylaxis treatment (EC50; μM)c |

Pre-viral adsorption inhibition (EC50; μM)d |

Post-viral adsorption inhibition (EC50; μM)e |

||||

| IPMA | SI | IPMA | SI | IPMA | SI | |||

| NSC282187 | 3.57 ± 0.36 | 510.70 ± 0.13 | >200 | N/A | >100 | N/A | >100 | N/A |

| NSC629301 | 16.14 ± 2.76 | 23.18 ± 5.19 | 6.11 ± 1.90 | 2.17 | 7.75 ± 0.48 | 1.71 | 6.20 ± 0.88 | 2.14 |

| NSC71097 | 25.90 ± 5.93 | 68.47 ± 4.82 | 1.99 ± 0.30 | 3.69 | 4.03 ± 0.60 | 7.40 | 2.34 ± 0.96 | 2.21 |

| Ribavirin | ND | >500 | >200 | N/A | 51.54 ± 1.52 | 24.33 | 74.60 ± 1.75 | 16.81 |

| Lopinavir | 224.81 ± 43.90 | >100 | 33.74 ± 1.53 | >2.96 | 8.56 ± 0.79 | >11.68 | 6.22 ± 0.34 | >16.07 |

| GC376 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | >200 | 1.30 ± 0.13 | >153.84 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | >555.55 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | >338.98 |

The fifty percent of effective concentration (EC50) was determined by three independent cell-based assays using IPMA assays; Selective index (SI) = CC50/EC50.

ND not determined.

Fifty percent of inhibition concentration (IC50) by protease inhibitory assay.

Fifty percent of cytotoxic concentration (CC50) by MTS assay.

Pre-treatment with the selected compounds at 37 °C for 2 h before adding FIPV inoculum at 100 TCID50/well.

FIPV inoculum at 100 TCID50/well with the selected compounds.

FIPV inoculum at 100 TCID50/well at 37 °C for 2 h before adding the selected compounds with further incubation.

Fig. 2.

FRET-based protease assay. Enzyme kinetics of the three hits against FIPV 3CLpro activities using dose-response curves (a) with respect to the substrate peptide (Dabcyl-KTSAVLQSGFRKME-Edans). The Lineweaver–Burk plots of the determined Ki values of NSC282187, NSC629301, and NSC71097, respectively, (b) using different concentrations of the substrates. The IC50s of FIPV 3CLpro, PEDV 3CLpro, SARS-CoV 3CLpro and SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro were shown as means and SDs.

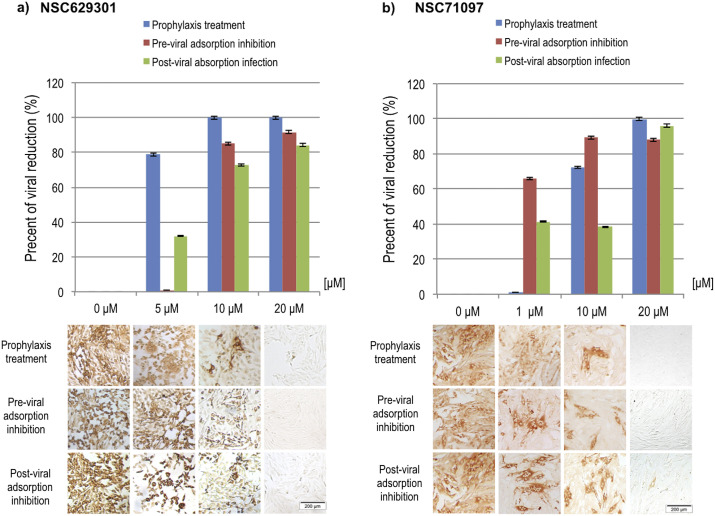

3.3. Cytotoxicity and an cell based antiviral efficacy of the selected compounds

After screening using in silico and in vitro protease assay, the three selected compounds were further examined for their cytotoxicity. The results showed that compound NSC282187 had no effect on the CRFK cells even though at the concentration as high as 510.70 μM, whereas the CC50 values of NSC629301 and NSC71097 were 28.13 ± 5.19 μM and 68.47 ± 4.82 μM, respectively (Table 1).

The antiviral activity was assessed using IPMA to determine the effective concentration (EC50) of the compounds against FIPV infectivity as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3 . The prophylaxis experiment was designed to allow the entry of small compounds into the host cells, and also determined that the compounds remaining in the supernatant still had a sufficient viral inhibition potency. We found that compounds NSC629301 and NSC71097 had inhibitory effect on FIPV with EC50 = 6.11 ± 1.90 μM and 1.99 ± 0.30 μM, respectively. Although, the protease inhibitory assay showed that NSC282187 could strongly inhibit FIPV 3CLpro activity with very low Ki value (Fig. 2), the compound NSC282187 did not show antiviral activity in the FIPV infected cells. It is possible that the compound could not pass the cell membrane or the compound itself was not able to inhibit viral infection within the host cells.

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analysis of FIPV-infected CRFK cells treated with the various concentrations of the hit compounds (a–b). Quantification of FIPV nucleic acids by RT-qPCR was presented as a percent of viral reduction (%) by the treatment conditions (upper panel). Intracytoplasmic staining pattern (lower panel) generated by IPMA reflected the FIPV antigens in the infected cells which was used for calculating EC50 as described in the text.

Pre- and post-viral absorption inhibitions were designed to determine antiviral potency of the selected compounds during viral entry to the host cells and after viral infection. The compound NSC629301 showed an effective EC50 values of 7.75 ± 0.48 μM and 6.20 ± 0.88 μM for pre- and post-viral absorption inhibitions, respectively (Table 1). The inhibitory effects of the compound NSC71097 were stronger than that of NSC629301 with the EC50 values of 4.03 ± 0.60 μM and 2.34 ± 0.96 μM, respectively. However, the compound NSC282187 did not show antiviral activity on both pre- and post-viral adsorption inhibitions at the highest concentration tested.

The SI value of the prophylaxis treatment of the compound NSC629301 was 2.17, which was higher than those of the pre- and post-viral adsorption inhibitions (1.71 and 2.14, respectively). In addition, the compound NSC71097 demonstrated the better SI values of 3.69 for prophylaxis treatment, 2.21 for the post-viral absorption inhibition and 7.40 for the pre-viral adsorption inhibition. In accordant to the EC50 values obtained from the IPMA results, RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated the significantly decreased copy numbers of FIPV RNAs with the higher concentration of each compound (Fig. 3). In this study, 1% DMSO was used instead of the compound in the mock-treated FIPV infected CRFK cells as a non-inhibitor control, which was not influent on the FIPV infectivity (data not shown). Moreover, we also tested antiviral activity of GC-376 on FIPV as it has been shown to be a potent anti-FIPV (Kim et al., 2016) and the results are demonstrated in Table 1. In addition, the antiviral effects of NSC629301, NSC71097 and GC-376 on TGEV—a porcine alphacoronavirus—were determined. The results showed that NSC629301 and the NSC71097 could inhibit TGEV replication more efficient than ribavirin and lopinavir, but not GC-376. The level of inhibition were comparable to those finding in FIPV (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

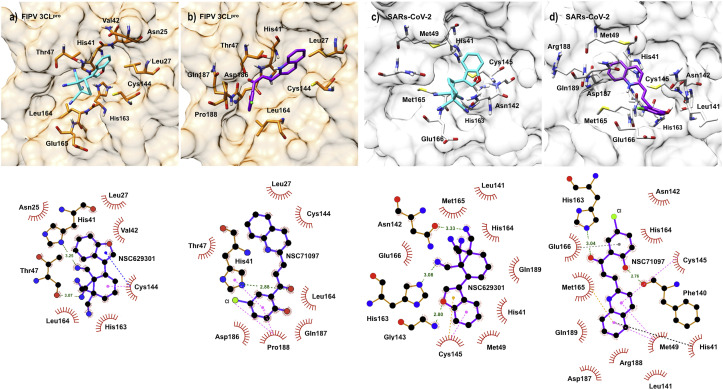

3.4. Interaction of FIPV 3CLpro and SARS-CoV-2 with compounds within catalytic dyads

We also studied the interaction of NSC629301 and NSC71097 with FIPV 3CLpro binding pocket using molecular docking simulation and protein ligand interaction analysis (Fig. 4 ). The results showed that the molecule of NSC629301 folded and fit well within the active site of the FIPV 3CLpro (Fig. 4a). Two nitrogen atoms of a benzonitrile group formed hydrogen bonds with His41 and Thr47 residues. The compound buried perfectly in the binding pocket and Cys144 residue can form non-covalent bonds, such as π-alkyl and π-donor interactions with benzofuran and nitrile functional groups, respectively. For NSC71097, the compound favorably located into the active site of FIPV 3CLpro (Fig. 4b). Particularly, His41 residue in the catalytic dyad links with an oxygen atom with a hydrogen bond, and also form a π-π stack bond to the 4-chlorophenol functional group of this compound. In addition, Pro188 can form an amide-π stack with 4-chlorophenol functional group and form an alkyl bond to the chloride atom of this functional group. His41 and Cys144, the active residues of FIPV 3CLpro, form the π-alkyl interaction and hydrogen bond to the compound, respectively.

Fig. 4.

The FIPV 3CLpro–compound and SARs-CoV-2 3CLpro– compound interactions in the binding pocket of NSC629301 (a and c; cyan) and NSC71097 (b and d; purple) are presented in the upper panel. The interactions are presented as dashed lines for alkyl/π-alkyl bonds (pink), π-donor (dark blue), hydrogen bonds (green), π-sulfur (yellow), π-anion (gray), π- π stack (black) and hydrophobic interaction (red circles and ellipses) in the lower panel. The visualizations are generated using UCSF Chimera version 1.10.2, LigPlot software version v.2.0 and Discovery Studio Visualizer 2017 v.12.0.

Interactions between the compounds and SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro were determined based on the PDB ID: 6LU7. pdb (Jin et al., 2020) by molecular docking analysis. NSC629301 forms hydrogen bonds with Asn142, Gly143, and His163 residues. Cys145 of catalytic dyad also reacts to benzofuran with π-alkyl and π-sulfur interactions (Fig. 4c). NSC71097 can form hydrogen bonds with Phe140 and His163. π-alkyl interaction was observed between NSC71097 and Met49 and Cys145. The π-alkyl, π-anion and π-π stack interactions were founded with Met165, Glu166, and His41, respectively (Fig. 4d). However, the binding affinities of the two candidate compounds (NSC629301 = −7.4 kcal/mol, and NSC71097 = −7.5 kcal/mol) were slightly weaker than those of FIPV 3CLpro.

The Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity (ADME/T) properties of the three compounds are shown in Supplementary Table 2. All three compounds –NSC282187, NSC629301, and NSC71097– did not violate the druglikeness of Lipinski's rule of five when analyzed using SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch). They were also predicted to be well absorped in gastrointestinal tract. Moreover, compounds NSC282187 and NSC71097 might be able to permeate blood-brain barrier (BBB) as shown in Supplementary Table 2. None of them shows cytotoxicity (e.g. mutagenic, tumorigenic, reproductive, and irritant effects).

Moreover, we further screened the compounds structurally related to our two candidates. Twelve structures were found for NSC71097 and 6 of 12 analogues from the PubChem databases passed the Lipinski's rule of five. The molecular docking analysis showed that CID: 3,689,607 and CID: 247,236 (NSC61622) hit the best rank with binding affinities of −7.2 and −7.6 kcal/mol, respectively, which were slightly weaker than that of NSC71097 prototype (−8.5 kcal/mol). Ninety of 993 similar and available conformers were retrieved; the eleven top-ranked conformers showed better binding than the similar analogues with the ranges of −7.6 to −7.9 kcal/mol. Regarding to drug safety, all the related compounds demonstrated good characteristics for GI absorption and BBB penetration. Moreover, twelve related compounds are not mutagenic, tumorigenic or irritated and have no effect on the reproductive system (Supplementary Table 3). Only four analogues were found for the compound NSC629301; however, they are not commercially available. Two available conformers were retrieved and analyzed. The results showed that the binding affinity of CID: 300,334 (NSC174694) and CID: 282,235 (NSC 135431) to FIPV 3CLpro binding pocket were −6.6 kcal/mol and −6.5 kcal/mol, respectively, which were weaker than that of NSC629301. All related compounds and their interactions are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

4. Discussion

Although, several in vitro and in vivo experiments have been focusing on antiviral agents targeting 3CLpro of FIPV (Pedersen et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2012, 2013, 2016), a commercial antiviral agent is not yet available. A combined antiviral therapy could slow or limit the progression of viral diseases in humans; however, a similar therapy has not been proved to be effective in cats (Pedersen et al., 2018; Pedersen, 2014). In this study, the virtual screening has been applied on searching for potential anti-FIPV agents from available non-natural compounds (the diversity and the mechanical datasets) in the chemical libraries of National Cancer Institute (NCI) depository databases. The molecular docking using AutoDock Vina was used to rank the binding affinities between the favorable compounds and the catalytic dyad residues (His41 and Cys144) in the binding pocket of FIPV 3CLpro. The best top-ranked compounds were then re-docked to filter for good hits.

Protease inhibition activities of the best candidate compounds were subsequently tested by the direct protease inhibiton assay. We observed that NSC282187 (Carbamic acid, (4-fluorophenyl)-, 1,2-dihydro-2-oxo-3-pyridinyl ester) demonstrated the best IC50 and Ki values. In addition, this compound is quite similar to antiretroviral drugs against Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which contains a carmabic acid component, such as fosamprenavir––prodrug of amprenavir––(Arvieux and Tribut, 2005) and raltegravir––integrase strand transfer inhibitor––(Rokas et al., 2012). Lopinavir, the other HIV protease inhibitor, also contains carbamic acid (Cvetkovic and Goa, 2003), which has been used in combination with other antiretroviral drug, such as ritonavir for increasing bioavailability of lopinavir (Crommentuyn et al., 2005; Cvetkovic and Goa, 2003; van Heeswijk et al., 2001). The combined lopinavir/ritonavir regime was recently applied for MERS-CoV infected patients, but the controversial efficiencies were found in COVID-19 therapy resulting in recent discontinuing these drugs (Cao et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020; Sheahan et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). In our study, the compound NSC282187 demonstrated inhibitory effect on CoVs-3CLpro greater than lopinavir (IC50 = 224.81 ± 43.90 μM). Unfortunately, NSC282187 did not show an active antiviral effect in both FIPV and TGEV cell-based assay. According to ADME/T properties, NSC282187 has a good solubility property. This compound might be well dissolved in the cell culture media, but might not reach to the active potency level in the microenvironment of the cell-based assay in our study. We propose that the ligand should be further modified to contain a functional group to enhance lipophilicity as well as maintain adequate bioavailability.

Both NSC629301 and NSC71097 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) depository database are non-natural compounds. The chemical nomenclatures of the compounds are 3,6-dihydro-3,6-ethanocyclohepta (cd) (1) benzofuran-10,10,11,11-tetracarbonitrile (for NSC629301) and 1-(5-chloro-2-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(2-quinolinyl)-2-propen-1-one (for NSC71097). The information of these compounds on pathogenic organisms was limited. The compound NSC629301 selectively targeted to the damage checkpoint and repair (DDCR) genes in yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Tamble et al., 2011). Recently, NSC71097 has been shown to have the effects on either inhibition or increase enzymatic activity of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) from a pathogenic plant fungus, oomycete, suggesting that NSC71097 acted as electron acceptors for DHODH of Phytophthora infestans (Garavito et al., 2019). Thus far, there is neither a report on their antiviral screening nor antimicrobial activities. Our study is the first report on antiviral properties of NSC629301 and NSC71097.

Ribavirin has been well known as a broad spectrum antiviral agents, particularly for RNA viruses (Cameron and Castro, 2001). Inhibitory dose of ribavirin for FIPV in CRFK cells was 50–100 μg/ml which CPE was still observed in the FIPV-infected cells (Weiss and Oostrom-Ram, 1989). The other study showed that ribavirin might have direct or indirect effects on the FCoV replication (Barlough and Shacklett, 1994). We have shown that the compounds NSC629301 and NSC71097 could inhibit viral growth at higher efficacy than the board spectrum antiviral drug (ribavirin) and the HIV protease inhibitor (lopinavir). However, most effective antiviral drugs specifically inhibit viral replication at the early stage of infection which mainly target the key regulatory proteins of viral replication cycle such as viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, proteases and integrase.

In the recent reports, nucleoside analogues and peptidyl compounds exhibited an inhibitory effect on FIPV. Remdesivir and its derivative (GS-5734 and GS-441524) are nucleoside analogues that could impede FIPV replication both in vitro and in vivo (Murphy et al., 2018). The dipeptidyl aldehyde (GC-373) has been shown to be highly effective both in vitro 3CLpro assay and in experimentally infected cats (Kim et al., 2016) as well as in the cell-based assay in our study. However, this inhibitor could not completely clear FIPV in naturally FIP affected cats, in particular those with neurological signs (Pedersen et al., 2018). Additionally, recurrent FIP clinical signs were observed in some infected cats. Thus, we investigated how the compound GC-376 reacts to our 3CLpro structure. The homology modeling and molecular docking showed that the binding affinity of GC-376 was −7.5 kcal/mol, indicating lower interaction between GC-376 and the catalytic dyad compared to our three compounds (NSC282187 = −8.2 kcal/mol, NSC629301 = −8.4 kcal/mol, and NSC71097 = −8.5 kcal/mol, respectively). Regarding the physicochemical properties, GC-376 possessed less lipophilic property with log Po/w value = −12.77, suggesting poor BBB penetration and GI absorption.

The three compounds in this study may be the promising lead molecules for antiviral agent development to be used as alternative or combinatorial drugs to combat FIPV. As the binding pockets of CoVs-3CLpro are highly conserved, further application of these compounds for other CoVs is possible. The SARS-CoV-2 causes COVID-19 is markedly devastating to human health and economics worldwide. This novel coronavirus is among three zoonotic coronaviruses including SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV that posts the global public health awareness (Munster et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020). However, handling these zoonotic CoVs requires limited numbers of BSL3 laboratories. We propose the use of FIPV as a viral surrogate platform for screening anti-CoV agents and studying 3CLpro activity to expand spectrum of drug like molecules for further downstream development process.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (grant number RTA6280011); Agricultural Research Development Agency (grant number CRP6305032230) and The New Southbound Policy and the Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104927.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary Fig. 1.

The phylogenic tree demonstrates the amino acid sequence relations among 3CLpro of CoVs based on amino acid comparison. The 3CLpro of FIPV was closely related to that of TGEV and PEDV and also shared superclustering with the betacoronaviruses (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV) (a). The analysis of CoVs-3CLpro alignment by T-coffee and visualized by Jalview (v2.11.0) revealed the conserved amino acid residues (blue highlight). The two conserved amino acid residues, His41 and Cys144/145/148, which play an important role on the 3CLpro function, are indicated in the alignments (b, red arrows). The 3CLpro structures with focusing on the substrate binding pocket of CoVs are superimposed to demonstrate the conserved 3D structures of the catalytic dyads (c). Analysis of complexes between CoVs-3CLpro with the two best compounds revealed that both compounds are completely buried within the binding pockets. The NSC629301 and NSC71097 are presented in cyan and dark purple, respectively. For clarity, the complexes between a single CoV-3CLpro and each small molecule are shown in (d).

Supplementary Fig. 2.

Antiviral activities of two candidate compounds against TGEV replication in SK6 cells with the various concentrations of compounds at 0.01, 0.1, 1, 5, 10, 50, and 100 μM, respectively. The IPMA detects TGEV antigens in the cytoplasm of the SK6-infected cells.

References

- Arvieux C., Tribut O. Amprenavir or fosamprenavir plus ritonavir in HIV infection. Drugs. 2005;65:633–659. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babicki S., Arndt D., Marcu A., Liang Y., Grant J.R., Maciejewski A., Wishart D.S. Heatmapper: web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W147–W153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlough J.E., Shacklett B.L. Antiviral studies of feline infectious peritonitis virus in vitro. Vet. Rec. 1994;135:177–179. doi: 10.1136/vr.135.8.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigel J.H., Tomashek K.M., Dodd L.E., Mehta A.K., Zingman B.S., Kalil A.C., Hohmann E., Chu H.Y., Luetkemeyer A., Kline S., Lopez de Castilla D., Finberg R.W., Dierberg K., Tapson V., Hsieh L., Patterson T.F., Paredes R., Sweeney D.A., Short W.R., Touloumi G., Lye D.C., Ohmagari N., Oh M., Ruiz-Palacios G.M., Benfield T., Fätkenheuer G., Kortepeter M.G., Atmar R.L., Creech C.B., Lundgren J., Babiker A.G., Pett S., Neaton J.D., Burgess T.H., Bonnett T., Green M., Makowski M., Osinusi A., Nayak S., Lane H.C. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19 — preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron C.E., Castro C. The mechanism of action of ribavirin: lethal mutagenesis of RNA virus genomes mediated by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2001;14:757–764. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200112000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang Jingli, Fan G., Ruan L., Song B., Cai Y., Wei M., Li X., Xia J., Chen N., Xiang J., Yu T., Bai T., Xie X., Zhang L., Li C., Yuan Y., Chen H., Li Huadong, Huang H., Tu S., Gong F., Liu Y., Wei Y., Dong C., Zhou F., Gu X., Xu J., Liu Z., Zhang Y., Li Hui, Shang L., Wang K., Li K., Zhou X., Dong X., Qu Z., Lu S., Hu X., Ruan S., Luo S., Wu J., Peng L., Cheng F., Pan L., Zou J., Jia C., Wang Juan, Liu X., Wang S., Wu X., Ge Q., He J., Zhan H., Qiu F., Guo L., Huang C., Jaki T., Hayden F.G., Horby P.W., Zhang D., Wang C. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Interim Laboratory Biosafety Guidelines for Handling and Processing Specimens Associated with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/lab/lab-biosafety-guidelines.html [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . fifth ed. 2009. Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL)https://www.cdc.gov/labs/BMBL.html/ [Google Scholar]

- Crommentuyn K.M.L., Kappelhoff B.S., Mulder J.W., Mairuhu A.T.A., Van Gorp E.C.M., Meenhorst P.L., Huitema A.D.R., Beijnen J.H. Population pharmacokinetics of lopinavir in combination with ritonavir in HIV-1-infected patients. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005;60:378–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvetkovic R.S., Goa K.L. Lopinavir/Ritonavir: a review of its use in the management of HIV infection. Drugs. 2003;63:769–802. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavito M.F., Narvaez-ortiz H.Y., Pulido D.C., Löffler M., Judelson H.S., Restrepo S., Zimmermann B.H. Phytophthora infestans Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase is a potential target for chemical control – a comparison with the enzyme from solanum tuberosum. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasiti Kankanamalage A.C., Kim Y., Damalanka V.C., Rathnayake A.D., Fehr A.R., Mehzabeen N., Battaile K.P., Lovell S., Lushington G.H., Perlman S., Chang K.O., Groutas W.C. Structure-guided design of potent and permeable inhibitors of MERS coronavirus 3CL protease that utilize a piperidine moiety as a novel design element. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;150:334–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grein J., Ohmagari N., Shin D., Diaz G., Asperges E., Castagna A., Feldt T., Green G., Green M.L., Lescure F.X., Nicastri E., Oda R., Yo K., Quiros-Roldan E., Studemeister A., Redinski J., Ahmed S., Bernett J., Chelliah D., Chen D., Chihara S., Cohen S.H., Cunningham J., D'Arminio Monforte A., Ismail S., Kato H., Lapadula G., L'Her E., Maeno T., Majumder S., Massari M., Mora-Rillo M., Mutoh Y., Nguyen D., Verweij E., Zoufaly A., Osinusi A.O., DeZure A., Zhao Y., Zhong L., Chokkalingam A., Elboudwarej E., Telep L., Timbs L., Henne I., Sellers S., Cao H., Tan S.K., Winterbourne L., Desai P., Mera R., Gaggar A., Myers R.P., Brainard D.M., Childs R., Flanigan T. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2327–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrewegh A.A., de Groot R.J., Cepica A., Egberink H.F., Horzinek M.C., Rottier P.J. Detection of feline coronavirus RNA in feces, tissues, and body fluids of naturally infected cats by reverse transcriptase PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995;33:684–689. doi: 10.1128/JCM.33.3.684-689.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan , China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu M.-F., Kuo C.-J., Chang K.-T., Chang H.-C., Chou C.-C., Ko T.-P., Shr H.-L., Chang G.-G., Wang A.H.-J., Liang P.-H. Mechanism of the maturation process of SARS-CoV 3CL protease. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:31257–31266. doi: 10.1074/JBC.M502577200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Duan Y., Yu J., Wang L., Yang K., Liu F., Jiang R., Yang Xinglou, You T., Liu Xiaoce, Yang Xiuna, Bai F., Liu H., Liu Xiang, Guddat L.W., Xu W., Xiao G., Qin C., Shi Z., Jiang H., Rao Z., Yang H. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Liu H., Kankanamalage A.C.G. Reversal of the progression of fatal coronavirus infection in cats by a broad- spectrum coronavirus protease inhibitor. 2016. 1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim Y., Rao S., Groutas W.C., Chang K.O., Mandadapu S.R., Groutas W.C., Chang K.O. Potent inhibition of feline coronaviruses with peptidyl compounds targeting coronavirus 3C-like protease. Antivir. Res. 2013;97:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Lovell S., Tiew K.-C., Mandadapu S.R., Alliston K.R., Battaile K.P., Groutas W.C., Chang K.-O. Broad-spectrum antivirals against 3C or 3C-like proteases of picornaviruses, noroviruses, and coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2012;86:11754–11762. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01348-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C.J., Chi Y.H., Hsu J.T.A., Liang P.H. Characterization of SARS main protease and inhibitor assay using a fluorogenic substrate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;318:862–867. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., Swindells M.B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekcharoensuk P., Wiriyarat W., Petcharat N., Lekcharoensuk C., Auewarakul P., Richt J.A. Cloned cDNA of A/swine/Iowa/15/1930 internal genes as a candidate backbone for reverse genetics vaccine against influenza A viruses. Vaccine. 2012;30:1453–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.109. Feb Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004;1:337–341. doi: 10.1016/J.DDTEC.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manasateinkij W., Nilkumhang P., Jaroensong T., Noosud J., Lekcharoensuk C., Lekcharoensuk P. Occurrence of feline coronavirus and feline infectious peritonitis virus in Thailand. Kasetsart J./Nat. Sci. 2009;43:720–726. [Google Scholar]

- Munster V.J., Koopmans M., van Doremalen N., van Riel D., de Wit E. A novel coronavirus emerging in China — key questions for impact assessment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:692–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2000929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy B.G., Perron M., Murakami E., Bauer K., Park Y., Eckstrand C., Liepnieks M., Pedersen N.C. The nucleoside analog GS-441524 strongly inhibits feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) virus in tissue culture and experimental cat infection studies. Vet. Microbiol. 2018;219:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Boyle N.M., Banck M., James C.A., Morley C., Vandermeersch T., Hutchison G.R. Open Babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminf. 2011;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C., Liepnieks M., Perron M., Murakami E., Murphy B.G., Eckstrand C., Park Y., Bauer K. The nucleoside analog GS-441524 strongly inhibits feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) virus in tissue culture and experimental cat infection studies. Vet. Microbiol. 2018;219:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C. An update on feline infectious peritonitis: diagnostics and therapeutics. Vet. J. 2014;201:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokas K.E.E., Bookstaver P.B., Shamroe C.L., Sutton S.S., Millisor V.E., Bryant J.E., Weissman S.B. Role of raltegravir in HIV-1 management. Ann. Pharmacother. 2012;46:578–589. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan T.P., Sims A.C., Leist S.R., Schäfer A., Won J., Brown A.J., Montgomery S.A., Hogg A., Babusis D., Clarke M.O., Spahn J.E., Bauer L., Sellers S., Porter D., Feng J.Y., Cihlar T., Jordan R., Denison M.R., Baric R.S. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:222. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13940-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes J.E., Papich M.G. Elsevier Inc; 2013. Antiviral and Immunomodulatory Drugs, Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamble C.M., St R.P., Giaever G., Nislow C., Williams A.G., Stuart M., Lokey R.S. The synthetic genetic interaction network reveals small molecules that target specific pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae w. Mol. Biosyst. 2011;7:2019–2030. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00298d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theerawatanasirikul S., Kuo C.J., Phetcharat N., Lekcharoensuk P. In silico and in vitro analysis of small molecules and natural compounds targeting the 3CL protease of feline infectious peritonitis virus. Antivir. Res. 2020;174:104697. doi: 10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2019.104697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heeswijk R.P., Veldkamp A., Mulder J.W., Meenhorst P.L., Lange J.M., Beijnen J.H., Hoetelmans R.M. Combination of protease inhibitors for the treatment of HIV-1-infected patients: a review of pharmacokinetics and clinical experience. Antivir. Ther. 2001;6:201–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Chen C., Liu X., Yang K., Xu X., Yang H. Crystal structure of feline infectious peritonitis virus main protease in complex with synergetic dual inhibitors. J. Virol. 2016;90:1910–1917. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02685-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Chen C., Yang K., Xu Y., Liu Xiaomei, Gao F., Liu H., Chen X., Zhao Q., Liu Xiang, Cai Y., Yang H. Michael acceptor-based peptidomimetic inhibitor of main protease from porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:3212–3216. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R.C., Oostrom-Ram T. Inhibitory effects of ribavirin alone or combined with human alpha interferon on feline infectious peritonitis virus replication in vitro. Vet. Microbiol. 1989;20:255–265. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(89)90049-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes R.P., Hartmann K. Update on antiviral therapies. August’s Consult. Feline Intern. Med. 2016;7:84–96. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-22652-3.00007-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. WHO Discontinues Hydroxychloroquine and Lopinavir/ritonavir Treatment Arms for COVID-19.https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/04-07-2020-who-discontinues-hydroxychloroquine-and-lopinavir-ritonavir-treatment-arms-for-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Xie W., Xue X., Yang K., Ma J., Liang W., Zhao Q., Zhou Z., Pei D., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R., Yuen K.Y., Wong L., Gao G., Chen S., Chen Z., Ma D., Bartlam M., Rao Z. Design of wide-spectrum inhibitors targeting coronavirus main proteases. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.