Abstract

Interferons are secreted cytokines with potent antiviral, antitumor and immunomodulatory functions. As the first line of defense against viruses, this pathway restricts virus infection and spread. On the contrary, viruses have evolved ingenious strategies to evade host immune responses including the interferon pathway. Multiple families of viruses, in particular, DNA viruses, encode microRNA (miR) that are small, non-protein coding, regulatory RNAs. Virus-derived miRNAs (v-miR) function by targeting host and virus-encoded transcripts and are critical in shaping host-pathogen interaction. The role of v-miRs in viral pathogenesis is emerging as demonstrated by their function in subverting host defense mechanisms and regulating fundamental biological processes such as cell survival, proliferation, modulation of viral life-cycle phase. In this review, we will discuss the role of v-miRs in the suppression of host genes involved in the viral nucleic acid detection, JAK-STAT pathway, and cytokine-mediated antiviral gene activation to favor viral replication and persistence. This information has yielded new insights into our understanding of how v-miRs promote viral evasion of host immunity and likely provide novel antiviral therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Viruses, viral microRNA, interferons, post-transcriptional silencing, immune response

1. INTRODUCTION

Viruses are ubiquitous, non-cellular pathogens that infect unicellular to multicellular organisms. Different viral hosts have evolved unique mechanisms to restrict virus infection and spread. For instance, bacteria have developed Clustered Regulatory Inter-spaced Short Palindromic Repeat (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) nuclease based pathways to degrade invading viruses, small interfering (si) RNA pathways potently restrict viral infection in plants, while interferon (IFN) production and signaling acts as antiviral mechanism in vertebrates [1–5]. IFN signaling pathway is an innate immune response against invading viruses and acts as the first line of defense [6]. Viruses have co-evolved with their hosts to counter their antiviral mechanisms. One such recently discovered pathway in viruses is the discovery of virus-encoded microRNAs (v-miR).

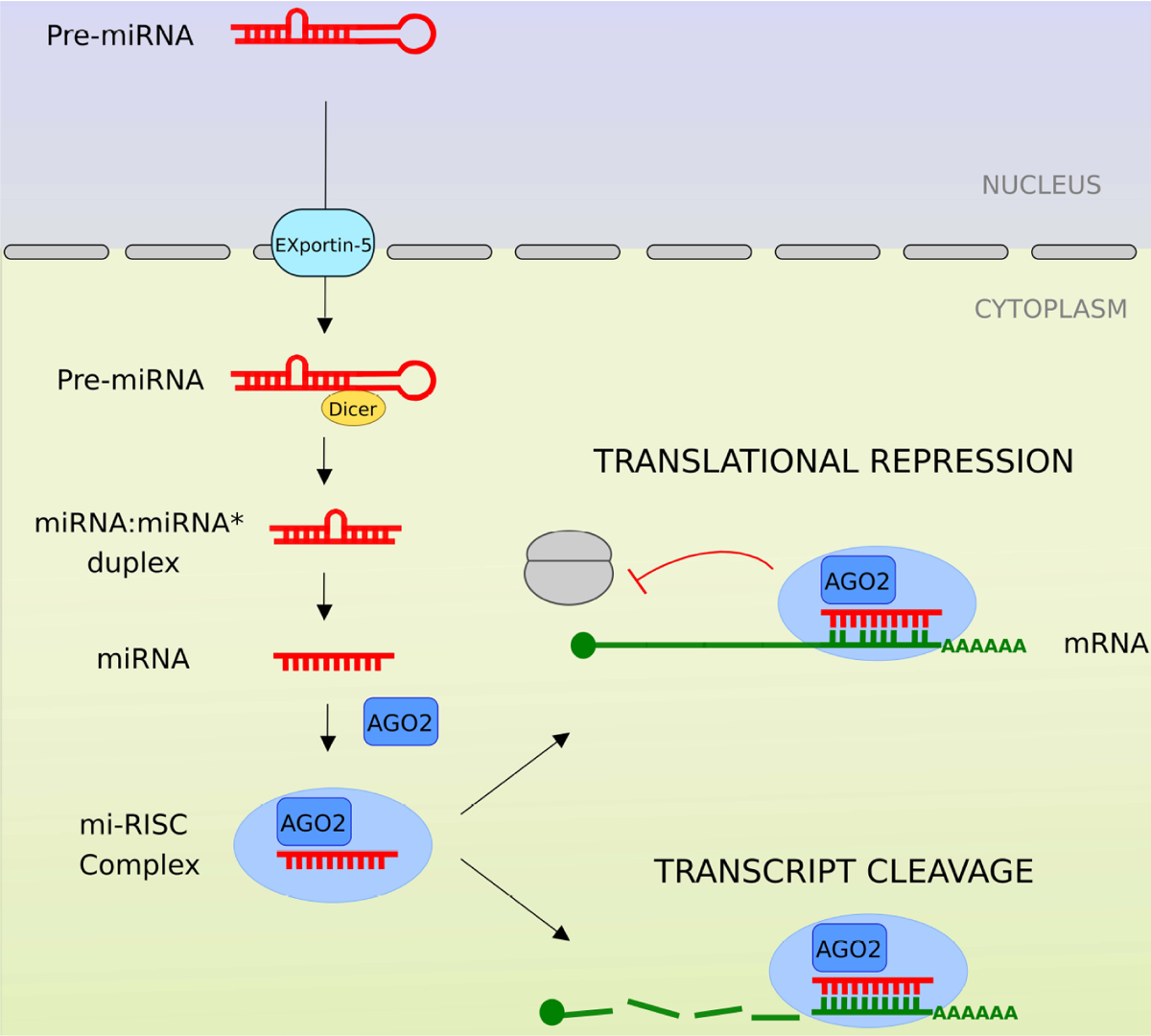

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small (21–25 nts), noncoding RNA molecules that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by base-pairing with its mRNA target [7, 8] (Fig. 1). As a viral mechanism of immune evasion, v-miRs regulate virus and host transcript expression. So far, more than 250 v-miRs have been discovered in different virus families (http://www.mirbase.org; version 22.1), predominantly those with DNA genomes including herpesviruses and polyomaviruses [9, 10]. Biogenesis of v-miRs is completely dependent on host miRNA machinery, indicating that viruses have incorporated multifunctional noncoding RNAs during evolution. Due to their small size, lack of immunogenicity, and the ability to post-transcriptionally regulate gene (host and viral) expression, v-miRs facilitate virus survival and spread [7, 11]. Not surprisingly, increased accumulation of v-miRs has been associated with the pathogenesis of various diseases including cancers, oral inflamma-tion, etc., [12–14].

Fig. (1). Mechanism of action of microRNA.

Viral miRNA biogenesis, similar to cellular miRNA, is dependent on the host miRNA machinery. Precursor vmiRs are generated in the nucleus and are exported to the cytoplasm. Pre-v-miRs are processed by Dicer and subsequently incorporated by Argonaute (AGO2)-associated miRNA-induced silencing complex (mi-RISC). Mature, single stranded, v-miR binds to cognate mRNA harboring complementary sequences. Viral miRNA guides host RNA endonuclease Argonaute (AGO2)-associated mi-RISC to either enhance degradation or suppress translation of target (host or viral) transcripts.

V-miRs target both the host and viral genes to interfere with the activation of interferon signaling that elicit antiviral pathways and inhibit viral replication, clear virus-infected cells or trigger viral latency. In this review, we will focus on v-miR-mediated suppression of the host interferon pathway.

2. INTERFERON SIGNALING PATHWAY

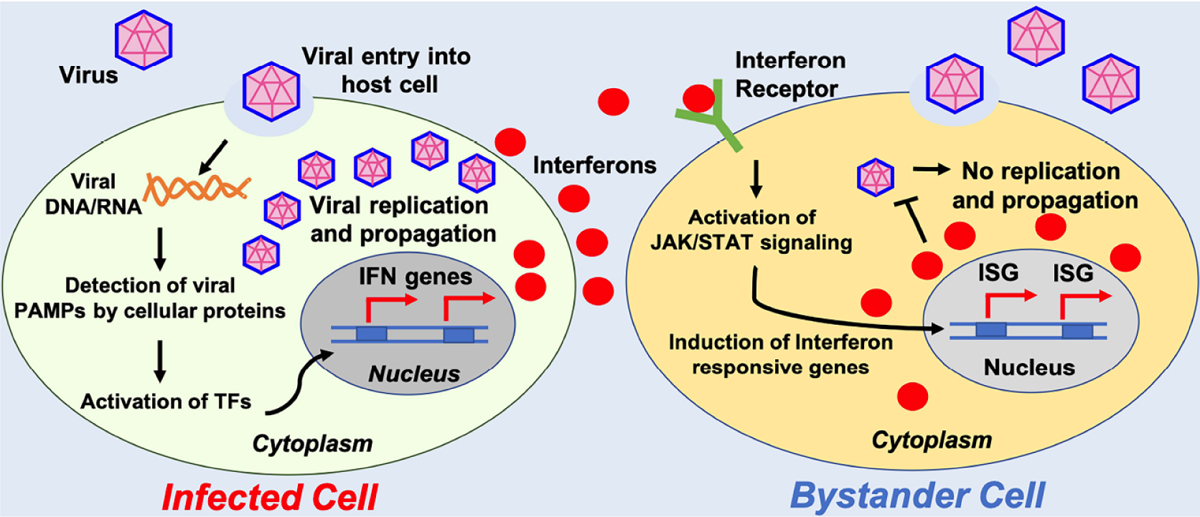

Cells infected by virus triggers an inflammatory process, which secretes interferons, among other molecules, such as, prostaglandins and interleukins [15]. Interferons were firstly described in 1957 by Alick Isaacs and Jean Lindenmann [16, 17] as proteins secreted by virus-infected cells that are capable of protecting other cells from a viral infection, because interferons stimulate the production of antiviral proteins in non-infected cells that inhibit the replication of dif-ferent types of viruses (Fig. 2).

Fig. (2). Activation of interferon pathway can potently restrict and clear virus.

Interferon pathway is an innate immune response activated by virusinfected cells. Recognition of virus-derived factors or replication intermediates (nucleic acids) can actívate host signaling cascade that can induce production of interferons. These secreted molecules act in paracrine (and autocrine) manner to actívate neighboring cells to induce antiviral state.

2.1. Types of Interferons

Interferons (IFNs) are cytokines that play a central role in initiating immune responses, especially antiviral and antitumor effects. There are three types of IFNs: type I (includes IFN-alpha, -beta and others, such as omega, epsilon, and kappa), type II (IFN-gamma) and type III (IFN-lambda) [18]. In this review, we mainly focussed on type I IFNs alpha and beta and type II IFN-gamma.

Type 1 is represented by interferon-alpha (IFNα) and interferon beta (IFNβ). Both have a very similar biological activity and molecular structures and mainly take part in the innate immune response. IFNα is mainly produced by virus-infected leukocytes, while IFNβ is produced by virus-infected fibroblasts. IFNα also stimulates the synthesis of class I proteins of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC-I). These molecules are present in the membranes of all nucleus-containing cells and participate in the presentation of antigens (in particular viral antigens) to be recognized by the immune system [19].

Type 2 interferon is represented by IFNγ, also called immune interferon. This IFN acts as a lymphokine because it acti-vates other cells of the immune system, such as natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and B lymphocytes. It is particularly effective in controlling infections caused by viruses capable of inhibiting the synthesis of RNA and cellular proteins before the synthesis of interferon type I commences [20].

2.2. Interferon Signaling Pathway

Both type I and II IFNs exert their actions through cognate receptor complexes IFNAR and IFNGR respectively, present on the cell surface [18]. Type I IFNs are recognized by broadly expressed heterodimeric receptors composed of the IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 subunits, while the type II IFN receptor consists of IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 [21,22]. Type III interferon lambda has three members: lambda 1 (IL-29), lambda 2 (IL-28A), and lambda 3 (IL-28B) respectively. IFN-lambda signaling is initiated through a unique heterodimeric recep-tor composed of IFN-LR1/IF-28Rα and IL10R2 chains [23].

All Interferons bind to their receptor on the cell surface and initiate a signaling cascade through the proteins of Janus Kinases (JAK) and Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (STAT) family members, that drive the transcription of Interferon Stimulated Genes (ISGs) [24].

JAK family proteins [JAK1, JAK2 and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2)] are bound to the cytoplasmic domain of IFN receptors in an inactive state but upon IFN binding to the receptor, undergo activation through cross-phosphorylation [25, 26]. Activated JAK phosphorylates the IFN receptors on tyrosine residues, which leads to the binding and phosphorylation of STATs [15, 16]. The phosphorylated STAT is then released from the receptor, form homo or het-erodimer and translocate to the nucleus and activate the transcrip-tion of ISGs [27, 28]. STAT family has seven members (STAT1-STAT4, STAT5a, STAT5b and STAT6) but STAT1 and STAT2 are the most critical components of IFN signaling [29].

Type I IFNs typically recruit JAK1 and TYK2 proteins to transduce their signals through STAT1 and STAT2 heterodimers; in combination with IRF9 (IFN-regulatory factor 9), these proteins form the ISG factor 3 (ISGF3) complex. In the nucleus, ISGF3 binds to IFN-stimulated response elements (ISRE) to promote gene induction [30–32]. Type II IFNs, in turn rely upon the activation of JAK1 and 2 and STAT1. Once activated, STAT1 dimerizes to form the transcriptional regulator GAF (IFNG activated factor) and this binds to the IFNG activated sequence (GAS) elements and initiates the transcription of IFNG-responsive genes [33, 34].

3. VIRUS -MEDIATED ANTIVIRAL MECHANISMS

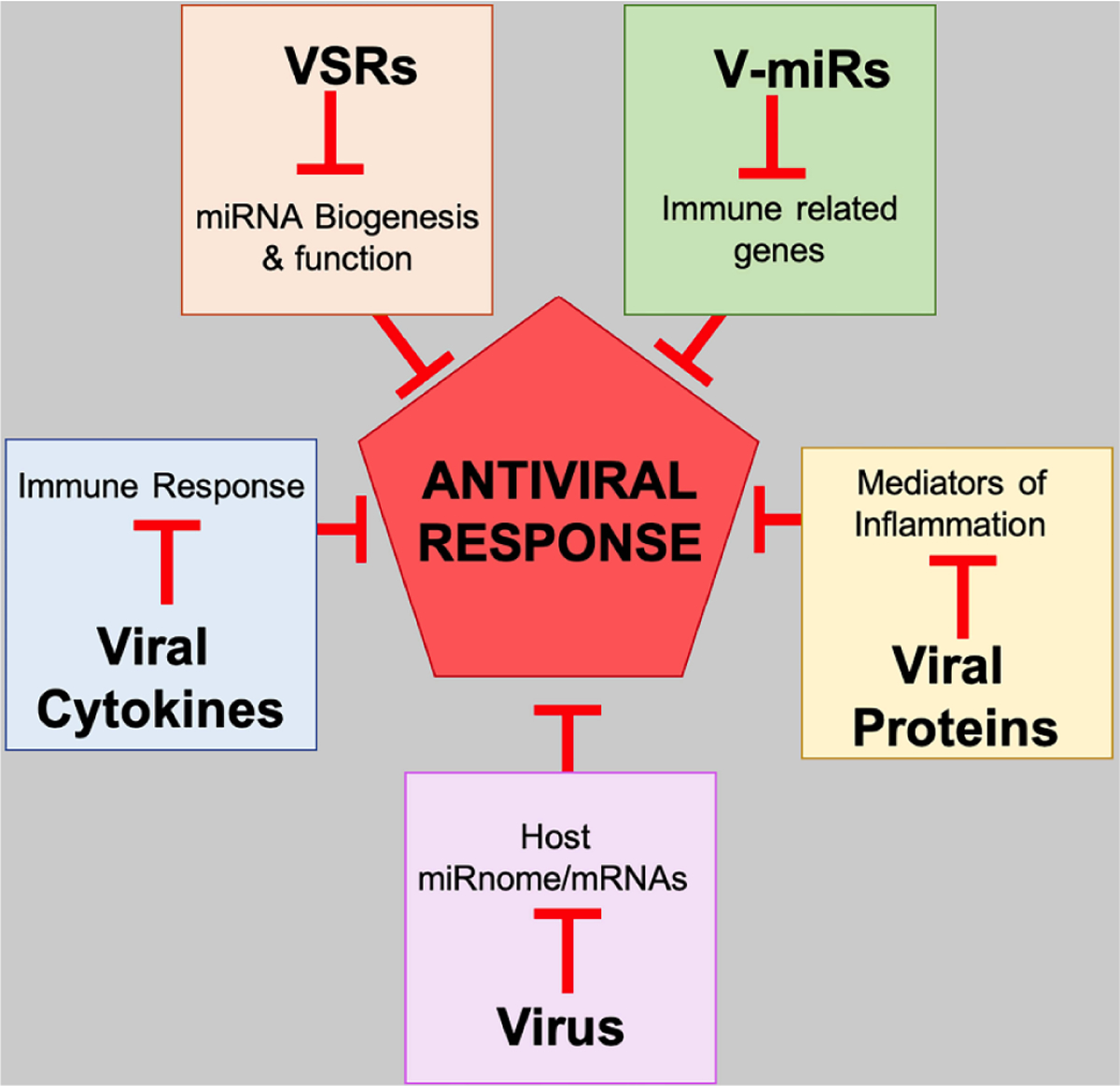

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are molecules associated with groups of pathogens that are recognized by cells of the innate immune system. These molecules can be referred to as small molecular motifs conserved within a class of microbes. For instance, the dsRNA molecules, genome structure or replicative intermediates can act as PAMPs in case of viruses. Host TLR (Toll-Like Receptors) and other pattern recognition receptors (PRRs; also called pathogen recognition receptors) can detect PAMPs. However, viruses have evolved multiple mechanisms to evade innate and adaptive immune responses to successfully invade and persist inside the host. These pathways can be broadly classified into five different categories (Fig. 3).

Fig. (3). Strategies employed by virus to modulate host antiviral response.

Viruses have evolved multiple strategies to evade or block antiviral response generated by host. Virus infection leads to global changes in host transcriptome (miRnome and mRNAs). Many viruses secrete cytokine homologs, which modulate immune response. Viral suppressors of RNAi (VSRs) are viral proteins which interfere with host miRNA biogenesis. Virally encoded miRNAs (V-miRs) target and downregulate many immune related host genes. Viral proteins suppress inflammation by targeting inflammatory cytokines.

3.1. Virus-mediated Impact on Host miRnome/mRNAs

In animals, the microRNA pathway is considered effective against the virus. Host miRNAs have been shown to directly bind and interfere with the translation of viral transcripts. Multiple cellular miRNAs have been demonstrated to restrict HIV infection. Huang et al. showed that a cluster of five miRNA viz., miR-28, miR-125b, miR-150, miR-223 and miR-382 can bind to the 3’ region of HIV-1 mRNAs and suppress HIV-1 production in resting primary CD4+ T cells [35]. Similarly, miR-29b is shown to bind HIV-1 nef transcript causing reduced viral replication [36]. On the contrary, certain viruses require host miRNA for their tropism. Liver-specific miR-122 is required by Hepatitis C Virus (HCV). miR-122, a host miRNA, binds to the 5′ noncoding region of the viral genome and promotes viral replication [37]. Viruses are therefore both the target of host miRNAs and have evolved beneficial interactions with cellular miRNA.s

3.2. Viral Suppressors of RNA Induced Silencing (VSRs)

Upon sensing virus-derived RNA or RNA intermediates, host small RNA pathways (both miRNA and siRNA) are activated. To counter this, virus-derived factors (proteins or RNA) can suppress the host RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. Numerous animal and plant viral proteins have been shown to target different components of RNAi machinery. These studies determined that different suppressors interfere with unique components of the host-silencing machinery, suggesting that many viruses independently developed the means to suppress silencing. By blocking host RNAi, Viral Suppressor of RNAi (VSR) can confer pathogenicity to viruses. For influence miRNA biogenesis of the host to impair cell proliferation, immune response, and facilitate viral replication [38]. Recent studies showed HIV encoded Nef interacts with host GW182 protein (encoded by TNRC6A gene, an important component of RNAi pathway) via its GW (Glycine-Tryptophan) motifs and dysregulate its localization and sorting into exosomes [39]. Moreover, HIV-Nef overexpressing monocytes exhibit widespread changes in cellular and exosomal miRNAs [40]. B2 protein of Nodamura virus (NoV), an insect and mammal infecting virus, interferes with the activity of integral small RNA biogenesis factor Dicer [41]. NoV B2 directly binds to double-stranded RNA substrates of Dicer and likely post-Dicer activity products.

3.3. Viruses Encode Antiviral Cytokines

Virus-mediated modulation of the host immune response is critical in understanding virus-host interaction. Cytokine and cytokine-receptors are critical in mounting an effective antiviral response. Numerous viruses encode genes that are homologs of host cytokines, thereby dysregulating host immune responses. For instance, Kaposi Sarcoma-associated Virus (KHSV) is known to encode multiple cytokine homologs including ORF K2 (human IL-6), ORF 74 (IL-8-like receptor) [42, 43]. Similarly, IL-10 homologs have been identified in Herpesviruses and poxviruses. Viral IL-10 (vIL-10) exhibits immunosuppressive properties similar to host IL-10 suggesting that viruses have acquired cytokine functions to dysregulate host immunity [43, 44].

3.4. Viral Proteins Impair Host Responses

Virus-encoded proteins can also directly block interferon signaling. Considering the significance of the interferon pathway in locally restricting viruses, it is not surprising that viral protein-mediated suppression of host interferon signaling is a general mechanism. A vast literature on how viral proteins target interferon pathway exists and the list continues to grow. Viral proteins target essentially every stage of interferon signaling from ligand-receptor interaction to the activation of interferon-inducible genes. STATs are targeted by various viral proteins. NS5 protein of many Flaviviruses is known to antagonize IFNs through the modulation of STAT1 or STAT2. For example, NS5 of Dengue virus inhibits the phosphorylation of STAT2 and promotes its degradation. Simi-larly, Zika Virus NS5 also binds to STAT2 and triggers its degrada-tion. NS5 of the Japanese Encephalitis Virus, Langat virus and Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus suppress the phosphorylation of STAT1 [45]. Other viral proteins like Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) E6 protein target IRF3, a major inducer of type I interferons [46], while 3C protein of polio virus bind to and degrade RelA subunit of NFκB thereby abrogating proinflammatory cytokine production [47].

3.5. Viral miRNA-Mediated Impairment of Host Pathways

Viruses, in particular Herpesviruses, have been shown to encode miRNAs [9, 10]. Viral miRNAs, similar to host miRs, can simultaneously target multiple host and viral transcripts and therefore can modulate host and viral transcriptome [48–50]. Evidently, these noncoding RNA acts as crucial molecular switches that regulate virus-host interaction. More importantly, these tiny RNA molecules can hijack host exosomal pathway to reach distant sites, are non-immunogenic and can play major role in viral spread and persistence [49, 51]. V-miRs can function in autocrine and paracrine fashion to counter antiviral pathway in infected cells and likely modulate immune responses in bystander cells (Fig. 2).

4. VIRAL MICRORNA SUPPRESSION OF INTERFERON SIGNALING

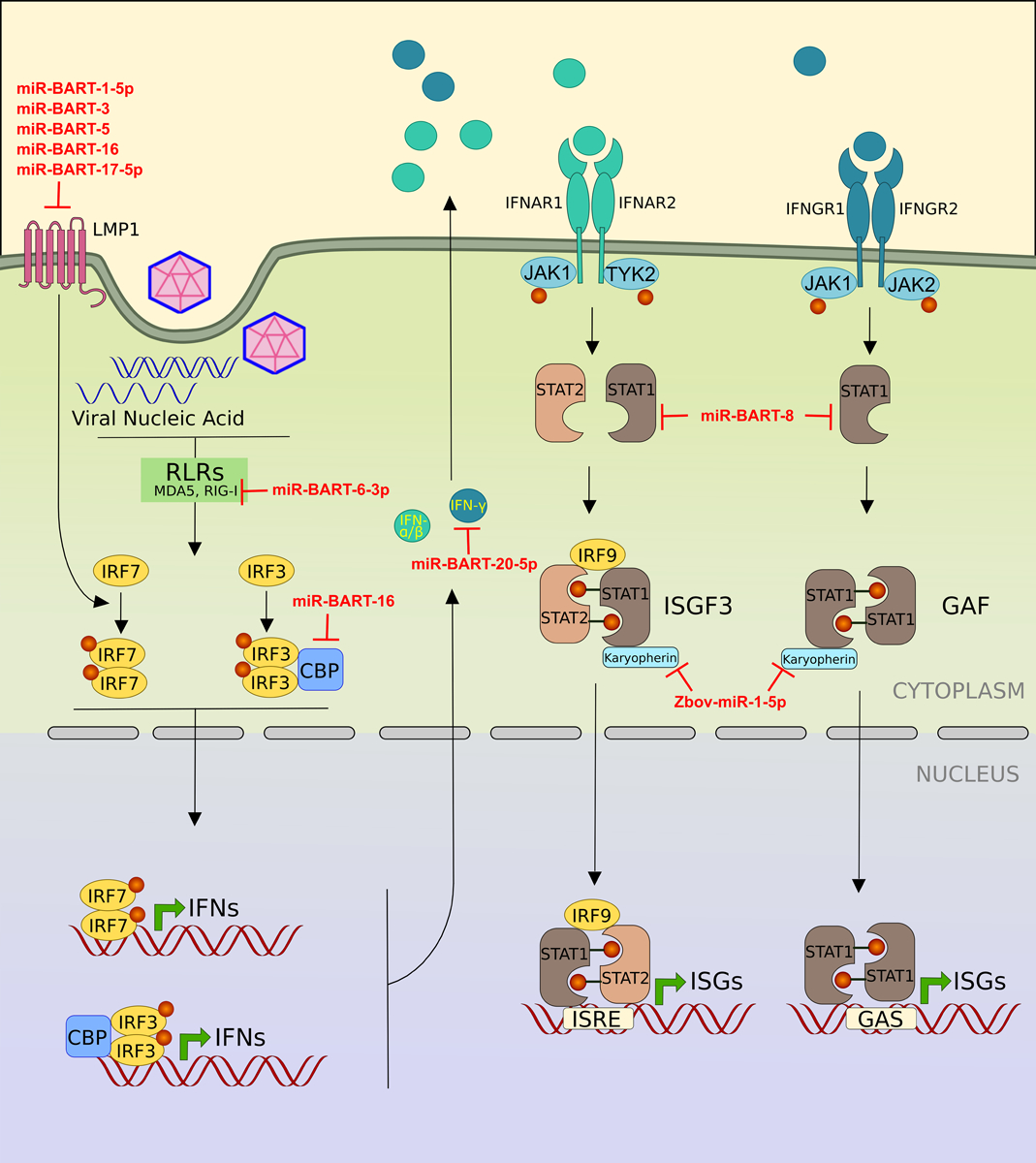

Viral miRNAs have been shown to modulate the host interferon pathway, directly or indirectly, through the inhibition of specific host transcripts that act as critical regulators of the interferon response and the immune response as a whole. DNA tumor viruses are of particular interest because they establish long-term infection and therefore must efficiently and consistently evade the immune response. These viruses encode miRNAs that may protect viral transcripts from the innate antiviral host interferon response in particular [52]. Fig. 4 shows viral miRNAs from different viruses and their targets in interferon signaling pathway (also listed in Table 1).

Fig. (4). Viral miRNAs target genes involved in interferon signaling pathway.

The infected cell detects the viral PAMPs by various pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as RIG-I and trigger the secretion of interferons. Once secreted, the interferons bind to their receptor and stimulates the expression of hundreds of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs), which coordinate to achieve an antiviral state by cell. Various viral miRNAs (shown in red) block different genes of interferon pathway.

Table 1.

List of viral miRNA target genes involved in interferon pathway.

| Viral miRNA | Virus | Target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-BART-1-5p | Epstein Barr Virus | LMP1 | 60 |

| miR-BART16 | Epstein Barr Virus | LMP1 | 60 |

| miR-BART17-5p | Epstein Barr Virus | LMP1 | 60 |

| miR-BART3 | Epstein Barr Virus | LMP1 | 61 |

| miR-BART5 | Epstein Barr Virus | LMP1 | 62, 63 |

| miR-BART22 | Epstein Barr Virus | LMP2A | 65, 66 |

| miR-BART8 | Epstein Barr Virus | STAT1 | 67 |

| miR-BART20-5p | Epstein Barr Virus | IFN-y | 67 |

| miR-BART16 | Epstein Barr Virus | CBP | 68 |

| miR-BART6-3p | Epstein Barr Virus | RIG-I | 70 |

| miR-UL112 | Human Cytomegalovirus | IRF1 | 71 |

| TTVtth8-miR-T1 | Torque teno virus | NMI | 76 |

| Zebov-miR-1-5p | Ebola Virus | Karyopherin-α1 (Importin-α5) | 77 |

4.1. Epstein Barr Virus

The herpesvirus family encode viral miRNAs and more than 90% of the characterized viral miRNAs are from the members of herpesvirus family [52]. Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) is the first virus known to encode miRNAs [53]. The EBV encoded miRNAs are located in two clusters, the BamHI fragment A rightward transcript (BART) cluster and the BamHI fragment H rightward open reading frame 1 (BHRF1) cluster in viral genome. The BART cluster generates 22 miRNA precursors, which produce 40 mature miRNAs and the BHRF1 cluster generates 3 miRNA precursors which produce 4 mature miRNA sequences. The EBV encoded miRNAs can target host mRNAs as well as viral mRNAs [54].

Latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) is a membrane protein expressed by EBV. LMP1 acts as a functional homolog of CD40 [55], constitutively active TNF receptor [56] and known to stimulate multiple signaling pathways such as NFκB [57], Janus Kinase / Signal Transducer And Activator Of Transcription (JAK/STAT) and Phospholipase C/Protein Kinase C (PLC/PKC) pathway to regulate the expression of various proteins related to antiviral immune response. LMP1 is also known to activate interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) by promoting receptor-interacting protein (RIP) dependent K-63 ubiquitination of IRF7, which is a pre-requisite for phosphorylation and activation of IRF7 [58]. Lo et al. employed luciferase reporter assays to show that miR-BART-1–5p, miR-BART16, miR-BART17–5p encoded by EBV directly target LMP1 3′UTR and significantly reduced the luciferase activity of their target reporters. Overexpression of these miRNAs in CNE1-EBV (Nasopharyngeal carcinoma derived EBV negative cell line) cells significantly reduced the endogenous levels of LMP1 protein and the transfection of antisense oligos of these v - miRs resulted in the increased expression of LMP1 [59]. In other studies, miR-BART3 and miR-BART5 were also reported to target LMP1 [60–62]. In contrast to the above-mentioned miRNAs, miR-BART9 positively regulate the expression of LMP1 by maintaining the stability of its mRNA. Although miR-BART9 does not directly target LMP1, its overexpression increased the levels of LMP1 protein, while the inhibition of miR-BART-9 led to a reduction of LMP1 protein [63]. Another study showed that miR-BART22 targets LMP2A, another protein encoded by EBV implicated in the regulation of interferon response by targeting the interferon receptors for degradation [64, 65].

Huang et al. showed that miR-BART8 and miR-BART20–5p inhibit the IFN-γ-STAT1 signaling pathway and promote the progression of nasal NK cell lymphoma. They cloned 22 stem-loop miRNA precursor of BART family and screened them for binding 3′UTR of IFN-γ using luciferase reporter assay. Of these 22, miR-BART20–5p precursor showed the most prominent reduction in luciferase activity in Jurkat cells (derived from an EBV negative T-cell lymphoma). In a similar screening, miR-BART8 precursor was shown to target STAT1 3′UTR [66].

miR-BART16 suppresses the type I interferon signaling by directly targeting and downregulating the CREB binding protein (CREBBP or CBP), which is a well characterized transcriptional co-activator of IFN signaling [67]. CBP is a transcriptional co-activator (histone acetyltransferase), which together with p300 (another histone acetyltransferase) interact with various transcription factor and form multimeric complex on respective promotors. Suhara et al. have shown that CBP directly binds to phosphorylated IRF3 homodimer, which is a critical activator of type 1 interferon system [68].

RIG-I (Retinoic acid-inducible gene I) is a member of cytosolic DExD/H box RNA helicases (others are MDA5 and LGP2). The activation of RIG-I and downstream signaling induce the induction of type 1 interferons. RIG-1 and MDA5 detect RNA derived from viruses in the cytoplasm. miR-BART6–3p directly binds to the 3′UTR of RIG-I and inhibit the RLR signaling and type 1 interferon response [69].

4.2. Human Cytomegalovirus

Beta herpesvirus Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) employs miRNA to inhibit the interferon response. Huang et al. showed that HCMV-miR-UL112 downregulates type I interferon. They stably expressed HCMV-miR-UL112 in PBMCs from healthy human donors and stimulated with poly (I:C) and measured secreted IFN-α and IFN-β protein levels by ELISA. Decreased IFN-α and IFN-β levels were observed in HCMV-miR-UL112 expressing PBMCs stimulated with Poly (I:C) compared to control transfected or uninduced PBMCs [70]. This study did not discuss the mode of action of HCMV-miR-UL112 in regulating the IFN production, but a previous study identified IRF1 (Interferon regulatory factor 1) as a target of HCMV-miR-UL112 [71]. IRF1 is a member of interferon regulatory factor family and regulates the expression of interferon by binding to interferon stimulated response element (ISRE) in the promoters of interferons.

4.3. Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) or HHV-8 is a gamma herpesvirus, known to cause Kaposi’s sarcoma. KSHV encodes 13 pre-miRNAs, resulting in 25 mature miRNAs. Liang et al. used DIANA microT v3.0 web server to predict the potential targets for KSHV encoded miR-K12–11 and found IKKɛ (I-kappa-B kinase epsilon), a non-canonical IKK as a potential target. IKKɛ is an important modulator of IFN signaling pathway. It phosphorylates and activates IRF3 and IRF7. IKKɛ is also known to activate a subset of ISGs (IKKɛ−dependent ISGs). Using luciferase reporter assays authors successfully validated that the IKKɛ is a genuine target of miR-K12–11. Overexpression of miR-K12–11 decreased the endogenous as well as exogenously expressed IKKɛ protein. Decreased levels of IKKɛ resulted in decreased IRF3/IRF7 phosphorylation and inhibition of IKKɛ−dependent ISGs thereby favoring viral survival [72].

4.4. Torque Teno Viruses

Torque teno viruses (TTVs) are members of Anelloviridae with small single stranded circular DNA genomes of approximately 3.8 kilobases (kb) [73]. The first TTV viral sequence was isolated from the serum of a patient with post-transfusion hepatitis of unknown (non-A-G hepatitis) etiology [74]. Although TTV are ubiquitously present in humans, to date, no human pathogenicity has been established and no causal disease associations are known [75].

Kincaid et al. used a combined computational and synthetic approach to predict miRNA coding regions in diverse human TTVs. They identified 16 host mRNA targets in microarray analysis of RNA from HEK293TT cells (HEK293 cell overexpressing large T antigen of SV40) transfected with TTV-tth8 viral genome. These 16 targets were downregulated in TTV-tth8 transfected cells compared to TTV-MUT (does not produce TTV-tth8-miR-T1) or vector control transfected cells. These targets were also predicted to have TTVtth8-miR-T1 binding sites (complementary sequence to TTVtth8-miRT1 seed sequence) in their 3′UTR. They chose NMI (N-myc and STAT interactor), an interferon stimulated gene (ISG) and regulator of STAT signaling for further validation. Using NMI 3′ UTR reporter luciferase constructs, they showed that TTVtth8-miR-T1 directly binds to and targets NMI mRNA. Transfection of TTVtth8-miR-T1 mimic in Hela cells resulted in down-regulation of NMI protein [76].

4.5. Ebola Virus

The Ebolavirus, a negative sense RNA virus belongs to Filoviridae family was first identified in 1976 in Sudan. Four species in the genus Ebolavirus are known to cause disease in humans and primates. Liu et al. carried out bioinformatics analysis to identify 24 sequences in Ebolavirus genome with potential stem-loop structures. They identified one putative miRNA coding precursor with relatively high prediction score and named it as Zebov-miR-1. Zebov-miR-1 was predicted to have two mature miRNAs, Zebov-miR-1–5p and Zebov-miR-1–3p. They showed that Zebov-miR-1–5p targets karyopherin α1, which is an essential regulator of the host interferon response [77]. Karyopherins are the proteins which transport molecules between nucleus and cytoplasm through nuclear pore. They can act as importins (import proteins into the nucleus) or exportins (export proteins out of the nucleus) and bind to conserved sequence motifs present in their cargo proteins known as nuclear localization signal (NLS) and nuclear egress signal (NES), respectively [78]. Karyopherin-α1 (also known as Importin-α5) binds to NLS of STAT1 and facilitate its import into the nucleus after tyrosine phosphorylation by activated Janus Kinases (JAK) and dimerization [79, 80]. This leads to the transcription of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). Many viruses block the translocation of STATs to the nucleus by stimulating the degradation of Karyopherin-α1 to inhibit the expression of ISGs as a strategy to control the antiviral response mounted by host [81–84]. Earlier studies have also reported that Ebola virus VP24 protein binds to karyopherin-α1 and blocks its accumulation in the nucleus and inhibits the IFNα/β and IFNγ signaling [85]. Targeting of karyopherin-α1 by Zebov-miR-1–5p is another strategy by the Ebola virus to counter the host antiviral response. Liu et al also showed that Ebola virus encoded ZebovmiR-1–5p may act as an analog for the well-studied host miRNA hsa-miR-155–5p as it has similar seed sequence and may target the same mRNAs, which also include Importin-α5, suggesting the similar and important role of hsa-miR-155 during viral infection [77].

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Research in the field of host-virus interaction has identified various mechanisms that allow host and pathogen to thwart each other’s defense and counter defenses. Virus-encoded microRNAs are a recent addition to this everlasting battle. In the last decade, we have gained vast knowledge of biological functions that v-miRs perform and how that benefit virus. Identification of v-miR-mediated mechanisms indicate the significance of incorporating noncoding, regulatory RNA to have widespread impact on host as well as viral transcripts. Recent evidences demonstrate v-miR targeting of components of interferon pathway promotes immune evasion. Increasing evidences also indicate that v-miR levels are enhanced in disease and infection suggesting their critical role in pathogenesis. For example, v-miRs were detected in human dental pulp and gingival biopsies, where they may likely alter host cell transcriptome and regulate viral infection [48, 86, 87]. It will be interesting to study whether v-miRs frequently detected in disease have potent immunomodulatory functions. Utilizing v-miRs for diagnostics in diseases is another area that is relatively unexplored. Whether detection of a subset of v-miRs can yield significant clinical information needs to be verified. Nonetheless, few recent studies have hinted on the possibility of diagnostic potential of v-miRs. Last but not the least, employing the biological functions of v-miRs for therapeutic value in other non-viral, inflammatory diseases like autoimmune disorders is yet another research avenue. It will be interesting to monitor how research will progress in these yet uncharted territories. Nonetheless, given the diverse biological functions of v-miRs, these noncoding RNAs hold immense diagnostic and therapeutic potential.

FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Part of this work was funded by the NIH/NIDCR R01 DE027980, R21 DE026259-01A1 and R03 DE027147 to ARN.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

REFERENCES

- [1].Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature 2012; 482(7385): 331–8. [ 10.1038/nature10886] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rath D, Amlinger L, Rath A, Lundgren M. The CRISPR-Cas immune system: biology, mechanisms and applications. Biochimie 2015; 117: 119–28. [ 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.03.025] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Guo Z, Li Y, Ding SW. Small RNA-based antimicrobial immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2019; 19(1): 31–44. [ 10.1038/s41577-018-0071-x] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Blevins T, Rajeswaran R, Shivaprasad PV, et al. Four plant Dicers mediate viral small RNA biogenesis and DNA virus induced silencing. Nucleic Acids Res 2006; 34(21): 6233–46. [ 10.1093/nar/gkl886] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Secombes CJ, Zou J. Evolution of Interferons and Interferon Receptors. Front Immunol 2017; 8: 209 [ 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00209] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Katze MG, He Y, Gale M Jr. Viruses and interferon: a fight for supremacy. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2(9): 675–87. [ 10.1038/nri888] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004; 116(2): 281–97. [ 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Naqvi AR, Islam MN, Choudhury NR, Haq QM. The fascinating world of RNA interference. Int J Biol Sci 2009; 5(2): 97–117. [ 10.7150/ijbs.5.97] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Plaisance-Bonstaff K, Renne R. Viral miRNAs. Methods Mol Biol 2011; 721: 43–66. [ 10.1007/978-1-61779-037-9_3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Naqvi AR. Immunomodulatory roles of human herpesvirusencoded microRNA in host-virus interaction. Rev Med Virol 2019e2081 [ 10.1002/rmv.2081] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W. Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu Rev Biochem 2010; 79: 351–79. [ 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Naqvi AR, Shango J, Seal A, Shukla D, Nares S. Herpesviruses and MicroRNAs: New Pathogenesis Factors in Oral Infection and Disease? Front Immunol 2018; 9: 2099 [ 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02099] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Diagnostic Auvinen E. and Prognostic Value of MicroRNA in Viral Diseases. Mol Diagn Ther 2017; 21(1): 45–57. [ 10.1007/s40291-016-0236-x] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fan C, Tang Y, Wang J, et al. The emerging role of Epstein-Barr virus encoded microRNAs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cancer 2018; 9(16): 2852–64. [ 10.7150/jca.25460] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang JM, An J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2007; 45(2): 27–37. [ 10.1097/AIA.0b013e318034194e] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Isaacs A, Lindenmann J. Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1957; 147(927): 258–67. [ 10.1098/rspb.1957.0048] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chen K, Liu J, Cao X. Regulation of type I interferon signaling in immunity and inflammation: A comprehensive review. J Autoimmun 2017; 83: 1–11. [ 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.03.008] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pestka S, Krause CD, Walter MR. Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol Rev 2004; 202: 8–32. [ 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00204.x] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Le Page C, Génin P, Baines MG, Hiscott J. Interferon activation and innate immunity. Rev Immunogenet 2000; 2(3): 374–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Parkin J, Cohen B. An overview of the immune system. Lancet 2001; 357(9270): 1777–89. [ 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04904-7] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Orchansky P, Novick D, Fischer DG, Rubinstein M. Type I and Type II interferon receptors. J Interferon Res 1984; 4(2): 275–82. [ 10.1089/jir.1984.4.275] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Uzé G, Schreiber G, Piehler J, Pellegrini S. The receptor of the type I interferon family. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2007; 316: 71–95. [ 10.1007/978-3-540-71329-6_5] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wack A, Terczyńska-Dyla E, Hartmann R. Guarding the frontiers: the biology of type III interferons. Nat Immunol 2015; 16(8): 802–9. [ 10.1038/ni.3212] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].O’Shea JJ, Schwartz DM, Villarino AV, Gadina M, McInnes IB, Laurence A. The JAK-STAT pathway: impact on human disease and therapeutic intervention. Annu Rev Med 2015; 66: 311–28. [ 10.1146/annurev-med-051113-024537] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Haan C, Kreis S, Margue C, Behrmann I. Jaks and cytokine receptors--an intimate relationship. Biochem Pharmacol 2006; 72(11): 1538–46. [ 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.013] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ragimbeau J, Dondi E, Alcover A, Eid P, Uzé G, Pellegrini S. The tyrosine kinase Tyk2 controls IFNAR1 cell surface expression. EMBO J 2003; 22(3): 537–47. [ 10.1093/emboj/cdg038] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Schindler C, Shuai K, Prezioso VR, Darnell JE Jr. Interferondependent tyrosine phosphorylation of a latent cytoplasmic transcription factor. Science 1992; 257(5071): 809–13. [ 10.1126/science.1496401] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Heim MH, Kerr IM, Stark GR, Darnell JE Jr. Contribution of STAT SH2 groups to specific interferon signaling by the Jak- STAT pathway. Science 1995; 267(5202): 1347–9. [ 10.1126/science.7871432] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Levy DE, Darnell JE Jr. Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002; 3(9): 651–62. [ 10.1038/nrm909] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fu XY, Kessler DS, Veals SA, Levy DE, Darnell JE Jr. ISGF3, the transcriptional activator induced by interferon α, consists of multiple interacting polypeptide chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87(21): 8555–9. [ 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8555] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schindler C, Fu XY, Improta T, Aebersold R, Darnell JE Jr. Proteins of transcription factor ISGF-3: one gene encodes the 91- and 84-kDa ISGF-3 proteins that are activated by interferon α. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992; 89(16): 7836–9. [ 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7836] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shuai K, Schindler C, Prezioso VR, Darnell JE Jr. Activation of transcription by IFN-gamma: tyrosine phosphorylation of a 91- kD DNA binding protein. Science 1992; 258(5089): 1808–12. [ 10.1126/science.1281555] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Decker T, Lew DJ, Mirkovitch J, Darnell JE Jr. Cytoplasmic activation of GAF, an IFN-gamma-regulated DNA-binding factor. EMBO J 1991; 10(4): 927–32. [ 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08026.x] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Decker T, Kovarik P, Meinke A. GAS elements: a few nucleotides with a major impact on cytokine-induced gene expression. J Interferon Cytokine Res 1997; 17(3): 121–34. [ 10.1089/jir.1997.17.121] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Huang J, Wang F, Argyris E, et al. Cellular microRNAs contribute to HIV-1 latency in resting primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat Med 2007; 13(10): 1241–7. [ 10.1038/nm1639] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ahluwalia JK, Khan SZ, Soni K, et al. Human cellular microRNA hsa-miR-29a interferes with viral nef protein expression and HIV-1 replication. Retrovirology 2008; 5: 117 [ 10.1186/1742-4690-5-117] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific MicroRNA. Science 2005; 309(5740): 1577–81. [ 10.1126/science.1113329] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kasschau KD, Xie Z, Allen E, et al. P1/HC-Pro, a viral suppressor of RNA silencing, interferes with Arabidopsis development and miRNA unction. Dev Cell 2003; 4(2): 205–17. [ 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00025-X] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Aqil M, Naqvi AR, Bano AS, Jameel S. The HIV-1 Nef protein binds argonaute-2 and functions as a viral suppressor of RNA interference. PLoS One 2013; 8(9)e74472 [ 10.1371/journal.pone.0074472] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Aqil M, Naqvi AR, Mallik S, Bandyopadhyay S, Maulik U, Jameel S. The HIV Nef protein modulates cellular and exosomal miRNA profiles in human monocytic cells. J Extracell Vesicles 2014; 3: 3 [ 10.3402/jev.v3.23129] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sullivan CS, Ganem D. A virus-encoded inhibitor that blocks RNA interference in mammalian cells. J Virol 2005; 79(12): 7371–9. [ 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7371-7379.2005] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Moore PS, Boshoff C, Weiss RA, Chang Y. Molecular mimicry of human cytokine and cytokine response pathway genes by KSHV. Science 1996; 274(5293): 1739–44. [ 10.1126/science.274.5293.1739] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Slobedman B, Barry PA, Spencer JV, Avdic S, Abendroth A. Virus-encoded homologs of cellular interleukin-10 and their control of host immune function. J Virol 2009; 83(19): 9618–29. [ 10.1128/JVI.01098-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Vieira P, de Waal-Malefyt R, Dang MN, et al. Isolation and expression of human cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor cDNA clones: homology to Epstein-Barr virus open reading frame BCRFI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991; 88(4): 1172–6. [ 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1172] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Thurmond S, Wang B, Song J, Hai R. Suppression of Type I Interferon Signaling by Flavivirus NS5. Viruses 2018; 10(12)E712 [ 10.3390/v10120712] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ronco LV, Karpova AY, Vidal M, Howley PM. Human papillomavirus 16 E6 oncoprotein binds to interferon regulatory factor-3 and inhibits its transcriptional activity. Genes Dev 1998; 12(13): 2061–72. [ 10.1101/gad.12.13.2061] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Neznanov N, Chumakov KM, Neznanova L, Almasan A, Banerjee AK, Gudkov AV. Proteolytic cleavage of the p65-RelA subunit of NF-kappaB during poliovirus infection. J Biol Chem 2005; 280(25): 24153–8. [ 10.1074/jbc.M502303200] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Naqvi AR, Seal A, Shango J, et al. Herpesvirus-encoded microRNAs detected in human gingiva alter host cell transcriptome and regulate viral infection. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 2018; 1861(5): 497–508. [ 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.03.001] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Naqvi AR, Shango J, Seal A, Shukla D, Nares S. Viral miRNAs alter host cell miRNA profiles and modulate innate immune responses. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 433 [ 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00433] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Han Z, Liu X, Chen X, et al. miR-H28 and miR-H29 expressed late in productive infection are exported and restrict HSV-1 replication and spread in recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113(7): E894–901. [ 10.1073/pnas.1525674113] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Yogev O, Henderson S, Hayes MJ, et al. Herpesviruses shape tumour microenvironment through exosomal transfer of viral microRNAs. PLoS Pathog 2017; 13(8)e1006524 [ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006524] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Fiorucci G, Chiantore MV, Mangino G, Romeo G. MicroRNAs in virus-induced tumorigenesis and IFN system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2015; 26(2): 183–94. [ 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.11.002] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Pfeffer S, Zavolan M, Grässer FA, et al. Identification of virusencoded microRNAs. Science 2004; 304(5671): 734–6. [ 10.1126/science.1096781] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kim DN, Lee SK. Biogenesis of Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs. Mol Cell Biochem 2012; 365(1–2): 203–10. [ 10.1007/s11010-012-1261-7] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Pratt ZL, Zhang J, Sugden B. The latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) oncogene of Epstein-Barr virus can simultaneously induce and inhibit apoptosis in B cells. J Virol 2012; 86(8): 4380–93. [ 10.1128/JVI.06966-11] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Cameron JE, Yin Q, Fewell C, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces cellular MicroRNA miR-146a, a modulator of lymphocyte signaling pathways. J Virol 2008; 82(4): 1946–58. [ 10.1128/JVI.02136-07] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ersing I, Bernhardt K, Gewurz BE. NF-κB and IRF7 pathway activation by Epstein-Barr virus Latent Membrane Protein 1. Viruses 2013; 5(6): 1587–606. [ 10.3390/v5061587] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Huye LE, Ning S, Kelliher M, Pagano JS. Interferon regulatory factor 7 is activated by a viral oncoprotein through RIP-dependent ubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol 2007; 27(8): 2910–8. [ 10.1128/MCB.02256-06] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lo AK, To KF, Lo KW, et al. Modulation of LMP1 protein expression by EBV-encoded microRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104(41): 16164–9. [ 10.1073/pnas.0702896104] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Riley KJ, Rabinowitz GS, Yario TA, Luna JM, Darnell RB, Steitz JA. EBV and human microRNAs co-target oncogenic and apoptotic viral and human genes during latency. EMBO J 2012; 31(9): 2207–21. [ 10.1038/emboj.2012.63] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Skalsky RL, Corcoran DL, Gottwein E, et al. The viral and cellular microRNA targetome in lymphoblastoid cell lines. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8(1)e1002484 [ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002484] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Skalsky RL, Kang D, Linnstaedt SD, Cullen BR. Evolutionary conservation of primate lymphocryptovirus microRNA targets. J Virol 2014; 88(3): 1617–35. [ 10.1128/JVI.02071-13] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ramakrishnan R, Donahue H, Garcia D, et al. Epstein-Barr virus BART9 miRNA modulates LMP1 levels and affects growth rate of nasal NK T cell lymphomas. PLoS One 2011; 6(11)e27271 [ 10.1371/journal.pone.0027271] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Lung RW, Tong JH, Sung YM, et al. Modulation of LMP2A expression by a newly identified Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA miR-BART22. Neoplasia 2009; 11(11): 1174–84. [ 10.1593/neo.09888] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Shah KM, Stewart SE, Wei W, et al. The EBV-encoded latent membrane proteins, LMP2A and LMP2B, limit the actions of interferon by targeting interferon receptors for degradation. Oncogene 2009; 28(44): 3903–14. [ 10.1038/onc.2009.249] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Huang WT, Lin CW. EBV-encoded miR-BART20–5p and miRBART8 inhibit the IFN-γ-STAT1 pathway associated with disease progression in nasal NK-cell lymphoma. Am J Pathol 2014; 184(4): 1185–97. [ 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.12.024] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Hooykaas MJG, van Gent M, Soppe JA, et al. EBV MicroRNA BART16 Suppresses Type I IFN Signaling. J Immunol 2017; 198(10): 4062–73. [ 10.4049/jimmunol.1501605] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Suhara W, Yoneyama M, Kitabayashi I, Fujita T. Direct involvement of CREB-binding protein/p300 in sequence-specific DNA binding of virus-activated interferon regulatory factor-3 holocomplex. J Biol Chem 2002; 277(25): 22304–13. [ 10.1074/jbc.M200192200] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Lu Y, Qin Z, Wang J, et al. Epstein-Barr Virus miR-BART6–3p Inhibits the RIG-I Pathway. J Innate Immun 2017; 9(6): 574–86. [ 10.1159/000479749] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Huang Y, Chen D, He J, et al. Hcmv-miR-UL112 attenuates NK cell activity by inhibition type I interferon secretion. Immunol Lett 2015; 163(2): 151–6. [ 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.12.003] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Li S, Zhu J, Zhang W, et al. Signature microRNA expression profile of essential hypertension and its novel link to human cytomegalovirus infection. Circulation 2011; 124(2): 175–84. [ 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.012237] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Liang D, Gao Y, Lin X, et al. A human herpesvirus miRNA attenuates interferon signaling and contributes to maintenance of viral latency by targeting IKKε. Cell Res 2011; 21(5): 793–806. [ 10.1038/cr.2011.5] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].King AMQ, Lefkowitz E, Adams MJ, Carstens EB. Family - Anelloviridae In: King AMQ, Lefkowitz E, Carstens EB, Eds. Virus Taxonomy. 331–41. [Google Scholar]

- [74].Nishizawa T, Okamoto H, Konishi K, Yoshizawa H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. A novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with elevated transaminase levels in posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997; 241(1): 92–7. [ 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7765] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Hino S, Miyata H. Torque teno virus (TTV): current status. Rev Med Virol 2007; 17(1): 45–57. [ 10.1002/rmv.524] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Kincaid RP, Burke JM, Cox JC, de Villiers E-M, Sullivan CS. A human torque teno virus encodes a microRNA that inhibits interferon signaling. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9(12)e1003818 [ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003818] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [77].Liu Y, Sun J, Zhang H, Wang M, Gao GF, Li X. Ebola virus encodes a miR-155 analog to regulate importin-α5 expression. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016; 73(19): 3733–44. [ 10.1007/s00018-016-2215-0] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Chook YM, Blobel G. Karyopherins and nuclear import. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2001; 11(6): 703–15. [ 10.1016/S0959-440X(01)00264-0] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Fagerlund R, Mélen K, Kinnunen L, Julkunen I. Arginine/lysinerich nuclear localization signals mediate interactions between dimeric STATs and importin alpha 5. J Biol Chem 2002; 277(33): 30072–8. [ 10.1074/jbc.M202943200] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].McBride KM, Banninger G, McDonald C, Reich NC. Regulated nuclear import of the STAT1 transcription factor by direct binding of importin-alpha. EMBO J 2002; 21(7): 1754–63. [ 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1754] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Du Y, Bi J, Liu J, et al. 3Cpro of foot-and-mouth disease virus antagonizes the interferon signaling pathway by blocking STAT1/STAT2 nuclear translocation. J Virol 2014; 88(9): 4908–20. [ 10.1128/JVI.03668-13] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Melen K, Fagerlund R, Franke J, Kohler M, Kinnunen L, Julkunen I. Importin alpha nuclear localization signal binding sites for STAT1, STAT2, and influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J Biol Chem 2003l; 278(30): 28193–200. [ 10.1074/jbc.M303571200] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Wang C, Sun M, Yuan X, et al. Enterovirus 71 suppresses interferon responses by blocking Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling through inducing karyopherin-α1 degradation. J Biol Chem 2017; 292(24): 10262–74. [ 10.1074/jbc.M116.745729] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Wang R, Nan Y, Yu Y, Zhang YJ. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus Nsp1β inhibits interferon-activated JAK/STAT signal transduction by inducing karyopherin-α1 degradation. J Virol 2013; 87(9): 5219–28. [ 10.1128/JVI.02643-12] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Reid SP, Leung LW, Hartman AL, et al. Ebola virus VP24 binds karyopherin α1 and blocks STAT1 nuclear accumulation. J Virol 2006; 80(11): 5156–67. [ 10.1128/JVI.02349-05] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Zhong S, Naqvi A, Bair E, Nares S, Khan AA. Viral MicroRNAs Identified in Human Dental Pulp. J Endod 2017; 43(1): 84–9. [ 10.1016/j.joen.2016.10.006] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Naqvi AR, Brambila MF, Martínez G, Chapa G, Nares S. Dysregulation of human miRNAs and increased prevalence of HHV miRNAs in obese periodontitis subjects. J Clin Periodontol 2019; 46(1): 51–61. [ 10.1111/jcpe.13040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]