Abstract

A history of maltreatment in childhood may influence adults’ parenting practices, potentially affecting their children. This systematic review examines 97 studies investigating associations of parental childhood victimization with a range of parenting behaviors that may contribute to the intergenerational effects of abuse: abusive parenting, problematic parenting, positive parenting, and positive parental affect. Key findings include: (1) parents who report experiencing physical abuse or witnessing violence in the home during childhood are at increased risk for reporting that they engage in abusive or neglectful parenting; (2) a cumulative effect of maltreatment experiences, such that adults who report experiencing multiple types or repeated instances of victimization are at greatest risk for perpetrating child abuse; (3) associations between reported childhood maltreatment experiences and parents’ problematic role reversal with, rejection of, and withdrawal from their children; (4) indirect effects between reported childhood maltreatment and abusive parenting via adult intimate partner violence; and (5) indirect effects between reported childhood maltreatment and lower levels of positive parenting behaviors and affect via mothers’ mental health. Thus, childhood experiences of maltreatment may alter parents’ ability to avoid negative and utilize positive parenting practices. Limitations of this body of literature include few prospective studies, an overreliance on adults’ self-report of their childhood victimization and current parenting, and little examination of potentially differential associations for mothers and fathers.

Keywords: Childhood maltreatment, Parenting practices, Intergenerational transmission

1. Introduction

The impact of childhood abuse, neglect, and violence exposure on adult physical and emotional health and behaviors is significant and well documented (Anda et al., 2006; Hughes et al., 2017; Norman et al., 2012; Widom, Czaja, Bentley, & Johnson, 2012) including increases in the rate of PTSD, depression, and other mental health disorders; substance use; obesity; risky health behaviors; perceived stress and difficulty controlling one’s anger; and physical health problems (Anda et al., 2006; Widom, Horan, & Brzustowicz, 2015). Given the strong impact on adults’ affective and behavioral responses, it is not surprising that growing evidence suggests that childhood maltreatment experiences also affect parenting practices (Savage, Tarabulsy, Pearson, Collin-Vézina, & Gagné, 2019). While much of the literature focuses on the intergenerational transmission of abusive parenting practices, a growing body of research investigates associations with other parenting outcomes – both positive and negative. The goal of the current review is to examine associations among childhood maltreatment experiences (defined here as physical, sexual, or emotional abuse and neglect, and witnessing violence) and this full range of parenting behaviors. Doing so will shed light on the varied ways that the effects of parents’ childhood maltreatment experiences have an impact on their children in the next generation and inform the ways in which clinicians intervene to support children and families.

Given the significant toll that child maltreatment inflicts on its victims, there has been much interest in the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment, also referred to as the “cycle of violence,” or whether or not a parent’s experience of childhood maltreatment increases the risk that his or her child will also be maltreated, and thus perpetuate the harm. Child maltreatment has been operationalized over the years in numerous ways in the clinical and research literatures (Gardner, Thomas, & Erskine, 2019; Humphreys et al., 2020; Valentine, Acuff, Freeman, & Andreas, 1984). However, there is growing definitional consensus among recent studies and reviews consistent with the World Health Organization’s characterization, which describes child maltreatment as “all types of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence and commercial or other exploitation, which results in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power. Exposure to intimate partner violence is also sometimes included as a form of child maltreatment” (World Health Organization, 2016). Thus, within the context of this review, childhood maltreatment is characterized as the experience of physical, sexual or emotional abuse and/or neglect, as well as witnessing family violence.

Several narrative reviews over the past 30 years have evaluated the literature that addresses this question, frequently noting the limited methodological rigor of the contributing studies (e.g., Kaufman & Zigler, 1987; Ertem, Leventhal, and Dobbs, 2000; Thornberry, Knight, & Lovegrove, 2012). Thornberry et al. (2012), for example, evaluated 47 studies against a standard of 11 methodological criteria and noted significant shortcomings in the methodology of most of the studies, including an overwhelming reliance on retrospective recall of parental maltreatment, clinical rather than representative samples, and short follow-up periods to assess the child generation’s maltreatment experiences. The authors assessed that there was insufficient evidence to draw a firm conclusion regarding the cycle of maltreatment. Recently, Madigan et al. (2019) found modest associations (k = 80, d = 0.45, 95% CI [0.37, 0.54]) in a large, meta-analytic review of this body of literature and identified a moderating effect of methodological quality among the studies examining physical abuse (b = −.051, p < .05), for which the effect size decreased as methodological rigor increased.

In addition to the methodological shortcomings noted above, inconsistency in the definition of intergenerational trauma also contributes to the challenge of navigating this body of literature. Specifically, the literature tends to incorporate conceptualizations of intergenerational maltreatment that reflect the second generations’ maltreatment either including (1) experiences that occur at the hands of any adult (what Madigan et al. (2019) refers to as victim-to-victim transmission) or (2) only that which occurs at the hands of the maltreated parent (victim-to-perpetrator transmission). Although studies utilizing each of these definitions are often pooled together, conceptually they are distinct, though there may be overlap in risk factors. We are interested in examining the range of parenting behaviors in which adults who were maltreated as children engage, and therefore within the abusive parenting category of this review we include only studies examining victim-to-perpetrator transmission.

Given the modest associations in support of the cycle of maltreatment, a synthesis is also needed of the literature that examines the impact of childhood maltreatment on a wider range of parenting behaviors, spanning from behaviors that are problematic but not abusive, to lower levels of behaviors more typically considered positive. Compromised parenting behaviors (such as role reversal and rejecting, controlling, permissive, or intrusive behaviors) and reduced positive parenting behaviors (such as decreased use of consistent discipline or limit-setting) are likely much more common outcomes, given evidence that the majority of adults maltreated as children do not perpetrate maltreatment with their own children (Augustyn, Thornberry, & Henry, 2019; Egeland, Jacobvitz, & Sroufe, 1988; Kaufman & Zigler, 1987). Though less extreme than maltreatment, these other forms of compromised parenting are also associated with increased risk for negative social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes among children (Gershoff, Lansford, Sexton, Davis-Kean, & Sameroff, 2012; Kawabata, Alink, Tseng, van IJzendoorn, & Crick, 2011; Pinquart, 2017; Prevatt, 2003). In a small subset of studies, problematic but non-abusive parenting practices or characteristics (e.g., hostility or low parenting confidence) have been found to mediate the association between maternal childhood maltreatment and child psychopathology (Plant et al., 2017).

While negative parenting outcomes are most frequently examined, reduced positive parenting outcomes can also have detrimental effects on children (Kawabata et al., 2011; Serbin, Kingdon, Ruttle, & Stack, 2015; Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon, & Lengua, 2000). Although parenting behaviors occur on a continuum of more or less competent skills, the limited use of positive strategies and sensitive interactions should not be equated with the use of negative parenting behaviors, and vice versa. Parents’ childhood maltreatment experiences may affect one category of parenting behaviors but not the other, reflecting differing developmental processes. Therefore, they should be examined separately. Finally, given the well-documented benefits and protective effects of positive parenting on child outcomes (Eshel, Daelmans, Cabral De Mello, & Martines, 2006; Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 1997; Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein, & Winslow, 2015), a close examination of its association with parents’ childhood experiences is warranted.

A recent meta-analysis (Savage et al., 2019) examined the association between childhood maltreatment and subsequent parenting among 32 studies of mothers of children ages 0 to 6 years old. Parenting outcome measures were categorized into positive, negative or potentially abusive, and relationship-based (e.g., bonding). A small association between childhood maltreatment and parenting was found to be moderated by the type of parenting examined, with the weakest effects for positive parenting (r = −.07) and stronger, but still small, effects for negative and relationship-based parenting behaviors (r = −.15 and −.20 respectively). While this review examined an impressive breadth of parenting behaviors among women who have experienced childhood maltreatment, several important gaps remain to be addressed. First, in Savage et al.’s review, a wide range of behavioral and affective outcomes fell into the positive and negative parenting categories, but a finer-grained analysis is needed that distinguishes amongst abusive parenting, problematic parenting behaviors, positive parenting behaviors, and positive parental affect. Additionally, a number of negative parenting behaviors, such as inconsistent discipline or permissiveness, were not included in Savage et al.’s review. Second, Savage et al. focused solely on maternal parenting of children ages 0–6 years old. It is important to consider the impact of parents’ childhood maltreatment on children in the school years and adolescence, as well as studies including fathers. Finally, while the meta-analytic approach facilitated a quantitative analysis of the results of the included studies, as well as examination of a number of moderators, it precluded the examination of indirect effects that might help to further explain the transmission of maltreatment across generations.

The current systematic narrative review therefore examines the extensive literature base that investigates associations among parental childhood maltreatment experiences and a full range of parenting behaviors and children’s ages. The framework of the systematic review also allows us to address a wider range of studies (e.g., those with different study designs or insufficient statistical data included in the manuscript), populations (e.g., mothers as well as fathers, parents who participated in interventions), and outcomes (e.g., varied parenting behaviors). Results are discussed within four primary parenting categories: abusive parenting, problematic parenting behaviors, positive parenting behaviors, and positive parental affect. In addition to reviewing the direct effects of parental childhood interpersonal traumatic experiences on multiple domains of parenting, when included studies examined moderators or mediators, these findings are also noted.

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of publications

Methodology for the current systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2015). Relevant studies were identified by searching the on-line databases PsycInfo and PubMed, by examining the reference lists of articles found in the initial search, and from suggestions from colleagues with expertise in the field. For each database, the following search terms were used: child* (trauma OR maltreatment OR abuse) and parent* (style OR behavior OR practice OR skills OR discipline). The same search was also run in each database replacing parent* with caregiv*. Asterisks were used to ensure that all versions of the word were included [i.e., child or children; parent, parents, or parenting]. This search strategy was developed by the project team. An initial search was conducted in April 2015, and then updated in June 2017 and May 2019 following identical search and coding procedures (described below).

Articles were reviewed by CG, CW or LH, with 10% of articles reviewed by all three authors to check for fidelity to the coding criteria at each phase of the review process; author coding assignments were in agreement 88% of the time and disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. An initial review of titles and abstracts was conducted to determine if the following inclusion criteria were met: (a) the sample included a parent; (b) parent’s childhood maltreatment experiences (defined as physical abuse or neglect, sexual abuse, emotional abuse or neglect, witnessing family violence) were assessed; (c) at least one positive or negative parenting behavior was assessed; (d) the manuscript described an empirical study; (e) an association between parental childhood maltreatment and parenting was evaluated; (f) the manuscript was published in a peer-reviewed journal and available in English. To allow for the broadest possible selection of articles, we did not limit the age of second-generation children, the length of time for follow-up of parenting outcomes, or the population (community versus clinical samples). Nor did we limit the methodology by which maltreatment or parenting was assessed which introduces some heterogeneity into our sample. For example, some studies evaluated childhood maltreatment using well-established surveys (e.g., the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire), while others utilized 1 or more study-designed questions. Similarly, parenting assessments ranged from self-report questionnaires to observed parent-child interactions. Where relevant, these methodological limitations are noted in the discussion of results. Exclusion criteria included: (a) nonempirical publications, such as narrative or meta-analytic reviews, theoretical papers, or case studies; (b) qualitative studies; (c) studies that used only attitudes toward abuse or measures of child abuse potential, but not perpetration, as the outcome variable; (d) and studies that included abuse perpetrated by adults other than the maltreated parent as the outcome variable (a victim-to-victim conceptualization).

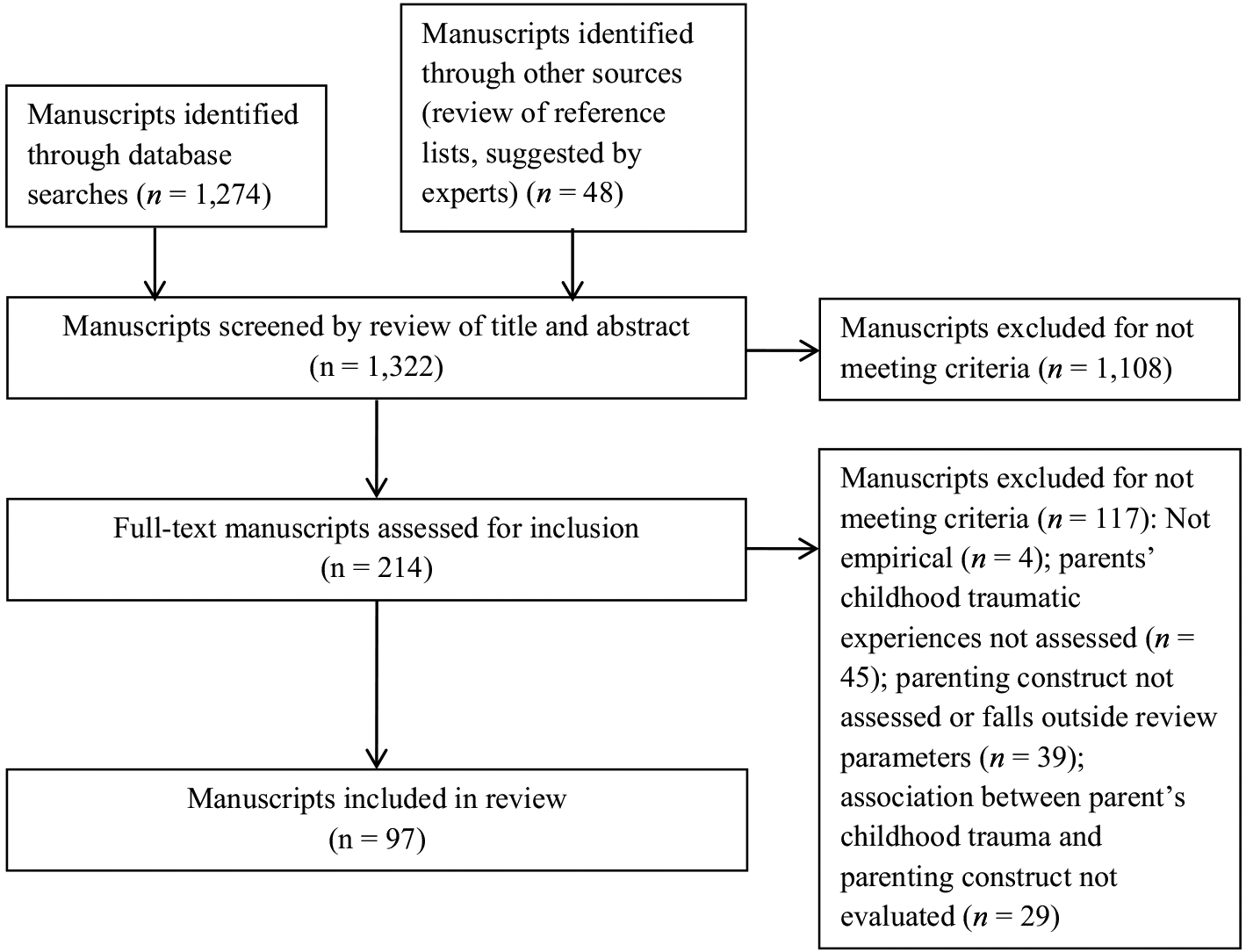

Based on these inclusion and exclusion criteria, 1,274 articles were identified through the search of electronic databases, and an additional 48 articles were identified through review of reference lists and suggestions from colleagues with expertise in this area (see Fig. 1). These results were uploaded into Mendeley where they were coded following each round of review. An initial screen of titles and abstracts identified 1,108 articles that did not meet criteria. A more thorough, full-text review was conducted of the remaining 214 articles and yielded a final set of 97 articles; 45 were excluded because parent’s childhood maltreatment was not assessed or fell outside the definition; 39 were excluded because a parenting construct was not assessed or fell outside the definition; 29 articles did not evaluate an association between parent’s childhood maltreatment and a parenting construct; and 4 were not empirical.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of identified studies.

For each of the 97 included articles, reviewers recorded sample descriptions, assessment measures and reporters, types of childhood maltreatment assessed, parenting constructs assessed, the inclusion of any moderators or mediators, and the results. Based on the parenting constructs, the first author assigned each article to the four parenting categories (abusive parenting, problematic parenting behaviors, positive parenting behaviors, and positive parental affect), utilizing multiple categories when appropriate (please see the Appendix for the parenting constructs identified and review categories assigned for each article).

2.2. Quality assessment

The 97 included articles were evaluated for quality by CG, LH, and CW using 7 criteria adapted from (Hoppen and Chalder, 2018) and the (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, n.d)National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (n.d.) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Twenty percent of articles were evaluated by all 3 authors with 92% agreement on the scoring elements. The following categories were assessed (with score range): study design (1–3), sample description and sampling procedures (0–2), operationalization of the child maltreatment variable (0–3), operationalization of the parenting behavior variable(s) (0–3), operationalization of moderator or mediator variables (if applicable; 0–1), assessment of single or multiple types of childhood maltreatment (0–1), use of appropriate statistical analyses with presentation of sufficient information (0–2). To address the variation in total scores due to not all studies including a mediator or moderator, scores were summed, divided by the possible total score, and multiplied by 100 to create a final percentage score, following the approach of Hoppen & Chalder (2018). Total scores have been added to the table in the Appendix and were distributed throughout the potential score range (M = 59.1, SD = 16.0). Lower scores primarily reflect the common occurrence of cross-sectional studies utilizing retrospective self-reports of childhood maltreatment, as the maximum score possible for this study design was 66%. Additional limitations in the literature base identified by the quality assessment were the frequent use of self-reported parenting behaviors and unvalidated assessment measures. A description of the scoring system and the detailed quality assessment results are available as supplementary material.

3. Results

Of the 97 included articles that evaluated associations between childhood traumatic experiences and at least one of the focal aspects of parenting, 46 articles examined abusive parenting, 28 articles examined problematic parenting behaviors, 12 articles examined positive parenting behaviors, and 23 examined positive parenting affect. A narrative synthesis of the findings of these studies follows below, organized by relevant subthemes within each parenting category. Although not a primary focus of this literature review, in addition to parenting behaviors and styles, other domains of parenting were often included in the identified articles. Two of the most commonly included domains, parenting stress (8 articles) and parenting self-perceptions (14 articles), are also discussed briefly in this review.

3.1. Abusive and neglectful parenting

Forty-six articles examined the association between parents’ own childhood maltreatment experiences and their subsequent maltreating behaviors toward their offspring. In summarizing this large body of literature, we have highlighted key issues that have not been addressed in previous reviews: unique versus cumulative effects, prospective analyses, inclusion of fathers, and examination of moderators and mediators.

3.1.1. Unique effect models

Seventeen articles assessed only a single form of childhood victimization, all but two of which examined the intergenerational transmission of childhood physical punishment or abuse, ranging from experiences of corporal punishment to severe physical violence (Capaldi, Tiberio, Pears, Kerr, & Owen, 2019; Coohey & Braun, 1997; Crombach & Bambonyé, 2015; Cuartas, Grogan-Kaylor, Ma, & Castillo, 2019; Deb & Adak, 2006; Ellonen, Peltonen, Poso, & Janson, 2017; Frias-Armenta, 2002; Hellmann, Stiller, Glaubitz, & Kliem, 2018; Hemenway, Solnick, & Carter, 1994; Herrenkohl, Klika, Brown, Herrenkohl, & Leeb, 2013; Jiang, Chen, Yu, & Jin, 2017; Muller, 1995; Pears & Capaldi, 2001; Peltonen, Ellonen, Poso, & Lucas, 2014; Simons, Whitbeck, Conger, & Wu, 1991). Although varied in their operationalization and methodological rigor, across these studies researchers consistently found that parents who reported experiencing physical abuse in childhood were more likely than non-abused parents to report engaging in physically aggressive behaviors toward their child. Likewise, physically abusive parents were more likely to report childhood physical abuse (CPA) experiences than non-abusive parents.

A limitation of all these studies is the fact that they did not control for other, co-occurring, experiences of childhood maltreatment. However, a similar pattern of potential intergenerational transmission was found among studies that examined unique effects while including other types of childhood abuse as covariates. Three studies of relatively large community samples found an association between reported experiences of past CPA and the use of physical punishment when other types of maltreatment and sociodemographic risk factors were included in the model (Barrett, 2009, 2010; Cappell & Heiner, 1990; Umeda, Kawakami, Kessler, & Miller, 2015)

Findings were mixed for the impact of childhood sexual abuse (CSA). Kim, Pears, Fisher, Connelly, and Landsverk (2010) found a small inverse relationship between mothers’ reported CSA experiences and their use of punitive discipline. Although Schuetze and Eiden (2005) found a relationship between retrospectively reported CSA and varied forms of discipline, they used a composite outcome measure that included physical abuse, as well as less severe forms of harsh discipline, the majority of which would not be considered maltreatment, and thus conclusions regarding the cycle of violence are inconclusive due to the multifaceted measurement of the outcome variable. Using a more robust semi-structured interview, Zvara, Mills-Koonce, & Cox (2017) found no differences in child-directed physical aggression between a group of mothers with childhood sexual trauma experiences and a group of matched controls. Controlling for CPA and neglect, Banyard (1997) found a positive association between CSA and the use of physical punishment among a sample of low-income women that included women referred to child protective services (CPS) and matched controls. Examining only the non-CPS referred women in this dataset, Zuravin and Fontanella (1999) found that CSA was no longer associated with severe violence by mothers toward their children after other childhood experiences were included in the model, suggesting that the relationship between past sexual abuse and subsequent violent parenting may hold only for child protection-referred samples of mothers. In contrast, Collin-Vézina, Cyr, Pauzé, and McDuff (2005) found no association between maternal CSA and use of physical punishment among 93 Canadian mothers referred to youth protection services.

Jackson et al. (1999) identified a unique effect of witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV) on the use of physical discipline among a community sample of parents. Others found similar associations between witnessing IPV as a child and use of physical discipline (Al Dosari, Ferwana, Abdulmajeed, Aldossari, & Al-Zahrani, 2017; Barrett, 2009; Cappell & Heiner, 1990; Fulu et al., 2017; Heyman & Slep, 2002). Among a large, nationally representative sample, mothers who experienced both physical abuse and witnessed IPV were twice as likely to physically abuse their children compared to mothers who experienced just one form of violence (Heyman & Slep, 2002).

Neglect is by far the most commonly substantiated form of maltreatment (Thornberry et al., 2012). Four studies examined the association of parents’ childhood abuse experiences with their subsequent neglect of their children, finding that a history of sexual abuse, physical abuse or having a violent parent was associated with neglectful parenting (Ethier, Lacharité, & Couture, 1995; Kim, 2009; Libby, Orton, Beals, Buchwald, & Manson, 2008; Zuravin & DiBlasio, 1992). Although amongst a small sample of low-income adolescent mothers, neglectful mothers were not more likely than non-neglectful mothers to report having been neglected or beaten (Zuravin & DiBlasio, 1992), in a large, nationally representative community sample adolescent mothers with a history of childhood neglect were 2.6 times more likely to report neglectful parenting than those who did not, controlling for other risk factors, including having been physically abused (Kim, 2009). Further, neglecting mothers were also found to have experienced more physical abuse by a greater number of people, to have been more likely to experience rape, or to have a mother involved in prostitution, as compared to non-neglecting mothers (Ethier et al., 1995).

3.1.2. Cumulative risk models

Strong evidence emerged in support of the cumulative impact of multiple types of child victimization and/ or repeated instances of maltreatment in childhood. Studies in which the additive effects of multiple maltreatment experiences were examined consistently indicated that a history of childhood abuse, neglect, and/or interparental violence was associated with greater likelihood of perpetrating physical abuse or neglect on one’s children (Banyard, Williams, & Siegel, 2003; Ben-David, 2016; Chung et al., 2009; L. R. Cohen, Hien, & Batchelder, 2008; Dubowitz et al., 2001; Ferrari, 2002; Frías-Armenta & McCloskey, 1998; Fulu et al., 2017; Heyman & Slep, 2002; Jackson et al., 1999; Kim, Pears, et al., 2010; Kim, Trickett, & Putnam, 2010; Milaniak & Widom, 2015). These findings held even after controlling for other child and adult risk factors (Ben-David, Jonson-Reid, Drake, & Kohl, 2015). Further, in cluster analysis, physically abusive parents tended to report greater levels of cumulative abuse histories compared with parents who scored low on the use of physical discipline (Thompson et al., 1999). In studies that examined the total effect of combined childhood abuse experiences amongst ethnically and socioeconomically diverse samples, a maternal history of childhood abuse was associated with harsh and punitive parenting and a greater likelihood of perpetrating child abuse (Cohen et al., 2008; Ferrari, 2002; Kim, 2009), with one exception in which no association was found in a small middle class Dutch sample in which no instances of severe maternal aggression were reported, suggesting the findings may have been limited by lack of variability in the data (Beckerman, van Berkel, Mesman, & Alink, 2017).

Several studies document a dose response in which multiple types of childhood victimization and/or repeated instances of maltreatment were associated with the greatest risk of adult perpetration (Ben-David et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2009; Dubowitz et al., 2001; Heyman & Slep, 2002). Indeed, Dubowitz et al. (2001) found evidence of a cumulative effect for both the type and timing of abusive experiences such that mothers who experienced physical or sexual abuse in both childhood and adulthood reported greater use of verbal aggression and minor violence tactics than mothers with abuse only in childhood, and mothers who experienced both types of victimization reported greater use of these aggressive tactics than mothers with only sexual abuse histories.

3.1.3. Prospective studies

A limitation of the studies reviewed to this point is that they have relied on adult parents’ retrospective reports of their experiences of past maltreatment or family violence in childhood. Recent evidence suggests that retrospective self-reports of maltreatment typically do not match contemporaneous records or reports, but instead may be better understood as a product of current circumstances and psychological state (White, Widom, & Chen, 2007; Widom, 2019). Six of the studies included prospective analyses of ethnically and socioeconomically diverse samples of children followed longitudinally into adulthood, with childhood maltreatment assessed contemporaneously (Augustyn et al., 2019; Banyard et al., 2003; Ben-David et al., 2015; Herrenkohl et al., 2013; Milaniak & Widom, 2015; Widom, Czaja, & DuMont, 2015), and provided strong and consistent support for a pattern of intergenerational transmission. For example, among a large, ethnically-diverse sample of young adult parents with and without reports of child abuse and neglect prior to the age of 12, repeated instances of neglect or multiple types of abuse experiences were associated with adult perpetration of abuse or neglect, controlling for other child and adult risk factors (Ben-David et al., 2015). Similarly, two prospective studies utilizing matched comparison samples followed from childhood into adulthood found that the combined effects of sexual abuse, physical abuse, physical neglect and/or witnessing violence predicted parents’ use of severe physical discipline, child neglecting behavior, and reports to protective services (Banyard et al., 2003; Milaniak & Widom, 2015). Adults with child maltreatment histories were 2.5–3 times more likely to perpetrate CPA than adults without such experiences, whether documented by arrest reports or self-reports of abusive behavior (Milaniak & Widom, 2015). Given the more rigorous methodology of these prospective studies, they provide strong evidence in support of the increased risk for adult perpetration of maltreatment associated with childhood victimization.

3.1.4. Fathers

More than half of the studies examining the intergenerational transmission of abuse included solely mothers in their samples, leaving open the question of whether the associations described in the previous section are consistent among fathers. Of the 22 studies that included fathers as subjects, 5 conducted analyses by gender, finding differences between the relationships for mothers and fathers (Cappell & Heiner, 1990; Ferrari, 2002; Heyman & Slep, 2002; Niu, Liu, & Wang, 2018; Simons et al., 1991) and one study examined only fathers (Ellonen et al., 2017). These six studies suggest there may be gender specificity to the processes at play in the intergenerational transmission of abuse, although it should be noted that only one of the studies (Niu et al., 2018) used a validated measure to assess retrospective childhood maltreatment experiences. Consistent with the broader literature base, several authors found a significant association between fathers’ history of physical childhood abuse and hitting their own children (Ellonen et al., 2017; Heyman & Slep, 2002; Simons et al., 1991); however, these effects were weaker for fathers than for mothers (Niu et al., 2018; Simons et al., 1991), and in one study, significant only for mothers, although this study did not use a validated scale to assess childhood maltreatment (Cappell & Heiner, 1990). While mothers exposed to both interparental and parent-child violence in childhood were more than twice as likely to engage in physical punishment compared to those exposed to only one form of violence, there was no additive effect for multiple forms of violence for fathers (Heyman & Slep, 2002). Interestingly, Ferrari (2002) found that a history of childhood abuse or neglect was associated with a lower likelihood of college-enrolled fathers using physical punishment, and a greater likelihood of using reasoning and nurturing behaviors with their children. However, the type and severity of childhood maltreatment experiences were not delineated in this study, making it difficult to evaluate these incongruous findings. Overall, given the small number of studies including fathers and the weaker methodology of these studies, additional research is needed to gain a better understanding of the patterns of intergenerational transmission among fathers.

3.1.5. Mediators

Sixteen studies examined ecological factors that may help to explain (mediate) the direct relationship between childhood victimization and adult perpetration. In one of the earliest studies to do so, Simons et al. (1991), found weak support for mediation by beliefs in physical discipline and having a hostile personality, and neither family-of-origin nor current income was associated with mothers’ or fathers’ aggressive parenting behaviors. Education, however, was inversely associated with aggressive parenting of boys (but not girls) for both mothers and fathers. Controlling for all these factors, the direct relationship between experiencing aggressive parenting in childhood and engaging in aggressive parenting in adulthood remained significant, suggesting that alternative pathways warrant investigation.

Among subsequent studies, one of the most consistent findings is the increased risk imparted by exposure to domestic violence. For example, in a complex model of child and adult familial violence among men and women living in six Asian and Pacific countries, Fulu et al. (2017) found direct and indirect pathways from witnessed abuse of one’s mother, child maltreatment, and adult IPV victimization to physical abuse of one’s child. Further, mothers’ experiences of adult IPV have consistently – and across demographically varied samples – mediated the relationship between reported past childhood maltreatment and use of physical and psychological aggression as a parent (Barrett, 2010; Frías-Armenta & McCloskey, 1998; Fulu et al., 2017; Miranda, de la Osa, Granero, & Ezpeleta, 2013; Schuetze & Eiden, 2005).

Studies of parental mental health symptoms as mediators of the relationship between childhood victimization and parental perpetration report more mixed findings than those for IPV. Dissociative symptoms and substance use disorders have each been found to mediate the transmission of maltreatment (Kim, Trickett, & Putnam, 2010; Libby et al., 2008). While adults’ depression and PTSD symptoms have been found to contribute unique variance to abusive parenting practices (e.g., Banyard et al., 2003; Libby et al., 2008; Pears & Capaldi, 2001), most tests of mediation were unsupported (Banyard et al., 2003; Libby et al., 2008; Pears & Capaldi, 2001; Zuravin & Fontanella, 1999). The only exception was a study of primarily low-income, African-American mothers by Schuetze and Eiden (2005) in which depressive symptoms were found to mediate the relationship between past CSA and use of punitive discipline. Notably, other forms of childhood victimization were not assessed, leaving the possibility that these findings could be attributable to their unmeasured influence. Relatedly, supportive relationships also did not mediate physical or sexual abuse in childhood and use of punitive discipline. (Banyard et al., 2003).

The lack of robust findings for a directly mediated pathway through mental health symptoms may suggest a more complex process involving additional unmeasured variables. Frías-Armenta and McCloskey (1998), for example, found support for a serial mediation model in which maternal history of abuse was associated with family dysfunction (marital violence and maternal & paternal alcohol use) which was in turn associated with authoritarian parenting style (including parents’ disciplinary beliefs and strategies) which was associated with verbal and physical coercive tactics and physical abuse. Two prospective studies examined the role for adolescent problem behaviors in the aftermath of childhood maltreatment. One found no relationship between adolescent delinquency or substance use and subsequent perpetration of child physical maltreatment (Capaldi et al., 2019), while the other found evidence of mediation by adolescent problem behaviors, and “precocious transitions” (i.e., school drop-out; independent living) (Augustyn et al., 2019).

3.1.6. Moderators

Twelve studies examined factors that potentially influence (moderate) the direct relationship between childhood victimization and adult perpetration. One study found that mental health symptoms moderated the risk of intergenerational transmission for parents who experienced childhood victimization, but not in the expected direction. Pears and Capaldi (2001) found that high levels of abuse in parents’ childhood coupled with high levels of depression and PTSD symptoms made it less likely that parents would abuse their children, suggesting that these symptoms may cause parents to withdraw from stressful or conflictual interactions.

Social support has been found to buffer against some of the negative sequelae of trauma (Simon, Roberts, Lewis, van Gelderen, & Bisson, 2019), but findings related to its role in the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment were mixed. Although satisfaction with friendships was associated with reduced risk, and loneliness was associated with increased risk of using severe physical discipline among low-income CSA survivors (Banyard et al., 2003), supportive relationships did not moderate the transmission of harsh physical discipline in a prospective community sample (Banyard et al., 2003; Kim, Trickett, & Putnam, 2010). In contrast, parenting stress moderated the intergenerational transmission of abuse among a large sample of middle-class Chinese parents. Associations between both mothers’ and fathers’ childhood experiences of psychological aggression and corporal punishment and their use of these strategies with their preschool aged children were stronger when parenting stress was high (Niu et al., 2018). Finally, cultural factors (familism, machismo, valuing children) did not moderate relationships between childhood abuse/neglect and physical punishment among a diverse sample of parents (Ferrari, 2002), nor did attitudes related to corporal punishment (Chung et al., 2009).

3.2. Problematic parenting

While childhood maltreatment, as demonstrated above, incurs an increased risk for abusive parenting, in fact, only a small percentage of adults who were abused as children abuse their own children (Augustyn et al., 2019; Egeland et al., 1988; Madigan et al., 2019). Thus, parents who were maltreated as children may be at greater risk of engaging in other forms of compromised parenting behaviors – including role reversal and rejecting, controlling, permissive, or intrusive behaviors. Twenty-eight articles examined the association between parental childhood abuse and these other forms of problematic parenting behaviors (See Appendix). Due to the breadth of parenting behaviors that fall into this category, the results in this section are grouped by these most commonly investigated outcomes.

3.2.1. Role reversals

Four studies of mothers and their school-aged children examined whether experiences of CSA lead to an over reliance on children to meet parents’ emotional needs, and parental emotional over-involvement with their children (Alexander, Teti, & Anderson, 2000; Burkett, 1991; Marcenko, Kemp, & Larson, 2000; Rea & Shaffer, 2016). Studies in this group tended to be relatively small (n’s range from 40 to 127) but utilized a number of demographically varied samples and methodologies, including both self-reported and observed parenting behaviors. Three of these studies suggest that mothers who report having experienced CSA may be more likely to be highly emotionally involved with their children and to rely heavily on their children to meet their emotional needs (Alexander et al., 2000; Burkett, 1991; Rea & Shaffer, 2016). However, in a study of 127 low-income, African-American mothers of school aged children, mothers with a history that included CSA reported that they engaged in less role-reversal with their children compared with mothers with a history of only CPA or no abuse history. Although inter-item correlations for the self-report measure used were low, calling into question the rigor with which the role-reversal construct was assessed, these findings suggest that the risk of role reversal may not be specific to CSA (Marcenko et al., 2000), and may be moderated by ethnicity. In addition, Alexander et al. (2000) found that emotional over-involvement may be moderated by the presence of a supportive adult intimate relationship.

3.2.2. Inconsistent discipline

In one study, mothers who were victims of incestuous and alcoholic fathers reported being less consistent with their children as compared to adult children of alcoholics with no history of incest and women with no known childhood trauma or other risk factors (Cole, Woolger, Power, & Smith, 1992); however, other forms of childhood maltreatment were not assessed in this study. In contrast, a study by Collin-Vézina et al. (2005) of mothers of children referred to child protection services evaluated a range of childhood abuse and neglect experiences and found that childhood physical and emotional abuse and neglect were associated with inconsistent discipline, but CSA was not, suggesting that there may be some specificity to the association between childhood abuse experiences and inconsistent discipline.

3.2.3. Permissive parenting

Findings from two small studies of women receiving social and/or mental health services (Jaffe, Cranston, & Shadlow, 2012; Ruscio, 2001) suggest a possible association between mothers’ reported histories of CSA and their reported permissive parenting. However, an examination of a community sample of mothers with and without a history of childhood trauma found no association between mothers’ reported CSA or other interpersonal, or noninterpersonal trauma and their reports of permissive parenting (Schwerdtfeger, Larzelere, Werner, Peters, & Oliver, 2013), and the former studies’ findings of an association did not hold when CPA, socioeconomic status, and parental alcoholism were controlled (Ruscio, 2001) or among women who were residing in a domestic violence shelter but not CPS-referred (Jaffe et al., 2012). Together, these studies suggest that previous associations between CSA and permissive parenting may, indeed, be a spurious association, as it has only been documented when other forms of maltreatment have not been accounted for, or among women with severe parenting deficits, suggesting that perhaps other factors would better explain this relationship.

3.2.4. Rejection/withdrawal

Four studies provide limited but consistent evidence that parents’ reported experiences of childhood maltreatment, especially CSA, are associated with difficulty in responding to their children’s needs. A study of 45 low-income mothers of infants found that a reported history of childhood sexual and/or physical abuse was associated with observed emotionally withdrawn caregiving behaviors (Lyons-Ruth & Block, 1996). CSA was most strongly associated with decreased maternal involvement and a flattened affect. This effect has been replicated among 318 Spanish mothers of children and adolescents referred for mental health treatment (Miranda et al., 2013) and among 150 Israeli mothers of young children (Ben Shlomo & Ben Haim, 2017). In these studies, maternal childhood abuse and neglect experiences were associated with self-reported and child-reported maternal rejection. In a rare study that included fathers, CSA was associated with a rejecting style of parenting among fathers, but not mothers (Newcomb & Locke, 2001).

3.2.5. Hostile/intrusive behaviors

In a series of studies of 105 women with childhood sexual trauma, Zvara, Meltzer-Brody, Mills-Koonce, and Cox (2017); Zvara, Mills-Koonce, Appleyard Carmody, and Cox (2015) found that women reporting past CSA exhibited more intrusive parenting behaviors during an observed interaction with their young children compared to 99 matched controls. Potential protective factors (income, education, marital stability) did not attenuate the effects, but other forms of childhood maltreatment were not assessed. However, among 45 low-income mothers and their 18-month-old children, a history of CPA but not CSA was associated with observed hostile parenting (Lyons-Ruth & Block, 1996). Further, among a community sample of 173 mothers oversampled for childhood maltreatment and their 6-month old children, no relationships emerged between reported histories of any type of child maltreatment and observed hostile parenting (Huth-Bocks, Muzik, Beeghly, Earls, & Stacks, 2014; Sexton, Davis, Menke, Raggio, & Muzik, 2017). These somewhat conflicting findings may be clarified by two studies that found that only dual CPA and CSA experiences were associated with self-reported and observed harsh discipline, suggesting that polyvictimization places parents at greatest risk of engaging in harsh or hostile parenting (Ehrensaft, Knous-Westfall, Cohen, & Chen, 2015; Pasalich, Cyr, Zheng, Mcmahon, & Spieker, 2016). However, the association between a high level of adverse childhood events and self-reported hostile parenting disappeared when adjusted for marital status, education, and ethnicity, underscoring the importance of accounting for broader environmental stressors in the examination of predictors of harsh parenting (Oosterman, Schuengel, Forrer, & De Moor, 2019). The fact that parenting was assessed via observation in all but two of these studies is a methodological strength of this body of work.

3.2.6. Authoritarian parenting

A community sample of 105 mothers of toddlers reporting histories of childhood maltreatment were more likely to report an authoritarian parenting style, characterized by greater levels of physical punishment, verbal hostility, and nonreasoning punishment, compared to mothers reporting no childhood maltreatment or only noninterpersonal trauma (Schwerdtfeger et al., 2013). In contrast, among a clinical sample of 45 mothers receiving outpatient services, reported past CSA was negatively associated with authoritarian parenting, when physical abuse and growing up in an alcoholic home were controlled (Ruscio, 2001). This latter finding may not be surprising, given the earlier findings that suggest that women reporting CSA are more likely to demonstrate withdrawn parenting behaviors, which are somewhat in contrast to an authoritarian parenting style.

3.2.7. Other problematic parenting behaviors

A number of studies have examined parents’ childhood maltreatment experiences in relation to a composite of negative parenting behavior that combines multiple types of problematic parenting. One study of 46 mothers recovering from substance use disorder found that neglect was associated with problematic parenting (behaviors associated with permissiveness, authoritarian, and overly verbose styles of parenting), but past CPA and CSA were not (Harmer, Sanderson, & Mertin, 1999). Similarly, Rodriguez and Tucker (2011) did not find an association between CPA and problematic parenting in a small study of mothers. Locke and Newcomb (2004); Newcomb and Locke (2001) found that among a larger community sample of parents, a composite childhood maltreatment history variable predicted a latent factor of poor parenting practices that included rejection, aggression, neglect and low warmth. In a clustering approach, mothers of 8–11 year old children who demonstrated mid- and high-levels of anger, hostility, psychological control, and psychological unavailability reported higher levels of childhood emotional abuse than mothers who exhibited low levels of these parenting behaviors, although CSA also may have been involved because it differentiated the high and low emotional abuse groups (McCullough, Han, Morelen, & Shaffer, 2017; McCullough, Harding, Shaffer, Han, & Bright, 2014). Finally, in a study of 246 parents of 8–11 year old children, while mothers’ family-of-origin experiences of witnessed and experienced aggression were unrelated to their parenting strategies, among fathers, family-of-origin experiences of aggression were associated with doing nothing or yelling in response to children’s misbehavior (Margolin, Gordis, Medina, & Oliver, 2003). While these studies provide limited additional support to the argument that childhood maltreatment experiences are associated with an increased risk for a broad range of problematic parenting practices, given the breadth with which both childhood abuse and problematic parenting were defined amongst these studies, it is difficult to draw any firm conclusions.

3.2.8. Mediators and moderators

Eight studies examined mediators and moderators in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and problematic parenting behaviors. While dissociative symptoms were found to mediate the association between physical and emotional abuse and neglect and inconsistent discipline (Collin-Vézina et al., 2005), neither physiological reactivity (Oosterman et al., 2019) nor polydrug use (Locke & Newcomb, 2004) mediated relationships between childhood maltreatment and problematic parenting behaviors. Two studies identified variables that moderated the effect of CSA on problematic parenting, including unsatisfactory intimate relationships (Alexander et al., 2000) and parental gender (Newcomb & Locke, 2001). Another study found that mothers who were older at childbirth were at high risk for emotionally unsupportive parenting behaviors only in the context of having high levels of sustained past emotional maltreatment and high emotion dysregulation (the latter only for mothers who were younger at childbirth) (McCullough et al., 2017). In contrast, Zvara and colleagues (Zvara et al., 2015; Zvara, Mills-Koonce, & Cox, 2017) did not find that income, education, marital stability or child sex attenuated the effect of past CSA on harsh parenting.

3.3. Positive parenting behaviors

The next two sections examine the impact of childhood maltreatment on positive behavioral and affective aspects of parenting. In this first section we review the 12 studies that examined the association between parents’ childhood maltreatment experiences and positive parenting behaviors (see Appendix). The results are grouped by the parenting outcome examined. It should be noted that the studies in this section relied exclusively on retrospectively self-reported histories of parents’ childhood maltreatment, and primarily (with three exceptions) on parental reports of their parenting behaviors, significant methodological limitations of this small body of literature.

3.3.1. Positive discipline strategies

Nine studies included parenting behaviors commonly associated with optimal outcomes for children, including the use of positive reinforcement, reasoning, and limit-setting, and the provision of clear expectations and structure (Barrett, 2009; Cohen, 1995; Collin-Vézina et al., 2005; Ferrari, 2002; Fujiwara, Okuyama, & Izumi, 2012; Kim, Trickett, & Putnam, 2010; Margolin et al., 2003; Ruscio, 2001; Seltmann & Wright, 2013). In a small group comparison study, mothers with a history of familial CSA (n = 26) scored lower on limit setting and expectations for their children’s behavior compared with mothers without a CSA history (n = 28) (T. Cohen, 1995). Seltmann and Wright (2013) found similar results among 54 maternal survivors of familial CSA; severity of abuse was associated with reported limit setting indirectly through mothers’ depressive symptoms. However, both of these studies failed to control for other forms of childhood maltreatment, potentially confounding these relationships with the influence of other forms of childhood victimization. Indeed, in a clinical sample of 45 mothers receiving outpatient therapy services, women with histories of CSA did not differ from the normative sample on their reported use of authoritative parenting practices, controlling for CPA and SES. However, women reporting both CSA involving penetration and dysfunctional parenting attitudes reported lower levels of authoritative parenting (Ruscio, 2001). Although the three abovementioned studies suggest that childhood maltreatment may interfere with mother’s use of positive discipline, their generalizability is limited as they involve small samples of primarily White and/or highly educated women. Indeed, a more methodologically rigorous study of the impact of CSA on parenting among a community sample of 483 predominantly low-income African American mothers, found that women with and without a reported history of CSA did not differ on their reported use of nonviolent discipline. Further, controlling for other forms of adversity, neither CSA nor CPA were associated with nonviolent discipline, whereas both neglect and witnessing domestic violence in childhood had inverse relationships with reported use of nonviolent discipline (Barrett, 2009).

Three studies assessing multiple types of childhood maltreatment provided mixed findings. Fujiwara et al. (2012) found that Japanese mothers residing in shelters reporting a history of CPA were less likely to report praising their children, even after controlling for domestic violence and mental health symptoms. In a study of parents of 8–11-year-old children, Margolin et al. (2003) did not find a relationship between reported family of origin aggression (CPA, or IPV between parents) and positive parenting behaviors (consistency, structure, reasoning, and a nonrestrictive attitude) for mothers or fathers. Another study found that fathers enrolled in college who reported a history of CPA and neglect were more likely to use reasoning, while no association was identified between reported childhood maltreatment history and reasoning for mothers (Ferrari, 2002).

3.3.2. Other aspects of positive parenting behaviors

Four studies examined associations between CSA and other aspects of positive parenting, including communication, monitoring, and supervision. A study of a community sample of primarily White, middle-class adolescents and their mothers (n = 913) did not find that mothers’ reported CSA experiences predicted child-reported monitoring or communication effectiveness (Testa, Hoffman, & Livingston, 2011). Similarly, among 6–11 year old CPS-referred children (n = 93), maternal reported history of CSA was not associated with reported monitoring and supervision when other forms of childhood maltreatment were controlled (Collin-Vézina et al., 2005). However, in two small studies of mothers who were survivors of incest, survivors had lower mean scores on communication compared to mothers without a history of CSA (T. Cohen, 1995), and maternal histories of CSA were linked indirectly with lower levels of communication via maternal depressive symptoms (Seltmann & Wright, 2013).

3.3.3. Emotion socialization parenting behaviors

A less frequently examined aspect of positive parenting behaviors within the childhood maltreatment literature is the behavior that parents engage in to help their children learn to identify and comprehend their own emotions as well as that of others, appropriately display and communicate their emotions, and modulate their emotional response. Three studies focused on emotion socialization parenting behaviors (Cohen, 1995; Koren-Karie, Oppenheim, & Getzler-Yosef, 2008; Rea & Shaffer, 2016). In a study of 64 mothers of school-aged children, all reported forms of childhood maltreatment (CSA, CPA, and physical and emotional abuse and neglect) were negatively associated with observations of mothers’ supportive responses to children’s negative emotions (Rea & Shaffer, 2016). Cohen (1995) found that women with a history of CSA reported lower levels of emotional communication, compared to women without a history of CSA, although no other risk factors or types of childhood maltreatment experiences were controlled in the study. Finally, in a study of 33 mothers with a history of CSA and their school-aged children, there were no bivariate associations between the severity of mothers’ CSA experiences and observations of their sensitive guidance during a discussion of emotions with their children. However, mothers’ who were more resolved regarding their traumatic past showed greater levels of sensitive guidance with their children (Koren-Karie et al., 2008).

3.3.4. Mediators

Four studies underscore the role of parental mental health symptoms in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and positive parenting behaviors. Among 93 mothers of school-aged children referred to child protection services, while there was no direct effect of any of the categories of childhood abuse or neglect on the reported use of positive reinforcement, maternal dissociation negatively predicted its use, suggesting a potential indirect effect (Collin-Vézina et al., 2005). Similarly, in a study of 54 survivors of familial CSA, severity of abuse was found to affect limit setting and communication only indirectly through mothers’ depressive symptoms (Seltmann & Wright, 2013). Results of a study by Kim, Trickett, and Putnam (2010) suggest that CSA is not directly or indirectly associated with mothers’ ability to provide positive structure for their sexually abused daughters; rather this form of parenting was indirectly predicted by reports of childhood experiences of punitive discipline, a factor representing physical punishment, verbal punishment, and guilt induction. Further, the relationship between punitive discipline and positive structure was mediated by mothers’ dissociative symptoms. Finally the relationship between mothers’ CSA experiences and their observed supportive and unsupportive responses to their children’s negative emotions were mediated by mothers’ emotional over-involvement (Rea & Shaffer, 2016).

3.4. Affective aspects of positive parenting

Twenty-three studies examined the association of parents’ childhood maltreatment histories with affective aspects of positive parenting, including parental warmth, sensitivity and emotional availability (See Appendix). Although there was variability in how these constructs are defined, often associated with the developmental age of the child, a strength of this body of literature is that the majority of parenting assessments (78%) were based on observers’ ratings during parent-child interactions. Because of the differences in how this construct is conceptualized and expressed with children at different developmental stages, the studies in this section are grouped by age.

3.4.1. Infants

Twelve of the studies examined positive affective parenting among parent-infant dyads, all but three samples exclusively with mothers (Bert, Guner, & Lanzi, 2009; Dayton, Huth-Bocks, & Busuito, 2016; Driscoll & Easterbrooks, 2007; Fuchs, Möhler, Resch, & Kaess, 2015; Huth-Bocks et al., 2014; Moehler, Biringen, & Poustka, 2007; Pereira et al., 2012; Sexton et al., 2017; Spieker, Oxford, Fleming, & Lohr, 2018; Thompson-Booth, Viding, Puetz, Mayes, & McCrory, 2019; Zajac, Raby, & Dozier, 2019; Zvara, Meltzer-Brody, et al., 2017). In a cluster analysis of adolescent mothers and their 18 month old babies, Driscoll and Easterbrooks (2007) found that mothers in the group that scored lowest on observed sensitivity were more likely to report a history of CPA than mothers in the sensitive-engaged group, while Bert et al. (2009) found that for both teen and adult first-time mothers increased reports of emotional abuse and physical abuse in childhood were associated with lower reported responsivity to their 6 month old babies, but reported CSA experiences were not associated. Looking at the changes in mother-infant interactions over time, Fuchs et al. (2015) found that mothers with reported CSA and CPA histories and matched controls did not differ in their displays of emotional availability when their infants were 5 months old. Nevertheless, only the control group mothers demonstrated a developmentally normative increase in emotional availability over time, creating a significant difference in emotional availability between these two groups of mothers at 12 months. These findings suggest that childhood abusive experiences, particularly CPA experiences, may interfere with the developing relationship between mothers and their infants. However, in other examinations of mothers and their infants, composite reports of childhood maltreatment were not associated with observed positive parenting (Huth-Bocks et al., 2014; Moehler et al., 2007; Sexton et al., 2017; Zajac et al., 2019). Potentially, given the Fuchs et al. (2015) findings, it could be that a longer follow-up period may have garnered different results.

3.4.2. Mediators

Six studies examined potential mediators of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and sensitive parenting during infancy. In a study of the influence of mothers’ experiences of interpersonal aggression (in childhood and adulthood) on their perceptions of infant emotion and observed responsive and sensitive parenting behaviors with their 6 month old infants, Dayton et al. (2016) found indirect effects such that childhood maltreatment was associated with psychological IPV, which was associated with a negative attribution bias of their infants’ emotional state. This bias was, in turn, associated with less responsive and sensitive parenting. Similarly, Thompson-Booth et al. (2019) identified an indirect association between childhood maltreatment and maternal dyadic reciprocity through mothers’ lower attentional bias to infant (versus adult) faces. Finally, three studies found support for indirect models in which maternal mental health mediated the association between childhood maltreatment and sensitive parenting (Pereira et al., 2012; Spieker et al., 2018; Zvara, Meltzer-Brody, et al., 2017). In contrast, a study of mothers, half of whom had experienced childhood maltreatment, did not find that psychological distress mediated the relationship between mothers’ abuse history and their emotional availability with their infants (Fuchs et al., 2015).

3.4.3. Early childhood

Seven studies examined positive affective parenting among mothers and their children between 3 and 6 years old (Bailey, DeOliveira, Wolfe, Evans, & Hartwick, 2012; Ben Shlomo & Ben Haim, 2017; Dilillo, Tremblay, & Peterson, 2000; Fitzgerald, Shipman, Jackson, McMahon, & Hanley, 2005; Labella, Raby, Martin, & Roisman, 2019; Zajac et al., 2019; Zvara et al., 2015). Findings in this group were quite mixed. For example, a composite of reported childhood maltreatment experiences was not associated with self-reported acceptance of children among 150 Israeli mothers of children six and under (Ben Shlomo & Ben Haim, 2017), nor with observed sensitivity among 178 CPS-referred parents (Zajac et al., 2019). However, self-reported neglect and emotional maltreatment were found to be inversely associated with observed maternal non-hostility among a small sample (n = 82) of at-risk mothers (Bailey et al., 2012). Perhaps most notable are the results of the only prospective study conducted in this area, in which childhood experiences of abuse and neglect were associated with both observed and interview-rated supportive parenting among a group of 122 parents followed from birth (Labella et al., 2019). Although direct effects disappeared when childhood demographic covariates were included in the model, indirect effects through romantic competence were robust to these covariates.

Findings were similarly mixed in the four studies that compared women with and without histories of CSA but did not control for other forms of maltreatment. Two found no differences between the groups on observed supportive parenting behaviors (Dilillo et al., 2000; Fitzgerald et al., 2005). However, in two studies by Zvara et al (Zvara et al., 2015; Zvara, Mills-Koonce, & Cox, 2017), mothers who experienced CSA were observed to exhibit less sensitive parenting. Although income, education, and marital stability did not attenuate these effects, child gender did moderate the relationship such that mothers with CSA experiences demonstrated more sensitivity toward their daughters than their sons. Given the findings reported for mothers of infants that found the most evidence for associations among CPA and composite assessments of childhood maltreatment and supportive parenting, future studies with mothers of young children that include CPA and other forms of childhood maltreatment might shed more light on these findings.

3.4.4. School age and adolescence

The final set of 7 studies included samples of children ages 6–18 years old, or studies in which the ages of the children in the home were not specified. Two studies using the same sample of predominantly African-American mothers, found that women with a history of CSA scored lower on a measure of parenting warmth than women without this history; however, when demographic characteristics and other forms of childhood adversity were included, the association was no longer significant. In contrast, perceived childhood neglect remained significant (Barrett, 2009, 2010). A longitudinal study of primarily White parents found that CSA, but not physical abuse, predicted lower levels of availability and time spent with their child (M age = 8.3). A history of both forms of childhood abuse predicted lower levels of availability, but not time spent with the child. The authors concluded that CSA may lead to emotional distance in the parent-child relationship (Ehrensaft et al., 2015). In contrast, an ethnically diverse college sample of fathers who reported a childhood history of abuse and neglect have been found to be more likely to use nurturing behaviors, although this association was not true for mothers in the study (Ferrari, 2002). Elsewhere, family of origin aggression was not related to nurturance or sensitivity among an ethnically diverse sample of middle-income parents of 8–11 year old children (Margolin et al., 2003), and a composite child maltreatment score was not associated with observed sensitivity during parent-child interactions among a sample of largely low-income, ethnic-minority, CPS-referred parents and their 8-year-old children (Zajac et al., 2019). Finally, among mothers diagnosed with depression, childhood emotional abuse was associated with lower child-reported maternal acceptance, controlling for depression and demographic risk factors. Mother-reported CPA, CSA, and neglect were not associated with acceptance (Zalewski, Cyranowski, Cheng, & Swartz, 2013).

3.4.5. Mediators

In bivariate analyses, Barrett (2010) found that adult IPV mediated the relationship between CSA and parenting warmth; however, this finding did not hold when other risk factors were entered into the model. Notably, maternal depression was significant, suggesting that this, rather than IPV, may mediate this relationship.

3.5. Additional parenting domains

While the primary focus of this review is childhood abuse’s impact on parenting behaviors, several studies also examined more internal constructs such as parenting stress and self-perception (e.g., confidence, effectiveness, satisfaction). Regarding parenting stress, the majority of the studies demonstrated some association between childhood abuse and increased stress, although the type of past childhood abuse varied, as well as whether the relationship was direct or indirect (e.g., through maternal depression)(Alexander et al., 2000; Ammerman et al., 2013; Bailey et al., 2012; Barrett, 2009; Cross et al., 2018; Douglas, 2000; Harmer et al., 1999; Mapp, 2006).

Of interest is the fact that of the 14 articles that examined parents’ self-perceptions of their own parenting, more than half focused solely on CSA, and only three of those studies controlled for other forms of childhood maltreatment (Banyard, 1997; Cole et al., 1992; Fitzgerald et al., 2005; Jaffe et al., 2012; Roberts, O’Connor, Dunn, & Golding, 2004; Schuetze & Eiden, 2005; Seltmann & Wright, 2013; Wright, Fopma-Loy, & Fischer, 2005; Zuravin & Fontanella, 1999). Four studies examined parenting satisfaction (Banyard, 1997; Banyard et al., 2003; Libby et al., 2008; Seltmann & Wright, 2013). Collectively this small body of literature suggests a weak, and likely indirect, association between childhood maltreatment experiences and parenting satisfaction. Ten articles examined self-perceived parenting competence (Bailey et al., 2012; Caldwell, Shaver, Li, & Minzenberg, 2011; Cole et al., 1992; Ehrensaft et al., 2015; Fitzgerald et al., 2005; Jaffe et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2004; Schuetze & Eiden, 2005; Wright et al., 2005; Zuravin & Fontanella, 1999). Overall, these studies’ findings suggested that past childhood maltreatment, and particularly CSA, is associated with lower parenting self-efficacy, but with a number of potentially complex and indirect pathways including the role of parental mental health. Downstream sequelae of childhood maltreatment are likely to play an important role in mediating its effects on parent self-perceptions, with mental health symptoms currently the best researched candidate.

4. Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes the research examining associations among childhood maltreatment (physical and emotional abuse and neglect, sexual abuse, and witnessing violence) and a full range of positive and negative parenting behaviors. Thus, it goes beyond evaluating the validity of putative intergenerational cycles of violence and abuse to focus on the commission and omission of aspects of parenting that have the potential to greatly affect children’s adjustment. As summarized in the Appendix, there was great variation among the studies in the way that childhood maltreatment was defined (e.g., single versus multiple victimization types) and evaluated (e.g., self-report, interview, or child protective service reports); the populations included (e.g., mothers or fathers, community or clinical populations, level of cultural and socioeconomic diversity); the parenting outcomes assessed (self-report, interview, or observed); and the research design (cross-sectional, longitudinal, or prospective).

In spite of the breadth of populations, definitions, and methodologies included in these studies, there was general consistency in findings that a history of CPA confers increased risk for engaging in abusive or neglectful parenting, either directly or indirectly. In addition, witnessing violence in the home in childhood also emerged as a consistent correlate of subsequent parental violence perpetration, with unique and multiplicative effects. This finding is consistent with, and in several ways extends, results from Savage et al.’s (2019) meta-analysis, which found a small but consistent relationship between women’s histories of childhood maltreatment victimization with their use of negative parenting behaviors with their young (ages 0–6 years old) children. By including exposure to violence in the home as a witness in childhood, the current review identified the potential role of living in a violent family in childhood as an ecological framework for intergenerational transmission of victimization. Abuse and domestic violence frequently co-occur in families, making it difficult to tease apart their separate and joint effects without careful assessment of each form of victimization separately. It also is important to determine whether the combined effect of exposure both to abuse directly and to family violence as a witness may have particularly adverse effects on parenting and the safety, health and development of the next generation, in line with evidence that polyvictimization has an especially adverse impact on children that can extend into adulthood (Charak et al., 2016; Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2009).

Additional specificity was provided by considering the effects of different types of childhood exposure to intra-familial victimization. Although evidence was found for a link between past CPA and childhood witnessing of IPV with current abusive or neglectful parenting, there was little support for an association between a history of CSA and engaging in abusive or neglectful parenting. This finding stands in contrast to that of the meta-analysis by Madigan et al. (2019), which showed a small effect size estimate for intergenerational transmission of sexual abuse. This discrepancy is likely attributable to a difference in the question being examined; whereas the Madigan et al. analysis examined whether childhood maltreatment places the next generation at risk for the same type of maltreatment, perpetrated by the parent or someone other than the parent (victim-to victim transmission), our study focused on the maltreated parent as the perpetrator of abusive or neglectful parenting (victim-to-perpetrator transmission). Madigan et al. (2019) also found evidence of a small effect for intergenerational transmission of risk of neglect, and a medium effect for intergenerational transmission of physical abuse and emotional abuse. Parenting thus may be of particular concern in conferring risk of physical abuse (and possibly also emotional abuse, which would be consistent with the present review’s finding of a link with childhood witnessing of domestic violence), but less so for the less common intergenerational transmission of sexual abuse and neglect. Rather than viewing intergenerational transmission of maltreatment as a unitary phenomenon, our results suggest that a link between childhood exposure to intra-familial violence, either directly in the form of physical abuse or as a witness to domestic violence, is of particular concern for subsequent abusive or neglectful parenting.

Additionally, the present narrative systematic review was able to examine potential indirect effects that might help to account for intergenerational transmission. In that regard, adult IPV experiences also were found to be a significant mediating pathway in the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment for mothers. IPV was not considered as a factor in prior reviews on the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment (Madigan et al., 2019; Savage et al., 2019), although those reviews did call for research identifying mediators that could account for intergenerational transmission. The well documented adverse impact of IPV on women (Sanz-Barbero, Barón, & Vives-Cases, 2019), their children (Meijer, Finkenauer, Tierolf, Lünnemann, & Steketee, 2019), and their newborn’s perinatal health (Scrafford, Grein, & Miller-Graff, 2019) is consistent with the current finding that parents’ exposure to IPV may be a link between childhood exposure to maltreatment and abusive parenting as an adult. Additional potential mediators or moderators of the effects of childhood maltreatment on subsequent parenting and the intergenerational transmission of victimization warrant future research, including race, ethnicity and culture (Wang, Henry, Smith, Huguley, & Guo, 2019), racism and associated disparities (Williams, Lawrence, & Davis, 2019), and socioeconomic status, poverty, and associated disparities (Nuru-Jeter et al., 2018).

Where Savage et al. (2019) reviewed studies only with mothers, the present review considered the potential intergenerational effects of childhood maltreatment on fathers as well. Evidence of intergenerational cycles of abuse for fathers was infrequently evaluated and methodologically weak, almost exclusively relying on retrospective assessments of childhood maltreatment utilizing unvalidated measures. Within the context of these limitations, findings tended to differ from that for mothers, underscoring the need for more inclusion of fathers in research that is methodologically rigorous. One notable finding was that fathers who reported a history of childhood abuse or neglect were, in one study, less likely to use physical punishment with their children than fathers who did not report experiencing childhood maltreatment (Ferrari, 2002). Although mothers also often break the cycle of violence, the quality of fathers’ involvement in their child’s life has been shown to be a protective factor that may mitigate the risk of the child’s developing problems in adolescence (Yoon et al., 2018), highlighting the potential importance of fathers’ resilience in the wake of their own past maltreatment. In addition, among adolescents at risk for maltreatment, higher quality of fathers’ involvement was associated with lower levels of externalizing and internalizing problems—but higher amounts of fathers’ involvement had the opposite effect when fathers were physically abusive (Yoon, Bellamy, Kim, & Yoon, 2018). Thus, it is important to investigate the impact of childhood adversity on fathers’ potential protective or adverse roles in their children’s health and development, both in relation to their positive and abusive parenting and to their potential contribution to inter-spousal conflicts that could adversely impact their child by leading to IPV. This not only underscores the importance of exploring different trajectories for mothers and fathers, but also the possibility that under some circumstances parents with abuse histories may be particularly resilient and may be able to break the intergenerational cycle of abuse in parenting their children.

The present review also disaggregated “negative” parenting behaviors such as hostile, rejecting, or emotionally overly involved parenting in order to distinguish between abusive and problematic parenting, and also included inconsistent discipline and permissiveness as categories of negative parenting behaviors. Although these compromised parenting behaviors are associated with negative outcomes for children, their association with parents’ maltreatment histories are far less frequently investigated than those with abusive or neglectful parenting, and the studies as a whole tend to be methodologically weaker. Indeed, with the exception of hostile/intrusive parenting, each specific type of problematic parenting behavior was only investigated within a small number of studies, almost exclusively utilizing retrospective reports of parents’ childhood maltreatment experiences and frequently with only one form of childhood maltreatment assessed in the study, precluding the evaluation of unique and multiplicative effects. Further, the preponderance of those studies had small sample sizes and used broad composites of negative parenting behaviors that made it difficult to draw conclusions. Nevertheless, a few preliminary patterns emerged. In studies that examined problematic parenting behaviors, mothers with histories of CSA consistently demonstrated increased role reversal, although there was a lack of support for associations with permissiveness or inconsistent discipline. Retrospectively reported childhood maltreatment also was consistently associated with parents’ emotional rejection of and withdrawal from their infants, school-aged children, and adolescents, for both mothers and fathers. Findings for hostile parenting were more mixed, with some studies suggesting that the cumulative impact of polyvictimization places parents at greatest risk for engaging in harsh or hostile parenting.