Abstract

Desbuquois dysplasia (DBQD) is a severe chondrodysplasia characterized by short stature, retarded development, multiple joint dislocations, and a distinct radiological appearance of the proximal femur. Pathogenic variants in the calcium-activated nucleotidase 1 (CANT1) or xylosyltransferase 1 (XYLT1) gene have been previously reported to cause DBQD. Here we present a 12-year-old boy manifesting the typical features of DBQD type 1 caused by a homozygous intronic variant c.836-9G>A of CANT1. To our knowledge, this is the first DBQD case described in China revealing that a CANT1 variant was also responsible for DBQD in the Chinese population and further emphasizing the role of CANT1 variants in the etiology of DBQD type 1. Our finding provides certainty for the DBQD clinical diagnosis of this patient and expands the spectrum of known DBQD genetic risk factors. On the basis of this study, amniocentesis-based prenatal diagnosis or preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD)-based assisted reproduction could be a helpful aristogenesis strategy to avoid the birth of a DBQD affected child.

Keywords: Desbuquois dysplasia, CANT1 variant, clinical diagnosis, aristogenesis

Introduction

Desbuquois dysplasia (DBQD; OMIM 251450) is a rare, autosomal recessive disease characterized by short stature and limbs, delayed growth, progressive scoliosis, and joint laxity and dislocation [1]. Other associated clinical defects include thoracic hypoplasia and peculiar facial traits such as a flat round face, a short nose, and micrognathia [2]. The major definitive radiological finding of DBQD is a “Swedish key” appearance of the proximal femur, which is caused by prominent lesser trochanter and occurs in almost all DBQD patients [3]. DBQD is clinically and radiologically heterozygous. It’s divided into two groups according to the presence (type 1) or absence (type 2) of hand deformities, which comprise an extra metacarpal ossification center distal to the second metacarpal, a delta-shaped phalanx, and dislocated phalangeal joints [4]. The newly defined subtype called “Kim variant” is characterized by a normal hand shape and no superfluous ossification center. What really distinguishes it from the other two types is the existence of advanced carpal bone age, short metacarpals, and elongated phalanges [5].

The genetic etiology of DBQD is still largely unknown, as only calcium-activated nucleotidase 1 (CANT1) and xylosyltransferase 1 (XYLT1) have been identified as causative genes. CANT1 encodes a calcium-dependent nucleotidase which belongs to the apyrase family and has a preference for UDP followed by GDP and UTP, but the role of CANT1 in skeletal formation remains undiscovered [2]. Loss of CANT1 function causes DBQD, and Huber et al. first demonstrated that CANT1 variants caused DBQD type 1 in nine families, followed closely by Faden et al. [1,3]. In 2011, Furuichi et al. proved that CANT1 variants were also responsible for DBQD type 2 and the “Kim variant” [2]. Interestingly, almost all the Japanese and Korean patients in their study carried the same variant, c.676G>A, which is thought to have a common founder variant between these two ethnic groups [6]. As for the XYLT1 gene, it functions in the process of proteoglycans synthesis and is found mainly associated with DBQD type 2 [7-10]. Over the past decade, a series of studies about DBQD have been carried out around the world [11-13]; however, no study on DBQD in China has yet been done.

Among the reported CANT1 variants, including missense, nonsense, frameshift, and the splicing site variants, most are exonic variants. Little is known about the pathogenicity of the intronic variants [14]. In this study, we first reported a Chinese boy who displayed DBQD type 1 with a homozygous intronic variant of CANT1 and emphasized the role of the intronic variant in the occurrence of DBQD.

Materials and methods

Clinical information

A male patient from a Chinese consanguineous family was enrolled in our study through a genetic counseling clinic where his parents looked for fertility guidance. Clinical and radiographic assessments were performed by medical professionals. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained for our use of the clinical information and the publication of the photographs.

Exome sequencing and analysis of CANT1 variants

Peripheral blood samples from the patient and his parents were collected. Genomic DNA was extracted using the standard protocol of the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The human CANT1 reference sequence (NM_138793) was determined through the NCBI GenBank. To screen the variants, exome sequencing was performed on the Illumina Hiseq4000 platform using XGen Exome research panel v 1.0 (Nanodigmbio, Shanghai, China). DNA reads were mapped against the human genome reference (hg19/GRCh37). Public databases including 1000 genomes (http://www.1000genomes.org/variation-pattern-finder), Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC, http://exac.broadinstitute.org), and dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/) were used to evaluate whether the variant we found was novel or not and the variant frequency among populations. The identified CANT1 variant was then verified by Sanger sequencing and the raw sequence data were analyzed using Lasergene DNA Star (Madison. WI, USA).

Results

Clinical features of the patient

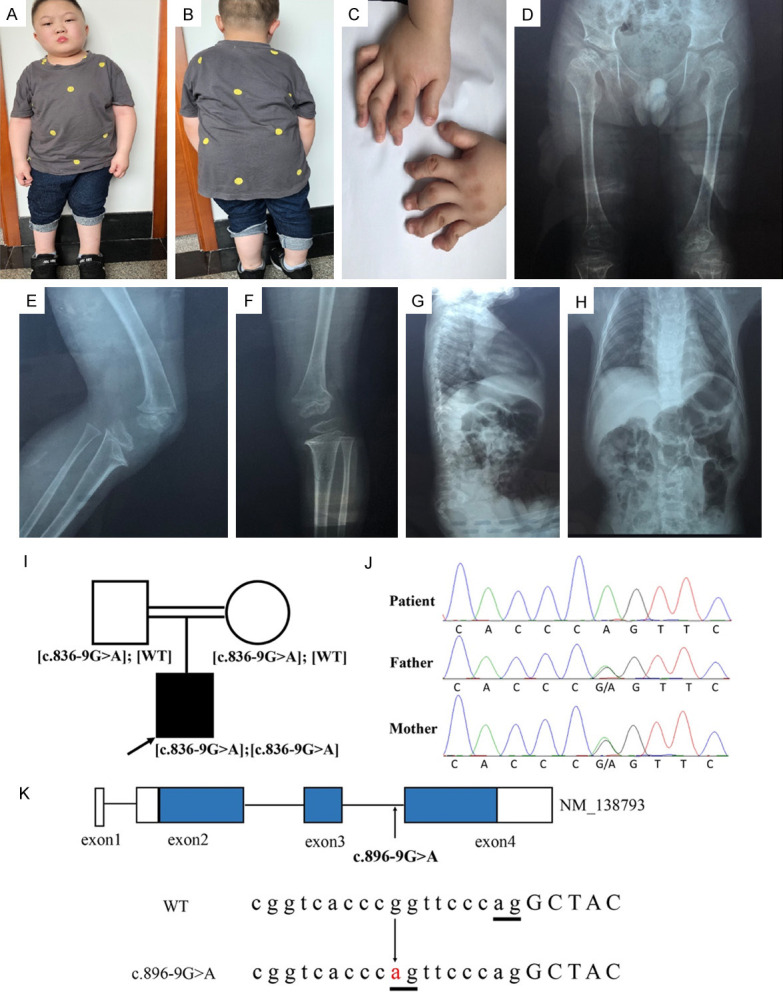

The anthropometric parameters of the 12-year-old boy included a height of 105 cm (-5.9 z score) and a weight of 40 kg. He had severe growth and development failures characterized by short stature and limbs, but his intelligence was normal. His peculiar facial appearance mainly included a round face, a flat nasal bridge, a widened eye space, and a short neck (Figure 1A, 1B). His abnormal hands had short fingers, a broad thumb, and dislocated finger joints due to the missing distal phalanges (Figure 1C). The major radiological examinations indicated a typical “Swedish key” appearance of the proximal femur (Figure 1D) and severely malformed knees with a dislocated patella above the lateral epicondyle of the femur (Figure 1E, 1F). Other malformations included scoliosis and chest dysplasia (Figure 1G, 1H). The muscle abilities of the patient were impaired such that long-distance walking, running, and jumping were impossible for him. A summary of the clinical and radiological symptoms is shown as Table 1.

Figure 1.

Clinical photographs and CANT1 variant identification. (A-C) The appearance of the patient aged 12. Short stature, special facial traits, and abnormal hands are shown. (D) Radiographs of the patient’s pelvis, the typical “Swedish key” appearance of the proximal femur is shown. (E and F). Radiographs of the patient’s knees. Lateral view of the left (E) and right knees (F) exhibit dislocated patella and joints dislocation. (G and H) represent lateral and front views of the patient’s thoracic vertebra. Thoracic abnormality (G) and scoliosis (H) are found. (I and J) Pedigree and Sanger validation of c.836-9G>A in the consanguineous family. Squares indicate male family members, circles indicate female members, a black solid circle and an arrow indicate the patient. (K) Schematic diagram of the CANT1 transcript NM_138793. The blue and blank areas represent the coding region and UTR of the exons, respectively. The arrows indicate the position of the variant. Capital and lowercase letters represent the exon and intron sequence, respectively. The underlines in bold indicate splice sites.

Table 1.

Clinical and radiological features of the Desbuquois dysplasia patient

| Items | Detailed information |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Chinese Han |

| Sex | male |

| Consanguinity | first cousin |

| Age | 12 years old |

| Intelligence | normal |

| Anthropometric measurements | 105 cm of height, 40 kg of weight |

| Facial features | round face, flat nose, wide eyes gap |

| Hands deformities | broad and short thumbs, dislocated finger joints, missing of middle phalanges |

| Joint laxity | knees |

| Thoracic spine | scoliosis |

| Hip | Swedish key appearance, |

| Other associated anomalies | hypotonia of the hands, walking and jumping difficulties, obesity |

Identification of a novel homozygous variant in CANT1

Since the DBQD locus maps to chromosome 17q25.3 [15], we analyzed the homozygous region on this interval and selected six candidate genes, including the human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 2 gene (TIMP2), c1q and tumor necrosis factor related protein 1 gene (C1QTNF1), lectin galectin 3 binding protein gene (LGALS3BP), dynein axonemal heavy chain 17 (DNAH17), ubiquitin specific peptidase 36 (USP36), and CANT1. Candidate variants were selected according to the following criteria: a) not reported or reported with a frequency lower than 0.1% in the public databases mentioned above; b) present in a homozygous state; c) predicted to be deleterious by PROVEAN (http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php), SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/), and Polyphen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/). No deleterious variants were found in the former five genes, but a novel variant, c.836-9G>A of CANT1 was identified. The Sanger validation showed that it’s homozygous in the patient and heterozygous in his parents, consistent with the autosomal recessive inheritance pattern of DBQD (Figure 1I, 1J). Frequencies of minor allele A in ExAC (3.3×10-5) and the 1000 Genomes databases (2×10-4) were lower than 0.1%, indicating that c.836-9G>A was a rare variant. The heterozygous form of c.836-9G>A was described in dbSNP (rs538543007), but there’s no pathological information or publications about the homozygous variant we found.

The variant, c.836-9G>A was located within intron 3 of the CANT1 gene (NM_138793). The transition from G to A at the indicated position would produce a new splicing site and result in a 7 bp (TTCCCAG) retention in exon 4, which generates a stop codon after 8 missense amino acids (Figure 1K).

Review of the literature on DBQD

Several CANT1 variants have been identified among all types of DBQD patients. Here we reviewed the PubMed database and summarized all the reported DBQD cases caused by CANT1 mutations in the medical literature (Table 2). Most of the known variants are located in the exons, and little was known about the contribution of the intronic variants. The identification of intronic variant c.836-9G>A in our study further emphasized the critical role of the CANT1 gene in DBQD etiology. And more importantly, it implied that intronic CANT1 variants also contributed to DBQD and expanded the spectrum of known pathogenic variants in CANT1.

Table 2.

Summary of the CANT1 variants reported in Desbuquois dysplasia cases

| Ethnicity | Consanguinity | Location | Nucleotide change† | Amino acid change | type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sri Lankan | Yes | 5’UTR+exon 1 | del2703bp (hom‡) | no | I¶ |

| Turkish | Yes | exon 3 | c.734delC (hom) | p.P245RfsX3 | I |

| Turkish/Iranian | Yes | exon 4 | c.898C>T (hom) | p.R300C | I |

| French/Saudi/Israeli | Yes | exon 4 | c.899G>A (hom) | p.R300H | I |

| Moroccan | Yes | exon 4 | c.907_911insGCGCC (hom) | p.S303AfsX20 | I |

| Brazilian | No | exon 2/4 | c.374G>A/c.896C>T (chet§) | p.W125X/p.P299 L | I |

| Saudi | Yes | exon 4 | c.893_897insGCCGC (hom) | p.325fsX | I |

| Australian | No | exon 2 | c.228_229insC/c.617T>C (chet) | p.W77LfsX13/p.L224P | I |

| Turkish | Yes | exon 2 | c.375G>C (hom) | p.W125C | II†† |

| Japanese | Yes | exon 3 | c.676G>A (hom) | p.V226M | KV‡‡ |

| Japanese | No | exon 3/4 | c.676G>A/c.861C>A (chet) | p.V226M/p.C287X | KV |

| Japanese | No | exon 2/3 | c.494T>C/c.676G>A (chet) | p.M165T/p.V226M | KV |

| Korean | No | exon 3/4 | c.676G>A/c.1079C>A (chet) | p.V226M/p.A360D | KV |

| Korean | No | intron 2/exon 3 | IVS2-9G>A/c.676G>A (chet) | p.G279VfsX8/p.V226M | KV |

| German | Yes | exon 2 | c.336C>A (hom) | p.D112E | I |

| German | No | exon 2 | c.228_229insC/c.277_278delCT (chet) | p.L93VfsX89/p.W77LfsX13 | I |

| German | No | exon 2 | c.228_229insC (hom) | p.W77LfsX13 | I |

| Moroccan | Yes | exon 4 | c.1121T>A (hom) | p.I374N | I |

| Dutch | No | exon 2 | c.100delinsTT/c.358delC (chet) | p.A34FfsX56/p.Q120KfsX10 | |

| Turkish/Yemeni | Yes | exon 2 | c.531_532del>T (hom) | p.T178LfsX4 | I |

| Bangladeshi | No | exon 2 | c.100delinsTT/c.277_278delCT (chet) | p.A34FfsX56/p.L93VfsX89 | I |

| Turkish | Yes | exon 4 | c.909C>G (hom) | p.S303R | II |

| Turkish | Yes | intron 1 | c.-342+1G>A (hom) | no | KV |

| Japanese | No | exon 3 | c.805delC (hom) | p.L269CfsX54 | I |

| Indian | Yes | exon 2 | c.467C>T (hom) | p.S156F | KV |

| Pakistani | Yes | exon 2 | c.551C>G (hom) | p.T184R | KV |

| Pakistani | Yes | exon 3 | c.643G>T (hom) | p.E215X | I |

| Chinese§§ | Yes | intron 3 | c.836-9G>A (hom) | p.G279VfsX8 | I |

number of nucleotides were referred to the first adenine of initiation codon ATG;

hom, homozygous;

chet, compound heterozygous;

I, Desbuquois dysplasia type 1;

II, Desbuquois dysplasia type 2;

KV, Kim variant;

present in our study.

Discussion

In this study, we identified a homozygous intronic variant, c.836-9G>A of CANT1 in a boy from a consanguineous family who suffered from DBQD type 1. This is the first DBQD case reported in China. In addition to the classical clinical features, including a short stature, facial dysmorphism, knee joint laxity and “Swedish key” appearance, thoracic abnormality and obesity were also noted in the patient.

DBQD should be distinguished from other skeletal conditions. Because of some similar phenotypes, DBQD may be improperly classified into other syndromes. The patient in our study was initially misdiagnosed with diastrophic dysplasia due to his growth retardation and multiple bone problems. Only after the detection of the CANT1 variant was he correctly diagnosed with DBQD. For a long time, the predominant “Swedish key” appearance and metacarpal deformity have been used as specific criteria for the DBQD clinical diagnosis. Nevertheless, the clinical and radiological heterogeneity of DBQD significantly increases the difficulty of distinguishing it from other DBQD-like diseases. Laccone et al. examined a case without these disease-associated abnormalities [16]. What’s more, prenatal ultrasound proved insufficient to classify a skeletal dysplasia disease as DBQD type 1 [17]. The rapid development of high-throughput sequencing throws light on this problem. In a recent study, utilizing the whole exome sequence allowed researchers to successfully recognize DBQD type 1 before the specific prenatal ultrasound signs occurred, demonstrating the superiority and importance of genetic detection [18]. Taking this into consideration, molecular genetic tests are great needed to support diagnostic certainty.

Previous reported CANT1 variants effected CANT1 function either by decreasing the enzyme activity or by degrading mRNA [2]. Variant c.836-9G>A was supposed to produce a new splicing site which would result in a truncated protein (p.G279fsX8). So, we speculate that c.836-9G>A may cause a partial or complete loss of the CANT1 protein function. However, further work is needed to confirm this experimentally.

The heterozygous form of c.836-9G>A variant existed with a low frequency (3.3×10-5) in the Japanese population in the ExAC database. Interestingly, heterozygous c.836-9G>A was also found in Koreans [2] and in our Chinese patient’s parents. We assumed that the carrier frequency of c.836-9G>A might be much higher in East Asians than in other ethnic groups. More DBQD patients should be tested to support this hypothesis.

In terms of clinical value, our finding could provide a new clue for prepotency. As we described before, this family intended to have a second child and looked for fertility guidance. Based on our study, PGD based assisted reproductive technology or amniocentesis-based prenatal diagnosis aimed at the c.836-9G>A locus would help avoid DBQD infants.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (17411966200).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Huber C, Oules B, Bertoli M, Chami M, Fradin M, Alanay Y, Al-Gazali LI, Ausems MG, Bitoun P, Cavalcanti DP, Krebs A, Le Merrer M, Mortier G, Shafeghati Y, Superti-Furga A, Robertson SP, Le Goff C, Muda AO, Paterlini-Brechot P, Munnich A, Cormier-Daire V. Identification of CANT1 mutations in Desbuquois dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:706–710. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuichi T, Dai J, Cho TJ, Sakazume S, Ikema M, Matsui Y, Baynam G, Nagai T, Miyake N, Matsumoto N, Ohashi H, Unger S, Superti-Furga A, Kim OH, Nishimura G, Ikegawa S. CANT1 mutation is also responsible for Desbuquois dysplasia, type 2 and Kim variant. J Med Genet. 2011;48:32–37. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.080226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faden M, Al-Zahrani F, Arafah D, Alkuraya FS. Mutation of CANT1 causes Desbuquois dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:1157–1160. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faivre L, Cormier-Daire V, Eliott AM, Field F, Munnich A, Maroteaux P, Le Merrer M, Lachman R. Desbuquois dysplasia, a reevaluation with abnormal and “normal” hands: radiographic manifestations. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;124A:48–53. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim OH, Nishimura G, Song HR, Matsui Y, Sakazume S, Yamada M, Narumi Y, Alanay Y, Unger S, Cho TJ, Park SS, Ikegawa S, Meinecke P, Superti-Furga A. A variant of Desbuquois dysplasia characterized by advanced carpal bone age, short metacarpals, and elongated phalanges: report of seven cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:875–885. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai J, Kim OH, Cho TJ, Miyake N, Song HR, Karasugi T, Sakazume S, Ikema M, Matsui Y, Nagai T, Matsumoto N, Ohashi H, Kamatani N, Nishimura G, Furuichi T, Takahashi A, Ikegawa S. A founder mutation of CANT1 common in Korean and Japanese Desbuquois dysplasia. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:398–400. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bui C, Huber C, Tuysuz B, Alanay Y, Bole-Feysot C, Leroy JG, Mortier G, Nitschke P, Munnich A, Cormier-Daire V. XYLT1 mutations in desbuquois dysplasia type 2. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:405–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamsheer A, Olech EM, Kozłowski K, Niedziela M, Sowińska-Seidler A, Obara-Moszyńska M, Latos-Bieleńska A, Karczewski M, Zemojtel T. Exome sequencing reveals two novel compound heterozygous XYLT1 mutations in a Polish patient with Desbuquois dysplasia type 2 and growth hormone deficiency. J Hum Genet. 2016;61:577–583. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silveira C, Leal GF, Cavalcanti DP. Desbuquois dysplasia type II in a patient with a homozygous mutation in XYLT1 and new unusual findings. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:13588–13595. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo L, Elcioglu NH, Iida A, Demirkol YK, Aras S, Matsumoto N, Nishimura G, Miyake N, Ikegawa S. Novel and recurrent XYLT1 mutations in two Turkish families with Desbuquois dysplasia, type 2. J Hum Genet. 2017;62:447–451. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue S, Ishii A, Shirotani G, Tsutsumi M, Ohta E, Nakamura M, Mori T, Inoue T, Nishimura G, Ogawa A, Hirose S. Case of Desbuquois dysplasia type 1: potentially lethal skeletal dysplasia. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:e26–9. doi: 10.1111/ped.12383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh A, Kim OH, Iida A, Park WY, Ikegawa S, Kapoor S. A novel CANT1 mutation in three Indian patients with Desbuquois dysplasia Kim type. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menzies L, Cullup T, Calder A, Wilson L, Faravelli F. A novel homozygous variant in CANT1 in a patient with Kim-type Desbuquois dysplasia. Clin Dysmorphol. 2019;28:219–223. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0000000000000291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nizon M, Huber C, De Leonardis F, Merrina R, Forlino A, Fradin M, Tuysuz B, Abu-Libdeh BY, Alanay Y, Albrecht B, Al-Gazali L, Basaran SY, Clayton-Smith J, Désir J, Gill H, Greally MT, Koparir E, van Maarle MC, MacKay S, Mortier G, Morton J, Sillence D, Vilain C, Young I, Zerres K, Le Merrer M, Munnich A, Le Goff C, Rossi A, Cormier-Daire V. Further delineation of CANT1 phenotypic spectrum and demonstration of its role in proteoglycan synthesis. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1261–1266. doi: 10.1002/humu.22104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faivre L, Le Merrer M, Al-Gazali LI, Ausems MG, Bitoun P, Bacq D, Maroteaux P, Munnich A, Cormier-Daire V. Homozygosity mapping of a Desbuquois dysplasia locus to chromosome 17q25.3. J Med Genet. 2003;40:282–284. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.4.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laccone F, Schoner K, Krabichler B, Kluge B, Schwerdtfeger R, Schulze B, Zschocke J, Rehder H. Desbuquois dysplasia type I and fetal hydrops due to novel mutations in the CANT1 gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:1133–1137. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baynam G, Kiraly-Borri C, Goldblatt J, Dickinson JE, Jevon GP, Overkov A. A recurrence of a hydrop lethal skeletal dysplasia showing similarity to Desbuquois dysplasia and a proposed new sign: the Upsilon sign. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:966–969. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houdayer C, Ziegler A, Boussion F, Blesson S, Bris C, Toutain A, Biquard F, Guichet A, Bonneau D, Colin E. Prenatal diagnosis of Desbuquois dysplasia type 1 by whole exome sequencing before the occurrence of specific ultrasound signs. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019:1–4. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1657084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]