Abstract

The discovery of insulin in 1921 has been one of greatest scientific achievements of the 20th century. Since then, the availability of insulin has shifted the focus of diabetes treatment from trying to keep patients alive to saving and improving the life of millions. Throughout this time, basic and clinical research has advanced our understanding of insulin synthesis and action, both in healthy and pathological conditions. Yet, multiple aspects of insulin production remain unknown. In this review, we focus on the most recent findings on insulin synthesis, highlighting their relevance in diabetes.

Graphical abstract

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00125-020-05192-7) contains a slideset of the figures for download, which is available to authorised users.

Keywords: Beta cell, Insulin biosynthesis, Insulin maturation, Post-transcriptional regulation, Proinsulin conversion, Review, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Discovered first by Frederik Banting and Charles Best in 1921, insulin is a 51-amino-acid long peptide hormone, which is key for control of glucose homeostasis, metabolism and cell growth [1]. Insulin is thought to be only produced and secreted by the beta cells of the pancreatic islets, although controversial findings have suggested that minute amounts may also be expressed in a subset of neurons in the central nervous system [2]. Within 1–10 min following a meal, hyperglycaemia prompts beta cells to secrete a small fraction (<5%) of their insulin content. Systemic circulation distributes insulin to its main target cells, namely hepatocytes, promoting their glucose storage via glycogen synthesis, and skeletal muscle cells and adipocytes, to stimulate their glucose uptake. Thereby, through these concerted actions, blood glucose is lowered to fasting levels [3].

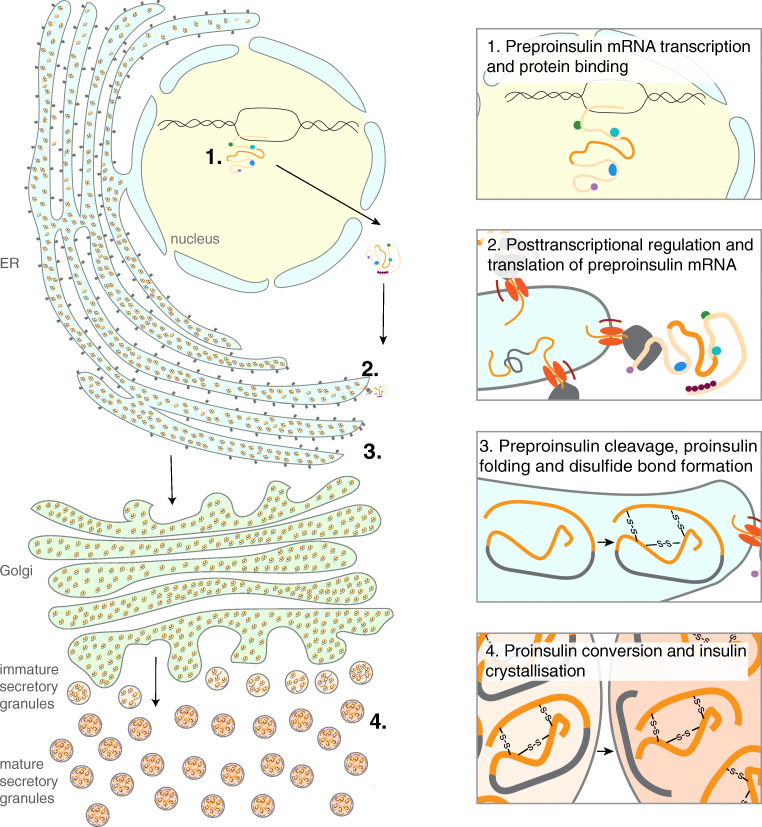

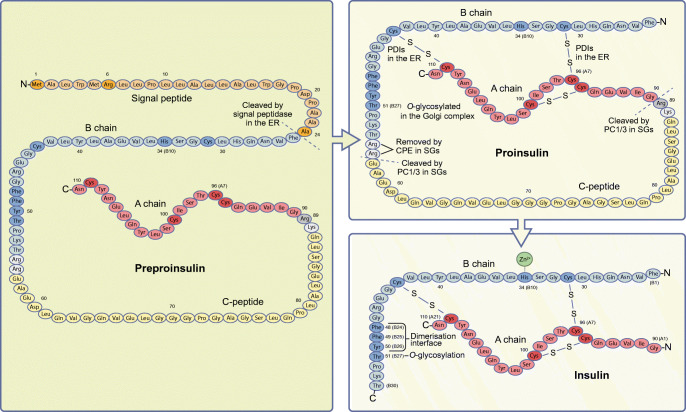

Insulin biosynthesis begins with the translation of mRNA into preproinsulin, a polypeptide of 110 amino acids with an N-terminal signal peptide, followed by the B chain, the connecting peptide (C-peptide) and the C-terminal A chain (Fig. 1). Upon translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the signal peptide is removed, thereby converting preproinsulin into proinsulin, and disulfide bridges form between the B and A chains. Following its exit from the ER, proinsulin moves through the Golgi complex to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) to be sorted into membrane-enclosed organelles termed secretory granules [4] (Fig. 2). Cleavage of the C-peptide in this compartment converts proinsulin into mature insulin, which consists of the B and A chains only (Fig. 1). Mature insulin is stored within secretory granules until they fuse with the plasma membrane to release insulin, or are degraded intracellularly through autophagy or direct delivery to lysosomes, otherwise defined as crinophagy [5–7].

Fig. 1.

The insulin peptide. Insulin is synthesised as a 110 amino-acid-long preproinsulin including a signal peptide (orange), a B chain (blue), a connecting peptide (C-peptide, yellow) and an A chain (red). The signal peptide targets the preproinsulin to the ER, where it is cleaved by the signal peptidase and converted into proinsulin. In the ER, three disulfide bonds are formed between cysteine residues with the help of PDIs. Proinsulin is trafficked from the ER, through the Golgi and the trans-Golgi network to secretory granules (SGs), where PC1/3 and CPE process the dibasic residues (grey) to form mature insulin. Zn2+ non-covalently binds to the HisB10 to form the insulin hexamer. Amino acids mentioned in the text are shown in a darker colour. This figure is available as part of a downloadable slideset

Fig. 2.

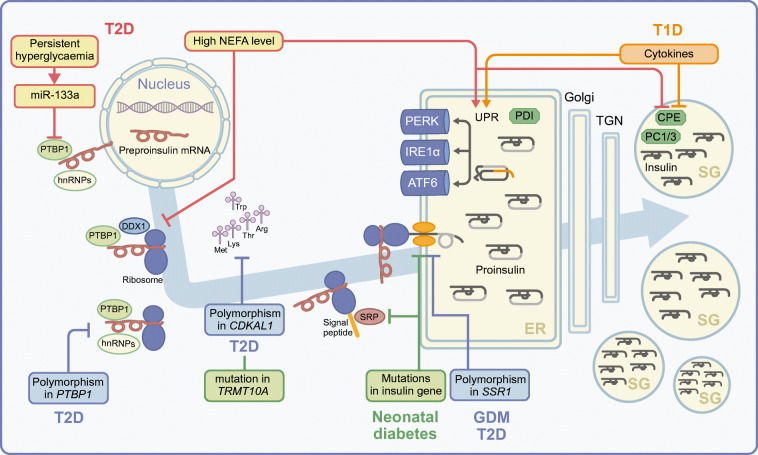

Schematic of insulin production and secretion, from mRNA to the mature hormone. The preproinsulin mRNA is stabilised by its binding to various hnRNPs in the cytosol. Preproinsulin translation and its translocation to the ER starts after the formation and activation of the ribosomal complex. Following proinsulin folding in the ER and the removal of the C-peptide, mature insulin is formed in secretory granules (SGs). Environmental changes, such as metabolic stress or inflammation, that can hamper this highly regulated process are shown in red for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and in orange for type 1 diabetes (T1D); genetic changes resulting in different types of diabetes are labelled in blue (T2D and gestational diabetes mellitus [GDM]) and in green (neonatal diabetes). ATF6, activating transcription factor 6; miR, microRNA; SRP, signal recognition particle; TGN, trans-Golgi network. This figure is available as part of a downloadable slideset

As newly-synthesised insulin is preferentially secreted [8–10], hyperglycaemia simultaneously enhances de novo insulin biosynthesis in order for beta cells to replenish their insulin granule stores and, thus, retain their secretory competence. Given the astonishing assembly rate of >3 × 103 new insulin molecules per second per beta cell [11], each step for insulin production must have been optimised during evolution.

Glucose regulates insulin mRNA transcription and translation

Glucose is the key factor controlling insulin mRNA expression. Indeed, in glucose-stimulated beta cells, insulin levels are increased 20-fold [12, 13]. This effect is mediated both by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Glucose stimulates the activity of insulin transcription factors pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX-1), neurogenic differentiation 1 (NEUROD1)–E47 and MafA at multiple levels, including changes in their expression levels, subcellular localisation, DNA-binding activity, transactivation capability and interactions with other proteins. For more information on this topic, we refer readers to another review within this special issue [14]. However, for the specific purpose of this article, it is critical to emphasise that the levels of preproinsulin (i.e. unspliced) pre-mRNA and mature (i.e. spliced) preproinsulin mRNA only increase 1 h and several hours after glucose stimulation, respectively [15]. On the other hand, insulin protein levels are already increased 30 min after exposure of rodent and human islets to hyperglycaemia [13, 16, 17]. Taken together, these data indicate that post-transcriptional mechanisms account mostly, if not entirely, for the sudden increase in insulin biosynthesis elicited by glucose stimulation.

Preproinsulin mRNA is the most abundant transcript in beta cells, accounting for ∼30% of their total mRNA content [18]. Resting beta cells store translationally repressed pre-existing copies of preproinsulin mRNA in the cytosol. Hyperglycaemia stimulates the conversion of preproinsulin mRNA into a translationally active form, by altering the combinatorial binding of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) to cis-regulatory elements in its untranslated regions (UTRs). In this way, beta cells can bypass the time-consuming transcriptional step and quickly activate insulin biosynthesis to replenish their stores [19]. In particular, as briefly summarised below, RBPs modulate preproinsulin mRNA stability [16, 18], translation initiation rates [17, 20, 21], including cap-independent translation [22, 23], and transfer to the ER [24].

Regulation of preproinsulin mRNA stability in health and diabetes

Preproinsulin mRNA has a long half-life, which is mainly regulated by a conserved polypyrimidine tract and a UUGAA-motif in its 3′-UTR [13, 16]. Glucose stimulation increases preproinsulin mRNA stability two- to threefold, as compared with non-stimulated beta cells. The best known RBP that regulates preproinsulin mRNA stability is polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 (PTBP1, also known as heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein [hnRNP] I) [25, 26]. PTBP1 binds to the 3′-UTR of preproinsulin mRNA and prevents its destabilisation by opposing T cell-restricted intracellular antigen 1-related (TIAR) protein [27]. Although it is unclear how, it is known that hyperglycaemia promotes the nucleocytoplasmic translocation and recruitment of PTBP1 to preproinsulin mRNA in the cytosol [28]. Preproinsulin mRNA stability is also enhanced by glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), which is released from nutrient-stimulated L cells in the gut. Exposure of beta cells to GLP-1 induces the protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation of the nuclear import signal within PTBP1 and, thus, its nucleocytoplasmic translocation [29], conceivably to prime beta cells for the increased insulin demand following a meal.

Other preproinsulin RBPs, at least in insulinoma cells, include hnRNP K [25, 27], hnRNP C, hnRNP E [25], hnRNP L, hnRNP U, HuD [30], and the poly(rC)-binding proteins (PCBP) 1, 2 and 3 [27]. Their involvement in preproinsulin mRNA stability remains unknown and, for some, such as hnRNP K, there are conflicting findings [30]. Yet, several of them are among the most rapidly regulated proteins in INS-1 cells exposed to hyperglycaemia or 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) [31], which, like GLP-1, enhances cAMP levels. Hence, evidence increasingly points to RBPs as being critical for rapid post-transcriptional regulation of preproinsulin mRNA.

Since the levels of preproinsulin mRNA in the islets of individuals with normoglycaemia or type 2 diabetes do not significantly differ, its stability is unlikely to be affected in type 2 diabetes [32, 33]. On the other hand, in mouse islets and insulinoma (MIN6) cells exposed to proinflammatory cytokines, no-go and nonsense-mediated RNA decay pathways are upregulated, lowering the levels of preproinsulin mRNA [34]. It is, therefore, possible that inflammation in pancreatic islets in type 1 diabetes alters preproinsulin mRNA stability, while its alternative splicing seems unaffected [35].

Regulation of preproinsulin mRNA translation in health and diabetes

While a blood glucose concentration of >4–5 mmol/l enhances insulin secretion, glucose concentrations as low as 2–4 mmol/l already support the biosynthesis of insulin to ensure maintenance of its stores [36, 37]. In mammalian cells, translation starts with the binding of various initiation factors to the 5′-UTR of mature mRNAs. This binding occurs in a prescribed order and promotes the recruitment of the small and large ribosomal subunits. Beta cells store preproinsulin mRNA in assembled polysomes. Upon glucose stimulation these polysomes are transported to the ER and preproinsulin mRNA translation starts immediately [24]. Besides common regulators of translation, such as those related to the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, several other specific factors regulate insulin translation in response to nutrients. Among them is the ATP-dependent RNA helicase DEAD-box helicase 1 (DDX1), which binds to eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF)3a and eIF4b, and to preproinsulin mRNA [38]. These findings could be relevant for the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, which is commonly associated with hyperlipidaemia; saturated NEFAs, like palmitate, acutely enhance the secretion of insulin but, unlike its other secretagogues (glucose and GLP-1), they do not concomitantly increase its production [39]. In mice, in particular, palmitate-induced phosphorylation of DDX1 displaces it from the preproinsulin mRNA and suppresses insulin biosynthesis, hence providing a direct link between hyperlipidaemia and insulin deficiency [38]. Moreover, depletion of Ca2+ levels in the ER upon exposure to palmitate can impair proinsulin folding and cause ER stress, hence further downscaling insulin biosynthesis [40].

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) deliver amino acids to translating ribosomes, and their post-transcriptional methylation enhances the fidelity and, thus, efficiency of translation. Polymorphisms or mutations in tRNA methyltransferases, such as in CDKAL1 and TRMT10A [41–43], are associated with glucose intolerance due to impaired insulin synthesis and, in the case of TRMT10A, cause a monogenetic form of young-onset diabetes associated with microencephaly and intellectual disability. Interestingly, the use of an alternative start codon in human preproinsulin mRNA can lead to the translation of a nonconventional insulin product and the generation of neoantigenic peptides thereof, which are targets of T cell-mediated autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes [44].

All eukaryotic mRNAs are capped at their 5′-UTR and translated in a cap-dependent fashion. However, cap-independent translation can occur if initiation factors are recruited closer to the first AUG codon through an internal ribosome entry site (IRES). Bypassing many of the controls for cap-dependent translation, cap-independent translation allows for protein synthesis in conditions in which the former is compromised, for example, upon irradiation, hypoxia, apoptosis or amino-acid starvation. Notably, mRNAs for insulin and other secretory granule cargoes can be translated in a cap-independent manner, thus enabling their continuous production, even in stress conditions [23] or upon inhibition of the mTOR pathway [45]. Key to this process is PTBP1, the binding of which to the preproinsulin mRNA 5′-UTR is increased upon transient hyperglycaemia. However, exposure of human islets to prolonged hyperglycaemia suppresses PTBP1 expression and insulin biosynthesis, possibly due to the concomitant upregulation of microRNA (miR)-133a, which binds to the 3′-UTR of PTBP1 mRNA [46]. Increased nuclear retention of PTBP1 in the islets of individuals with type 2 diabetes may also contribute to impaired glucose-stimulated insulin biosynthesis [47]. Furthermore, common polymorphisms within PTBP1 influence glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [48], albeit, in general, PTBP1 mRNA levels in the islets of individuals with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes are unaffected as compared with individuals with normoglycaemia [33].

Although most mutations in insulin’s amino acid sequence impair its folding in the ER [49–51] (see below), there are also single-point mutations (such as the three shown in dark orange in Fig. 1) or extensive exon deletions that affect its efficient translation (Fig. 1). In all these instances, translation initiation of preproinsulin is immediately arrested, leading to permanent neonatal diabetes. For instance, mutations in the start codon of preproinsulin cause immediate arrest of translation initiation. Downstream mutations in the signal peptide of preproinsulin, such as R6C replacement [52], also impair ER translocation and target preproinsulin for proteasomal degradation. Furthermore, mutations affecting signal-peptide cleavage, such as the A24D replacement, also cause permanent neonatal diabetes by blocking ER exit of the protein and leading to ER stress [50, 51]. Finally, polymorphisms in the gene encoding translocon-associated protein subunit α (SSR1) may alter preproinsulin translocation and, thus, predispose carriers to type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes [53, 54].

Regulation of proinsulin folding in health and diabetes

Proinsulin folding in the ER involves the establishment of three disulfide bonds, two interchain between the B and A chains and one intrachain within the A chain (Fig. 1). Altered cysteine pairing, such as upon mutations of C96 in the A chain, causes misfolding, accumulation and toxic aggregation of proinsulin in the ER leading to permanent neonatal diabetes or mature-onset diabetes of the young (reviewed previously [50]). Recent studies in a human-derived induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) model of neonatal diabetes with a C96R mutation, and in the Akita mouse model of diabetes, in which one Ins2 allele carries a C96Y replacement, suggest that proinsulin misfolding reduces beta cell proliferation and mass due to downregulation of mTOR signalling during pancreas development [55–57], rather than beta cell apoptosis, as it is commonly assumed.

In vitro studies suggest that among the 15–20 protein disulfide isomerases (PDIs) found in the human genome, PDIA1 primarily facilitates the oxidative folding of proinsulin disulfide bonds in conjunction with the oxidoreductases ER oxidoreductin 1α/β (ERO1α/β) [51, 58, 59]. In turn, ERO1α/β regenerate PDIs for subsequent rounds of disulfide bond generation. Increasing evidence suggests that modest amounts of proinsulin disulfide mispairing occurs even in healthy beta cells and that accumulation of misfolded proinsulin intermediates occurs early in type 2 diabetes [60, 61]. Thus, maintenance of a proper redox status, which relies on the continuous supply of reducing equivalents by the cytosolic thioredoxin system, is critical for proper beta cell function. Interestingly, the thioredoxin interacting protein (TXNIP), which inhibits the antioxidative action of thioredoxin and is elevated upon ER stress and insulin misfolding [62, 63], was also found to be elevated in type 2 diabetes islets [64].

Perturbance of proinsulin folding is countered by the unfolded protein response (UPR). Among the three UPR sensors, namely inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), IRE1α and PERK have been more extensively implicated in the regulation of proinsulin folding. IRE1α signalling is constitutively active under physiological conditions for control of oxidative proinsulin folding [58], whereas the PERK pathway is induced upon ER stress [65, 66]. Mutations in PERK (also known as EIF2AK3) cause the Wolcott–Rallison syndrome, an autosomal recessive permanent neonatal diabetes [65]. On the other hand, inactivating mutations of the heat shock protein p58IPK, resulting in increased PERK activity, can also cause diabetes [51, 65]. In type 1 diabetes, cytokine-induced ER stress may account for impaired folding of insulin and altered HLA presentation of antigenic peptides thereof, hence contributing to beta cell dysfunction and T cell-mediated destruction [67–69].

Regulation of proinsulin conversion into mature insulin in health and diabetes

The conversion of proinsulin into mature insulin occurs in two consecutive steps; first, the C-peptide junctions at the B and A chains are cleaved at basic residues R55–R56 and K88–R89 (Fig. 1) [70, 71]. In human beta cells, proprotein convertase 1/3 (PC1/3) is mainly responsible for C-peptide release, while in rodent beta cells, its paralogue proprotein convertase 2 (PC2) also participates in this process [72]. Next, the exopeptidase carboxypeptidase E/H (CPE) removes the dibasic residues R55–R56 at the C-terminal end of the B chain (Fig. 1) [70, 71]. Although impaired proinsulin conversion with elevated proinsulin secretion is a hallmark of type 2 [73] and type 1 diabetes [74, 75], genetic variants affecting the junction between the C-peptide and the A chain, such as replacement of R89 [50] (Fig. 1), or the proteolytic activities of either PC1/3 [76] or CPE [77] have only been identified in a few individuals with type 2 diabetes or altered glucose metabolism. While islets of donors with type 2 diabetes do not display reduced expression of PC1/3 (also known as PCSK1) and/or CPE mRNA [33, 78], one study found that palmitate treatment of islets isolated from non-diabetic deceased organ donors reduced CPE protein levels [79]. This intriguing observation remains to be validated in studies of CPE expression in islets of individuals with type 2 diabetes in situ. On the other hand, proteomic analysis indicated that PC1/3 and CPE are reduced in islets from donors with type 1 diabetes that were obtained by laser capture microdissection (LCM) [80, 81]. Besides reduced expression of PC1/3 and CPE, other mechanisms could account for the inefficient conversion of proinsulin into mature insulin. The activation of PC1/3 and CPE, which also travel through the secretory pathway together with proinsulin, is induced by the lowering of luminal pH to <6.0 and the rise of Ca2+ concentration in immature insulin secretory granules. Therefore, reduced proinsulin-to-insulin conversion may also reflect changes in luminal acidification, for instance, due to premature ageing of secretory granules, since the pH of older granules is ≥6.2 (M. Neukam and M. Solimena, unpublished results). Beta cell degranulation, due to excessive insulin demand, may also force the immediate release of immature secretory granules without providing enough time for efficient proinsulin-to-insulin conversion. This scenario, however, remains to be proven.

In most mammalian beta cells, including humans, mature insulin is stored in secretory granules as a hexamer of three dimers, each of which coordinates the binding of a Zn2+ molecule to H34 (B10) in the B chain (Fig. 1). Albeit, a notable exception to this is guinea pig insulin, which does not bind to Zn2+. Import of Zn2+ into secretory granules is mediated by the zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8; encoded by the SLC30A8), a known autoantigen of type 1 diabetes and a risk gene for type 2 diabetes. Depletion of Zn2+ impairs both insulin crystallisation, thereby altering the characteristic appearance of the granule-dense core that can be seen using electron microscopy, and insulin secretion in mice [82]. Remarkably, carriers of the ZnT8 variant R325W, which correlates with lower expression of the transporter, convert proinsulin to insulin more efficiently and have a lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes. On the other hand, in these individuals, the import of Zn2+ into secretory granules may be compensated by other zinc transporters [83, 84].

The dimerisation interface of the insulin B chain, which contains the aromatic triplet F48, F49 and Y50 (Fig. 1), facilitates the sorting and maturation of proinsulin and the interaction of insulin with its receptor [49, 85–87]. Intriguingly, large-scale analysis of human and mouse islets by targeted mass spectrometry have only very recently revealed that the adjacent T51 is O-glycosylated (Fig. 1) [88]. The functional implications of this modification, however, remain to be determined.

Conclusion and some outstanding questions

As we briefly summarised above, in recent years our understanding of post-transcriptional and translational mechanisms for insulin production and their impairment in diabetes has progressed relentlessly. Still, numerous aspects of these processes remain unclear. For instance, factors involved in the regulation of splicing and nucleocytoplasmic transport of preproinsulin mRNA are unknown. Also unknown is where exactly in the cytosol resting beta cells store untranslated preproinsulin mRNA, while our knowledge about the machinery regulating its stability and degradation is rudimental. In vitro studies and animal models suggest that ER stress and proinsulin traffic are relevant to the pathogenesis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, but conclusive evidence in humans is still missing. We also lack a clear explanation for the inefficient processing and elevated release of proinsulin in type 2 diabetes. The same post-transcriptional and translational mechanisms likely coordinate the biosynthesis of other insulin granule cargoes and enable the proper assembly of these organelles [3, 26]. As exemplified by the occurrence of diabetes in carriers of mutations affecting insulin production, any deficit along this supply chain can deplete beta cells of new insulin granule stores, thereby hampering their competence for glucose-stimulated secretion. Insulin and other insulin granule cargoes are also major targets of autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes. The inherent reasons for deficient insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes and for autoimmunity against insulin granule components are, however, yet to be discovered. Thus, despite popular belief suggesting that by now we know how cells manufacture insulin [89], almost a century after the discovery of insulin, much remains to be uncovered regarding its production and release for the control of glucose homeostasis. We are nonetheless confident that ingenuity and access to ever new powerful methodologies will enable this knowledge gap to be filled.

Electronic supplementary material

(PPTX 647 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all lab members of our group for their discussions and to K. Pfriem (PLID, Dresden, Germany) for administrative assistance. We apologise to the authors whose work we could not cite due to space constraints.

Authors’ relationships and activities

The authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Abbreviations

- CPE

Carboxypeptidase E/H

- DDX1

DEAD-box helicase 1

- eIF

Eukaryotic initiation factor

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- ERO1α/β

Endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin 1α/β

- GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide 1

- hnRNP

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- IRE1α

Inositol-requiring enzyme 1α

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- PC1/3

Proprotein convertase 1/3

- PDI

Protein disulfide isomerase

- PERK

Protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

- PTBP1

Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1

- RBP

RNA-binding protein

- tRNA

Transfer RNA

- UPR

Unfolded protein response

- UTR

Untranslated region

Contribution statement

JV, JMT, K-PK and MS performed the literature search, drafted and edited the manuscript and critically revised it for important intellectual content. JV and K-PK created the figures. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. Research in the Solimena lab is supported by: the BMBF-funded German Centre for Diabetes Research (DZD e.V.); grants from the French National Agency for Research (ANR) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) (no. SO 818/6-1) and the German-Israeli Foundation (no. I-1429-201.2/2017); and the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreements no. 115881 (RHAPSODY) and no. 115797 (INNODIA), which include financial contributions from the European Union’s Framework Programme Horizon 2020, EFPIA and the Swiss State Secretariat for Education‚ Research and Innovation (SERI) under contract number 16.0097, as well as JDRF International and The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Weiss M, Steiner DF, Philipson LH, et al. Insulin biosynthesis, secretion, structure, and structure-activity relationships. In: Feingold K, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet] South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Csajbók ÉA, Tamás G. Cerebral cortex: a target and source of insulin? Diabetologia 2016 598. 2016;59(8):1609–1615. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3996-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suckale J, Solimena M. The insulin secretory granule as a signaling hub. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(10):599–609. doi: 10.1016/J.TEM.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arvan P, Halban PA. Sorting ourselves out: seeking consensus on trafficking in the beta-cell. Traffic. 2004;5(1):53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee Y, Kim J, Park K, Lee M-S. β-Cell autophagy: mechanism and role in β-cell dysfunction. Mol Metab. 2019;27:S92–S103. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller A, Neukam M, Ivanova A, et al. A global approach for quantitative super resolution and electron microscopy on cryo and epoxy sections using self-labeling protein tags. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00033-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goginashvili A, Zhang Z, Erbs E, et al. Insulin secretory granules control autophagy in pancreatic β cells. Science. 2015;347(6224):878–882. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodes CJ, Halban PA. Newly synthesized proinsulin/insulin and stored insulin are released from pancreatic B cells predominantly via a regulated, rather than a constitutive, pathway. J Cell Biol. 1987;105(1):145–153. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanova A, Kalaidzidis Y, Dirkx R, et al. Age-dependent labeling and imaging of insulin secretory granules. Diabetes. 2013;62(11):3687–3696. doi: 10.2337/db12-1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szabat M, Page MM, Panzhinskiy E, et al. Reduced insulin production relieves endoplasmic reticulum stress and induces β cell proliferation. Cell Metab. 2016;23(1):179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuit FC, Kiekens R, Pipeleers DG. Measuring the balance between insulin synthesis and insulin release. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;178(3):1182–1187. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(91)91017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guest PC, Bailyes EM, Rutherford NG, Hutton JC. Insulin secretory granule biogenesis: co-ordinate regulation of the biosynthesis of the majority of constituent proteins. Biochem J. 1991;274(Pt 1):73–78. doi: 10.1042/bj2740073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wicksteed, Barton, Herbert TP, et al. Cooperativity between the preproinsulin mRNA untranslated regions is necessary for glucose-stimulated translation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(25):22553–22558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jennings RE, Scharfmann R, Staels W (2020) Transcription factors that shape the mammalian pancreas. Diabetologia. 10.1007/s00125-020-05161-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Evans-Molina C, Garmey JC, Ketchum R, Brayman KL, Deng S, Mirmira RG. Glucose regulation of insulin gene transcription and pre-mRNA processing in human islets. Diabetes. 2007;56(3):827–835. doi: 10.2337/db06-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welsh M, Nielsen DA, MacKrell AJ, Steiner DF. Control of insulin gene expression in pancreatic beta-cells and in an insulin-producing cell line, RIN-5F cells. II. Regulation of insulin mRNA stability. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(25):13590–13594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itoh N, Okamoto H. Translational control of proinsulin synthesis by glucose. Nature. 1980;283(5742):100–102. doi: 10.1038/283100a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tillmar L, Carlsson C, Welsh N. Control of insulin mRNA stability in rat pancreatic islets: regulatory role of a 3′-untranslated region pyrimidine-rich sequence. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(2):1099–1106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammonds P, Schofield PN, Ashcroft SJH, Sutton R, Gray DWR. Regulation and specificity of glucose-stimulated insulin gene expression in human islets of Langerhans. FEBS Lett. 1987;223(1):131–137. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welsh M, Scherberg N, Gilmore R, Steiner DF. Translational control of insulin biosynthesis. Evidence for regulation of elongation, initiation and signal-recognition-particle-mediated translational arrest by glucose. Biochem J. 1986;235(2):459–467. doi: 10.1042/bj2350459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahr H, Schröder D, Ziegler B, Ziegler M, Zühlke H. Transcriptional and translational control of glucose-stimulated (pro)insulin biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1980;110(2):499–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fred RG, Sandberg M, Pelletier J, Welsh N. The human insulin mRNA is partly translated via a cap- and eIF4A-independent mechanism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412(4):693–698. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knoch KP, Nath-Sain S, Petzold A, et al. PTBP1 is required for glucose-stimulated cap-independent translation of insulin granule proteins and Coxsackieviruses in beta cells. Mol Metab. 2014;3(5):518–530. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenman IC, Gomez E, Moore CEJ, Herbert TP. The selective recruitment of mRNA to the ER and an increase in initiation are important for glucose-stimulated proinsulin synthesis in pancreatic β-cells. Biochem J. 2005;391(2):291–300. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fred RG, Welsh N. The importance of RNA binding proteins in preproinsulin mRNA stability. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;297(1–2):28–33. doi: 10.1016/J.MCE.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magro MG, Solimena M. Regulation of β-cell function by RNA-binding proteins. Mol Metab. 2013;2(4):348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fred RG, Mehrabi S, Adams CM, Welsh N. PTB and TIAR binding to insulin mRNA 3′- and 5′UTRs; implications for insulin biosynthesis and messenger stability. Heliyon. 2016;2(9):1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2016.e00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knoch KP, Bergetr H, Borgonovo B, et al. Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein promotes insulin secretory granule biogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(3):207–214. doi: 10.1038/ncb1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knoch KP, Meisterfeld R, Kersting S, et al. cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of PTB1 promotes the expression of insulin secretory granule proteins in β cells. Cell Metab. 2006;3(2):123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee EK, Kim W, Tominaga K, et al. RNA-binding protein HuD controls insulin translation. Mol Cell. 2012;45(6):826–835. doi: 10.1016/J.MOLCEL.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Süss C, Czupalla C, Winter C, et al. Rapid changes of mRNA-binding protein levels following glucose and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine stimulation of insulinoma INS-1 cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8(3):393–408. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800157-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taneera J, Prasad RB, Dhaiban S, et al. Silencing of the FTO gene inhibits insulin secretion: an in vitro study using GRINCH cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;472(6):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solimena M, Schulte AM, Marselli L, et al. Systems biology of the IMIDIA biobank from organ donors and pancreatectomised patients defines a novel transcriptomic signature of islets from individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2018;61(3):641–657. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4500-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghiasi SM, Krogh N, Tyrberg B, Mandrup-Poulsen T. The no-go and nonsense-mediated RNA decay pathways are regulated by inflammatory cytokines in insulin-producing cells and human islets and determine B-cell insulin biosynthesis and survival. Diabetes. 2018;67(10):2019–2037. doi: 10.2337/db18-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eizirik DL, Sammeth M, Bouckenooghe T, et al. The human pancreatic islet transcriptome: expression of candidate genes for type 1 diabetes and the impact of pro-inflammatory cytokines. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(3):e1002552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halban PA, Wollheim CB. Intracellular degradation of insulin stores by rat pancreatic islets in vitro. An alternative pathway for homeostasis of pancreatic insulin content. J Biol Chem. 1980;255(13):6003–6006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boland BB, Rhodes CJ, Grimsby JS. The dynamic plasticity of insulin production in β-cells. Mol Metab. 2017;6(9):958–973. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Z, Zhou M, Cai Z, et al. RNA-binding protein DDX1 is responsible for fatty acid-mediated repression of insulin translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(22):12052–12066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bollheimer LC, Skelly RH, Chester MW, McGarry JD, Rhodes CJ. Chronic exposure to free fatty acid reduces pancreatic β cell insulin content by increasing basal insulin secretion that is not compensated for by a corresponding increase in proinsulin biosynthesis translation. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(5):1094–1101. doi: 10.1172/JCI420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cunha DA, Hekerman P, Ladrière L, et al. Initiation and execution of lipotoxic ER stress in pancreatic β-cells. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 14):2308–2318. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Ouweland JMW, Lemkes HHPJ, Ruitenbeek W, et al. Mutation in mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) gene in a large pedigree with maternally transmitted type II diabetes mellitus and deafness. Nat Genet. 1992;1(5):368–371. doi: 10.1038/ng0892-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinthorsdottir V, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, et al. A variant in CDKAL1 influences insulin response and risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39(6):770–775. doi: 10.1038/ng2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Igoillo-Esteve M, Genin A, Lambert N, et al. tRNA methyltransferase homolog gene TRMT10A mutation in young onset diabetes and primary microcephaly in humans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(10):e1003888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kracht M, van Lummel M, Nikolic T, et al. Autoimmunity against a defective ribosomal insulin gene product in type 1 diabetes. Nat Med. 2017;23(4):501–507. doi: 10.1038/nm.4289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krautz C, Wolk S, Steffen A, et al. Effects of immunosuppression on alpha and beta cell renewal in transplanted mouse islets. Diabetologia. 2013;56(7):1596–1604. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2895-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fred RG, Bang-Berthelsen CH, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Grunnet LG, Welsh N. High glucose suppresses human islet insulin biosynthesis by inducing miR-133a leading to decreased polypyrimidine tract binding protein-expression. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehehalt F, Knoch K-P, Erdmann K, et al. Impaired insulin turnover in islets from type 2 diabetic patients. Islets. 2010;2(1):30–36. doi: 10.4161/isl.2.1.10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heni M, Ketterer C, Wagner R, et al. Polymorphism rs11085226 in the gene encoding polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 negatively affects glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steiner DF, Tager HS, Chan SJ, Nanjo K, Sanke T, Rubenstein AH. Lessons learned from molecular biology of insulin-gene mutations. Diabetes Care. 1990;13(6):600–609. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.6.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Støy J, Steiner DF, Park SY, Ye H, Philipson LH, Bell GI. Clinical and molecular genetics of neonatal diabetes due to mutations in the insulin gene. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010;11(3):205–215. doi: 10.1007/s11154-010-9151-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu M, Weiss MA, Arunagiri A, et al. Biosynthesis, structure, and folding of the insulin precursor protein. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:28–50. doi: 10.1111/dom.13378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo H, Xiong Y, Witkowski P, et al. Inefficient translocation of preproinsulin contributes to pancreatic β cell failure and late-onset diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(23):16290–16302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.562355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium, Asian Genetic Epidemiology Network Type 2 Diabetes (AGEN-T2D) Consortium, South Asian Type 2 Diabetes (SAT2D) Consortium, Mexican American Type 2 Diabetes (MAT2D) Consortium, Type 2 Diabetes Genetic Exploration by Next-generation sequencing in multi-Ethnic Samples (T2D-GENES) Consortium Genome-wide trans-ancestry meta-analysis provides insight into the genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2014;46(3):234–244. doi: 10.1038/ng.2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kasuga Y, Hata K, Tajima A, et al. Association of common polymorphisms with gestational diabetes mellitus in Japanese women: a case-control study. Endocr J. 2017;64(4):463–475. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ16-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Modi H, Johnson JD. Folding mutations suppress early beta-cell proliferation. eLIFe. 2018;7:e43475. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Balboa D, Saarimäki-Vire J, Borshagovski D, et al. Insulin mutations impair beta-cell development in a patient-derived iPSC model of neonatal diabetes. eLIFe. 2018;7:e38519. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Riahi Y, Israeli T, Yeroslaviz R, et al. Inhibition of mTORC1 by ER stress impairs neonatal β-cell expansion and predisposes to diabetes in the Akita mouse. eLIFe. 2018;7(3):57–63. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsuchiya Y, Saito M, Kadokura H, et al. IRE1–XBP1 pathway regulates oxidative proinsulin folding in pancreatic β cells. J Cell Biol. 2018;217(4):1287–1301. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201707143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jang I, Pottekat A, Poothong J, et al. PDIA1/P4HB is required for efficient proinsulin maturation and ß cell health in response to diet induced obesity. eLIFe. 2019;8:e44528. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44528.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haataja L, Manickam N, Soliman A, Tsai B, Liu M, Arvan P. Disulfide mispairing during proinsulin folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Diabetes. 2016;65(4):1050–1060. doi: 10.2337/db15-1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arunagiri A, Haataja L, Pottekat A, et al. Proinsulin misfolding is an early event in the progression to type 2 diabetes. eLIFe. 2019;8:e44532. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44532.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oslowski CM, Hara T, O’Sullivan-Murphy B, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein mediates ER stress-induced β cell death through initiation of the inflammasome. Cell Metab. 2012;16(2):265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yuan Q, Tang W, Zhang X, et al. Proinsulin atypical maturation and disposal induces extensive defects in mouse Ins2+/Akita β-cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chau GC, Im DU, Kang TM, et al. mTOR controls ChREBP transcriptional activity and pancreatic β cell survival under diabetic stress. J Cell Biol. 2017;216(7):2091–2105. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201701085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cnop M, Toivonen S, Igoillo-Esteve M, Salpea P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and eIF2α phosphorylation: the Achilles heel of pancreatic β cells. Mol Metab. 2017;6(9):1024–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sowers CR, Wang R, Bourne RA, et al. The protein kinase PERK/EIF2AK3 regulates proinsulin processing not via protein synthesis but by controlling endoplasmic reticulum chaperones. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(14):5134–5149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.813790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marroqui L, Dos Santos RS, Op de beeck A, et al. Interferon-α mediates human beta cell HLA class I overexpression, endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis, three hallmarks of early human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2017;60(4):656–667. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gonzalez-Duque S, Azoury ME, Colli ML, et al. Conventional and neo-antigenic peptides presented by β cells are targeted by circulating naïve CD8+ T cells in type 1 diabetic and healthy donors. Cell Metab. 2018;28(6):946–960. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verhagen J, Yusuf N, Smith EL, et al. Proinsulin peptide promotes autoimmune diabetes in a novel HLA-DR3-DQ2-transgenic murine model of spontaneous disease. Diabetologia. 2019;62(12):2252–2261. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-04994-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steiner DF, Docherty K, Carroll R. Golgi/granule processing of peptide hormone and neuropeptide precursors: a minireview. J Cell Biochem. 1984;24(2):121–130. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240240204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen Y-C, Taylor AJ, Verchere CB. Islet prohormone processing in health and disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:64–76. doi: 10.1111/dom.13401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ramzy A, Asadi A, Kieffer TJ (2020) Revisiting proinsulin processing: evidence that human β-cells process proinsulin with prohormone convertase (PC) 1/3 but not PC2. Diabetes. 10.2337/db19-0276 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Ward WK, LaCava EC, Paquette TL, Beard JC, Wallum BJ, Porte D. Disproportionate elevation of immunoreactive proinsulin in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus and in experimental insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 1987;30(9):698–702. doi: 10.1007/BF00296991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Truyen I, De Pauw P, Jørgensen PN, et al. Proinsulin levels and the proinsulin:C-peptide ratio complement autoantibody measurement for predicting type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2005;48(11):2322–2329. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1959-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wasserfall C, Nick HS, Campbell-Thompson M, et al. Persistence of pancreatic insulin mRNA expression and proinsulin protein in type 1 diabetes pancreata. Cell Metab. 2017;26(3):568–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jackson RS, Creemers JWM, Ohagi S, et al. Obesity and impaired prohormone processing associated with mutations in the human prohormone convertase 1 gene. Nat Genet. 1997;16(3):303–306. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen H, Jawahar S, Qian Y, et al. Missense polymorphism in the human carboxypeptidase E gene alters enzymatic activity. Hum Mutat. 2001;18(2):120–131. doi: 10.1002/humu.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Taneera J, Fadista J, Ahlqvist E, et al. Identification of novel genes for glucose metabolism based upon expression pattern in human islets and effect on insulin secretion and glycemia. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(7):1945–1955. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jeffrey KD, Alejandro EU, Luciani DS, et al. Carboxypeptidase E mediates palmitate-induced β-cell ER stress and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(24):8452–8457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711232105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sims EK, Syed F, Nyalwidhe J, et al. Abnormalities in proinsulin processing in individuals with longstanding T1D. Transl Res. 2019;213:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sims EK, Bahnson HT, Nyalwidhe J, et al. Proinsulin secretion is a persistent feature of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:258–264. doi: 10.2337/dc17-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wijesekara N, Dai FF, Hardy AB, et al. Beta cell-specific Znt8 deletion in mice causes marked defects in insulin processing, crystallisation and secretion. Diabetologia. 2010;53(8):1656–1668. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1733-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rutter GA, Chimienti F. SLC30A8 mutations in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;58(1):31–36. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dwivedi OP, Lehtovirta M, Hastoy B, et al. Loss of ZnT8 function protects against diabetes by enhanced insulin secretion. Nat Genet. 2019;51(11):1596–1606. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0513-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weiss MA, Lawrence MC. A thing of beauty: structure and function of insulin’s “aromatic triplet.”. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:51–63. doi: 10.1111/dom.13402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nakagawa SH, Tager HS. Role of the phenylalanine B25 side chain in directing insulin interaction with its receptor. Steric and conformational effects. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(16):7332–7341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dodson G, Steiner D. The role of assembly in insulin’s biosynthesis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8(2):189–194. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(98)80037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yu Q, Canales A, Glover MS, et al. Targeted mass spectrometry approach enabled discovery of O-glycosylated insulin and related signaling peptides in mouse and human pancreatic islets. Anal Chem. 2017;89(17):9184–9191. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bryson B. A short history of nearly everything. New York: Random House; 2003. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PPTX 647 kb)