Abstract

Genetic polymorphisms of 19 microsatellites were investigated in nine local chicken breeds collected from low, middle and high altitudes areas in China (total number was 256) and their population genetic diversity and population structure were analyzed. All breeds were assigned into three groups, including the high (Tibetan chicken (T) and Grey chicken (G), their altitudes were above 1000 m); middle (Chengkou mountainous chicken (CK), Jiuyuan chicken (JY) and Pengxian yellow chicken (PY), their altitudes were between 500 and 1000 m), and low groups (Da ninghe chicken (DH), Tassel first chicken (TF), Gushi chicken (GS) and Wenchang chicken (WC), their altitudes were below 500 m). We found 780 genotypes and 324 alleles via the 19 microsatellites primers, and the results showed that the mean number of alleles (Na) was 17.05; the average polymorphism information content (PIC) was 0.767; the mean expected heterozygosity (He) was 0.662; as for observed heterozygosity (Ho), it was 0.647. The AMOVA results indicated the genetic variation mainly existed within individuals among populations (80%). There was no genetic variation among the three altitude groups (0%). The mean inbreeding coefficient among individuals within population (FIS) was 0.031 and the mean gene flow (Nm) was 1.790. The mean inbreeding coefficient among populations within a group (FST) was 0.157. All loci deviated Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The genetic distance ranged from 0.090 to 0.704. Generally, genetic variations were mainly made up of the variations among populations and within individuals. There were rich gene diversities in the populations for the detected loci. Meanwhile, frequent genes exchange existed among the populations. This can lead to extinction of the peripheral species, such as the Tibetan chicken breed.

Keywords: altitude, chicken, genetic variation, microsatellite, population structure

Introduction

Chicken riches human civilization and promotes social development. China is one of the countries having the richest chicken genetic resources in the world, but has low resource utilization. Evaluating germplasm resources of excellent properties and making unique conservation strategies for each population, will cater for the future needs not only for China, but also for the whole world.

Studies indicated that the level of genetic variation within populations decreased with the environment altitudinal gradients increased (Premoli, 1997). However, there are also reports showed opposite results (Wen and Hsiao, 2001; Gämperle and Schneller, 2003), genetic variation wasn't affected by altitude at all (Saenz-Romero and Tapia-Olivares, 2003). Thus, more investigations for the relationship between the altitude and genetic diversities are needed.

Meanwhile, local breeds in China are facing the blow of increasing gene exchange resulted by the convenient transportation. It's important to strengthen the protection of genetic resources by detecting their genetic diversity to provide applicable preserve strategies. Microsatellites were used in diversity studies due to their dominant, highly polymorphic nature and availability throughout the genome. They are reliable markers for genetic diversity evaluation in both wild and domestic animal populations (Tadano et al., 2007). Studies have carried out via microsatellite scanning to study genetic diversity of different chicken breeds (Wimmers et al., 2000). In the current study, we collected nine chicken breeds originally raised in Southwest China and located at the high (>1000 m), middle (500–1000 m) and low (<500 m) altitudes farms to make clear whether the genetic structures of the chicken breeds were affected by the farm altitude and whether there is gene flow among these native breeds.

Materials and Methods

Populations

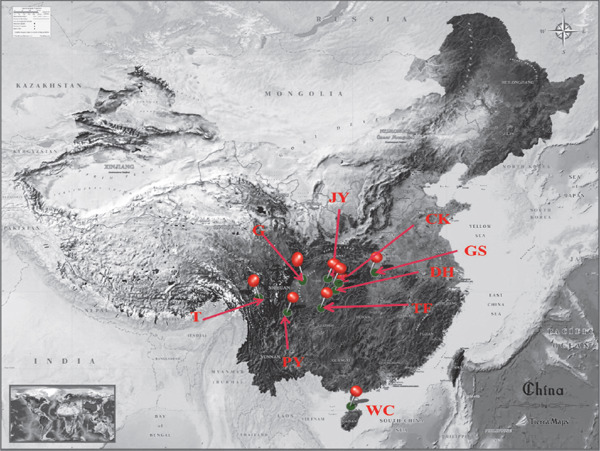

Nine populations, Tibetan chicken (T), Grey chicken (G), Chengkou mountainous chicken (CK), Jiuyuan chicken (JY), Pengxian yellow chicken (PY), Da ninghe chicken (DH), Tassel first chicken (TF), Gushi chicken (GS), and Wenchang chicken (WC) were sampled from their original environments in China (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Based on the altitudes of their farms, they were grouped into three categories, the high (breeds T and G, their altitudes were above 1000 m); middle (breeds CK, JY and PY, their altitudes were between 500 and 1000 m), and low (breeds DH, TF, GS and WC, their altitudes were below 500 m).

Fig. 1.

The locations of nine chicken populations.

Table 1. Nine chicken populations were surveyed in this study.

| Breeds | Abbreviation | Location | Sample size | Altitude1 | Group | Latitude1 | Longitude1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tibetan chicken | T | Ganzi, Sichuan | 30 | 2930 m | High | 28° 55′ 52.25′ | 99° 47′ 54.30′ |

| Grey chicken | G | Guangyuan, Sichuan | 30 | 1374 m | High | 32° 38′ 52.48′ | 106° 05′ 46.36′ |

| Chengkou mountainous chicken | CK | Chengkou, Chongqing | 27 | 753 m | Middle | 31° 56′ 51.92′ | 108° 39′ 50.76′ |

| Jiuyuan chicken | JY | Taiping town, Sichuan | 30 | 668 m | Middle | 32° 04′ 01.40′ | 108° 02′ 13.92′ |

| Pengxian yellow chicken | PY | Guihua town, Sichuan | 30 | 643 m | Middle | 31° 02′ 02.94′ | 103° 47′ 37.07′ |

| Da ninghe chicken | DH | Wuxi, Chongqing | 24 | 219 m | Low | 31° 23′ 55.57′ | 109° 34′ 11.76′ |

| Tassel first chicken | TF | Wulong, Chongqing | 30 | 177 m | Low | 29° 19′ 32.72′ | 107° 45′ 35.48′ |

| Gushi chicken | GS | Gushi, Henan | 26 | 54 m | Low | 32° 11′ 22.25′ | 115° 40′ 18.79′ |

| Wenchang chicken | WC | Wenchang, Hainan | 29 | 17 m | Low | 19° 44′ 27.63′ | 110° 46′ 21.40′ |

Original locations of the breeds. The determination of altitude, latitude and longitude using the sampling points as the criterion.

DNA Extraction

A total of 256 whole bloods were collected from wing veins and stored at −20°C. We extracted genomic DNA from whole blood using the standard phenol/chloroform method (Davoren et al., 2007). The DNA concentrations were quantified by Spectrophotometer (Eppendorf Company, Germany) and samples were diluted to a final concentration of 100 ng/µL.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Microsatellite Genotyping

Nineteen microsatellite (MS) markers were referred to the procedures of Molecular Genetic characterization of Animal Genetic Resources (International Society for Animal Genetics–Food and Agriculture Organization, ISAG–FAO, 2011), as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Detail of Microsatellite markers with fluorescence labeling at the end of 5′ fragment of forward primers.

| Locus | Chromosome | Forward primer (5′-3′) |

Reverse primer (5′-3′) |

Tm (°C) | Size range (bp) | Fluorescence labeling at the end of 5′-fragment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEI0166 | 3 | CTCCTGCCCTTAGCTACGCA | TATCCCCTGGCTGGGAGTTT | 57.5 | 354–370 | HEX |

| MCW0014 | 6 | TATTGGCTCTAGGAACTGTC | GAAATGAAGGTAAGACTAGC | 57.7 | 164–182 | FAM |

| MCW0069 | E60C04W23 | GCACTCGAGAAAACTTCCTGCG | ATTGCTTCAGCAAGCATGGGAGGA | 59 | 158–176 | FAM |

| MCW0103 | 3 | AACTGCGTTGAGAGTGAATGC | TTTCCTAACTGGATGCTTCTG | 61 | 266–270 | HEX |

| MCW0037 | 3 | ACCGGTGCCATCAATTACCTATTA | GAAAGCTCACATGACACTGCGAAA | 63.4 | 154–160 | FAM |

| MCW0330 | 17 | TGGACCTCATCAGTCTGACAG | AATGTTCTCATAGAGTTCCTGC | 61 | 256–300 | HEX |

| LEI0094 | 4 | GATCTCACCAGTATGAGCTGC | TCTCACACTGTAACACAGTGC | 57.7 | 247–287 | HEX |

| MCW0216 | 13 | GGGTTTTACAGGATGGGACG | AGTTTCACTCCCAGGGCTCG | 59 | 139–149 | FAM |

| LEI0234 | 2 | ATGCATCAGATTGGTATTCAA | CGTGGCTGTGAACAAATATG | 59 | 216–364 | HEX |

| MCW0078 | 5 | CCACACGGAGAGGAGAAGGTCT | TAGCATATGAGTGTACTGAGCTTC | 57.7 | 135–147 | FAM |

| MCW0206 | 2 | CTTGACAGTGATGCATTAAATG | ACATCTAGAATTGACTGTTCAC | 57 | 221–249 | HEX |

| ADL0112 | 10 | GGCTTAAGCTGACCCATTAT | ATCTCAAATGTAATGCGTGC | 57.7 | 120–134 | FAM |

| LEI0192 | 6 | TGCCAGAGCTTCAGTCTGT | GTCATTACTGTTATGTTTATTGC | 57.7 | 244–370 | HEX |

| ALD0268 | 1 | CTCCACCCCTCTCAGAACTA | CAACTTCCCATCTACCTACT | 61 | 102–116 | FAM |

| MCW0222 | 3 | GCAGTTACATTGAAATGATTCC | TTCTCAAAACACCTAGAAGAC | 61 | 220–226 | HEX |

| MCW0034 | 2 | TGCACGCACTTACATACTTAGAA | TGTCCTTCCAATTACATTCATGGG | 57.7 | 212–246 | HEX |

| MCW0111 | 1 | GCTCCATGTGAAGTGGTTTA | ATGTCCACTTGTCAATGATG | 61 | 96–120 | FAM |

| MCW0067 | 10 | GCACTACTGTGTGCTGCAGTTT | GAGATGTAGTTGCCACATTCCGAC | 63.4 | 176–186 | HEX |

| MCW0295 | 4 | ATCACTACAGAACACCCTCTC | TATGTATGCACGCAGATATCC | 64 | 88–106 | FAM |

Tm, annealing temperature.

PCR with two fluorescence labeling primers pairs were carried out with a total volume of 12.5 µL (Beijing Tianwei Biology Technique Corporation, Beijing, China), which containing ddH2O 4.75 µL, mix 6.25 µL, DNA 0.5 µL, and 0.5 µL of each primer (10 pmol/µL). Nine primers pairs were labeled fluorescence FAM, and the others were labeled fluorescence HEX (Table 2). The reaction steps were as following: an initial step of 5 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 40 s at 94°C, Tm (annealing temperature) for 30 s, then 30 s at 72°C and ended with a full extension cycle at 72°C for 5 min.

ABI 3730 xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used for the capillary electrophoresis of the PCR product with the following volume: HI-DI 8 µL, ROX 500 0.3 µL, and the product of PCR 0.5 µL. The estimation of allele size was determined with Gene marker Software (Soft Genetics, USA). The allele data was subjected to further genetic analysis.

Data Analysis

Genetic information of nine chicken breeds was assessed by calculating the total number of alleles (Na), gene diversity (Dg), number of genotype (Ng), the main allele frequency (MAF), observed (Ho) and expected (He) heterozygosities. Polymorphism information content (PIC) was analyzed by PowerMarker V3.25. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and effective alleles (Ne) was calculated using the GenALEx version 6.4. Molecular variance (AMOVA) was performed to estimate the hierarchical structure of genetic diversity using the program GenALEx (version 6.4). The pair-wise comparisons between populations and regions, the FST-values and the estimated pairwise Nm were also using the program GenALEx version 6.4 (Peakall and Smouse, 2012). Multilocus pairwise FST was quantified by ARLEQUIN software, version 3.1 (Schneider et al., 2000; Cortellini et al., 2011). To further analyze the Nei's standard genetic distance analysis (DA, Nei et al., 1983) among populations, we used the program PowerMarker V3.25 and MEGA5.1.

Results

Genetic Diversity of Chicken Breeds

The microsatellite polymorphism, evaluated by the Na per locus, Dg, Ng, MAF, Ho, He and PIC for each breed were summarized in Table 3. A total of 324 alleles identified via the 19 microsatellite primers distributed in 256 individuals from 9 populations. All the microsatellite loci were polymorphic. The number of alleles per locus ranged from 7 (for primers MCW0222) to 54 (for primers LEI0234) (Table 3), with a mean of 17.05; the average PIC was 0.767, which ranged from 0.470 to 0.928. The mean He was 0.662, which ranged from 0.489 (for primers MCW0103) to 0.848 (for primers LEI0234). For Ho, its mean value was 0.647, and ranged from 0.461 to 0.816; the average main allele frequency was 0.320 (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the 19 microsatellite loci across nine chicken breeds.

| Marker | MAF | Ng | Na | Dg | Ho | He | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEI0166 | 0.428 | 21 | 9 | 0.684 | 0.648 | 0.640 | 0.631 |

| MCW0014 | 0.252 | 45 | 18 | 0.843 | 0.531 | 0.653 | 0.825 |

| MCW0069 | 0.193 | 57 | 20 | 0.883 | 0.816 | 0.766 | 0.873 |

| MCW0103 | 0.525 | 10 | 8 | 0.560 | 0.461 | 0.489 | 0.470 |

| MCW0037 | 0.350 | 14 | 8 | 0.726 | 0.582 | 0.644 | 0.679 |

| MCW0330 | 0.281 | 38 | 16 | 0.842 | 0.691 | 0.718 | 0.825 |

| LEI0094 | 0.201 | 84 | 29 | 0.909 | 0.746 | 0.784 | 0.902 |

| MCW0216 | 0.279 | 20 | 10 | 0.802 | 0.547 | 0.540 | 0.774 |

| LEI0234 | 0.193 | 135 | 54 | 0.931 | 0.688 | 0.848 | 0.928 |

| MCW0078 | 0.398 | 18 | 10 | 0.755 | 0.461 | 0.531 | 0.723 |

| MCW0206 | 0.389 | 28 | 11 | 0.777 | 0.508 | 0.530 | 0.752 |

| ADL0112 | 0.346 | 20 | 11 | 0.769 | 0.711 | 0.565 | 0.735 |

| LEI0192 | 0.332 | 79 | 40 | 0.857 | 0.582 | 0.714 | 0.849 |

| ADL0268 | 0.412 | 18 | 9 | 0.710 | 0.758 | 0.675 | 0.662 |

| MCW0222 | 0.383 | 20 | 7 | 0.717 | 0.606 | 0.652 | 0.671 |

| MCW0034 | 0.252 | 83 | 27 | 0.890 | 0.738 | 0.769 | 0.883 |

| MCW0111 | 0.270 | 29 | 14 | 0.822 | 0.785 | 0.651 | 0.799 |

| MCW0067 | 0.236 | 26 | 11 | 0.841 | 0.766 | 0.671 | 0.822 |

| MCW0295 | 0.361 | 35 | 12 | 0.801 | 0.664 | 0.735 | 0.780 |

| Mean±SD | 0.320±0.091 | 41.05±32.68 | 17.05±12.43 | 0.796±0.091 | 0.647±0.111 | 0.662±0.098 | 0.767±0.112 |

MAF, main allele frequency; Ng, number of genotype; Na, number of alleles per locus; Dg, gene diversity; Ho, observed heterozygosity; He, expected heterozygosity; PIC, polymorphism information content. SD, standard deviation.

Diversity parameters in nine breeds from low, middle and high groups were shown in Table 4. The mean Na in each breed ranged from 4.79 (breed PY) to 7.05 (breed DH). The DH breed had the highest diversity, with the highest Dg (0.70), He (0.70), Ne (3.95), Na (7.05), Ng (10.84) and PIC (0.67), respectively. Breed TF had the highest MAF (0.49), and breed CK had the highest Ho. PY breed had the lowest Ho (0.57), PIC (0.58), Dg (0.63), He (0.63), Ne (2.95), Na(4.79) and Ng (8.05).

Table 4. Diversity parameters in nine chicken breeds.

| Parameters | High group |

Middle group |

Low group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | G | CK | JY | PY | DH | TF | GS | WC | |

| MAF | 0.49±0.15 | 0.44±0.13 | 0.44±0.13 | 0.41±0.12 | 0.49±0.13 | 0.43±0.14 | 0.49±0.16 | 0.47±0.16 | 0.49±0.1 |

| Ng | 9.11±4.56 | 9.84±5.80 | 9.68±4.96 | 9.84±5.10 | 8.05±2.92 | 10.84±4.19 | 9.95±5.62 | 9.90±5.08 | 8.95±5.3 |

| Na | 5.58±2.39 | 6.53±4.25 | 6.63±4.04 | 6.42±3.60 | 4.79±1.55 | 7.05±3.44 | 6.42±4.11 | 6.95±3.95 | 5.74±2.8 |

| Ne | 3.21±0.34 | 3.68±0.47 | 3.59±0.35 | 3.79±0.44 | 2.95±0.40 | 3.95±0.40 | 3.49±0.40 | 3.63±0.50 | 3.23±0.3 |

| Dg | 0.63±0.14 | 0.67±0.12 | 0.68±0.12 | 0.69±0.11 | 0.63±0.11 | 0.70±0.12 | 0.64±0.15 | 0.66±0.13 | 0.64±0.1 |

| Ho | 0.61±0.19 | 0.68±0.18 | 0.71±0.18 | 0.71±0.17 | 0.57±0.14 | 0.64±0.20 | 0.58±0.17 | 0.65±0.16 | 0.68±0.2 |

| He | 0.63±0.03 | 0.67±0.03 | 0.68±0.03 | 0.69±0.03 | 0.63±0.02 | 0.70±0.03 | 0.64±0.03 | 0.66±0.03 | 0.64±0.0 |

| PIC | 0.58±0.15 | 0.62±0.14 | 0.63±0.13 | 0.63±0.13 | 0.58±0.12 | 0.67±0.13 | 0.60±0.16 | 0.62±0.14 | 0.59±0.1 |

| FIS | 0.03±0.13 | 0.05±0.23 | −0.03±0.22 | −0.02±0.18 | 0.10±0.23 | 0.13±0.21 | 0.12±0.22 | 0.03±0.18 | −0.06±0.3 |

MAF, major allele frequency; Ng, number of genotype; Na, number of alleles; Ne, number of effective alleles; Dg, gene diversity; Ho, observed heterozygosity; He, expected heterozygosity; PIC, polymorphism information content; FIS, Between individuals within population inbreeding coefficient

Population Structure

Partitioning of genetic variability by analysis of molecular variance indicated that 80% of the total genetic variation was distributed within individual among populations, within regions relative to the total (0%) and among populations within regions (16%), with the remaining split within populations relative to the total (3%, Table 5).

Table 5. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) based on microsatellites.

| Source of variation | df | Variance components | %Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Among regions | 2 | 0.000 | 0 |

| Among pops | 6 | 1.255 | 16 |

| Among Individuals | 247 | 4.000 | 3 |

| Within Individual | 256 | 6.148 | 80 |

| Total | 511 | 7.731 | 100 |

df, degrees of freedom; %Total, percentage of the total variance.

The mean observed heterozygosity (Ho) was lower than the mean expected heterozygosity (He), which leaded in positive overall heterozygote deficiency (FIS) and inbreeding coefficient (FIT) (Table 6). However, the levels of inbreeding within individual populations and among all individuals were not significant, as indicated by jackknifed FIS and FIT estimates (0.031 and 0.184, respectively; Table 6). The FIS values varied greatly across loci, which ranged from −0.216 to 0.199. The gene flow ranged from 0.565 to 4.772 with a mean of 1.790 (Table 6).

Table 6. F statistics for 19polymorphic loci across nine chicken breeds.

| Locus | FIS | FIT | FST | Nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEI0166 | −0.008 | 0.060 | 0.068 | 3.433 |

| MCW0014 | 0.193 | 0.364 | 0.212 | 0.932 |

| MCW0069 | −0.068 | 0.067 | 0.127 | 1.724 |

| MCW0103 | 0.078 | 0.185 | 0.116 | 1.896 |

| MCW0037 | 0.101 | 0.193 | 0.103 | 2.180 |

| MCW0330 | 0.060 | 0.187 | 0.135 | 1.605 |

| LEI0094 | 0.059 | 0.178 | 0.127 | 1.718 |

| MCW0216 | 0.005 | 0.310 | 0.307 | 0.565 |

| LEI0234 | 0.188 | 0.259 | 0.087 | 2.616 |

| MCW0078 | 0.160 | 0.387 | 0.270 | 0.675 |

| MCW0206 | 0.069 | 0.344 | 0.296 | 0.596 |

| ADL0112 | −0.216 | 0.085 | 0.247 | 0.761 |

| LEI0192 | 0.199 | 0.320 | 0.151 | 1.403 |

| ADL0268 | −0.130 | −0.074 | 0.050 | 4.772 |

| MCW0222 | 0.082 | 0.166 | 0.092 | 2.482 |

| MCW0034 | 0.044 | 0.167 | 0.128 | 1.704 |

| MCW0111 | −0.185 | 0.049 | 0.198 | 1.013 |

| MCW0067 | −0.127 | 0.083 | 0.186 | 1.095 |

| MCW0295 | 0.083 | 0.158 | 0.081 | 2.838 |

| Mean±SD | 0.031±0.13 | 0.184±0.124 | 0.157±0.078 | 1.790±1.087 |

FIS, deficiency of heterozygosity relative to the Hardy-Weinberg expectation; FIT, the overall inbreeding coefficient; FST, differentiation among populations; Nm, gene flow. SD, standard deviation.

FST values between paired populations ranged from 0.022 to 0.267. The highest level of genetic differentiation was between breed T and breed TF(FST=0.267), and the lowest was between breed CK and breed JY (FST=0.022, Table 7).

Table 7. Estimated pairwise FST values for nine chicken breeds and between three regions.

| Population | High group |

Middle group |

Low group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | G | CK | JY | PY | DH | TF | GS | WC | |

| High group | T | — | |||||||

| G | 0.093*** | ||||||||

| Middle | CK | 0.129*** | align="center"0.057*** | ||||||

| group | JY | 0.124*** | 0.060*** | 0.022*** | |||||

| PY | 0.262*** | 0.249*** | 0.234*** | 0.233*** | |||||

| Low group | DH | 0.229*** | 0.217*** | 0.199*** | 0.192*** | 0.064*** | |||

| TF | 0.267*** | 0.254*** | 0.242*** | 0.236*** | 0.067*** | 0.053*** | |||

| GS | 0.119*** | 0.054*** | 0.028*** | 0.025*** | 0.220*** | 0.178*** | 0.225*** | ||

| WC | 0.114*** | 0.034*** | 0.081*** | 0.086*** | 0.249*** | 0.218*** | 0.258*** | 0.074*** | |

P <0.001.

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

Date summarized in Table 8 indicated that no marker matched Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The Jiuyuan chicken (JY) only had five loci deviated Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. In contrast, Pengxian yellow chicken (PY) had sixteen loci deviated Hard-Weinberg equilibrium.

Table 8. Results of Hardy-Weinberg tests.

| Marker | High group |

Middle group |

Low group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | G | CK | JY | PY | DH | TF | GS | WC | |

| LEI0166 | 1.89 | 6.33 | 23.71** | 23.47 | 15.28 | 31.47 | 5.32 | 0.83 | 4.79 |

| MCW0014 | 75.07** | 15.89* | 11.64 | 4.36 | 71.76*** | 32.06 | 92.78*** | 62.06*** | 26.83* |

| MCW0069 | 23.55 | 47.28 | 46.93*** | 18.25 | 67.66*** | 74.38* | 39.53 | 81.81* | 107.48*** |

| MCW0103 | 3.10 | 62.13*** | 27.65*** | 0.37 | 3.45 | 74.37*** | 3.88 | 26.68*** | 32.39*** |

| MCW0037 | 6.79 | 13.26* | 5.35 | 63.49*** | 37.10*** | 3.75 | 8.43 | 3.06 | 3.13 |

| MCW0330 | 69.26*** | 21.75 | 42.35* | 63.45** | 73.71*** | 37.94* | 11.05 | 68.99*** | 36.98** |

| LEI0094 | 17.34** | 90.00* | 61.07 | 67.23 | 93.13*** | 88.43 | 72.13 | 112.28 | 79.737 |

| MCW0216 | 5.97 | 2.11 | 3.15 | 1.60 | 1.54 | 50.79*** | 5.51 | 2.17 | 15.37 |

| LEI0234 | 17.11 | 212.25** | 131.52 | 185.52** | 146.55*** | 187.76** | 309.53*** | 226.96 | 59.51 |

| MCW0078 | 1.88 | 6.65 | 4.31 | 5.44 | 30.46*** | 36.31*** | 40.08*** | 33.47** | 96.47*** |

| MCW0206 | 10.30 | 3.33 | 10.34 | 20.46** | 41.19** | 60.91*** | 34.64*** | 67.74*** | 63.51*** |

| ADL0112 | 18.57* | 30.00*** | 2.67 | 38.01*** | 39.71** | 60.25*** | 63.23*** | 60.36*** | 58.00*** |

| LEI0192 | 95.56*** | 43.60 | 145.49*** | 50.49 | 83.48*** | 72.55** | 237.30*** | 59.96 | 38.35 |

| ADL0268 | 18.63** | 18.34* | 11.61 | 9.96 | 19.36* | 34.87** | 41.76** | 29.37* | 27.65** |

| MCW0222 | 8.13 | 32.65*** | 6.86 | 0.95 | 34.99* | 26.33* | 39.23*** | 6.43 | 1.344 |

| MCW0034 | 63.90* | 122.40*** | 92.37* | 16.81 | 72.61*** | 78.38 | 108.38* | 182.72*** | 51.74 |

| MCW0111 | 10.11 | 26.03*** | 11.64 | 14.06 | 62.50*** | 65.16*** | 37.21** | 39.55** | 51.13*** |

| MCW0067 | 13.88 | 18.64* | 30.02*** | 23.51 | 60.84*** | 57.77*** | 62.12*** | 44.79** | 36.65** |

| MCW0295 | 30.72 | 44.30*** | 15.50 | 19.79 | 79.61*** | 6.54 | 83.82*** | 56.48** | 24.54 |

P <0.05

P <0.01

P <0.001.

Genetic Difference and Distance among Breeds

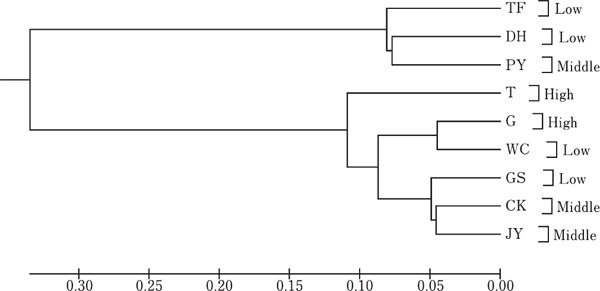

Table 9 showed DA genetic distance among nine breeds. The genetic distance ranged from 0.090 (G from high group and WC from low group) to 0.704 (G from high group and TF from low group). Fig. 2 displayed a phylogenetic tree constructed with DA genetic distances. The average genetic diversity was 0.418. Nine local breeds clustered into 2 groups. Tassel first chicken, Da ninghe chicken and Penxian yellow chicken were clustered in one group. The others were clustered in another group, and formed a close group with Tibetan chicken. There was no geographic specificity in the phylogenetic tree.

Table 9. Nei's DA genetic distance (Nei et al., 1983) among populations.

| Population | High group |

Middle group |

Low group |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | G | CK | JY | PY | DH | TF | GS | WC | ||

| High group | T | — | ||||||||

| G | 0.181 | — | ||||||||

| Middle group | CK | 0.274 | 0.171 | — | ||||||

| JY | 0.242 | 0.171 | 0.091 | — | ||||||

| PY | 0.682 | 0.696 | 0.658 | 0.670 | — | |||||

| Low group | DH | 0.665 | 0.680 | 0.649 | 0.653 | 0.154 | — | |||

| TF | 0.679 | 0.704 | 0.663 | 0.677 | 0.156 | 0.167 | — | |||

| GS | 0.214 | 0.155 | 0.106 | 0.092 | 0.641 | 0.626 | 0.651 | — | ||

| WC | 0.204 | 0.090 | 0.184 | 0.190 | 0.687 | 0.679 | 0.693 | 0.170 | — | |

Fig. 2.

UPGMA (Unweighted Pair-Group Method with Arithmetic Mean) dendrogram of genetic among nine chicken breeds based on DA genetic distances estimated with 19 microsatellites. Numbers on the nodes are bootstrap values of 1000 replications.

Discussion

Our results revealed that a total of 324 alleles were identified in 256 individuals from 9 chicken populations via the 19 microsatellites scanning method. The loci (primers MCW0103) had the poorest polymorphism. Ninety-five present of PIC was more than 0.5. We can draw a conclusion that 19 microsatellites loci were highly polymorphic (Schumm et al., 1988). The population we determined in the current study did not suffer severe genetic bottlenecks. LEI0234 locus had the highest PIC (0.928), which had the larger heterozygous proportion and more genetic information than other microsatellites loci (Wu et al., 2004). All of the nine chicken breeds had high heterozygosity (He>0.5, Ho> 0.5), which meant that genetic variation was large and inbreeding degree was weak (Pariset et al., 2003).

AMOVA results revealed there's no genetic variation among the groups from high, middle and low altitude regions (0% of the total variation) and high level of variation with individuals among populations (80%). These results suggested that geographic isolation among these groups has been broken, and it could not play critical roles in the genetic differentiation among populations. Among the nine groups, there was no significant genetic structure difference; because the local breeds were facing the blow of increasing gene exchange frequency resulted by the convenient transportation.

With the 19 loci examined the mean inbreeding coefficient within individual populations and among all individuals of the loci (except LEI0166, MCW0069, ADL0112, ADL 0268, MCW0111 and MCW0067) were positive, which indicated that the nine local breeds can't avoid heterozygosity loss and there existed inbreeding in these local populations. In all loci, the differentiation among populations (FST) were more than 0.05, the average of FST was 0.157. Our results suggested that among varieties there was a low degree of genetic differentiation. Meanwhile the pairwise FST value showed that altitude had little influence on FST. Wright's (1943) infinite-island approximation indicated that FST=1/ (1+4Nm), thus, the Nm=1.790. Wright pointed out that if Nm<1, genetic drift could lead to significant genetic differentiation between populations, and reducing the genetic variation. Kimura and Weiss (1964) had shown that when Nm≥4, the homogenizing effect of gene flow was sufficient to prevent stochastic differentiation of allele frequencies. Under such conditions, local adaptation may not be constrained by low levels of gene flow that produce a spatial averaging of fitness variation among different altitudes.

Heterozygote deficiency resulted in deviated Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for all loci. Pengxian yellow chicken (PY) from middle group had sixteen loci deviate Hard-Weinberg equilibrium, which may be influenced by selection, migration, mutation or genetic drift.

The genetic distance was the basis for studying on genetic diversity; it reflected the genetic differentiation of investigated populations. The closer group clustered, the smaller genetic distance existed. The genetic distance between nine groups ranged from 0.090 to 0.704, which didn't completely range in the genetic distances (0.2<DA<0.8) between species (Thorpe et al., 2003).The result of the cluster analysis demonstrated that there was no significant altitudinal effect on breeds, which was in accord with the earlier finding which reported altitude effect on microsatellite variation was limited (Zhang et al., 2006). The Tassel first chicken, Da ninghe chicken and Penxian yellow chicken had closer genetic relationship, which may be resulted by gene exchange due to close geographical distance. Tibetan chicken located in another group with relatively far distance with populations G, WC, CK, GS, and JY. Some studies indicate that Tibetan chicken has developed effective strategies through specific physiological and genetic adaptations to survive at high altitude, particularly to address the low-oxygen hypoxic environment (Storz et al., 2010). In addition, Wang et al. (2015) finding the size of their olfactory receptor gene family was reduced, which attributed possibly to adaptation to a highland environment where food sources and odorants are limited.

Our results indicate that genetic variations were mainly made up of the variations among populations and within individuals. There were rich gene diversities in the populations for the detected loci. Meanwhile, frequent genes exchange existed among the populations. This can lead to extinction of the peripheral species, such as the Tibetan chicken breed.

Acknowledgment

The work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No: 31402070), The China Agriculture Research System (CARS-41), and the Science and Technology Bureau of Chengkou county, Chongqing, P. R. China. We deeply appreciated Qigui Wang, from Poultry Institute, Chongqing Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and Jian Sun, from Henan Sangao Agricultural and Animal Husbandry Limited Company provided the sample bloods of Chengkou mountainous chicken, Jiuyuan chicken, Da ninghe chicken, Tassel first chicken, and Gushi chicken.

References

- Cortellini V, Cerri N, Verzeletti A. Genetic variation at 5 new autosomal short tandem repeat markers (D10S1248, D22S 1045, D2S441, D1S1656, D12S391) in a population-based sample from Maghreb region. Croatian Medical Journal, 52: 368-371. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoren J, Vanek D, Konjhodzić R, Crews J, Huffine E, Parsons TJ. Highly effective DNA extraction method for nuclear short tandem repeat testing of skeletal remains from mass graves. Croatian Medical Journal, 48: 478-485. 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gämperle E, Schneller JJ. Phenotypic and isozyme variation in Cystopteris fragilis (Pteridophyta) along an altitudinal gradient in Switzerland. Flora - Morphology Distribution Functional Ecology of Plants, 197: 203-213. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Weiss GH. The Stepping Stone Model of Population Structure and the Decrease of Genetic Correlation with Distance. Genetics, 49: 561 1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei MF, Tajima F, Tateno Y. Accuracy of estimated phylogenetic trees from molecular data. II. Gene frequency data. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 19: 153-170. 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariset L, Savarese MC, Cappuccio I, Valentini A. Use of microsatellites for genetic variation and inbreeding analysis in Sarda sheep flocks of central Italy. Journal of Animal Breeding & Genetics, 120: 425-432. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Premoli AC. Genetic variation in a geographically restricted and two widespread species of South American Nothofagus. Journal of Biogeography, 24: 883-892. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Peakall R, Smouse PE. GenAlEx 6.5. Bioinformatics, 28: 2537-2539. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JW, Knowlton RG, Braman JC, Barker DF, Botstein D, Akots G, Brown VA, Gravius TC, Helms C, Hsiao K. Identification of more than 500 RFLPs by screening random genomic clones. American Journal of Human Genetics, 42: 143-159. 1988. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz-Romero C, Tapia-Olivares BL. Pinus oocarpa isoenzymatic variation along an altitudinal gradient in Michoacán, México. Silvae Genetica, 52: 237-240. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Roessli D, Exco EL. Arlequin: a software for population genetic analysis[C]// LILOG. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Storz JF, Scott GR, Cheviron ZA. Phenotypic plasticity and genetic adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia in vertebrates. Journal of Experimental Biology, 213: 4125-4136. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe JP. The Molecular Clock Hypothesis: Biochemical Evolution, Genetic Differentiation and Systematics. Annual Review of Ecology & Systematics, 13: 139-168. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tadano R, Sekino M, Nishibori M, Tsudzuki M. Microsatellite marker analysis for the genetic relationships among Japanese long-tailed chicken breeds. Poultry Science, 86: 460-469. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. Genetical Structure of populations. Nature, 15: 323-354. 1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmers K, Ponsuksili S, Hardge T, Vallezarate A, Mathur PK, Horst P. Genetic distinctness of African, Asian and South American local chickens. Animal Genetics, 31: 159-165. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen CS, Hsiao JY. Altitudinal Genetic Differentiation and Diversity of Taiwan Lily (Lilium longiflorum var. formosanum; Liliaceae) Using RAPD Markers and Morphological Characters. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 162: 287-295. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wu SB, Collins G, Sedgley M. A molecular linkage map of olive (Olea europaea L.) based on RAPD, microsatellite, and SCAR markers. Genome, 47: 26-35. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MS, Li Y, Peng MS, Zhong L, Wang ZJ, Li QY, Tu XL, Dong Y, Zhu CL, Wang L, Yang MM, Wu SF, Miao YW, Liu JP, Irwin DM, Wang W, Wu DD, Zhang YP. Genomic Analyses Reveal Potential Independent Adaptation to High Altitude in Tibetan Chickens. Molecular Biology & Evolution, 32: 1880-1889. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Korpelainen H, Li C. Microsatellite variation of Quercus aquifolioides populations at varying altitudes in the Wolong natural reserve of China. Silva Fennica, 40: 407-415. 2006. [Google Scholar]