Abstract

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) hold great therapeutic potential, in part because of their immunomodulatory properties. However, these properties can be transient and depend on multiple factors. Here, we developed a multifunctional hydrogel system to synergistically enhance the immunomodulatory properties of MSCs, using a combination of sustained inflammatory licensing and three-dimensional (3D) encapsulation in hydrogels with tunable mechanical properties. The immunomodulatory extracellular matrix hydrogels (iECM) consist of an interpenetrating network of click functionalized-alginate and fibrillar collagen, in which interferon γ (IFN-γ) loaded heparin-coated beads are incorporated. The 3D microenvironment significantly enhanced the expression of a wide panel of pivotal immunomodulatory genes in bone marrow-derived primary human MSCs (hMSCs), compared to two-dimensional (2D) tissue culture. Moreover, the inclusion of IFN-γ loaded heparin-coated beads prolonged the expression of key regulatory genes upregulated upon licensing, including indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) and galectin-9 (GAL9). At a protein level, iECM hydrogels enhanced the secretion of the licensing responsive factor Gal-9 by hMSCs. Its presence in hydrogel conditioned media confirmed the correct release and diffusion of the factors secreted by hMSCs from the system. Furthermore, co-culture of iECM-encapsulated hMSCs and activated human T cells resulted in suppressed proliferation, demonstrating direct regulation on immune cells. These data highlight the potential of iECM hydrogels to enhance the immunomodulatory properties of hMSCs in cell therapies.

Keywords: MSCs, immunomodulation, interferon, extracellular matrix, hydrogel, alginate

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are attractive candidates for the treatment of inflammatory and immune disorders. MSCs can regulate both innate and adaptive immunity by suppressing maturation, proliferation and activation of immune cells [1], including monocytes and macrophages [2,3], dendritic cells [4] and T, B and natural killer (NK) lymphocytes [5–7]. MSCs mediate these effects via different mechanisms, including direct cell-cell contact and the release of bioactive soluble factors, such as interleukins, metabolic enzymes or growth factors. The paracrine effects of released agents are considered a primary mechanism of MSC immunomodulation [8–10].

However, MSC mediated immunomodulation depends on various environmental factors. To enhance the regulatory potential of MSCs, researchers have explored a number of approaches. MSC licensing with inflammatory signals such as interferon γ (IFN-γ) or tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) promotes an immunosuppressive phenotype and enhances secretion of bioactive factors, but these effects are transient [11–13]. Three-dimensional (3D) cell culture has also been reported to affect the immunomodulatory properties of MSCs [14]. The formation of cell spheroids enhances cell-cell contact and can boost the immunomodulatory potential of MSCs [15,16]. Additionally, the mechanical properties of the extracellular microenvironment also influence MSC biology, as the expression of immunomodulatory markers is differentially influenced by the stiffness and viscoelasticity of the matrix [17].

Here, we developed a multifunctional system for the encapsulation of bone-marrow derived primary human MSCs (hMSCs) as an integrated solution to enhance their immunomodulatory properties. This system combines sustained inflammatory licensing and 3D biomimetic cell culture in artificial extracellular matrix (aECM) hydrogels. The matrix of aECM hydrogels consists of an interpenetrating network of alginate and fibrillar collagen type I. Presentation of collagen-I matrix in the hydrogels mimics the collagen-rich architecture of native extracellular matrix (ECM), which promotes hMSCs survival [18]. Viscoelasticity and stiffness were independently tuned by varying the mode and magnitude of alginate crosslinking. Viscous alginate hydrogels exhibit rapid stress-relaxation behavior as a result of the reversible ionic crosslinks at blocks of guluronic acid-rich regions (i.e., G-blocks). Reinforcement of G-blocks by permanent covalent crosslinking imparts more elastic properties with the incorporation of norborene (Nb) and tetrazine (Tz), which undergo bio-orthogonal inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reactions to “click” together the existing G-block ionic crosslinks [17,19]. Four types of aECM hydrogels were investigated and termed: soft viscous, stiff viscous, soft elastic and stiff elastic, which were previously characterized [17]. Sustained inflammatory licensing was achieved by incorporating IFN-γ loaded heparin-coated beads in aECM. We termed these composite systems immunomodulatory extracellular matrix (iECM) hydrogels. The gene expression of a panel of immunomodulatory markers, including indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), galectin 9 (GAL9), prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 / Cyclooxygenase 2 (PTGS2), interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL1RN), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and interleukin-10 (IL10) was used to provide broad insight on the effects of this combinatorial approach on the immunomodulatory properties of hMSCs. These genes were selected because they are translated to bioactive factors that play distinct roles in the regulatory response and are influenced by different stimuli [1,20–25]. Furthermore, levels of soluble factors released by hMSCs were measured and their capacity to inhibit human T cell proliferation was evaluated to study the direct immunomodulatory effect of iECM-encapsulated hMSCs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell isolation and culture

hMSCs were obtained from human bone marrow from donors less than 45 years old. Their characteristics have been detailed in Supplementary Table S1. After acquiring the fresh bone marrow (Lonza), hMSCs were isolated by means of a density gradient using Lymphoprep (StemCell Technologies) and were subsequently seeded onto tissue culture treated flasks. After 2 passages, the adherent cells were detached and cryopreserved in complete media and 7.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Thermo). hMSCs were grown in complete media, which consists on minimum essential medium α (α-MEM) (no nucleosides, +GlutaMax, Gibco) supplemented with 20 % heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HIFBS) and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) (Thermo). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 / 95 % air atmosphere and passaged every 3 – 7 days at 70 – 90 % confluence. For all experiments, cells were used between passage 2 – 4.

2.2. Click alginate polymer synthesis

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Low molecular weight (MW ~ 32 kDa), ultra-pure very low viscosity sodium alginates (UP-VLVG) (Pronova) were purchased from NovaMatrix. These were used unmodified or click modified with norborene (Nb) or (4-(1,2,4,5-Tetrazin-3-yl)phenyl)methanamine- Trifluoroacetic acid (Tz). While Nb was commercially available (Nb Methanamine, TCI America), the synthesis of Tz was carried out as previously described [19]. Briefly, 50 mmol of 4- (aminomethyl)benzonitrile hydrochloride and 150 mmol formamidine acetate were stirred with 1 mol of anhydrous hydrazine at 80 °C for 45 min and quenched using 0.5 mol of sodium nitrite. Subsequently, the product was isolated sequentially in 10 % HCl and NaHCO3 and extracted with dichloromethane (DCM). The final product was recovered by rotary evaporation and purified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

To obtain click-modified UP-VLVG, a covalent coupling of either Tz or Nb was performed [19]. Briefly, UP-VLVG alginate was dissolved in pH 6.5 buffer (0.1 M MES, 0.3 M NaCl) at 1 % w/v. Next, N-hydroxysuccinimide(NHS)and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimidehydrochloride (EDC) were added in 5 X molar excess of the carboxylic acid groups of alginate. Finally, either Nb or Tz was incorporated at 1 mmol per gram of alginate. The coupling reaction was stirred at room temperature for 16 h and then quenched with hydroxylamine. The product was centrifuged and purified via tangential flow filtration using a 1 kDa molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) column (Spectrum Labs) against a decreasing salt gradient from 150 mM to 0 mM NaCl in de-ionized water. The purified Alg-Tz or Alg-Nb polymers were treated with activated charcoal, sterile filtered (0.22 μm), and freeze-dried for long-term storage. The resulting modified alginates present a 5 % degree of substitution, which refers to 5 % of available carboxylic acid groups modified with Nb or Tz per mol of low molecular weight alginate (MW = 32 kDa).

2.3. Cell encapsulation in aECM or iECM hydrogels

aECM hydrogels were fabricated as previously described, with slight modifications[17]. Briefly, alginate and collagen solutions were prepared prior to gel manufacture. A stock solution of collagen (Rat tail telo-collagen, Type I 8–11 mg/mL, Corning) was mixed on ice with 10 X Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) (with phenol red, without calcium and magnesium, Sigma-Aldrich), HEPES 20mM final concentration, (Gibco) and 1M sodium hydroxide (~ 1 % final concentration, NaOH) to pH 5 – 6.5. UP-VLVG was used either unmodified (to obtain “viscous” gels) or modified with Nb (Alg-Nb) or Tz (Alg-Tz) (to obtain “elastic” gels). Alginate solutions were prepared at a 5 % concentration in buffered salt solution (HBSS, 20 mM HEPES), adjusting pH to ≈ 7 with 1 M NaOH. To obtain a calcium carbonate (CaCO3) slurry (100 mg mL−1), precipitated calcium carbonate nanoparticles (nano-PCC, Multifex-MM, Specialty Minerals) were suspended in sterile water for injection (Gibco) and ultrasonicated (70 % amplitude, 15 s). hMSCs for encapsulation were licensed overnight (≈ 16 h) by supplementing the culture media with IFN-γ (20 ng mL−1) and TNF-α (10 ng mL−1). On the day of cell encapsulation, hMSCs were retrieved from culture, suspended at 40 × 106 cells mL−1 in HBSS/HEPES and maintained on ice before use.

Hydrogels were fabricated on ice with continuous mixing by a micro-stir bar to ensure homogeneously distributed components. First, the calcium carbonate slurry was incorporated into the collagen solution, and an appropriate volume of stock cell solution was added to obtain a desired final concentration of 2 × 106 cells mL−1. Next, alginate was added to the mixture. For viscous hydrogels, unmodified alginates were used, whereas for elastic hydrogels, click-modified alginates, Alg-Nb and Alg-Tz, were used as well. The ratio of Alg-Nb to Alg-Tz was adjusted depending on the calcium condition, as indicated in Table 1. For elastic gels, unmodified UP-VLVG and Alg-Nb were mixed with the collagen and calcium slurry, and Alg-Tz was reserved to add at the last step. Once all the components were appropriately mixed, freshly dissolved glucono-delta-lactone (GDL) was added (EMD Millipore, 0.4 g mL−1 in HBSS/HEPES). For elastic gels, lastly, the reserved Alg-Tz was incorporated. For the preparation of iECM hydrogels, agarose beads coated with heparin (BioRad) were added in the hydrogels as a final step. The beads, 232.35 ± 34.19 μm in diameter, were loaded with IFN-γ following incubation in 80 ng mL−1 solution of the cytokine for 1 h at 37 °C. Final concentrations of each component of the hydrogels are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

aECM hydrogel formulations.

| Collagen (mg/mL) | VLVG alginate (% w/v) | Nb-alginate (% w/v) | Tz-alginate (% w/v) | Total alginate (% w/v) | CaCO3 (% w/v) | GDL (mM) | G’ (Pa)* | G” (Pa)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viscous soft | 4 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 40 | 250 | 32 |

| Viscous stiff | 4 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 120 | 2500 | 230 |

| Elastic soft | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 40 | 250 | 18 |

| Elastic stiff | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 120 | 2500 | 90 |

Nb, norborene. Tz, tetrazine. VLVG, very low viscosity. GDL, glucono-delta-lactone.

from [17]

The resulting hydrogel mixture was rapidly pipetted to untreated 12 well plates to cast hydrogels of 250 μL (at a cell density of 2 × 106 cells mL−1), which were incubated 1 h at 37 °C for gelation. Afterwards, 1 mL of buffered salt solution (HBSS, 20 mM HEPES) was added to each well and hydrogels were equilibrated for another hour at 37 °C. The buffer pH was monitored and replaced with fresh buffer when the pH dropped below 7. Finally, the buffered salt solution was exchanged for 1 mL of fresh α-MEM supplemented with 10 % HIFBS and 1 % P/S. The hydrogel-encapsulated cells were cultured at 37 °C, 5 % CO2. Control, tissue culture plate (TCP) 2D seeded hMSCs were cltured under the same conditions.

2.4. Cell retrieval

To retrieve cells, hydrogels were incubated at 37 °C with 250 μL of digestion solution containing 34 U mL−1 alginate lyase (Sigma-Aldrich) and 300 U mL−1 collagenase type I (Sigma-Aldrich). After 20 min, the hydrogels were mechanically disrupted by pipetting and an extra 250 μL of fresh digestion mixture was added. The gels were incubated at 37 °C for an additional 20 min.

Next, 0.1 mL of wash buffer (DPBS w/o Ca/Mg, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5 % BSA) was added and the entire mixture was transferred from the culture plates to low protein binding Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and two additional washes were performed. The cell number and viability were assessed using a benchtop cell analyzer (MUSE), before the addition of RNA lysis buffer (Invitrogen), supplemented with 1 % β-mercaptoethanol. After vortexing, samples were stored at −80 °C until use.

2.5. Relative gene expression measurement

RNA isolation and purification were performed with PureLink RNA Micro-scale Kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quantity and quality were assessed by NanoDrop spectrophotometer, and cDNA was reverse-transcribed by iScript Advanced Reverse Transcription Supermix for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) (Bio-Rad). RT-qPCR was carried out using a CFX96 instrument (Bio-Rad). Samples were run in duplicate with 10 ng of cDNA, 2× Advanced SSO SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and Bio-Rad PrimePCR primers in each reaction. Relative gene expression was computed via the delta Ct method using a reference gene (GAPDH). The list of individual gene primers is shown in Supplementary Table S2.

2.6. Quantification of the heparin-coated bead IFN-y load

To quantify the IFN-γ loaded in the iECM hydrogels, heparin-coated beads were incubated in an 80 ng ml−1 solution of IFN-γ for 1 h at 37 °C. Afterwards, the beads were decanted and the supernatant was collected to assess the amount of free IFN-γ remaining in the solution. A human IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to quantify the amount of unbound cytokine (Biolegend, human IFN-γ ELISA MAX™ Set Deluxe) and compared to the equivalent amount of IFN-γ incubated without beads.

2.7. Luminex assay on conditioned media

hMSCs were encapsulated in aECM or iECM hydrogels (250 μL of hydrogel volume at a cell density of 2 × 106 cells mL−1) and maintained in culture with 1 mL of α-MEM supplemented with 10 % HIFBS and 1 % P/S at 37 °C, 5 % CO2. At day 3, the resulting conditioned media was collected and replaced with 1 mL of fresh media, which was collected at day 7. Conditioned media was stored at 80°C. For analysis, conditioned media was thawed, centrifuged at 16,000×g for 4 min and the supernatant was diluted two-fold. Measurements of Gal-9 and IL-1Ra in diluted samples were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions for Luminex (R&D). Concentrations of each sample were obtained from standard curves for each analyte by a five-parameter logistic (5PL) curve fit.

2.8. Primary T cell isolation and co-culture with hMSCs encapsulated in iECM

Primary human T cells were obtained from de-identified leukoreduction collars (Brigham and Women’s Hospital Specimen Bank) and used within 24 h of initial collection (stored at room temperature (RT). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were enriched from leukoreductions in a Ficoll gradient, and then isolated using a pan human T cell MACS kit (Miltenyi Biotec) to obtain CD3+ T cells for polyclonal expansion. Dynabeads (ThermoFisher Scientific) were used for T cell activation, according to the manufacturer-optimized protocol. T cells were initially seeded at 1x105 cells in the starting culture with pre-washed Dynabeads at 1:1 bead-to-cell ratio in T cell media supplemented with 30 U/mL recombinant IL-2 (Biolegend). Fresh IL-2-supplemented media was added throughout culture to maintain the cell density between 0.5–1x106 cells/mL. T cells were cultured for 7 days, then stained with CFSE (1:10,000, ThermoFisher Scientific) prior to hMSC co-culture. Following CFSE-labeling, T cells were seeded at 2.5x105 cells/mL with 2x105 hMSCs encapsulated in iECM hydrogels, in 12-well MatTek dishes (4 days after hMSCs encapsulation). T cells were retrieved 3 days after co-culture for flow cytometry staining and analysis. T cells were stained with dead cell stain (Thermo) prior to blocking with FcRx and staining with anti-CD3-PerCP-Cy5.5 (Biolegend). Flow analysis was performed on a BDFortessa with compensation.

2.9. Data analysis and statistics

Statistical computations were performed using SPSS 23 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL) and Prism GraphPad software. The normal distribution of the data was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For comparisons between two groups, the parametric Student’s t-test was used for normally distributed data and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data. For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA was performed, using Levene’s test to determine the homogeneity of variances. If homogeneous, the Tukey post-hoc test was applied, otherwise the Tamhane post-hoc test was used. P-values less than 0.05 were assumed to be significant in all analyses. The statistical studies of RT-qPCR data were performed using the delta-Ct values.

3. Results

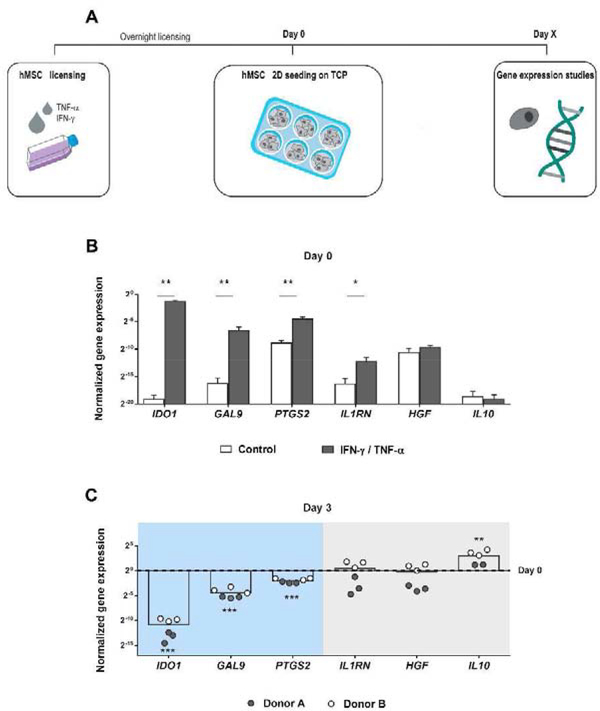

First, 2D tissue culture was used to confirm the effects of inflammatory licensing on the expression of relevant immunomodulatory genes. Following the experimental procedure shown in Fig. 1A, hMSCs were licensed overnight (≈ 16 h) with IFN-γ and TNF-α. Gene expression assessment immediately after licensing (day 0) demonstrated that pre-treatment with cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α upregulated IDO1, GAL9, PTGS2 and IL1RN in comparison to non-treated cells. However, using this cytokine regime, HGF and IL10 were unaffected (Fig. 1B). After 3 days of 2D culture, the expression of the upregulated genes was significantly reduced compared to the initial levels (Fig. 1C), except for IL1RN, which, like HGF and IL10, did not show a reduction once the effect of overnight licensing was lost. Therefore, we classified the gene panel into two groups, namely: genes responsive to inflammatory licensing (IDO1, GAL9, PTGS2), which were upregulated by licensing but their expression decreased when the effect was exhausted; and genes not responsive (IL1RN, HGF, IL10), which did not decrease after the transient effect of licensing.

Fig. 1. Immunomodulatory gene expression by 2D tissue cultured hMSCs on day 3.

(A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure. After hMSC overnight licensing with IFN-γ and TNF-α, cells were detached and 2D seeded on tissue culture plates (TCP). At different time-points, RNA was isolated from the cells for the subsequent RT-qPCR analysis. (B) Normalized gene expression of IDO1, GAL9, PTGS2, IL1RN, HGF and IL10 by tissue culture hMSCs after overnight licensing with IFN-γ and TNF-α compared to control untreated cells. Normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. * Statistically significant difference between control and licensed hMSCs, Studenťs T test, unpaired. p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (C) Normalized gene expression of IDO1, GAL9, PTGS2, IL1RN, HGF and IL10 by hMSCs on tissue culture 3 days after overnight licensing with IFN-γ and TNF-α. Normalized to GAPDH and day 0 expression. * Statistically significant difference between day 0 and day 3, Studenťs T test, unpaired for IDO1, GAL9, PTGS2, HGF and IL10. Mann–Whitney U test for IL1RN. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01. hMSCs, human mesenchymal stromal cells. IFN-γ, interferon γ. TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

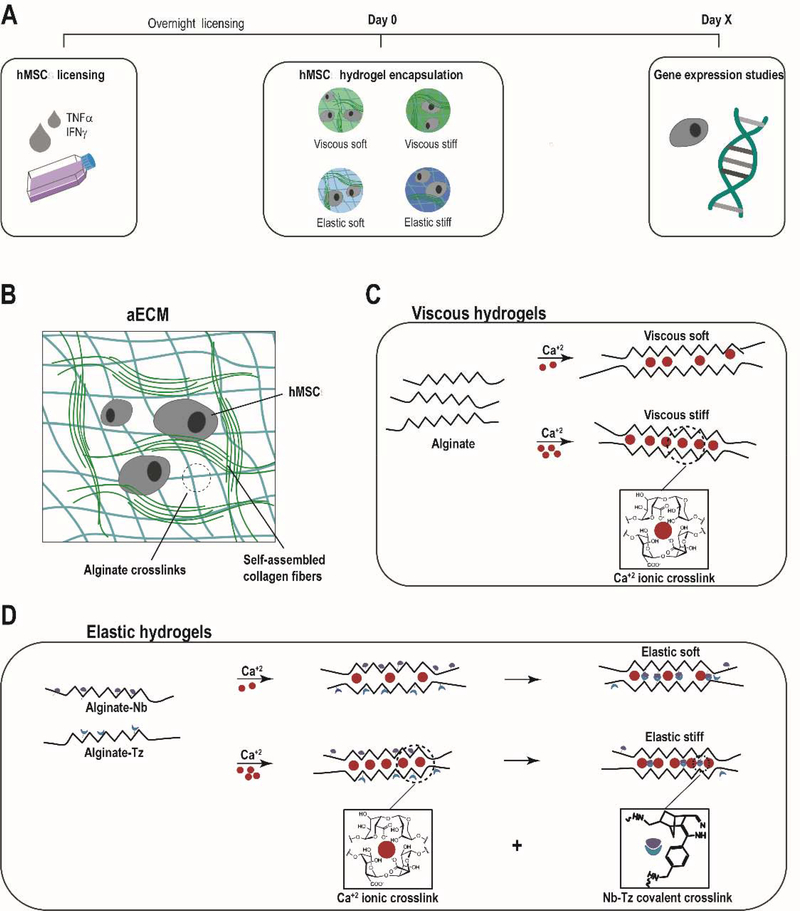

We next asked whether cell encapsulation in an appropriate 3D hydrogel could maintain expression of immunomodulatory genes. hMSCs were encapsulated in a range of aECM hydrogels after overnight licensing (Fig. 2A). In particular, four types of aECM hydrogels were tested: soft viscous, stiff viscous, soft elastic and stiff elastic (Fig. 2 B–D). Their formulation is 231 shown in Table 1.

Fig. 2. aECM hydrogels.

(A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure. After hMSC overnight preconditioning with IFN-γ and TNF-α, cells were detached and 3D encapsulated in aECM hydrogels. At different time-points, RNA was isolated from the cells for the subsequent RT-qPCR analysis. (B) aECM hydrogel system structure. (C) When alginates were crosslinked with calcium, viscous hydrogels were obtained, (D) whereas the combination of ionic crosslinking and covalent crosslinking between the Norborene and Tetrazine groups led to more elastic gels. aECM, artificial extracellular matrix. Nb, norborene. Tz, tetrazine. hMSCs, human mesenchymal stromal cells.

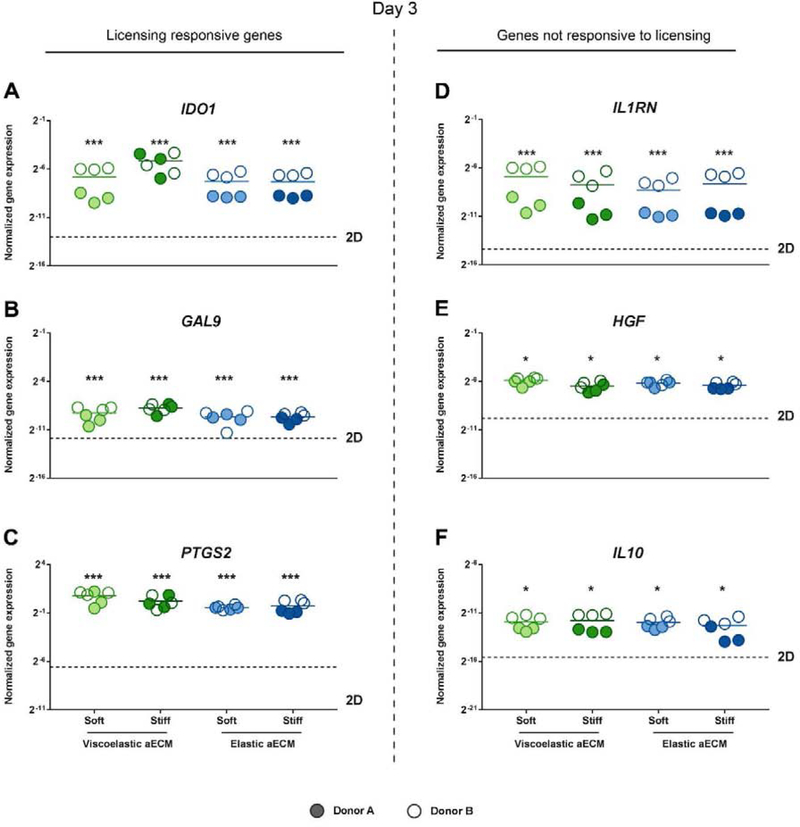

After 3 days, the expression of the panel of immunomodulatory genes in 3D encapsulated cells was significantly higher than in tissue culture (2D), for both, genes classified as responsive (Fig. 3 A–C) or not responsive (Fig. 3 D–F) to inflammatory licensing. To confirm the effects of the 3D encapsulation, non-licensed hMSCs were encapsulated and found to also present an upregulated expression of immunomodulatory genes (Supplementary Fig. S1). Subsequent experiments were conducted with overnight licensed, encapsulated cells, as they expressed higher levels of the cytokine responsive genes than unlicensed hMSCs (Supplementary Fig. S2). No statistically significant differences in gene expression were observed between the four aECM hydrogel types.

Fig. 3. Immunomodulatory gene expression by hMSCs 3D cultured in aECM hydrogels on day 3.

Normalized gene expression of (A) IDO1, (B) GAL9, (C) PTGS2, (D) IL1RN, (E) HGF and (F) IL10 by hMSCs encapsulated within aECM hydrogels 3 days after overnight licensing with IFN-γ and TNF-α and subsequent encapsulation. Normalized to GAPDH. * Statistically significant differences, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test for IDO1, GAL9 and IL1RN; one-way ANOVA with Tamhane’s post hoc test for PTGS2, HGF and IL10. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared to 2D cultured hMSCs. aECM, artificial extracellular matrix. hMSCs, human mesenchymal stromal cells. IFN-γ, interferon γ. TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

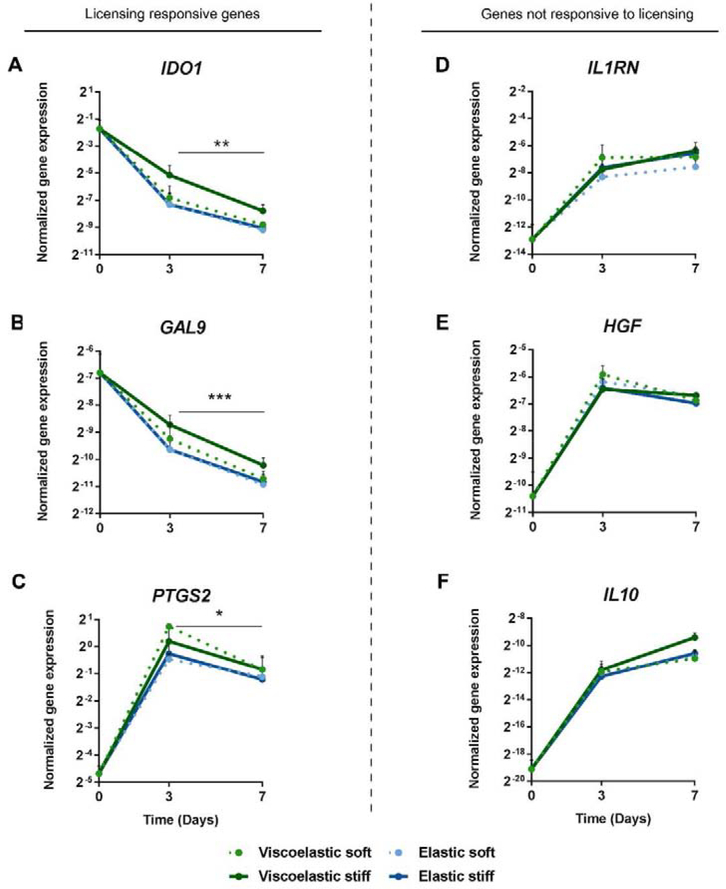

The effects of aECM encapsulation were also analyzed over 7 days, and two different trends in the gene panel were noted. Expression of genes that were strongly responsive to licensing (IDO1, GAL9 and PTGS2) were significantly reduced after 7 days of cell culture in all aECM hydrogels, compared to day 3 (Fig. 4 A–C). Conversely, the expression of genes classified as not responsive to inflammatory licensing (IL1RN, HGF and IL10) increased in expression by day 3, and the increases were maintained at day 7 (Fig. 4 D–F). Similar to previous studies, no cell proliferation was observed in the gels [26]. Again, no statistically significant differences were observed among different aECM hydrogels. Considering that click-crosslinking improves alginate hydrogels’ integrity and stability over-time and can be implanted for months with no sign of degradation [19], we used stiff elastic hydrogels for the following sets of experiments, as they were the most mechanically robust and potentially most relevant for implantation studies.

Fig. 4. Immunomodulatory gene expression by aECM encapsulated hMSCs over time.

Normalized gene expression of (A) IDO1, (B) GAL9, (C) PTGS2, (D) IL1RN, (E) HGF and (F) IL10 by aECM encapsulated hMSCs 0, 3 and 7 days after licensing with IFN-γ and TNF-α and subsequent encapsulation. Normalized to GAPDH. * Statistically significant difference between days 3 and 7, Studenťs T test, unpaired. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. hMSCs, human mesenchymal stromal cells. IFN-γ, interferon γ. TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

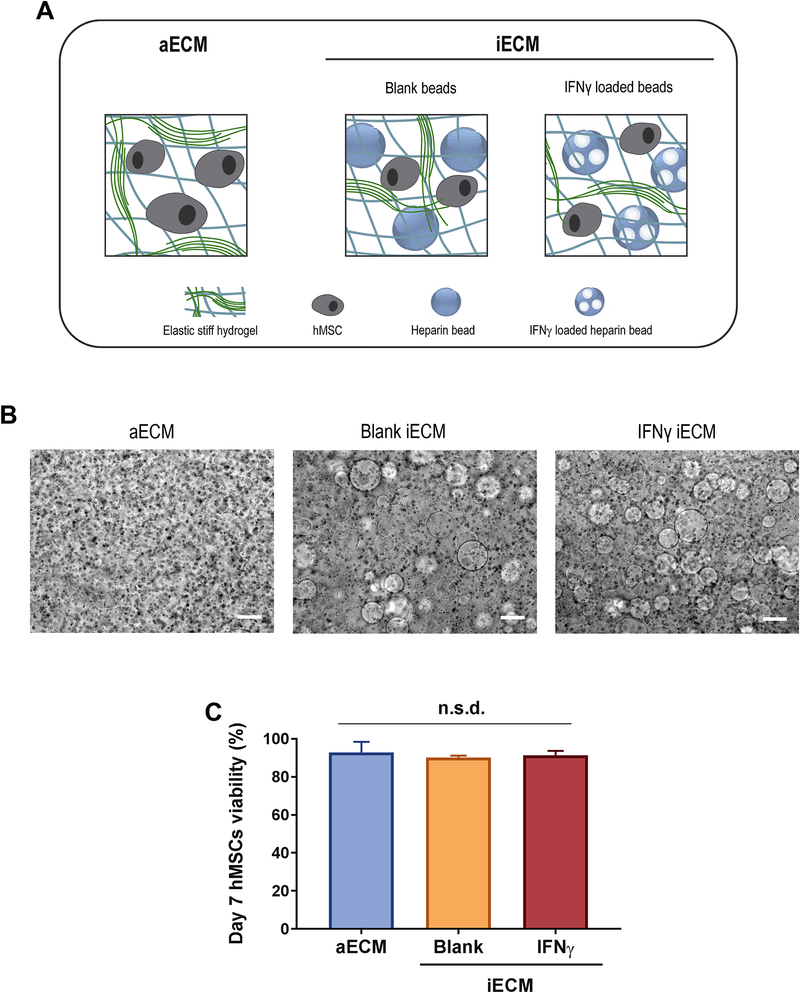

Since IDO1, PGE2 or GAL9 encode for soluble factors that play key roles in mediating the immunoregulatory effects of hMSCs, a strategy was developed to improve the maintenance of expression of these critical genes. We incorporated sustained licensing with IFN-γ within the elastic stiff aECM hydrogel matrix. Hydrogels were fabricated that contained heparin-coated beads loaded with IFN-γ (IFN-γ iECM), and compared to gels with beads that were not loaded with IFN-γ (blank iECM) and to control hydrogels without beads (aECM) (Fig. 5A). Bead incorporation did not significantly affect the cell encapsulation process, as shown by the homogeneity of cells in gels (Fig. 5B). Incorporation of IFN-γ loaded heparin-coated beads in iECM led to a loading of 12.66 ± 2.33 ng of IFN-γ per 0.25 mL of gel. The addition of blank beads and IFN-γ-loaded beads had no significant effect on hMSCs viability in iECM hydrogels after 7 days compared to aECM without beads (Fig. 5C), suggesting that neither heparin-coated beads nor IFN-γ impaired cell function.

Fig. 5. Characterization of the new iECM materials.

(A) Schematic representation of iECM hydrogel types. (B) Phase microscopy images of hMSCs encapsulated in iECM hydrogels. Scale bar = 200 μm. (C) hMSC viability in aECM and iECM hydrogels on day 7 after overnight licensing with IFN-γ and TNF-α and subsequent encapsulation. Normalized to the total cell count in each hydrogel. n.s.d., no significant differences by one-way ANOVA. aECM, artificial extracellular matrix. iECM, immunomodulatory extracellular matrix. IFN-γ, interferon γ. hMSC, human mesenchymal stromal cells.

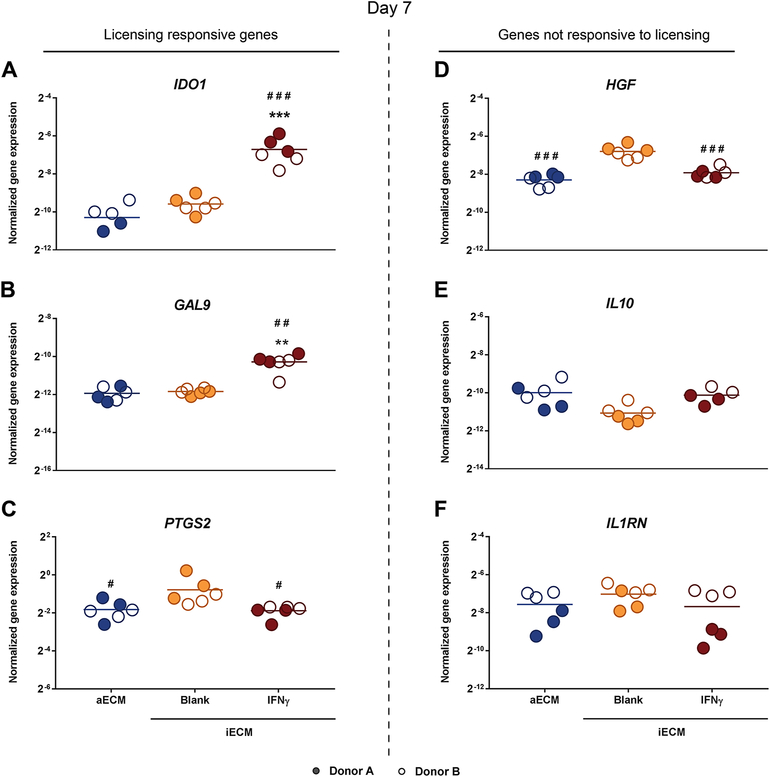

To evaluate the capacity of iECM to improve hMSC licensing, hMSCs were licensed overnight with IFN-γ / TNF-α, encapsulated in aECM or iECM hydrogels and maintained in culture for 7 days. The expression of IDO1 and GAL9, the genes most responsive to inflammatory licensing, significantly increased in IFN-γ-iECM compared to blank iECM and aECM (Fig. 6 A–B). Interestingly, blank iECM hydrogels enhanced the expression of PTGS2 and HGF (Fig. 6 C–D). No differences were observed in the expression of IL10 and IL1RN (Fig. 6 E–F).

Fig. 6. Immunomodulatory gene expression by hMSCs encapsulated in iECM hydrogels on day 7.

Normalized gene expression of (A) IDO1, (B) GAL9, (C) PTGS2, (D) HGF, (E) IL10 and (F) IL1RN by hMSCs encapsulated within iECM hydrogels 7 days after overnight licensing with IFN-γ and TNF-α and subsequent encapsulation. Normalized to GAPDH. Statistical significance by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test for IDO1, PTGS2, HGF, IL10 and IL1RN; one-way ANOVA with Tamhane’s post hoc test for GAL-9. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared to aECM. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 compared to blank iECM. aECM, artificial extracellular matrix. iECM, immunomodulatory extracellular matrix. hMSC, human mesenchymal stromal cells.

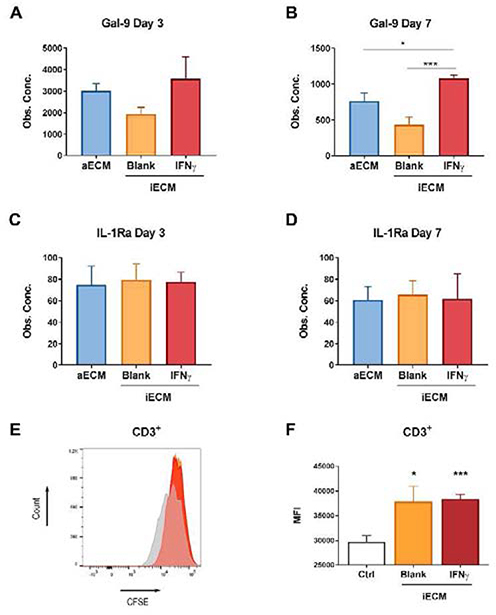

At the protein level, secretion of Gal-9 and IL1-Ra followed the similar trends observed at day 7 in their respective encoding genes, GAL9 and IL1RN (Fig. 7A–D). IDO1 was not measured in conditioned media, because it is an intracellular metabolic enzyme. Gal-9 levels were significantly higher in conditioned media collected from cells encapsulated in IFN-γ-iECM, compared to blank-iECM and aECM at day 7 (Fig. 7B). No significant differences were observed in the levels of IL1-Ra (Fig. 7C–D). Finally, a T cell proliferation assay was performed to confirm that the loaded IFN-γ did not negatively impact hMSC immunomodulation. Overnight licensed hMSCs were cultured in IFN-γ and blank iECM hydrogels for 4 days, followed by co-culture with CFSE-stained human activated T cells for 3 days. The mean fluorescence intensity of CFSE in CD3+ T cells was significantly higher in co-cultured samples compared to tissue culture control, indicating that MSCs encapsulated in iECM hydrogels suppressed T cell proliferation (Fig. 7E–F).

Fig. 7. Immunomodulatory effects of hMSCs encapsulated in iECM hydrogels.

(A-B) Gal-9 and (C-D) IL-1Ra protein levels in hydrogel conditioned media. * Statistically significant differences, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. (E-F) Flow cytometry histogram (E) and mean fluorescence intensity (F) of CFSE-stained T cells co-cultured with IFN-γ or Blank iECM hydrogel encapsulated hMSCs (1:1.25 hMSC:T cell ratio) compared to control without co-culture (Ctrl). iECM: immunomodulatory extracellular matrix. hMSCs: human mesenchymal stromal cells. IFN-γ: interferon γ. Ctrl: control (no hMSC). MFI: mean fluorescence intensity. * Statistically significant differences, Studenťs T test, unpaired. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates a multifunctional system to enhance and prolong the immunomodulatory properties of hMSCs. The effects of 3D cell encapsulation and sustained inflammatory licensing on the expression of a broad panel of immunomodulatory markers was determined. A panel of 6 genes encoding for immune-regulatory factors provided a metric for the immunomodulatory phenotype of MSCs. IDO1, GAL9, PTGS2, IL1RN, HGF and IL-10 were selected since the factors they encode have different contributions in the hMSC-mediated immunomodulatory response [20–25]. Moreover, some of these genes respond to inflammatory cytokines, and some of them do not [1], which enables us to carefully dissect the effects of 3D culture and cell licensing in this combinatorial approach.

The genes IDO1, GAL9 and PTGS2 were upregulated upon overnight inflammatory licensing with IFN-γ and TNF-α, which was consistent with previous studies that showed the combination of these two cytokines polarized hMSCs to an immunosuppressive phenotype [13], inducing the secretion of regulatory enzymes and soluble factors such as IDO and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) [1]. Although not assessed here, previous reports have shown that licensing can enhance the multipotent differentiation capacity of MSCs [27]. IL1RN expression was regulated by inflammatory cytokines to a lesser extent in this study. Furthermore, the effect of overnight licensing was transient, since after 3 days of 2D culture, the expression of IDO1, GAL9 and PTGS2 significantly decreased. In contrast, the expression of IL1RN, HGF and IL-10 were maintained after 3 days. Therefore, these genes were classified into two groups: (1) genes responsive to inflammatory licensing (IDO1, GAL9, PTGS2) showing a transient upregulation upon inflammatory licensing; and (2) genes not responsive (IL1RN, HGF, IL-10), showing stable expression upon inflammatory licensing.

Encapsulation in a 3D hydrogel matrix significantly upregulated hMSC immunomodulatory gene expression over 3 days, as compared to 2D culture. All evaluated genes were upregulated, regardless of whether it was responsive to inflammatory licensing with IFN-α / TNF-α or not. This suggests a strong effect of the 3D biomimetic culture itself, independent of licensing. While the expression of licensing responsive genes IDO1, PTGS2 and GAL9 significantly decreased overtime, the expression of genes not regulated by IFN-γ / TNFα was maintained over 7 days in aECM encapsulated hMSCs, indicating that the effect of 3D culture persisted. Despite previous studies highlighting the impact of mechanical properties of the matrix on MSC biology [26,28,29], no significant differences in hMSC immunomodulatory gene expression were detected among the different aECM hydrogels tested in this study. This may be due to an overwhelming impact of the 3D culture, which when combined with overnight inflammatory licensing, could polarize the cells to an extent such that the differences between the particular mechanical variations tested here were negligible. Further work is required to determine the mechanism by which 3D encapsulation in aECM enhances the immunomodulatory potential of MSCs.

To prolong the expression of licensing-responsive immunomodulatory genes, heparin-coated beads were incorporated in elastic stiff aECM. It was selected for being the most mechanically robust aECM variation, since click-crosslinking makes alginate hydrogels stable over-time [19]. The high affinity of heparin for IFN-γ (KD = 1 – 5 nM) [30] enabled cytokine loading in the beads. The binding of IFN-γ to heparin has been demonstrated to limit the extent of proteolytic degradation to one of its domains, which in turn, enhances potency [30,31]. The multifunctional system composed of elastic stiff aECM and IFN-γ-loaded heparin-coated beads was termed IFN-γ-iECM. The expression of licensing-responsive genes IDO1 and GAL9 was significantly upregulated in IFN-γ-iECM hydrogels by day 7 relative to aECM and blank-iECM, indicating a sustained licensing effect. The upregulation of these two factors could have a great impact in the overall MSC immunomodulation since they have been reported as markers for MSC potency and have been proven to play major roles in the attenuation of some immune mediated diseases [22,32–34]. Furthermore, these data provide a deeper insight on the concept of sustained licensing, which has previously been explored, but not in combination with biomimetic hydrogel culture and limited to IDO1 expression [16]. Since heparin can bind multiple growth factors and cytokines [30,35], we tested iECM hydrogels that incorporated unloaded heparin-coated beads (blank-iECM) as a control to isolate the effect of IFN-γ. Interestingly, PTGS2 and HGF expression was upregulated in blank iECM. Despite this work focused on the ability of IFN-γ to regulate hMSCs behavior, future studies may explore the underlying mechanism of this phenomenon. In the case of IL10 and IL1RN, which were not responsive to licensing, significant differences were not detected between iECM and aECM hydrogels, suggesting that the effect of the matrix in 3D culture was sufficient to maintain their expression.

Analysis of conditioned media showed that the secretion of the licensing responsive factor Gal-9 was significantly enhanced in IFN-γ-iECM hydrogels by day 7, whereas the sustained exposure to IFN-γ did not promote the release of IL-1Ra, confirming the results at the protein level. Furthermore, these results suggest that the hydrogel matrix and heparin-coated beads do not impede release of factors secreted by the encapsulated hMSCs. This is a key feature of the system, because biomaterial formulations have been reported to hamper the biomolecule diffusion by their relatively large volume [28]. Although licensing of MSCs is prolonged in IFN-γ-iECM, the T cell proliferation assay did not show a significant difference compared to the blank control. This is likely due to activated T cells in the assay releasing IFN-γ that stimulates the encapsulated MSCs, masking the effects of sustained licensing. Therefore, this experimental setup did not allow us to compare the functional effects of the systems and further investigation is warranted to determine the effects of prolonged licensing of MSCs by loading IFN-γ. In turn, these data proved that MSCs encapsulated in iECM are capable of inhibiting T cell proliferation in vitro and that loading IFN-γ in the matrices does not negatively impact T cell proliferation [36].

We propose short-term modulation of the local microenvironment at the gel site could be sufficient to re-program the systemic immune response. Our results are consistent with previous findings demonstrating that the effects of MSC transplantation in animal models typically exceed the half-life of the delivered cells. Intravenously delivered MSCs typically have a very short half-life of less than 24 hours, but still improved the acute response to sepsis over 90 hours [37]. Intraperitoneal delivery of MSCs reduced experimental colitis [38], even though cells are fully cleared by 3–7 days [39]. Additionally, we expect that hydrogel encapsulation will prolong the in vivo residence time of transplanted cells, because microfluidic-based encapsulation increased the residence time of intravenously delivered MSCs by an order of magnitude [40].

We report iECM hydrogels as a multifunctional platform to enhance the immunomodulatory properties of MSCs. A potential application of this new multifunctional system is to provide tunable control of immunomodulation of transplanted MSCs in experimental cell therapies for the treatment of chronic inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease, graft-versus-host disease or rheumatoid arthritis [41,42]. Multifunctional ECM could be an important tool to better control behavior of transplanted cells and potentially avoid the important adverse reactions and drug-resistance issues of the currently available treatments [43,44].

5. Conclusions

A bioinspired multifunctional system was developed that combined 3D biomimetic cell culture and sustained inflammatory licensing to enhance the immunomodulatory potential of hMSCs. While standard licensing of MSCs in vitro is transient, we find that a biomimetic artificial extracellular matrix of collagen, chemically-modified alginate and cytokine-loaded heparin-coated beads prolonged immunomodulatory licensing of hMSCs. 3D cell culture increased expression of immunomodulatory genes, and inclusion of heparin-coated beads prolonged the expression of immunomodulatory factors. Furthermore, IFN-γ-iECM encapsulated hMSCs suppressed T cell proliferation in vitro. Together, these findings suggest that sustained licensing in ECM hydrogels can be used to instruct MSC immunomodulatory behavior.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the projects SAF2017-82292-R (MINECO/AEI/FEDER, UE), ICTS “NANBIOSIS” (Drug Formulation Unit, U10), the National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01DE013033 (DM) and K08DE025292 (KV), and the support from the Basque Country Government (Grupos Consolidados, No ref: IT907-16). A. Gonzalez-Pujana thanks the Basque Government (Department of Education, Universities and Research) for the PhD grant (PRE_2018_2_0133). D.K.Y.Z. acknowledges support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings will be made available on request.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Gao F, Chiu SM, Motan DA, Zhang Z, Chen L, Ji HL, Tse HF, Fu QL, Lian Q, Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: current status and future prospects, Cell. Death Dis. 7 (2016) e2062 10.1038/cddis.2015.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Francois M, Romieu-Mourez R, Li M, Galipeau J, Human MSC suppression correlates with cytokine induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and bystander M2 macrophage differentiation, Mol. Ther. 20 (2012) 187–195. 10.1038/mt.2011.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ylostalo JH, Bartosh TJ, Coble K, Prockop DJ, Human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells cultured as spheroids are self-activated to produce prostaglandin E2 that directs stimulated macrophages into an antiinflammatory phenotype, Stem Cells. 30 (2012) 2283–2296. 10.1002/stem.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Benkhoucha M, Santiago-Raber ML, Schneiter G, Chofflon M, Funakoshi H, Nakamura T, Lalive PH, Hepatocyte growth factor inhibits CNS autoimmunity by inducing tolerogenic dendritic cells and CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107 (2010)6424–6429. 10.1073/pnas.0912437107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, Mingari MC, Moretta L, Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production: role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2, Blood. 111 (2008) 1327–1333. 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Terness P, Bauer TM, Rose L, Dufter C, Watzlik A, Simon H, Opelz G, Inhibition of allogeneic T cell proliferation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-expressing dendritic cells: mediation of suppression by tryptophan metabolites, J. Exp. Med. 196 (2002) 447–457. 10.1084/jem.20020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Corcione A, Benvenuto F, Ferretti E, Giunti D, Cappiello V, Cazzanti F, Risso M, Gualandi F, Mancardi GL, Pistoia V, Uccelli A, Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions, Blood. 107 (2006) 367–372. 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ferreira JR, Teixeira GQ, Santos SG, Barbosa MA, Almeida-Porada G, Goncalves RM, Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Secretome: Influencing Therapeutic Potential by Cellular Pre-conditioning, Front. Immunol. 9 (2018) 2837 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vizoso FJ, Eiro N, Cid S, Schneider J, Perez-Fernandez R, Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies in Regenerative Medicine, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (2017) 10.3390/ijms18091852. 10.3390/ijms18091852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gonzalez-Pujana A, Igartua M, Santos-Vizcaino E, Hernandez RM, Mesenchymal stromal cell based therapies for the treatment of immune disorders: recent milestones and future challenges, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 17 (2020) 189–200. 10.1080/17425247.2020.1714587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Krampera M, Cosmi L, Angeli R, Pasini A, Liotta F, Andreini A, Santarlasci V, Mazzinghi B, Pizzolo G, Vinante F, Romagnani P, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Annunziato F, Role for interferon-gamma in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, Stem Cells. 24 (2006) 386–398. 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Murphy N, Treacy O, Lynch K, Morcos M, Lohan P, Howard L, Fahy G, Griffin MD, Ryan AE, Ritter T, TNF-alpha/IL-1beta-licensed mesenchymal stromal cells promote corneal allograft survival via myeloid cell-mediated induction of Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells in the lung, FASEB J. (2019) fj201900047R. 10.1096/fj.201900047R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jin P, Zhao Y, Liu H, Chen J, Ren J, Jin J, Bedognetti D, Liu S, Wang E, Marincola F, Stroncek D, Interferon-gamma and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Polarize Bone Marrow Stromal Cells Uniformly to a Th1 Phenotype, Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 26345 10.1038/srep26345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bartosh TJ, Ylostalo JH, Mohammadipoor A, Bazhanov N, Coble K, Claypool K, Lee RH, Choi H, Prockop DJ, Aggregation of human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) into 3D spheroids enhances their antiinflammatory properties, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107 (2010) 13724–13729. 10.1073/pnas.1008117107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Petrenko Y, Sykova E, Kubinova S, The therapeutic potential of three-dimensional multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell spheroids, Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 8 (2017) 94–017-0558–6. 10.1186/s13287-017-0558-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zimmermann JA, Hettiaratchi MH, McDevitt TC, Enhanced Immunosuppression of T Cells by Sustained Presentation of Bioactive Interferon-gamma Within Three-Dimensional Mesenchymal Stem Cell Constructs, Stem Cells Transl. Med. 6 (2017) 223–237. 10.5966/sctm.2016-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vining KH, Stafford A, Mooney DJ, Sequential modes of crosslinking tune viscoelasticity of cell-instructive hydrogels, Biomaterials. 188 (2019) 187–197. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Popov C, Radic T, Haasters F, Prall WC, Aszodi A, Gullberg D, Schieker M, Docheva D, Integrins alpha2beta1 and alpha11beta1 regulate the survival of mesenchymal stem cells on collagen I, Cell. Death Dis. 2 (2011) e186 10.1038/cddis.2011.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Desai RM, Koshy ST, Hilderbrand SA, Mooney DJ, Joshi NS, Versatile click alginate hydrogels crosslinked via tetrazine-norbornene chemistry, Biomaterials. 50 (2015) 30–37. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Naji A, Eitoku M, Favier B, Deschaseaux F, Rouas-Freiss N, Suganuma N, Biological functions of mesenchymal stem cells and clinical implications, Cell Mol. Life Sci. (2019). 10.1007/s00018-019-03125-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Duffin R, O'Connor RA, Crittenden S, Forster T, Yu C, Zheng X, Smyth D, Robb CT, Rossi F, Skouras C, Tang S, Richards J, Pellicoro A, Weller RB, Breyer RM, Mole DJ, Iredale JP, Anderton SM, Narumiya S, Maizels RM, Ghazal P, Howie SE, Rossi AG, Yao C, Prostaglandin E(2) constrains systemic inflammation through an innate lymphoid cell-IL-22 axis, Science. 351 (2016) 1333–1338. 10.1126/science.aad9903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fan J, Tang X, Wang Q, Zhang Z, Wu S, Li W, Liu S, Yao G, Chen H, Sun L, Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate experimental autoimmune cholangitis through immunosuppression and cytoprotective function mediated by galectin-9, Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 9 (2018) 237–018-0979-x. 10.1186/s13287-018-0979-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lim JY, Im KI, Lee ES, Kim N, Nam YS, Jeon YW, Cho SG, Enhanced immunoregulation of mesenchymal stem cells by IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T cells in collagen-induced arthritis, Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 26851 10.1038/srep26851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mbongue JC, Nicholas DA, Torrez TW, Kim NS, Firek AF, Langridge WH, The Role of Indoleamine 2, 3-Dioxygenase in Immune Suppression and Autoimmunity, Vaccines (Basel). 3 (2015) 703–729. 10.3390/vaccines3030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ortiz LA, Dutreil M, Fattman C, Pandey AC, Torres G, Go K, Phinney DG, Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung injury, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 (2007) 11002–11007. 10.1073/pnas.0704421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gonzalez-Pujana A, Rementeria A, Blanco FJ, Igartua M, Pedraz JL, Santos-Vizcaino E, Hernandez RM, The role of osmolarity adjusting agents in the regulation of encapsulated cell behavior to provide a safer and more predictable delivery of therapeutics, Drug Deliv. 24 (2017) 1654–1666. 10.1080/10717544.2017.1391894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pourgholaminejad A, Aghdami N, Baharvand H, Moazzeni SM, The effect of pro-inflammatory cytokines on immunophenotype, differentiation capacity and immunomodulatory functions of human mesenchymal stem cells, Cytokine. 85 (2016) 51–60. 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Huebsch N, Arany PR, Mao AS, Shvartsman D, Ali OA, Bencherif SA, Rivera-Feliciano J, Mooney DJ, Harnessing traction-mediated manipulation of the cell/matrix interface to control stem-cell fate, Nat. Mater. 9 (2010) 518–526. 10.1038/nmat2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chaudhuri O, Gu L, Klumpers D, Darnell M, Bencherif SA, Weaver JC, Huebsch N, Lee HP, Lippens E, Duda GN, Mooney DJ, Hydrogels with tunable stress relaxation regulate stem cell fate and activity, Nat. Mater. 15 (2016) 326–334. 10.1038/nmat4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Saesen E, Sarrazin S, Laguri C, Sadir R, Maurin D, Thomas A, Imberty A, Lortat-Jacob H, Insights into the mechanism by which interferon-gamma basic amino acid clusters mediate protein binding to heparan sulfate, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 9384–9390. 10.1021/ja4000867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lortat-Jacob H, Baltzer F, Grimaud JA, Heparin decreases the blood clearance of interferon-gamma and increases its activity by limiting the processing of its carboxyl-terminal sequence, J. Biol. Chem. 271 (1996) 16139–16143. 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ungerer C, Quade-Lyssy P, Radeke HH, Henschler R, Konigs C, Kohl U, Seifried E, Schuttrumpf J, Galectin-9 is a suppressor of T and B cells and predicts the immune modulatory potential of mesenchymal stromal cell preparations, Stem Cells Dev. 23 (2014) 755–766. 10.1089/scd.2013.0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Guan Q, Li Y, Shpiruk T, Bhagwat S, Wall DA, Inducible indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 and programmed death ligand 1 expression as the potency marker for mesenchymal stromal cells, Cytotherapy. 20 (2018) 639–649. https://doi.org/S1465-3249(18)30038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Li H, Deng Y, Liang J, Huang F, Qiu W, Zhang M, Long Y, Hu X, Lu Z, Liu W, Zheng SG, Mesenchymal stromal cells attenuate multiple sclerosis via IDO-dependent increasing the suppressive proportion of CD5+ IL-10+ B cells, Am. J. Transl. Res. 11 (2019) 5673–5688. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bolten SN, Rinas U, Scheper T, Heparin: role in protein purification and substitution with animal-component free material, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102 (2018) 8647–8660. 10.1007/s00253-018-9263-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Reed JM, Branigan PJ, Bamezai A, Interferon gamma enhances clonal expansion and survival of CD4+ T cells, J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 28 (2008) 611–622. 10.1089/jir.2007.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nemeth K, Leelahavanichkul A, Yuen PS, Mayer B, Parmelee A, Doi K, Robey PG, Leelahavanichkul K, Koller BH, Brown JM, Hu X, Jelinek I, Star RA, Mezey E, Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E(2)-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production, Nat. Med. 15 (2009) 42–49. 10.1038/nm.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Castelo-Branco M, Soares IDP, Lopes DV, Buongusto F, Martinusso CA, do Rosario A Jr, Souza SAL, Gutfilen B, Fonseca LMB, Elia C, Madi K, Schanaider A, Rossi MID, Souza HSP, Intraperitoneal but Not Intravenous Cryopreserved Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Home to the Inflamed Colon and Ameliorate Experimental Colitis, PLOS ONE. 7 (2012) e33360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bazhanov N, Ylostalo JH, Bartosh TJ, Tiblow A, Mohammadipoor A, Foskett A, Prockop DJ, Intraperitoneally infused human mesenchymal stem cells form aggregates with mouse immune cells and attach to peritoneal organs, Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 7 (2016) 27–016-0284–5. 10.1186/s13287-016-0284-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mao AS, Özkale B, Shah NJ, Vining KH, Descombes T, Zhang L, Tringides CM, Wong S, Shin J, Scadden DT, Weitz DA, Mooney DJ, Programmable microencapsulation for enhanced mesenchymal stem cell persistence and immunomodulation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. (2019) 201819415 10.1073/pnas.1819415116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Liu CH, Abrams ND, Carrick DM, Chander P, Dwyer J, Hamlet MRJ, Macchiarini F, PrabhuDas M, Shen GL, Tandon P, Vedamony MM, Biomarkers of chronic inflammation in disease development and prevention: challenges and opportunities, Nat. Immunol. 18 (2017) 1175–1180. 10.1038/ni.3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Buckley CD, Barone F, Nayar S, Benezech C, Caamano J, Stromal cells in chronic inflammation and tertiary lymphoid organ formation, Annu. Rev. Immunol. 33 (2015) 715–745. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Fiorino G, Bonovas S, Cicerone C, Allocca M, Furfaro F, Correale C, Danese S, The safety of biological pharmacotherapy for the treatment of ulcerative colitis, Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 16 (2017) 437–443. 10.1080/14740338.2017.1298743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lightner AL, Stem Cell Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 8 (2017) e82 10.1038/ctg.2017.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.