Abstract

The increasing rate of incidence and prevalence of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) worldwide, combined with the morbidity associated with conventional surgical treatment has led to the development and use of alternative minimally invasive non-surgical treatments. Biopsy and pathology are used to guide BCC diagnosis and assess margins and subtypes, which then guide the decision and choice of surgical or non-surgical treatment. However, alternatively, a noninvasive optical approach based on combined reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging may be used. Optical imaging may be used to guide diagnosis and margin assessment at the bedside, and potentially facilitate non-surgical management, along with long-term monitoring of treatment response. Noninvasive imaging may also complement minimally invasive treatments and help further reduce morbidity. In this paper, we highlight the current state of an integrated RCM/OCT imaging approach for diagnosis and triage of BCCs, as well as for assessing margins, which therefore may be ultimately used for guiding therapy.

Keywords: basal cell carcinomas, invasive non-surgical treatments, reflectance confocal microscopy, optical coherence tomography

Introduction

Approximately 2.4 million new cases of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) are diagnosed every year in the U.S. and about another 800,000 in other regions of the world 1-3. BCCs occur most commonly in older (> 65 years) and in middle-aged people (40-65 years), but, recently its incidence has been increasing in younger people, too 4,5. Approximately 80-90% of the cases occur in the head-and-neck area, including 65% on the face, which includes in high-risk functional anatomical areas such as the nose, eyes, ears or mouth 6,7. Although mostly non-fatal, BCCs can cause large-scale anatomical destruction, resulting in morbidity, physical disfigurement, loss of function (breathing, hearing, swallowing and vision) and psychological trauma. Preserving quality of life - preserving tissue and anatomy, cosmesis and function, reducing morbidity and pain, minimizing collateral damage - is a key objective during treatment. BCCs are conventionally treated with either surgical excision with wide margin control or Mohs micrographic surgery with microscopic margin control 8,9. Both surgical treatments produce high cure rates 10,11. However, the increasing rates of incidence and prevalence of BCCs worldwide has led to the development and use of minimally invasive non-surgical treatments, which offer lower morbidity and improved quality of life. Non-surgical treatments include topical therapy (Imiquimod), photodynamic therapy, radiotherapy, and laser ablation and/or coagulation 12-17. Guiding the decision and choice of an appropriate minimally invasive therapy is dependent on determining BCC depth and subtype 18,19.

Low-risk non-aggressive shallow (depth < 400 µm) superficial and early nodular types of BCC are amenable to non-surgical treatments, whereas deeper (depth > 400 µm) nodular and high-risk micronodular, infiltrative and sclerosing subtypes require treatment with surgical excision or Mohs surgery. Current diagnosis, depth and subtyping are determined with biopsy followed by histopathological analysis. Instead of biopsy, alternatively, a noninvasive imaging approach may be used to guide diagnosis and determine depth and subtype. Noninvasive imaging may also complement minimally invasive treatments and help further reduce morbidity and preserve quality of life.

We investigated the use of a non-invasive optical imaging method, based on integrating reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) into a single instrument. Many studies have shown that both OCT and RCM imaging, when used individually and independently can noninvasively detect superficial and nodular BCCs with sensitivities and specificities in the range 80-95% and 70-90%, respectively 20-26. Since RCM provides cellular-level resolution, it can be used to accurately detect the morphological features of BCCs and provide high diagnostic accuracy. However, imaging depth is limited to ~200 µm, and therefore determination of margins is possible only for superficial tumors in the papillary dermis. On the other hand, OCT imaging reaches deeper, into the reticular dermis to depth of ~1.5 mm and can be used to detect deeper nodular, micronodular, infiltrative and sclerosing tumors and delineate deeper margins. Therefore, the combined use of RCM and OCT within the same instrument provides enhanced capabilities for skin cancer detection and especially for therapy guidance. Their sequential use on a specific lesion is not desirable since spatial co-registration of the images enables enhanced cancer detection and margins delineation. Furthermore, sequential use doubles the imaging time and thus the costs of the procedure. In addition, it requires the acquisition of two instruments, which are more expensive than a combined instrument. Our approach to integrate RCM and OCT within a single instrument was thus a logical step toward further advancing the translation and clinical use for diagnosis of BCC and margin delineation.

In this paper, we highlight the unique feature the integrated RCM/OCT instruments by summarizing the results of a preliminary patient study. In this study, an OCT/RCM instrument with a hand-held probe was tested for BCC diagnosis and delineation of deep and lateral margins. Based on spreading depth measurements, triage of BCCs into deeper aggressive high-risk or shallower non-aggressive low-risk types was possible.

Material and Methods

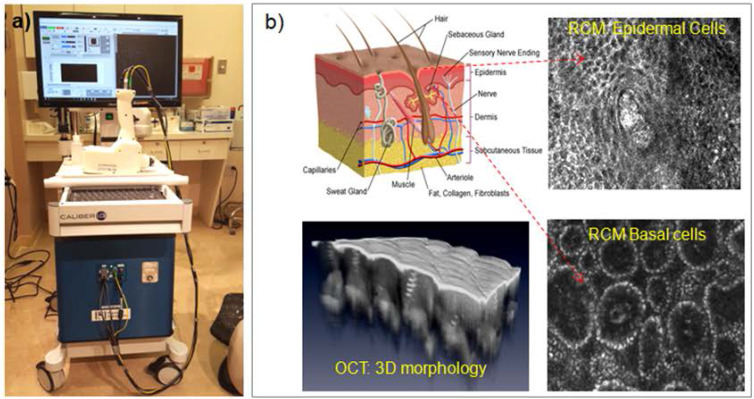

The integrated RCM-OCT imaging instrument was designed and engineered at Physical Sciences Inc. and clinically tested at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). A photograph of the RCM/OCT instrument and its imaging capabilities are shown in Figure 1 27. As observed, a hand-held probe is attached to an instrumentation wheeled cart through electrical and fiber optics cables. This probe, weighting approximately 3 lb, enables rapid collection of spatially co-registered RCM-OCT images, and thus informed therapy decision making. The contact with the patient skin is made through a sterilzable plastic window, which is gently pressed against skin. To avoid secular reflection from the skin, an index matching microscopy oil is used.

Figure 1.

(a) Photograph of the RCM-OCT instrument and hand-held probe; (b) Representative RCM and OCT images of the healthy skin.

In a pilot clinical study on 85 patients, 60 with lesions that were clinically suspicious (but not biopsied) for BCCs (n=60) and 25 with biopsy-proven BCCs, we correlated features of BCCs seen on RCM and OCT images with those seen in histopathology, calculated diagnostic accuracy and correlated depth predicted by OCT with histopathologically measured depth 28. Histology data were analyzed by a clinical histopathologist from MSKCC, while OCT/RCM data were analyzed by four readers, trained to interpret these images. The RCM/OCT readers were blind to histology results, as the RCM/OCT data was analyzed immediately after acquisition, while histology preparation and analysis took several more days.

RCM/OCT features of interest for BCC diagnosis used by other investigators in previous independent RCM and OCT studies were analyzed. These features are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Integrated RCM-OCT features for BCC diagnosis

| RCM Features | OCT Features |

|---|---|

| Epidermal streaming | Hyporeflective or gray structures attached to the dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ) |

| Tumor nests | Disruption of the DEJ |

| Cordlike structures | Hyporeflective or gray ovoid structures in the dermis |

| Nuclear palisading at tumor edge | Dark peritumoral rim (clefting) |

| Dark peritumoral rim (clefting) | Hyperreflective peritumoral stroma |

| Stroma with plump cells and bright dots | Hypo- and hyper-reflective streaks in dermis |

| Horizontal vessels | Branched vessels |

Results and Discussion

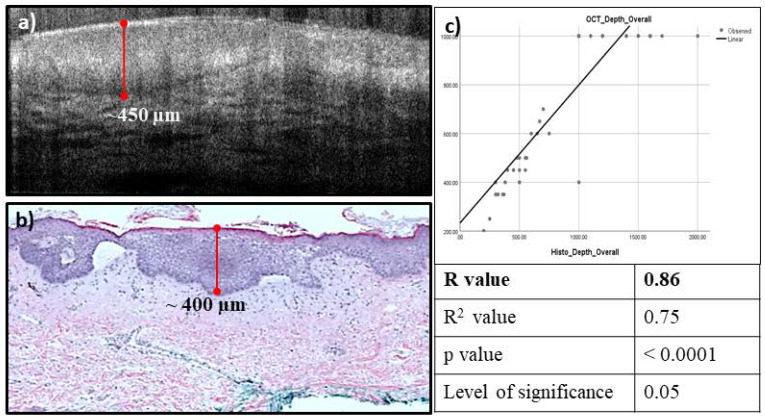

The main RCM/OCT features used in BCC diagnosis, such as small tumors within extending from the base of the epidermis; small and large tumor nests; tumor in dermis; dark silhouettes; dilated blood vessels; horn cysts; and bright peritumoral stroma were analyzed. Additional features such as necrosis and intratumoral mucin pools were correlated on OCT and histology. Higher sensitivity and negative predictive value (100%) and comparable specificity (48% vs 56% on RCM) and positive predictive value (82.19 vs 84.59 % on RCM) were observed for integrated RCM/OCT imaging for diagnosis of all lesions (n=85). Relatively higher specificity (94.1%) and positive predictive value (75%) were observed in the clinically suspicious lesions (n=60). High correlation was observed (R=0.86) between the OCT-predicted depth and histopathologically measured depth (see example in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

High Correlation observed between the estimated OCT depth (a), and the measured histopathology depth (b), the correlation coefficient was found to be 0.86 (c).

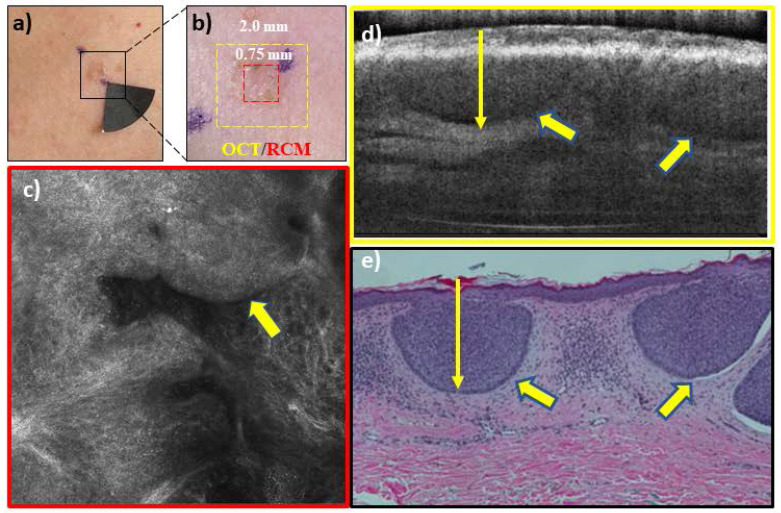

In addition to diagnosis and depth assessment, we are investigating the complementary capabilities of integrated RCM-OCT imaging for identifying aggressive and non-aggressive subtypes. This is crucial, as management of BCCs depends on both depth and subtype. Non-aggressive subtypes (Figure 3), which make up about 60% of all BCCs, can be treated with non-surgical approaches, while aggressive subtypes (Figure 4) require surgical management and depth assessment. Our latest studies, in progress, show preliminary promise of RCM-OCT for stratifying aggressive and non-aggressive BCCs. The additional capability for stratifying subtypes may help in lesion triage into surgical and non-surgical treatments. Additionally, RCM/OCT may also enable non-invasive monitoring of non-surgical treatments (in the absence of conventional pathology) to ensure tumor clearance. RCM/OCT imaging may be prospectively used to comprehensively diagnose suspicious lesions, determine aggressiveness and depths, triage for treatment and help in monitoring response to treatment.

Figure 3.

RCM-OCT imaging of a lesion on the chest of a 42 year woman which was clinically (a), and dermoscopically (b) suspicious for a basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The RCM image (c) shows tumor nests (yellow arrow) extending from the epidermis into superficial dermis with peripheral palisading and dark peritumoral rim- features diagnostic for BCC. The OCT image (d) shows a hyporeflective tumor nest (yellow arrow) with a dark peritumoral rim within the same spatial area. Based on the overall imaging, the lesion was called a superficial BCC with a depth of ~400 µm which can be treated with noninvasive approaches or superficial shave biopsy. Histopathology (e) confirmed the presence of superficial BCC with a depth of ~350 µm.

Figure 4.

RCM-OCT imaging of a lesion on left cheek of an 83 year old woman which was clinically (a), and dermoscopically (b) suspected to be a basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The RCM images (c) shows large and small tumor nests (yellow arrows) in upper dermis with peripheral palisading and dark peritumoral rim. The OCT image (d) shows several elongated hyporeflective tumor nests even in the deeper dermis. Based on the overall imaging, the lesion was called a noduloinfiltrative BCC with a depth of >1000 um which is treated with surgical options. Histopathology (e) confirmed the presence of nodulo-infiltrative BCC with a depth of >1000 µm.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggest that an integrated RCM/OCT noninvasive imaging approach shows promise for guiding BCC diagnosis and even more important for providing reliable margin and depth assessment. Recent work also indicates RCM/OCT promise for determining BCC subtype. However, larger prospective clinical trials are needed to confirm our initial findings and determine whether RCM/OCT imaging may potentially serve as an adjunct to biopsy and histopathology, and thus to guide therapy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants 1 R44 CA240040, R01EB020029 and by MSKCC's Cancer Center grant P30CA008748.

References

- 1.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, Coldiron BM. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(10):1081–6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stern RS. Prevalence of a history of skin cancer in 2007: results of an incidence-based model. Arch. Dermatol. 2010;146(3):279–82. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guy GP, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S, 2002-2006 and 2007-2011. Am. J. Prev Med. 2015;48(2):183–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher RP, Ma B, McLean DI. et al. Trends in basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma of the skin from 1973 through 1987. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:413–9. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray DT, Suman VJ, Su WP, Clay RP, Harmsen WS, Roenigk RK. Trends in the population-based incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin first diagnosed between 1984 and 1992. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:735–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. British Journal of Dermatol. 2002;147(1):41–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bastiaens MT, Hoefnagel JJ, Bruijn JA, Westendorp RGJ, Vermeer BJ, Bavinck JNB. Differences in age, site distribution, and sex between nodular and superficial basal cell carcinomas indicate different types of tumors. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1998;110(6):880–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viola KV. et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment in the Medicare population. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(4):473–7. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wetzig T, Woitek M, Eichhorn K, Simon JC, Paasch U. Surgical excision of basal cell carcinoma with complete margin control: outcome at 5-years follow-up. Dermatology. 2010;220:363–9. doi: 10.1159/000300116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimyai-Asadi A, Alam M, Goldberg LH, Peterson SR, Silapunt S, Jih MH. Efficacy of narrow-margin excision of well-demarcated primary facial basal cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:464–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snow SN, Mikhail GR. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. 2nd ed. Madison, Wisc: University of Wisconsin Press. 2005.

- 12.Amini S, Viera MH, Valins W. et al. Nonsurgical Innovations in the Treatment of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3(6):20–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choudhary S, Tang L, Elsaie ML. et al. Lasers in the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol. Surg. 2011;37(4):409–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smucler R, Vlk M. Combination of Er∶YAG laser and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of nodular basal cell carcinoma. Lasers Surg Med. 2008;40(2):153–8. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smucler R, Kriz M, Lippert J, Vlk M. Ultrasound guided ablative-laser assisted photodynamic therapy of basal cell carcinoma (US-aL-PDT) Photomed Laser Surg. 2012;30(4):200–5. doi: 10.1089/pho.2011.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams HC. et al. Surgery Versus 5% Imiquimod for Nodular and Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma: 5-Year Results of the SINS Randomized Controlled Trial. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(3):614–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahner JD, Bordeaux JS. Non-melanoma skin cancers: photodynamic therapy, cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, diclofenac, or what? Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(6):792–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willardson HB, Lombardo J, Raines M. et al. Predictive value of basal cell carcinoma biopsies with negative margin: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(1):42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnelbelen AM, Gardner JM, Shalin SC. Margin status in shave biopsies of nonmelanoma skin cancers: Is it worth reporting? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(7):678–81. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0313-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guitera P, Menzies SW, Longo C. et al. In vivo confocal microscopy for diagnosis of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma using a two-step method: analysis of 710 consecutive clinically equivocal cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(10):2386–94. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinz T, Ehler Lin-K, Hornung T, Voth H, Fortmeier I, Maier T, Höller T, Schmid-Wendtner MH. Preoperative Characterization of Basal Cell Carcinoma Comparing Tumour Thickness Measurement by Optical Coherence Tomography, 20-MHz Ultrasound and Histopathology. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:132–7. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olmedo JM, Warschaw KE, Schmitt JM, Swanson DL. Correlation of Thickness of Basal Cell Carcinoma by Optical Coherence Tomography In vivo and Routine Histologic Findings: A Pilot Study. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:421–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, Halpern AC, Nehal KS. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(1):7–19. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Braunmühl T, Hartmann D, Tietze JK, Cekovic D, Kunte C, Ruzicka T, Berking C, Sattler EC. Morphologic features of basal cell carcinoma using the en-face mode in frequency domain optical coherence tomography. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(11):1919–25. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boone M, Suppa M, Miyamoto M, Marneffe A, Jemec G, Del Marmol V. In vivo assessment of optical properties of basal cell carcinoma and differentiation of BCC subtypes by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Biomed Opt Express. 2016;7(6):2269–84. doi: 10.1364/BOE.7.002269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avanaki M, Hojjatoleslami A, Sira M, Schofield J B, Jones C, Podoleanu A Gh. Investigation of basal cell carcinoma using dynamic focus optical coherence tomography. Appliea Opt. 2013;52(10):2116–24. doi: 10.1364/AO.52.002116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iftimia N, Yélamos O. Chen CJ, Maguluri G, Cordova MA, Sahu A, Park J, Fox W, Alessi-Fox C, Rajadhyaksha M. Handheld Optical Coherence Tomography-Reflectance Confocal Microscopy Probe for Detection of Basal Cell Carcinoma and Delineation of Margins. J Biomed Opt. 2017;22(7):76006. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.22.7.076006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahu A, Yélamos O, Iftimia N, Cordova M, Alessi-Fox C, Gill M, Maguluri G, Dusza SW, Navarrete-Dechent C, González S, Rossi AM, Marghoob AA, Rajadhyaksha M, Chen CJ. Evaluation of a Combined Reflectance Confocal Microscopy-Optical Coherence Tomography Device for Detection and Depth Assessment of Basal Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(10):1175–83. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]