Abstract

Aims/Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a specific risk factor for intracranial atherosclerosis. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus, especially uncontrolled glycemia, and intracranial plaque characteristics using high‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging.

Materials and Methods

A total of 263 patients (182 men; mean age 62.6 ± 11.5 years) with intracranial atherosclerotic plaques detected on high‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging from December 2017 to March 2019 were included in this study. Patients were divided into different groups: (i) patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus; (ii) diabetes patients with uncontrolled glycemia (glycated hemoglobin level ≥7.0%) and controlled glycemia; and (iii), diabetes patients with diabetes duration of <5, 5–10 and >10 years. Comparisons of plaque features between groups were made, respectively.

Results

Type 2 diabetes mellitus was diagnosed in 118 patients (44.9%). Diabetes patients had a significantly greater prevalence of enhanced plaque, greater maximum plaque length, maximum wall thickness and more severe luminal stenosis than non‐diabetes patients. Compared with diabetes patients with controlled glycemia, those with uncontrolled glycemia had a significantly greater prevalence of enhanced plaque and greater maximum plaque length (all P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in plaque features among patients with different durations of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Uncontrolled glycemia was an independent factor for plaque enhancement after adjustment for potential confounding factors (odds ratio 5.690; 95% confidence interval 1.748–18.526; P = 0.004).

Conclusions

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is closely related to intracranial plaque enhancement and burden. Recently uncontrolled glycemia might play an important role in the development of enhanced plaque.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, High‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging, Intracranial atherosclerosis

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is closely related to intracranial plaque enhancement and burden, and poor glycemic control was an independent factor for intracranial plaque enhancement. This suggests that continuous exposure to hyperglycemia might play an important role in the development of intracranial vulnerable plaque.

Introduction

Intracranial atherosclerotic disease has been regarded as a main cause of ischemic stroke in Asian populations1, 2. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a well‐known risk factor for atherosclerosis3, 4, with an increase by two‐ to threefold in risk for cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, 65% of deaths in populations with type 2 diabetes mellitus are related to cardio‐ and cerebrovascular diseases5, 6.

Conventional magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and computed tomography angiography can be used to assess intracranial arterial stenosis. However, these imaging methods have not been able to show intracranial arterial plaque features, such as distribution, composition and its vulnerability7. High‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging (HR‐MRI) has been increasingly applied to evaluate intracranial atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability in recent years. Inflammation that increases plaque instability can be detected on HR‐MRI using gadolinium‐containing contrast agents8, 9. The degree of plaque enhancement is recognized to reflect the level of inflammatory activity because of its close relationship with increased neovascularity and endothelial permeability within the plaque, which is closely related to recent ischemic stroke10.

Plaque vulnerability might be affected by many risk factors. Intracranial atherosclerosis has different features from extracranial atherosclerosis in risk factors and pathogenesis11. The former is more influenced by type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome, but less influenced by hypercholesterolemia as compared with the latter12. Previous research has shown that type 2 diabetes mellitus is related to a particular atherosclerotic pattern, such as lipid core expansion, intraplaque hemorrhage and neovascularisation13, 14. This suggests that type 2 diabetes mellitus might play an important part in the development of vulnerable plaque. However, there are few studies about the influences of type 2 diabetes mellitus, especially poor glycemic control on intracranial plaque characteristics detected on HR‐MRI.

The present study aimed to investigate the association between type 2 diabetes mellitus, especially recently uncontrolled glycemia and intracranial plaque characteristics using HR‐MRI.

Methods

Study population

From December 2017 to March 2019, patients who had symptoms (ischemic events or dizziness) or intracranial artery stenosis detected by MRA or computed tomography angiography received HR‐MRI scanning. The patients who had intracranial atherosclerotic plaques identified on HR‐MRI were enrolled in this study. The exclusion criteria included: (i) type 1 diabetes; (ii) other intracranial arterial diseases, such as artery dissection, moyamoya disease or vasculitis; (iii) implementation of stenting and/or angioplasty; (iv) total vessel occlusion; (v) contraindication to MRI examination; and (vi) claustrophobia. Patients were divided into different groups, respectively: (i) patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus; (ii) diabetes patients with uncontrolled and controlled glycemia; and (iii) diabetes patients with the duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus <5, 5–10 and >10 years. We made an initial assessment on the history and the duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus from patients or caregivers. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was defined as ≥200 mg/dL of casual plasma glucose, ≥126 mg/dL of fasting plasma glucose, ≥200 mg/dL of 2‐h plasma glucose or having a history of diabetes and taking hypoglycemic medication15. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was routinely tested in all the enrolled patients. Poor glycemic control was defined as HbA1c level ≥7.0%. We collected other information from the clinical records, including age, sex, body mass index, history of smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and coronary heart disease. The levels for total cholesterol, triglyceride, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol and low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol were recorded. HbA1c was checked using a G8 Hemoglobin Testing System (TOSHO, Tokyo, Japan). Plasma glucose, total cholesterol, triglyceride, high‐density lipoprotein and low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were assayed by automatic enzymatic methods. This study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Hospital, Beijing, China, and we obtained written informed consent from all patients.

MRI protocol

All the MR examinations were completed by using a 3.0‐T MR scanner (Achieva; Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) with a 16‐channel NV coil. The sequences of HR‐MRI included three‐dimensional time of flight MRA and pre‐ and post‐contrast T1W imaging (VISTA). The parameters are as follows. Time of flight MRA: repetition time = 25 ms, echo time = 3.45 ms, field of view = 180 × 180 mm and acquired resolution = 0.55 × 0.55 × 1.1 mm; and T1W imaging: repetition time = 800 ms, echo time = 18 ms, field of view = 200 × 180 × 40mm and acquired resolution = 0.6 × 0.6 × 0.6 mm. Gadoteric acid meglumine (Dotarem; Guerbet, Aulnay‐sous‐Bois, France) was intravenously injected (0.1 mmol/kg of bodyweight). T1W imaging was repeated 5 min after injection.

Imaging analysis

The pre‐ and post‐contrast images were reconstructed at the location of wall thickening perpendicular to the direction of blood flow using picture archiving and communication system software. Images were reviewed by two neuroradiologists with >11 years of experience. The readers were blinded to clinical information. The three‐point scale from poor (image quality [IQ] = 1) to good (IQ = 3) was used to evaluate the IQ16. Patients with poor IQ were excluded from imaging analysis. Luminal stenosis, maximum plaque length and maximum wall thickness were measured on the reconstructed post‐contrast images at the site of the most stenotic lesion or the most apparent wall thickening for each patient. Then we calculated the ratio of maximum plaque length to maximum wall thickness. The readers determined the presence of plaque enhancement. Plaque enhancement was considered if it presented apparent enhancement that was similar to pituitary enhancement. A standardized method was applied to measure luminal stenosis17. We mainly analyzed intracranial atherosclerotic lesions of the larger diseased arteries10, because intracranial arteries were smaller. All disagreements were settled by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described in percentages, and continuous variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons were made between two groups by using the χ2‐test or independent samples t‐test, as appropriate. Patients were classified by the duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus, and differences were tested with the Kruskal–Wallis test or one‐way analysis of variance (anova), as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression was further used to evaluate the relationship between uncontrolled glycemia and intracranial plaque enhancement. Interreader agreements of identification of plaque enhancement and measurements of plaque burden were assessed using the Cohen’s kappa analysis and the Pearson correlation analysis, respectively. All statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The differences were considered statistically significant if P‐value <0.05 (2‐tailed).

Results

Originally, 285 patients who had intracranial plaque were included in this study. Of the 285 patients, 22 were excluded for the following reasons: IQ in four patients was poor; eight patients had complete vessel occlusion; and 10 patients had received operation of stenting and/or angioplasty before HR‐MRI examination. Finally, a total of 263 patients (182 men; mean age 62.6 ± 11.5 years) were enrolled in this study. The characteristics of the population in this study are summarized in Table 1. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was found in 118 patients (44.9%). Of the 118 diabetes patients, 71 (60.2%) had poor glycemic control. The duration of diabetes among the 118 diabetes patients was as follows: <5 years 36 patients (30.5%), 5–10 years 32 patients (27.1%) and >10 years 50 patients (42.4%).

Table 1.

Clinical and intracranial plaque characteristics of study population and comparison between diabetes and non‐diabetes patients

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | P‐value † | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 263) | Non‐diabetes patients (n = 145) | Diabetes patients (n = 118) | ||

| Age (years) | 62.6 ± 11.5 | 61.5 ± 11.9 | 63.8 ± 11.0 | 0.108 |

| Sex, male (%) | 182 (69.2%) | 100 (69.0%) | 82 (69.5%) | 0.927 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 ± 3.3 | 25.8 ± 3.3 | 25.6 ± 3.3 | 0.542 |

| Past medical history | ||||

| Smoking, n (%) | 105 (39.9%) | 61 (42.1%) | 44 (37.3%) | 0.431 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 207 (78.7%) | 107 (73.8%) | 100 (84.7%) | 0.031 |

| Hyperlipemia, n (%) | 181 (68.8%) | 103 (71.0%) | 78 (66.1%) | 0.390 |

| CHD, n (%) | 49 (18.6%) | 21 (14.5%) | 28 (23.7%) | 0.055 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL ‡ ) | 83.2 ± 36.1 | 85.2 ± 39.8 | 80.8 ± 31.2 | 0.320 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL ‡ ) | 39.1 ± 9.8 | 40.1 ± 9.5 | 37.8 ± 10.1 | 0.059 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL ‡ ) | 137.5 ± 41.0 | 136.0 ± 41.0 | 139.3 ± 41.1 | 0.521 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL § ) | 135.1 ± 76.1 | 128.5 ± 56.9 | 143.1 ± 94.2 | 0.142 |

| Plaque characteristics | ||||

| Presence of plaque enhancement, n (%) | 188 (71.5%) | 89 (61.4%) | 99 (83.9%) | <0.001 |

| Maximum plaque length (mm) | 6.0 ± 3.5 | 5.3 ± 3.0 | 6.9 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Maximum wall thickness (mm) | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 0.004 |

| Ratio of maximum length to thickness | 3.9 ± 2.1 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 4.1 ± 2.3 | 0.148 |

| Luminal stenosis (%) | 51.9 ± 30.8 | 43.8 ± 30.9 | 61.9 ± 27.8 | <0.001 |

For differences between diabetes patients and non‐diabetes patients. ‡To convert to the International System of Units (mmol/L), multiply by 0.0259. §To convert to International System of Units (mmol/L), multiply by 0.0113. BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein.

Comparison of clinical and intracranial plaque characteristics between diabetes patients and non‐diabetes patients

Compared with non‐diabetes patients, diabetes patients had a significantly greater prevalence of hypertension (84.7 vs 73.8%, P = 0.031) and enhanced plaque (83.9 vs 61.4%, P < 0.001), greater maximum plaque length (6.9 ± 3.8 vs 5.3 ± 3.0 mm, P < 0.001), maximum wall thickness (2.0 ± 1.3 vs 1.6 ± 0.8 mm, P = 0.004), and more severe luminal stenosis (61.9 ± 27.8% vs 43.8 ± 30.9%, P < 0.001). The results did not show significant differences in other variables between the diabetes patients and non‐diabetes patients (all P > 0.05; Table 1). Two typical cases with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus were presented (Figures 1,2).

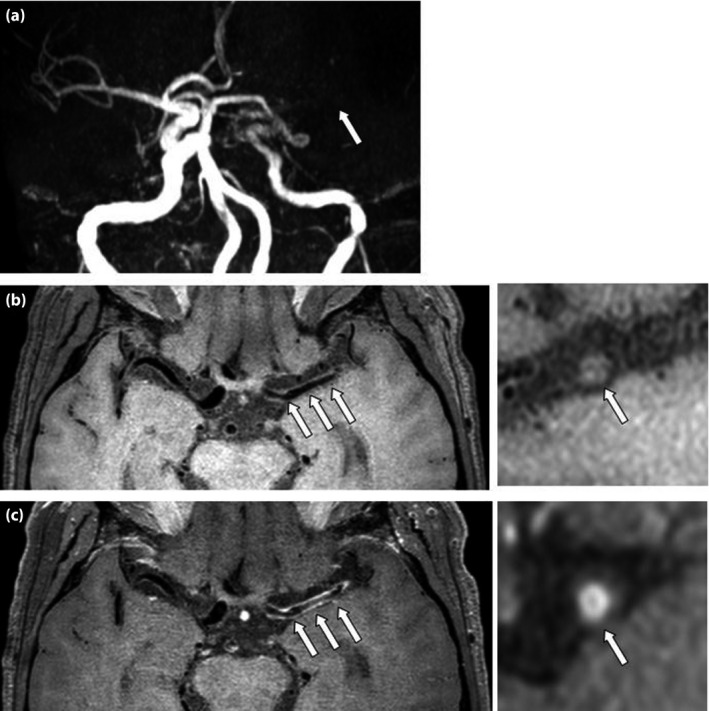

Figure 1.

Patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus for 15 years and poor glycemic control. (a) Time of flight magnetic resonance angiography shows severe stenosis and occlusion in the M1 segment of the left middle cerebral artery (arrow). (b) Pre‐ and (c) post‐contrast axial T1W (left) show diffuse wall thickening correspondingly (arrow). Reconstructions (right) show a large atherosclerotic plaque (arrow) with enhancement.

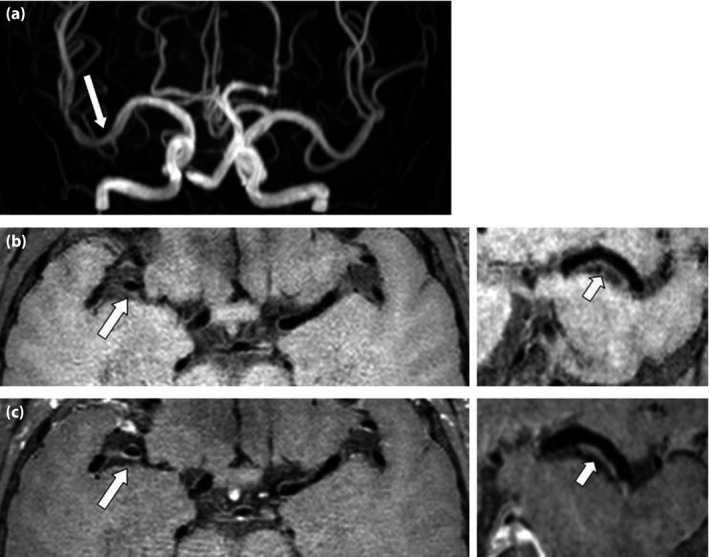

Figure 2.

Patient without type 2 diabetes mellitus. (a) Time of flight magnetic resonance angiography shows mild stenosis in the M1 segment of the right middle cerebral artery (arrow). (b) Pre‐ and (c) post‐contrast axial T1W images (left) show mild wall thickening correspondingly (arrow). Reconstructions (right) show a small plaque (arrow) without enhancement.

Comparisons of intracranial plaque characteristics between diabetes patients with uncontrolled and controlled glycemia, and patients with different duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Patients with uncontrolled glycemia had a significantly greater prevalence of enhanced plaque (91.5 vs 72.3%, P = 0.005) and greater maximum plaque length (7.5 ± 4.2 vs 6.1 ± 2.8 mm, P = 0.033) than patients with controlled glycemia. No significant differences were found in other plaque characteristics between patients with uncontrolled and controlled glycemia (all P > 0.05; Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences in all of the plaque characteristics among the patients with different duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus (all P > 0.05; Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of intracranial plaque characteristics between diabetes patients with uncontrolled and controlled glycemia, and patients with different durations of type 2 diabetes mellitus

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | P‐value | Mean ± SD or n (%) | P‐value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with controlled glycemia (n = 47) | Patients with uncontrolled glycemia (n = 71) | Duration <5 years (n = 36) | Duration 5–10 years, (n = 32) | Duration >10 years (n = 50) | |||

| Presence of plaque enhancement, n (%) | 34 (72.3%) | 65 (91.5%) | 0.005 | 33 (91.7%) | 26 (81.3%) | 40 (80.0%) | 0.311 |

| Maximum plaque length (mm) | 6.1 ± 2.8 | 7.5 ± 4.2 | 0.033 | 6.3 ± 3.3 | 6.3 ± 2.8 | 7.8 ± 4.4 | 0.117 |

| Maximum wall thickness (mm) | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 0.958 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 2.0 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 0.216 |

| Ratio of maximum length to thickness | 3.8 ± 1.8 | 4.2 ± 2.5 | 0.264 | 4.0 ± 1.7 | 3.7 ± 2.0 | 4.3 ± 2.8 | 0.527 |

| Luminal stenosis (%) | 56.7 ± 26.7 | 65.4 ± 28.1 | 0.098 | 60.2 ± 28.5 | 59.8 ± 28.5 | 64.5 ± 27.2 | 0.696 |

Association between uncontrolled glycemia and intracranial plaque enhancement

Uncontrolled glycemia had a significant association with intracranial plaque enhancement in unadjusted univariate analysis (odds ratio [OR] 6.335, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.608–15.387; P < 0.001). Uncontrolled glycemia was an independent factor for intracranial plaque enhancement after adjustment for potential confounding factors, such as age, sex, body mass index, smoking, hypertension, high‐density lipoprotein, low‐density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, triglyceride, duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus, luminal stenosis, maximum plaque length and maximum wall thickness (OR 5.690, 95% CI 1.748–18.526; P = 0.004; Table 3). There proved to be no collinearity of the covariates, verified by the collinearity diagnosis.

Table 3.

Association between uncontrolled glycemia and intracranial plaque enhancement

| Univariate regression | Multivariate regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P‐value | OR | 95% CI | P‐value | |

| Uncontrolled glycemia | 6.335 | 2.608–15.387 | <0.001 | 5.690 | 1.748–18.526 | 0.004 |

Multivariate logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking, hypertension, high‐density lipoprotein, low‐density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, triglyceride, duration of diabetes mellitus, luminal stenosis, maximum plaque length, and maximum wall thickness. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

MRI measurement reproducibility

Interreader agreement for determining plaque enhancement was excellent (kappa value 0.877; 95% CI 0.774, 0.951). The plaque burden was also found to be in agreement between both readers, because the Pearson correlation analysis presented a significant and positive correlation between independent measurements (r = 0.910, P < 0.001 between maximum plaque length measurements, r = 0.803, P < 0.001 between maximum wall thickness measurements and r = 0.977, P < 0.001 between luminal stenosis measurements).

Discussion

The present study investigated the relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus, especially recently uncontrolled glycemia, and intracranial plaque characteristics using HR‐MRI. We found that type 2 diabetes mellitus had a strong association with intracranial plaque enhancement and burden, and uncontrolled glycemia was an independent factor for intracranial plaque enhancement. The present findings suggest that type 2 diabetes mellitus is closely related to the severity of intracranial atherosclerotic disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, especially poor glycemic control, might play an important part in the development of enhanced plaque.

In this study, type 2 diabetes mellitus was strongly associated with intracranial plaque burden. Continuous exposure to hyperglycemia, oxidative stress and increased systemic inflammation factors might induce many changes in the vascular that might accelerate atherosclerosis18, 19. Compared with the healthy control group, the carotid intima‐media thickness values of diabetes patients were significantly higher20. Diabetes patients showed a greater percent atheroma volume and total atheroma volume in coronary atherosclerosis19. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is independently related to a greater degree of intracranial atherosclerosis and a higher number of involved vessels21. Most of the previous studies evaluated the severity of intracranial atherosclerosis with MRA by the pattern of intracranial stenosis and the number of vessels with significant stenosis22. In the present study, instead of using MRA or CTA to assess the severity of intracranial atherosclerosis, we used HR‐MRI to evaluated intracranial plaque burden and stability more directly and accurately, and studied its relationship with type 2 diabetes mellitus, which has seldom been reported.

With this study, we also found type 2 diabetes mellitus was strongly associated with intracranial plaque enhancement. It has been widely accepted that the plaque vulnerability, rather than lumen stenosis, plays an important role in ischemic stroke pathogenesis. Several studies have reported the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus on coronary and carotid plaque vulnerability. It was shown that type 2 diabetes mellitus was associated with carotid vulnerable plaque features23. A greater prevalence of vulnerable plaque was found in coronary specimens in diabetes patients than in non‐diabetes patients24. We found that type 2 diabetes mellitus had a close relationship with intracranial plaque enhancement on HR‐MRI. These findings might provide evidence for the studies on the mechanism and management of intracranial plaque vulnerability.

In the present study, the most interesting and important finding was that poor glycemic control was significantly correlated to intracranial plaque enhancement. Some studies have found that type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with poor glycemic control have a higher content of coronary vulnerable plaque detected on multidetector‐row computed tomography than those with good glycemic control25. Glycemic level is closely related to carotid atherosclerosis shown by luminal stenosis and intima‐media thickness26. Recently, it was reported that uncontrolled glycemia in diabetes patients is related to the severity of intracranial atherosclerosis evaluated using MRA22. So far, there are few studies on the relationship between uncontrolled glycemia and intracranial plaque vulnerability. The present study showed a strong relationship between uncontrolled glycemia and intracranial plaque enhancement, which indicates that poor glycemic control might play an important part in the development of intracranial plaque enhancement.

Surprisingly, the duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus was not significantly associated with intracranial plaque enhancement or plaque burden. Compared with patients who had type 2 diabetes mellitus for <5 years, carotid plaque vulnerability and the intima‐media thickness values of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus for >10 years were obviously higher20. A retrospective study showed that the prevalence of peripheral arterial and coronary atherosclerosis significantly increased with the duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus27. The result from the present study could be explained as follows: (i) some participants did not know the exact duration of their type 2 diabetes mellitus; (ii) we did not assess all the intracranial artery lesions, just the most serious lesion for each patient; and (iii) there is a possibility that the role of the duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus is less important for intracranial atherosclerosis than it is for the extracranial arteries. A similar finding was reported that the duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus was not significantly associated with the severity of intracranial atherosclerosis22.

The present study had some limitations. First, this was a cross‐sectional study. Prospective studies are required to determine whether the duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus and glycemic control are in close relationship to intracranial plaque enhancement and plaque burden in future. Second, HbA1c was used to reflect recent glycemic control. Future studies are warranted to study the impact of glycemic excursions on atherosclerotic plaque features. Third, the duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus was based on the memory of the patient or caregiver. This might cause information biases. Finally, histological verification was not obtained in the present findings, because it is difficult to obtain specimens of intracranial vessels.

In conclusion, type 2 diabetes mellitus is closely associated with intracranial plaque enhancement and burden, and poor glycemic control was an independent indicator for intracranial plaque enhancement. This suggests that continuous exposure to hyperglycemia might play an important role in the development of plaque vulnerability.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Meixia Shang of Department of Medical Statistics, Peking University First Hospital, for her technical expertise.

J Diabetes Investig 2020; 11: 1278–1284

References

- 1. Wong K, Huang Y, Gao S, et al Intracranial stenosis in Chinese patients with acute stroke. Neurology 1998; 50: 812–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu L‐H, Caplan L, Kwan E, et al Racial differences in ischemic cerebrovascular disease: clinical and magnetic resonance angiographic correlations of white and Asian patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 1996; 6: 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moreno PR, Fuster V. New aspects in the pathogenesis of diabetic atherothrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44: 2293–2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Idris I, Thomson GA, Sharma JC. Diabetes mellitus and stroke. Int J Clin Pract 2006; 60: 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burchfiel CM, Curb JD, Rodriguez BL, et al Glucose intolerance and 22‐year stroke incidence: the Honolulu Heart Program. Stroke 1994; 25: 951–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Folsom AR, Rasmussen ML, Chambless LE, et al Prospective associations of fasting insulin, body fat distribution, and diabetes with risk of ischemic stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 1077–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holmstedt CA, Turan TN, Chimowitz MI. Atherosclerotic intracranial arterial stenosis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 1106–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kerwin WS, Oikawa M, Yuan C, et al MR imaging of adventitial vasa vasorum in carotid atherosclerosis. Magn Reson Med 2008; 59: 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ibrahim T, Makowski MR, Jankauskas A, et al Serial contrast‐enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates regression of hyperenhancement within the coronary artery wall in patients after acute myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2009; 2: 580–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang J, Jiao S, Zhao X, et al Characteristics of patients with enhancing intracranial atherosclerosis and association between plaque enhancement and recent cerebrovascular ischemic events: a high‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. Acta Radiologica 2019; 60: 1301–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim JS, Nah H‐W, Park SM, et al Risk factors and stroke mechanisms in atherosclerotic stroke intracranial compared with extracranial and anterior compared with posterior circulation disease. Stroke 2012; 43: 3313–3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. D’Armiento FP, Bianchi A, de Nigris F, et al Age‐related effects on atherogenesis and scavenger enzymes of intracranial and extracranial arteries in men without classic risk factors for atherosclerosis. Stroke 2001; 32: 2472–2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Henry RM, Kostense PJ, Dekker JM, et al Carotid Arterial Remodeling: a maladaptive phenomenon in type 2 diabetes but not in impaired glucose metabolism: the Hoorn Study. Stroke 2004; 35: 671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luscher TF, Creager MA, Beckman JA, et al Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: Part II. Circulation 2003; 108: 1655–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. American Diabetes Association . 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: S13–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ryu CW, Jahng GH, Kim EJ, et al High resolution wall and lumen MRI of the middle cerebral arteries at 3 tesla. Cerebrovasc Dis 2009; 27: 433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chimowitz MI, Kokkinos J, Strong J, et al The Warfarin‐Aspirin symptomatic intracranial disease study. Neurology 1995; 45: 1488–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aronson D, Rayfield EJ. How hyperglycemia promotes atherosclerosis: molecular mechanisms. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2002; 1: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nicholls SJ, Tuzcu EM, Kalidindi S, et al Effect of diabetes on progression of coronary atherosclerosis and arterial remodeling: a pooled analysis of 5 intravascular ultrasound trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52: 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen W, Tian T, Wang S, et al Characteristics of carotid atherosclerosis in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes at different disease course, and the intervention by statins in very elderly patients. J Diabetes Investig 2018; 9: 389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arenillas JF, Álvarez‐Sabín J. Basic mechanisms in intracranial large‐artery atherosclerosis: advances and challenges. Cerebrovasc Dis 2005; 20: 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi N, Lee JY, Sunwoo JS, et al Recently uncontrolled glycemia in diabetic patients is associated with the severity of intracranial atherosclerosis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2017; 26: 2615–2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Esposito L, Saam T, Heider P, et al MRI plaque imaging reveals high‐risk carotid plaques especially in diabetic patients irrespective of the degree of stenosis. BMC Med Imaging 2010; 10: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moreno PR, Murcia AM, Palacios IF, et al Coronary composition and macrophage infiltration in atherectomy specimens from patients with diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2000; 102: 2180–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tavares CA, Rassi CH, Fahel MG, et al Relationship between glycemic control and coronary artery disease severity, prevalence and plaque characteristics by computed tomography coronary angiography in asymptomatic type 2 diabetic patients. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 32: 1577–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mostaza JM, Lahoz C, Salinero‐Fort MA, et al Carotid atherosclerosis severity in relation to glycemic status: a cross‐sectional populationstudy. Atherosclerosis 2015; 242: 377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. AnkuSh AD, Gomes E, Dessai A. Complications in advanced diabetics in a tertiary care centre: a retrospective registry‐based study. J Clin Diagn Res 2016; 10: OC15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]