Abstract

A 38‐year‐old woman with type 1 diabetes, whose fasting plasma glucose levels were >500 mg/dL under 176 U/day of subcutaneous insulin injection, was admitted to Nippon Medical School Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. When insulin was administered intravenously, she was able to maintain favorable glycemic control even under 24 U/day of regular insulin, showing that she was accompanied by subcutaneous insulin resistance. To choose an optimal insulin regimen, we carried out subcutaneous insulin challenge tests without or with heparin mixture, and found a cocktail of insulin lispro and heparin could reduce blood glucose levels markedly. As a consequence, she achieved favorable blood glucose control by continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion of the cocktail. In summary, the insulin and heparin challenge tests are useful for choosing an optimal insulin regimen in cases of subcutaneous insulin resistance.

Keywords: Heparin, Subcutaneous insulin resistance, Type 1 diabetes

Subcutaneous insulin resistance is defined as a lack of biological efficacy of subcutaneously injected insulin despite a retained efficacy of intravenous insulin infusion. Insulin and heparin challenge tests are useful for choosing an optimal insulin regimen in cases of subcutaneous insulin resistance.

Introduction

Subcutaneous insulin resistance (SIR), the rare syndrome proposed by Schneider and Bennett 1 , is defined as a lack of biological efficacy of subcutaneously injected insulin despite a retained efficacy of intravenous insulin infusion. SIR patients tend to be suspected of having an eating disorder or factitious brittle diabetes because of the severe resistance to subcutaneous insulin injection; therefore, appropriate diagnosis of SIR is of great importance. Two mechanisms for the pathogenesis of SIR have been suggested: (i) increased insulin‐degrading activity in subcutaneous tissues 2 ; and (ii) impaired insulin transfer from subcutaneous tissues into the blood circulation 3 . Consequently, serum insulin levels fluctuate widely, resulting in poor glycemic control under subcutaneous insulin injection. Several treatment strategies have been proposed so far 4 , but their efficacies are inconsistent.

Here, we report a case of type 1 diabetes accompanied by SIR who achieved favorable blood glucose control by continuous subcutaneous infusion (CSI) of insulin lispro mixed with heparin. For choosing the regimen, we carried out subcutaneous insulin challenge tests without or with heparin mixture.

Case Report

A 38‐year‐old Japanese woman (69.0 kg, body mass index 24.3 kg/m2) with type 1 diabetes was admitted to Nippon Medical School Hospital, Tokyo, Japan because of poor glycemic control. She was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when she was aged 16 years. Although intensive insulin therapy with a basal–bolus insulin regimen was initiated, her glycated hemoglobin (NGSP) levels remained over 10% and glycemic levels fluctuated widely not only to severe hyperglycemia but also to hypoglycemia. She had been admitted to hospitals 22 times due to diabetic ketoacidosis and severe hypoglycemia. Owing to the unstable glycemic control, we initially suspected eating disorders or intentional insulin overdose associated with psychosocial disorders; for example, Münchausen syndrome. However, when we referred the the patients to the Department of Psychiatry in our hospital, the psychiatric specialist diagnosed her to be in a normal emotional state by the clinical interview. She had diabetic complications including retinopathy (pre‐proliferative), nephropathy (macroalbuminuria), peripheral (numbness in the feet, absent Achilles tendon reflex, loss of vibratory sensation) and autonomic neuropathy (the coefficient of variation of the R‐R interval was 1.08%). Indurated skin lesions were not present at the injection sites. The levels of glycated hemoglobin, GAD antibody and insulin antibody were 12.5%, 6.2 U/mL (reference values <1.4 U/mL) and 2.5% (reference values <0.3%), respectively.

After the admission, insulin preparations were stored in a nurse station and nurses always checked the patient’s insulin injection procedures carefully, and the glucose profile was monitored under the fixed energy intake and exercise levels. Indeed, there were no evident factors to cause unstable glycemic control in her eating behavior and manipulation of insulin injection. She received the same amount of insulin that she had received in the outpatient clinic (104 U/day of regular insulin and 72 U/day of neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin). In fact, the patient had been prescribed 11 and six cartridges (3,300 and 1,800 units) of regular and neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin, respectively, for 1 month at every visit. However, her fasting plasma glucose levels remained >500 mg/dL and eventually she developed diabetic ketosis. We then started continuous venous infusion (CVI) of regular insulin and achieved favorable blood glucose control by 24 U/day. SIR was suspected because of the severe resistance to subcutaneous insulin injection despite the patient’s sensitivity to intravenous insulin infusion.

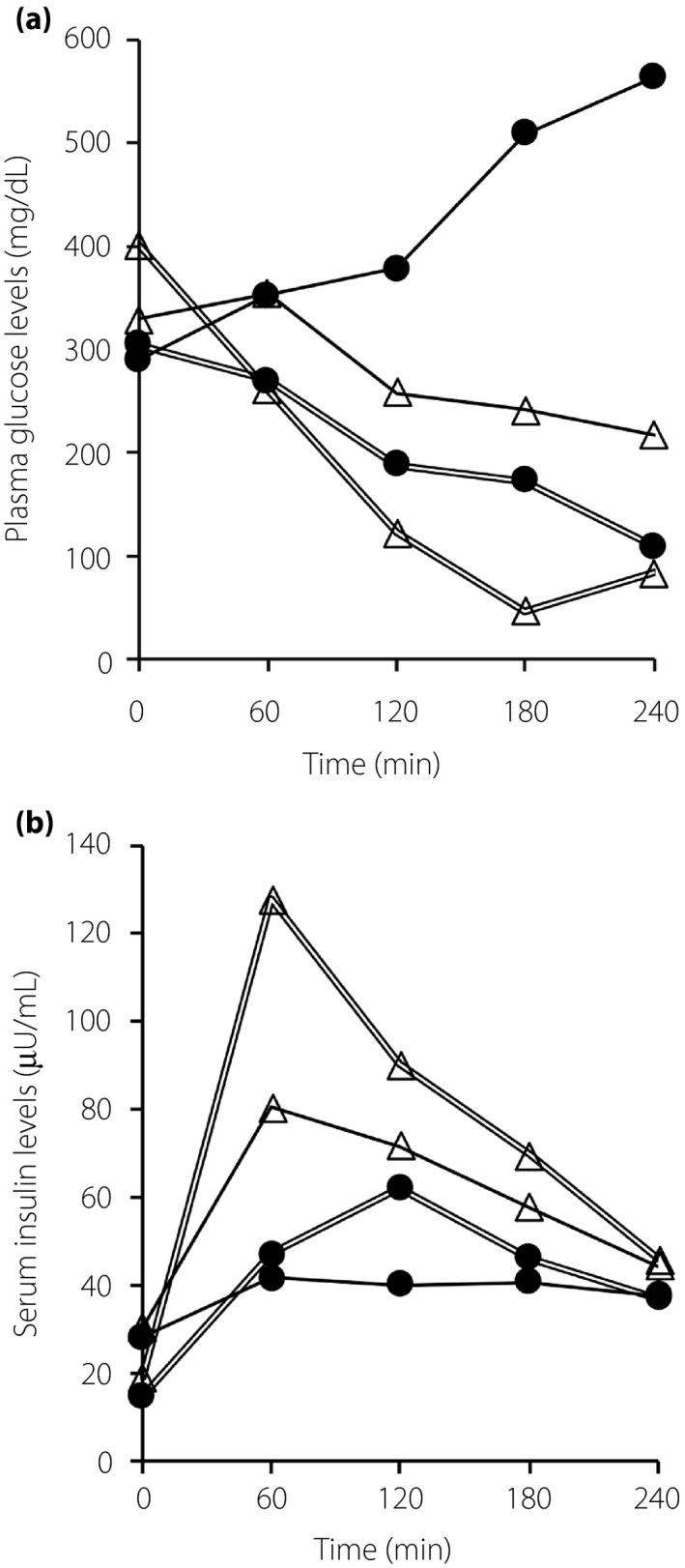

To choose an optimal insulin regimen, we carried out subcutaneous insulin challenge tests without or with heparin mixture, as heparin was suggested to facilitate insulin absorption from subcutaneous tissue to blood vessels. After overnight fasting, regular insulin 10 U or insulin lispro 10 U without or with heparin calcium 100 U was administered subcutaneously over the CVI of regular insulin (1 U/h) as basal insulin. Then, plasma glucose levels (Figure 1a) and serum insulin levels (Figure 1b) were monitored every 60 min for 4 h. The serum insulin levels, including regular insulin and insulin lispro, were measured by a fluorescence enzyme immunoassay kit, E‐test “TOSOH” II (Tosoh Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). As a result, the cocktail of insulin lispro and heparin increased serum insulin levels effectively, and could reduce plasma glucose levels as compared with the other insulin regimens (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Insulin and heparin challenge tests on plasma glucose and serum insulin levels. Regular insulin 10 U (black circles with a solid line), insulin lispro 10 U (white triangles with a solid line), regular insulin 10 U with heparin (black circles with double lines) and insulin lispro 10U with heparin (white triangles with double lines) were administered subcutaneously accompanied by continuous intravenous infusion of regular insulin (1 U/h) as basal insulin. (a) Plasma glucose and (b) serum insulin levels were measured every 60 min for 4 h after each subcutaneous injection.

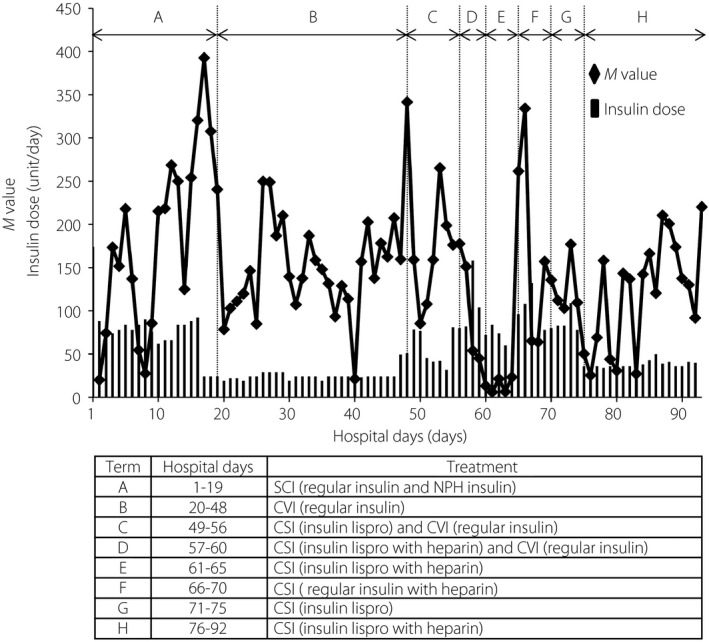

Next, we assessed the daily profile of blood glucose levels (6 times in a day; 00.00, 06.00, 08.00, 12.00, 18.00, 21.00 hours) and calculated the M value as an index of blood glucose control 5 . We also compared the administered insulin doses on the different insulin regimens. The high M values were improved by the CVI of regular insulin accompanied by decreased insulin doses (term B in Figure 2). Based on the results of the challenge tests (Figure 1), we gradually switched from CVI of regular insulin to CSI of insulin lispro with heparin. When CVI of regular insulin was discontinued, CSI of insulin lispro with heparin succeeded to maintain favorable glycemic control, as shown by lower M values with a small increase of insulin dose (term E in Figure 2). Meanwhile, CSI of regular insulin with heparin (term F in Figure 2) or insulin lispro alone (term G in Figure 2) showed higher M values. We therefore concluded CSI of insulin lispro with heparin to be the most appropriate treatment for the patient. Consequently, she could achieve relatively favorable glycemic control with minimal doses of insulin (term H in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Blood glucose profile and administered insulin doses in different insulin regimens. Blood glucose levels were measured six times in a day (00.00, 06.00, 08.00, 12.00, 18.00, 21.00 hours) and calculated M values by the blood glucose profile using the formula described below. The M values and administrated insulin doses are presented as black diamonds with a solid line and black bars, respectively. . CSI, continuous subcutaneous infusion; CVI, continuous venous infusion; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn; SCI, subcutaneous insulin injection.

All the clinical interventions were carried out under the supervision of the institutional ethics committee.

Discussion

In the present case, glycemic control was improved with a marked reduction of insulin dose by CSI of insulin lispro with heparin. The cocktail of insulin lispro and heparin proved to be the best therapy according to the challenge tests of different insulin regimens. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of SIR in regard to the following points: (i) effective therapy was chosen by the challenge tests; and (ii) glucose profiles were monitored on the different insulin regimens.

As SIR is rare and often misdiagnosed, Paulsen et al. 2 proposed a precise definition for SIR according to three criteria: (i) resistance to the action of subcutaneous insulin injection while maintaining sensitivity to intravenous insulin infusion; (ii) a lack of increase in circulatory insulin levels after subcutaneous insulin injection; and (iii) increased insulin degradation activity in the subcutaneous tissue. Insulin degradation activity has been reported to vary according to the site and depth of injections, and skin temperatures 6 . The present case showed brittle glycemic control with both severe hyper‐ and hypoglycemic states over the period of subcutaneous injection of insulin; suggesting that activity of insulin degradation enzymes is inconsistent between each timing of injection. Furthermore, insulin degradation enzymes were not detected in some cases of SIR 7 .

The cocktail of insulin lispro and heparin was reported to be effective in another case of SIR 3 . The proposed mechanism is that insulin lispro is dissociated from hexamers to monomers immediately in the subcutaneous tissue and absorbed into the bloodstream faster than regular insulin 8 . Furthermore, heparin modulates the biological activity of vascular endothelial growth factor, provides interstitial space and facilitates diffusion of water‐soluble molecules 3 , 9 , 10 ; inferring that heparin promotes transportation of injected insulin from the subcutaneous tissue to blood vessels.

From the present case, we suggest that the cocktail of insulin lispro and heparin facilitates the absorption process of injected insulin, and can minimize its degradation in the subcutaneous tissue; therefore, the cocktail is effective in cases of SIR with brittle glycemic control. Hence, insulin and heparin challenge tests are useful for choosing an optimal insulin regimen for cases of SIR.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

None.

J Diabetes Investig 2020; 11: 1370–1373

References

- 1. Schneider AJ, Bennett RH. Impaired absorption of insulin as a cause of insulin resistance. Diabetes 1975; 24: 443. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Paulsen EP, Courtney JW 3rd, Duckworth WC. Insulin resistance caused by massive degradation of subcutaneous insulin. Diabetes 1979; 28: 640–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tokuyama Y, Nozaki O, Kanatsuka A. A patient with subcutaneous‐insulin resistance treated by insulin lispro plus heparin. Diab Res Clin Pract 2001; 54: 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Riveline JP, Vantyghem MC, Fermon C, et al Subcutaneous insulin resistance successfully circumvented on long term by peritoneal insulin delivery from an implantable pump in four diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab 2005; 31: 496–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schlichtkrull J, Munck O, Jersild M. The M‐value, an index of blood‐sugar control in diabetes. Acta Med Scand 1965; 177: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Soudan B, Girardot C, Fermon C, et al Extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance: a misunderstood syndrome. Diab Metab 2003; 29: 539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schade DS, William C, Duckworth MD. In search of the subcutaneous‐insulin‐resistance syndrome. N Engl J Med 1986; 315: 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Henrichs HR, Unger H, Trautmann ME, et al Severe insulin resistance treated with insulin lispro. Lancet 1996; 348: 1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soker S, Svahn CM, Neufeld G. Vascular endothelial growth factor is inactivated by binding to alpha 2‐macroglobulin and the binding is inhibited by heparin. J Biol Chem 1993; 268: 7685–7691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jackson RL, Busch SJ, Cardin AD. Glycosaminoglycans: molecular properties, protein interactions, and role in physiological processes. Physiol Rev 1991; 71: 481–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]