Abstract

Purpose

Recently, the Coalition for Physician Accountability Work Group on Medical Students in the Class of 2021 recommended limiting visiting medical student rotations, conducting virtual residency interviews, and delaying the standard application timeline owing to the ongoing corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. These changes create both challenges and opportunities for medical students and radiation oncology residency programs. We conducted a comprehensive needs assessment to prepare for a virtual recruitment season, including a focus group of senior medical students seeking careers in oncology.

Methods and Materials

A single 1.5-hour focus group was conducted with 10 third- and fourth-year medical students using Zoom videoconferencing software. Participants shared opinions relating to visibility of residency programs, virtual clerkship experiences, expectations for program websites, and remote interviews. The focus group recording was transcribed and analyzed independently by 3 authors. Participants’ statements were abstracted into themes via inductive content analysis.

Results

Inductive content analysis of the focus group transcript identified several potential challenges surrounding virtual recruitment, including learning the culture of a program and/or city, obtaining accurate information about training programs, and uncertainty surrounding the best way to present themselves during a virtual interview season. In the present environment, the focus group participants anticipate relying more on departmental websites and telecommunications because in-person interactions will be limited. In addition, students perceived that the educational yield of a virtual clerkship would be low, particularly if an in-person rotation had already been completed at another institution.

Conclusions

With the COVID-19 crisis limiting visiting student rotations and programs transitioning to hosting remote interviews, we recommend programs focus resources toward portraying the culture of their program and city, accurately depicting program information, and offering virtual electives or virtual interaction to increase applicant exposure to residency program culture.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in the United States led to many changes in medicine, including the popularization of telemedicine visits and the emergence of virtual conferences.1, 2, 3 With the trajectory of the pandemic in flux, the Coalition for Physician Accountability Work Group on Medical Students in the Class of 2021 released a statement affecting medical students applying for residencies in the upcoming 2020 to 2021 interview season with the following points: discouraging away rotations for medical students (except for those pursuing a specialty where no training program is available at the home institution), urging residency programs toward a virtual interview format, and delaying the overall residency application timeline through Electronic Residency Application Service.4 Although the transition to virtual interviews is not unique to the field of academic medicine, a virtual residency recruitment season is unprecedented and will introduce new challenges and alleviate others for both medical students and residency programs.

Radiation oncology (RO) traditionally encourages visiting clerkships/rotations for medical students pursuing the specialty; however, the current public health concerns related to COVID-19 precludes many students from seeking this opportunity. For students without a residency program at their home institution, this may greatly affect their exposure to the field of RO and possibly their likelihood of matching at their training program of choice. For RO residency programs, a virtual interview season heightens existing concerns regarding the declining number of applicants and the increasing number of unfilled positions in the National Residency Matching Program.5 To prepare for the rapidly changing landscape of limited visiting student rotations and the transition to remote interviews, we conducted a comprehensive needs assessment to prepare for a virtual recruitment season. One key component of our needs assessment was a focus group of senior medical students seeking careers in oncology. The purpose of this report is to share the results of a focus group discussion designed to better understand students’ perspectives and concerns about the 2020 to 2021 RO interview season.

Methods and Materials

Third and fourth year medical students were recruited to participate in a single focus group session. Participants were recruited via email to 1 of the following 3 groups of medical students: members of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Oncology Interest Group, UAB medical students who previously expressed interest in an RO residency, and non-UAB medical students who have had prior contact with the UAB Department of RO. Focus group participants provided verbal consent to participate at the beginning of the focus group session and were informed that the session would be recorded and transcribed. Participants were given care packages (< $15 value) for their time. This quality improvement project was reviewed by the UAB institutional review board with a nonhuman subjects research determination.

Data collection

A single 1.5-hour focus group was conducted with 10 student participants (Table 1) using Zoom (San Jose, CA) videoconferencing software. Participants were informed before the focus group that the intent was to hear their opinions about how they anticipate choosing residency programs for applications and interviews during the 2020 to 2021 academic year. An interview guide of questions was developed to encourage focus group participants to share opinions relating to visibility of the residency program, virtual clerkship experiences, expectations for program websites, and remote interviews (Table 2). The interview was led by a single RO resident physician (A.S.).

Table 1.

Demographics of focus group participants

| Frequency (%); mean (± SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Years | 27 (± 2) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 8 (80%) |

| Female | 2 (20%) |

| Class level | |

| MS3 | 9 (90%) |

| MS4 | 1 (10%) |

| Considering radiation oncology career? | |

| Yes | 8 (80%) |

| No | 2 (20%) |

Abbreviation: SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Interview guide questions

Program visibility:

|

Virtual clerkship experience

|

Program website expectations

|

Remote interviews

|

Analysis

The focus group was recorded and transcribed and all participant identifiers were removed. The recording was analyzed using inductive qualitative content analysis as described by Elo and Kyngäs.6 An inductive approach was chosen because the 2020 to 2021 academic year is the first time widespread remote interviewing methods will occur in the residency selection process, and we were not aware of existing content categorization models, and the inductive method involves creating thematic category headings based on the transcript. The first step of the inductive analysis was review of the recording transcript with open coding where elements of participants’ comments were abstracted. The recording and transcript were first reviewed by 3 authors (A.S., S.S., and A.M.). Each reviewer then grouped statements into similar themes and created preliminary labels for each theme. The reviewers then met to discuss categories, attempt to reduce the overall number of categories by combining related observations, and finalize the naming with content-characteristic words. Finally, the resulting thematic headings were ranked by the total number of comments and amount of discussion time spent pertaining to each theme.

Results

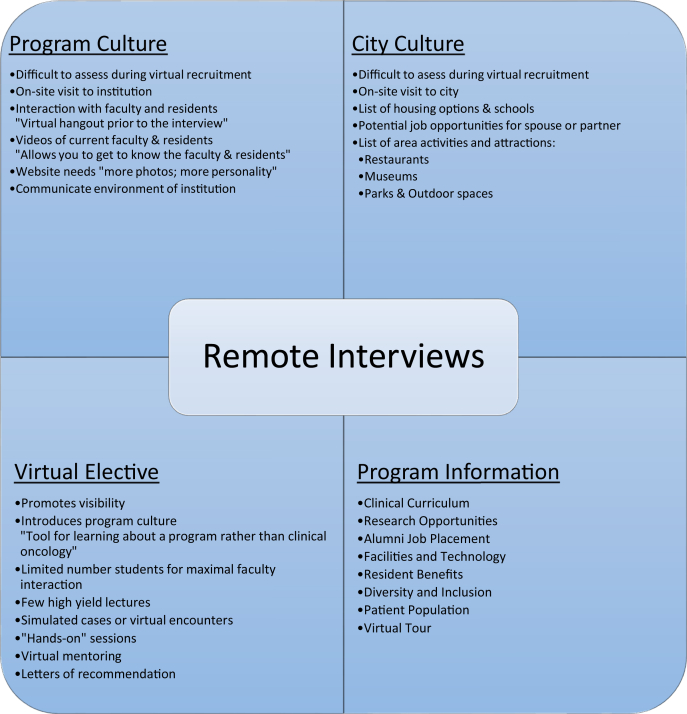

Statements taken from the interview transcript were grouped into a content categorization matrix (Fig 1). Inductive content analysis revealed 3 major themes that were consistent across the content categories. We list each theme, from most to fewest comments, summarize student participants’ concerns, and enumerate student participants’ suggestions for program action items to address these concerns.

Figure 1.

Categorization matrix.

Theme 1: Anticipated challenges to learn about the culture of a residency program and city (most comments)

Concerns for learning about program culture

Students expressed specific fears regarding the lack of opportunity for interaction with the faculty and residents and opportunity to experience the culture of the program in a virtual interview environment. One participant noted, “Understanding [program culture] is a big thing without having face-to-face interactions.” Another remarked, “We need something to bridge the gap to give us insight into who we’d be working with.”

Recommendations:

-

•

Focus group participants suggested creating opportunities for prospective applicants to interact with the department, including offering a virtual elective, inviting applicants to virtual conferences (journal club or didactic lectures), and adding short videos of the faculty or residents on the program website.

-

•

Students strongly supported hosting a videoconference social event with current residents, similar to the traditional preinterview dinner.

Concerns learning about the city where programs are located

Applicants desire to understand residents’ lifestyles outside the hospital and to experience the culture of the city where a RO program is located. However, virtual recruitment will limit applicants from having time to explore the area, and focus group participants expressed concern about moving to an unfamiliar city.

Recommendations:

-

•

100% of those interviewed favored an on-site visit to cities of RO programs during the interview season.

-

•

With the uncertainty of travel amid the COVID-19 epidemic, participants suggested creating a dedicated webpage highlighting housing options, restaurants, nightlife, and area attractions.

-

•

Additionally, participants suggested offering 1:1 phone calls with current residents and faculty to discuss lifestyle and quality of life in the location of the program.

Theme 2: Obtaining accurate objective information about residency programs (moderate comments)

Concerns about obtaining accurate program information

Applicants research residency programs’ training curricula using program website information, peer reference, and web-hosted message boards. Participants detailed the lack of accuracy of some of these resources, and they expressed concern regarding their ability to find all desired program information through a program website. Applicants also fear some questions will go unanswered that are often discussed during an in-person interview.

Recommendations:

-

•

Focus group participants strongly rely on program websites for information; therefore, the website should be kept current and easy to navigate.

-

•

Students reported that many details about programs may become lost in large bodies of text. They felt that short videos would be a preferred means of communicating information, with the added benefit of demonstrating program personality and culture.

-

•

Participants suggested “more photos, more people, more personality” when looking at multiple RO program websites. Specific components of what participants want as far as website design and information are detailed in Table 3.

-

•

Participants also suggested creation of a separate website portal specifically for students who were invited to interview at a program. This website would detail information about the virtual interview, provide a virtual tour of the department, and invite applicants to a virtual hangout with current residents (replacing the preinterview dinner). This site would ideally be privately hosted, with a link sent directly to applicants once interview invitations are extended.

Table 3.

Elements of website

| Element of website | Description of content |

|---|---|

| Clinical activities | Students seek curriculum information including clinic rotation structure (with sample rotation schedule graphic), didactic program information, and current resident biographies. |

| Research opportunities | 70% of interview participants reported looking at faculty- and resident-published research when investigating an RO training program. Applicants desire information on program and institutional research opportunities, including details on the research mentoring structure of an institution. Current resident presentations and publications are also of interest. |

| Job placement | 100% of participants agreed job placement is of significant concern and listing program alumni on the website would demonstrate graduates’ success securing desirable jobs. Students were also interested in reading published data from recent job entry surveys and recommended offering links to published resources on a program’s website.7 |

| Facilities and technology | Applicants requested facility details including number of training sites, number and types of machines and treatment modalities used (including proton therapy, if available). |

| Resident benefits | Salaries, insurance coverage, vacation time, sick leave, and parental leave benefits were desired to be detailed on the website. In addition, applicants seek information about conference attendance and expenses, educational resources (ie, journal access, book stipends), and other institutional perks. |

Abbreviation: RO = radiation oncology.

Concern about how to best present self during rotation season (fewest comments)

Concerns about a virtual elective

Students were concerned that a visiting virtual elective would have low educational yield if previous in-person RO rotations had been completed. One student said, “There isn’t anything you’d learn doing telemedicine that you wouldn’t learn in person, but you could learn from conferences and opportunities to work with residents/faculty for contouring & treatment planning.” Another stated a virtual elective could be “a tool for learning about a program, rather than learning clinical oncology.”

Recommendations:

-

•

To date, virtual electives in RO have focused on providing clinical RO lectures and patient encounters.8

-

•

Students pursuing RO appear to prefer fewer didactic sessions and more opportunities for active learning. Specific examples provided by the participants were contouring, beam placement, and plan review to facilitate interactions with faculty and residents.

-

•

Programs should be aware that goals of participating in a virtual visiting elective likely include exposure to the program’s culture, experiencing intentional mentoring, and possibly obtaining strong letters of recommendation for RO residency application.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected and will continue to affect radiation oncologists as well as medical students with interest in RO across the United States. Based on recommendations from the Coalition for Physician Accountability Work Group on Medical Students in the Class of 2021, visiting medical student rotations are discouraged, the residency interview process will be virtual, and the standard application timeline has been delayed. These changes create both challenges and opportunities for medical students and RO residency programs. As the number of RO applicants has declined over the past few years with a resultant increase in the number of unfilled positions in the National Resident Matching Program Match, there is increased pressure for RO departments to be viewed positively by prospective applicants. RO residency programs are faced with obstacles directly related to the current climate; however, there are several opportunities for forward-thinking programs to successfully adapt to the changing times. To better understand medical students’ perspectives, we developed a focus group as a component of a comprehensive needs assessment regarding the 2020 to 2021 RO interview season. The focus group identified several potential challenges, including learning the culture of a program and/or city, obtaining accurate information about training programs, and uncertainty surrounding the best way to present themselves during a virtual interview season.

The anticipated challenges of learning about the culture of a residency program and city was the most commented-on theme by the focus group participants. We were not surprised to hear that students were concerned about learning about program culture because this is a recognized aspect by which students judge programs9, 10, 11; however, the depth of this concern was greater than expected. Students indicated that the key way in which they were planning to assess departmental culture was by in-person interaction, either with an elective clerkship or on interview day. In the present environment, the focus group participants anticipate relying more on departmental websites and telecommunications.

Focus group participants believed that obtaining accurate information about a training program represented an additional potential barrier created by the virtual interview season. Participants reported relying more heavily on third-party resources, such as community spreadsheets and message boards, than information posted on program websites. Residency websites were noted to have overall low appeal due to outdated or incomplete information and not addressing key elements of how students evaluate programs, in terms of both qualitative (training environment, culture, diversity) and quantitative (program structure, pay and benefits, research support) characteristics. Concerns about postresidency employment were mentioned by focus group participants who were familiar with discussion boards and recent publications on this topic.12, 13, 14 Program websites may provide an opportunity to showcase alumni in clinical practice and other alumni achievements. The suggestion for a distinct portal or website for invited interview applicants was also unique and merits highlighting as this would allow for a more individualized experience for applicants to learn about the virtual interview process, take a virtual tour of the department and learn several other important pieces of information about a program.

Virtual student clerkships are now offered at many institutions and have been met with positive discussion among RO educators.8 We were therefore surprised that the overall tone of our student participants was lukewarm about participating in a virtual clerkship. The main reason cited by students was the fact that patient encounters using videoconferencing software are a poor substitute for in-person interaction, and the yield of additional didactic lectures before dedicated residency training was also questioned. Students were also concerned that a remote format limits their ability to showcase clinical skills, and this challenge may not be appreciated by program faculty. The value of additional elective rotations was previously discussed by Jang et al,15 who highlighted that students spend up to 25% of their medical school time participating in RO electives at the expense of training in other fields. The main perceived value of a virtual elective in the 2020 to 2021 RO academic year was for applicants to gain an understanding of the culture of a program. With these aspects in mind, our institution’s virtual elective rotation was shortened to 2 weeks, didactic sessions limited to 2 hours per day, and active learning sessions (eg, treatment planning) with faculty mentors were incorporated. Our goals are to provide exposure that supplements an in-person clerkship rather than trying to duplicate it and maximize exposure to program faculty while simultaneously respecting students’ time and priorities.

This focus group was conducted as a quality improvement project to prepare for the 2020 to 2021 interview season. The purpose of this report is to summarize and share the results of the focus group as a resource to better understand students’ concerns and to identify specific action items for residency programs. The main limitation of this work is that the challenges and behaviors of students are anticipated rather than observed; however, we will only have observational data about the challenges of this interview cycle after it is over. This focus group was also comprised of a limited number of participants from a limited number of institutions and was centered around quality improvement at our institution. Whether this group’s participants’ opinions generalize those of the applicant pool at large is unknown, but we believe that the major themes of this discussion are highly relevant to RO residency programs during the upcoming application cycle.

This report summarizes a group of medical students’ specific perspectives on the virtual interview season and introduces thematic categories that contribute toward the development of a conceptual framework for better understanding student perspectives in future projects. Though preliminary, a number of opportunities were identified for RO programs to attract highly qualified candidates by demonstrating their commitment to trainee education, even during a pandemic. With the COVID-19 crisis limiting visiting student rotations and programs transitioning to hosting remote interviews, we recommend programs focus resources toward portraying the culture of their program and city, accurately depicting program information, and offering opportunities for virtual electives that increase applicant exposure to residency program culture.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This work had no specific funding.

Disclosures: The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest associated with this work.

Data are not available at this time. Please do not use the word research since this is a quality improvement study rather than research.

References

- 1.Hollander J.E., Carr B.G. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. New Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Contreras C.M., Metzger G.A., Beane J.D., Dedhia P.H., Ejaz A., Pawlik T.M. Telemedicine: Patient-provider clinical engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J Gastro Surg. 2020;24:1692–1697. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04623-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dharmarajan H., Anderson J.L., Kim S. Transition to a virtual multidisciplinary tumor board during the COVID-19 pandemic: University of Pittsburgh experience. Head & Neck. 2020;42:1310–1316. doi: 10.1002/hed.26195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coalition for Physician Accountability. Final Report and Recommendations for Medical Education Institutions of LCME-Accredited, U.S. Osteopathic, and Non-U.S. Medical School Applicants. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-05/covid19_Final_Recommendations_Executive%20Summary_Final_05112020.pdf Available at:

- 5.Kharofa J., Tendulkar R., Fields E., Beriwal S., Attia A., Olivier K. Cleaning without SOAP: How program directors should respond to going unmatched in 2020. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106:241–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elo S., Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollom E.L., Sandhu N., Frank J. Continuing medical student education during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Development of a virtual radiation oncology clerkship. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020;5:732–736. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao H., Souders C.P., Freedman A., Breyer B.N., Anger J.T. The applicant's perspective on urology residency interviews: A qualitative analysis. Urology. 2020;142:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yousuf S.J., Kwagyan J., Jones L.S. Applicants' choice of an ophthalmology residency program. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:423–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeSantis M., Marco C.A. Emergency medicine residency selection: Factors influencing candidate decisions. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:559–561. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lefresne S., Giambattista J., Ingledew P.A., Carolan H., Olson R.A., Loewen S. Radiation oncology resident and program director perceptions of the job market and impact on well-being. Cureus. 2020;12 doi: 10.7759/cureus.7187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn J., Goodman C.R., Albert A. Top concerns of radiation oncology trainees in 2019: Job market, board examinations, and residency expansion. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sura K., Lischalk J.W., Grills I.S., Mundt A.J., Wilson L.D., Vapiwala N. Modern perspectives on radiation oncology residency expansion, fellowship evolution, and employment satisfaction. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16:749–753. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang S., Rosenberg S.A., Hullet C., Bradley K.A., Kimple R.J. Value of elective radiation oncology rotations: How many is too many? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100:558–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royce T., Doke K., Wall T. The employment experience of recent graduates from US radiation oncology training programs: The practice entry survey results from 2012 to 2017. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16 doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]