Abstract

A stereoselective entry to ryanoids is described that culminates in the synthesis of anhydroryanodol and, thus, the formal total synthesis of ryanodol. The pathway described features an annulation reaction conceived to address the uniquely complex and highly oxygenated polycyclic skeleton common to members of this natural product class. It is demonstrated that metallacycle-mediated intramolecular coupling of an alkyne and a 1,3-diketone can proceed with a highly functionalized enyne and with outstanding levels of stereoselection. Further, the first application of this technology in natural product synthesis is demonstrated here. More broadly, the advances described demonstrate the value that programs in natural product total synthesis have in advancing organic chemistry, here through the design and realization of an annulation reaction that accomplishes what previously established reactions do not.

Graphical Abstract

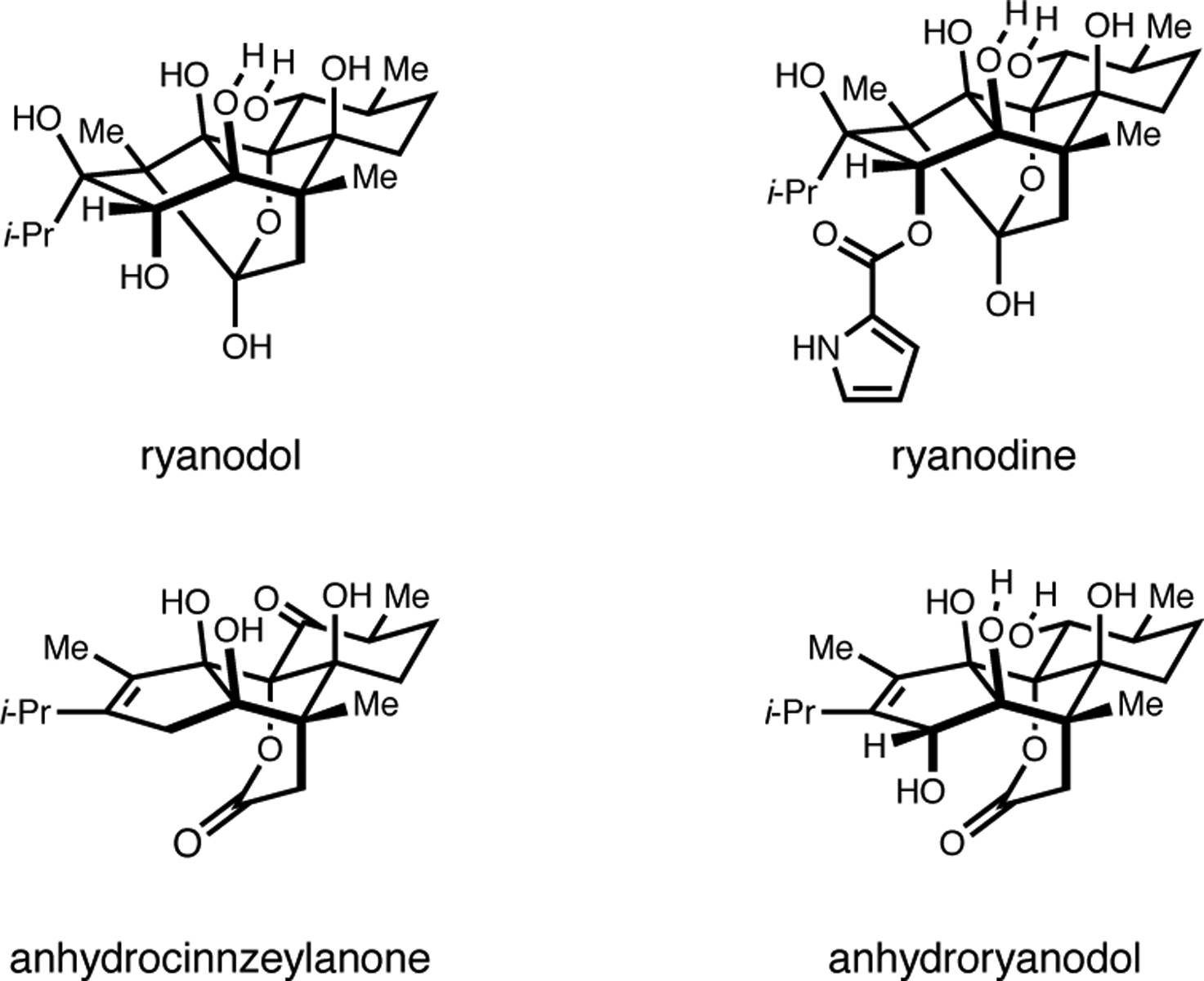

Natural product total synthesis continues to serve as an enduring platform for the evolution of organic chemistry. It provides seemingly endless inspiration for the design and development of new chemical reactions and offers unique opportunities to discover modes of reactivity associated with novel structurally complex intermediates. Densely functionalized diterpenoids have served well in this regard, with ryanoids being particularly compelling (Figure 1).1–4 The natural product ryanodine, isolated from the South American plant Ryana speciosa Vahl, and its hydrolysis product ryanodol, are examples that, aside from their compelling structures, are known to regulate a family of Ca2+ ion channels.5 These molecules first stood as complex problems for structure elucidation due, in part, to the large number of fully substituted carbon atoms in their polycyclic skeletons. Following years of study, Wiesner reported the structure of ryanodine in 1967 through an effort that was later described by Deslongchamps as “one of the most brilliant accomplishments in structure elucidation using chemical degradation.”6, 1b Ryanodine and ryanodol are exceptionally daunting targets for de novo synthesis, being comprised of five distinct ring systems that contain eleven stereogenic centers, eight of which are contiguous fully substituted sp3 carbon atoms (including two quaternary centers). To date, several total syntheses of these targets have been reported, all of which mark substantial achievements in the discipline.1–3 The first was Deslongchamps’ synthesis of ryanodol that harnessed the power of Diels–Alder chemistry, Baeyer–Villiger oxidation, and a novel oxidative cleavage/transannular aldol cascade.1 Notably, these studies served to nurture the group’s interest in the role that stereoelectronic effects play in organic chemistry.7 Inoue reported the second synthesis of a ryanoid that embraced symmetry in synthesis design, and capitalized on the strategic use of radical allylation, Pd-catalyzed olefin isomerization, and ring-closing metathesis chemistry.2 Most recently, Reisman achieved a stunningly step-economical synthesis of ryanodol that featured a Rhcatalyzed Pauson–Khand reaction and a SeO2-mediated polyoxidation process.3 Here, we describe a conceptually unique approach to the ryanoids that has culminated in the synthesis of (+/−)-anhydroryanodol (Figure 1), a degradation product of ryanodine8 and a common late stage intermediate in previously reported total syntheses of ryanodol.1,3 Distinct from earlier approaches, the numerous challenges posed by the structure of ryanodol were employed to inspire the invention of an annulation reaction capable of accomplishing carbocycle formation in concert with the stereoselective establishment of numerous consecutive tertiary alcohols/ethers.9 Here, we describe the application of this type of carbocycle-forming process to the preparation of (+/−)-anhydroryanodol, culminating in a novel formal synthesis of ryanodol.

Figure 1.

Introduction to ryanoids and anhydroryanodol.

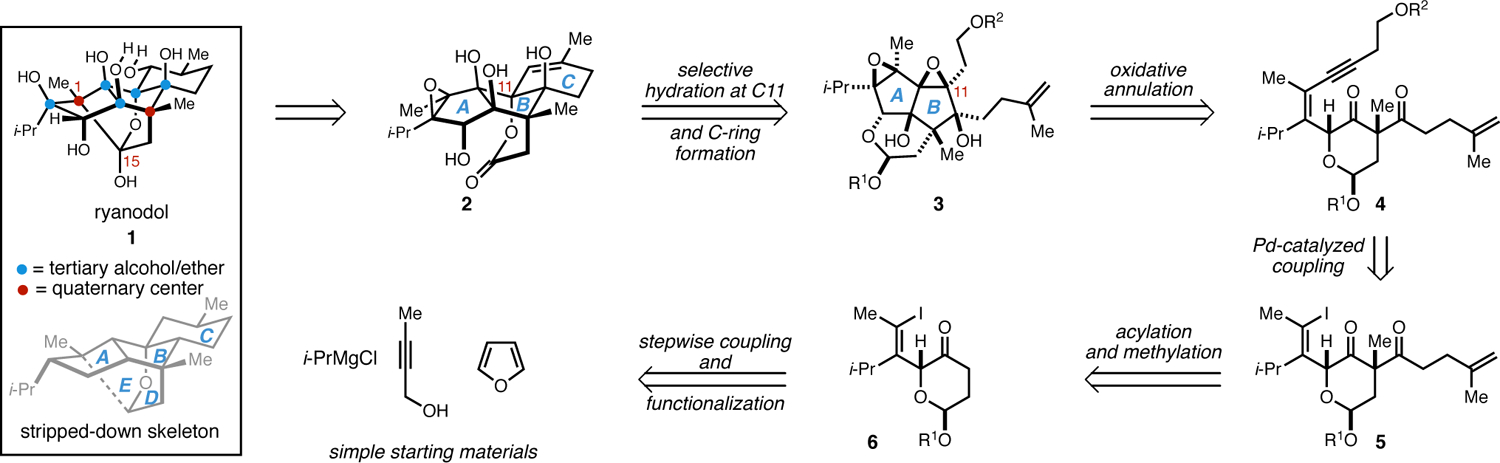

Our efforts began by targeting the construction of ryanodol (1) as depicted in Figure 2, relying on construction of the C1–C15 bond through the use of reductive cyclization technology pioneered by Deslongchamps and later leveraged by Reisman.1,3 The proposed late-stage densely oxygenated tetracycle 2 was thought to be accessible from the tricyclic di-epoxide 3 through: (1) conversion of the acetal to the lactone, (2) saponification followed by selective epoxide opening at C11, and (3) ring-closing olefin metathesis to establish the C-ring. Compound 3 was viewed as the product of an oxidative metallacycle-mediated annulation reaction of the enyne 4, itself deemed accessible from ketone 5 and ultimately from vinyliodide 6, which would be prepared from stepwise coupling of readily available starting materials (i-PrMgCl, 2-butyne-1-ol, and furan).

Figure 2.

Initial retrosynthetic analysis of ryanoids featuring an oxidative annulation reaction between an enyne and a 1,3-diketone.

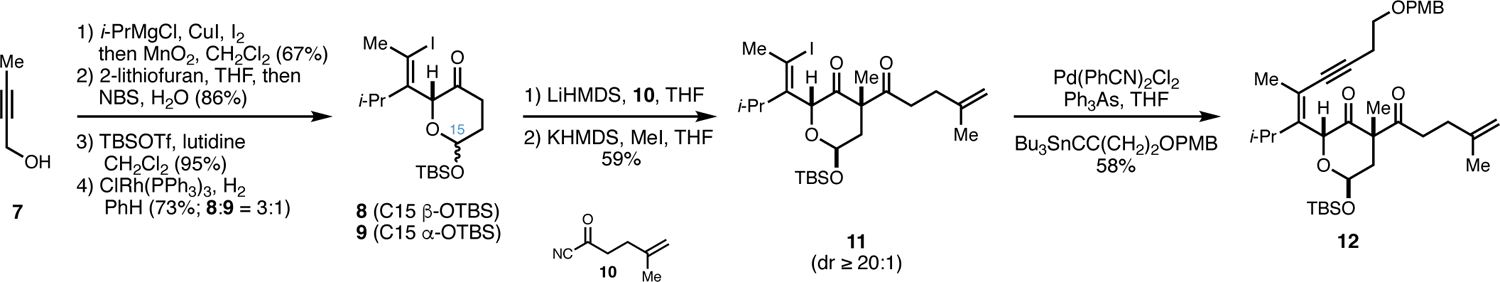

Construction of the polyunsaturated substrate of interest (12) for the planned oxidative annulation is presented in Figure 3. Initial copper-mediated addition of i-PrMgCl to the commercially available alkyne 710 was followed by quenching of the resulting organ-ometallic intermediate with iodine to deliver a stereodefined tetrasubstituted vinyl iodide. Subsequent oxidation to the corresponding α,β-unsaturated aldehyde was accomplished by the action of MnO2, and conversion to the protected hemiacetal 8 was achieved through a sequence consisting of 1,2-addition of 2-lithiofuran, Achmatowicz rearrangement,11 silylation of the resulting hemiacetal and selective hydrogenation of the enone with Wilkinson’s catalyst.12 While the stereochemistry of the acetal was deemed inconsequential for future transformations, a single isomer (8) was selected for advancement to simplify the practical challenges associated with complex molecule synthesis, including those that surface with respect to compound characterization.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of the annulation substrate 12.

Moving forward, acylation of the kinetic enolate of 8 with the acylcyanide 10 delivered an intermediate 1,3-diketone that was easily methylated to deliver the 1,3-diketone 11 (dr ≥ 20:1). Finally, Sonogashira coupling13 to install the requisite enyne was successful (<45%), albeit inferior to Stille coupling14 as a means to generate substantial quantities of enyne 12 (58%).

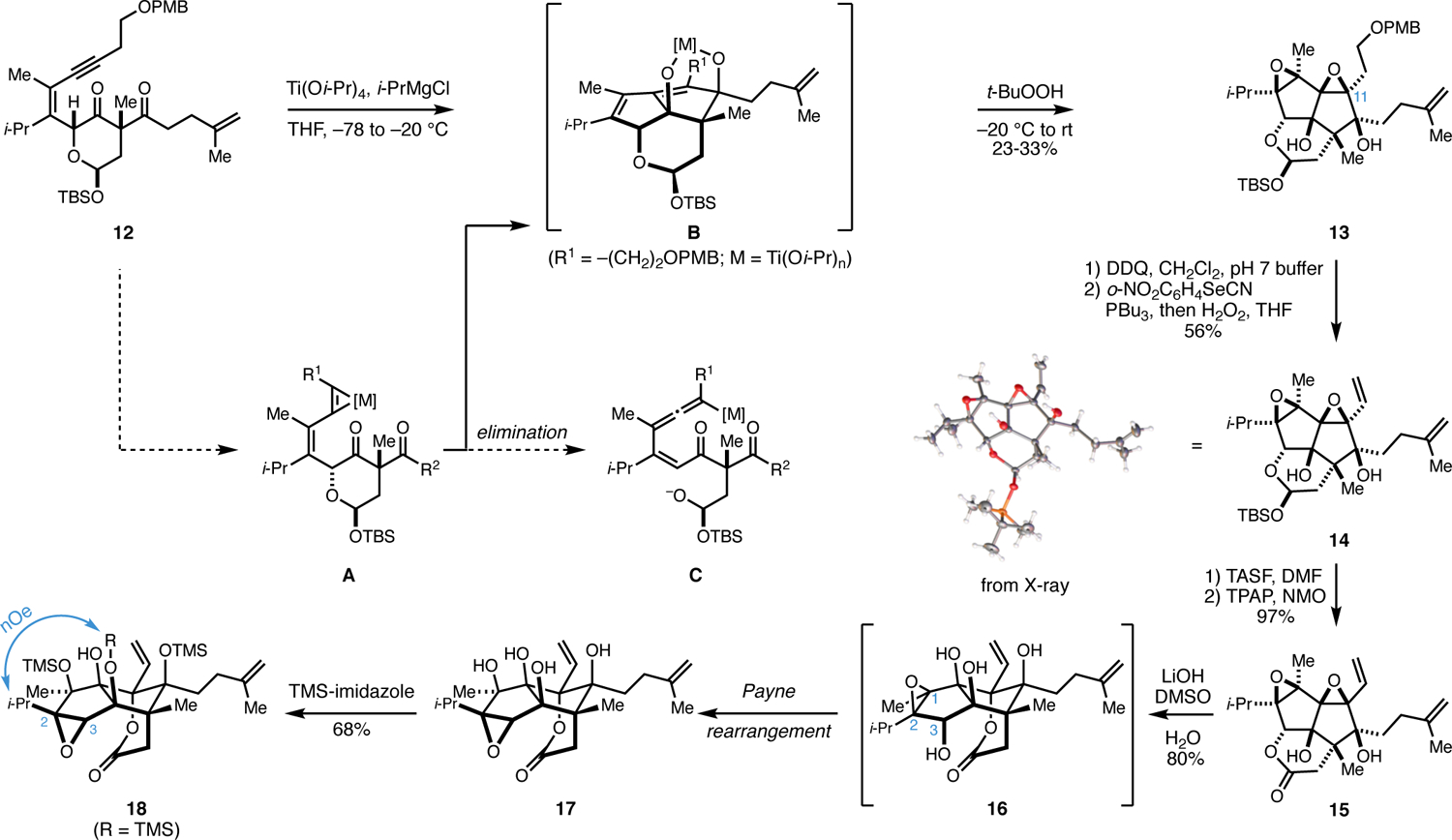

Attention was then focused on realizing a metallacycle-mediated oxidative annulation reaction to forge the AB-ring system. As illustrated in Figure 4, initial concern existed with the planned annulation, as the expected metallacyclopropene of 12 (intermediate A) was thought capable of undergoing two distinct molecular transformations: (1) the desired sequential stereoselective addition to the 1,3-diketone en route to intermediate B, or (2) an undesired elimination to furnish intermediate C. Fortunately, exposure of 12 to the combination of Ti(Oi-Pr)4 and i-PrMgCl, first at −78 °C with warming to −20 °C, followed by oxidative quenching with t-BuOOH delivered the desired tricyclic di-epoxide 13 as a single stereoisomer in 23–33% yield (unoptimized). Notably, while the yield of this reaction was modest at best, and efforts were not made to optimize this transformation for reasons that will be clarified later, the reaction process established the fully oxidized AB ring system of ryanodol through the generation of two C–C bonds, four C–O bonds, and six contiguous stereocenters.

Figure 4.

Investigation of an oxidative annulation and observation of an undesired late-stage Payne rearrangement.

With the densely oxygenated system 13 in hand, attention was directed toward accomplishing chemo- and site-selective hydration at C11. To accomplish this, the following four-step sequence was employed: (1) removal of the PMB ether (DDQ),15 (2) Grieco elimination16 to generate the vinyl epoxide 14, an intermediate whose structure was supported with X-ray diffraction, (3) desilylation by exposure to TASF,17 (4) oxidation to the lactone 15,18 followed by (5) treatment with aqueous base. While this sequence of steps did lead to a product formed from selective epoxide opening at C11, it appeared (after silylation of 17 with TMS-imidazole) to unfortunately possess an undesired C2–C3 epoxide (18) resulting from unanticipated Payne rearrangement.19 Given our goal of preparing a late stage intermediate compatible with Deslongchamps’ final reductive cyclization (Figure 1), this C2–C3 epoxide isomer was deemed not useful.20

To avoid the undesired Payne rearrangement that disrupted the epoxy alcohol motif of 16, an alternative synthesis pathway was conceived. In short, it was thought that the key metallacycle-mediated annulation reaction could be followed by a single epoxidation of the C11–C12 alkene, leaving the C1–C2 alkene in place. If achievable, the late stage lactone hydrolysis and regioselective epoxide opening at C11 would occur with a substrate that could not undergo Payne rearrangement, as it would not contain the C1–C2 epoxide.

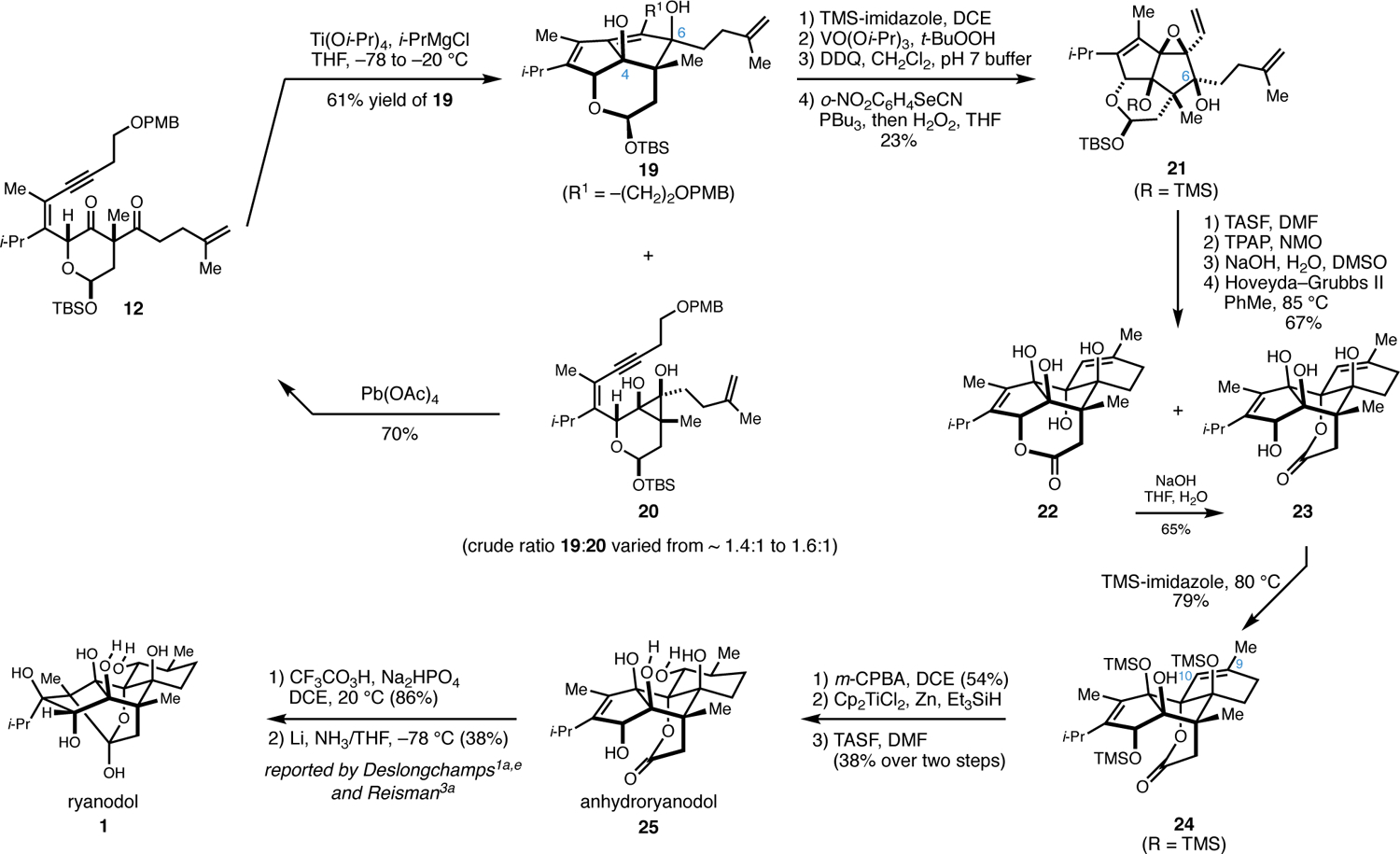

As illustrated in Figure 5, Ti-mediated annulation of 12 was conducted without oxidative termination to deliver the desired product 19 in 61% yield.21 Surprisingly, this reaction routinely delivered a mixture of products (~1.4:1 to ~1.6:1) containing a minor amount of an undesired cyclopropane (20), apparently derived from stereoselective reductive cyclization of the 1,3-diketone of 12. This undesired cyclopropane-containing product could be converted back to the 1,3-diketone starting material 12 by simply stirring with Pb(OAc)4. Moving forward, 19 was converted to the divinyl epoxide 21 by site-selective protection of the C4 hydroxy group as its corresponding TMS ether through the action of TMS-imidazole (DCE, rt), followed by a relatively straightforward sequence of functional group manipulations (directed epoxidation, deprotection of the PMB ether, and Grieco elimination).

Figure 5.

Preparation of (+/−)-anhydroryanodol from 1,3-diketone 12; formal total synthesis of (+/−)-ryanodol.

Moving forward, 21 was desilylated (TASF in DMF), and the resulting hemiacetal was oxidized to the corresponding lactone (TPAP, NMO). Treatment with NaOH in wet DMSO, was then followed by ring-closing metathesis22 to deliver a roughly equal mixture of lactone isomers 22 and 23 in 67% yield over the four-step sequence. Notably, the lactone isomer 22 could be equilibrated by the action of NaOH in THF/H2O to deliver a 5:1 mixture of lactone isomers favoring 23. Purification after this equilibration delivered an additional 65% yield of lactone isomer 23.

Next, selective partial silylation of 23 was accomplished by treatment with neat TMS-imidazole (80 °C), delivering 24 in 79% yield. Finally, 24 was converted to (+/−)-anhydroryanodol (25) by selective hydration of the C9–C10 alkene and global desilylation. This was accomplished through chemo- and stereoselective epoxidation (m-CPBA), reductive cleavage of the resulting epoxide (Cp2TiCl2, Zn, Et3SiH)23 and treatment with TASF. Notably, anhydroryanodol (25) has been converted to ryanodol by both Deslongchamps1a,e and Reisman,3a through a simple two-step sequence of stereoselective epoxidation (CF3CO3H, Na2HPO4, DCE) and reductive cyclization (Li/NH3).

Overall, a synthesis of (+/−)-anhydroryanodol has been achieved through a synthesis pathway based on a fundamentally new retrosynthetic strategy for carbocycle synthesis. While demonstrating the power of a metallacycle-mediated intramolecular alkyne–diketone coupling reaction, these studies highlight the enduring value of natural product total synthesis as stimulus for the design and development of new reactions in organic chemistry. Finally, the chemistry that has emerged from these pursuits, while being stimulated by the intricate structure of a single natural product target, is of great interest for addressing a range of challenging structural problems in target-oriented synthesis, and efforts along these lines will be the focus of ongoing pursuits.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge financial support of this work by the National Institutes of Health - NIGMS (R01 GM124004 and R35 GM134725).

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION PARAGRAPH:

Experimental procedures and tabulated spectroscopic data for new compounds (PDF) are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/page/jacsat/submission/authors.html.

Accession Codes: CCDC 2004970 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for compound 14 depicted in Figure 3B. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing dat_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax +44 1223 336033.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Bélanger A; Berney DJF; Borschberg HJ; Brousseau R; Doutheau A; Durand R; Katayama H; Lapalme R; Leturc DM; Liao C-C; Maclachlan FN; Maffrand JP; Marazza F; Martino R; Moreau C; Saintlaurent L; Saintonge R; Soucy P; Ruest L; Deslongchamps P Total Synthesis of Ryanodol. Can. J. Chem 1979, 57, 3348–3354. [Google Scholar]; (b) Deslongchamps P; Bélanger A; Berney DJF; Borschberg HJ; Brousseau R; Doutheau A; Durand R; Katayama H; Lapalme R; Leturc DM; Liao C-C; Maclachlan FN; Maffrand JP; Marazza F; Martino R; Moreau C; Ruest L; Saintlaurent L; Saintonge R; Soucy P The Total Synthesis of (+)-Ryanodol. 1. General Strategy and Search for a Convenient Diene for the Construction of a Key Tricyclic Intermediate. Can. J. Chem 1990, 68, 115–126. [Google Scholar]; (c) Deslongchamps P; Bélanger A; Berney DJF; Borschberg HJ; Brousseau R; Doutheau A; Durand R; Katayama H; Lapalme R; Leturc DM; Liao C-C; Maclachlan FN; Maffrand JP; Marazza F; Martino R; Moreau C; Ruest L; Saintlaurent L; Saintonge R; Soucy P The Total Synthesis of (+)-Ryanodol. 2. Model Studies for Ring B and Ring C of (+)-Anhydroryanodol. Preparation of a Key Pentacyclic Intermediate. Can. J. Chem 1990, 68, 127–152. [Google Scholar]; (d) Deslongchamps P; Bélanger A; Berney DJF; Borschberg HJ; Brousseau R; Doutheau A; Durand R; Katayama H; Lapalme R; Leturc DM; Liao C-C; Maclachlan FN; Maffrand JP; Marazza F; Martino R; Moreau C; Ruest L; Saintlaurent L; Saintonge R; Soucy P The Total Synthesis of (+)-Ryanodol. 3. Preparation of (+)-Anhydroryanodol from a Key Pentacyclic Intermediate. Can. J. Chem 1990, 68, 153–185. [Google Scholar]; (e) Deslongchamps P; Bélanger A; Berney DJF; Borschberg HJ; Brousseau R; Doutheau A; Durand R; Katayama H; Lapalme R; Leturc DM; Liao C-C; Maclachlan FN; Maffrand JP; Marazza F; Martino R; Moreau C; Ruest L; Saintlaurent L; Saintonge R; Soucy P The Total Synthesis of (+)-Ryanodol. 4. Preparation of (+)-Ryanodol from (+)-Anhydroryanodol. Can. J. Chem 1990, 68, 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Urabe D; Nagatomo M; Hagiwara K; Masuda K; Inoue M Symmetry-driven synthesis of 9-demethyl-10,15-dideoxyranodol. Chem. Sci 2013, 4, 1615–1619. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nagatomo M; Koshimizu M; Masuda K; Tabuchi T; Urabe D; Inoue M Total Synthesis of Ryanodol. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 5916–5919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nagatomo M; Hagiwara K; Masuda K; Koshimizu M; Kawamata T; Matsui Y; Urabe D; Inoue M Symmetry-Driven Strategy for the Assembly of the Core Tetracycle of (+)-Ryanodine: Synthetic Utility of a Cobalt-Catalyzed Olefin-Oxidation and a-Alkoxy Bridgehead Radical Reaction. Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22, 222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Masuda K; Koshimizu M; Nagatomo M; Inoue M Asymmetric Total Synthesis of (+)-Ryanodol and (+)-Ryanodine. Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22, 230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Chuang KV; Xu C; Reisman SEA 15-step synthesis of (+)-ryanodol. Science, 2016, 353, 912–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu C; Han A; Virgil SC; Reisman SE Chemical Synthesis of (+)-Ryanodine and (+)-20-Deoxyspiganthine. ACS Central Sci. 2017, 3, 278–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Han A; Tao Y; Reisman SEA 16-step synthesis of the isoryanodane diterpene (+)-perseanol. Nature, 2019, 573, 563–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wood JL; Graeber JK; Njardarson JT Application of phenolic oxidation chemistry in synthesis: preparation of the BCE ring system of ryanodine. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 8855–8858. [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Rogers EF; Koniuszy FR; Shavel J; Folkers K Plant Insecticides. 1. Ryanodine, a new alkaloid from Ryania speciose Vahl. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1948, 70, 3086–3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) González-Coloma A; Cabrera R; Socorro Monzón AR; Fraga BM Persea Indica as a Natural Source of the Insecticide Ryanodol. Phytochemistry, 1993, 34, 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Wiesner K; Valenta Z; Findlay JA The Structure of ryanodine. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 8, 221–225. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wiesner K The Structure, Stereochemistry and Absolute Configuration of Anhydroryanodine. Pure Appl. Chem 1963, 7, 285–296. [Google Scholar]; (c) Srivastava SN; Przybylska M The molecular structure of the ryanodol-p-bromo benzyl ether. Can. J. Chem 1968, 46, 795–797. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Deslongchamps P Stereoelectronic Effects in Organic Chemistry; Baldwin JE, Ed.; Pergamon Press, Inc.: 1983, Oxford, U.K.; p 375. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ruest L; Deslongchamps P Ryanoids and Related Compounds. A Total Synthesis of 3-epiryanodine. Can. J. Chem 1993, 71, 634–638. [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Kier MJ; Leon RM; O’Rourke NF; Rheingold AL; Micalizio GC Synthesis of Highly Oxygenated Carbocycles by Stereoselective Coupling of Alkynes to 1,3- and 1,4-Dicarbonyl Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 12374–12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Du K; Kier MJ; Rheingold AL; Micalizio GC Toward the Total Synthesis of Ryanodol via Oxidative Alkyne–1,3-Diketone Annulation: Construction of a Ryanoid Tetracycle. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 6457–6461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Millham AB; Kier MJ; Leon RM; Karmakar R; Stempel ZD; Micalizio GC A Complementary Process to Pauson–Khand-Type Annulation Reactions for the Construction of Fully Substituted Cyclopentenones. Org. Lett 2019, 21, 567–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Karmakar R; Rheingold AL; Micalizio GC Studies Targeting Ryanodol Result in an Annulation Reaction for the Synthesis of a Variety of Fused Carbocycles. Org. Lett 2019, 21, 6126–6129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zhang X; Lu Z; Fu C; Ma S Synthesis of Highly Substituted Allylic Alcohols by a Regio- and Stereo-defined CuCl-mediated Carbometallation Reaction of 3-aryl-substituted Secondary Propargylic Alcohols with Grignard Reagents, Org. Biomol. Chem 2009, 7, 3258–3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Achmatowicz O Jr.; Bukowski P; Szechner B; Zwierzchowska Z; Zamojski A Synthesis of Methyl 2,3-Dideoxy-DL-Alk-2-Enopyranosides from Furan Compounds, Tetrahedron, 1971, 27, 1973–1996. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Osborn JA; Jardine FH; Young JF; Wilkinson G The Preparation and Properties of Tris(triphenylphosphine)halogenorhodium(I) and Some Reactions thereof including Catalytic Homogeneous Hydrogenation of Olefins and Acetylenes and their Derivatives. J. Chem. Soc. A 1966, 1711–1732. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sonogashira K; Tohda Y; Hagihara N A Convenient Synthesis of Acetylenes: Catalytic Substitutions of Acetylenic Hydrogen with Bromoalkenes, Iodoarenes, and Bromopyridines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975, 16, 4467–4470. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Milstein D; Stille JK Palladium-Catalyzed Coupling of Tetraorganotin Compounds with Aryl and Benzyl halides. Synthetic Utility and Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101, 4992–4998. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Oikawa Y; Yoshioka T; Yonemitsu O Specific Removal of O-Methoxybenzyl Protection by DDQ Oxidation. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982, 23, 885–888. [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Grieco PA; Gilman S; Nishizawa M Organoselenium Chemistry. A Facile One-Step Synthesis of Alkyl Aryl Selenides from Alcohols. J. Org. Chem 1976, 41, 1485–1486. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sharpless KB; Young MW Olefin Synthesis. Rate Enhancement of the Elimination of Alkyl Aryl Selenoxides by Electron-Withdrawing Substitutents. J. Org. Chem 1975, 40, 947–949. [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Scheidt KA; Chen H; Follows BC; Chemler SR; Coffey DS; Roush WR Tris(dimethylamino)sulfonium Difluorotrimethylsilicate, a Mild Reagent for the Removal of Silicon Protecting Groups. J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 6436–6437. [Google Scholar]; (b) Noyori R; Nishida I; Sakata J; Nishizawa M Tris(dialkylamino)sulfonium Enolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 1223–1225. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Griffith WP; Ley SV; Whitcombe GP; White AD Preparation and Use of Tetra-n-butylammonium Per-ruthenate (TBAP reagent) and Tetra-n-propylammonium Per-ruthenate (TPAP reagent) as New Catalytic Oxidants for Alcohols. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun 1987, 1625–1627. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Hanson RM Epoxide Migration (Payne Rearrangement) and Related Reactions. Org. React 2002, 60, 1–156. [Google Scholar]

- (20). While it was appreciated that epoxy alcohols can be isomerized through Payne rearrangement by exposure to base, attempted base-mediated equilibration of 18 proved unsuccessful, providing a complex product mixture.

- (21).For an alternative means of generating 1,2-cyclopropanediols from 1,3-diketones, see:; Armand J; Boulares L Electrochemical reduction of 1,3-Diketones in Hydroorganic Medium. Preparation of 1,2-cyclopropanediols. Can. J. Chem 1976, 54, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Garber SB; Kingsbury JS; Gray BL; Hoveyda AH Efficient and Recyclable Monomeric and Dendritic Ru-Based Metathesis Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 8168–8179. [Google Scholar]

- (23).(a) Gansäuer A; Bluhm H; Pierobon M Emergence of a Novel Catalytic Radical Reaction: Titanocene-Catalyzed Reductive Opening of Epoxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 12849–12859. [Google Scholar]; (b) Obradors C; Martinez RM; Shenvi RA Ph(i-PrO)SiH2: An Exceptional Reductant for Metal-Catalyzed Hydrongen Atom Transfers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 4962–4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kanda Y; Nakamura H; Umemiya S; Puthukanoori RK; Appala VRM; Gaddamanugu GK; Paraselli BR; Baran PS Two-Phase Synthesis of Taxol®, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 10526–10533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.