Abstract

Objective

The premise of the NIMH RAISE-ETP (Early Treatment Program) is to combine state-of-the-art pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments delivered by a well-trained, multidisciplinary team, in order to significantly improve the functional outcome and quality of life for first episode psychosis patients. The study is being conducted in non-academic (“real world’) treatment settings, using primarily extant reimbursement mechanisms.

Method

We developed a treatment model and training program based on extensive literature review and expert consultation. Our primary aim is to compare the experimental intervention to “usual care” on quality of life. Secondary aims include comparisons on remission, recovery and cost effectiveness. Patients 15–40 years old with a first episode of schizophrenia; schizoaffective disorder; schizophreniform disorder, psychotic disorder NOS, or brief psychotic disorder according to DSM IV and no more than six months of antipsychotic medications were eligible. Patients are followed for a minimum of two years, with major assessments conducted by blinded, centralized raters using live, two-way video. We selected 34 clinical sites in 21 states and utilized cluster randomization to assign 17 to the experimental treatment and 17 to usual care. Enrollment began in July, 2009 and ended in July 2011 with 404 subjects. The results of the trial will be published separately. The goal of the paper is to present both the overall development of the intervention and the design of the clinical trial to evaluate its effectiveness.

Conclusion

We believe that we have succeeded in both designing a multimodal treatment intervention that can be delivered in real world clinical settings and implementing a controlled clinical trial which can provide the necessary outcome data to determine its impact on the trajectory of early phase schizophrenia.

I. Introduction

Psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia are associated with enormous personal suffering, disability, family burden and societal cost. The course is most often chronic and recovery rates have been disappointingly low1,2. Several single element interventions (e.g. pharmacotherapy3, cognitive behavior therapy4, family work5 and supported employment6) have been shown to be effective at least over the short term. Although a number of innovative and integrated first episode programs have been implemented7,8,9,10,11 there are remarkably few prospective, randomized controlled trials comparing a multimodal multidisciplinary team approach to usual care12,13,14,15,16. Such a study has never been conducted in the U.S. in real world community clinics under extant reimbursement constraints. Even though academic centers play a key role in developing and testing new treatment strategies, unless such strategies can be implemented in typical, non-academic settings, it would be difficult to provide the necessary access and sustainability for the general population across the U.S.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) issued a Request for Proposals entitled “Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE)” in November 2007. The goal of the NIMH initiative is to change the trajectory and prognosis of first episode psychosis (FEP). The premise is that by combining state-of-the-art pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments in a patient-centric fashion and having them delivered by a well-trained and coordinated, multidisciplinary team, the functional outcome and quality of life for first episode patients treated in the community can be significantly improved17,18. The specified aims of RAISE are, first, to develop a comprehensive and integrated intervention designed to: promote symptomatic recovery; minimize disability; maximize social, academic and vocational functioning; be capable of being delivered in real world settings utilizing current funding mechanisms, and, second, to assess the overall clinical impact and cost effectiveness of the intervention as compared to currently prevailing treatment approaches and to conduct the comparison in non-academic, real world community treatment settings in the U.S.

In order to respond to NIMH’s requirements and achieve the desired goals, we assembled a leadership group representing expertise in early intervention and detection, psychosocial treatment, psychopharmacology, clinical trials, health economics, health policy, biostatistics, medical anthropology and service system administration. In addition, we consulted with a range of experts including, consumers, family members, advocacy groups and state and governmental officials. As this was funded via a contract mechanism, there was a close collaboration between the study researchers and NIMH colleagues with respect to study design, implementation and oversight. The contract was awarded in July 2009, bolstered by funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

In this report we provide a description of the overall design of the research project, the RAISE Early Treatment Program (RAISE-ETP), and a discussion of the rationale for certain key decisions including site selection, randomization strategy and approach to assessment and analysis. The goal was to develop a treatment model and training program that would allow us to engage a broad range of clinics across the U.S. without prior experience or specialized programs for FEP patients. We also sought a diverse group of sites from both a geographic and demographic perspective, so that the results would be as generalizable as possible. Ultimately, an important objective is to provide data-driven recommendations to the NIMH, health care policy makers, payers and other stakeholders on how care for individuals experiencing a first episode should be delivered.

II. Methods

a. Specific Aims

Our primary aim is to compare the impact of a multimodal, multidisciplinary team-based approach for FEP treatment to care usually delivered in community treatment settings (“usual care”) on quality of life, in a large, practical clinical trial. Secondary aims include comparisons with regard to remission, recovery and cost-effectiveness.

b. Subjects

Inclusion criteria were: 1) between 15–40 years of age; 2) ability to participate in research assessments in English; 3) ability to provide fully informed consent (assent for those under 18); 4) presence of definite psychotic symptoms and evidence that one of the following is included in the differential diagnosis: schizophrenia; schizoaffective disorder; schizophreniform disorder, psychotic disorder NOS, or brief psychotic disorder (according to DSM-IV)19. Exclusion criteria were kept to a minimum: patients who had clearly experienced more than one discrete psychotic episode; substance-induced psychotic disorder; and current neurological disorder or psychiatric disorder due to a general medical condition. In order to achieve a practical balance between proximity to first treatment with antipsychotic medication and feasibility to recruit an adequate sample with the budget available, we allowed patients with up to six months of cumulative exposure to antipsychotic medications to enter the trial. Subjects were recruited from inpatient and outpatient facilities.

All subjects aged 18 years or older were required to provide written informed consent for study participation. Subjects under 18 provided written assent and their parents/guardians written consent. The study was conducted under the guidance of the Institutional Review Boards of the coordinating center and of the sites.

c. Site Selection

A critical early decision was whether to engage established community clinics and work with their existing personnel, or to establish a smaller number of new “specialty” FEP treatment centers designed specifically for this purpose and with personnel recruited especially for this project. We concluded that a program which could succeed across a range of diverse, existing community clinics and which included a broad representation of clinicians already working in such clinics who could be successfully trained by our team to deliver the enhanced intervention, would provide generalizable information and be useful in establishing a national model that fits with the way healthcare is currently delivered and reimbursed in the U.S. In some locales specialized clinics might be an appropriate alternative based on geographic and population density opportunities; however, we believe that a major treatment need for FEP patients is to have appropriate care in readily accessible community clinics. The decision to conduct the project in community clinics had enormous implications for the development of our treatment and training model, as well as for how the trial would be conducted.

We, therefore, sought a representative group of sites that (based on our evaluation) appeared capable of implementing the program and the study evaluation protocol while also recruiting the necessary number of FEP subjects. Sites with existing first episode treatment programs were excluded. Via advertising, personal contacts and outreach to The National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, the NIMH Schizophrenia Trials Network, The National Council for Behavioral Health and other organizations, we announced the opportunity for sites to participate in the project. Of the 79 potential sites that expressed interest in participation 63 completed a detailed questionnaire about the populations that they served and their ability to provide study treatment (including all psychosocial treatments and recommended pharmacological therapies) and support study assessments.

Questionnaire responses were reviewed by the study site selection committee; this review was followed by a telephone conference with the site. A site selection committee member visited all sites that remained potentials after the telephone conference and before final selection by the committee. Besides site capacity to perform the trial, geographic and demographic diversity was also considered in the selection process. Thirty-five sites were selected.

d. Interventions

The intervention was developed following an extensive literature review and consultation with appropriate experts in the U.S and abroad. (A detailed description of the intervention is beyond the scope of this report and will be published separately.) Manuals designed for training in each component are now available online at www.raiseetp.org. We named our enhanced treatment program “NAVIGATE” in order to convey in an optimistic fashion its mission of helping individuals with a first episode of psychosis (and their families) in finding their way towards psychological and functional well-being, and to accessing the services they need in the mental health system. The core interventions provided by the NAVIGATE clinical team include: individualized medication management assisted by a computerized decision support system for the prescriber (the secure web-based program named COMPASS was developed by us specifically for this project); family education; individual resiliency training; and supported education and employment. The coordinated implementation of the NAVIGATE program requires an approach to treatment that is shared by all team members. This includes: shared decision-making, strengths and resiliency focus, recognition of the need for motivational enhancement, a psycho-educational approach, cognitive behavior therapy methods, and collaboration with natural supports. Regular team meetings are essential.

The control condition was designated “Community Care” and represented the routine treatment offered by that clinic for such patients without any additional training or supervision provided by the central team, except in relationship to retention in the research assessment and follow up component.

e. Study Design and Implementation

i. Randomization

The study employed a cluster randomization design – that is randomization by clinic/site rather than individual patient. This decision was based on a number of critical factors. Patient randomization would have required each site to have a specialized, separate, systematically trained and supervised team to manage those patients randomized to the NAVIGATE intervention, while maintaining a different group of clinicians to offer usual care to those randomized to the comparison condition. This would present challenges in terms of both establishing a viable NAVIGATE program with only half the recruited patients being assigned to it, and minimizing the risk of potential “spillover” or “contamination” effects when patients are assigned to two different “open” treatments within the same clinic. Further, community sites would rarely be able to staff separate study teams. An additional advantage of cluster randomization is that individuals do not have to agree to randomization, but only have to consent to participating in a study where they will receive the treatment provided in their setting, and to understand to which treatment condition the site has been randomized.

There are, however, risks associated with site randomization. One major risk is that cluster randomization will not be successful and that there will be systematic differences between the intervention and usual care sites and/or patients. However, with a sufficient number of sites, adjustments can be made in the statistical analysis for imbalances through measured covariates, allowing a valid comparison of the interventions. Given the practical advantages of site randomization, and the ability to make statistical adjustments if needed, we concluded that randomization at the level of site rather than patient was scientifically optimal. This was acceptable to sites, and none withdrew following randomization.

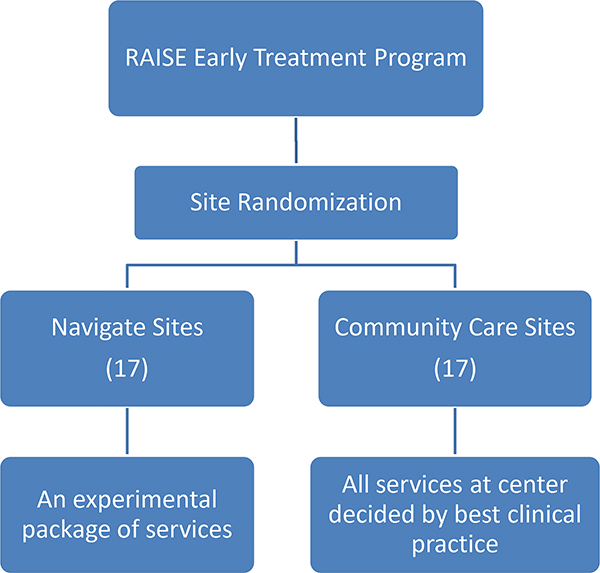

Thirty-five sites were randomized to either NAVIGATE or the Community Care condition. Following randomization and initial training, two of the sites were dropped from the trial before any subjects had been entered because they were unable to recruit. One site was subsequently added, resulting in 34 sites (17 in each treatment condition). Figure 1 shows site locations; the study included 21 of the 48 contiguous states. The study design of the RAISE-ETP Program is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Map of Sites

Figure 2.

Study Design

ii. Research Infrastructure

RAISE-ETP funded staffing for the research portion of the program at all sites: a part time Study Director and Research Assistant to recruit, coordinate and assess study subjects. All sites met together for an initial project meeting and orientation to overall study goals and research procedures. Once the study teams returned home, they learned whether they had been randomized to NAVIGATE or Community Care. Those assigned to NAVIGATE next received initial training in the multi-modal, team-based intervention and on-going consultation and support. A procedure was in place to assess competence and monitor fidelity in the delivery of all components of the NAVIGATE intervention. A full description of these procedures is beyond the scope of this communication and is the focus of another report. Our clinical strategies for managing attrition at all sites include ongoing contact with sites to support their efforts to keep subjects in both treatment and assessment and a progressive subject reimbursement schedule that recognizes the importance of participation in assessments over time as allowed by the Institutional Review Boards.

iii. Trial Duration

The trial was designed to provide a minimum of two years of study treatment; subjects who entered early in the enrollment phase may have treatment for up to 43 months. During this initial study treatment phase, patients could choose to continue to participate in research outcome assessments even if they were no longer receiving treatment in the NAVIGATE program or in Community Care. Treatment was allowed to be intermittent, if necessary, and patients were welcome to return to the treatment even after lengthy interruptions for whatever reason (personal choice, incarceration, etc.) No threshold was in place for discontinuing patients from the trial. The study also includes a long-term follow-up phase; assessments continue for five years after subjects’ study treatment began.

iv. Assessment Strategy and Schedule

Because site-based personnel were not blind to treatment, the assessment strategy combined site-based and centralized assessments. The site-based assessments were conducted by research assistants (RAs) who were trained to complete their assigned assessments, but were not required to have sufficient clinical background or the training necessary to administer research quality assessments. A major challenge in conducting, multisite studies at non-academic, community clinics is ensuring the availability of well-trained, calibrated interviewers/raters at each site. In addition, when a study involves different psychosocial treatment conditions, maintaining “blinded” assessment is very difficult. Therefore, remote, centralized personnel provided by MedAvante carried out diagnosis/assessment utilizing live, two-way video. The centralized assessments were conducted by individuals with sufficient clinical experience and sufficient training to provide research quality diagnostic interviews and ongoing outcome assessments for psychopathology and quality of life – while remaining blind to treatment assignment and to the overall study design. Diagnosis (utilizing the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-SCID19); duration of untreated psychosis; the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)20; Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale21; the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS)22; and the Quality of Life Scale (QLS)23, our primary functional outcome measure, were administered by the centralized raters. As shown in Table 1, the SCID19 was completed at baseline and at the one-year assessment; other measures were completed every six months. Remote assessment utilizing two-way video has been shown to be comparable to face-to-face assessments in patient acceptability and reliability28,29,30. The remaining assessments were conducted by site-based personnel. Our primary tool for assessing cost of services is the Service Use and Resource Form (SURF)24 completed monthly, that documents all inpatient, residential, Emergency department, and outpatient mental health and medical services used in the past month. At less frequent intervals, insurance coverage information is collected as well. The SURF has been used in several previous multi-site clinical trials of both pharmaceutical and psychosocial interventions31 and is not influenced by the mix of payors. Subject reimbursement was provided for each assessment. Subjects are also assessed for the presence of 21 antipsychotic side effects (side effects were chosen for assessment based upon a review of the frequency of occurrence reported in first episode medication trials-See Table 1)

Table 1.

Assessment Measures

| Assessment Schedule | |||||||||||||||

| Year 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Month | Screen | BL1/0 | BL2/0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| PROCEDURE | |||||||||||||||

| On-Site Assessments | |||||||||||||||

| IRB-approved Informed Consent Form | X | ||||||||||||||

| Screening Form (In-/Exclusion) | X | ||||||||||||||

| Demographics and Psychiatric History | X | ||||||||||||||

| Medical History & Current Medication | X | ||||||||||||||

| SURF-Monthly24 | X | P | P | X | P | P | X | P | P | P | P | P | X | ||

| SURF-Quarterly | X | X | X | P | X | ||||||||||

| Antipsychotic Medication Adherence Assessment | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Prescription Medication Experience | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Self-Report Assessment Form | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Annual Demographic Update | X | ||||||||||||||

| Intent to Attend Form25 | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Family Assessment Scale | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Client Recovery Outcomes | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Physical Assessment (Sitting and standing blood pressure, sitting and standing pulse, Weight, BMI, Waist Circumference, temperature, EPS, akathisia, and abnormal involuntary movements) | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Cognition BACS26 | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Laboratory Tests - lipid panel, metabolic profile, HbA1C and fasting insulin levels | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Urbanicity Questionnaire27 | X | ||||||||||||||

| Remote Telemedicine – | |||||||||||||||

| SCID – DSM-IV | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Psychopathology (PANSS/CGI/CDSS) | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Functional Outcome (QLS) | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Year 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Month | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | |||

| PROCEDURE | |||||||||||||||

| On-Site Assessments | |||||||||||||||

| SURF-M | P | P | P | P | P | X | P | P | P | P | P | X | |||

| SURF-Q | P | X | P | X | |||||||||||

| Antipsychotic Medication Adherence Assessment | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Prescription Medication Experience | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Self-Report Rating Form | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Intent to Attend Form | X | ||||||||||||||

| Annual Demographic Update | X | ||||||||||||||

| Family Assessment Scale | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Client Recovery Outcomes | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Physical Assessment (Sitting and standing blood pressure, sitting and standing pulse, Weight, BMI, Waist Circumference, temperature, EPS, akathisia, and abnormal involuntary movements) | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Cognition (BACS) | X | ||||||||||||||

| Laboratory Tests - lipid panel, metabolic profile, HbA1C and fasting insulin levels | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Remote Telemedicine – SedAvante | |||||||||||||||

| Psychopathology (PANSS/CGI/CDSS) | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Functional Outcome (QLS) | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Year 3 | |||||||||||||||

| Month | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | |||

| PROCEDURE | |||||||||||||||

| On-Site Assessments | |||||||||||||||

| SURF-M | P | P | P | P | P | X | P | P | P | P | P | X | |||

| SURF-Q | P | X | P | X | |||||||||||

| Antipsychotic Medication Adherence Assessment | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Prescription Medication Experience | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Self-Report Rating Form | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Annual Demographic Update | X | ||||||||||||||

| Intent to Attend Form | X | ||||||||||||||

| Family Assessment Scale | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Client Recovery Outcomes | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Physical Assessment (Sitting and standing blood pressure, sitting and standing pulse, Weight, BMI, Waist Circumference, temperature, EPS, akathisia, and abnormal involuntary movements) | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Laboratory Tests - lipid panel, metabolic profile, HbA1C and fasting insulin levels | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Remote Telemedicine – MedAvante | |||||||||||||||

| Psychopathology (PANSS/CGI/CDSS) | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Functional Outcome (QLS) | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Year 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Month | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | |||

| PROCEDURE | |||||||||||||||

| On-Site Assessments | |||||||||||||||

| SURF-M | P1 | P1 | P1 | P1 | P1 | X | P1 | P1 | P1 | P1 | P1 | X | |||

| SURF-Q | P1 | X | P1 | X | |||||||||||

| Antipsychotic Medication Adherence Assessment | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Prescription Medication Experience | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Self-Report Rating Form | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Annual Demographic Update | X | ||||||||||||||

| Intent to Attend Form | X | ||||||||||||||

| Family Assessment Scale | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Client Recovery Outcomes | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Physical Assessment (Sitting and standing blood pressure, sitting and standing pulse, Weight, BMI, Waist Circumference, temperature, EPS, akathisia, and abnormal involuntary movements)1 | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Laboratory Tests - lipid panel, metabolic profile, HbA1C and fasting insulin levels1 | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Remote Telemedicine – MedAvante | |||||||||||||||

| Psychopathology (PANSS/CGI/CDSS) | X | X2 | |||||||||||||

| Functional Outcome (QLS) | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Year 5 | |||||||||||||||

| Month | 54 | 60 | |||||||||||||

| PROCEDURE | |||||||||||||||

| On-Site Assessments | |||||||||||||||

| SURF-M | X | X | |||||||||||||

| SURF-Q | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Client Status Update | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Physical Assessment (Sitting and standing blood pressure, sitting and standing pulse, Weight, BMI, Waist Circumference, temperature, EPS, akathisia, and abnormal involuntary movements)1 | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Laboratory Tests - lipid panel, metabolic profile, HbA1C and fasting insulin levels1 | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Remote Telemedicine –Assessments | |||||||||||||||

| Psychopathology (PANSS) | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Functional Outcome (QLS) | X | X | |||||||||||||

P= Phone Interview; X=In person Assessment; AIM = Abnormal Involuntary Movements; BACS= Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; CDSS=Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; CGI=Clinical Global Impressions; EPS = Extrapyramidal symptoms; PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; QLS=Quality of Life Scale; SCID=Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders; SURF-M and Q =Service Utilization and Resources Form for Schizophrenia

P= Phone Interviews; X=In person Interviews; AIM= Abnormal Involuntary Movements; BACS= Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; BARS=Brief Adherence Rating Scale; CDSS=Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; EPS= Extrapyramidal symptoms; CGI=Clinical Global Impressions; PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; QLS=Quality of Life Scale; SURF-M and Q =Service Utilization and Resources Form for Schizophrenia

P= Phone Interviews; X=In person Interviews; AIM= Abnormal Involuntary Movements; BACS= Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; BARS=Brief Adherence Rating Scale; CDSS=Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; EPS= Extrapyramidal symptoms; CGI=Clinical Global Impressions; PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; QLS=Quality of Life Scale; SURF-M and Q =Service Utilization and Resources Form for Schizophrenia

P= Phone Interviews; X=In person Interviews; AIM= Abnormal Involuntary Movements; BACS= Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; BARS=Brief Adherence Rating Scale; CDSS=Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; EPS= Extrapyramidal symptoms; CGI=Clinical Global Impressions; PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; QLS=Quality of Life Scale; SURF-M and Q =Service Utilization and Resources Form for Schizophrenia

=Data only collected for a subset of participants

=PANSS only

P= Phone Interviews; X=In person Interviews; PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; QLS=Quality of Life Scale; SURF-M and Q =Service Utilization and Resources Form for Schizophrenia

= Data only collected for a subset of participants

v. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Data management is conducted by Innovative Clinical Research Solutions at The Nathan Kline Institute. The analysis of the primary outcome will compare the treatment differences in the overall quality of life (Total QLS score) and over time during the first two years (baseline, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months). A three level nested mixed-effects linear model (32,33) will include a fixed effect for the treatment indicator, terms of time, and their interactions, and a random intercept at the patient-level and a random intercept at the site level. The terms of time are coded as different levels of the categorical time. The effect of the interactions between the treatment and the terms of time will be tested for the treatment difference in overall functional outcome. Treatment difference will be declared if the interaction terms are statistically significant with four degrees of freedom at two-tailed alpha-level of 0.05. To test the rate of improvement in QLS between the two intervention groups over the course of the treatment (difference in slope), time will be used as a numerical variable and the interaction term with one degree of freedom will be tested. In addition, the model fit with a first-order autoregressive (AR1) covariance structure will be tested against the independent structure (34). Likelihood ratio tests will be used in all tests. Sample size requirements for mixed-effects linear regression analyses were based on RMASS (34). We assumed that the intra class correlation (ICC) within subject will range from .30 to .60 and the ICC within site is 0.10. We have at least N=145 per group, even after accounting for 20% attrition, the proposed design will provide power in excess of 0.90 to detect an overall group difference and the difference in rate of change over time for a standardized effect size at the 24 month visit as small as 0.40 sd units. We consider a difference of this magnitude, which represents 9 points of the QLS scale, clinically meaningful. Thus, given the assumptions, the sample size should provide sufficient power to test our primary hypothesis regarding quality of life.

Summary and Conclusions

The project was initiated on July 13, 2009 and completed enrollment of the 404 subjects in July, 2011. We believe that we have succeeded in both designing a multimodal treatment intervention that can be delivered in “real world” clinical settings under extant reimbursement constraints and implementing a randomized, controlled clinical trial which can provide the necessary outcome data to determine its impact on the trajectory of early phase schizophrenia. We are very grateful for the help of numerous consultants and advisors, the outstanding participation of our core collaborators and the terrific efforts of all of the treatment teams at the 34 participating sites. We also extend our thanks to all of the patients and families who have agreed to work with us in this effort.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Points.

Functional recovery rates among patients with schizophrenia need to be improved substantially.

A number of innovative and integrated first episode programs have been implemented around the world.

The premise of the RAISE ETP project is that by combining state-of-the-art pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments, delivered by a well-trained, coordinated multidisciplinary team functional outcome and quality of life can be significantly improved.

Acknowledgement

We thank the participating patients and their families, each of the participating 34 centers and their personnel (see Appendix 1)

Funding:

Funding for this study was supported by a contract from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Bethesda, MD (HHSN-271-2009-00019C, Dr. Kane). In addition, this project has also been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN271200900019C. Additional support for the design of this project was provided by an ACISR award (P30MH090590Kane) from NIMH. The NIMH had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures

Drs. Mueser, Estroff, J Robinson, Penn have nothing to disclose.

Dr. Brunette has received grant support from The National Cancer Institute

Dr. Correll has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: Actelion, Alexza; Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Gerson Lehrman Group, IntraCellular Therapies, Lundbeck, Medavante, Medscape, Merck, National Institute of Mental Health, Janssen/J&J, Otsuka, Pfizer, ProPhase, Roche, Supernus, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and Vanda. He has received grant support from American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, BMS, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Janssen/J&J, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), Novo Nordisk A/S, Otsuka, Thrasher Foundation.

Dr. Kane has been a consultant for Alkermes, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals (Forum), Forest, Genentech, H. Lundbeck. Intracellular Therapeutics, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Johnson and Johnson, Otsuka, Reviva and Roche. Dr. Kane has been on the Speaker’s Bureau for Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Janssen, Genentech and Otsuka. Dr. Kane is a Shareholder in MedAvante, Inc.

Ms. Marcy is a shareholder of Pfizer

Dr. D. Robinson has been a consultant to Asubio and Shire, and he has received grants from Bristol Meyers Squibb, Janssen, and Otsuka.

Dr. Rosenheck has received research support from Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. He has been a consultant to Otsuka. He provided expert testimony for the plaintiffs in UFCW Local 1776 and Participating Employers Health and Welfare Fund, et al. v. Eli Lilly and Company; for the respondent in Eli Lilly Canada Inc vs Novapharm Ltd and Minister of Health; for the Patent Medicines Prices

Dr. Schooler has received grant/research support from Otsuka, Neurocrine, and Genentech. She has been on the speaker or advisory board to Lundbeck, Roche, Envivo (Forum) and Sunovion.

Trial Registration Number NCT01321177

Disclaimer: The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of National Institute of Mental Health or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- 1.Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, Mendelowitz A, Bilder RM: Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161: 473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaaskelainen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, McGrath JJ, Saha S, Isohanni M, Veijola J, Miettunen H. A systematic review and metaanalysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013:39(6): 1296–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Napolitano B, Patel RC, Sevy SM, Gunduz-Bruce H, Soto-Perello JM, Mendelowitz A, Khadivi A, Miller R, McCormack J, Lorell BS, Lesser ML, Schooler NR, & Kane JM Randomized comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone for the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia: 4-month outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12), 2096–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penn DL, Uzenoff SR, Perkins D, Mueser KT, Hamer R, Waldheter E, Saade S, Cook L. A pilot investigation of the Graduated Recovery Intervention Program (GRIP) for first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2011;125(2–3):247–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenior ME, Dingemans PM, Schene AH, Hart AA & Linszen DH The course of parental expressed emotion and psychotic episodes after family intervention in recent-onset schizophrenia. A longitudinal study. Schizophr Res. 2002;57:183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Killackey E1, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD. Vocational intervention in first-episode psychosis: individual placement and support v. treatment as usual. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(2):114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGorry PD, Edwards J, Mihalopoulos C, Harrigan SM, & Jackson HJ. EPPIC: An evolving system of early detection and optimal management. Schizophrenia Bulletin.1996;22,305–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullberg J, Levander S, Holmqvist R, Mattsson M, Wieselgren IM. One-year outcome in first episode psychosis patients in the Swedich Parachute project. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106: 276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malla AK, Norman RM, Manchanda R, Ahmed MR, Scholten D, Harricharan R, Cortese L, Takhar J. One year outcome in first episode psychosis: influence of DUP and other predictors. Schizophr Res. 2002;54(3):231–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Addington J, Leriger E, and Addington D. Symptom outcome one year after admission to an early psychosis program. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;48:204–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penn DL, Waldheter EJ, Perkins DO, Mueser KT, Lieberman JA. Psychosocial treatment for first-episode psychosis: r research update. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162, 2220–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, Abel MB, Ohlenschlaeger J, Christensen TO, Krarup G, Jorgensen P &Nordentoft, M. A randomized multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. BMJ.2005a; 331:602–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen L, Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Ohlenschaeger J, Thorup A, Christensen TO, Krarup G, Dahlstrom J, Haastrup B & Jorgensen P Improving 1-year outcome in first-episode psychosis: OPUS trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2005b. Suppl, 48, s98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Øhlenschlaeger J, le Quach P, Christensen TØ, Krarup G, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M.; Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness: the OPUS trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):762–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig TK, Garety P, Power P, Rahaman N, Colbert S, Fornells-Ambrojo M, Dunn G. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialized care for early psychosis. BMJ. 2004;329:1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sigrúnarson V, Gråwe RW, Morken G.. Integrated treatment vs. treatment-as-usual for recent onset schizophrenia; 12 year follow-up on a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birchwood M, Todd P, & Jackson C Early intervention in psychosis: The critical period hypothesis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;172 (Supplement 33), 53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertolote J, McGorry P. Early intervention and recovery for young people with early psychosis: Consensus statement. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187 (suppl 48), s116–s119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV® Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Clinician Version, Administration Booklet. American Psychiatric Pub. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guy W Clinical Global Impressions In ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology, revised (DHEW Publ No ADM 76–338. 1976;pp. 218–222. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E. Assessing depression in schizophrenia: The Calgary Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;163(Suppl 22): 39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr. The Quality of Life Scale An Instrument for Rating the Schizophrenic Deficit Syndrome. Schizophrenia Bulletin.1984;10(3):388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenheck RA, Kasprow W, Frisman LK, Liu-Mares W. Cost-effectiveness of Supported Housing for Homeless Persons with Mental Illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 2003;60:940–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leon Andrew C., Demirtas Hakan, and Hedeker Donald. “Bias reduction with an adjustment for participants’ intent to dropout of a randomized controlled clinical trial.” Clinical Trials 45 (2007): 540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keefe RSE, Harvey PD, Goldberg TE, Gold JM, Walker TM, Kennel C, Hawkins K. Norms and standardization of the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) Schizophrenia Research. 2008;102(1–3):108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haddad L, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Social environmental risk factors and mental disorders: insights into underlying neural mechanisms drawing on the example of urbanicity. Nervenarzt. 2012; 83(11):1403–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen J, Kobak KA, Zhao Y, Alexander MM, Kane JM. Use of remote centralized raters via live 2-way video in a multicenter clinical trial for schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology.2008;28(6):691–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zarate CA,Weinstock L, Cukor P, Morabito C, Leahy L, Burns C, Baer L. Applicability of telemedicine for assessing patients with schizophrenia: Acceptance and reliability. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1997; 58(1):22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowe M, Rosenheck R, Stern E, Bellamy C. Video Conferencing Technology in Research on Schizophrenia: A Qualitative Study of Site Research Staff. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processess. 2014;77(1),98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenheck RA, Leslie DL, Sindelar J, Miller EA, Lin H, Stroup TS, McEvoy J, Davis SM, Keefe RSE, Swartz M, Perkins DO, Hsiao JK, Lieberman JA. Cost-effectiveness of second generation antipsychotics and perphenazine in a randomized trial of treatment for chronic schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 2006, 163:2080–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ten Have TR, Localio AR. Empirical Bayes estimation of random effects parameters in mixed effects logistic regression models. Biometrics. 1999;55(4):1022–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein H Multilevel Statistical Models. 2011;4th ed London: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal Data Analysis. 2006. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.