Abstract

Objectives

Recruitment and retention in child and adolescent healthy lifestyle intervention services for childhood obesity is challenging, and inequalities across social groups are persistent. This study aimed to understand the barriers and facilitators to engagement in a multicomponent assessment-and-intervention healthy lifestyle programme for children and their families, based in the home and community.

Design

Qualitative interview-based study of past users (n=76) of a family-based multicomponent healthy lifestyle programme in a mixed urban–rural region of New Zealand. Semistructured, home-based interviews were conducted and thematically analysed with peer debriefing for validity.

Participants

Families were selected through stratified random sampling to include a range of levels of engagement, including those who declined their referral, with equal numbers of interviews with Indigenous and non-Indigenous families.

Results

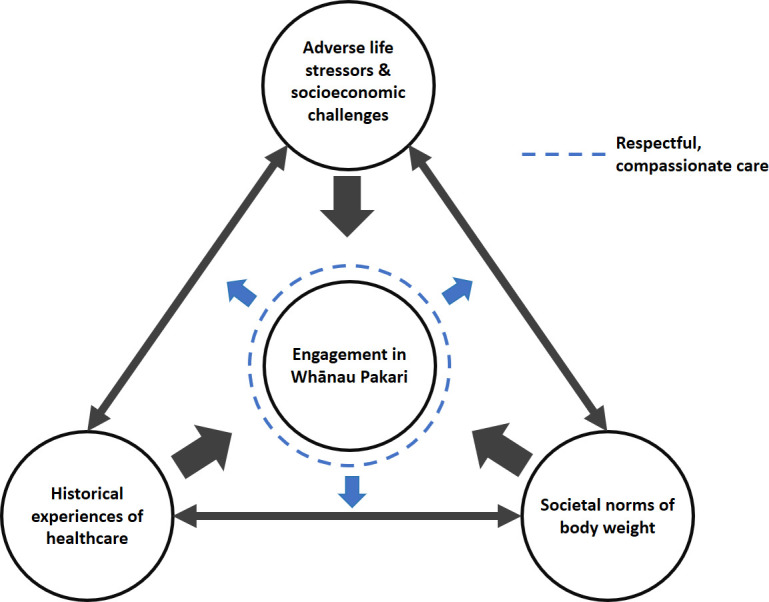

Three interactive and compounding determinants were identified as influencing engagement in Whānau Pakari: acute and chronic life stressors, societal norms of weight and body size and historical experiences of healthcare. These determinants were present across societal, system and healthcare service levels. A negative referral experience to Whānau Pakari often resulted in participants declining further input or disengaging from the programme. A fourth domain, respectful and compassionate healthcare, was identified as a mitigator of these three themes, facilitating participant engagement despite previous negative experiences.

Conclusions

While participant engagement in healthy lifestyle programmes is affected by determinants which appear to operate outside immediate service provision, the programme is an opportunity to acknowledge past instances of stigma and the wider challenges of healthy lifestyle change. The experience of the referral to Whānau Pakari is important for setting the scene for future engagement in the programme. Respectful, compassionate care is critical to enhanced retention in multidisciplinary healthy lifestyle programmes and ongoing engagement in healthcare services overall.

Keywords: paediatrics, community child health, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large sample size (64 interviews with 76 total participants).

Sample included wide range of participants with varying levels of engagement, including non-service users.

Equal representation from families with Māori and non-Māori children.

Lack of child and adolescent voice.

Participants may not have fully disclosed their experiences to interviewers.

Introduction

Excess weight in childhood and adolescence affects physical, psychological and social health and well-being, and is a known risk factor for comorbidities both in childhood and adulthood.1 Children with weight issues in Aotearoa/New Zealand (henceforth, referred to as New Zealand (NZ)) demonstrate a high prevalence of weight-related comorbidities, as well as low physical activity, suboptimal eating behaviours and low health-related quality of life.2–5 One of the key recommendations of the WHO’s Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity is to ‘provide family-based, multicomponent lifestyle weight management services for children and young people who are obese’.6 A systematic review and meta-analysis found that a minimum of 26 hours of contact time in lifestyle interventions is associated with improvements in weight status in children and adolescents.7 However, as with any service attempting to facilitate lifestyle change, success relies on continued family engagement.8 It is also important that such multidisciplinary services—and other health professionals addressing childhood obesity in a primary care setting—are able to engage with groups most affected by obesity, namely those living in the most deprived areas and ethnic minorities.9

Improving engagement with childhood obesity services requires addressing both initial recruitment and ongoing retention.8 Service, system and society-related factors may enable or inhibit initial and ongoing engagement; factors which are also referred to as facilitators and barriers.10 11 Kelleher and colleagues’ review of the factors affecting attendance at community-based lifestyle programmes found that weight stigma, parental reluctance to identify overweight and logistical challenges were key barriers to initial and ongoing attendance.10 Under-represented in the literature are those who declined treatment altogether, as many past studies had low recruitment from these families. It is therefore important to understand the experiences of families experiencing childhood obesity in order to improve initial recruitment and ongoing retention in healthy lifestyle services, particularly for groups most affected.10

Whānau Pakari is a family-centred, community-based assessment and intervention programme for children and their families, based in Taranaki, a mixed urban–rural region of NZ. The name means ‘healthy, self-assured families that are fully active’. The focus of the programme is on healthy lifestyle change rather than weight loss or obesity, in order to minimise judgement and weight-related stigma. The multidisciplinary service involves a home-based medical assessment with advice, removing the hospital appointment in order to demedicalise care, and includes weekly nutrition, physical activity and psychology sessions. This approach takes healthcare outside hospital walls and into the community, without compromising quality of care. A randomised clinical trial of the Whānau Pakari model of care demonstrated modest reductions in body mass index (BMI) SD score (SDS) and improvements in cardiovascular fitness and health-related quality of life.12 13 Greatest improvements in BMI SDS were found in those who attended the recommended ≥70% of intense intervention sessions.13 14 However, Māori (NZ’s Indigenous population) and females were less likely to attend ≥70% of sessions, with sustained retention in the programme favouring males and NZ Europeans.13

Previous evaluation of the experiences of Whānau Pakari participants and their caregivers has shown the programme to be a positive and beneficial experience for those involved, emphasising the importance of connectedness, knowledge-sharing and self-determination, the collective journey alongside other families and programme deliverers, and the importance of a non-judgemental, respectful environment.15 A survey of past participants of Whānau Pakari indicated that previous experiences of healthcare may influence subsequent engagement with health services, particularly for Māori,16 although this was not elaborated on further by participants. These findings were limited by the survey’s relatively small sample size and the lack of representation from participants who declined intervention. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to understand barriers and facilitators to initial attendance and ongoing retention in the Whānau Pakari programme.

Methods

Design

In NZ, health research is required to be responsive to the needs and diversity of Māori.17 The study design and research approach was informed by Kaupapa Māori methodological principles. Kaupapa Māori theory is a methodology which resists persistent power imbalances and the continued use of cultural deficit theory (attributing poor health to something inherent to a ‘culture’) to explain inequities between Māori and non-Māori,17 18 and is aligned with a social and structural determinants of health framework.19 As a methodological approach, Kaupapa Māori research centres Māori voice and experience, and prioritises understanding people within their contexts and whānau (families).19 It was hoped that this approach would reduce many of the known barriers to research participation for Indigenous peoples, and enable participants to engage positively in the research process.20 While Kaupapa Māori research can use both quantitative and qualitative methods, in this study, a qualitative research design was chosen in order to ensure that priority was given to ensuring the voices and experiences of Māori participants were understood in this study.

In-depth interviews, centring on participant experience with Whānau Pakari and wider experiences of the health system, were undertaken. A specific focus was to understand the barriers to attendance and retention at varying levels of engagement in Whānau Pakari, including those who declined their referral and had no further contact with the programme. Factors which facilitated both initial and ongoing engagement were explored.

Patient and public involvement statement

Participants were first involved in the research at the recruitment stage, although some participants had been involved in an earlier related randomised clinical trial.12 The research questions were informed by the experiences of participants voiced, unsolicited, during clinical assessment during the previous trial and in previous focus group research.15 The design of the research drew from Kaupapa Māori theory, which informed the research process in order to prioritise the experiences and preferences of participants. The dissemination process to participants was altered as a result of participant preference to receive feedback via a summary video, rather than at a group meeting. Participants were not asked to assess the burden of the time required to participate in the research.

Participants

Eligible participants were parents and/or caregivers of children and adolescents who had been referred to the service from January 2012 to January 2017. Children and adolescents over 11 years of age were also invited to participate. The eligibility criteria for referral to the service are children aged 4–16 years, identified as having obesity (BMI ≥98th centile), or overweight (BMI >91st centile) with associated weight-related comorbidities.12 21

Participants were recruited from four different groups of Whānau Pakari service users who had varying levels of engagement (table 1) using stratified random sampling. Recruitment was via telephone call and text message. The sample contained equal numbers of families with Māori and non-Māori children to ensure appropriate representation of Indigenous children’s experiences.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Interview participants, N | 76* | |

| Female participant, n | 65 | |

| Ethnicity, %† | Māori | 32 |

| NZ European | 75 | |

| Asian | 7 | |

| Other European | 5 | |

| Level of engagement, n | Attended ≥70% of programme sessions‡ | 18 |

| Attended <30% of programme sessions§ | 19 | |

| Had one assessment, then discontinued with the programme¶ | 7 | |

| Referred, but chose not to engage** | 20 |

*64 interviews total, 11 interviews involved 2+ family members, 5 interviews included a child/adolescent participant in addition to their parent/caregiver. Maximum total of 74 potential interviews for funding and resource reasons. 136 families approached, of which 53 were uncontactable, 7 were living out of the region and 12 declined (see Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist for reasons).

†Total ethnicity output (more than one ethnicity selected).

‡24 families invited total.

§42 families invited total.

¶15 families invited total.

**55 families invited total.

Data collection

The semi-structured interviews were approximately 30–60 min in duration and conducted by CEKW and NTR together where possible (see online supplemental appendix 2 for interview schedule). NTR led the interviews with Māori families when appropriate. Interviews took place in the participant home or alternative locations chosen by the participant (including a hospital, participant workplaces and a community library) in order to minimise inconvenience and travel barriers. Most interviews were undertaken with one participant (the parent or caregiver) but a portion included two or more family members, including children (table 1). A koha (gift, donation or contribution) was offered to participants in acknowledgement of their time and as a sign of reciprocity for the information shared.

bmjopen-2020-037152supp002.pdf (106.4KB, pdf)

Informed consent (or assent with proxy parental consent in the case of the child and adolescent participants aged under 16 years) was obtained to record, transcribe and analyse participant data. All participant information was anonymised. Participant ethnicity for both the parent/caregiver and child was confirmed at the time of the interview by using the NZ Census 2006 ethnicity question.22 All interviews were audio-recorded and independently transcribed. Participants were offered their transcripts to review for accuracy and acceptability.

Analysis

Interview transcripts were coded and analysed inductively in MAXQDA,23 according to Braun and Clarke’s method for reflexive thematic analysis,24 25 which aligned well with the reflexivity and awareness of researcher theoretical positioning required of research informed by Kaupapa Māori Theory. CEKW developed the coding matrix with peer review from EJW, coded the interview data, and identified the initial themes. The authors collaborated to finalise the themes and develop the framework. The acknowledgement of different researcher standpoints allowed the authors to debate, challenge and refine interpretations of the data, thereby developing a more nuanced interpretation of the data.25 Specifically, the researchers agreed to apply the ‘Give-Way’ rule if there was disagreement over the interpretation of the data concerning Māori participants, with the final decision involving cultural interpretation of Māori participants’ experiences passing to a Māori researcher.19 26 27

It became clear from our initial appraisal of the data that the degree to which participants engaged with the programme was on a continuum rather than fitting neatly into discrete categories. Therefore, the groups have been analysed together, noting where there may be key differences according to the degree of engagement.

For more detail of this procedure, refer to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (online supplemental appendix 1).

bmjopen-2020-037152supp001.pdf (101.4KB, pdf)

Results

64 interviews were conducted (out of a potential cohort of 74) with families who had varying levels of engagement, across a 6-month period from June to November 2018 (76 participants in total) (table 1). Half of the interviews were with Māori families (families with a Māori child who had been referred to the service), including interviews with non-Māori parents of Māori children. Participants included parents, grandparents, other caregivers and the children/adolescents themselves (n=5) and were from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds (deciles 1–10 of the 2013 NZ Index of Deprivation).28 Full details of interview recruitment rate and reasons for non-participation are included in the COREQ checklist (online supplemental appendix 1).

Three major interacting domains and subthemes affecting participant engagement are described in box 1 in participants’ own words. A fourth domain of respectful, compassionate care was identified as a mediator, which was able to partially mitigate the effect of the first three themes. Unique themes according to level of engagement with the programme were not generated. While each domain was prevalent in participant accounts across all recruitment categories, the extent to which a domain affected each group determined engagement.

Box 1. Key determinants of engagement and retention in Whānau Pakari.

Domain 1: adverse life stressors and socioeconomic deprivation

‘I wouldn’t say it was, like, you guys as such—it was just the history behind what she had um, but we come from, so um I came from an abusive marriage, which had split up because of abuse … So this was really hard at the time’.

‘Once she lost her father, well that was pretty much the end of it. She just didn’t want to do nothing. As much as I tried to encourage her to, you know, get with the programme, no she just didn’t want to know about it’.

Competing health priorities

‘… (DAUGHTER] was under [child and adolescent mental health services] for suicide watch and stuff like that… so for us there was that added stuff as well’.

Financial insecurity/socioeconomic status

‘I didn’t have a house and lived in that camper. Yeah, so it just didn’t work out, otherwise she would have gone’.

Domain 2: societal norms of weight and body size

Age

‘Like, a weight problem, like, at the time he was only 6 years or 7 years’.

‘… we were kind of shocked because they said that [SON] was, like, obese or something … I don’t think he’s overweight at all … Because he’s really tall … so I don’t understand, like, what sort of weight should he have been because he was, he’s just like a, he was like a normal kid. So I don’t understand what is overweight and underweight. Because I’ve seen some, not being mean, but overweight kids, and he wasn’t overweight’.

Gender

‘She might develop an eating disorder and I don’t want that. I’d rather, you know, it’s weird, but I’d rather she be overweight than underweight, you know what I mean? I’d hate to deal with an anorexic daughter because that’s hard work’.

Perceived genetic disposition

‘You know … it’s just the way it is sometimes. Some people get good genes, some people get other genes and it means it doesn’t work out’.

Domain 3: historical experiences of healthcare

Weight stigma and discrimination

‘… having visited for something else entirely different and then being told kind of ‘your child’s obese and we are going to refer you’ and just doing it front of him […] it was just even in the way that it was delivered and I was kind of not expecting it. I mean, I can see that he’s, he’s a bit chunky, but I just, I don’t know […] [the referral] was a bit off-putting’.

Racism

‘… people will judge you for what and where, what colour you are or whatever… [it] just made me more determined to get in there and do what I had to do’.

Mediator 1: respectful, compassionate care mitigated past experiences

‘It was not just the families, but also the, what do you call them, the workers … Very supportive, non-judgmental. I think that made a big difference and ‘yes we are going to go’ because they are not judging you … the staff was very supportive’.

Domain 1: obesity sits within the context of multiple other complex stressors for families in NZ

Participation in the Whānau Pakari service was affected by the multiple complex stressors of living in contemporary NZ. These were acute, one-off adverse events, such as a death in the family, and chronic, ongoing challenges, such as financial insecurity. Childhood obesity and overweight as a health concern sat within the context of multiple other important concerns for families. Participants were often living in ‘crisis mode’ or dealing with multiple challenges at once, including: financial and food insecurity, suicide, abusive relationships, deaths in the family, mental health issues, disability, relocation, marriage and family break-ups, fostering children, children being raised by other caregivers, drug use and significant other illnesses.

For parents of children with multiple health conditions, especially mental health concerns or autism spectrum disorder, addressing weight was often not perceived to be as important compared with other competing family health concerns. Parents and caregivers also reported the challenges of balancing multiple demands such as long work hours, shift work and extracurricular activities alongside attending Whānau Pakari.

I think he had one of his sporting things on and I was doing 50 hours a week at that time and I was like ‘oh, my God, I can’t do it’, I couldn’t do it. I mean, if he needed, if I felt like he needed to be there, I would get him there, like, it’s, my work’s not that important. Weeds and shit can wait, you know, like, people can wait um if it was a, if I felt like it was serious. I would have got him there, but I just yeah.

Similarly, socioeconomic deprivation and food insecurity was perceived to be a more immediate and pressing concern than childhood overweight or obesity. Both initial attendance and ongoing retention were affected by a lack of participant resources, even if participants expressed a desire to attend. Participants who engaged with Whānau Pakari and other services despite the impact of adverse stressors appeared to have more resources, and thus were less affected by this domain.

Domain 2: societal norms of weight and body size affect how people experience seeking care for weight

Societal norms and beliefs around weight and body size led to the minimisation of obesity and the fear of stigmatisation for participants (see also domain 3). These manifested differently according to the age, gender and the perceived role of genetics in obesity, and resulted in lower engagement. An exception was participant beliefs around perceived genetic propensity towards obesity, which in some cases led to higher rather than lower participant engagement.

The age of the child involved in the service affected the degree to which families chose to engage, due to a perception that children were too young to have weight problems, which was a key reason for both dropping out of the service early or declining input altogether. Children who were clinically overweight or had obesity were perceived to be a normal weight in early childhood and increasingly beyond. Some participants felt that while their child might not fit into a set of assessment criteria, this did not necessarily equate to their child being unhealthy.

When he got put in the […] ‘oh, he’s overweight’ box. And when you’re, like, ‘he’s not that overweight’, because it was just he wasn’t in their little boxes. I think that more annoyed me, is that they’ve got these sort of, like, ‘this is the normal weight for a 5 year old’. Well, there’s all sorts of different 5 year olds. He’s now 10 years and he is my height […] he’s a big guy.

There was a strong belief that if children were ‘big but active’, then their weight was not a concern.

… he’s always been big, but he’s really active. Like he wins the triathlons and the cross-country and he bikes and swims … it’s not like he can’t exercise or is held up, you know what I mean? And so we just thought well, and it’s not like he wasn’t healthy eating.

Families appeared more reluctant to engage their female children in services that are characterised as weight-related, both at initial recruitment and throughout the programme, for fear of their child developing self-esteem issues. Parents also reported their daughters were often reluctant to attend themselves.

To me it’s like you don’t need to involve her because she’s already self-conscious, soft-hearted, already upset about it sort of thing and, like, to me it was like more of a trigger. So, I was, like, no. I will do it my way. So I pulled back because it wasn’t worth it for her, you know what I mean? Like, her self-esteem and stuff is worth more than, you know, going to a dietitian where at home I can just stop giving her all that stuff to make her healthier. So that’s where it comes across wrong.

Overweight and obesity was often associated with perceived genetic propensity to obesity by participants. This was sometimes specifically linked to ethnicity, and specifically that Māori and Pacific Island peoples are ‘naturally big’. A perceived familial propensity towards overweight resulted in participants reportedly acting in two ways: either they did not want to engage because they felt that there was no point, given they perceived their weight to be genetic (panel 1), or they were compelled to engage more in order to counteract their genetics:

My side of the family is really obese so weight has always been an issue, so if you are trying to diet everyone gets behind you because they know what the challenge and the battle is. No, we don’t really care what other people say, we just get on with it.

Domain 3: historical experiences of healthcare affect future perception and engagement with services

Past experiences of healthcare influenced participants’ opinions, perceptions and behaviour in relation to seeking care again. This was a multidimensional phenomenon, acting across both weight and ethnicity. If participants had had negative experiences in the health system in relation to their weight or ethnicity, then they were less willing to engage with Whānau Pakari and other health services. This mostly affected participants who declined further input after their referral or who discontinued after one assessment. This was especially important if the referral experience to Whānau Pakari was negative, given that this may have been the first instance of being confronted about their child’s weight.

Basically they told her she was obese [at the B4 School Check] … Yeah, that she was obese for her age and they said this in front of her, and she was like ‘what is obese’? And they said, ‘you’re bigger than any other child your age’ but she’s not the only one […] So they say it in front of a child, it sort of knocks their self-esteem and their confidence right back.

While weight stigma was experienced across all groups of participants, there were few feelings of stigma about attending Whānau Pakari for those participants who engaged highly (≥70% of sessions):

There was nothing to be embarrassed about. You know, like secretive about it. It was something that I was doing for my kid, to help her get better in herself and if someone else had a problem then that was their problem, not mine. At the end of the day it is about her. Not about what anyone else thought.

Experiences of racism in the healthcare system and in wider society affected how participants reengaged with health services. This included a wide range of race-related experiences from interpersonal to institutionalised racism. Likewise, participants recounted a variety of responses to these experiences from renewal of engagement and wanting to ‘prove them wrong’, to disengagement with outside entities and organisations, to internalised racism.

… we have been through so much stigmatisation that nothing more than one thing matters […] because for us it’s about the betterment of our children and our whānau [family] as a unit.

Mediator 1: respectful, compassionate care mitigated past experiences

Conversely, positive and respectful care received in both the Whānau Pakari programme and in other areas of the health system mitigated the effect of the first three determinants, particularly against the impact of past negative experiences of healthcare. A positive referral experience generally set a positive tone for interacting with the Whānau Pakari service itself.

So we decided yes, this would be an awesome programme for our daughter, because we wanted her to just have some stability at the time because she was just starting high school, going into a phase where people were judging and things like that, you know, building her self-esteem […] It’s helped her with her confidence and just building a life that’s easy for her, you know. So, yeah, I thank [referrer] for that and for putting us onto that programme too because it was really awesome. We, as a whānau, we enjoyed it, and just being able to support her in that programme.

Participants who did engage with Whānau Pakari reported that the care received in the programme was ‘different’ from previous care received and that the programme deliverers were ‘like a family’. For these families, the respectful and compassionate care countered some of the negative effects of past experiences.

It was just the people, that’s all it was. It was just the approach of the people to be honest um and that made us comfortable, and I go by my children a lot because if they’re uncomfortable well then they’re not the right people to be around for us. And they were comfortable.

The social and team aspects of Whānau Pakari were beneficial for families, as well as the perceived extra care received.

I liked it. I didn’t think I was going to. I thought ‘oh, this is going to be stupid’, but no it wasn’t. It was actually a bit of an eye opener. I actually learnt something. And then we just recently got her blood tests and all that done again because through the doctors they didn’t do no diabetic tests or anything like that. Through Whānau [Pakari] they did. They did heaps more than the doctors did. So I think that’s pretty much why we stayed with them, it was like ‘aha, we can get some serious help here’.

Figure 1 summarises the interacting and mitigating domains affecting participant engagement.

Figure 1.

The three interacting factors that influence participant engagement in Whānau Pakari. Respectful, compassionate care can partially mitigate the effects of these determinants.

Discussion

This study found that engagement in Whānau Pakari was determined by the degree to which participants were affected by three interactive domains: complex adverse life stressors, societal norms of weight and body size, and past experiences of healthcare. These complex mechanisms operated at multiple levels including at the service, health system and wider societal levels, so that experiences at the seemingly distal societal level could still have an impact on participant engagement at the service level. While the impact of these factors was evident across all four groups, some participants appeared to be resilient to the impact of these determinants. Additionally, respectful and compassionate care appeared to act as a positive mediator. Conversely, participants who declined further input after their referral were more likely to be experiencing greater life stressors without the resources to overcome them. Participants also appeared to be affected by societal norms of weight with regards to age, gender and the perceived impact of genetics, and negative experiences of healthcare often resulted in complete disengagement.

We were surprised that clear recommendations for specific changes to internal programme aspects were not forthcoming from participants across all levels of attendance, as this was a specific intent of the project. Although factors such as the difficulty of attending programme sessions with shift work and other stressors were identified as a barrier by some participants, there was no clear consensus on factors such as timing and location. While forces external to the service affected engagement, our study indicates that there are opportunities at the service level to facilitate initial and continued engagement in Whānau Pakari, and potentially other services. Despite the negative experiences of participants in the health system (both weight and non-weight related), the care received in Whānau Pakari by deliverers was generally seen as ‘different’, and a key reason for wanting to continue with the service.

In our study, many participants who declined further engagement after their referral were reluctant to identify their young children as having weight issues and requiring assistance. Past research has identified multiple reasons for parental reluctance to identify overweight in their children,29 including not recognising obesity as a ‘disease’ and therefore not warranting the same attention as other health concerns, and wanting to avoid further stigmatising their child. Our data suggest that families are especially concerned with the mental health of their children, which was often perceived to be more important than identifying and addressing overweight and was a key reason for declining referrals. There appears to be a disconnect between the focus on early life intervention due to the expected growth trajectories of young children with overweight or obesity into obesity in adolescence and adulthood30 and the concerns and priorities of parents with young children.

Research indicates that parents of girls with overweight or obesity are more likely to enrol them in healthy lifestyles programmes than families with boys with overweight or obesity.10 The contrasting findings of our study, which also included participants who declined their referral, show clear parental concern for the mental health and self-esteem of their daughters, which may reflect a desire to focus on positive body image, self-esteem and mental health and avoid increasing body dissatisfaction.31 The findings of this study would suggest that the differences in how men and women experience weight in society contributes towards the differing retention rates between male and female participants at the service level. It is concerning that two important health issues—overweight and mental health—are pitted against each other as perceived incongruent concerns, given that both are significant causes of ill-health among children and adolescents, and suboptimal health-related quality of life was identified in a previous cohort with weight issues.2

Puhl and colleagues argue that message framing with regards to terminology is vital in childhood obesity programmes, in order to prevent further stigmatisation of families seeking help for weight.32 While the Whānau Pakari programme aims to be non-judgemental and non-stigmatising, it is equally important that the referral to the service is perceived to be non-stigmatising by families in order to encourage engagement. Given the impact of the referral experience to Whānau Pakari on initial and continued engagement with the service, the referral process must be respectful and compassionate, with an acknowledgement of past instances of stigma and discrimination. The sensitivity of weight as a discussion topic requires non-judgemental language, compassion and an acknowledgement of the wider context and potential pressures on the family.32

As in previous studies,33 many participants in this study had experienced weight stigma, blame and judgement from health professionals as well as a societal culture of weight bias. Indigenous participants often experienced this in addition to varying forms of racism. The impact of racial discrimination on healthcare use in NZ is well-documented,34 35 and the compounding impact of multiple stigmas is likely to contribute towards differential attendance rates between Māori and NZ Europeans. Previous weight bias and racism which occurs outside the service may play a role in participant reluctance to engage with Whānau Pakari. Further research should investigate the role of racism and weight stigma in engagement with healthcare for weight issues among marginalised ethnic groups.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the large sample size across participants with varying levels of engagement which allowed for in-depth and broad analysis. In addition, this study included data from a targeted group of participants (those who declined further contact after referral) whose lack of contact with the service limits the power of quantitative methods in drawing conclusions, and who are typically difficult to recruit, as recognised in previous studies.10 Finally, there was good representation from families with Māori children who comprised approximately half of the interviews, allowing us to draw conclusions for a group whose voice is historically absent from obesity research.

The main limitation of this study was the lack of child and adolescent voice with regards to their experiences with Whānau Pakari, as only five interviews included the child or adolescent as a participant. While it was intended to conduct interviews with families, many parents at recruitment were reluctant to involve their children due to the sensitivity of material discussed or were unable to involve them due to timing issues. This meant that children’s experiences have mainly been explored through their parents’ accounts, rather than through their own voice. In addition, previous literature has largely focused on the effect of child/adolescent gender rather than parent gender on perceived barriers to engagement.10 In our study, the majority of participants were mothers or female caregivers, which may have affected the results. While this study included a range of participants from a variety of different backgrounds (table 1), it lacks specific participant demographic information such as age, socioeconomic status and education level. Finally, it is possible that participants were discretionary in what they chose to share; however, the disclosure of extremely personal and sensitive experiences suggests that any researcher–participant power dynamics were overcome by steps the interviewers took to mitigate this difference (see online supplemental appendix 1 COREQ checklist).

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study found that much of the difference between Whānau Pakari participants who engaged highly and those who did not engage appeared to be due to the degree to which participants were affected by the impact of factors at the system and societal levels. Focusing purely on weight in multicomponent interventions does not acknowledge the complexity of contemporary family life. However, family-based multidisciplinary intervention programmes such as Whānau Pakari are an opportunity to acknowledge the wider societal challenges affecting achievement of healthy lifestyle change. Health professionals and providers can engage in respectful and compassionate care to help counteract past negative experiences of healthcare. Referral pathways for healthy lifestyle change programmes need to be as flexible as possible to remove any barriers to engagement, and referrers need to develop a deeper understanding of the importance of the referral conversation in relation to weight. Future research should focus on specific strategies to facilitate engagement at different points of contact with family-based multidisciplinary healthy lifestyle services. Respectful, compassionate care is critical to enhanced retention in programmes, and ongoing engagement in healthcare services overall.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr Donna Cormack (Te Kupenga Hauora Māori, University of Auckland) for her contribution to the research and critical appraisal of the manuscript. We also thank the participants of Whānau Pakari and their families.

Numerous authors within our research group are increasingly aware that the use of terms such as obesity are contested and increasingly problematic, partly due to the experiences of participants in terms of weight stigma. We have therefore used this term where it relates to referenced works, prevalence, and to communicate to the biomedical community, but have used alternate terms wherever possible to ensure a person-centred approach, prioritising the experience and voice of those working towards achieving healthy lifestyle change.

Footnotes

Correction notice: The article has been corrected since it was published, as Figure 1 has been updated with an image of a higher resolution.

Contributors: CEKW was involved in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation and writing of the manuscript. NTR contributed towards study design, data collection and manuscript appraisal. EJW contributed towards study design, oversaw analysis and interpretation and was involved in writing of the manuscript. PLH was involved in study design and critical appraisal of the manuscript. YCA was involved in study design, analysis, interpretation and writing of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was funded by A Better Start National Science Challenge and Cure Kids. The funders had no role in the conduct of the research, study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript and in the decision to submit the article for publication. The researchers are independent from the funders and all had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the Whānau Pakari Barriers and Facilitators study was granted by Central Health and Disability Ethics Committee (NZ) (17/CEN/158/AM01). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants, or informed assent with proxy parental consent in the case of the child and adolescent participants aged under 16 years.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Lakshman R, Elks CE, Ong KK. Childhood obesity. Circulation 2012;126:1770–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson YC, Wynter LE, Treves KF, et al. Assessment of health-related quality of life and psychological well-being of children and adolescents with obesity enrolled in a new Zealand community-based intervention programme: an observational study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015776 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson YC, Wynter LE, Butler MS, et al. Dietary intake and eating behaviours of obese New Zealand children and adolescents enrolled in a community-based intervention programme. PLoS One 2016;11:e0166996. 10.1371/journal.pone.0166996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson YC, Wynter LE, Grant CC, et al. Physical activity is low in obese New Zealand children and adolescents. Sci Rep 2017;7:41822. 10.1038/srep41822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson YC, Wynter LE, Treves KF, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in obese New Zealand children and adolescents at enrolment in a community-based obesity programme. J Paediatr Child Health 2016;52:1099–105. 10.1111/jpc.13315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Report of the Commission on ending childhood obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Connor EA, Evans CV, Burda BU, et al. Screening for obesity and intervention for weight management in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services Task force. JAMA 2017;317:2427–44. 10.1001/jama.2017.0332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skelton JA, Beech BM. Attrition in paediatric weight management: a review of the literature and new directions. Obes Rev 2011;12:e273–81. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00803.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011;378:804–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelleher E, Davoren MP, Harrington JM, et al. Barriers and facilitators to initial and continued attendance at community-based lifestyle programmes among families of overweight and obese children: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2017;18:183–94. 10.1111/obr.12478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perry RA, Daniels LA, Bell L, et al. Facilitators and Barriers to the Achievement of Healthy Lifestyle Goals: Qualitative Findings From Australian Parents Enrolled in the PEACH Child Weight Management Program. J Nutr Educ Behav 2017;49:43–52. 10.1016/j.jneb.2016.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson YC, Wynter LE, Moller KR, et al. The effect of a multi-disciplinary obesity intervention compared to usual practice in those ready to make lifestyle changes: design and rationale of Whanau Pakari. BMC Obes 2015;2:41. 10.1186/s40608-015-0068-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson YC, Wynter LE, Grant CC, et al. A novel home-based intervention for child and adolescent obesity: the results of the Whānau Pakari randomized controlled trial. Obesity 2017;25:1965–73. 10.1002/oby.21967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson Y, Wynter L, O'Sullivan N. Two-Year outcomes of Whānau Pakari, a multi-disciplinary assessment and intervention for children and adolescents with weight issues: a randomised clinical trial. Pediatric Obesity 2020;e12693 10.1111/ijpo.12693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson Y. Whānau Pakari: a multi-disciplinary intervention for children and adolescents with weight issues [PhD thesis]. University of Auckland, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wild CEK, O'Sullivan NA, Lee AC, et al. Survey of barriers and facilitators to engagement in a multidisciplinary healthy lifestyles program for children. J Nutr Educ Behav 2020;52:528–34. 10.1016/j.jneb.2019.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid P, Paine S-J, Curtis E, et al. Achieving health equity in Aotearoa: strengthening responsiveness to Māori in health research. N Z Med J 2017;130:96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valencia RR. The evolution of deficit thinking: educational thought and practice. Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtis E. Indigenous positioning in health research: the importance of Kaupapa Māori theory-informed practice. AlterNative 2016;12:396–410. 10.20507/AlterNative.2016.12.4.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glover M, Kira A, Johnston V, et al. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to participation in randomized controlled trials by Indigenous people from New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the United States. Glob Health Promot 2015;22:1757. 10.1177/1757975914528961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole TJ. A chart to link child centiles of body mass index, weight and height. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002;56:1194–9. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Health NZ HISO 10001:2017 ethnicity data protocols, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.MAXQDA 2018 [program]. Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 2019;11:589–97. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Airini DBC, Johnson E, Luatua O, et al. Success for all: improving Māori and Pasifika student success in degree-level studies. Auckland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtis ET, Wikaire E, Lualua-Aati T, et al. Tātou tātou/success for all: improving Māori student success. Wellington: Ako Aotearoa National Centre for Tertiary Teaching Excellence, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atkinson J, Salmond C, Crampton P. NZDep2013 index of deprivation. Wellington (NZ): Department of Public Health, University of Otago, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Towns N, D'Auria J. Parental perceptions of their child's overweight: an integrative review of the literature. J Pediatr Nurs 2009;24:115–30. 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geserick M, Vogel M, Gausche R, et al. Acceleration of BMI in early childhood and risk of sustained obesity. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1303–12. 10.1056/NEJMoa1803527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puhl R, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res 2001;9:788–805. 10.1038/oby.2001.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puhl RM, Latner JD. Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation's children. Psychol Bull 2007;133:557–80. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith KL, Straker LM, McManus A, et al. Barriers and enablers for participation in healthy lifestyle programs by adolescents who are overweight: a qualitative study of the opinions of adolescents, their parents and community stakeholders. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:53. 10.1186/1471-2431-14-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris RB, Cormack DM, Stanley J. Experience of racism and associations with unmet need and healthcare satisfaction: the 2011/12 adult New Zealand health survey. Aust N Z J Public Health 2019;43:75–80. 10.1111/1753-6405.12835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris R, Cormack D, Tobias M, et al. The pervasive effects of racism: experiences of racial discrimination in New Zealand over time and associations with multiple health domains. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:408–15. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-037152supp002.pdf (106.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-037152supp001.pdf (101.4KB, pdf)