Abstract

A 51-year-old man presented with dyspnoea and basithoracic pain. Chest X-ray revealed bilateral pleural effusion, which was managed by bilateral chest drain placement. The pleural fluid analysis showed elevated lipase. Subsequent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated a large fistula from the tail of the main pancreatic duct to the left pleural space. Definitive treatment was accomplished with ERCP guided large pancreatic stents placement.

Keywords: endoscopy, pancreas and biliary tract, pancreatitis

Background

Pleural effusion is common in acute pancreatitis and is due to a chemically induced inflammation of the diaphragm and pleura resulting in sympathetic effusion.1 The activity of the pancreatic enzyme in the fluid is usually low, and once the intra-abdominal inflammatory process decreases, the pleural effusion resolves spontaneously.2

Pancreaticopleural fistula is a rare entity which causes large and recurrent pleural effusion. The mechanism is typically by leakage of an incompletely formed or ruptured pseudocyst.3 4 It may also develop as a consequence enzymatic disruption of the main pancreatic duct, which then drains posteriorly into the pleural cavity.2 Similarly, anterior duct disruption can result in pancreatic ascites.

Previous studies reported an incidence of 3%–7% of internal pancreatic fistulas in patients with chronic pancreatitis, which include pancreatic ascites and pleural effusions.5 Although the incidence of pleural effusion is difficult to determinate due to its non-specific presentation, it has been described in 0.4%–4.5% of patients with both acute and chronic pancreatitis6 or after traumatic or surgical disruption of the pancreatic duct.7

We present a case of bilateral pleural effusion caused by a single left pancreaticopleural fistula, which was diagnosed by pleural effusion analysis and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and successfully treated with octreotide, and endoscopically placed stents.

Case presentation

A 51-year-old man presented with 3-day worsening dyspnoea accompanied by respiratory dependent left basithoracic chest pain. He also reported abdominal bloating. He had a prior history of alcohol abuse and acute pancreatitis. Clinical findings included: tachypnoea and oxygen saturation of 88% on room air. Physical examination revealed: tachycardia, bilateral basal hypoventilation on auscultation and dullness on percussion of the right lung.

Investigations

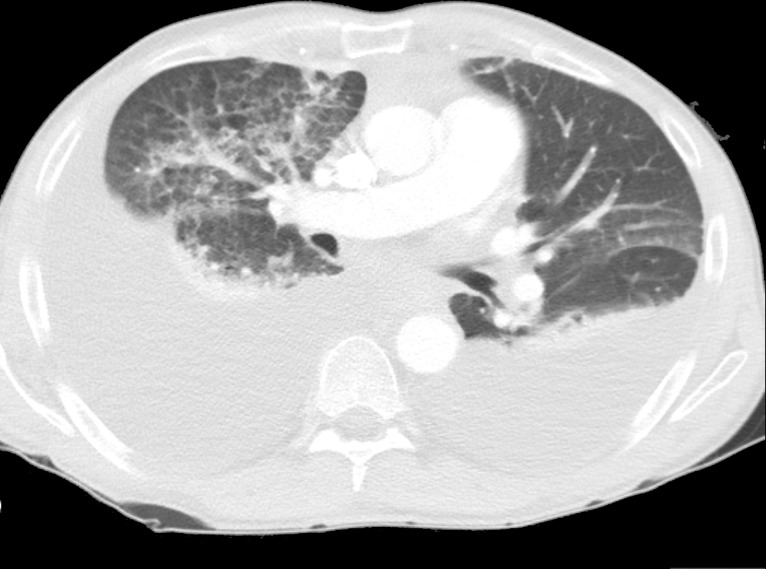

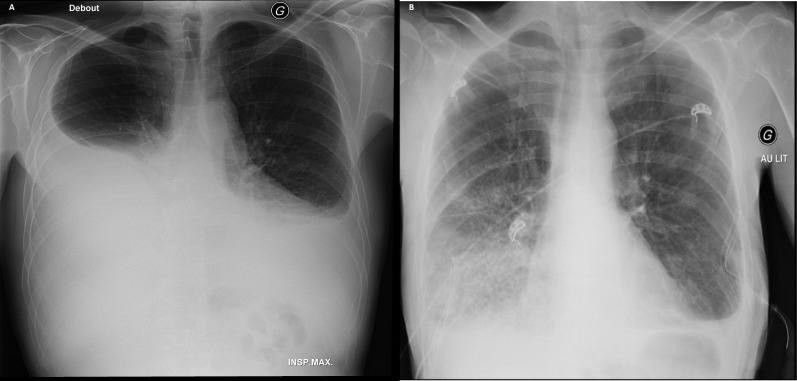

Chest X-ray showed an important bilateral, yet right side dominant pleural effusion. Laboratory studies were significant for an inflammatory syndrome with leucocytosis (15.1×109/L), elevated C reactive protein (132 mg/L) and elevated lipase (1456 U/L). Contrast enhanced CT scan revealed Balthazar C acute pancreatitis (figure 1) with voluminous bilateral pleural effusion (figure 2). The workup was completed with an abdominal ultrasound, which showed no dilatation of the common biliary duct and no cholelithiasis.

Figure 1.

Axial portal venous-phase CT scan showing enlargement of the pancreas (*) and infiltration of peripancreatic fat (arrows).

Figure 2.

CT scan showing bilateral pleural effusion (1.5 L on the right side and 0.9 L on the left side).

Pleural effusion was initially managed by placing bilateral chest drains (figure 3A, B). The right chest drain drained initially 4.1 L in 24 hours. It was left in place a total of 4 days and drained approximately 50 mL of fluid per day. The left chest drain drained 1.5 L in 24 hours, and then approximately 230 mL per day until it decreased to 40 mL per day, which allowed the drain removal after 14 days. Fluid analysis showed an exudative fluid with a high level of lipase (>100 000 U/L).

Figure 3.

(A) Initial chest X-ray, (B) chest X-ray after drainage.

Subsequent ERCP demonstrated a large fistula from the main pancreatic duct located in the tail of the pancreas to the left pleural space.

Treatment

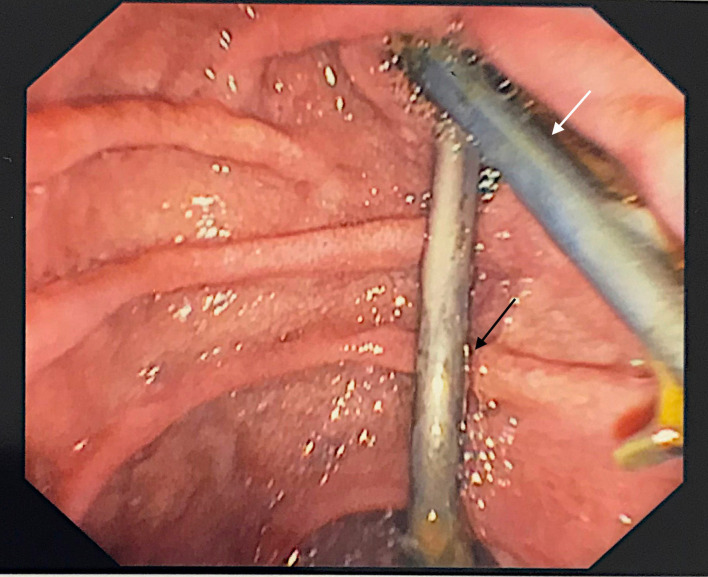

The patient was started on oxygen therapy, intravenous fluid resuscitation and subcutaneous octreotide at 0.1 mg three times per day. Our patient then underwent ERCP. Cannulation of the major papilla was performed, and contrast injection revealed a 7 mm common bile duct. Sphincterectomy was performed, followed by placement of a plastic 7 cm/10 French stent in the common bile duct (figure 4). Subsequent cannulation of the pancreatic duct and contrast injection showed a fistula communicating from the tail of the pancreas to the pleural space (figure 5A). A plastic 9 cm/7 French stent was placed in the pancreatic duct (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Endoscopic view of common bile duct stent (white arrow) and pancreatic stent (black arrow).

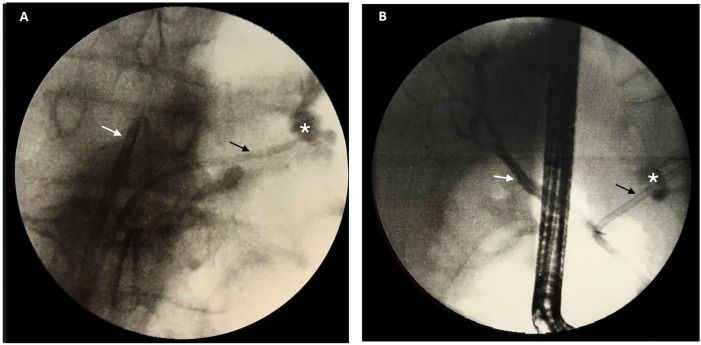

Figure 5.

(A) Cholangiopancreaticogram showing common bile duct stent (white arrow) and pancreatic duct stent (black arrow) with a pancreaticopleural effusion at the level of the pancreatic tail with contrast extravasation (*). (B) Cholangiopancreaticogram showing common bile duct stent (white arrow) and a longer pancreatic stent (black arrow) covering the entire fistula (*) at 7 days.

Due to the recurrence of bilateral pleural effusion, the patient underwent another ERCP 7 days later. The common bile duct plastic stent was in place and was easily removed. Distal migration of the plastic stent in the pancreatic duct was then visualised, and therefore subsequently removed, and replaced with a plastic stent larger in length and calibre (14 cm/8.5 French). Fluoroscopic examination showed that the larger stent covered the totality of the fistula and therefore allowed correct fistula bridging (figure 5B).

Outcome and follow-up

The patient improved and was discharged home after 3 weeks of hospitalisation. After 4 months, despite minimal residual pleural effusion, the patient remained asymptomatic. However, he subsequently developed chronic calcifying pancreatitis with an acute episode due to persistent alcohol consumption. The management of the calcifying pancreatitis required multiple ERCPs with various stent placements, unrelated to the original pancreaticopleural fistula, to alleviate recurring stenosis. These repeated ERCPs appeared to show an improving pancreaticopleural fistula. However, repeated ERCPs are not generally practiced for pancreaticopleural fistula follow-up, and therefore an appropriate magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was scheduled 10 months after the diagnosis. The subsequent examination showed complete resolution of the fistula.

Discussion

Typically, pancreaticopleural fistulas are seen in middle-aged men who present with respiratory symptoms such as dyspnoea or cough.8 9 Pancreaticopleural fistulas are predominantly associated with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis,10 11 but it has also been described in idiopathic pancreatitis and trauma.6 Abdominal pain has been reported in approximately only in a third of cases.12 Patient history usually reveals chronic alcohol consumption and possibly a prior history of acute pancreatitis.

Clinical signs associated with pleural effusion found on physical examination include decreased basal breath sound or dullness to percussion. Pleural effusion can be voluminous and has a high tendency to recur. Elevated serum lipase and amylase are usually found in laboratory testing, and blood count values are non-specific. Analysis of pleural fluid shows an exudative liquid with high levels of lipase. High levels of pancreatic enzymes are characteristic of pancreatic related pleural effusion, but can also be found in acute pancreatitis, pneumonia, oesophageal rupture and malignancy.13

Chest radiography reveals voluminous and usually left-sided pleural effusion. Right-sided14 or bilateral pleural effusion are rare.15 16 The predominance of left-sided pleural effusion is explained by the anatomical location of the pancreas and its proximity to the left pleura, oesophageal and aortic hiatus. In acute pancreatitis, the pancreatic fluid tends to drain into the posterior pararenal space and pelvic extraperitoneal space.17 Progression of acute pancreatitis can lead to an extension of the pancreatic collection to the mediastinal space forming mediastinal pseudocyst or pancreaticopleural fistula. A study exploring the peripancreatic fluid extension to the mediastinum with CT imaging showed anatomic pathways of peripancreatic fluid drainage. Most of the fluid drains through the oesophageal hiatus, aortic hiatus and inferior vena cava hiatus or extends via the left diaphragmatic hiatus.18

After chest radiography and thoracentesis, the next step is usually abdominal CT. The sensitivity of CT in demonstrating the fistulous tract is approximately 50%.8 However, it gives relevant information on pancreatic anatomy as well as the size and location of the pleural effusion. MRCP, with a sensitivity of 80%,19 has been shown to be the best non-invasive examination for both identifying pancreaticopleural fistula and guiding further management. The diagnosis can be confirmed with ERCP, which demonstrates the fistulous tract in 70% of cases.8

Evidence regarding the management of pancreaticopleural effusion are limited to case reports and small case series. Traditional management is medical, followed by surgical intervention. Therapy consists of repeated thoracocentesis or tube thoracostomy and anti-secretagogues drugs.2 Total parenteral nutrition and bowel rest were historically applied in order to avoid stimulation of exocrine pancreatic secretion. Recent studies showed that early feeding in patients with pancreatitis improved the course of the disease by reducing infectious complications, organ failure and mortality.20 Octreotide has been mostly studied in pancreatic surgery to prevent the formation of fistula and has been shown to significantly reduce the time to fistula closure.21 Due to its inhibitory action on both exocrine and endocrine functions of the pancreas, it has been used widely in treating pancreaticopleural fistulas. The initial dose of 50 µg is given subcutaneously three times per day and titrated up to 250 µg three times per day.6 The success rate of conservative treatment varies between 30% and 60%.9 10

The first successful endoscopic management of pancreaticopleural fistula with stent placement was reported by Saeed et al in 1993.22 Initially, preoperative diagnostic information about duct anatomy was obtained by endoscopic retrograde pancreatography. Stent length was chosen in order to cover the entire fistula and bridge the site of leakage, and stent placement was undertaken during the same procedure. Since then, many patients have been successfully treated with pancreatic duct stenting.8 9 22 23

Fistula closure is facilitated by a bridging pancreatic stent mainly because it reduces ductal pressure and acts as a mechanical seal. The role of sphincterectomy alone is unclear but has shown good outcomes in a few reported cases. One of the four cases of pancreaticopleural fistula presented by Dehrbi et al was managed with sphincterectomy alone because of stent placement failure due to difficult anatomy. The results were favourable, demonstrating a decrease in the size of the effusion on follow-up chest X-ray and CT.3 Similarly, another study showed good outcomes with sphincterectomy alone, but long term data on the evolution of these patients remains unknown.24

There are no guidelines on the optimum duration of drainage for pancreaticopleural fistulae. In the study of Saeed et al, stents were removed after 6 weeks which led to fistula resolution without recurrence after 14–30 months of follow-up.6 Conservative management periods with stent placement and octreotide continuation of 2.5–6 months have been employed.3

Finally, surgery may be required after the failure of medical and endoscopic management or recurrence of the fistula. It consists of distal pancreatectomy or pancreatojejunostomy in order to decompress pancreatic duct.7

Our patient presented with the very rare occurrence of a bilateral pleural effusion secondary to a single left pancreaticopleural fistula, which was treated with octreotide and plastic stents. Most cases of massive bilateral pleural effusion described in the literature originated from a pseudocyst, which extended through the mediastinum.25 In their review, Rocky and Cello identified that most patients (79%) with pancreaticopleural effusion were found to have a pseudocyst.6 In our case, the patient presented a fistulous tract between the pancreatic duct and left pleural space without pseudocyst. Other cases have demonstrated the occurrence of bilateral pleural effusion with fistulous tract associated with other potential causes such as trauma16 or subjacent pulmonary disease.15 Another case similar to ours with massive bilateral effusion was reported but was treated surgically due to technical difficulties in stent placement.26

The presentation of pancreaticopleural fistula is often misleading since patients present mainly with respiratory symptoms. Elevated levels of lipase in the pleural fluid is a clue to the diagnosis. Initially, medical treatment and endoscopy are recommended in the management of pancreaticopleural fistulas. Management of non-healing fistula is finally done by definitive surgical intervention. Our patient with a bilateral pleural effusion secondary to a single left pancreaticopleural fistula was successfully managed without surgery.

Learning points.

Bilateral pleural effusion can in rare cases be caused by pancreaticopleural fistula and should be suspected in a patient with recurrent pleural effusion not responding to thoracocentis and prior history of alcohol abuse and pancreatitis.

High level of pancreatic enzyme in the pleural effusion is an important clue to the diagnosis.

Pancreaticopleural fistula is managed medically with octreotide and endoscopically with stent placement

Surgery may be required after failure of medical and endoscopic management or recurrence.

Footnotes

Contributors: Supervised by HZ. Patient was under the care of HZ, IK (junior doctor), OS (junior doctor) and GH. Report was written by IK, OS and HZ.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Karkhanis VS, Joshi JM. Pleural effusion: diagnosis, treatment, and management. Open Access Emerg Med 2012;4:31–52. 10.2147/OAEM.S29942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgess NA, Moore HE, Williams JO, et al. A review of pancreatico-pleural fistula in pancreatitis and its management. HPB Surg 1992;5:79–86. 10.1155/1992/90415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhebri AR, Ferran N. Nonsurgical management of pancreaticopleural fistula. JOP 2005;6:152–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado NO. Pancreaticopleural fistula: revisited. Diagn Ther Endosc 2012;2012:1–5. 10.1155/2012/815476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chebli JMF, Gaburri PD, de Souza AFM, et al. Internal pancreatic fistulas: proposal of a management algorithm based on a case series analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004;38:795–800. 10.1097/01.mcg.0000139051.74801.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rockey DC, Cello JP. Pancreaticopleural fistula. Report of 7 patients and review of the literature. Medicine 1990;69:332–44. 10.1097/00005792-199011000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Setty B, Nanjegowda V, Gowda N, et al. Management of pancreatico-pleural fistula: 5 years of experience. Int Surg J 2015;2:221–3. 10.5455/2349-2902.isj20150519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kord Valeshabad A, Acostamadiedo J, Xiao L, et al. Pancreaticopleural fistula: a review of imaging diagnosis and early endoscopic intervention. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2018;2018:1–6. 10.1155/2018/7589451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh YS, Edmundowicz SA, Jonnalagadda SS, et al. Pancreaticopleural fistula: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci 2006;51:1–6. 10.1007/s10620-006-3073-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King JC, Reber HA, Shiraga S, et al. Pancreatic-pleural fistula is best managed by early operative intervention. Surgery 2010;147:154–9. 10.1016/j.surg.2009.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron JL. Chronic pancreatic ascites and pancreatic pleural effusions. Gastroenterology 1978;74:134–40. 10.1016/0016-5085(78)90371-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali T, Srinivasan N, Le V, et al. Pancreaticopleural fistula. Pancreas 2009;38:e26–31. 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181870ad5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Branca P, Rodriguez RM, Rogers JT, et al. Routine measurement of pleural fluid amylase is not indicated. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:228–32. 10.1001/archinte.161.2.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namazi MR, Mowla A. Massive right-sided hemorrhagic pleural effusion due to pancreatitis; a case report. BMC Pulm Med 2004;4:1. 10.1186/1471-2466-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gowrinath K, Jyothi P, Raghavendra C. Unusual cause of bilateral pleural effusion. J Clin Diagn Res 2015;9:OJ02–3. 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12548.6109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain SK, Basra BK, Nanda G, et al. Rare case of internal pancreatic fistula in a young adult presenting with massive bilateral pleural effusion. BMJ Case Rep 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa K, Nakao S, Nakamuro M, et al. The retroperitoneal interfascial planes: current overview and future perspectives. Acute Med Surg 2016;3:219–29. 10.1002/ams2.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu H, Zhang X, Christe A, et al. Anatomic pathways of peripancreatic fluid draining to mediastinum in recurrent acute pancreatitis: visible human project and CT study. PLoS One 2013;8:e62025. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Materne R, Vranckx P, Pauls C, et al. Pancreaticopleural fistula: diagnosis with magnetic resonance pancreatography. Chest 2000;117:912–4. 10.1378/chest.117.3.912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yi F, Ge L, Zhao J, et al. Meta-analysis: total parenteral nutrition versus total enteral nutrition in predicted severe acute pancreatitis. Intern Med 2012;51:523–30. 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montorsi M, Zago M, Mosca F, et al. Efficacy of octreotide in the prevention of pancreatic fistula after elective pancreatic resections: a prospective, controlled, randomized clinical trial. Surgery 1995;117:26–31. 10.1016/S0039-6060(05)80225-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saeed ZA, Ramirez FC, Hepps KS. Endoscopic stent placement for internal and external pancreatic fistulas. Gastroenterology 1993;105:1213–7. 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90970-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Safadi BY, Marks JM. Pancreatic-pleural fistula: the role of ERCP in diagnosis and treatment. Gastrointest Endosc 2000;51:213–5. 10.1016/S0016-5107(00)70422-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munirathinam M, Thangavelu P, Kini R. Pancreatico‑pleural fistula: case series. J Dig Endosc 2018;09:026–31. 10.4103/jde.JDE_23_17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujiwara T, Kamisawa T, Fujiwara J, et al. Pancreaticopleural fistula visualized by computed tomography scan combined with pancreatograph. J Pancreas 2006;7:230–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonoda S, Taniguchi M, Sato T, et al. Bilateral pleural fluid caused by a pancreaticopleural fistula requiring surgical treatment. Intern Med 2012;51:2655–61. 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]