Introduction

Healthcare innovations are continually being introduced, but the arrival of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused providers and payers to rapidly reassess delivery methods and push telehealth to the forefront of patient care. Despite uncertain times, the healthcare industry has responded with flexibility, collaboration, and quick action to the urgent need to provide care while keeping patients and providers safe. During the pandemic, hospitals have been uniquely challenged to care for patients with acute and chronic conditions, despite the limited access to practitioners imposed by social distancing and shelter-in-place measures.

Prior to the pandemic, institutions were slow to implement telehealth. The hesitancy was in part due to lack of reimbursement models, limited comfort with virtual services and technology, legal concerns such as state licensure laws, and socioeconomic barriers [5]. COVID-19 abruptly shifted the care model from in-person to telehealth visits. Patients at high risk for severe COVID-19, such as individuals with comorbidities and those over the age of 65 years, were suddenly confined to their homes with no access to traditional care options [1]. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and most commercial insurers responded by temporarily allowing reimbursements for telehealth [2], and many states temporarily eased licensure requirements or administered temporary licenses for telehealth to ensure continued access to care [8]. Since then, hospitals that adopted telehealth have reported a substantial increase in virtual visits [4, 10, 21].

Here, we describe how the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) physician and rehabilitation community addressed the challenge of providing continued orthopedic care to patients by rapidly expanding its nascent telehealth platform. We explore the value telehealth added to our patients’ care and the lessons we learned along the way.

Pre-COVID-19 Era

HSS is an orthopedic teaching institution that addresses a range of simple and complex orthopedic and rheumatological diagnoses. A leader in musculoskeletal health, the institution’s purpose is to help people get back to what they need and love to do better than any other place in the world. In 2019, HSS had 421,095 outpatient physician visits and 292,041 rehabilitation visits. Its previous experience with telehealth ensured the institution was well equipped to produce an efficient and rapid change in care delivery.

In 2018, HSS rehabilitation began exploring telehealth to improve access to care for patients in response to changes in the healthcare environment. Alternative payment models (APM) were introduced in the Affordable Care Act under the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model and the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative. Under these models, hospitals are responsible for a patient’s episode of care over a 90-day period [3], which incentivized hospitals to decrease unnecessary costs and over-utilization. HSS responded by creating unique initiatives to deliver high-quality coordinated care that spanned the entire episode. Building a hospital infrastructure that supported innovation was necessary as more providers and payers recognized this shift. With the emergence of a new technology, telehealth proved to be a viable option in providing value-based care and enhancing a patient’s experience.

HSS@Home, a telehealth platform, was one innovation in response to the change in payment models, introduced in June 2018 as an alternative to traditional home care services. HSS@Home provides virtual face-to-face visits with HSS physical therapists for coordinated care during the immediate post-acute stage (0 to 30 days) following total joint arthroplasty. Physical therapists provide education, monitor the progress of home exercises, and enhance communication between the patient and surgeon, with the goals of minimizing complications and reducing unnecessary re-admissions [7]. Yao and colleagues have shown that 60 to 70% of all re-admissions following a total hip or a total knee replacement occur within the first 2 weeks of surgery [22]. In order to manage patient concerns post-operatively, HSS@Home provided a mechanism to facilitate communication between patient or therapist and the medical team. Timely interventions and guidelines for monitoring calf swelling, pain, and redness, as well as assessing shortness of breath, made it possible to address and remediate concerns without costly emergency department visits.

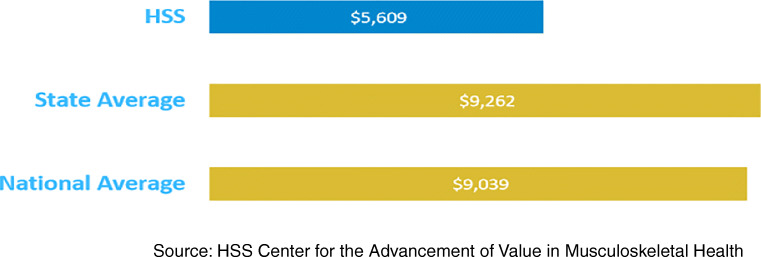

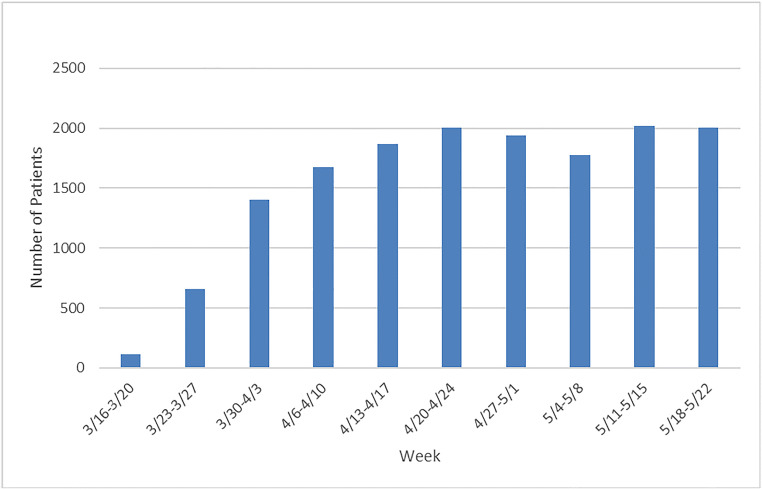

Patients and clinicians have reported high satisfaction with HSS@Home. Fisher and colleagues have demonstrated promising results in telehealth for the arthroplasty population. Out of 19 patients receiving HSS@Home, all 19 provided positive feedback [7]. HSS internal data, since inception, has shown HSS@Home patient rated their satisfaction as 4.91 out of 5 with 5 being high level of satisfaction. Prior to the pandemic, telehealth HSS@Home visits steadily increased (Fig. 1). HSS patients cost Medicare approximately 40% less in the post-acute phase of care compared to the New York State average (Fig. 2). Similar findings have shown telehealth can play a significant role in cost savings and effectiveness compared with in-person care for total knee arthroplasty [11, 12, 16, 17, 19]. Historically, CMS did not recognize physical therapists as telehealth providers, thereby limiting the ability to expand to other patients and service lines. However, the viability of HSS@Home has been demonstrated wherein all patient concerns were addressed and zero patients readmitted [7]. Although HSS@Home was limited to scale, the infrastructure built during this time laid the groundwork for future telehealth programming.

Fig. 1.

HSS@Home visits per month.

Fig. 2.

Average Medicare spending during 30 days after hospitalization, calendar year 2018.

COVID-19 and the Pivot to Telehealth

COVID-19 has caused unprecedented change in almost every industry, healthcare included. On March 20, 2020, New York State issued shelter-in-place orders and on March 25, 2020, canceled all elective surgeries. Non-essential care was temporarily halted, while providers focused on responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to respond to the change in standard care delivery, healthcare institutions across the country reported a large increase in telehealth visits. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) sought to decrease in person care and issued a temporary waiver for different clinicians to provide virtual visits [2]. In addition, multiple states relaxed licensure laws, allowing clinicians to treat patients regardless of state lines [8]. Telehealth has been implemented for both inpatients and outpatients at HSS.

In order to support New York City during the initial outbreak of the virus, HSS’s leadership reinvented the institution to provide necessary care to COVID-19 patients; HSS’s partnership with NewYork-Presbyterian (NYP) Hospital included the transfer of COVID-19 patients requiring hospitalization to HSS once NYP capacity was reached. Inpatient physical therapists, nurses, and physicians adopted the use of telehealth to communicate with patients admitted to the hospital presenting with milder symptoms. This initiative allowed the limited supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) to be used for nurses and doctors who were in direct contact with COVID-19 symptomatic patients. Inpatient physical therapists used telehealth to provide education on positioning and breathing and to prescribe exercises during the patient hospital stay. The education and exercises provided were designed to improve patients’ pulmonary functioning and musculoskeletal health and prevent unnecessary muscle tightness due to prolonged bed rest and deconditioning. Once discharged home, COVID-19 patients were scheduled for telehealth physical therapy visits to continue to improve musculoskeletal strength, activity tolerance, and ongoing monitoring throughout the recovery process.

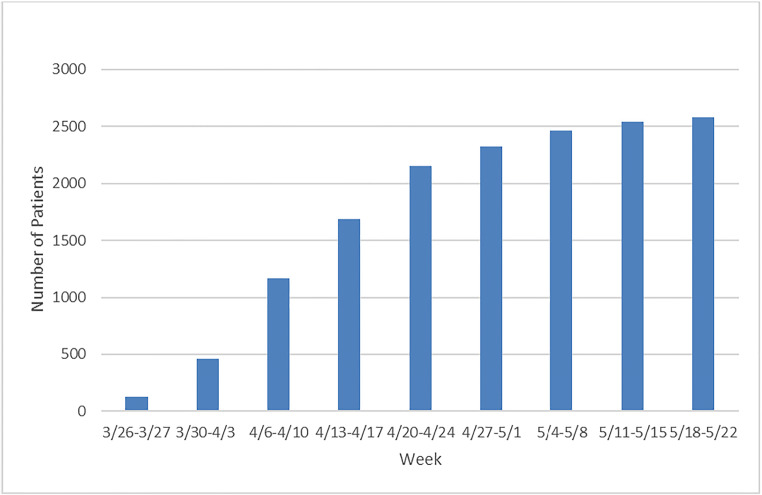

Recognizing the potential of telehealth to provide outpatient musculoskeletal care while complying with social distancing protocols, HSS implemented telehealth for existing and new outpatients throughout the institution. HSS physicians were able to use the infrastructure that the rehabilitation department designed for HSS@Home and scale it within the hospital, making HSS one of the first New York City hospitals to transition to outpatient virtual care. As of March 16, 2020, 210 HSS physicians were trained to use telehealth for virtual appointments. These physicians saw a steady increase and plateau in telehealth visits (Fig. 3), performing 15,461 telehealth visits between March 16, and May 29, 2020. This is due to a combination of rising office staff familiarity with the platform and expanding patient awareness.

Fig. 3.

Physician telehealth visits per week.

While the rapid adoption among practitioners was born out of necessity, the speed with which individual practices transitioned to care delivery method was quite impressive. Senior physicians in practice for more than three decades in conventional clinic models transitioned overnight to a computer-based synchronous video model for assessment and delivery of traditional care including indication for surgery or other interventional therapy. However, the most immediate benefit of telehealth was to assure continuity of care for patients who were in the vulnerable post-operative period following major surgical interventions.

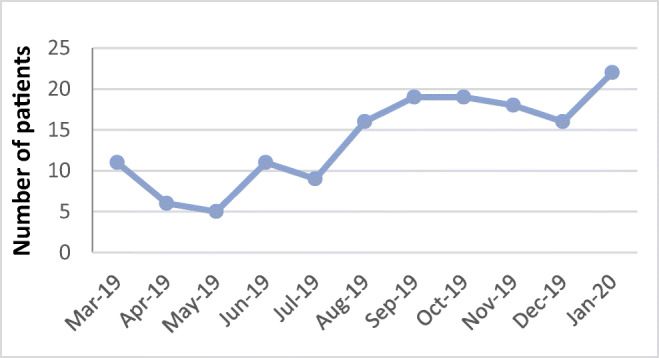

Simultaneously, HSS rehabilitation moved to provide continued care by organizing the 5058 patients who were receiving therapy services into three categories: patients who would benefit from a home exercise program and email follow-up, patients who had surgery less than 3 months prior and required in person care, and patients who would benefit from virtual care. On March 26, 2020, the first wave of therapists were trained and went live with outpatient telehealth. Over the following 2 weeks, four more waves followed, resulting in 173 therapists performing virtual treatment sessions. HSS rehabilitation has also seen a steady increase in telehealth visits, performing 15,492 telehealth visits between March 26, and May 22, 2020 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Rehabilitation telehealth visits per week.

As was the case in HSS@Home, outpatient physical therapy telehealth has shown signs of success. There is no statistical difference between patient satisfaction for in-person and telehealth evaluations and follow-up appointments, meaning patients are just as satisfied with telehealth as they are with in-person care. HSS rehabilitation created a tip sheet for colleagues clinicians to use which includes camera considerations, including tips on camera positions to achieve information in an efficient matter, and a red flag screening tool that is body part specific (Table 1).

Table 1.

Lower extremity tip sheet for clinicians to use including camera considerations and tips and a red flag screening tool that is body part specific

| Specific guidelines | Example | Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Camera considerations and tips | • Laptops and tablets | • Easier to tilt and place on flat surfaces |

| • Phones | • Easy to flip camera positions (vertical/horizontal) and hover over specific body parts | |

| • Surface heights | • Will influence camera angle, position of patient, and distance from camera | |

| • Lighting | • Place patient and camera in a bright area. Do not have light facing the camera | |

| • Positioning | • Have the patient move position to accommodate the camera as much as possible | |

| Red flag screening tool | • Recent increase in workload? | • Stress fracture |

| • Recent trauma? Inability to bear weight (Ottawa knee/ankle rules?) | • Fracture | |

| • Pain with rest? No change in pain with positional change? | • Neoplasm, fracture, cancer | |

| • Posterior knee tenderness/pain with local erythema/swelling? | • DVT | |

| • Pallor or feelings of coldness? | • Vascular insufficiency |

Source: HSS Rehabilitation Telehealth Evaluation Guidelines

Value Gained

Recent experiences with the implementation of telehealth at HSS have highlighted specific benefits and potential utility going forward.

Telehealth provides easy access to high-quality care regardless of geography, work, or personal constraints. Due to new relaxed licensure laws, HSS has reported an increase in patient care from outside the New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut region. In normal circumstances, there is a considerable burden for patients to present to traditional outpatient clinics. Many of the patients who come to our main campus in New York City do not live in the proximate area. This usually requires that the patient and/or an accompanying family member take considerable time from work, incur travel and parking expenses, and experience logistical stress in arriving at the proper office [4]. Telehealth can mitigate these costs and allow the patient to interact from the comfort of their own home or workplace. In the current crisis, patients also can practice safe social distancing and avoid potential high-risk situations such as using public transportation. Telehealth has enabled HSS clinicians to treat patients who are in need of musculoskeletal care but are unable to access clinics due to geographic, personal, or financial barriers. HSS has expanded its geographic outreach since CMS implemented policy changes in response to the pandemic [13].

Telehealth can provide continuity of care with the same care team from pre-operative, to the hospital stay, to full recovery. Home safety and discharge planning is critical prior to orthopedic surgery. Pre-operative physical therapy can recommend appropriate safety precautions within the patient’s home and order necessary post-surgical equipment to minimize the risk of injury after surgery. Once admitted to the hospital, surgeons can perform remote rounding on patients to answer questions, improve patient-physician engagement, and save physicians time by not having to travel throughout the hospital to visit each patient. Post-operatively, HSS@Home has already improved access to care (patients are seen within 24 h of discharge), decreased unnecessary re-admissions, and improved patient satisfaction in total hip and total knee replacements [7]. Patients can also use telehealth as an adjunct with traditional in person therapy, decreasing the overcrowding of clinics.

Telehealth can complement in-person care by having the physician or therapist assess a patient’s ability to function within a home setting. Seeing a patient within his or her home environment provides information that the patient may not think to mention in a traditional clinic visit. It can provide information such as amount of space in a patient’s home, the patient’s access to equipment, exposure to hazards, and ultimately his or her ability to perform exercises within the home or another off-site environment. Also, early anecdotal experience indicates that the patients, in their more familiar environment, are more receptive to information being delivered and have better recall of questions on their mind.

Finally, there is also a substantial benefit and opportunity for the provider. The physician or therapist can provide medical care from their own home during certain portions of the workweek, thereby reducing time lost to travel, avoiding the inefficiencies of clinic bottlenecks, and lessening personal burdens such as arranging childcare. In addition, telehealth enables both physician and patient to arrange consultations during off-hours such as evening and weekends, times that may be far more convenient for working patients but not conducive to traditional clinic hours.

Lessons Learned

As happens in many crises, the lessons learned from COVID-19 may outlast the emergency. It is clear to our institution that physicians’ and therapists’ use of telehealth will be one such remnant. As HSS continues to advance its telehealth platform, the implementation of lessons learned and strategies to elevate provider and user experience can facilitate use of telehealth as a mechanism for patient access to high-quality care. Telehealth infrastructure, through HSS@Home, allowed institutional expansion once New York City issued shelter-in-place orders. Clinician and administrative workflows were already being used in the rehabilitation department for telehealth and were easily transmittable throughout the institution.

Internet connectivity is widely accessible for patients and providers, but technological issues are inevitable. A support staff is necessary to troubleshoot technological downtime and configure patient access and connectivity. Establishing a permanent 24/7 support call center will help resolve technology and connectivity issues.

Telehealth can be used not only as a way to deliver care but also as a triage mechanism. The initial visit should remain on assessing and determining best course of treatment, whether that is referral to another provider, treatment through telehealth, or treatment through in-person visits. For many patients, the alternative is no access or limited access to orthopedic specialists. The effectiveness of care should be defined by patient outcomes—not whether the visit was conducted in person [9]. HSS internal data has shown when patients were asked “How would you rate your confidence that your rehab needs are being met through Telehealth?”, they responded with an average of 4.7 out of 5, with 5 indicating high level of satisfaction [6].

As with any novel medical technology, there is a clear learning curve associated with telehealth. In addition to the comfort of both the clinician and the patient, the main clinical hurdle we encountered was developing a proxy for the in-person hands-on physical examination. A conventional clinic consultation relies overwhelmingly on visual and verbal interaction between patient and clinician. Our practitioners universally agreed that this component of the interaction was replicated in the telehealth platform. In fact, certain subcomponents of the interaction such as reviewing and explaining details of imaging studies seemed to be superior with telehealth since the practitioner could “screen-share” with the patient and highlight relevant findings. However, the lack of hands-on examination required creative alternatives. At HSS, individual specialties and subspecialties developed virtual examination protocols and shared best practices among colleagues. Ultimately, the solutions involved having patients proceed through sets of physical activities (such as squatting, heel walking, toe walking for lower extremity motor testing) and manipulating readily available props in the home (such as lifting and maneuvering a full water bottle to test upper extremity neurologic function). Studies have shown that clinicians are able to successfully use several elements of a standard musculoskeletal assessment to evaluate patients with mild low back pain [20], non-articular lower limb pain [15], and knee pain [14] in countries where telehealth is widely available. Tanaka and colleagues have described a systematic virtual examination that can aid in triaging and managing common musculoskeletal conditions [18]. Patients can also assist in the exam by self-assessing certain musculoskeletal injuries using the Ottawa ankle and knee rules to determine need for additional care [9]. These best practice protocols are still evolving.

In conclusion, market pressure in the healthcare industry has resulted in a changing landscape to produce better outcomes at lower costs. The emergence of COVID-19 has fast tracked healthcare innovation to ensure safety and access to care. While flexibility during the COVID-19 era is necessary, we must also prepare for the long-term future. As the healthcare industry returns to a “new normal,” CMS and third-party payer support of telehealth will be invaluable to creating a better system for patients, providers, payers, and hospital systems. Continuing to reimburse for telehealth services stands to improve access to care and reduce overall costs.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Erica Fritz Eannucci, PT, DPT, OCS; Charles Fisher, MPT, MBA; Gwen Weinstock-Zlotnick, PhD, OTR/L, CHT; Cara Lewis, PT, PhD; and Matthew Titmuss, PT, DPT.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

M. Jake Grundstein, PT, DPT, MBA; Harvinder S. Sandhu, MD, MBA; and JeMe Cioppa-Mosca, PT, MBA declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human/Animal Rights

N/A

Informed Consent

N/A

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People who are at higher risk for severe illness. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html. Published May 14, 2020. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Fact sheet: Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. Available from https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- 3.Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available from https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/cjr. Accessed 29 April 2020.

- 4.Contreras CM, Metzger GA, Beane JD, Dedhia PH, Ejaz A, Pawlik TM. Telemedicine: patient-provider clinical engagement during the COVID-19pPandemic and beyond. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(7):1692–1697. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04623-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1601705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eannucci E, et al. Patient satisfaction for telehealth physical therapy services were comparable to in-person services during the COVID-19 pandemic [in press]. 2020. HSS J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Fisher C, Biehl E, Titmuss MP, Schwartz R, Gantha CS. HSS@Home, physical therapist-led telehealth care navigation for arthroplasty patients: a retrospective case series. HSS J. 2019;15(3):226–233. doi: 10.1007/s11420-019-09714-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HHS Office of the Secretary, Office for Civil Rights. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth. Available from https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Published March 30, 2020. Accessed May 10, 2020.

- 9.Hollander JE, Sites FD. The transition from reimagining to recreating health care is now. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. 2020;1(2). Available from https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0093.

- 10.Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: Evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(7):1132–1135. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moffet H, Tousignant M, Nadeau S, et al. In-home telehealth compared with face-to-face rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(14):1129–1141. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piccinin MA, Sayeed Z, Kozlowski R, Bobba V, Knesek D, Rush T. Bundle payment for musculoskeletal care: current evidence (part 1) Orthop Clin North Am. 2018;49(2):135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Policy changes during the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency. Telehealth.HHS.gov. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration. Available from https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/policy-changes-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency/. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- 14.Richardson BR, Truter P, Blumke R, Russell TG. Physiotherapy assessment and diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders of the knee via telerehabilitation. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(1):88–95. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15627237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell T, Piers T, Blumke R, Richardson B. The diagnostic accuracy of telehealth for nonarticular lower-limb musculoskeletal disorders. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(5):585–595. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell TG, Buttrum P, Wootton R, Jull GA. Internet-based outpatient telerehabilitation for patients follow total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(2):113–120. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shukla H, Nair SR, Thakker D. Role of telerehabilitation in patients following total knee arthroplasty: Evidence from a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(2):339–346. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16628996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka MJ, Oh LS, Martin SD, Berkson EM. Telemedicine in the era of COVID-19. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020. 10.2106/jbjs.20.00609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Tousignant M, Moffet H, Nadeau S, et al. Cost analysis of in-home telehealth for post-knee arthroplasty. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(3):e83. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truter P, Russell T, Fary R. The validity of physical therapy assessment of low back pain via telehealth in a clinical setting. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(2):161–167. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wosik J, Fudim M, Cameron B, et al. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Yao DH, Keswani A, Shah CK, Sher A, Koenig KM, Moucha CS. Home discharge after primary elective total joint arthroplasty: postdischarge complication timing and risk factor analysis. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(2):375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)