Abstract

Background:

The etiopathogenesis of congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO) has been inconclusive in spite of the numerous studies carried out to find the possible causative factor. The results of different studies have been conflicting and contradictory. It has been postulated that the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) are the pacemaker cells located in the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) and regulate the peristalsis in this region. Paucity of these cells may be one of the causative factors for congenital UPJO although there is no clear consensus on this issue. Therefore, the present study has been carried out to ascertain the role of ICC as one of the possible etiological factors for congenital UPJO. The aim of this study is to first identify the presence of ICC at UPJ, second to compare the average number of ICC in congenital UPJO with a control population without UPJO, and third to ascertain whether any correlation exists between the number of ICC and postoperative improvement in function of the affected kidney.

Materials and Methods:

A total number of 30 patients who underwent dismembered Anderson-Hynes pyeloplasty for congenital UPJO between June 2016 and November 2017, were compared with seven controls who underwent nephroureterectomy for various other reasons. The specimen was subjected to immunohistochemistry (IHC), and a quantitative comparison was made for the ICC between cases and controls. The preoperative and postoperative function was evaluated by renal diuretic scintigraphy.

Results:

The disease was more common among males in the ratio of 6.5:1, and there was a predominance of the left-sided involvement. In the studied cases, the average number of ICC seen for every high-power field (hpf) was 4.86 ± 0.76/hpf, whereas in control it was 11.74 ± 0.86/hpf (P = 0.04). The postoperative outcome, as measured by the improvement in split renal function, did not have any correlation with the number of ICC.

Conclusion:

The ICC are present at the UPJ and can be detected by immunohistochemistry due to their CD117 positivity. These cells are significantly low at this site in cases of congenital UPJO when compared to controls without any obstruction. The number of ICC bears no correlation to the postoperative improvement in function.

KEYWORDS: CD117, Congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction, immunohistochemistry, interstitial cells of Cajal, pyeloplasty

INTRODUCTION

Congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO) is a leading cause of obstructive uropathy in the newborn. It has an incidence of 1:1500 live births.[1,2] Numerous factors have been implicated for congenital UPJO; however, it is predominantly because of an aperistaltic segment. The underlying factors for the aperistaltic segment still remain a matter for debate.[3] Some studies suggest the role of neuronal factors or decrease in the number of pacemaker cells or combined theory involving both nerves and muscles, as a possible etiology.[4,5,6]

Subsequent to urine production by the kidney, its propulsion to the bladder is carried out by peristalsis of the ureter. This peristalsis is brought by pacemaker cells, the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) by generating slow-wave potentials. These cells, discovered by Santiago Ramony Cajal in 1893, have features similar to those identified in the gastrointestinal tract, as they express the tyrosine kinase receptor c-kit. When labelled with antibodies to proto-oncogene c-kit, they can be detected through immunohistochemistry.[6,7] In the gastrointestinal tract, the loss of this pacemaker activity of these cells has been established in the etiopathogenesis of Hirschsprung's disease and intestinal pseudo-obstruction.[8,9,10] It has been postulated that the loss of initiation, propagation, and coordination of the upper urinary tract peristalsis due to paucity of ICC may have a role in congenital UPJO.[11,12] The intent of the present work is to understand the association of ICC with congenital UPJO by studying the average number of ICC/high-power field (hpf) in the cases of congenital UPJO and comparing this with a control group. This study will also assess the impact of the number of ICC on the postoperative outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion criteria and study period

This is a prospective observational study. All the cases of congenital UPJO undergoing dismembered pyeloplasty at this center were included in the study. A total of 30 patients, who underwent Anderson-Hynes dismembered pyeloplasty as a treatment for congenital UPJO, were compared to control cases as defined below. The period of the study was from June 2016 to November 2017 when all the cases as well as controls were operated by the same surgical team. All patients and controls were provided with patient information sheet, and consent for participation in the study was taken on the patient informed consent form.

Cases with secondary PUJO, extrinsic causes of obstruction, solitary kidney, and redo surgery were excluded from the study.

Control cases

Seven cases of the pediatric population who underwent nephroureterectomy for other reasons like reflux nephropathy with nonfunctional kidney and Wilms' tumor during the same study period.

Histopathological examination

In all the cases, undergoing Anderson-Hynes pyeloplasty a segment of ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) was sent for histopathological examination (HPE). After making sections from the UPJ, it was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, followed by immunohistochemistry with the primary antibody against CD117. Xylene was used for deparaffinization and graded alcohol for the rehydration of the tissue section. The unmasking of antigen was carried out using heat-induced epitope retrieval system. This was followed by the application of 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min and then washed with buffered saline for 3 min. Subsequently, it was treated with anti-CD117 (PathnSitu-Ep10 clone) and counterstaining with hematoxylin. In the control group, a similar procedure was carried out for staining the UPJ segment.

Following the staining process, each specimen was reviewed for the presence of CD117-positive cells by a single pathologist. Each case and control was examined in hpf. The total number of ICC was counted in 10 hpf, and then, an average was taken in each case to determine the number of CD117-positive cells in each hpf. The CD117-positive cells were differentiated from mast cells by comparing the morphological characteristics of both the cells.

Postoperative evaluation and statistical analysis

All the patients undergoing pyeloplasty were evaluated at 6 months postoperatively when an ultrasound of the kidney, ureter, and bladder region and diuretic renogram was carried out. Success after surgery was defined as postoperative improvement in drainage pattern and improvement in the split renal function.

The statistical tool used was Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) Version 20 and Microsoft Excel. The Mann–Whitney U-test and Pearson correlation test were used for comparison between the two groups.

RESULTS

Demographic features

In this study, a total number of 30 cases were compared to 7 controls. The demographic features of both groups are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic comparison of the cases and controls

| Cases (n=30) | Controls (n=7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (months), median (range) | 8.5 (2-96) | 24 (8-60) |

| Sex (male:female) | 6.5:1 | 6:1 |

| Side affected (left:right) | 19:11 | 2:5 |

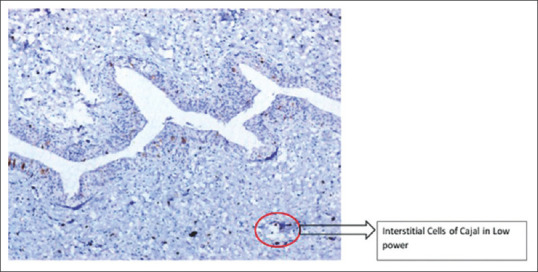

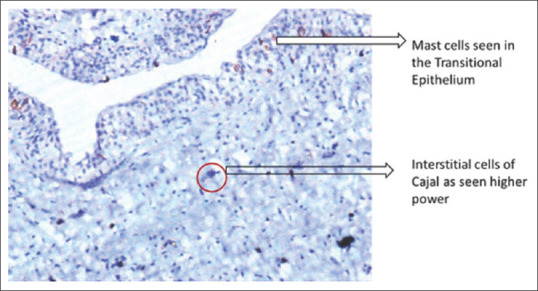

Identification of interstitial cells of Cajal

The ICC were identified by a thin cytoplasm, a large oval nucleus, and two dendritic processes as shown in Figure 1. These cells have to be differentiated from the mast cells based on the morphology of the cells and their location. The same has been shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Interstitial cells of Cajal seen in ×100 in case of ureteropelvic junction obstruction

Figure 2.

Interstitial cells of Cajal seen in ×200 in ureteropelvic junction obstruction

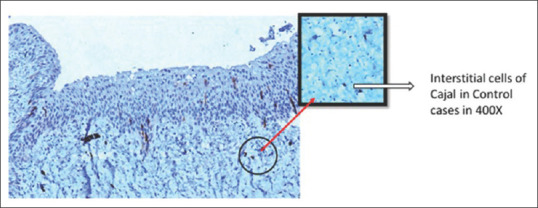

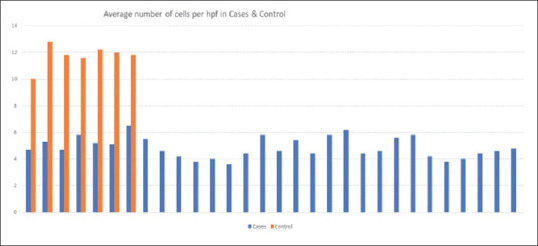

The average number of ICCs among the cases was 4.86 ± 0.76/hpf and that in control was 11.74 ± 0.86/hpf. The number of ICC/hpf was higher in controls as compared to cases. This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.04). Figure 3 shows ICC in higher magnification in controls. Figure 4 compares the average number of ICC/hpf in cases and controls.

Figure 3.

Interstitial cells of Cajal as seen in controls in ×400

Figure 4.

Average number of interstitial cells of Cajal in cases and controls

Influence of interstitial cells of Cajal on the postoperative outcome

The preoperative split renal function was compared with postoperative split function. Of the 30 cases that underwent pyeloplasty, 27 cases showed improvement in split renal function, and three cases had a fall in split renal function following the surgery. All the cases showed improvement in their drainage pattern following surgery.

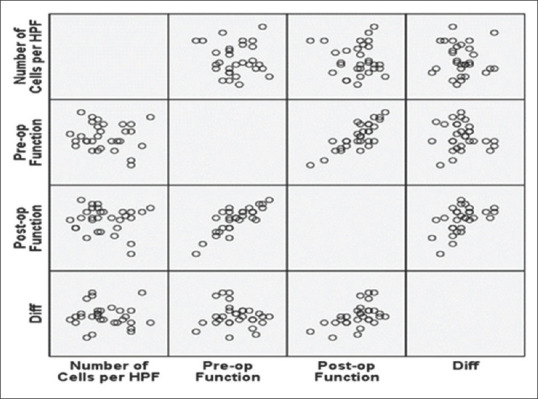

The effect of average number ICC on the postoperative improvement in split renal function was studied. This revealed no correlation between the number of ICC and postoperative improvement in split renal function. The Bland–Altman plot [Figure 5] shows no correlation between the postoperative change in renal function and the number of ICC/hpf.

Figure 5.

Bland–Altman figure showing no correlation between interstitial cells of Cajal distribution and improvement in postoperative split renal function

DISCUSSION

The predilection for male sex and left-sided involvement noticed in our study matches with previous studies on congenital UPJO.[13]

In our study, there was a statistically significant difference in the number of ICC observed between cases and controls; these results are also consistent with the other studies that compared ICC in UPJO and non-UPJO cases.[2,7,14,15]

We did not find any correlation between the number of ICC/hpf at UPJ and the postoperative improvement in split renal function. This finding is in contradiction to the findings by Inugala et al.[15] This could be attributed to the fact that following dismembered pyeloplasty, the postoperative drainage is gravity dependent and not by peristalsis; hence, the improvement in function is not subject to the initial number of ICC but depends more on surgical accuracy.

The pacemaker potential of ICC was recognized more than two decades back.[16,17] Their role has been established more than a decade ago in number of diseases such as intestinal pseudo-obstruction,[18] hypertrophic pyloric stenosis,[19] and achalasia[20] in the pediatric population.

Their role in the urinary system was identified by various animal studies.[21] They have pacemaker activity and under the influence of acetylcholine they generate and maintain peristalsis of the ureter.[22] They have an external ligand-binding component and an intracytoplasmic tyrosine kinase component. Thus, these cells mediate transmission of signals resulting in smooth muscle contraction.[23] In the entire urinary system, ICC are maximally distributed at the UPJ.[24]

It was postulated that the congenital UPJO could possibly be due to reduced number of these pacemaker cells.[7] This probably leads to the lack of regular and co-ordinated electrical slow waves, resulting in decreased contractile activity and subsequent loss of peristaltic activity.

However, the decrease in the number of ICC alone does not explain the entire pathophysiology of this complex disease. The multifactorial etiology of congenital UPJO was supported by studies showing atrophy and fibrosis of the smooth muscles with nonspecific inflammation at UPJ and increased deposition of Type 4 collagen and fibronectin.[24] Recent study by How et al.[3] concluded that there exists a variability of expression of neuronal markers including CD117. Hence, it is difficult to incriminate or exclude any single factor in the pathogenesis of this disease, and larger multicentric studies will be required to come to any definitive conclusion. Our study is limited by the number of subjects and single-center experience. Nonetheless, we conclude from our study that ICC are present at the UPJ and can be detected by immunohistochemistry due to their CD117 positivity. These cells are significantly low at this site in cases of congenital UPJO when compared to controls without any obstruction. The number of ICC bears no correlation to the postoperative improvement in split renal function.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberti C. Congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction: Physiopathology, decoupling of tout court pelvic dilatation-obstruction semantic connection, biomarkers to predict renal damage evolution. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:213–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senol C, Onaran M, Gurocak S, Gonul II, Tan MO. Changes in Cajal cell density in ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2016;12:89.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.How GY, Chang KT, Jacobsen AS, Yap TL, Ong CC, Low Y, et al. Neuronal defects an etiological factor in congenital pelviureteric junction obstruction. J Pediatr Urol. 2018;14:51.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Puri P, Hassan J, Miyakita H, Reen DJ. Abnormal innervation and altered nerve growth factor messenger ribonucleic acid expression in ureteropelvic junction obstruction. J Urol. 1995;154:679–83. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199508000-00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kajbafzadeh AM, Payabvash S, Salmasi AH, Monajemzadeh M, Tavangar SM. Smooth muscle cell apoptosis and defective neural development in congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction. J Urol. 2006;176:718–23. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eken A, Erdogan S, Kuyucu Y, Seydaoglu G, Polat S, Satar N. Immunohistochemical and electron microscopic examination of Cajal cells in ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E311–6. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solari V, Piotrowska AP, Puri P. Altered expression of interstitial cells of Cajal in congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction. J Urol. 2003;170:2420–2. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000097401.03293.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanderwinden JM, Rumessen JJ, Liu H, Descamps D, De Laet MH, Vanderhaeghen JJ. Interstitial cells of Cajal in human colon and in Hirschsprung's disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:901–10. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rolle U, Piotrowska AP, Nemeth L, Puri P. Altered distribution of interstitial cells of Cajal in hirschsprung disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:928–33. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-0928-ADOICO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns AJ. Disorders of interstitial cells of Cajal. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45(Suppl 2):S103–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31812e65e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apoznanski W, Koleda P, Wozniak Z, Rusiecki L, Szydelko T, Kalka D, et al. The distribution of interstitial cells of Cajal in congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45:607–12. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0454-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koleda P, Apoznanski W, Wozniak Z, Rusiecki L, Szydelko T, Pilecki W, et al. Changes in interstitial cell of Cajal-like cells density in congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44:7–12. doi: 10.1007/s11255-011-9970-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senguttuvan P, Jigy J. Profile and outcome of pelviureteric junction obstruction. Open Urol Nephrol J. 2014;24:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang X, Zhang Y, Hu J. The expression of Cajal cells at the obstruction site of congenital pelviureteric junction obstruction and quantitative image analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:2339–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inugala A, Reddy RK, Rao BN, Reddy SP, Othuluru R, Kanniyan L, et al. Immunohistochemistry in ureteropelvic junction obstruction and its correlation to postoperative outcome. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2017;22:129–33. doi: 10.4103/jiaps.JIAPS_254_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rumessen JJ, Thuneberg L. Pacemaker cells in the gastrointestinal tract: Interstitial cells of Cajal. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;216:82–94. doi: 10.3109/00365529609094564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomsen L, Robinson TL, Lee JC, Farraway LA, Hughes MJ, Andrews DW, et al. Interstitial cells of Cajal generate a rhythmic pacemaker current. Nat Med. 1998;4:848–51. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonucci A, Fronzoni L, Cogliandro L, Cogliandro RF, Caputo C, De Giorgio R, et al. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2953–61. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanderwinden JM, Liu H, De Laet MH, Vanderhaeghen JJ. Study of the interstitial cells of Cajal in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:279–88. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolle U, Piaseczna-Piotrowska A, Puri P. Interstitial cells of Cajal in the normal gut and in intestinal motility disorders of childhood. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:1139–52. doi: 10.1007/s00383-007-2022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCloskey KD, Gurney AM. Kit positive cells in the guinea pig bladder. J Urol. 2002;168:832–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pezzone MA, Watkins SC, Alber SM, King WE, de Groat WC, Chancellor MB, et al. Identification of c-kit-positive cells in the mouse ureter: The interstitial cells of Cajal of the urinary tract. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F925–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00138.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehrazma M, Tanzifi P, Rakhshani N. Changes in structure, interstitial Cajal-like cells and apoptosis of smooth muscle cells in congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Iran J Pediatr. 2014;24:105–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metzger R, Neugebauer A, Rolle U, Böhlig L, Till H. C-Kit receptor (CD117) in the porcine urinary tract. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:67–76. doi: 10.1007/s00383-007-2043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]