Abstract

Background:

Screening high-risk women for breast cancer with MRI is cost-effective, with increasing cost-effectiveness paralleling increasing risk. However, for average-risk women cost is considered a major limitation to mass screening with MRI.

Purpose:

To perform a cost–benefit analysis of a simulated breast cancer screening program for average-risk women comparing MRI with mammography.

Study Type:

Population simulation study.

Population/Subjects:

Five million (M) hypothetical women undergoing breast cancer screening.

Field Strength/Sequence:

Simulation based primarily on Kuhl et al8 study utilizing 1.5T MRI with an axial bilateral 2D multisection gradient-echo dynamic series (repetition time / echo time 250/4.6 msec; flip angle, 90°) with a full 512 × 512 acquisition matrix and a sensitivity encoding factor of two, performed prior to and four times after bolus injection of 0.1 mmol of gadobutrol per kg of body weight (Gadovist; Bayer, Germany). An axial T2-weighted fast spin-echo sequence with identical anatomic parameters was also included.

Assessment:

A Monte Carlo simulation utilizing Medicare reimbursement rates to calculate input variable costs was developed to compare 5M women undergoing breast cancer screening with either triennial MRI or annual mammography, 2.5M in each group, over 30 years.

Statistical Tests:

Expected recall rates, BI-RADS 3, BI-RADS 4/5 cases and cancer detection rates were determined from published literature with calculated aggregate costs including resultant diagnostic/follow-up imaging and biopsies.

Results:

Baseline screening of 2.5M women with breast MRI cost $1.6 billion (B), 3× higher than baseline mammography screening ($0.54B). With subsequent screening, MRI screening is more cost-effective than mammography screening in 24 years ($13.02B vs. $13.03B). MRI screening program costs are largely driven by cost per MRI exam ($549.71). A second simulation model was performed based on MRI Medicare reimbursement trends using a lower MRI cost ($400). This yielded a cost-effective benefit compared to mammography screening in less than 6 years ($3.41B vs. $3.65B), with over a 22% cost reduction relative to mammography screening in 12 years and reaching a 38% reduction in 30 years.

Data Conclusion:

Despite higher initial cost of a breast MRI screening program for average-risk women, there is ultimately a cost savings over time compared with mammography. This estimate is conservative given cost–benefit of additional/earlier breast cancers detected by breast MRI were not accounted for.

Breast cancer remains the most common noncutaneous cancer affecting women in the United States, with over 200,000 women diagnosed and over 40,000 breast cancer deaths in 2014.1 Breast cancer screening with mammography decreases breast cancer mortality,2–4 but has limitations, with an interval cancer rate of 30–50% and decreasing sensitivity as breast density increases.5–8 While breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrates better sensitivity for breast cancer detection, it is not the standard of care for screening average-risk women, with MRI primarily recommended for those with a 20% or greater lifetime risk of developing breast cancer.9

A recent study by Kuhl et al8 demonstrated supplemental MRI screening in women at average risk for breast cancer with normal mammograms improves early diagnosis of clinically relevant breast cancers, with an average supplemental cancer detection rate of 15.5 per 1000 cases and no interval cancers. These results are similar to the American College of Radiology (ACR) Imaging Network 6666 trial when a single round of MRI screening of women with elevated risk demonstrated an additional 14.8 cancers per 1000 cases.10 In the Kuhl et al study all cancers were visualized on MRI and none were seen with mammography alone, suggesting that MRI could potentially be a standalone screening modality for average-risk women.

Screening high-risk women with breast MRI has been shown to be cost-effective, with increasing cost-effectiveness with increasing breast cancer risk.11,12

However, cost is considered a major limitation to mass population screening with breast MRI. Our purpose was to perform a cost–benefit analysis of a breast cancer screening program of average-risk women utilizing MRI compared with mammography.

Materials and Methods

Monte Carlo Simulation

The Monte Carlo method, initially published in 1949 by Los Alamos National Laboratory physicists, simulates a process by iteratively repeating a computation with random variation of identified uncertainties within the modeled constraints.13,14 This method enables modeling of complex scenarios, such as outcomes in a simulated cohort of patients, which may be otherwise difficult to mathematically compute.15 Possible events for an individual patient are determined and then probabilities for each possible outcome are defined from the literature. A given event can lead to multiple other events, simulating a patient’s clinical path. This approach utilizes a probability distribution for an event that can be estimated from a number of input variables and samples the event several times.13,14 With large numbers of iterations the Mote Carlo simulation converges to an approximate result.13,14

Model Design

An Institutional Review Board (IRB)-exempt Monte Carlo simulation was developed to compare 5 million (M) average-risk women undergoing breast cancer screening with either triennial MRI or annual mammography, 2.5M in each group, over a 30-year period beginning at age 40. Performance of mammography every year is based on current ACR and Society of Breast Imaging guidelines.16 Breast MRI every 3 years is based on a recent study showing no interval cancers in an average-risk group undergoing screening MRI at variable intervals (12–36 months) with an average 34.9 months (median 37.5 months) until occurrence of an incident breast cancer.8

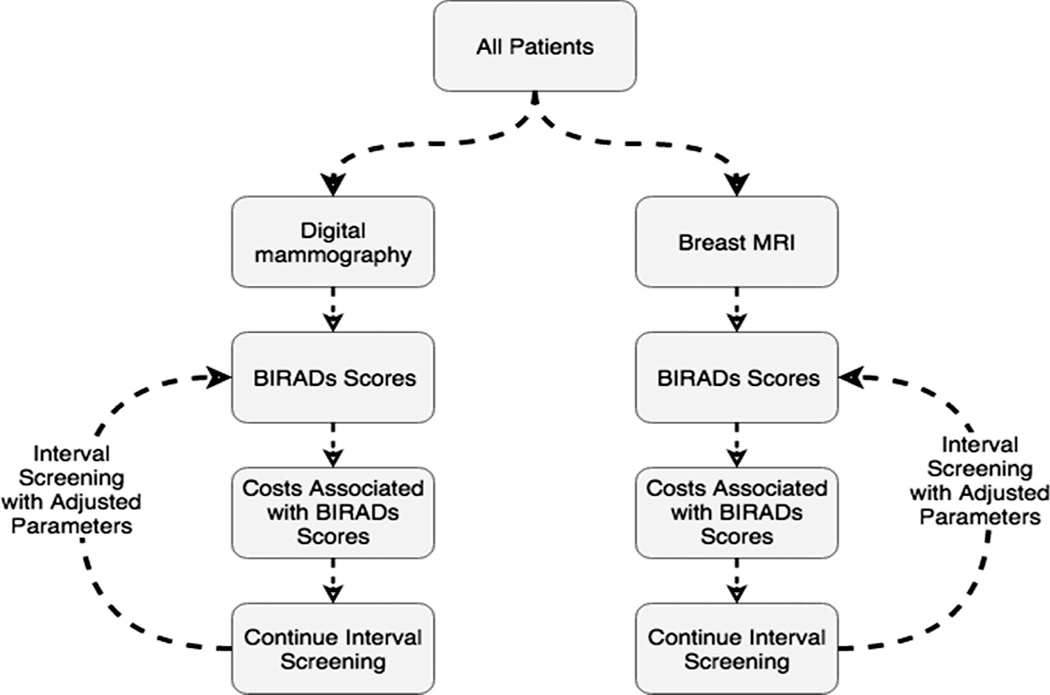

A model schematic was designed based on possible BI-RADS assessments and potential outcomes with each round of screening (Fig. 1). All required parameters for this simulation were identified from published literature (Table 1).

FIGURE 1:

Monte Carlo simulation model schematic based on possible BI-RADS assessments and potential outcomes with each round of screening of 5M women, 2.5M with mammography and 2.5M with MRI, over a 30-year period.

TABLE 1.

| Prevalence screen | Incidence screen | |

|---|---|---|

| Breast MRI | ||

| BI-RADS 1 or 2 | 88% | 94.5% |

| BI-RADS 3 | 5.7% | 3.2% |

| BI-RADS 4 or 5 | 6.3% | 2.3% |

| Digital mammography | ||

| BI-RADS 0 | 9.8% | 9.8% |

| BI-RADS 1 or 2 | 86.1% | 86.1% |

| BI-RADS 3 | 2.3% | 2.3% |

| BI-RADS 4 or 5 | 1.8% | 1.8% |

Monte Carlo simulation parameters for prevalence and incidence screening were identified from the published literature to obtain the expected frequency of each outcome.

To obtain the expected frequency of each outcome for required model variables, such as recall rates, BI-RADS 3, and BI-RADS 4/5 assessments, a literature search was performed with articles selected based on journal impact factor and relevance to digital mammography and breast MRI screening. Medicare reimbursement rates were utilized to calculate input variable costs (Table 2).17

TABLE 2.

Medicare Reimbursement Rates Utilized to Calculate Input Variable Costs (Ref.17)

| Exam | Medicare rates |

|---|---|

| MRI breast, bilateral | $549.71 |

| Mammogram 2D, screening bilateral | $138.17 |

| Mammogram 2D, diagnostic bilateral | $171.19 |

| Mammogram 2D, diagnostic unilateral | $134.94 |

| Ultrasound, limited unilateral | $90.36 |

| Stereotactic-guided core needle biopsy | $704.85 |

| Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy | $683.68 |

| MRI-guided core needle biopsy | $1038.62 |

Model Implementation

Models were schematically designed to estimate costs associated with mammography screening vs. breast MRI screening for 5M women, 2.5M in each group, over a 30-year period. 100% compliance with screening was assumed. Patients were assigned BI-RADS scores based on probability parameters from the literature. Probability parameters were used for the initial screening of patients (“prevalence screening”) and for subsequent screening intervals (“interval screening”). For BI-RADS 3 MRI cases, one short-term follow-up MRI was considered sufficient, as was seen in 98.3% of patients in a recent study.8 For BI-RADS 4 or 5 MR cases, it was assumed all had MRI-guided biopsy. For BI-RADS 4 or 5 mammography cases, a biopsy cost of $694.26 was used for calculations, the average cost of an ultrasound and stereotactic biopsy.

This model was implemented in the R programming language using a probability sampling step at each point in the model. Total cost was then computed by multiplying the costs for each event by the event frequency. Expected recall rates, BI-RADS 3, BI-RADS 4/5 cases, and cancer detection were determined from published literature with calculated aggregate costs including resultant follow-up/diagnostic imaging and biopsies.

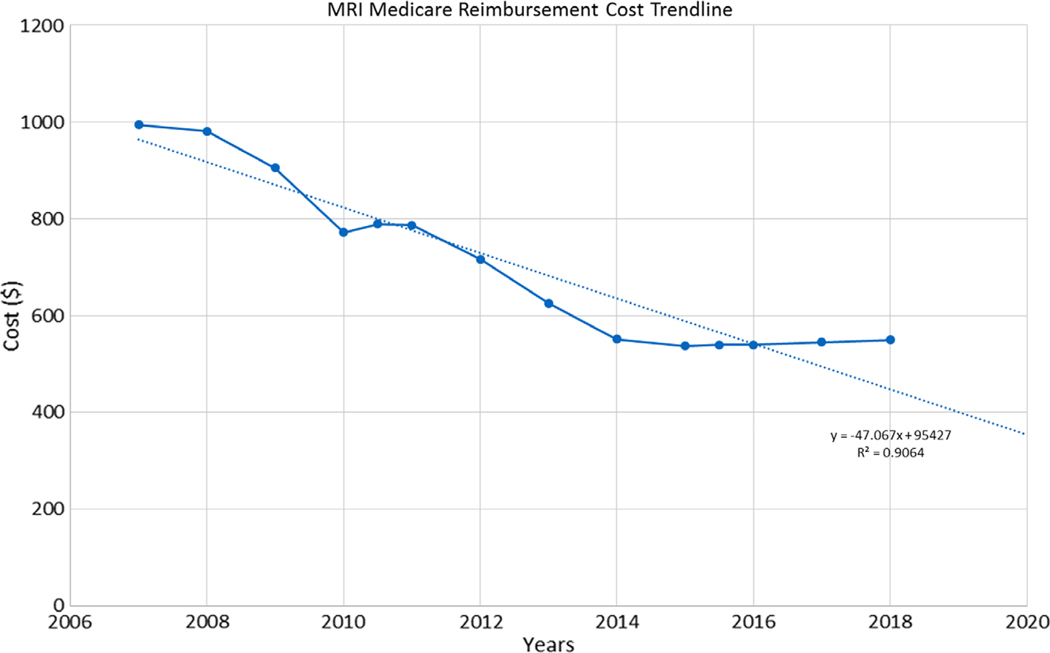

Medicare reimbursement rates for breast MRI are noted to be decreasing over time (Fig. 2); thus, the simulation was repeated utilizing a lower breast MRI cost of $400 to examine the effect of MRI cost on overall screening program cost.

FIGURE 2:

Medicare reimbursement rate for breast MRI. Solid blue line indicates cost of MRI over time. Trend line (dotted line) is calculated based on the generated formula (y = –47.067x + 95427; R2 = 0.9064).

Results

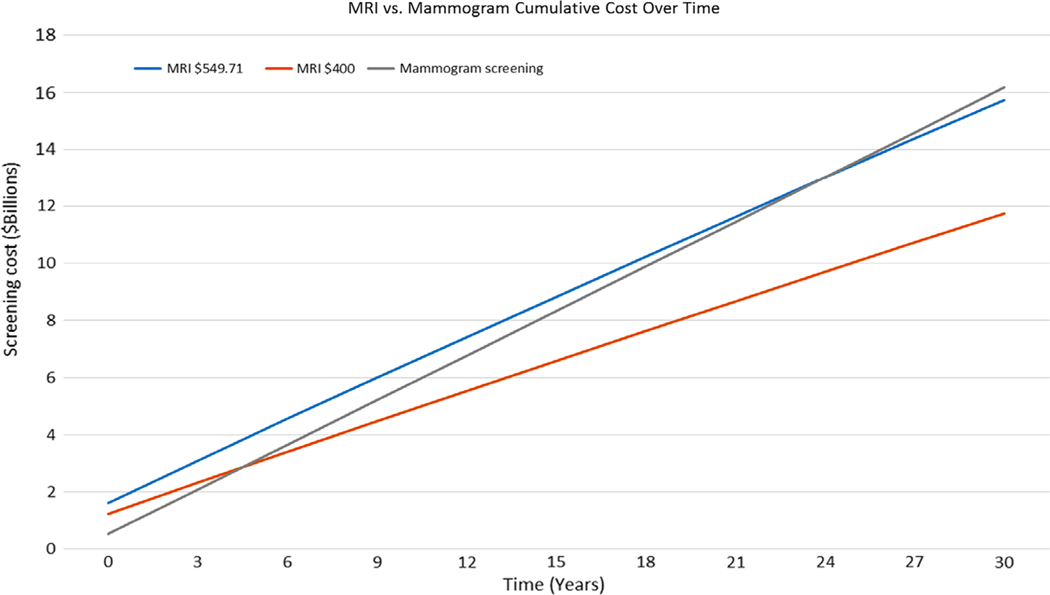

The initial cost of screening 2.5M women with breast MRI was $1.6 billion (B), 3× higher than screening 2.5M women with mammography ($0.54B). The average cost per patient prevalence screen and 95% confidence interval were calculated for the simulated MRI arm ($640, $608–$672) and simulated mammography arm ($216, $205.2–$226.8). With subsequent screening, the aggregate cost of MRI screening will be more cost-effective than mammography screening in 24 years ($13.02B vs. $13.03B) (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3:

Cumulative cost over time comparing MRI vs. mammography screening of 5M women, 2.5M in each group. At $549.71 per MRI, the MRI screening program becomes more cost-effective at year 24, where the blue solid line crosses the gray line. At $400 per MRI, the MRI screening program becomes more cost-effective at year 4.8, where the orange solid line crosses the gray line.

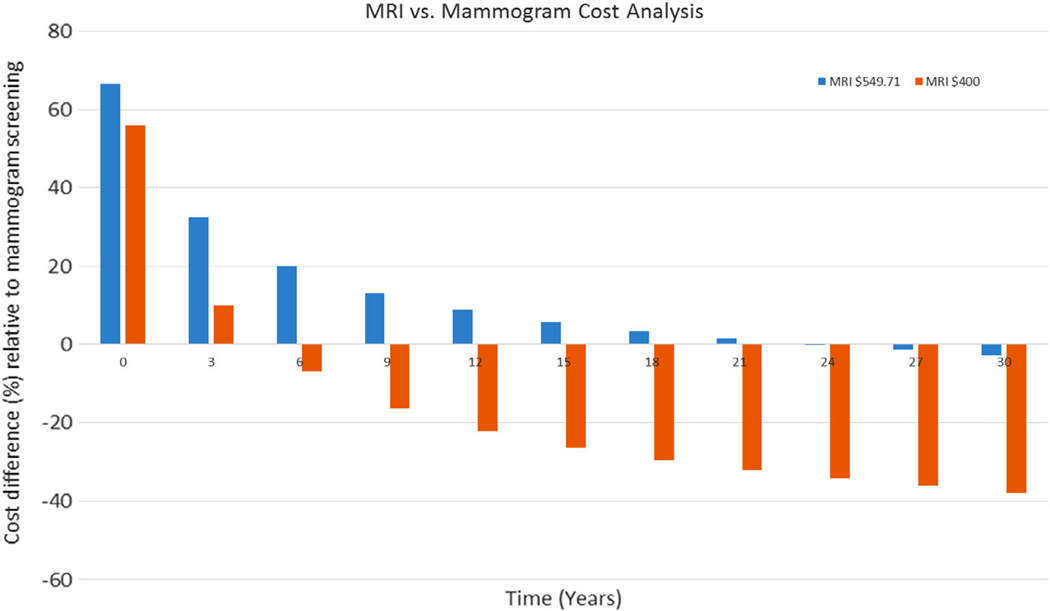

The largest driver of cost for the MRI screening program was the cost per MRI exam ($549.71). Using a lower MRI cost of $400 per exam, based on Medicare reimbursement trends, yielded a cost-effective benefit compared with mammography screening in less than 6 years ($3.41B vs. $3.65B at 6 years), with over a 22% cost reduction relative to mammographic screening in 12 years and reaching a 38% cost reduction in 30 years (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4:

Cost analysis comparison between mammogram and MRI screening program. Initially, the mammography screening is up to 66.6% more cost-effective than MRI screening. However, over time, MRI screening is more cost-effective, especially with lower MRI cost ($400, orange bar) showing over 22% cost reduction relative to mammography screening in 12 years and reaching a 38% reduction in 30 years.

Discussion

Mass population screening for breast cancer is expensive18 but despite the initial cost of a breast MRI screening program it becomes more cost-effective than mammography over time. Breast MRI costs largely drive how long a screening program must be in place before MRI is more cost-effective than mammography for breast cancer screening of average-risk women. Probably benign BI-RADS 3 cases necessitating short interval follow-up and biopsy recommendations, BI-RADS 4 and 5 cases, contribute to cost due to nonscreening imaging studies and biopsies performed. In clinical practice the rates of such assessments vary between radiologists and radiologist groups; thus, in practice, costs may vary depending on the specific radiologist.

In addition to cost savings over time, breast cancer screening with MRI may enable longer intervals between screening than mammography. An optimal screening interval is in part determined by the interval cancer rate, those breast cancers diagnosed after a normal screening study and before the next routine screen. Compared to screen detected cancers, interval cancers have a worse tumor prognosis, biomarker profile, and survival outcome. Following a normal mammogram, interval breast cancer rates have been reported to be 8.4–21.1 per 10,000 screens, with the majority of studies based on biennial screening with a larger proportion of interval cancers in the second year.19 This interval cancer rate supports an annual mammography screening recommendation by multiple medical societies.16,20

In contrast, Kuhl et al demonstrated after a negative MRI screening study, on average, the first screening diagnosis of breast cancer was not made until almost 3 years later, longer than that observed with mammography screening.8,21 This suggests the screening interval for MRI may be longer than that for mammography while maintaining a low rate of interval cancers, an area of needed research to validate these results. We chose a simulation incorporating an MRI screening interval of every 3 years; however, further study is needed to determine the optimal MR screening interval for average-risk women.

Screening with breast MRI demonstrates improved sensitivity for cancer detection relative to mammography.22–24 Cancer diagnosis at an earlier stage can decrease morbidity and treatment costs, with more lives saved. Our cost model provides conservative estimates, as we did not account for treatment cost savings when breast cancer is diagnosed earlier and the productivity costs of cancer mortality.25 Treating cancer patients diagnosed early is 2–4 times less expensive than treating those diagnosed at more advanced stages.25,26 Further expansion of this model accounting for productivity and treatment costs would likely demonstrate earlier cost savings for an MRI screening program.

The detection of additional cancers with MRI may raise concerns for potential overdiagnosis of breast cancer; however, Kuhl et al demonstrate additional cancers detected in average-risk women on breast MRI were small (median size, 8 mm), mostly node-negative (93.4%), and were dedifferentiated high-grade lesions in almost half the cases.8 Additional studies are warranted to validate these results.

In addition to cost, lengthy exam time is cited as a limitation to mass population screening with MRI; however, current research utilizing abbreviated MRI protocols may significantly shorten image acquisition time and radiologist interpretation time without compromising sensitivity for breast cancer detection.27–29 Decreased exam times may also decrease the cost associated with MRI. As we demonstrate in our model, decreasing the cost associated with MRI to $400, from $549.71, yielded a cost-effective benefit compared with mammography screening in less than 6 years ($3.41B vs. $3.65B).

While MRI has the benefit of no radiation exposure, current protocols rely on intravenous contrast for cancer diagnosis. The recent literature has reported long-term gadolinium deposition in the brain of uncertain clinical significance.30 A triennial screening model would help minimize gadolinium exposure with repeated long-term MR screening.

Limitations of our study include those of all simulation models that are based on multiple assumptions and estimates, all obtained from peer-reviewed literature, which can be challenging to validate. Our model is relatively simple and could be refined by including more factors. The simplicity of the model is intended to be a starting point, with future clinical studies providing data to better inform and shape a more complex model in the future. Cost estimates may range significantly with utilization of Medicare reimbursement rates vs. private payers. As discussed, the cost savings associated with earlier cancer diagnosis/treatment with MR was not incorporated in our model. Additional assumptions may also contribute to our model overestimating the cost of an MRI screening program. For example, for MR screen detected BI-RADS 4 lesions it was assumed all patients had MRI-guided biopsies rather than a less expensive ultrasound-guided biopsy of a sonographic correlate. Our study relies on literature from the US and Europe, and additional modeling studies would be necessary in populations with lower breast cancer incidence rates. There are limited studies examining screening MR in average-risk women and additional studies are warranted to facilitate more accurate modeling.

Another study limitation includes assuming 100% compliance in both screening groups, as this is typically not possible in a true clinical practice setting. While there are data available for mammography screening compliance, there are no data on compliance with MRI screening every 3 years for average-risk women. Studies examining compliance with mammography screening recommendations show variable rates of 50–80%.35 A study of high-risk women seen by a breast specialist demonstrates MR screening compliance rates of 88%.36 Lack of MR compliance data applicable to average-risk women limits our ability to incorporate compliance rates into our estimates. In order to facilitate cost comparisons we presumed compliance would be the same in both groups.

In conclusion, despite the higher initial cost of a breast MRI screening program, there is ultimately a cost savings depending on MRI cost. A breast MRI screening program should not be dismissed based on high initial costs, as long-term cost simulations demonstrate a potential cost savings relative to mammography. This estimate is conservative given the cost–benefit of additional/earlier breast cancers detected by breast MRI was not accounted for in this model.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: MSK Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant; Contract grant number: P30 CA008748.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. United States cancer statistics 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/index.htm. Accessed February 14, 2018.

- 2.Alexander FE, Anderson TJ, Brown HK, et al. The Edinburgh randomized trial of breast cancer screening: Results after 10 years of follow-up. Br J Cancer 1994;70:542–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Autier P, Boniol M, Smans M, et al. Statistical analysis in Swedish randomized trials on mammography screening and in other randomized trials on cancer screening: A systemic review. J R Soc Med 2015;108: 440–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro S Periodic screening for breast cancer: The HIP randomized controlled trial. Health Insurance Plan. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1997;22: 27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freer PE. Mammographic breast density: Impact on breast cancer risk and implications for screening. RadioGraphics 2015;35:302–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carney PA, Miglioretti DL, Yankaskas BC, et al. Individual and combined effects of age, breast density, and hormone replacement therapy use on the accuracy of screening mammography. Ann Intern Med 2003;138: 168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerlikowske K, Hubbard RA, Miglioretti DL, et al. Comparative effectiveness of digital versus film-screen mammography in community practice in the United States: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology 2017; 283:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mainiero MB, Lourenco A, Mahoney MC, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria breast cancer screening. J Am Coll Radiol 2013;10:11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, et al. , ACRIN 6666 Investigators. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast-cancer risk. JAMA 2012;307:1394–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plevritis SK, Kurian AW, Sigal BM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with breast magnetic resonance imaging. JAMA 2006;295:2374–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taneja C, Edelsberg J, Weycker D, Guo A, Oster G, Weinreb J. Cost effectiveness of breast cancer screening with contrast-enhanced MRI in high-risk women. J Am Coll Radiol 2009;6:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metropolis N, Ulam S. The Monte Carlo method. J Am Stat Assoc 1949; 44:335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loving VA, Edwards DB, Roche KT, et al. Monte Carlo simulation to analyze the cost-benefit of radioactive seed localization versus wire localization for breast-conserving surgery in fee-for-service health care systems compared with accountable care organizations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014;202:1383–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robert CP. Monte Carlo methods. Wiley Online Library; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.www.acr.org. ACR Position Statements: Breast Cancer Screening for Average Risk Women: Recommendations from the ACR Commission on Breast Imaging September 22, 2017. Accessed March 3, 2018.

- 17.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Physician Fee Schedule look-up. www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule Accessed February 27, 2018.

- 18.Direct and Indirect Economic Costs of Illness by Major Diagnosis, U.S., 2008. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Fact Book, February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houssami N, Hunter K. The epidemiology, radiology and biological characteristics of interval breast cancers in population mammography screening. NPJ Breast Cancer 2017:3:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee C, Moy L, Friedewald S, et al. Harmonizing breast cancer screening recommendations: Metrics and accountability. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2018;210:241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michaelson J, Satija S, Moore R, et al. The pattern of breast cancer screening utilization and its consequences. Cancer 2002;94:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bone B, Aspelin P, Brong L, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of MR mammography with histopathological correlation in 250 breasts. Acta Radiol 1996;37:208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heywang-Kobrunner SH, Viewhweg P, Heinig A, et al. Contrast-enhanced MRI of the breast: Accuracy, value, controversies, solutions. Eur J Radiol 1997;24:94–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Maschio A, Panizza P. Breast MR: State of the art. Eur J Radiol 1998; 27:250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley CJ, Yabroff KR, Dahman B, et al. Productivity costs of cancer mortality in the Unite States: 2000–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100: 1763–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kakushadze Z, Raghubanshi R, Yu W. Estimating cost savings from early cancer diagnosis. Data 2017;2:30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuhl CK, Schrading S, Strobel K, Schild HH, Hilgers RD, Bieling HB. Abbreviated breast magnetic resonance imaging: First postcontrast subtracted images and maximum-intensity projection: A novel approach to breast cancer screening with MRI. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2304–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mango VL, Morris EA, Dershaw DD, et al. Abbreviated protocol for breast MRI: Are multiple sequences needed for cancer detection? Eur J Radiol 2015;84:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heacock L, Melsaether AN, Heller SL, et al. Evaluation of a known breast cancer using an abbreviated breast MRI protocol: Correlation of imaging characteristics and pathology with lesion detection and conspicuity. Eur J Radiol 2016;85:815–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenkinksi RE. Gadolinium retention and deposition revisited: How the chemical properties of gadolinium-based contrast agents and the use of animal models inform us about the behavior of these agents in the human brain. Radiology 2017;285:721–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenberg RD, Yankaskas BC, Abraham LA, et al. Performance bench-marks for screening mammography. Radiology 2006;241:55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baum JK, Hanna LG, Acharyya S, et al. Use of BI-RADS 3-Probably Benign Category in the American College of Radiology Imaging Network Digital Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial. Radiology 2011;260: 61–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poplack SP, Tosteson AN, Grove MR, et al. Mammography in 53,803 women from the New Hampshire mammography network. Radiology 2000;217:832–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Donoghue C, Eklund M, Ozanne EM, et al. Aggregate cost of mammography screening in the United States: Comparison of current practice and advocated guidelines. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onitilo AA, Engel JM, Liang H, et al. Mammography utilization: Patient characteristics and breast cancer stage at diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;201:1057–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eshani S, Strigel RM, Pettke E, et al. Screening magnetic resonance imaging recommendations and outcomes in patients at high risk for breast cancer. Breast J 2015;21:246–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]