Abstract

Background

Although biceps tenodesis has been widely used to treat its pathologies, few studies looked at the objective evaluation of elbow strength after this procedure. The purpose of this study is to clinically evaluate patients submitted to long head of the biceps (LHB) tenodesis with interference screws through an intra-articular approach and analyze the results of an isokinetic test to measure elbow flexion and forearm supination strengths.

Methods

Patients who had biceps tenodesis were included in the study if they had a minimum follow-up of 24 months. Patients were excluded if they had concomitant irreparable cuff tears or previous or current contralateral shoulder pain or weakness. Postoperative evaluation was based on University of California–Los Angeles (UCLA) shoulder score and on measurements of elbow flexion and supination strength, using an isokinetic dynamometer. Tests were conducted in both arms, with velocity set at 60º/s with 5 concentric-concentric repetitions.

Results

Thirty-three patients were included and the most common concomitant diagnosis were rotator cuff tear (69%) and superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesions (28%). The average UCLA score improved from 15.1 preoperatively to 31.9 in the final follow-up (P < .001). Isokinetic tests showed no difference in peak torque between the upper limbs. One patient had residual pain in the biceps groove. None of the patients had Popeye deformity. UCLA score and follow-up length did not demonstrate correlation with peak torque.

Conclusion

Arthroscopic proximal biceps tenodesis with interference screw, close to the articular margin, yielded good clinical results. Isokinetic tests revealed no difference to the contralateral side in peak torque for both supination and elbow flexion.

Keywords: Shoulder, biceps tendon, tenodesis, elbow strength, isokinetic evaluation, arthroscopy

The long head of the biceps (LHB) tendon may be an important cause of shoulder pain.45, 48 This may range from a simple inflammatory process (tenosynovitis) to progressive tendinosis resulting in complete tendon rupture.41 The association between rotator cuff tears and LHB tendinosis has been described,3 and studies show that larger tears correlate to a higher prevalence of LHB tendon degeneration.16,60 Also, LHB instability (luxation and subluxation) may occur, usually associated with lesions of the biceps pulley and/or rotator cuff tears, mainly the subscapular tendon.53 Superior labrum tears involving the origin of the LHB (superior labrum anterior to posterior [SLAP] lesions) have also been implicated as causes of shoulder pain.2,3,9

In general, conservative treatment may be indicated initially, even though supported by little evidence in the literature.3,41 Among surgical options, LHB tenotomy and tenodesis are the most common. Both seem equally efficient in the resolution of pain, although tenotomy may cause residual deformity (Popeye sign) and strength impairment.3,29,59 For this reason, tenodesis has been preferred in younger and more active subjects.26 Epidemiologic studies have shown that the number of such procedures has risen between 2007 and 2011, most performed in individuals between ages 30 and 59 years.52,55 Multiple techniques have been described for LHB tenodesis both on soft tissue12,15,23 and bone, in which tendon fixation may be obtained with transosseous tunnels,38 “keyholes,”19 cortical buttons,39 suture anchors,10,17,45, 46, 47 and interference screws.5

Originally described by Boileau et al,5 interference screw tenodesis has demonstrated biomechanical superiority to other fixation methods in comparative studies.20,33, 34, 35,43,49 Lo and Burkhart24 introduced a modification to the technique, in which interference screw tenodesis was performed on the proximal portion of the intertubercular groove, on the edge of the articular surface of the humerus using an intra-articular view. This location is controversial, however, because residual pain in the intertubercular groove has been reported and attributed to an increase in LHB strain57 and to maintenance of a portion of unhealthy tendon in the intertubercular groove.25,40

The objectives of this study are, therefore, to clinically evaluate patients submitted to LHB tenodesis with interference screws through an intra-articular approach and analyze the results of an isokinetic test to measure elbow flexion and forearm supination strengths.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient selection

A retrospective case series was carried out, and patients who had arthroscopic LHB tenodesis with interference screw, performed between 2009 and 2014, were identified from the hospital surgical records. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) older than 18 years and (2) minimum follow-up of 24 mouths. Patients were excluded if they presented (1) irreparable injuries of rotator cuff muscles in ipsilateral shoulder and (2) previous or current contralateral shoulder pain. The main indication for surgery was symptomatic tendinopathy of LHB, observed through magnetic resonance imaging and confirmed with arthroscopic procedure. Besides that, patients older than 40 years with SLAP injuries unresponsive to conservative medical treatment were also an indication for the procedure. The research was approved by the local ethics committee, and all volunteers read and signed an informed consent form, in which the experimental goals and conditions were fully described in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Surgical technique

All LHB tenodesis had been performed arthroscopically, in beach chair position, under general anesthesia and interscalene brachial plexus block using nerve stimulator. A 30º scope was routinely used, and when concomitant repair of large subscapularis tendon tear was needed, a 70º scope was used. After joint inspection, the anatomopathologic status of biceps muscle was labeled as shown in Table I. A braided polyester suture (Ethibond Excel no. 2; Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA) was passed through biceps tendon and a tenotomy was carried on at the superior labrum. When the tendon was brought outside through the anterior portal a Krackow suture was made on the LHB using strong unabsorbable polyester sutures (FiberWire no. 2, Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) and its diameter was measured in millimeters with a specific measure instrument (Fig. 1). The suture limbs were passed through the cannulated driver so that the LHB stump gets in contact with the driver's extremity. Next, the guide wire was inserted in the proximal region of the intertubercular groove, close to the humeral articular cartilage, and a hole was made using a cannulated drill with a diameter same as the tendon's (Fig. 2). Then the LHB was inserted into the bone socket, and the cannulated screw (Bio-Tenodesis Screw; Arthrex) was slipped through the same driver (Fig. 3). Lastly, the suture limbs were either cut and removed from the joint or used in the repair of a subscapularis tendon tear.

Table I.

LHB intraoperative anatomopathologic classification

| Type | LHB classification |

|---|---|

| 1 | Normal |

| 2 | Tendinitis |

| 3 | Fibrillation |

| 4 | Longitudinal tear |

| 5 | Partial tear |

| 6 | SLAP lesion |

LHB, long head of the biceps; SLAP, superior labrum anterior to posterior.

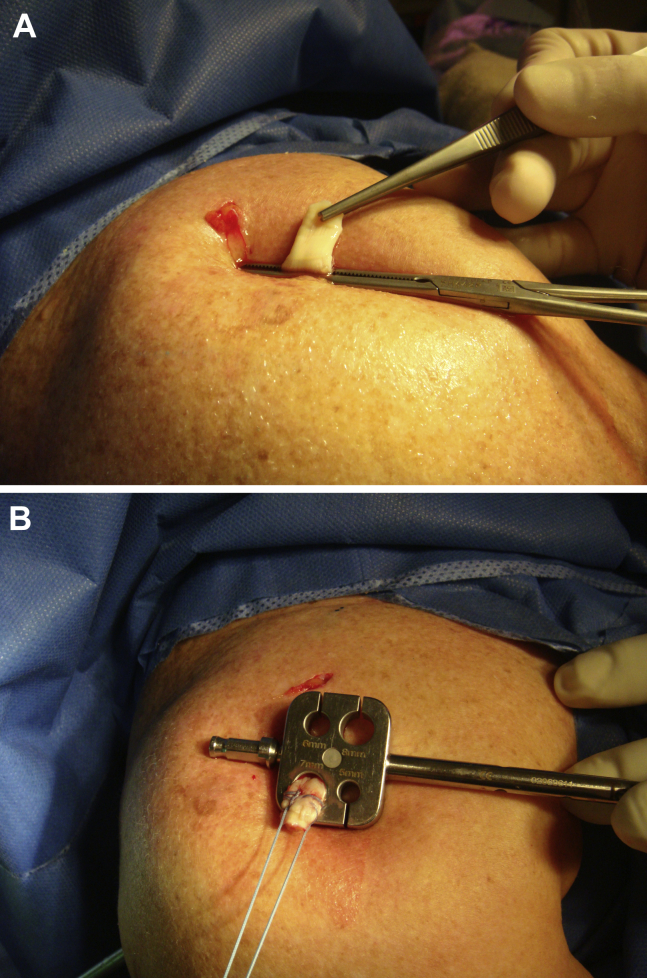

Figure 1.

Right shoulder, superolateral view. (A) Biceps tendon is exposed through the anterior portal and held with a clamp. (B) Krackow suture is made and the tendon diameter is measured.

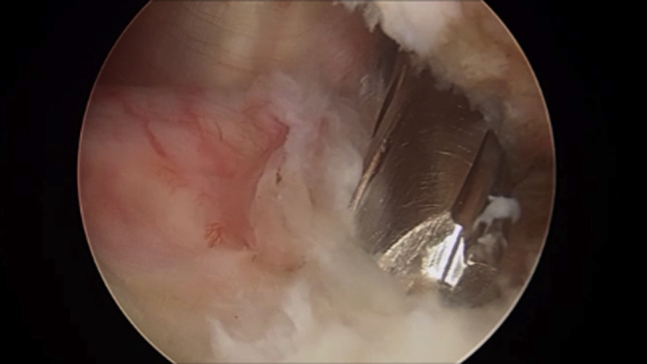

Figure 2.

A bone socket is made using a cannulated drill.

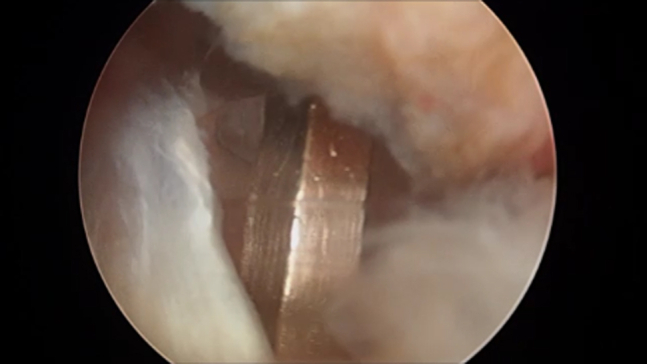

Figure 3.

Biceps tendon is placed inside the bone socket and interference screw slides through the driver into the bone socket.

Postoperative care

When isolated biceps tenodesis was carried on, without concomitant major procedures, the postoperative program was as follows: sling for 3 weeks; active elbow, wrist, and hand motion from the first day after surgery; and shoulder passive elevation and external rotation started 1 week after surgery. After sling removal, patients were referred to physiotherapy to regain range of movement. Biceps-strengthening exercises started at 12 weeks after the surgery, although rotator cuff strengthening was allowed earlier, at 8 weeks. When biceps tenodesis was made in conjunction with other major procedure(s), the rehabilitation program was dictated by the one that requires the longest recovery period. For instance, when a biceps tenodesis was made concomitant with the repair of a massive rotator cuff tear, the immobilization period was longer and rotator cuff–strengthening exercises were introduced after 12-16 weeks.

Clinical and isokinetic evaluation

The clinical outcomes were evaluated using the University of California–Los Angeles (UCLA) shoulder score,1 measured in pre- and postoperative moments. The patient's shoulders were examined by the same physician looking for signs of impairment of LHB, as pain on direct palpation of intertubercular groove and biceps belly deformity. The muscular torque was measured using an isokinetic dynamometer (CSMI; Humac Norm, Stoughton, MA, USA). The patient was positioned as manufacturer's determinations to measurement of supination and elbow flexion. The flexion tests were performed with both neutral and supinated forearm positions. In all tests, procedures were conducted in both arms, with velocity set at 60º/s with 5 concentric-concentric repetitions. Prior to evaluation, familiarization and warmup procedures were conducted. The arm and movements order were randomly assigned. The peak torque achieved was calculated and normalized by total body weight.

Statistics

The involved and contralateral limbs were compared using separate paired t tests for peak torque and peak work, as the pre- and postoperative UCLA scores. Cohen effect size was used to express the magnitude of difference in assessed comparisons. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for pre-UCLA vs. post-UCLA, post-UCLA vs. follow-up, and between pre-UCLA, post-UCLA, and follow-up with peak torque and peak work values. All calculations were conducted using SPSS, version 19 (IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA), and all graphs were produced with GraphPad Prism, version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was predetermined as 5%.

Results

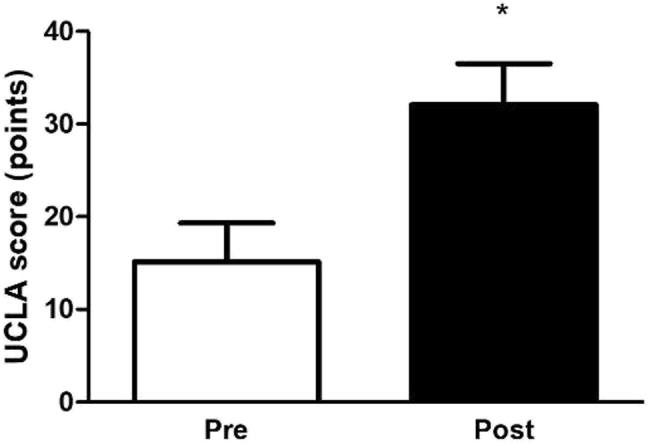

Thirty-three patients took part in the study (age: 50 ± 9.8 years; height: 170.23 ± 7.06 cm; weight: 83.55 ± 11.72 kg). The dominant upper limb was the involved limb in 69% of cases. The most common associated diagnoses were rotator cuff injury (69%), SLAP lesion (28%), and anterior labrum injury (20%). The mean time of follow-up was 37.9 months. More detailed and other demographic data were displayed in Table II. The average UCLA score improved from 15.1 preoperatively to 31.9 in the final follow-up (P < .001, d = 4.04; Fig. 4). A total of 9 patients reported palpation pain at the intertubercular groove, although only 1 subject reported occasionally spontaneous pain. Another patient developed postsurgery joint stiffness, and had a good outcome following conservative treatment of 8 months. None of the patients showed biceps muscle belly deformity.

Table II.

Demographic data

| Variable | Patients |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Man | 24 |

| Woman | 9 |

| Age, yr | |

| Mean (variation) | 48 (27-69) |

| Laterality: limb dominance | |

| Right | 32 |

| Left | 1 |

| Laterality: involved limb | |

| Right | 23 |

| Left | 10 |

| Rotator cuff tear | |

| Complete | 11 |

| Partial | 7 |

| Total | 18 |

| Chondropathy | |

| Yes | 7 |

| No | 25 |

| Labrum repair | |

| Yes | 13 |

| No | 20 |

| Follow-up, mo | |

| Mean (variation) | 38 (24-80) |

Figure 4.

UCLA scores measured in pre- and postsurgery (mean ± SD). UCLA, University of California–Los Angeles functional scale; Pre, presurgery; Post, postsurgery; SD, standard deviation. ∗Significantly different from presurgery score (P < .001, d = 4.04).

Regarding the isokinetic tests, there was no significant difference between the involved and contralateral limbs (Table III). There were no significant correlations between postoperative UCLA and follow-up length (r = –0.017, P = .924) and between pre- and postsurgery UCLA (r = 0.176, P = .329). Similarly, UCLA and follow-up did not demonstrate correlation with peak torque (Table IV).

Table III.

Peak torque measured in an isokinetic dynamometer at 60°/s

| Peak torque, Nm/kg, mean ± SD |

P value | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involved | Contralateral | |||

| FlexN | 0.46 ± 0.17 | 0.45 ± 0.16 | .623 | 0.06 |

| FlexS | 0.48 ± 0.18 | 0.48 ± 0.18 | .937 | 0.00 |

| Sup | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | .111 | 0.25 |

FlexN, elbow flexion with forearm neutral; FlexS, elbow flexion with forearm neutral supination; Sup, forearm supination; SD, standard deviation; d, Cohen effect size.

Table IV.

Correlation analyses between UCLA and follow-up with torque measurements of involved limb

| Presurgery UCLA score |

Postsurgery UCLA score |

Follow-up, mo |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | |

| FlexN | 0.355∗ | .042 | –0.09 | .959 | 0.194 | .280 |

| FlexS | 0.339 | .054 | 0.087 | .628 | 0.143 | .427 |

| Sup | 0.163 | .364 | 0.126 | .485 | 0.075 | .680 |

FlexN, elbow flexion with forearm neutral; FlexS, elbow flexion with forearm neutral supination; Sup, forearm supination; UCLA, University of California–Los Angeles functional scale.

Significantly correlated (P < .05).

Discussion

This study has shown that arthroscopic biceps tenodesis leads to good clinical results and preserves maximum flexion and supination strength of the elbow. All the patients were operated on by the same surgeon and underwent postoperative evaluation by an independent examiner.

Most patients included in this study (69%) had associated rotator cuff tears along with the biceps tendinopathy, and frequently, this was the main indication for surgery. In fact, Naudi et al31 have shown that 90% of patients submitted to rotator cuff repairs have LHB tendon histologic alterations. Also, Jacquot and Boileau16 have found static and dynamic macroscopic alterations on arthroscopic inspection of the LHB tendon in 82% of the 378 patients submitted to rotator cuff repairs in their study. SLAP lesions were found in 28% of cases, also featuring as an important indication for LHB tenodesis. Some authors have demonstrated better results with LHB tenodesis compared with superior labrum repair,4,9,14,54,56 with even worse results for repair in older patients.54 In spite of this, there is no consensus about a minimum age to decide between labrum repair and LHB tenodesis. In our series, the youngest patient was a 27-year-old male bodybuilder who presented with a superior and anterior labrum lesion. A biceps tenodesis was performed considering the patient's high demand and the already present macroscopic tendinopathy alterations.

If, on one hand, there is a trend to perform LHB tenodesis in younger patients, this tendency is also seen in the treatment of older patients. Even though recent epidemiologic studies confirm that most of these procedures are performed in patients 30-60 years old, there was a significant increase in LHB tenodesis performed in patients older than 60 years.52,55 That is also our experience, because a rising number of these patients practice sports regularly and are concerned with aesthetic issues derived from a tenotomy without tenodesis. Although some studies have shown similar functional results with both tenotomy and tenodesis of the LHB, strength deficit is reported after biceps tenotomy. The et al50 revealed significant strength deficit for both supination and elbow flexion in long-term follow-up of patients submitted to tenotomy, compared with the contralateral side. Lee et al21 showed that both tenotomy and tenodesis patients had similar improvements of functional scores after surgery. However, the supination strength was significantly lower in patients submitted to tenotomy compared with those with a tenodesis. Moreover, the Popeye deformity was 3 times more common in the tenotomy patients. Recently, García-Rellán et al11 reported functional and strength improvements in both tenotomy and tenodesis patients. However, the elbow flexion strength of the patients submitted to tenotomy did not reach that of the contralateral side.

In this study, our clinical evaluation was based on the UCLA shoulder score1 and on physical examination of the operated shoulder. The mean postoperative score was more than double the preoperative one, showing great functional recovery. Even though only 1 patient reported sporadic localized shoulder pain in the intertubercular groove, precipitated by muscle strain, 9 patients (27%) reported pain when the bicipital groove was palpated on physical examination. This could be attributed to an increase in tension of the LHB tendon on the bicipital groove when intra-articular tenodesis is performed adjacent to the humeral head cartilage. Werner et al57 performed a biomechanical study that concluded that tenodesis with a proximal interference screw may increase LHB tension. For this reason, many advocate a more distal tenodesis, suprapectoral or even subpectoral.7,13,18,27,28,30,37,51,56,61 Nevertheless, we agree with Denard et al,8 who has shown that a better LHB tendon length-tension relation recovery can be obtained with an interference screw adjacent to the articular margin of the humerus in a 25-mm-deep hole. Maybe the persistence of pathologic tendon tissue in the bicipital groove and not the tension increase per se is what precipitates pain on palpation.25,40 It is worth noting that the clinical relevance of this finding is minor, because only 1 of the 33 patients reported spontaneous local pain and 73% demonstrated no pain, not even on palpation. Although subpectoral biceps tenodesis is thought to produce less residual pain because the pathologic part of the biceps is removed, Gombera et al13 and Yi et al61 revealed no difference in outcomes of patients submitted to proximal or subpectoral tenodesis. Moreover, proximal biceps tenodesis have some advantages, including less surgical dissection (all arthroscopic method), easier revision surgery because of tendon preservation, and more accurate restoration of biceps tension. Also, subpectoral tenodesis is not free of complications, including severe ones, such as humerus fracture and nerve injuries.32,36

Although residual pain in the biceps groove is often reported after proximal biceps tenodesis, its actual incidence is not so clear. The largest series of biceps tenodesis available in the literature is that of Brady et al,6 which was entirely performed with the same technique as that reported in our article. In their article, the endpoint was not pain in the tubercular groove but revision surgery rate due to pain, which was 0.4%. Yi et al61 reported that 5.8% of their patients had tenderness in the bicipital groove at the final follow-up, but the authors did not mention if it was on palpation or spontaneous pain. Sanders et al40 showed that the revision rate was higher for patients who had tenodesis without opening of the transverse ligament. However, the percentage of patients with residual pain was not mentioned. None of our patients required revision surgery. Besides, only 1 of our patients (0.03%) reported occasional spontaneous pain in the bicipital groove. The other 8 patients denied having pain when asked about it, although they had mild tenderness on palpation of the biceps groove.

Per the clinical results, the isokinetic testing showed satisfactory results. Maximum strength (peak torque) on the operated side was equivalent to that on the contralateral side on both elbow flexion and supination. This finding is in agreement with previous reports,42,44,62 and indicates that no loss of elbow strength should be expected following a biceps tenodesis.

There are many materials and methods for performing an LHB tenodesis, including tenodesis to soft tissues12,15,23 and bony tenodesis without interference screws. Though Levin et al23 defended soft tissue tenodesis arguing that it better reproduces biceps tension, the Popeye deformity may occur in up to 35% of cases,12 which did not happen in this series. Complications with tenodesis with anchors and cortical buttons have also been described.22,39 Richards and Burkhart35 have shown in a biomechanical study that an interference screw tenodesis has significantly higher pullout strength than one performed with 2 anchors. Ozalay et al33 performed a biomechanical study comparing 4 techniques of biceps tenodesis and found the interference screw to be almost twice as strong as the fixation with suture anchors. Patzer et al34 biomechanically compared 4 arthroscopic techniques of biceps tenodesis and also found interference screws to have the higher ultimate load to failure. Although it is difficult to transfer the results of a biomechanical study to the clinical setting, these results should serve as a general guide when choosing a biceps tenodesis technique for our patients, especially those with higher demand in sports or heavy labor. Lee et al22 performed a retrospective study on patients undergoing concomitant rotator cuff repair and biceps tenodesis using suture anchors. After a 2-year follow-up period, they noticed a Popeye deformity in 12.9%. This high rate of failure in this clinical study may relate to the inferior performance of the suture anchors in biomechanical studies.

This study has some weakness. First, we have a relatively small sample, as we use other tenodesis techniques, both open and arthroscopic, in our institution. Also, some patients refused to go to the hospital for the isokinetic test, as most of them were completely asymptomatic. Nonetheless, the number of patients still allowed for a solid statistical analysis and reliable final results. Second, we did not have a control group. Instead, we used the contralateral limb as control. This decision was based on Wittstein et al's58 study, which showed that the dominant and nondominant upper extremities have similar peak torque and endurance for supination and flexion. The authors concluded that the contralateral upper extremity can be used as a matched control in the evaluation of postoperative biceps isokinetic strength and endurance without adjusting results for handedness.

Conclusions

Arthroscopic proximal biceps tenodesis with interference screw, close to the articular margin, yielded good clinical results. Isokinetic tests revealed no difference to the contralateral side in peak torque for both supination and elbow flexion.

Disclaimer

The authors, their immediate families, and any research foundations with which they are affiliated have not received any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article.

Footnotes

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Trauma and Orthopedics (document no. 39772314.0.0000.5273).

References

- 1.Amstutz H.C., Sew Hoy A.L., Clarke I.C. UCLA anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;155:7–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydin N., Sirin E., Arya A. Superior labrum anterior to posterior lesions of the shoulder: diagnosis and arthroscopic management. World J Orthop. 2014;5:344–350. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boileau P., Baqué F., Valerio L., Ahrens P., Chuinard C., Trojani C. Isolated arthroscopic biceps tenotomy or tenodesis improves symptoms in patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:747–757. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boileau P., Parratte S., Chuinard C., Roussanne Y., Shia D., Bicknell R. Arthroscopic treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions: biceps tenodesis as an alternative to reinsertion. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:929–936. doi: 10.1177/0363546508330127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boileau P., Krishnan S.G., Coste J.S., Walch G. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis: a new technique using bioabsorbable interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:1002–1012. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.36488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brady P.C., Narbona P., Adams C.R., Huberty D., Parten P., Hartzler R.U. Arthroscopic proximal biceps tenodesis at the articular margin: evaluation of outcomes, complications, and revision rate. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:470–476. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.David T.S., Schildhorn J.C. Arthroscopic suprapectoral tenodesis of the long head biceps: reproducing an anatomic length-tension relationship. Arthrosc Tech. 2012;1:e127–e132. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denard P.J., Dai X., Hanypsiak B.T., Burkhart S.S. Anatomy of the biceps tendon: implications for restoring physiological length-tension relation during biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:1352–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.04.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson J., Lavery K., Monica J., Gatt C., Dhawan A. Surgical treatment of symptomatic superior labrum anterior-posterior tears in patients older than 40 years: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1274–1282. doi: 10.1177/0363546514536874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foad A., Faruqui S., Hanna C.C. The modified norwegian method of biceps tenodesis. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;3:e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García-Rellán J.E., Sánchez-Alepuz E., Mudarra-García J. Increased fatigue of the biceps after tenotomy of the long head of biceps tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26:3826–3831. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godinho G.G., Mesquita F.A., França Fde O., Freitas J.M. “Rocambole-like” biceps tenodesis: technique and results. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;46:691–696. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30326-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gombera M.M., Kahlenberg C.A., Nair R., Saltzman M.D., Terry M.A. All-arthroscopic suprapectoral versus open subpectoral tenodesis of the long head of the biceps brachii. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1077–1083. doi: 10.1177/0363546515570024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gosselin P.O., Sirveaux F., Molé D., Parratte S., Boileau P. Désinsertions proximales du long bíceps (SLAP de type 2): réinsertion ou ténodèse sous arthroscopie? Rev Chir Orthop. 2007;93:S26–S29. doi: 10.1016/S0035-1040(07)79301-7. [Tears of the long head of the biceps at the superior labrum (type 2 SLAP): repair or tenodesis under athroscopy?] [in French] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goubier J.N., Bihel T., Dubois E., Teboul F. Loop biceps tenotomy: an arthroscopic technique for long head of biceps tenotomy. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3:e427–e430. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacquot P.N., Boileau P. Le long bíceps peut-il être sain dans les ruptures de la coiffe des rotateurs? Épidémiologie et comportement dynamique. Rev Chir Orthop. 2007;93:S30–S31. doi: 10.1016/S0035-1040(07)79389-3. [May the long head of the biceps be intact in patients with rotator cuff tears?] [in French] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaback L.A., Gowda A.L., Paller D., Green A., Blaine T. Long head biceps tenodesis with a knotless cinch suture anchor: a biomechanical analysis. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:831–835. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahlenberg C.A., Patel R.M., Nair R., Deshmane P.P., Harnden G., Terry M.A. Clinical and biomechanical evaluation of an all-arthroscopic suprapectoral biceps tenodesis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014:2. doi: 10.1177/2325967114553558. 2325967114553558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kany J., Guinand R., Amaravathi R.S., Alassaf I. The keyhole technique for arthroscopic tenodesis of the long head of the biceps tendon. In vivo prospective study with a radio-opaque marker. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusma M., Dienst M., Eckert J., Steimer O., Kohn D. Tenodesis of the long head of biceps brachii: cyclic testing of five methods of fixation in a porcine model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:967–973. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H.J., Jeong J.Y., Kim C.K., Kim Y.S. Surgical treatment of lesions of the long head of the biceps brachii tendon with rotator cuff tear: a prospective randomized clinical trial comparing the clinical results of tenotomy and tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:1107–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H.I., Shon M.S., Koh K.H., Lim T.K., Heo J., Yoo J.C. Clinical and radiologic results of arthroscopic biceps tenodesis with suture anchor in the setting of rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:e53–e60. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levin S.D., Wellman D.S., Liu C., Li Y., Ren Y., Shah N.A. Biomechanical strain characteristics of soft tissue biceps tenodesis and bony tenodesis. J Orthop Sci. 2013;18:699–704. doi: 10.1007/s00776-013-0429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo I.K., Burkhart S.S. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis using a bioabsorbable interference screw. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lutton D.M., Gruson K.I., Harrison A.K., Gladstone J.N., Flatow E.L. Where to tenodese the biceps: proximal or distal? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1050–1055. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1691-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacKechnie M.A., Chahal J.2, Wasserstein D., Theodoropoulos J.S., Henry P., Dwyer T. Repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears in patients aged younger than 55 years. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:1366–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzocca A.D., Bicos J., Santangelo S., Romeo A.A., Arciero R.A. The biomechanical evaluation of four fixation techniques for proximal biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1296–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzocca A.D., Cote M.P., Arciero C.L., Romeo A.A., Arciero R.A. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1922–1929. doi: 10.1177/0363546508318192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meraner D., Sternberg C., Vega J., Hahne J., Kleine M., Leuzinger J. Arthroscopic tenodesis versus tenotomy of the long head of biceps tendon in simultaneous rotator cuff repair. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136:101–106. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Millett P.J., Sanders B., Gobezie R., Braun S., Warner J.J. Interference screw vs. suture anchor fixation for open subpectoral biceps tenodesis: does it matter? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naudi O.S., Lerue O., Cassagnaud X., Elise S., Leroy X., Maynou C. Étude comparée arthroscopique et histologique du chef long du bíceps brachii: à propôs de 52 cas. Rev Chir Orthop. 2007;93:S32–S37. doi: 10.1016/S0035-1040(07)79303-0. [Arthroscopic and histologic comparative study of the long head of the biceps: 52 casos] [in French] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nho S.J., Reiff S.N., Verma N.N., Slabaugh M.A., Mazzocca A.D., Romeo A.A. Complications associated with subpectoral biceps tenodesis: low rates of incidence following surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:764–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozalay M., Akpinar S., Karaeminogullari O., Balcik C., Tasci A., Tandogan R.N. Mechanical strength of four different biceps tenodesis techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:992–998. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patzer T., Rundic J.M., Bobrowitsch E., Olender G.D., Hurschler C., Schofer M.D. Biomechanical comparison of arthroscopically performable techniques for suprapectoral biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:1036–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richards D.P., Burkhart S.S. A biomechanical analysis of two biceps tenodesis fixation techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:861–866. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rios D., Martetschläger F., Horan M.P., Millett P. Complications following subpectoral biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Said H.G., Babaqi A.A., Mohamadean A., Khater A.H., Sobhy M.H. Modified subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Int Orthop. 2014;38:1063–1066. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2272-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sampatacos N., Getelman M.H., Henninger H.B. Biomechanical comparison of two techniques for arthroscopic suprapectoral biceps tenodesis: interference screw versus implant-free intraosseous tendon fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1731–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sampatacos N., Gillette B.P., Snyder S.J., Henninger H.B. Biomechanics of a novel technique for suprapectoral intraosseous biceps tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanders B., Lavery K.P., Pennington S., Warner J.J. Clinical success of biceps tenodesis with and without release of the transverse humeral ligament. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarmento M. Long head of biceps: from anatomy to treatment. Acta Reumatol Port. 2015;40:26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheibel M., Schröder R.J., Chen J., Bartsch M. Arthroscopic soft tissue tenodesis versus bony fixation anchor tenodesis of the long head of the biceps tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1046–1052. doi: 10.1177/0363546510390777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sethi P.M., Rajaram A., Beitzel K., Hackett T.R., Chowaniec D.M., Mazzocca A.D. Biomechanical performance of subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a comparison of interference screw fixation, cortical button fixation, and interference screw diameter. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shank J.R., Singleton S.B., Braun S., Kissenberth M.J., Ramappa A., Ellis H. A comparison of forearm supination and elbow flexion strength in patients with long head of the biceps tenotomy or tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen J., Gao Q.F., Zhang Y., He Y.H. Arthroscopic tenodesis through positioning portals to treat proximal lesions of the biceps tendon. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;70:1499–1506. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0071-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shon M.S., Koh K.H., Lim T.K., Lee S.W., Park Y.E., Yoo J.C. Arthroscopic suture anchor tenodesis: loop-suture technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2:e105–e110. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song H.S., Williams G.R., Jr. All-arthroscopic biceps tenodesis by knotless winding suture. Arthrosc Tech. 2012;1:e43–e46. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szabó I., Boileau P., Walch G. The proximal biceps as a pain generator and results of tenotomy. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2008;16:180–186. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181824f1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tashjian R.Z., Henninger H.B. Biomechanical evaluation of subpectoral biceps tenodesis: dual suture anchor versus interference screw fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:1408–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The B., Brutty M., Wang A., Campbell P.T., Halliday M.J., Ackland T.R. Long-term functional results and isokinetic strength evaluation after arthroscopic tenotomy of the long head of biceps tendon. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2014;8:76–80. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.140114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valenti P., Benedetto I., Maqdes A., Lima S., Moraiti C. “Relaxed” biceps proximal tenodesis: an arthroscopic technique with decreased residual tendon tension. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3:e639–e641. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vellios E.E., Nazemi A.K., Yeranosian M.G., Cohen J.R., Wang J.C., McAllister D.R. Demographic trends in arthroscopic and open biceps tenodesis across the United States. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:e279–e285. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walch G., Nové-Josserand L., Boileau P., Lévigne C. Subluxations and dislocations of the tendon of the long head of the biceps. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:100–108. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(98)90218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waterman B.R., Arroyo W., Heida K., Burks R., Pallis M. SLAP repairs with combined procedures have lower failure rate than isolated repairs in a military population: surgical outcomes with minimum 2-year follow-up. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3 doi: 10.1177/2325967115599154. 2325967115599154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Werner B.C., Brockmeier S.F., Gwathmey F.W. Trends in long head biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:570–578. doi: 10.1177/0363546514560155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Werner B.C., Evans C.L., Holzgrefe R.E., Tuman J.M., Hart J.M., Carson E.W. Arthroscopic suprapectoral and open subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a comparison of minimum 2-year clinical outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2583–2590. doi: 10.1177/0363546514547226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Werner B.C., Lyons M.L., Evans C.L., Griffin J.W., Hart J.M., Miller M.D. Arthroscopic suprapectoral and open subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a comparison of restoration of length-tension and mechanical strength between techniques. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wittstein J.R., Queen R., Abbey A., Toth A., Moorman C.T., 3rd Isokinetic strength, endurance, and subjective outcomes after biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: a postoperative study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:857–865. doi: 10.1177/0363546510387512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolf R.S., Zheng N., Weichel D. Long head biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: a cadaveric biomechanical analysis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:182–185. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu P.T., Jou I.M., Yang C.C., Lin C.J., Yang C.Y., Su F.C. The severity of the long head biceps tendinopathy in patients with chronic rotator cuff tears: macroscopic versus microscopic results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1099–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yi Y., Lee J.M., Kwon S.H., Kim J.W. Arthroscopic proximal versus open subpectoral biceps tenodesis with arthroscopic repair of small- or medium-sized rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:3772–3778. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Q., Zhou J., Ge H., Cheng B. Tenotomy or tenodesis for long head biceps lesions in shoulders with reparable rotator cuff tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:464–469. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2587-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]