Abstract

Patients with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) typically receive chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy. Although this treatment improves prognosis for most patients, some patients continue to experience recurrence within 5 years. Preclinical studies have shown that immune cell infiltration at the irradiated site may play a significant role in tumor cell recruitment; however, little is known about the mechanisms that govern this process. This lack of knowledge highlights the need to evaluate radiation-induced cell infiltration with models that have controllable variables and maintain biological integrity. Mammary organoids are multicellular three-dimensional (3D) in vitro models, and they have been used to examine many aspects of mammary development and tumorigenesis. Organoids are also emerging as a powerful tool to investigate normal tissue radiation damage. In this review, we evaluate recent advances in mammary organoid technology, consider the advantages of using organoids to study radiation response, and discuss future directions for the applications of this technique.

Keywords: Cell–cell interactions, triple negative breast cancer, ionizing radiation, radiotherapy, immune cell co-culture, organoid models, recurrence

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed form of cancer and the second most lethal in American women.116 Unchecked tumor cell growth occurs as a result of dysfunctional regulation of proliferation within terminal mammary ducts. Histologically, most breast cancers emerge as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), where cancer cells are still contained within the basement membrane surrounding the lobular units. Once cancer cells have escaped the basement membrane, the disease progresses to invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), where cells can metastasize to other organs through the vasculature or lymphatic system.141 Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease, but it is phenotypically classified by the presence of three receptors: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). For patients with cancer overexpressing one or more of these receptors, treatments have been developed to target the overexpressed markers. However, for patients with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), hormone treatments and monoclonal antibodies are unsuccessful, reducing treatment options to chemotherapy, surgery, and radiotherapy.

Despite receiving aggressive treatment, TNBC patients encounter high (13–26%) rates of recurrence.2,3,79 An emerging body of literature suggests that normal tissue damage caused by ionizing radiation may contribute to cancer recurrence through the recruitment of circulating tumor cells (CTCs), and recurrence risks are higher for lymphopenic patients.65,103,115 However, many steps in the tumor reseeding process are unknown. Current in vitro models available for determining the effects of normal tissue damage are limited in their efficacy. Therefore, there is an overwhelming need to engineer robust in vitro models to study radiation-induced normal tissue damage and its relation to tumor cell recruitment and recurrence in TNBC.

One such model that is gaining traction is an organoid model of the mammary gland. Organoids are 3D multicellular constructs that retain relevant architecture and have heterogeneous cell populations, making them an attractive alternative to monolayer cultures that do not recapitulate complex in vivo characteristics. In this review, we will outline recent advances in mammary organoid development, and we will examine the advantages of using mammary organoids as models to evaluate normal tissue damage and radiation-induced cell recruitment.

Radiation Therapy, Cancer Progression, and Recurrence

The relationship between ionizing radiation and cancer progression is complex. Approximately 2/3 of all TNBC patients receive ionizing radiation treatment.2 Overall, outcomes have been positive as patients receiving radiation therapy have a significantly lower likelihood of locoregional recurrence,2 with over 80% living recurrence free after treatment for at least 3 years.38,79

In addition to decreasing recurrence at the primary site, radiation has been observed to hinder tumor growth at distant sites, termed the abscopal effect. In mouse models of Lewis lung carcinoma and fibrosarcoma, it was shown that p53 upregulated the abscopal effect by decreasing tumor growth after irradiation of normal tissue at a distant site.26 The presence of T cells appears to be an important mediator of the abscopal effect. Demari et al. showed that in mouse models with contralateral 67NR TNBC mammary carcinoma tumors, irradiation of one tumor significantly decreased growth of the other in wild type but not in immunocompromised nude mice.36 Furthermore, tumor oxygenation enhances the abscopal effect, and there have been efforts to take advantage of this therapeutically. More recently, Meng and colleagues developed a nanoplatform for inhibiting HIF-1α in 4T1 mouse breast tumors, which synergistically inhibited tumor growth at primary and distant sites when combined with radiation.84

At the same time, an emerging body of literature suggests that ionizing radiation may contribute to recurrence. In 1991, C.F. von Essen described agents like hypoxic cell radiosensitizers, chemotherapy, and surgery that, when combined with radiotherapy, increased metastasis following local tumor irradiation and increased metastatic foci in previously irradiated normal tissues.134 Particular hallmarks associated with tumorigenesis that are upregulated after radiation have not been fully elucidated and are still areas of active research.54 For example, angiogenesis may be influenced by radiation. In zebrafish and mouse models, low dose irradiation of 0.8 Gy was shown to promote angiogenesis and 4T1 tumor progression via upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2).121 Additionally, interactions between irradiated stroma and tumor cells have increased pancreatic tumor invasiveness after doses as low as 5 Gy were applied.98

Lymphocyte count has also been implicated in outcomes for patients, both at the primary site and peripherally. High levels of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes are associated with a more positive prognosis.77 Similarly, peripheral absolute lymphocyte count has been found to predict overall survival in TNBC patients.4 Additional studies revealed that TNBC patients with lymphopenia or low absolute lymphocyte count were also more likely to experience recurrence after radiotherapy.103,115 A lymphopenic pre-clinical model was then used to show that tumor cells from contralateral sites were recruited 10 days after normal tissue irradiation, and macrophage infiltration was necessary for tumor cell recruitment.103

Insights into recurrence can be gained from examining what is known about the metastatic cascade, which is a multistep process. Before the primary site is surgically removed, metastasis is initiated when tumor cells escape by invading into the surrounding stroma and intravasating into the blood stream or lymphatic system.7 Tumor cells can survive in the circulation and travel to distant organs. They may extravasate from the bloodstream and either enter a period of dormancy, remaining undetectable, or can rapidly proliferate, eventually forming a clinically detectable metastasis.7 The most common regions of metastasis of TNBC cells are the lungs, bone, liver, brain, and adrenal glands.8,18,43,138 The local recurrence process is believed to either be caused by tumor cells that have evaded therapy or to follow mechanisms similar to metastasis (Fig. 1). However, rather than colonizing a new site, CTCs may re-colonize the primary site,65 which is commonly defined as the first site of relapse occurring in either the chest wall, the intact breast, ipsilateral axilla, internal mammary nodes, or supraclavicular fossa.146

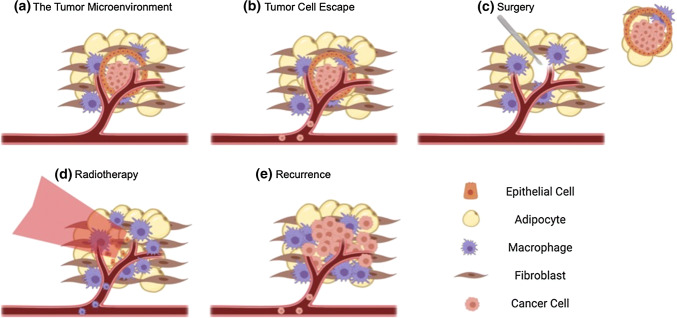

Figure 1.

Cancer recurrence following therapy. (a) Most breast cancers begin within the ducts as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). (b) Cancer cells may escape the primary site and enter the circulation, becoming circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and potentially taking root in distant tissues. (c) Following chemotherapy, the tumor and surrounding stroma is resected surgically. (d) The area is then treated with ionizing radiation, which causes macrophage recruitment to the site of damage. The extent of this recruitment is influenced by immune status. (e) CTCs may facilitate cancer recurrence in addition to tumor cells remaining in the treated site, and this outcome is prevalent in immunocompromised patients.103 Organoids can help elucidate mechanisms of this process, including tumorigenesis,45,149 escape and stromal invasion,42,58 and immune and tumor cell recruitment.51

These findings convey a complicated relationship between radiotherapy, cancer ablation, and cancer progression. To aid in delving deeper into the mechanisms of recurrence, robust in vitro models must be further established to characterize radiation damage to normal tissue and to evaluate how radiation influences tumor and immune cell migration. While in vivo studies remain the standard for pre-clinical trials of radioprotectors, radiosensitizers, and cancer therapeutic screening, 3D in vitro studies serve as an essential complement and can overcome limitations of in vivo mouse models, such as differences in biology, lack of control over complex biological systems, and discrepancies between therapy regimens in mice and humans. Already, murine mammary organoids, which are mammary gland derived primary cells grown in 3D, are being used to model macrophage and tumor cell recruitment after normal tissue irradiation.51 This work can be further expanded to determine the role of normal tissue damage in recurrence.

Radiation-Induced Damage in the Mammary Gland

Ionizing radiation damages cellular DNA. In the mammary gland, the response to radiation is multifaceted due to the diverse tissue composition (Fig. 2). Proliferation rate is correlated to the extent of response to radiation damage.106 Highly proliferative cells, like epithelial cells in the ducts or lobes, rapidly undergo apoptosis and delayed secondary apoptosis associated with mitotic catastrophe.34 Cells that proliferate more slowly, like adipocytes, may enter a state of senescence rather than apoptosis, and their response to radiation damage occurs more slowly, sometimes taking months or years.106 Cell cycle phase, oxygenation status, and interactions with other cell types all influence radiation response. There has therefore been a shift from examining response of homogeneous cell populations to analyzing damage when multiple cell types are present.142 Because of the different cell populations in the mammary gland, there is great interest in understanding the interactions between epithelial, adipose, stromal, and endothelial cells in response to radiation.

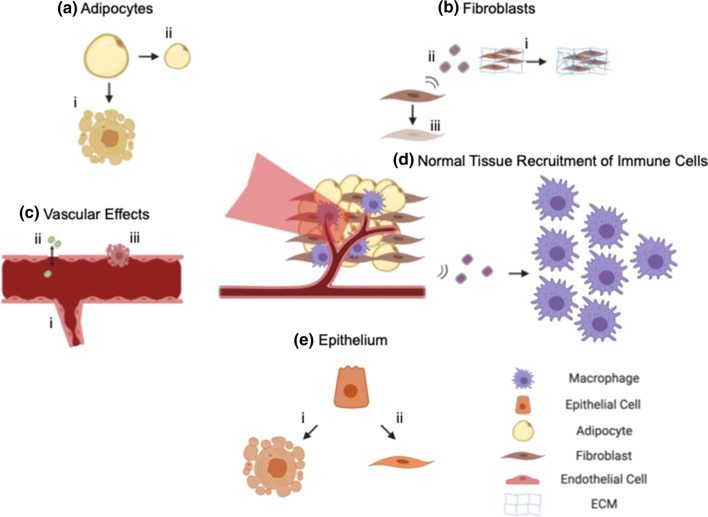

Figure 2.

Characteristics of radiation damage in the mammary gland. (a) After radiation, adipocytes (i) undergo apoptosis, and (ii) decrease in size.101 (b) Fibroblasts (i) increase production of ECM components and cause fibrosis,105 (ii) secrete a variety of cytokines in the pro- and anti-inflammatory response, and (iii) can be induced into a state of senescence.127 (c) Radiation can have a variety of effects on the endothelium and vasculature, including (i) angiogenesis,121 (ii) a temporary increase in endothelial layer permeability,14 (iii) apoptosis of endothelial cells,105 and CD11b+ cell induced vasculogenesis.5 (d) Secreted factors from the irradiated stroma recruit macrophages103 and CD11b+ monocytes.5 (e) Radiation induces apoptosis (i) in epithelial cells or (ii) induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition.9 For each cell type, adipose and fibroblast spheroids,67,68,143 microvascular networks,136 and epithelial organoids40,51,95 can be used as models to isolate individual contributions of the radiation response.

Most breast cancers arise from epithelial cells. Radiation therapy can be used to target tumor cells or can be applied to the area surrounding the resected tumor post-surgery. Morphologically, mammary epithelial tissue exposed to ionizing radiation most commonly undergoes moderate atrophy.41 Within the stromal compartment, fibrosis, or excess deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM), is readily apparent. Treatment over time also has an effect on tolerance of radiation damage, which decreases with each subsequent dose.24 Inflammation of blood vessels is observed as a late effect of radiation within mammary tissue.41 In the vasculature, small capillaries are the most sensitive to ionizing radiation as they are composed of a single layer of endothelial cells.132 Ionizing radiation can disrupt the adhesion of endothelial cells, an observation marked by disruption of VCAM 1 expression in 2D and 3D endothelial cultures.60

The sheer number of proteins secreted by adipocytes (> 400) indicates their important role in cell communication and cross-talk.148 Therefore, changes in secreted cues after irradiation are of particular interest. Crosstalk between adipocytes and tumor cells have been shown to increase tumor cell resistance to therapy. Bochet et al. co-cultured murine 3T3F442A cells that were differentiated into adipocytes with SUM159PT mammary carcinoma cells. At doses of 5 Gy, tumor cells in co-culture displayed higher survival fraction and lower mitotic catastrophe than tumor cells cultured alone.20 Adipocytes have been shown to be sensitive to radiation in vivo. In inguinal fat pads, adipocytes exposed to 7 Gy irradiation were reduced in size and number.101 In addition to causing direct toxicity to cells by double strand DNA breaks, application of ionizing radiation can cause indirect effects through the generation of short-lived reactive oxygen species. In the mammary gland, where there is a large percentage of cells with fat, this can lead to excessive amounts of peroxidation of unsaturated lipids. Lipid peroxidation has been quantitated by malondialdehyde concentration128 and has been correlated with tumor progression.104,119,139

Crosstalk between mammary stroma and parenchyma can play a role in response to radiation, and changes in the stromal compartment can contribute to cancer progression and recurrence. Nguyen and colleagues showed this by adapting a previously developed mammary chimera model.16,93 In this model, the epithelium in the inguinal mammary gland was removed, mice were exposed to whole body low dose irradiation, and fragments of mammary epithelium lacking the tumor suppressor gene p53 were transplanted into the cleared mammary gland. Rather than being used to treat cancer, ionizing radiation was used to initiate tumor growth and progression, and it was found that radiation induced aggressive, ER-tumor growth. This is evidence that radiation-induced changes in the stromal compartment can affect outcomes in the epithelium. One of the major limitations of the chimeric model was that tumor detection in mice required almost a full year. In vitro organoid models could replicate these interactions in a much shorter time frame.

Outcomes for living cells can also be altered by dead cells. A phenomenon called accelerated repopulation has been known for decades.123 In this process, the few cancer cells that may survive radiotherapy proliferate at a markedly increased pace to re-establish the tumor. Radiation-induced death of multiple cell types has been shown to contribute to repopulation, including cancer cells and fibroblasts,55 and this may be mediated by Caspase-3 signaling. However, more complex co-culture models for further probing this process have not been developed.

In addition, the response to radiation therapy can be significantly impacted by the endothelium. Ahn and Brown have shown that after radiation of tumor and normal tissue, recruited CD11b+ bone marrow derived cells (BMDCs) can drive tumor regrowth by upregulating vasculogenesis.5 This recurrence can be prevented by blocking infiltration of BMDCs and preventing vasculogenesis, which has been shown in a glioblastoma model.66 In this study, the authors found that inhibiting the HIF pathway was effective at reducing tumor recurrence after radiotherapy, but this inhibition did not have an impact on recurrence in the absence of radiotherapy. Taken together, these studies highlight the importance of modeling radiation response with in vitro systems that incorporate multiple cell types.

Mammary and Tumor Organoids

Mammary organoids, which are 3D multicellular constructs that retain aspects of the organ’s architecture, upregulate signaling pathways that are lost in 2D culture137 and have heterogeneous cell populations, making them representative models of the mammary gland. They can be generated from a variety of sources (Fig. 3, Table 1), including patient derived reduction mammoplasties,71,75 cell lines,90 mouse mammary epithelial ducts,51,57,95 co-cultures of luminal and myoepithelial cells,118 or single mammary stem cells.61 Mammary organoids are cultured in various vessels or configurations, most often in matrices designed to mimic the basement membrane surrounding ductal lumina.75,94,95 Other culture conditions incorporate microfluidic systems to simulate shear stress and oxygen and nutrient diffusion11 or low adhesion culture conditions, which force cells to self-adhere rather than adhere to tissue culture treated plastic and causes a loss of dimensionality.51 There have been many exciting recent developments in the use of mammary organoids to study biological processes (Table 2), which are described below.

Figure 3.

Organoid culture conditions and applications. *Adapted from Jamieson et al.61 Mammary organoids are derived from normal, non-tumor tissue or tumors from various mammalian sources. They can also be derived from cell lines. Organoids are distinct from monolayer cultures in that their culture conditions facilitate the adoption of a 3D phenotype. They can be forced to adopt a spheroid form when seeded into low adhesion plates, cultured into lumen that recapitulate localized keratin and cadherin expression, or form complex cultures when mammary stem cell niche factors are included. These studies are useful in supplementing in vivo observations, including determining dynamics of tumor cell escape from the primary site, characterizing kinetics and cell-cell interactions between normal tissues and immune cells, and testing therapeutics on tumor cell growth.

Table 1.

Mammary organoid tunability and applicable in vitro assays.

| Sources of organoid tissue | Culture vessels | Assays | Outputs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mammary Epithelium |

Low adhesion plates Basement membrane |

Immune cell co-culture Invasion assays Live cell imaging |

Cystic spherical organoids |

Hacker51 Nguyen-Ngoc95 |

| Patient derived reduction mammoplasty | Micro-patterned microwells | Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence to analyze lineage diversity | Organized bilayered alveoli and ducts | LaBarge71 |

| Patient derived reduction mammoplasty enriched for regenerative CD10+ CD49fhi/EPCAM− cells | Floating collagen gels | Branching | Structures with terminal ductal-lobular units | Linnemann75 |

| Tumor organoids from MMTV-PyMT mice | Microfluidic device with fluid flow and chemokine gradient | Organoid migration | Tumors that migrate through the device | Hwang58 |

| Single sorted basal (K14+) or luminal (K8/18+) CD24+CD29+ mammary stem cells from confetti reporter mice | Basement membrane extract |

Tissue dynamics Cell fate decisions 3D confocal microscopy |

Complex mammary glands over 300 µm in size | Jamieson61 |

| Murine mammary epithelium isolated into varying ratios of myoepithelium and luminal epithelium | Matrigel or Collagen I |

Live cell imaging Cell invasion and dissemination |

Cystic organoids that can invade into the basement membrane | Sirka118 |

Table 2.

Summary of recent methods of mammary organoids and their applications.

| Novel organoid development | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|

| Irradiated organoids recapitulate pre-clinical observations of increased macrophage recruitment | Co-Culture; Radiation Damage | Hacker51 |

| Communication of ECM and intracellular proteins impacts acinar and tumor formation | Development; Tumorigenesis | Furuta45 |

| BCL11b transcription factor inhibits differentiation of mammary stem cells | Regenerative Medicine; Development | Miller86 |

| Macrophages are recruited to tumors and facilitate tumor cell metastasis | Tumorigenesis; The Metastatic Cascade | Linde74 |

| Patient derived explants of breast tumors allow for rapid evaluation of drug efficacy in hormone-dependent cancers | Drug Screening | Centenera28 |

| Human breast epithelial progenitors can be expanded more rapidly in organoid culture than 2D culture | Regenerative Medicine; Development | Chatterjee29 |

| Transcriptome analysis on MCF10A M1–M4 organoid culture reveals that lncRNA stabilizes mRNA of an oncogene | Tumorigenesis | Jadaliha59 |

| Formin Dia1 is necessary for invasion of epithelium into the basement membrane | Development; Tumorigenesis | Fessenden42 |

| Small molecule inhibitor WRG-28 blocks discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR2), inhibiting tumor cell invasion and migration in a TNBC organoid model | Drug Screening | Grither and Longmore47 |

| MAP3K1 deletion confers resistance to AKT inhibitor in organoid model of MCF10A cells | Drug Screening; Therapeutic Resistance | Avivar-Valderas10 |

| Glucocorticoids contribute to loss of myoepithelium, allowing DCIS to become IDC | Tumorigenesis | Zubeldia-Plazaola149 |

| Cancer cells become more invasive in hypoxic and limited nutrient conditions | Tumorigenesis; Microfluidic Systems | Ayuso11 |

| Long-term culture of patient-specific breast cancer organoids | Drug Testing; Personalized Medicine | Sachs108 |

| Biochemical and biomechanical cues cause K14+ leader cells to initiate migration of tumor cells in primary tumor organoids | Metastatic Cascade; Tumorigenesis; Migration; Microfluidics | Hwang58 |

Regenerative Capacity

Culturing organoids long-term, similar to primary cells, is challenging. Timescales for primary-derived organoid culture are on the order of 2 weeks,114 which limits longer term studies. To lengthen these timescales, there has been interest in identifying stem cells or stem-like cells that are highly proliferative and have high regenerative potential as well as identifying factors that contribute to generation of organ-like structures while maintaining stem cell maintenance and homeostasis.29,86 Much of the work in patient derived mammary organoids has been inspired by developing organotypic models of colorectal cancer due to their ease of accessibility from colonoscopies.110 Fundamental studies identifying stem-like cells within the intestine have been done,32 and factors that contribute to stem cell renewal and tissue differentiation have been characterized.109 However, the process of discovery of factors that allow for long term growth and differentiation of mammary organoids is still underway, and some of the factors that facilitate culture of intestinal epithelial organoids do not necessarily translate to mammary epithelial organoids. In 2016, Jardé and colleagues showed that epidermal growth factor (EGF), a protein that had been used for GI and prostate organoid maintenance, did not contribute to long term mammary organoid growth.62 Instead, they found that culturing in media supplemented with Neuregulin-1, a member of the EGF ligand family, caused faster growth, more relevant architecture, and self-organization into basal and luminal compartments. The authors cultured the organoids for over 2 months. They also showed regenerative capacity by injecting organoids into cleared epithelium, and these results show regeneration of the epithelial ductal tree that was confirmed by an additional study.99

Mammary organoids can also be induced from differentiated cells. Rather than taking the approach of isolating tissue stem cells, Panciera et al. de-differentiated terminally differentiated luminal and basal cells.99 The authors introduced dox-lentiviral vectors and induced cellular YAP/TAZ expression. They generated organoids that could be cultured at least 12 months (> 25 passages) and had very similar cytokeratin fluorescent protein patterns and gene expression to organoids derived from mammary stem cells.

Extracellular Matrix (ECM) and Cell-Matrix Interactions

Since Lasfargues established a method using collagenase to digest and isolate adult mouse mammary epithelium in 1957,73 mammary organoids have been used for studying mechanisms of organogenesis, development, metastasis and cancer cell progression. There have been many influential discoveries elucidating mechanisms of cell-matrix interactions. The ECM has been shown to influence organoid growth, conferring insights into in vivo mammary development. The development of mammary organoids embedded in a basement membrane has been shown to depend on material stiffness, which has ranged from 120 to 200 Pa,6 and in tumor microenvironments can be as high as 3.2 kPa.27 In one recent study, Linnemann et al. produced organoids from single human mammary epithelial cells, and these organoids had morphology similar to terminal ductal-lobular units.75 Organoids were cultured in floating collagen gels, which have reduced stiffness compared to attached hydrogels.6 Organoids produced more alveolar structures when grown in free-floating collagen matrix. They also displayed accurate co-localization of basal and luminal markers and exhibited a higher propensity for myoepithelial contractility.75 Interestingly, atomic force microscopy measurements showed that floating collagen gels exhibited stiffnesses more similar to in vivo conditions than adherent collagen gels.6

Additionally, it was shown that ECM composition regulates mammary morphogenesis. Furuta and colleagues investigated the role of laminin proteins affecting morphogenesis signaling pathways in a patient derived mammary organoid model.45 They discovered that laminin-111 upregulated production of nitric oxide, which inhibited tumorigenesis. Inhibition of nitric oxide resulted in poor acinar formation and organization, and the cells displayed a less defined, more proliferative phenotype. Finally, cancer progression was also slowed when matrix-metalloproteinase laminin degradation was inhibited. This study shed light on mechanisms of communication between the ECM and inter-nuclear proteins in regulating acinar formation and tumor progression.

Furthermore, tumor spheroids and stromal cells have been shown to alter ECM properties, which could in turn influence cell behavior.81 Much remains unknown about how these cell-generated forces affect the microenvironment. In one 3D model, dense fibrotic environments resulted in plastic ECM remodeling.82 In another study, Acerbi et al. performed mechanical analysis of human breast tumor tissues.1 They found that breast cancer progression and aggressiveness are linked with collagen linearization. These effects are further enhanced by inflammation and TGF-ß signaling, which has implications for the role of radiation in tumor progression. In a 3D breast cancer cell model, Han et al. discovered that contractions of MDA-MB-231 cells can alter the mechanics of the surrounding ECM in collagen, fibronectin, and Matrigel model systems.53 These modifications potentially provide a mechanism of mechanical communication between cells. As in vitro models become more realistic and complex, organoids and other 3D models are playing a crucial role in analyzing the biomechanics and biophysical mechanisms of cell-matrix signaling, which has particular relevance in evaluating radiation-induced fibrosis.122

Modeling Metastasis

In addition to evaluating factors that contribute to development and mammary gland homeostasis, organoids have also been used to examine various facets of the metastatic cascade. Transcriptome analysis of MCF-10A organoids revealed that long non-coding RNAs were important in preventing breast cancer progression as they supported stability of tumor suppressor mRNAs.59 Organoids have also been used to identify invasive promoting factors like Dia-1 dependent adhesions and glucocorticoids.42,149

Organoid studies have identified mechanisms that would be difficult to image in vivo and impossible to recreate with simple 2D in vitro cultures. For example, Hwang et al. developed an organoid model from transgenic mice.58 In this model, cytokeratin 14 positive (K14+) basal epithelial cells expressed GFP, and primary breast tumor organoids were obtained from mice and cultured in a microfluidic system. A gradient of stromal cell derived factor 1 (SDF1), a cytokine commonly found in the mammary stroma, was induced, and organoids were imaged over time. It was found that K14+ basal cells initiated collective tumor cell migration towards this factor, implicating them as leaders of collective tumor cell escape from the primary site.

Differences in microenvironmental composition (i.e. stromal vs. basement membrane) may influence cancer cell invasiveness, providing insights into the metastatic cascade. In an organoid model, primary human breast carcinomas were grown in different ECM gels to compare their phenotype. Organoids cultured in collagen I matrix, a stromal mimicking microenvironment, were more protrusive and had a higher percentage of disseminated cells than those cultured in Matrigel, a basement membrane-mimicking microenvironment.94 These data suggest that as cancer cells escape the lumen, contact with a stromal microenvironment induces an enhanced metastatic phenotype.

Drug Screening

Due to their faithful recapitulation of tissue architecture and ease of accessibility, organoids are commonly used for drug screening. While some studies have focused on drug testing for organoids derived from cell lines,10,47 there have been recent developments to improve drug screening of patient derived breast cancer organoids, which have contributed greatly to improvements in personalized medicine.28,108 In 2018, a biobank of breast cancer organoids was established.108 These authors were motivated by the fact that systemic therapies are not specific enough for individual cases of breast cancer; that is, heterogeneous cancer phenotypes can display a variety of responses to therapies. This approach can be used for drug development and analysis of in vitro drug response in a heterogeneous population of breast cancers.

Methods of delivering drugs to organoids have also been refined. Organoids grown in 3D matrix (e.g. Matrigel) are dense and compact, limiting delivery of genetic material. Work by Laperroussaz et al. examined a method for transgene expression in organoids.72 Previous strategies for introducing viral vectors included dissociating organoids into single cells before transfection and then re-embedding in Matrigel. However, this method is essentially a 2D transfection as the spatial architecture and polarity is lost after dissociation. Instead, the authors used a microfluidic device to embed organoids into Matrigel microbeads, introduced lentiviral vectors via electroporation, and demonstrated high efficacy of siRNA induction while retaining organoid viability.

Co-Culture Models with Immune Cells

The vast majority of 3D co-culture models with immune cells have used tumor spheroids as opposed to normal tissue organoids. The most common co-culture model has utilized tumor cells and macrophages.50,74,126,140 Macrophages can be seeded within the tumor spheroid to evaluate infiltrated tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) or around the spheroid within the surrounding matrix as a model of macrophages within the stroma. The use of human-derived monocytes provides the most biologically relevant model; however, many studies use the murine RAW 264.7 cell line or bone marrow-derived macrophages as a macrophage model.

To examine the effect of tumor cells on the TAM phenotype, Tevis et al. developed a co-culture model of RAW 264.7 macrophages and MDA-MB-231 TNBC spheroids.126 They determined that cancer cells upregulated macrophage secretion of IL-10 when macrophages were in close proximity or contact with the cancer spheroids, suggesting an increased immunosuppressive macrophage phenotype. Other co-culture studies have studied the effect that macrophages have on tumor cells. Winslow et al. generated spheroids from human MCF7 cancer cells and co-cultured these spheroids with human-derived CD14+ monocytes to investigate the impact that monocytes have on tumor cell gene expression.140 To evaluate changes in transcription in tumor cells, they dissociated the spheroids, sorted the tumor cells, and collected RNAseq data. They determined that co-culture with monocytes downregulated CYP1A1, which can act as an activator of carcinogens. This model presents a straightforward technique for determining how co-cultures may change oncogene expression.

Tumor spheroid and macrophage co-cultures have also contributed to knowledge of the metastatic process. In a recent study, Linde et al. examined how myeloid cells in the mammary gland contributed to cancer cell dissemination.74 Using HER2+ tumor spheroid organoids cultured from transgenic mice, they found that mammary-derived macrophages co-localized with organoids and that this co-localization was associated with CCL2 signaling. CCL2 signaling was further associated with attracting TAMs and inducing an increased invasive phenotype in HER2+ cancer cells.

Other co-culture studies have included a stromal component within tumor spheroids. Kuen and colleagues developed a 3D spheroid model consisting of both pancreatic cancer cells and fibroblasts.70 They co-cultured human monocytes with the spheroids and found that the co-culture polarized monocytes toward an immunosuppressive, M2-like phenotype. Polarized macrophages also displayed immunosuppressive properties when co-cultured with T cells, reducing proliferation of CD3+ T cells and inhibiting activation of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Kuen’s spheroid co-culture model reflected the aggressive, immunosuppressive nature of the pancreatic cancer microenvironment and could serve as a tool to elucidate further mechanisms of tumor progression.

Tumor organoids have additionally been co-cultured with T cells, a model that is becoming increasingly relevant given the importance of immunotherapy. Dijkstra et al. developed a patient-derived colorectal cancer organoid model.37 By co-culturing autologous T cells with cancer organoids, they applied principals of adoptive transfer in a 3D environment, activating and expanding tumor reactive T cells. In this model, T cells killed tumor organoids that had proficient expression of MHC class I but did not prevent proliferation of MHC I-deficient tumor organoids. This is an exciting application of spheroid-immune co-culture that may lead to the advancement of personalized medicine.

Although most 3D co-cultures with immune cells have occurred in the context of tumor spheroids, some studies have paired normal tissue organoids and immune cells. Normal tissue organoid models co-cultured with immune cells can provide insights into the kinetics of cell infiltration into normal tissue. For example, a novel co-culture system of intestinal epithelial organoids and intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) was developed.97 Using time-lapse imaging, the dynamics of IEL interactions with the organoids were analyzed by tracking αβT and γδT cells over the course of two hours and quantifying parameters like mean speed, track length, and alignment of individual lymphocytes. This study demonstrates a powerful way to characterize cell motility in an in vitro system.

Analysis of cell migration and motility has mainly been used to model organogenesis, development, and mammary morphogenesis. Huebner et al. used 3D culture to study ductal elongation in the mammary gland and tracked individual fluorescent cells in mammary organoids using time-lapse imaging. The authors discovered a model of elongation, distinguishing how receptor tyrosine kinases influence both proliferation and cell migration within the mammary duct.57 While live cell time-lapse imaging has elucidated aspects of mammary development, similar techniques would prove valuable to evaluating individual interactions between immune cells and tissue, providing insight into cell morphology and co-localization kinetics. These studies illustrate the potential for culturing immune cells with organoid models of normal tissue damage.

Other Technical Outputs

The increased dimension offered by organoids also brings with it increased potential in complex quantitative outputs. Techniques commonly used for 2D cell culture (e.g. fluorescence microscopy, transcriptomics) can also be applied to organoids. Size and shape diversity in these models have often been ignored, yet differences in morphology may significantly impact results. In a recent study, Zanonoi et al. used software to assess how morphological parameters affect the response of lung cancer spheroids to various treatments.144 Using 3D reconstructions of brightfield organoid images, they evaluated spheroidization time, or the time for cellular aggregation into spherical constructs. They also determined that homogenously sized spheroids had different viability profiles than non-homogeneously sized spheroids, which have potential implications for studying drug and radiation response.

Spheroid morphology has also been assessed in patient-derived tumor organoids. Borten et al. developed Matlab-based software to examine morphologic parameters like area, solidity, and eccentricity of tissues,21 providing a more accessible way to increase the throughput of organoid data. Interestingly, the investigators also evaluated morphological parameters, like solidity, convex area, and kurtosis, with transcriptomic data obtained from RNA sequencing. Integrating these data may reveal insights into the mechanisms regulating organoid development.

Fluorescent image analysis can provide additional complex information in organoid models. For example, in a biomechanical study of tumor cell invasion into the ECM, Kopanska and colleagues used fluorescent staining of collagen fibers to enable quantitation of fiber orientation and alignment.69 Moreover, fluorescent tracking beads validated displacement velocity maps, allowing for visualization of contractile flow speed and magnitude as a function of time. The results obtained from this tension-based model determined how biomechanical forces in the ECM influence invasion.

Investigating Normal Tissue Radiation Damage and Cell Infiltration

Current 2D in vitro models do not recapitulate tissue complexity and cell heterogeneity to properly assess the effects of radiation damage to normal tissue. Organ specific stem cells are necessary for homeostasis and wound healing in multiple organs.85,130 They are progenitors of differentiated, functional cells, and radiation-induced stem cell damage can severely disrupt homeostasis, especially in regions of high proliferation and turnover. While many 2D assays of radiotherapy damage do not incorporate stem cells into their culture,49,120 the impact of low dose radiation on salivary gland stem cells has recently been studied.92 The survival of stem cell derived organoids exposed to 4x0.25 Gy fractionated radiation was shown to be much lower than cells exposed to 1 Gy in a single dose, suggesting that salivary stem cells may have a low dose hypersensitivity. This deviates from preconceptions about a linear response to increasing radiation doses.

Many cytokines are secreted in response to radiation damage112 and have complex and sometimes contradictory roles. For example, normal tissue damage caused by ionizing radiation is known to result in the steady production of both anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β 15 and pro-inflammatory factor IL-6.133 Depending on stage of progression, each of these cytokines can paradoxically behave as tumor suppressors or oncogenic factors in the tumor microenvironment.19,129 Despite extensive studies of normal tissue damage after radiation, there are no approved therapies for radiation-induced fibrosis. While in vivo studies of radiation damage to normal tissue and tumor cell recruitment have limited control over biological variables, most in vitro models in this area are limited in their efficacy.60 There is therefore much interest in developing biologically realistic models to isolate cell-cell interactions and cell-matrix interactions.51 Normal tissue organoids can be used as essential complements to studies of radiation damage mechanisms and their applications to radiation therapy. Current areas of interest include modifying radiation dosing regimens,22,25,78,88,89,111,117 applying normal tissue radioprotectants or tumor radiosensitizers,17,33,48,63,80,96,113,125,145 and modulating immune cell infiltration with other locally targeted therapies.31,39,56,76,131

3D organoid models for studying radiation damage to normal tissue have been examined. A mammary organoid model from epithelial ducts isolated from murine mammary glands was developed to evaluate the influence of radiation on immune cell recruitment.51 Organoids were irradiated ex vivo and co-cultured with RAW 264.7 macrophages. In this model, macrophages preferentially migrated toward irradiated organoids as was shown in previous pre-clinical studies.103

Furthermore, lack of cell heterogeneity can limit conclusions that can be drawn about normal tissue damage. The gut is a commonly studied organ as indirect exposure to radiation can have devastating effects on nutrient uptake. In a study of radiation-induced damage from immune cells to intestinal tissue, co-cultured Caco-2 cells with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) showed increased permeability of the intestinal barrier induced by activity from PBMCs.91 However, recent studies have suggested that endothelial cells drive intestinal radiation response.44,46,100 For example, an organotypic gut-on-a-chip model was used to show that the vascular endothelium mediates radiation damage.60 This suggests that studies without the endothelial compartment may not accurately replicate radiation response.

The ability to obtain clear images on a single-cell scale enables identification of temporal cell behaviors, which can be quantified via cell migration and motility analysis.12,37,57,97 Mammary epithelial organoids are being developed to visualize the kinetics of radiation-induced TNBC cell and macrophage recruitment (Fig. 4). The accessibility of conditioned media allows for characterization of secreted factors by organoids. Variables related to recurrence can be evaluated as a function of radiation damage, including tumor cell invasiveness and macrophage chemotaxis. Proteins and cytokines that play a role in macrophage-facilitated tumor cell infiltration identified from organoid models can be further validated in vivo. Additional components of the mammary gland should be incorporated in future studies, including adipocytes, fibroblasts, and immune cells such as neutrophils, which have been associated with tumor progression and recurrence.102,115 The tunability of this model is therefore a great strength and allows for increased biological relevance in understanding mechanisms of recurrence.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of cell recruitment following irradiation using mammary epithelial organoids. Irradiated mammary organoids can be co-cultured with fluorescent cells, including tumor cells (green) and macrophages (red) as shown, over time for evaluation of cell recruitment. Scale bar is 50 μm.

Future Directions

Despite undergoing intensive chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy, up to 1 in 4 TNBC patients may experience local recurrence. Since ionizing radiation is known to upregulate hallmarks of cancer, such as angiogenesis and metastatic growth, radiotherapy may be associated with microenvironmental changes that promote recurrence in a small but significant subset of patients. However, many of the mechanisms governing this process are still unknown. Organoid models offer an avenue to elucidate these mechanisms. As mammary organoid cultures become more complex and translatable, the adoption of standardized parameters is needed to ensure that studies can be compared. It is important that reproducibility, scale, and biological relevance are considered.

Even with well-controlled media, scaffold, and seeding conditions, organoids can be heterogeneous in size, shape, and morphology. These parameters must be analyzed robustly and systematically in studies employing organoids as differences in morphology can have significant effects on viability profile, development, and other phenotypes.13,30,144 Despite undertaking similar studies, different labs observe unique results.21 To successfully navigate discrepancies in techniques, researchers will benefit from a baseline set of parameters and analytical techniques to adequately and reproducibly characterize organoid cultures.

Organoid cultures can generate 3D constructs much thicker than a cell monolayer, but organoid size is restricted by basic transport phenomena: too large, and the center will develop a hypoxic core as oxygen is consumed faster than it can diffuse to the center. To address this, multiple groups are developing vascular networks within engineered tissues to provide a biologically relevant way to deliver oxygen and nutrients throughout the construct87,135 or creating bioreactors to increase nutrient availability.83,147 An additional hindrance to size is obtaining clear images within large organoids. Indeed, one benefit of organoid models over in vivo studies is the relative ease of imaging. To overcome this challenge, optical clearing protocols have been developed to reduce light scattering and increase the imaging depth in organoids.35,52,64 One recent study reported the development of a high throughput technique for improved fluorescent image resolution at depths of over 100 µm, allowing for increased clarity deep into the organoid.23

Biological relevance, organoid maturation, and architecture are also important design considerations. Although the introduction of a third dimension is more accurate than monolayer cultures, researchers may declare physiological relevance without direct comparison to in vivo architectures. In the case of stem cell-derived organoids, for example, this can be inaccurate as these tissues often resemble fetal rather than adult tissues.107 This could result in a severe limitation in modeling various cancers as they disproportionately affect older populations. Recent studies have begun to make direct comparisons between organoid characteristics and in vivo tissue structure and function.37,99,108

Moving forward, tissue-derived organoids may be used to study additional effects of radiation therapy, including epigenetic changes caused by oxidative stress.124 Organoid models will also benefit from looking beyond a single organ to model diseases with multi-organ pathologies,107 potentially allowing for the characterization of systemic radiation effects. In the near future, organoids will serve an essential role in determining the mechanisms of tumor cell recruitment following therapy. Advances in this field will have significant positive implications for breast cancer patients vulnerable to recurrence.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by NIH Grant #R00CA201304.

Conflict of interest

Benjamin C. Hacker and Marjan Rafat declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Research Involving Human Rights

No human studies were carried out by the authors of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Acerbi I, Cassereau L, Dean I, Shi Q, Au A, Park C, Chen YY, Liphardt J, Hwang ES, Weaver VM. Human breast cancer invasion and aggression correlates with ECM stiffening and immune cell infiltration. Integr. Biol. 2015;7:1120–1134. doi: 10.1039/c5ib00040h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adkins FC, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Lei X, Hernandez-Aya LF, Mittendorf EA, Litton JK, Wagner J, Hunt KK, Woodward WA, Meric-Bernstam F. Triple-negative breast cancer is not a contraindication for breast conservation. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011;18:3164–3173. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1920-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adra J, Lundstedt D, Killander F, Holmberg E, Haghanegi M, Kjellén E, Karlsson P, Alkner S. Distribution of locoregional breast cancer recurrence in relation to postoperative radiation fields and biological subtypes. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2019;105:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afghahi A, Purington N, Han SS, Desai M, Pierson E, Mathur MB, Seto T, Thompson CA, Rigdon J, Telli ML, Badve SS, Curtis CN, West RB, Horst K, Gomez SL, Ford JM, Sledge GW, Kurian AW. Higher absolute lymphocyte counts predict lower mortality from early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24:2851–2858. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahn GO, Brown JM. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 Is required for tumor vasculogenesis but not for angiogenesis: role of bone marrow-derived myelomonocytic cells. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alcaraz J, Xu R, Mori H, Nelson CM, Mroue R, Spencer VA, Brownfield D, Radisky DC, Bustamante C, Bissell MJ. Laminin and biomimetic extracellular elasticity enhance functional differentiation in mammary epithelia. EMBO J. 2008;27:2829–2838. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Mahmood S, Sapiezynski J, Garbuzenko OB, Minko T. Metastatic and triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and treatment options. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2018;8:1483–1507. doi: 10.1007/s13346-018-0551-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambroggi M, Stroppa EM, Mordenti P, Biasini C, Zangrandi A, Michieletti E, Belloni E, Cavanna L. Metastatic breast cancer to the gastrointestinal tract: report of five cases and review of the literature. Int. J. Breast Cancer. 2012;1–8:2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/439023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andarawewa KL, Erickson AC, Chou WS, Costes SV, Gascard P, Mott JD, Bissell MJ, Barcellos-Hoff MH. Ionizing radiation predisposes nonmalignant human mammary epithelial cells to undergo transforming growth factor β-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8662–8670. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avivar-Valderas A, McEwen R, Taheri-Ghahfarokhi A, Carnevalli LS, Hardaker EL, Maresca M, Hudson K, Harrington EA, Cruzalegui F. Functional significance of co-occurring mutations in PIK3CA and MAP3K1 in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2018;9:21444–21458. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayuso JM, Gillette A, Lugo-Cintrón K, Acevedo-Acevedo S, Gomez I, Morgan M, Heaster T, Wisinski KB, Palecek SP, Skala MC, Beebe DJ. Organotypic microfluidic breast cancer model reveals starvation-induced spatial-temporal metabolic adaptations. EBioMedicine. 2018;37:144–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagley JA, Reumann D, Bian S, Lévi-Strauss J, Knoblich JA. Fused cerebral organoids model interactions between brain regions. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:743–751. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakal C, Church G, Perrimon N. Regulating Cell Morphology. Science. 2007;316:1753–1756. doi: 10.1126/science.1140324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker DG, Krochak RJ. The response of the microvascular system to radiation: a review. Cancer Invest. 1989;7:287–294. doi: 10.3109/07357908909039849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barcellos-Hoff M, Derynck R, Tsang M-S, Weatherbee J. Transforming growth factor-b activation in irradiated murine mammary gland. J. Clinc. Invest. 1993;92:2065–2072. doi: 10.1172/JCI117045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Ravani SA. Irradiated mammary gland stroma promotes the expression of tumorigenic potential by unirradiated epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1254–1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barreto-Andrade JC, Efimova EV, Mauceri HJ, Beckett MA, Sutton HG, Darga TE, Vokes EE, Posner MC, Kron SJ, Weichselbaum RR. response of human prostate cancer cells and tumors to combining parp inhibition with ionizing radiation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1185–1193. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertozzi S, Londero AP, Cedolini C, Uzzau A, Seriau L, Bernardi S, Bacchetti S, Pasqual EM, Risaliti A. Prevalence, risk factors, and prognosis of peritoneal metastasis from breast cancer. Springerplus. 2015;4:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1449-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bierie B, Moses HL. Tumour microenvironment—TGFΒ: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:506–520. doi: 10.1038/nrc1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bochet L, Meulle A, Imbert S, Salles B, Valet P, Muller C. Cancer-associated adipocytes promotes breast tumor radioresistance. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;411:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borten MA, Bajikar SS, Sasaki N, Clevers H, Janes KA. Automated brightfield morphometry of 3D organoid populations by OrganoSeg. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18815-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourhis J, Sozzi WJ, Jorge PG, Gaide O, Bailat C, Duclos F, Patin D, Ozsahin M, Bochud F, Germond JF, Moeckli R, Vozenin MC. Treatment of a first patient with FLASH-radiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2019;139:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boutin ME, Voss TC, Titus SA, Cruz-Gutierrez K, Michael S, Ferrer M. A high-throughput imaging and nuclear segmentation analysis protocol for cleared 3D culture models. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29169-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown JM, Probert JC. Long-term recovery of connective tissue after irradiation. Radiology. 1973;108:205–207. doi: 10.1148/108.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown PD, Pugh S, Laack NN, Wefel JS, Khuntia D, Meyers C, Choucair A, Fox S, Suh JH, Roberge D, Kavadi V, Bentzen SM, Mehta MP, Watkins-bruner D. Memantine for the prevention of cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuro. Oncol. 2013;15:1429–1437. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camphausen K, Moses MA, Ménard C, Sproull M, Beecken WD, Folkman J, O’Reilly MS. Radiation abscopal antitumor effect is mediated through p53. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1990–1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casey J, Yue X, Nguyen TD, Acun A, Zellmer VR, Zhang S, Zorlutuna P. 3D hydrogel-based microwell arrays as a tumor microenvironment model to study breast cancer growth. Biomed. Mater. 2017;12:1–12. doi: 10.1088/1748-605X/aa5d5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centenera MM, Hickey TE, Jindal S, Ryan NK, Ravindranathan P, Mohammed H, Robinson JL, Schiewer MJ, Ma S, Kapur P, Sutherland PD, Hoffman CE, Roehrborn CG, Gomella LG, Carroll JS, Birrell SN, Knudsen KE, Ganesh RV, Butler LM, Tilley WD. A patient-derived explant (PDE) model of hormone-dependent cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2018;12:1608–1622. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chatterjee S, Basak P, Buchel E, Murphy LC, Raouf A. A robust cell culture system for large scale feeder cell-free expansion of human breast epithelial progenitors. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018;9:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0994-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Geometric control of cell life and death. Science. 1997;276:1425–1428. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chida S, Okada K, Suzuki N, Komori C, Shimada Y. Infiltration by macrophages and lymphocytes in transplantable mouse sarcoma after irradiation with high-intensity focused ultrasound. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3877–3882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clevers H. The intestinal crypt, a prototype stem cell compartment. Cell. 2013;154:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cline J, Dugan G, Bourland J, Perry D, Stitzel J, Weaver A, Jiang C, Tovmasyan A, Owzar K, Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I, Vujaskovic Z. Post-irradiation treatment with a superoxide dismutase mimic, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, mitigates radiation injury in the lungs of non-human primates after whole-thorax exposure to ionizing radiation. Antioxidants. 2018;7:1–17. doi: 10.3390/antiox7030040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Ruysscher D, Niedermann G, Burnet NG, Siva S, Lee AWM, Hegi-Johnson F. Radiotherapy toxicity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2019;13:1–20. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dekkers JF, Alieva M, Wellens LM, Ariese HCR, Jamieson PR, Vonk AM, Amatngalim GD, Hu H, Oost KC, Snippert HJG, Beekman JM, Wehrens EJ, Visvader JE, Clevers H, Rios AC. High-resolution 3D imaging of fixed and cleared organoids. Nat. Protoc. 2019;14:1756–1771. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demaria S, Ng B, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Kawashima N, Liebes L, Formenti SC. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004;58:862–870. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dijkstra KK, Cattaneo CM, Weeber F, Chalabi M, van de Haar J, Fanchi LF, Slagter M, van der Velden DL, Kaing S, Kelderman S, van Rooij N, van Leerdam ME, Depla A, Smit EF, Hartemink KJ, de Groot R, Wolkers MC, Sachs N, Snaebjornsson P, Monkhorst K, Haanen J, Clevers H, Schumacher TN, Voest EE. Generation of tumor-reactive T cells by co-culture of peripheral blood lymphocytes and tumor organoids. Cell. 2018;174:1586–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dragun AE, Pan J, Rai SN, Kruse B, Jain D. Locoregional recurrence in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: preliminary results of a single institution study. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. Cancer Clin. Trials. 2011;34:231–237. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181dea993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Durante M, Formenti SC. Radiation-induced chromosomal aberrations and immunotherapy: micronuclei, cytosolic DNA, and interferon-production pathway. Front. Oncol. 2018;8:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ewald AJ, Brenot A, Duong M, Chan BS, Werb Z. Collective epithelial migration and cell rearrangements drive mammary branching morphogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:570–581. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fajardo LF. The pathology of ionizing radiation as defined by morphologic patterns. Acta Oncol. 2005;44:13–22. doi: 10.1080/02841860510007440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fessenden TB, Beckham Y, Perez-Neut M, Chourasia AH, Macleod KF, Oakes PW, Gardel ML. Dia1-dependent adhesions are required for invasion by epithelial tissues. J. Cell Biol. 2018;217:1485–1502. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201703145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feys L, Descamps B, Vanhove C, Vral A, Veldeman L, Vermeulen S, De Wagter C, Bracke M, De Wever O. Radiation-induced lung damage promotes breast cancer lung-metastasis through CXCR4 signaling. Oncotarget. 2015;6:26615–26632. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Folkman J, Camphausen K. What does radiotherapy do to endothelial cells? Science. 2001;293:227–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1062892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furuta S, Ren G, Mao JH, Bissell MJ. Laminin signals initiate the reciprocal loop that informs breast-specific gene expression and homeostasis by activating NO, p53 and microRNAs. Elife. 2018;7:1–40. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia-Barros M, Paris F, Cordon-Cardo C, Lyden D, Rafii S, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Fuks Z, Kolesnick R. Tumor response to radiotherapy regulated by endothelial cell apoptosis. Science. 2003;300:1155–1159. doi: 10.1126/science.1082504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grither WR, Longmore GD. Inhibition of tumor–microenvironment interaction and tumor invasion by small-molecule allosteric inhibitor of DDR2 extracellular domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018;115:E7786–E7794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805020115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Groselj B, Ruan J-L, Scott H, Gorrill J, Nicholson J, Kelly J, Anbalagan S, Thompson J, Stratford MRL, Jevons SJ, Hammond EM, Scudamore CL, Kerr M, Kiltie AE. Radiosensitization In vivo by histone deacetylase inhibition with no increase in early normal tissue radiation toxicity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017;17:381–392. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grudzenski S, Raths A, Conrad S, Rübe CE, Löbrich M. Inducible response required for repair of low-dose radiation damage in human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:14205–14210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002213107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guiet R, Van Goethem E, Cougoule C, Balor S, Valette A, Al Saati T, Lowell CA, Le Cabec V, Maridonneau-Parini I. The process of macrophage migration promotes matrix metalloproteinase-independent invasion by tumor cells. J. Immunol. 2011;187:3806–3814. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hacker BC, Gomez JD, SilveraBatista CA, Rafat M. Growth and characterization of irradiated organoids from mammary glands. J. Vis. Exp. 2019;147:e59293. doi: 10.3791/59293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hama H, Hioki H, Namiki K, Hoshida T, Kurokawa H, Ishidate F, Kaneko T, Akagi T, Saito T, Saido T, Miyawaki A. ScaleS: an optical clearing palette for biological imaging. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:1518–1529. doi: 10.1038/nn.4107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Han YL, Ronceray P, Xu G, Malandrino A, Kamm RD, Lenz M, Broedersz CP, Guo M. Cell contraction induces long-ranged stress stiffening in the extracellular matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018;115:4075–4080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1722619115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang Q, Li F, Liu X, Li W, Shi W, Liu FF, O’Sullivan B, He Z, Peng Y, Tan AC, Zhou L, Shen J, Han G, Wang XJ, Thorburn J, Thorburn A, Jimeno A, Raben D, Bedford JS, Li CY. Caspase 3-mediated stimulation of tumor cell repopulation during cancer radiotherapy. Nat. Med. 2011;17:860–866. doi: 10.1038/nm.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang X, Yuan F, Liang M, Lo HW, Shinohara ML, Robertson C, Zhong P. M-HIFU inhibits tumor growth, suppresses STAT3 activity and enhances tumor specific immunity in a transplant tumor model of prostate cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huebner RJ, Neumann NM, Ewald AJ. Mammary epithelial tubes elongate through MAPK-dependent coordination of cell migration. Development. 2016;143:983–995. doi: 10.1242/dev.127944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hwang PY, Brenot A, King AC, Longmore GD, George SC. Randomly distributed K14+ breast tumor cells polarize to the leading edge and guide collective migration in response to chemical and mechanical environmental cues. Cancer Res. 2019;79:1899–1912. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jadaliha M, Gholamalamdari O, Tang W, Zhang Y, Petracovici A, Hao Q, Tariq A, Kim TG, Holton SE, Singh DK, Li XL, Freier SM, Ambs S, Bhargava R, Lal A, Prasanth SG, Ma J, Prasanth KV. A natural antisense lncRNA controls breast cancer progression by promoting tumor suppressor gene mRNA stability. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jalili-Firoozinezhad S, Prantil-Baun R, Jiang A, Potla R, Mammoto T, Weaver JC, Ferrante TC, Kim HJ, Cabral JMS, Levy O, Ingber DE. Modeling radiation injury-induced cell death and countermeasure drug responses in a human Gut-on-a-Chip. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0304-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jamieson PR, Dekkers JF, Rios AC, Fu NY, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. Derivation of a robust mouse mammary organoid system for studying tissue dynamics. Development. 2016;144:1065–1071. doi: 10.1242/dev.145045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jardé T, Lloyd-Lewis B, Thomas M, Kendrick H, Melchor L, Bougaret L, Watson PD, Ewan K, Smalley MJ, Dale TC. Wnt and Neuregulin1/ErbB signalling extends 3D culture of hormone responsive mammary organoids. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:1–14. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang Y, Verbiest T, Devery AM, Bokobza SM, Weber AM, Leszczynska KB, Hammond EM, Ryan AJ. Hypoxia potentiates the radiation-sensitizing effect of olaparib in human non-small cell lung cancer xenografts by contextual synthetic lethality. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016;95:772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ke MT, Fujimoto S, Imai T. SeeDB: A simple and morphology-preserving optical clearing agent for neuronal circuit reconstruction. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:1154–1161. doi: 10.1038/nn.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim MY, Oskarsson T, Acharyya S, Nguyen DX, Zhang XHF, Norton L, Massagué J. Tumor self-seeding by circulating cancer cells. Cell. 2009;139:1315–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kioi M, Brown JM, Vogel H, Schultz G, Hoffman RM, Harsh GR. Inhibition of vasculogenesis, but not angiogenesis, prevents the recurrence of glioblastoma after irradiation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:694–705. doi: 10.1172/JCI40283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klingelhutz AJ, Gourronc FA, Chaly A, Wadkins DA, Burand AJ, Markan KR, Idiga SO, Wu M, Potthoff MJ, Ankrum JA. Scaffold-free generation of uniform adipose spheroids for metabolism research and drug discovery. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-19024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koledova Z. 3D coculture of mammary organoids with fibrospheres: a model for studying epithelial–stromal interactions during mammary branching morphogenesis. In: Koledova Z, editor. Methods in Molecular Biology. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kopanska KS, Alcheikh Y, Staneva R, Vignjevic D, Betz T. Tensile forces originating from cancer spheroids facilitate tumor invasion. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuen J, Darowski D, Kluge T, Majety M. Pancreatic cancer cell/fibroblast co-culture induces M2 like macrophages that influence therapeutic response in a 3D model. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.LaBarge MA, Garbe JC, Stampfer MR. Processing of human reduction mammoplasty and mastectomy tissues for cell culture. J. Vis. Exp. 2013;71:e50011. doi: 10.3791/50011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Laperrousaz B, Porte S, Gerbaud S, Härmä V, Kermarrec F, Hourtane V, Bottausci F, Gidrol X, Picollet-D’Hahan N. Direct transfection of clonal organoids in Matrigel microbeads: a promising approach toward organoid-based genetic screens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lasfargues E. Cultivation and behavior in vitro of the normal mammary epithelium of the adult mouse. Anat. Rec. 1957;127:117–129. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091270111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Linde N, Casanova-Acebes M, Sosa MS, Mortha A, Rahman A, Farias E, Harper K, Tardio E, ReyesTorres I, Jones J, Condeelis J, Merad M, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Macrophages orchestrate breast cancer early dissemination and metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02481-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Linnemann JR, Miura H, Meixner LK, Irmler M, Kloos UJ, Hirschi B, Bartsch HS, Sass S, Beckers J, Theis FJ, Gabka C, Sotlar K, Scheel CH. Quantification of regenerative potential in primary human mammary epithelial cells. Development. 2015;142:3239–3251. doi: 10.1242/dev.123554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu HL, Hsieh HY, Lu LA, Kang CW, Wu MF, Lin CY. Low-pressure pulsed focused ultrasound with microbubbles promotes an anticancer immunological response. J. Transl. Med. 2012;10:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Loi S, Michiels S, Salgado R, Sirtaine N, Jose V, Fumagalli D, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Bono P, Kataja V, Desmedt C, Piccart MJ, Loibl S, Denkert C, Smyth MJ, Joensuu H, Sotiriou C. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes are prognostic in triple negative breast cancer and predictive for trastuzumab benefit in early breast cancer: results from the FinHER trial. Ann. Oncol. 2014;25:1544–1550. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.López Alfonso JC, Parsai S, Joshi N, Godley A, Shah C, Koyfman SA, Caudell JJ, Fuller CD, Enderling H, Scott JG. Temporally feathered intensity-modulated radiation therapy: a planning technique to reduce normal tissue toxicity. Med. Phys. 2018;45:3466–3474. doi: 10.1002/mp.12988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lowery A, Kell M, Glynn R, Kerin M, Sweeney K. Locoregional recurrence after breast cancer surgery : a systematic review by receptor phenotype. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012;133:831–841. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1891-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu L, Jiang M, Zhu C, He J, Fan S. Amelioration of whole abdominal irradiation-induced intestinal injury in mice with 3,3′-Diindolylmethane (DIM) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019;130:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.10.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Malandrino A, Mak M, Kamm RD, Moeendarbary E. Complex mechanics of the heterogeneous extracellular matrix in cancer. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2018;21:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.eml.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Malandrino A, Trepat X, Kamm RD, Mak M. Dynamic filopodial forces induce accumulation, damage, and plastic remodeling of 3D extracellular matrices. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019;15:1–26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Martin I, Wendt D, Heberer M. The role of bioreactors in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meng L, Cheng Y, Tong X, Gan S, Ding Y, Zhang Y, Wang C, Xu L, Zhu Y, Wu J, Hu Y, Yuan A. Tumor oxygenation and hypoxia inducible factor-1 functional inhibition via a reactive oxygen species responsive nanoplatform for enhancing radiation therapy and abscopal effects. ACS Nano. 2018;12:8308–8322. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b03590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Metcalfe C, Kljavin NM, Ybarra R, De Sauvage FJ. Lgr5+stem cells are indispensable for radiation-induced intestinal regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miller DH, Jin DX, Sokol ES, Cabrera JR, Superville DA, Gorelov RA, Kuperwasser C, Gupta PB. BCL11B drives human mammary stem cell self-renewal in vitro by inhibiting basal differentiation. Stem Cell Rep. 2018;10:1131–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miller JS, Stevens KR, Yang MT, Baker BM, Nguyen DHT, Cohen DM, Toro E, Chen AA, Galie PA, Yu X, Chaturvedi R, Bhatia SN, Chen CS. Rapid casting of patterned vascular networks for perfusable engineered three-dimensional tissues. Nat. Mater. 2012;11:768–774. doi: 10.1038/nmat3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Montay-Gruel P, Bouchet A, Jaccard M, Patin D, Serduc R, Aim W, Petersson K, Petit B, Bailat C, Bourhis J, Bräuer-Krisch E, Vozenin MC. X-rays can trigger the FLASH effect: ultra-high dose-rate synchrotron light source prevents normal brain injury after whole brain irradiation in mice. Radiother. Oncol. 2018;129:582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Montay-Gruel P, Petersson K, Jaccard M, Boivin G, Germond JF, Petit B, Doenlen R, Favaudon V, Bochud F, Bailat C, Bourhis J, Vozenin MC. Irradiation in a flash: Unique sparing of memory in mice after whole brain irradiation with dose rates above 100 Gy/s. Radiother. Oncol. 2017;124:365–369. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Morgan MM, Livingston MK, Warrick JW, Stanek EM, Alarid ET, Beebe DJ, Johnson BP. Mammary fibroblasts reduce apoptosis and speed estrogen-induced hyperplasia in an organotypic MCF7-derived duct model. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25461-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Morini J, Babini G, Barbieri S, Baiocco G, Ottolenghi A. The interplay between radioresistant Caco-2 cells and the immune system increases epithelial layer permeability and alters signaling protein spectrum. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nagle PW, Hosper NA, Barazzuol L, Jellema AL, Baanstra M, Van Goethem MJ, Brandenburg S, Giesen U, Langendijk JA, Van Luijk P, Coppes RP. Lack of DNA damage response at low radiation doses in adult stem cells contributes to organ dysfunction. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24:6583–6593. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nguyen DH, Oketch-Rabah HA, Illa-Bochaca I, Geyer FC, Reis-Filho JS, Mao JH, Ravani SA, Zavadil J, Borowsky AD, Jerry DJ, Dunphy KA, Seo JH, Haslam S, Medina D, Barcellos-Hoff MH. Radiation acts on the microenvironment to affect breast carcinogenesis by distinct mechanisms that decrease cancer latency and affect tumor type. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:640–651. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nguyen-Ngoc K-V, Cheung KJ, Brenot A, Shamir ER, Gray RS, Hines WC, Yaswen P, Werb Z, Ewald AJ. ECM microenvironment regulates collective migration and local dissemination in normal and malignant mammary epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;89:E2595–E2604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212834109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nguyen-Ngoc K-V, Shamir ER, Huebner RJ, Beck JN, Cheung KJ, Ewald AJ. 3D culture assays of murine mammary branching morphogenesis and epithelial invasion. In: Nelson CM, editor. Tissue Morphogenesis: Methods and Protocols. New York: Springer; 2015. pp. 135–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Noël G, Godon C, Fernet M, Giocanti N, Mégnin-Chanet F, Favaudon V. Radiosensitization by the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor 4-amino-1,8-naphthalimide is specific of the S phase of the cell cycle and involves arrest of DNA synthesis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:564–574. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nozaki K, Mochizuki W, Matsumoto Y, Matsumoto T, Fukuda M, Mizutani T, Watanabe M, Nakamura T. Co-culture with intestinal epithelial organoids allows efficient expansion and motility analysis of intraepithelial lymphocytes. J. Gastroenterol. 2016;51:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1170-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ohuchida K, Mizumoto K, Murakami M, Qian LW, Sato N, Nagai E, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Tanaka M. Radiation to stromal fibroblasts increases invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells through tumor-stromal interactions. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3215–3222. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Panciera T, Azzolin L, Fujimura A, Di Biagio D, Frasson C, Bresolin S, Soligo S, Basso G, Bicciato S, Rosato A, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. Induction of expandable tissue-specific stem/progenitor cells through transient expression of YAP/TAZ. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:725–737. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Paris F, Fuks Z, Kang A, Capodieci P, Juan G, Ehlelter D, Halmovitz-Friedman A, Cordon-Cardo C, Kolesnick R. Endothelial apoptosis as the primary lesion initiating intestinal radiation damage in mice. Science. 2001;293:293–297. doi: 10.1126/science.1060191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Poglio S, Galvani S, Bour S, André M, Prunet-Marcassus B, Pénicaud L, Casteilla L, Cousin B. Adipose tissue sensitivity to radiation exposure. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;174:44–53. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Powell DR, Huttenlocher A. Neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rafat M, Aguilera TA, Vilalta M, Bronsart LL, Soto LA, von Eyben R, Golla MA, Ahrari Y, Melemenidis S, Afghahi A, Jenkins MJ, Kurian AW, Horst KC, Giaccia AJ, Graves EE. Macrophages promote circulating tumor cell–mediated local recurrence following radiotherapy in immunosuppressed patients. Cancer Res. 2018;78:4241–4252. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]