Abstract

Background

Several standards have been developed to assess methodological quality of systematic reviews (SR). One widely used tool is the AMSTAR. A recent update - AMSTAR 2 - is a 16 item evaluation tool that enables a detailed assessment of SR that include randomised (RCT) or non-randomised studies (NRS) of healthcare interventions.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of SR on pharmacological or psychological interventions in major depression in adults was conducted. SR published during 2012–2017 were sampled from MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Database of SR. Methodological quality was assessed using AMSTAR 2. Potential predictive factors associated with quality were examined.

Results

In rating overall confidence in the results of 60 SR four reviews were rated “high”, two were “moderate”, one was “low” and 53 were “critically low”. The mean AMSTAR 2 percentage score was 45.3% (standard deviation 22.6%) in a wide range from 7.1% to 93.8%. Predictors of higher quality were: type of review (higher quality in Cochrane Reviews), SR including only randomized trials and higher journal impact factor.

Limitations

AMSTAR 2 is not intended to be used for the generation of a percentage score.

Conclusions

According to AMSTAR 2 the overall methodological quality of SR on the treatment of adult major depression needs improvement. Although there is a high need for summarized information in the field of mental health, this work demonstrates the need to critically assess SR before using their findings. Better adherence to established reporting guidelines for SR is needed.

Keywords: Public health, Epidemiology, Psychiatry, Depression, Evidence-based medicine, AMSTAR 2, Methodological quality, Risk of bias, Systematic review, Major depression

Public health; Epidemiology; Psychiatry; Depression; Evidence-based medicine; AMSTAR 2; Methodological quality; Risk of bias; Systematic review; Major depression.

1. Introduction

Publication of systematic reviews (SR) has increased rapidly over the last 30 years with many of them having serious flaws (Ioannidis, 2016). Whereas SR should provide a comprehensive and objective appraisal of evidence, poor reporting and flaws in methodological quality are frequent (Pussegoda et al., 2017b). Several standards have been developed to assess methodological quality of SR (Pussegoda et al., 2017a; Zeng et al., 2015). One widely used tool is the AMSTAR (a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews, published in 2007) (Shea et al., 2007). The methodological quality of SRs of mental or physical disorders is moderate to disappointing according to AMSTAR (Goldkuhle et al., 2018; Ho et al., 2015; Li et al., 2014; Tao et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016). Several critiques of the AMSTAR instrument have been published. Among the issues raised were the lack of an overall assessment of the quality of SR, problematic response options and the failure to take into account further developed methods for assessing the quality of the body of evidence (Burda et al., 2016; Faggion, 2015; Wegewitz et al., 2016).

A recent update of AMSTAR - AMSTAR 2 (Shea et al., 2017) - is an adaptation that incorporates critiques and developments in the science of SRs. The 16 item evaluation tool enables a more detailed assessment of SR that include randomised (RCT) or non-randomised studies (NRS) of healthcare interventions than its predecessor. It allows a more detailed evaluation of SR and a rating of the overall confidence in the results of the review. The original publication of AMSTAR 2 showed a moderate to substantial inter-rater reliability (IRR) for most items (Shea et al., 2017), which was confirmed by other publications (Lorenz et al., 2019; Pieper et al., 2019) and can be seen as a valid instrument for assessing the methodological quality of SRs.

Major depression is a common mental disorder with high prevalence and mortality. According to a recent WHO report 4.4% of the world's population is estimated to suffer from depression (World Health Organization (WHO), 2017). In light of the high need for reliable and summarized information for clinicians as well as policy makers in the field, it is important to see how the new instrument AMSTAR 2 can be applied to SR that include RCT and/or NRS in mental health and whether AMSTAR 2 helps to identify dependable SR.

The present study assesses the methodological quality of SRs in the treatment of adult major depression using AMSTAR 2 and identifies potential predictive factors associated with quality. In order to reflect current methodological practice and quality, our sample includes SR published between 2012 and 2017.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol

The design and eligibility criteria of this project were based on an a priori written protocol. We followed the protocol and had no deviations during our study. The protocol was prospectively registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and can be accessed at =www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42018110214 (Matthias et al., 2018). Study reporting is provided in reference with the Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (Liberati et al., 2009) and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)statement (von Elm et al., 2008).

2.2. Bibliographic search

Electronic searches in August 2017 in the bibliographic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) took place. We used a combination of MeSH terms and key words to identify SRs published between 2012 and 2017 on the topic “major depression” and did not apply any restrictions on language or region. Considering the short half-life of medical knowledge, a search period of 5 years was chosen (Shojania et al., 2007; Shekelle et al., 2001). Detailed search terms are included in appendix A. We imported all citations into an electronic database (EndNote, X9).

2.3. Data collection

Two authors independently screened the titles, abstracts and full texts of the retrieved literature to assess their eligibility. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

SRs on pharmacological and psychological interventions for major depression in adults were evaluated according to the a priori developed inclusion and exclusion criteria below. Even though our study is according to synthesizing the results a cross-sectional study, these criteria correspond to a real PICO-question that arises, for example, in the preparation of an overview of reviews (Becker and Oxman, 2015) or in guideline development in mental health. The inclusion criteria in brief were:

-

1)

SR of RCT and/or NRS with a systematic search in at least one bibliographic database,

-

2)

adult patients (≥18 years) with acute major depression (diagnosis according to a recognised classification system, e.g. ICD-10 or DSM-IV or a validated questionnaire),

-

3)

pharmacological or psychological intervention,

-

4)

English or German language,

-

5)

publication date between July 2012 and July 2017.

Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are included in appendix B.

2.4. Data extraction (coding)

Two authors independently coded the following information onto a data collection template in Excel (Microsoft Excel 2016, Microsoft):

-

1)

journal name and year of publication (2012–2017),

-

2)

author information (region of the affiliation of the corresponding author [Europe, North American Region, Asia, other regions] and number of authors [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 or >6]),

-

3)

journal impact factor (at year of publication, sources: InCites Journal Citation Reports by Thomson Reuters, website of the journal),

-

4)

open access status (OA, yes or no, sources: InCites Journal Citation Reports by Thomson Reuters, website of the journal),

-

5)

sponsorship of the SR (no sponsorship, industrial sponsorship, no information),

-

6)

topic (intervention) of the SR (pharmacological or psychological),

-

7)

type of review (Cochrane vs. non-Cochrane reviews),

-

8)

inclusion criteria (only RCT or both RCT and NRS)

Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

2.5. Appraisal tool

The methodological quality was evaluated using AMSTAR 2. AMSTAR 2 is a 16-item questionnaire.

Items are evaluated either with “yes” or “no” (items 1, 3, 5, 6, 10, 13, 14, and 16); with “yes”, “partial yes”, or “no” (items 2, 4, 7, 8, and 9); or with “yes”, “no”, or “no meta-analysis conducted” (items 11, 12, and 15). A “yes” answer means that the item is fulfilled and is therefore considered a positive result. Each review was appraised by four independent evaluators. The relevant data were extracted onto a data collection template in Excel (Microsoft Excel 2016, Microsoft). Consensus was reached according to majority principle (Lorenz et al., 2019): in case of an ambiguous result, the judgement of the most experienced rater in each group was taken as final judgement. These cases occurred in 10.4% (106 of 1020) of all ratings (Lorenz et al., 2019). After reaching consensus on each of the 16 items, we applied two approaches to generate an overall assessment.

2.6. Data analysis

First two authors independently performed a rating of overall confidence in the results of the review using the critical domains recommended by Shea et al., (2017). Details about the rating process can be found in Lorenz et al., (2019). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. For the overall confidence rating the response options “high”, “moderate”, “low” and “critically low” were possible. Second we investigated the relationship between the numbers of items fulfilled by each SR according to the appraisal tool in order to achieve a more differentiated picture (Shea et al., 2017 warns against the use of a percentage score). An AMSTAR 2 percentage score was calculated according to Fleming et al., (2014). For each of the 16 items a score of 0 (answer “no”), 1 (answer “yes”) or 0.5 (answer “partial yes”) was given, summed up and converted to a percentage (%) scale. In the case of SR in which no meta-analysis was undertaken, this percentage score includes three non-applicable items. The denominators in such cases were therefore reduced accordingly in order to calculate a score based on the remaining applicable items only.

We performed descriptive data synthesis of our findings according to the individual items of the AMSTAR 2, the overall confidence of the instrument and the AMSTAR 2 percentage score.

A priori planned subgroup analysis of AMSTAR 2 percentage scores were performed to assess possible differences for the type of intervention in the SR (pharmacological or psychological), the type of review (Cochrane vs. non-Cochrane reviews), and open access status (yes vs. no) and t-test was used to test the significance. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine differences due to the type of intervention, while the review type is already known to be a strong predictor (Goldkuhle et al., 2018) and the open access status did not show a significant impact on the quality of the study (Zhu et al., 2016) in an analysis using AMSTAR ratings.

We additionally investigated the influence of all coded variables on the percentage score. These variables compromised year of publication, region of the affiliation of the corresponding author, number of authors, journal impact factor (JIF) at year of publication (no JIF, 0–2, 2–4, 4–6 or >6), open access status, sponsorship, topic of the SR, type of review (Cochrane vs. non-Cochrane reviews), and SR including only RCT (only RCT or both RCT and NRS). Depending on the number of levels of the categorical variables, a t-test was applied for the dichotomous variables (e.g. OA) and a one-way ANOVA for the multiple level variables (e.g. JIF).

As previous literature has shown that valid predictors for the methodological quality of SRs included type of review (higher quality in Cochrane Reviews) (Goldkuhle et al., 2018) and JIF (Fleming et al., 2014), we wanted to test these predictors in the current set of SRs together with six further exploratory predictors: publication year, region, number of authors, OA, sponsorship, inclusion of only RCT. We also included the type of intervention (pharmacological or psychological interventions) in the model, because we manipulated this factor in our experimental design. In order to implement all predictors in one analysis, we performed a hierarchical stepwise regression analysis. To this end, in the first step we defined the predictors type of review (Cochrane vs. non-Cochrane reviews) and JIF, according to previous findings. The second step included only the predictor of the experimental design and the third step all exploratory factors. We only included predictors in the third step if its significance level was p < 0.2. The level of statistical significance for all tests was set at 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 25, IBM Corporation).

3. Results

3.1. Sample size

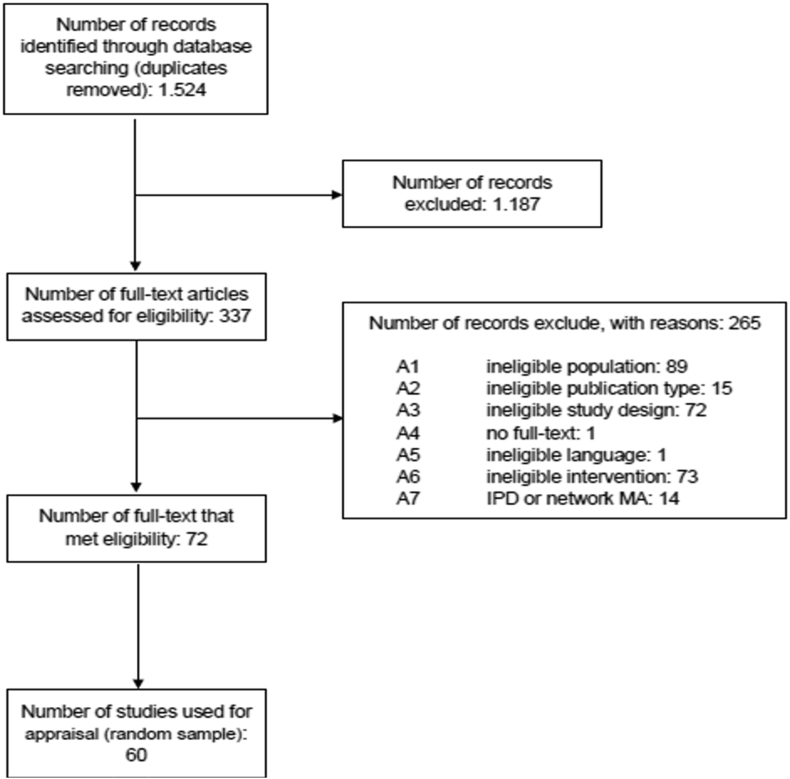

The electronic literature search identified 1.524 citations after the elimination of duplicates. Three hundred and thirty-seven studies were eligible for full text review. Two hundred and sixty-five were excluded according to eligibility criteria. A list of the excluded studies with the reason for exclusion is available on request. Thus, 72 SR comprising 30 SRs with psychological and 42 SRs with pharmacological interventions met our eligibility criteria (Flow chart in Figure 1). Thirty out of 42 pharmacological SRs were randomly selected and served together with the identified 30 psychotherapeutic SRs as sample for this study (list of included studies in appendix C).

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the systematic biliographic search.

3.2. General characteristics

In our sample, 70% (42/60) SR included only RCT, 6.7% (4/60) were Cochrane Reviews and 23.3% (14/60) were open access articles. The corresponding authors' region of affiliation were 53.3% (32/60) Europe, 30% (18/60) North America, in 10% (6/60) Asia and 6.7% (4/60) in other regions. Twenty-two SR had 1 to 3 authors, 25 SR had 4 to 6 and 13 had more than 6. The JIF ranged from no impact factor to 44.4 (mean 4.6 ± 6.9). In 6.7% (4/60) an industry sponsorship of the SR was declared, in 70% (42/60) the authors did not declare a sponsor and in 23.3% (14/60) this information was not available. The distribution of SR according to their publication year was as follows: 8 in 2012, 11 in 2013, 13 in 2014, 12 in 2015, 11 in 2016 and 5 in 2017. Characteristics of all included SR are shown in table A3 in appendix D.

3.3. Methodological quality

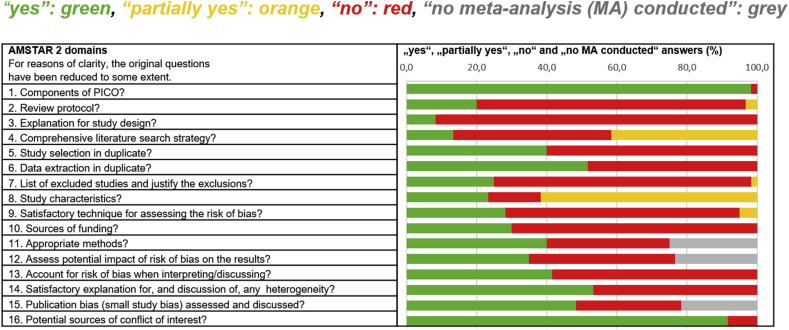

The methodological quality was assessed using AMSTAR 2. The agreement among reviewers was moderate to substantial in most of the items with a median kappa value across all items of moderate agreement (Lorenz et al., 2019). In only four items of AMSTAR 2 (item 1, 6, 14, 16) did the majority (more than 50%) of the SRs score “yes”. There are three items that were only fulfilled by 20% or less of the SRs (item 2, 3 and 4). The results according to all AMSTAR 2 items are shown in Figure 2 and table A5 in appendix F).

Figure 2.

Methodological quality of 60 SR according to the 16 items of AMSTAR 2.

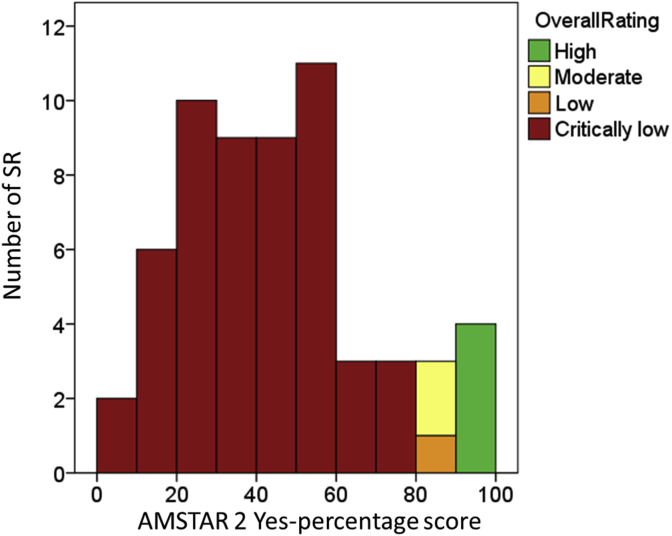

In rating overall confidence in the results of the SR according to Shea et al., (2017) only four reviews were rated “high” (three of them Cochrane Reviews), two were “moderate”, one was “low” and 53 were “critically low”. The mean AMSTAR 2 percentage score was 45.3% (standard deviation 22.6%) in a wide range from 7.1% to 93.8% (appraisals for all SR can be found in table A4 in appendix E). The corresponding AMSTAR 2 percentage scores for the 53 “critically low” reviews ranged in a wide corridor from 7.1% to 75.0%, whereas the AMSTAR 2 percentage score for the “low” review was 84.4%, the two “moderate” reviews had 87.5% each and the “high” reviews were homogeneous in the range from 90.6% to 93.8% (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Histogram with number of SR in the respective AMSTAR 2 percentage scores and color-coded the rating of the overall confidence in the results of the SR.

3.4. Subgroup analysis

Neither the type of intervention (pharmacological or psychological, T = -0.77, p = 0.445) nor open access status (T = -0.42, p = 0.68) involved differences in AMSTAR 2 percentage scores (Table 1). A significant difference was found by comparing Cochrane and non-Cochrane-Reviews (T = -16.42, p < 0.001) that favours Cochrane Reviews, even though our sample only included four Cochrane Reviews (Table 1). Additionally, we did this analysis with the overall confidence rating as dependent variable. The results showed the same pattern as the percentage score: while type of intervention (Z = -1.194, p = 0.332) and open access status (Z = -0.549, p = 0.677) were not significant, a significant difference was found for type of review (Z = -5.797, p < 0.001). For completeness, we have also carried out subgroup analyses based on the exploratory variables (details can be found in appendix G).

Table 1.

Mean AMSTAR 2 Percentage scores with standard deviation (SD), range and interquartile range (IQR) in subgroups (a priori specified variables).

| Mean in % (SD) | Range | IQR | T-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | 45.3 (22.6) | 7.1–93.8 | 27.2–59.0 | ||

| A priori specified variables | |||||

| Type of intervention | -0.77 | 0.445 | |||

| pharmacological | 43.1 (20.2) | 7.1–90.6 | 26.9–57.0 | ||

| psychological | 47.6 (24.6) | 7.1–93.8 | 27.8–62.5 | ||

| Type of Review | -16.42 | <0.001 | |||

| Cochrane | 92.2 (2.7) | 87.5–93.8 | 89.1–93.8 | ||

| other (non-Cochrane) | 42.0 (19.5) | 7.1–90.6 | 26.9–55.5 | ||

| Open Access status | -0.42 | 0.68 | |||

| Yes | 47.6 (17.8) | 26.0–90.6 | 30.5–58.9 | ||

| No | 44.7 (23.9) | 7.1–93.8 | 26.4–59.4 | ||

3.5. Predictors of methodological quality

In order to identify predictors of methodological quality, we conducted a hierarchical regression analysis (Table 2). The first step revealed that both JIF (β = 0.291, p = 0.009) and type of review (β = 0.475, p < 0.001) were significant predictors (R2 = 0.385, p < 0.001). Adding the experimental design type of intervention (step 2, β = 0.039, p = 0.721) did not explain the significantly higher variance (β = 0.039, R2 change = 0.001, F (1,56) = 0.129, p = 0.721). In the third step, only exploratory predictors with a significance level of p < 0.2 were added. This was the case only for the predictor SR including only RCT (only RCT or both RCT and NRS; β = 0.287, p = 0.007). Adding this predictor explained significantly more variance (β = 0.287, R2 change = 0.078, F (1,55) = 7.98, p = 0.007) for the prediction of methodological quality.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression (step 1 - predictors found in literature, step 2 – type of intervention, step 3 - exploratory predictors that had a significance level of p < 0.2).

| Model | B | SE B | β | 95%-CI β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 - R2 = 0.385 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Constant | 30.08 | 5.035 | <.001 | ||

| Cochrane | 43.1 | 9.78 | .475 | [.259; .691] | <.001 |

| JIF | 5.85 | 2.17 | .291 | [.075; .507] | .009 |

| Step 2 - ΔR2 = 0.001 (p = 0.721) | |||||

| Constant | 28.8 | 6.2 | <.001 | ||

| Cochrane | 43.36 | 9.88 | .478 | [.260; .696] | <.001 |

| JIF | 6.03 | 2.24 | .300 | [.077; .523] | .009 |

| Intervention | 1.76 | 4.91 | .039 | [-.179; .257] | .721 |

| Step 3 - ΔR2 = 0.078 (p = 0.007) | |||||

| Constant | 21.45 | 6.4 | .001 | ||

| Cochrane | 39.22 | 9.43 | .432 | [.224; .640] | <.001 |

| JIF | 5.33 | 2.13 | .266 | [.054; .479] | .015 |

| Intervention | .149 | 4,66 | .003 | [-.185; .191] | 0.975 |

| RCT vs. NRS | 14.15 | 5.01 | .287 | [.083; .491] | .007 |

The JIF of Cochrane Reviews of the included publications was around 6 and therefore relatively high. In order to investigate a possible confounding between Cochrane reviews and JIF, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding the four Cochrane reviews and the predictor Cochrane review in the first step. The results of this analysis revealing also JIF (Step 3: β = 0.318, p = 0.015) and RCT vs. NRS (Step 3: β = 0.336, p = 0.009) as significant predictors (Step 1: R2 = 0.117, p = 0.01; Step 2: ΔR2 = 0.004, p = 0.611, Step 3: ΔR2 = 0.11, p = 0.009).

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

The methodological quality of the SR on pharmacological and psychological interventions for major depression in our current and representative sample was disappointing. Specific items including reference to a protocol, an explanation for the study design and the list of excluded studies with justification of the exclusions were found to be particularly poorly addressed (in ≤20% of SR).

In rating overall confidence in the results of the SR only 7 out of 60 SR were not in the lowest category, four of them Cochrane Reviews. The AMSTAR 2 percentage scores with a mean of 45.3% (±22%) show limited quality in many of the included SR.

We found a small positive relationship between methodological quality and higher JIF. Whether a SR was a Cochrane Review and/or included only RCT were particularly influential.

In almost 90% of the sample of SR, overall confidence in the results of the SR were “critically low”. Although SRs with AMSTAR 2 percentage scores of 7.1%–75.0% were present in the category “critically low”, the use of these review's findings should be limited. Although there is a high need for reliable and summarized information for clinicians as well as policy makers in the field of mental health, this work demonstrates the need to critically assess SR before using their findings.

AMSTAR 2 can be a useful tool for appraising SR that include RCT and/or NRS in the mental health field. Depending on the research question, reliance on the proposal for rating overall confidence according to the authors of AMSTAR 2 (Shea et al., 2017) is unlikely to lead to sufficient discrimination. Appraisers could therefore decide a priori about deletion, addition or replacement of the critical items and may even develop a separate scheme for interpreting weaknesses detected in critical and non-critical items. However this approach needs further research. Further work is also needed on operational criteria for some of the items in the scale. For instance item 3, a new item in AMSTAR 2, requires an explanation of study design selection and also for SR including only RCT to be able scored with “yes”. This was one of the items that was very poorly addressed in our sample. Not even the SR with “high” or “moderate “confidence explained their decision to include only RCT, because this is considered to be the gold standard for healthcare interventions. While the demand for an explanation is understandable for SR wishing to include NRS, it is of questionable value for SR with only RCT.

4.2. Our findings in context

Our results of disappointing methodological quality of SRs in the mental health field are in line with assessments of methodological quality of SRs with the previous instrument AMSTAR in SR of depression (Li et al., 2014; Rice et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2016), surgery (Zhang et al., 2016), cancer (Goldkuhle et al., 2018; Tao et al., 2017), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Ho et al., 2015) or in SR of core clinical journals (Fleming et al., 2014). On the other hand, there are only few areas in medicine in which studies showed a good quality of SR. They include health literacy and cancer screening (Sharma and Oremus, 2018) and SRs referenced in clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of opioid use disorder (Ross et al., 2017).

A few studies have used AMSTAR 2 on topics including dentistry (Hasuike et al., 2019), acupuncture (Zhang et al., 2018), Tai Chi in Parkinson's Disease (Kedzior and Kaplan, 2019) and surgery (Yan et al., 2019). They all demonstrated that the majority or all of the included SRs had low methodological quality and in the majority the overall confidence in the results of the SR was considered to be “critically low”. This is in line with our results. However, three of studies using AMSTAR 2 had a low sample count of 5, 10 and 23 SR respectively (Hasuike et al., 2019; Kedzior and Kaplan, 2019; Zhang et al., 2018) and only one study included more than 100 meta-analyses (Yan et al., 2019).

In our study we observe a possible floor effect (53 of 60 reviews were rated as critically low). Leclercq et al. (2020) found something similar and criticized that AMSTAR 2 is lacking discriminating capacity. The assessment of overall confidence by the authors of AMSTAR 2 (Shea et al., 2017) may have to be adjusted in the future. Our finding of the type of review as a strong predictor (higher quality in Cochrane Reviews) is in line with a comparison of cancer-related SRs published in the Cochrane Database of SRs with those published in high-impact medical journals that showed consistently higher methodological quality of Cochrane Reviews (Goldkuhle et al., 2018) as well as a quality assessment of meta-analyses on depression (Zhu et al., 2016). Previous studies have also shown positive associations between JIF and methodological quality of SR, with better quality in higher impact journals (Fleming et al., 2014) and SR including only RCT, with better quality compared to SR also including NRS (Zhu et al., 2016).

For our remaining exploratory predictors (publication year, region, number of authors, OA, sponsorship) we found no influence on the quality of the SR even if the literature occasionally describes positive associations. One example is the region of the first author. While one study showed poorer quality in meta-analyses out of the Chinese Biomedicine Literature Database (which only contains studies published in Chinese) compared to Cochrane Reviews and claims the quality of evidence in so-called “Chinese meta-analyses” needs to be improved (Yao et al., 2016), another study showed no differences in methodological and reporting quality of SRs from China or the USA (Tian et al., 2017).

In two subsets of our sample (each 30 SR) validity results showed a strong positive association for AMSTAR and AMSTAR 2 (r = 0.91) as well as ROBIS and AMSTAR 2 (r = 0.84) according to the aggregated “yes” scores of the different instruments (Lorenz et al., 2019), indicating AMSTAR 2 is closely related to both ROBIS and AMSTAR.

AMSTAR 2 scores might be affected by the completeness of reporting, which is not addressed in this tool but can be analyzed with PRISMA (Liberati et al., 2009). In a recent study the effect of the explicit mention of PRISMA on the completeness of the reporting was investigated (Leclercq et al., 2019). The authors assessed the 27 PRISMA items in 206 meta-analysis (MA) indexed in PsycINFO in 2016 and found perfect adherence to PRISMA in less than 4% of the MA and a positive influence on the reporting completeness of MA by explicit mention of PRISMA. However, they did not report the association between PRISMA ratings and AMSTAR 2 ratings. This issue would clearly benefit from further research.

4.3. Strengths

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the results of AMSTAR 2 appraisal of SR in mental health under conditions that are comparable to the intended application. All SRs were related to a real PICO question and the results can be used for the creation of an overview of SRs for the treatment of major depression or in guideline development.

The current study is furthermore comprised a relatively large sample (60 SRs) and was conducted based on an a priori published protocol, a comprehensive search strategy and all critical steps done at least by two independent persons, thus ensuring the validity and reliability of our findings.

4.4. Limitations

The study has also some limitations. We did a cross-sectional methodological study and analysed – as a priori planned in our protocol - a relatively large sample of 60 SR (30 SR with pharmacological and 30 SR with psychological interventions). We did not intend to depict the full evidence base, but rather to select an adequate sample. We therefore randomly sampled 30 reviews from each category in order to avoid bias. Nevertheless, for reasons of completeness, one of the authors assessed the AMSTAR 2 rating in overall confidence for the remaining 12 SR as described above and found no significant difference compared to the selected 60 SR (details in appendix H).

Our quality assessment was based on AMSTAR 2, an instrument previously validated for the assessment of SRs from RCT and NRS. AMSTAR 2 is not intended to be used for the generation of a percentage score (Shea et al., 2017). The use of summary scores from appraisal tools has been a matter of much discussion in the literature (Burda et al., 2016; Juni et al., 1999; Shea et al., 2009). We used these AMSTAR 2 percentage scores for descriptive purposes and to analyse associations of the methodological quality of SRs and predictors, which is justifiable.

Although there are some studies showing an association between a protocol and a better quality (Allers et al., 2018; Ge et al., 2018), we did not include the existence of a protocol as a predictor of quality because the existence of a protocol is one of the critical items in AMSTAR 2.

The restriction in the search to a five years period was undertaken to facilitate inclusion of a current sample of published SRs. It is likely that the patterns observed would continue to pertain if the time period were to be extended. In addition we only included SR in English or German, due to a lack of other language skills by enough members of our group. However only one SR was excluded during the full-text review due to language restraints.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lydia Jones for assistance with language editing and proofreading.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Allers K., Hoffmann F., Mathes T., Pieper D. Systematic reviews with published protocols compared to those without: more effort, older search. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018;95:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker L.A., Oxman A.D. Chapter 22: overviews of reviews. In: Higgins J.P.T., Green S., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2015. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] [Google Scholar]

- Burda B.U., Holmer H.K., Norris S.L. Limitations of A Measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR) and suggestions for improvement. Syst. Rev. 2016;5:58. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faggion C.M., Jr. Critical appraisal of AMSTAR: challenges, limitations, and potential solutions from the perspective of an assessor. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015;15:63. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming P.S., Koletsi D., Seehra J., Pandis N. Systematic reviews published in higher impact clinical journals were of higher quality. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014;67:754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L., Tian J.H., Li Y.N., Pan J.X., Li G., Wei D., Xing X., Pan B., Chen Y.L., Song F.J., Yang K.H. Association between prospective registration and overall reporting and methodological quality of systematic reviews: a meta-epidemiological study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018;93:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldkuhle M., Narayan V.M., Weigl A., Dahm P., Skoetz N. A systematic assessment of Cochrane reviews and systematic reviews published in high-impact medical journals related to cancer. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasuike A., Ueno D., Nagashima H., Kubota T., Tsukune N., Watanabe N., Sato S. Methodological quality and risk-of-bias assessments in systematic reviews of treatments for peri-implantitis. J. Periodontal. Res. 2019;54:374–387. doi: 10.1111/jre.12638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho R.S., Wu X., Yuan J., Liu S., Lai X., Wong S.Y., Chung V.C. Methodological quality of meta-analyses on treatments for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional study using the AMSTAR (Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews) tool. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2015;25:14102. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis J.P. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 2016;94:485–514. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juni P., Witschi A., Bloch R., Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1999;282:1054–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedzior K.K., Kaplan I. Tai Chi and Parkinson’s disease (PD): a systematic overview of the scientific quality of the past systematic reviews. Compl. Ther. Med. 2019;46:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq V., Beaudart C., Ajamieh S., Rabenda V., Tirelli E., Bruyere O. Meta-analyses indexed in PsycINFO had a better completeness of reporting when they mention PRISMA. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019;115:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq V., Beaudart C., Tirelli E., Bruyere O. Psychometric measurements of AMSTAR 2 in a sample of meta-analyses indexed in PsycINFO. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020;119:144–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Li W., Wan Y., Ren J., Li T., Li C. Appraisal of the methodological quality and summary of the findings of systematic reviews on the relationship between SSRIs and suicidality. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2014;26:248–258. doi: 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.214080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P.A., Clarke M., Devereaux P.J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions. Explanation and elaboration. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz R.C., Matthias K., Pieper D., Wegewitz U., Morche J., Nocon M., Rissling O., Schirm J., Jacobs A. A psychometric study found AMSTAR 2 to be a valid and moderately reliable appraisal tool. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019;114:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthias K., Lorenz R., Rissling O., Jacobs A., Morche J., Nocon M., Schirm J., Wegewitz U., Pieper D. 2018. Appraisal of the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews on Pharmacological and Psychological Interventions for Major Depression in Adults Using the AMSTAR.https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018110214 CRD42018110214. [Google Scholar]

- Pieper D., Puljak L., Gonzalez-Lorenzo M., Minozzi S. Minor differences were found between AMSTAR 2 and ROBIS in the assessment of systematic reviews including both randomized and nonrandomized studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019;108:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pussegoda K., Turner L., Garritty C., Mayhew A., Skidmore B., Stevens A., Boutron I., Sarkis-Onofre R., Bjerre L.M., Hrobjartsson A., Altman D.G., Moher D. Identifying approaches for assessing methodological and reporting quality of systematic reviews: a descriptive study. Syst. Rev. 2017;6:117. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pussegoda K., Turner L., Garritty C., Mayhew A., Skidmore B., Stevens A., Boutron I., Sarkis-Onofre R., Bjerre L.M., Hrobjartsson A., Altman D.G., Moher D. Systematic review adherence to methodological or reporting quality. Syst. Rev. 2017;6:131. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0527-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D.B., Shrier I., Kloda L.A., Benedetti A., Thombs B.D. Methodological quality of meta-analyses of the diagnostic accuracy of depression screening tools. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016;84:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A., Rankin J., Beaman J., Murray K., Sinnett P., Riddle R., Haskins J., Vassar M. Methodological quality of systematic reviews referenced in clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of opioid use disorder. PloS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181927. e0181927-e0181927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Oremus M. PRISMA and AMSTAR show systematic reviews on health literacy and cancer screening are of good quality. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018;99:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea B.J., Grimshaw J.M., Wells G.A., Boers M., Andersson N., Hamel C., Porter A.C., Tugwell P., Moher D., Bouter L.M. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea B.J., Hamel C., Wells G.A., Bouter L.M., Kristjansson E., Grimshaw J., Henry D.A., Boers M. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea B.J., Reeves B.C., Wells G., Thuku M., Hamel C., Moran J., Moher D., Tugwell P., Welch V., Kristjansson E., Henry D.A. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekelle P.G., Ortiz E., Rhodes S., Morton S.C., Eccles M.P., Grimshaw J.M., Woolf S.H. Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated? J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2001;286:1461–1467. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.12.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shojania K.G., Sampson M., Ansari M.T., Ji J., Doucette S., Moher D. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007;147:224–233. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-4-200708210-00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H., Zhang Y., Li Q., Chen J. Methodological quality evaluation of systematic reviews or meta-analyses on ERCC1 in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:2245–2256. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2516-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J., Zhang J., Ge L., Yang K., Song F. The methodological and reporting quality of systematic reviews from China and the USA are similar. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017;85:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gotzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P., Initiative S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegewitz U., Weikert B., Fishta A., Jacobs A., Pieper D. Resuming the discussion of AMSTAR: what can (should) be made better? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016;16:111. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0183-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization WHO Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. 2017. https://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/prevalence_global_health_estimates/en/

- Yan P., Yao L., Li H., Zhang M., Xun Y., Li M., Cai H., Lu C., Hu L., Guo T., Liu R., Yang K. The methodological quality of robotic surgical meta-analyses needed to be improved: a cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019;109:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L., Sun R., Chen Y.L., Wang Q., Wei D., Wang X., Yang K. The quality of evidence in Chinese meta-analyses needs to be improved. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016;74:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Zhang Y., Kwong J.S., Zhang C., Li S., Sun F., Niu Y., Du L. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J. Evid. Base Med. 2015;8:2–10. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Sun M., Han S., Shen X., Luo Y., Zhong D., Zhou X., Liang F., Jin R. Acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhea: an overview of systematic reviews. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:8791538. doi: 10.1155/2018/8791538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Han J., Zhu Y.B., Lau W.Y., Schwartz M.E., Xie G.Q., Dai S.Y., Shen Y.N., Wu M.C., Shen F., Yang T. Reporting and methodological qualities of published surgical meta-analyses. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016;70:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Fan L., Zhang H., Wang M., Mei X., Hou J., Shi Z., Shuai Y., Shen Y. Is the best evidence good enough: quality assessment and factor Analysis of meta-analyses on depression. PloS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.