Abstract

BACKGROUND

Osteochondral lesion of talus is a broad term used to describe an injury or abnormality of the talar articular cartilage and adjacent bone. It arises from diverse causes, and although trauma is implicated in many cases, it does not account for the etiology of every lesion. Gout is a chronic arthritic disease caused by excess levels of uric acid in blood. Intraosseous deposition of monosodium urate in the clavicle, femur, patella and calcaneus was reported previously. Gout is common disease but rare at a young age, especially during teenage years. Osteochondral lesion caused by intra-articular gouty invasion is very rare.

CASE SUMMARY

We encountered a rare case of a 16-year-old male who has osteochondral lesion of the talus (OLT) with gout. He had fluctuating pain for more than 2 years. We could see intra-articular tophi with magnetic resonance image (MRI) and arthroscopy. We performed arthroscopic exploration, debridement and microfracture. Symptoms were resolved after operation, and bony coverage at the lesion was seen on postoperative images. We had checked image and uric acid levels for 18 mo.

CONCLUSION

It is rare to see OLT with gouty tophi in young adults. While it is challenging, the accuracy of diagnosis can be improved through history taking, MRI and arthroscopy.

Keywords: Ankle, Gout, Osteochondral lesion of the talus, Tophi, Magnetic resonance image, Arthroscope, Case report

Core tip: Osteochondral lesion of talus (OLT) is usually known as a posttraumatic or repetitive stress lesion. It is rare to see OLT caused by gout tophi deposition. Furthermore, it is extremely rare in young adult or the adolescent. This case highlights the thorough history taking, radiologic study and arthroscopic finding for diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Osteochondral lesion of talus (OLT) is used to term abnormal lesion of talar articular cartilage and adjacent bone[1]. A lesion can also be categorized by its location on the articular surface of the talus as medial, lateral, or central with added subdivisions into anterior, central, or posterior as advocated by some authors[2]. While the exact incidence of symptomatic OLTs is unknown, they are quite prevalent and a significant source of ankle morbidity[3]. OLT arises from diverse causes, and although trauma is implicated in many cases, it does not account for the etiology of every lesion.

Gout is a chronic arthritic disease caused by abnormal uric acid metabolism. The findings of several studies suggest that the prevalence and incidence of gout has risen in recent decades[4]. A resurgence of gout across the population has been noted in recent years, and juvenile gout has also been reported, with many of the cases being due solely to known risk factors such as being overweight. Approximately 12%-35% of the gout patients develop tophi[5]. Although the disease normally results in the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in the connective tissue, kidney, and skin, intraosseous deposition of monosodium urate can occur in the clavicle, femoral condyle, metatarsal bone, sesamoid bone, phalanges, patella, calcaneus, vertebral body, and talus[6]. Osteochondral lesion caused by intra-articular gouty invasion is very rare. We were hard to find a similar case. We report the rare case of osteochondral lesion of the talus with gout in a teenage boy.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 16-year-old male patient complained of a painful left ankle on the anteromedial side for more than 2 years. He presented to the out-patient department on November 2016.

History of present illness

Pain levels fluctuated, and the maximum pain was 7 on visual analogue scale and persisted over a week.

History of past illness

The patient’s height is 168 cm and weight is 75 kg (body mass index: 26.57 kg/m2). He did not have any underlying medical history. He visited local hospitals several times and was diagnosed with osteochondral lesion of the talus through radiologic study. The symptom was alleviated with medication or rest. He had no trauma history, genetic predisposition or degenerative joint disease.

Physical examination

The patient did not have limitation of ankle range of motion. He had problem of weight bearing walking due to pain.

Laboratory examinations

There were no specific findings in preoperative laboratory examination.

Imaging examinations

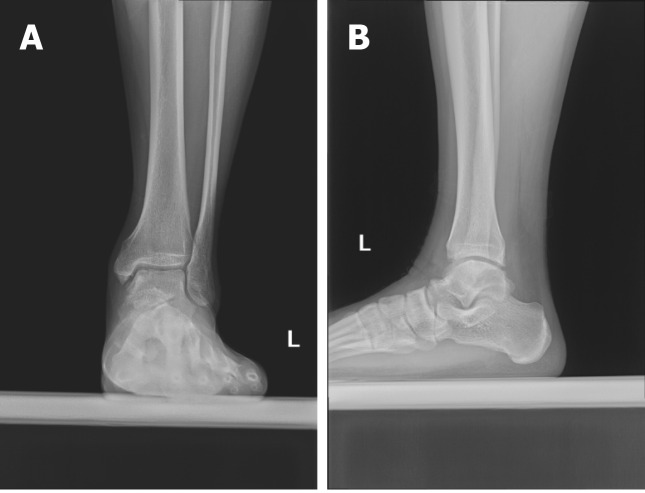

We found bony abnormalities, including OLTs in the equator of the medial talar dome with subchondral cyst, in the X-ray of ankle (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance image (MRI) was evaluated and found OLTs in the medial talar dome with subchondral cysts and subcortical depression. Also, we could see bony spurs at the anterior and posterior lips of the tibial plafond and tiny subchondral cyst at the anterior lip of the tibial plafond in MRI study (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The osteochondral lesion of talus of left ankle was found on medial talar dome (A and B).

Figure 2.

T1-weighted images of ankle magnetic resonance image. Osteochondral lesion of the talus in medial talar dome is seen in axial (A), coronal (B), and sagittal view (C).

Impression

The primary impression of the presented case is osteochondral lesion of the talus.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the case is osteochondral lesion of the talus due to gout tophi deposition.

TREATMENT

Operation was performed under supine position and spinal anesthesia. We used pneumatic tourniquet for preventing bleeding. Using an ankle arthroscopy device, we checked the ankle joint and the lesion. We found intra-articular gout tophi deposition in OLT during operation (Figure 3). Arthroscopic debridement was performed using ring curette. We performed synovectomy using shaver. Microfracture was performed using 60 degree awl. We excised the suspected lesions and sent the specimens for pathologic examination.

Figure 3.

Images of arthroscope were taken during operation. A: Ankle arthroscopic findings shows tophaceous lesion in the ankle joint; B: Tophaceous lesion was removed. C: Osteochondral defect was checked; D: Microfracture was perfomed.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After operation, ankle motion exercise (plantar flexion, dorsiflexion) was started with non-weight bearing ambulation. Weight-bearing ambulation was allowed at postoperative 4 wk.

After operation, uric acid level was checked as 11.7 mg/dL for the first time. Pathologic examination show fragments of fibrocollagenous tissue with cystic myxoid degeneration (Figure 4). We use febuxostat 40 mg once a day for controlling uric acid level postoperatively.

Figure 4.

The histologic findings show fragments of fibrocollagenous tissue with cystic myxoid degeneration.

At postoperative 1.5 years assessment (July 2018), pain was almost subsided as VAS 1, and the patient returned athletic activity. Uric acid level was well controlled (5.8 mg/dL) (Figure 5). We discovered improvement of OLT lesions through the bony defect coverage on postoperative X-ray (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Postoperative uric acid level had decreased gradually.

Figure 6.

Covered osteochondral lesion was seen on standing AP and lateral ankle X-ray images at 1.5 years after operation (A and B).

DISCUSSION

OLT occur in the articular cartilage and subchondral bone of the talus and are commonly associated with ankle injuries, such as sprains and fractures[7]. The etiology of OLTs in patients without a history of trauma remains unknown. The patient has no trauma history or congenital factors. Symptoms of OLT vary from complaints of severe pain to occasional findings of radiation without any symptoms. The patient complained of pain during walking, locking, edema of the ankle and other assorted ailments. The duration of symptoms is several minutes or days[8]. The patient presented in our study had fluctuating pain.

Gout lesions with joint localization may cause destruction and deformities, and also tophi may be inflamed or ulcerated. The primary treatment of tophaceous gout is to control the disease by medical treatment (xanthine oxidase inhibitor, allopurinol). However, if there is cosmetic deformation, functional disorder, or sinus drainage, surgical intervention is inevitable[9]. The patient had a family history of gout, with his father being diagnosed as well. We did not know exact family history at preoperative time.

If gouty tophi are present, MRI is able to detect this as a potentially differentiating characteristic. Tophi is typically seen low signal on T1-weighted (T1w) images and medium to high signal on T2-weighted (T2w) images, often seen surrounded cellular tissue and the crystalline mass. The vascularity of this tissue will influence the post-contrast enhancement MRI image, and calcification within the tophus can lead to regions of low signal on T2w images[10]. The patient shows low signal on T1w images and high signal on T2w images. This could indicate suspicious tophi in OLT, but there is no massive tophaceous lesion in MRI.

Although MRI is considered highly accurate in determining cartilage status[11-13], Lee et al[13] reported that there was a difference between MRI and arthroscopic findings. Arthroscopy was essential in determining the treatment strategy besides MRI[11-13]. Dual energy computed tomography (DECT) is a relatively new development in imaging of gout arthritis. DECT is a noninvasive method for the visualization, characterization, and quantification of monosodium urate crystal deposits. As a result, it helps the clinician in early diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of this condition. Usability and usage have become increasingly widespread in recent years. Unfortunately, DECT was not used in the patient[14].

Some intra-osseous tophi lesion were reported[15-19]. However, osteochondral lesion caused by intra-articular gouty invasion is extremely rare in young age. We did not find similar case anywhere. The patient’s MRI showed bony erosion produced by intra-articular tophaceous material. Suspicious tophi lesions might be overlooked. Therefore, a meticulous radiologic image check was needed for exact diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

It is rare to see OLT with gout in young adults. However, metabolic disease, such as gout, may be considered for diagnosis of OLT at a young age. While it is challenging, the accuracy of diagnosis can be improved through history taking, MRI and arthroscopy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank everyone who generously agreed to be interviewed for this research.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s mother for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: May 7, 2020

First decision: May 15, 2020

Article in press: August 12, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Öztürk R S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Taeho Kim, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam 13497, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea.

Young-Rak Choi, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul 05505, South Korea. jeanguy@hanmail.net.

References

- 1.Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Karlsson J. Osteochondral lesions of the talus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:2719–2720. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elias I, Zoga AC, Morrison WB, Besser MP, Schweitzer ME, Raikin SM. Osteochondral lesions of the talus: localization and morphologic data from 424 patients using a novel anatomical grid scheme. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:154–161. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandlin MI, Charlton TP, Taghavi CE, Giza E. Management of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus. Instr Course Lect. 2017;66:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roddy E, Doherty M. Epidemiology of gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:223. doi: 10.1186/ar3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasper IR, Juriga MD, Giurini JM, Shmerling RH. Treatment of tophaceous gout: When medication is not enough. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45:669–674. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morino T, Fujita M, Kariyama K, Yamakawa H, Ogata T, Yamamoto H. Intraosseous gouty tophus of the talus, treated by total curettage and calcium phosphate cement filling: a case report. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:126–128. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seo SG, Kim JS, Seo DK, Kim YK, Lee SH, Lee HS. Osteochondral lesions of the talus. Acta Orthop. 2018;89:462–467. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2018.1460777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong BO, Jung H. Arthroscopic Treatment for an Osteochondral Lesion of the Talus. J Korean Orthop Assoc. 2018;53:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Öztürk R, Atalay İB, Bulut EK, Beltir G, Yılmaz S, Güngör BŞ. Place of orthopedic surgery in gout. Eur J Rheumatol. 2019;6:212–215. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2019.19060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalbeth N, Doyle AJ. Imaging of gout: an overview. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26:823–838. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mintz DN, Tashjian GS, Connell DA, Deland JT, O'Malley M, Potter HG. Osteochondral lesions of the talus: a new magnetic resonance grading system with arthroscopic correlation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:353–359. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stroud CC, Marks RM. Imaging of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000;5:119–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee WC, Shim HC, Choi DS. MRI and arthroscopy of osteochondral lesion of the talus which was not visible on plain radiography. J Korean Society Foot Surg. 2002;6:195–200 (in Korean). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou H, Chin TY, Peh WC. Dual-energy CT in gout - A review of current concepts and applications. J Med Radiat Sci. 2017;64:41–51. doi: 10.1002/jmrs.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su CH, Hung JK. Intraosseous Gouty Tophus in the Talus: A Case Report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55:288–290. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung A, Allardice G. Intraosseous talar pseudotumour: an unusual presentation of gout. Foot (Edinb) 2013;23:86–87. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frykberg RG, Noe B, Michael S, Tierney E. Intra-osseous gout in a diabetic patient. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;48:70–73. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vetter SY, Simon R, von Recum J, Wentzensen A, Spiethoff A, Frank CB. Cystic pseudotumours in both upper ankle joints in gouty arthritis. Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;14:229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raikin S, Cohn BT. Intraosseous gouty invasion of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18:439–442. doi: 10.1177/107110079701800712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]