Abstract

Recent advances in our understanding of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the associated acute respiratory distress syndrome might approximate the cytokine release syndrome of severe immune-mediated disease. Importantly, this presumption provides the rationale for utilization of therapy, until recently reserved mostly for autoimmune diseases (ADs), in the management of COVID-19 hyperinflammation condition and has led to an extensive discussion for the potential benefits and detriments of immunosuppression. Our paper intends to examine the available recommendations, complexities in diagnosis and management when dealing with patients with ADs amidst the COVID-19 crisis. Mimicking a flare of an underlying AD, overlapping pathological lung patterns, probability of higher rates of false-positive antibody test, and lack of concrete data are only a part of the detrimental and specific characteristics of COVID-19 outbreak among the population with ADs. The administration of pharmaceutical therapy should not undermine the physical and psychological status of the patient with the maximum utilization of telemedicine. Researchers and clinicians should be vigilant for upcoming research for insight and perspective to fine-tune the clinical guidelines and practice and to weigh the potential benefits and detrimental effects of the applied immunomodulating therapy.

Keywords: Autoimmune diseases, Autoimmunity, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Serologic Tests, Cross reactions

Core tip: It is of utmost importance to differentiate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) manifestations from a relapse of the autoimmune disease. COVID-19 lung disease and interstitial lung disease may share similar pathological patterns. False positivity may complicate the serodiagnostics of COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune diseases. Maximum utilization of tele-medicine should be made when appropriate. Suspected COVID-19 patients should be treated by a multidisciplinary team with robust knowledge of immunosuppressive medication to carefully weigh the benefits and potential detrimental effects of the applied therapy.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has exponentially increased not only in numbers but in range of distribution causing a global threat to modern societies across the globe. Classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization, the COVID-19 outbreak has taken the lives of approximately 280000 people contracting more than 4 million, as of May 13, 2020[1]. The seriousness of this catastrophe necessitates an urgent, international, and multidisciplinary approach to bring about a change in the status quo achieving the much-needed catharsis in the theory and practice of diagnosis and management of COVID-19.

Advances in our understanding of COVID-19 have shown that tissue injury in severe and critically-ill patients is mediated by an overexuberant immune-mediated inflammatory response. This finding supports the rationale for searching a COVID-19-modifying drug not only in the long list of known antivirals but also among immune-modulating/suppressing drugs used in the management of autoimmune diseases (ADs)[2,3]. Our hypothesis is supported by a quick trial search through the United States National Library of Medicine (ClinicalTrials.gov) and the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (http://www.chictr.org.cn) where clear intentions for the repurposing of multiple immunosuppressive drugs could be found. The preliminary results look promising but further trials are warranted.

Our narrative review aims at presenting the complexities in diagnosis and management when dealing with patients with ADs amidst the COVID-19 crisis and commenting on the potential benefits and detriments of immunosuppression according to the leading societies dealing with ADs.

SEARCH METHODOLOGY

We conducted a literature search in the scientific databases Medline (PubMed) and Scopus and used the search engine Google Scholar to identify preprints. In PubMed and Scopus, both MeSH and relevant free-text terms were used. Recommendations for COVID-19 management from leading societies and teams handling ADs were retrieved. Given the innovative character of the data, relevant information was also included from preprints based on the authors’ perspective. Recommendations for writing a narrative review were followed[4]. Our search was confined to articles published from January 2020 to May 2020. Older publications were also cited to provide contextual background. References of retrieved publications were further hand-searched for supplements.

DIAGNOSIS OF COVID-19 IN PATIENTS WITH ADS

With the expansion of the COVID-19 outbreak, its coexistence with an autoimmune disease is not a special case anymore. As of May 13, 2020, the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance has reported 872 cases of rheumatic patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[5] and this number probably represents only the tip of the iceberg.

COVID-19: Mimicking the flare of an autoimmune disease

Diagnosing a viral infection in patients with an already established immune-mediated disease might present a major challenge to the practicing physician. This assumption comes from the fact that its first symptoms could resemble a possible AD flare[3]. However, in the case of COVID-19, there are further issues that need to be addressed.

Given the range of manifestations, the concept of COVID-19 has recently evolved from a monochromic disease to a “spectrum of disease” - a term that is commonly used in polysyndromic ADs. In fact, without any clear epidemiological data suggesting the diagnosis of COVID-19, the manifestation of nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, fever, myalgia, and arthralgia in a rheumatic patient would normally alert the rheumatologist for a possible relapse of the underlying autoimmune disease. Furthermore, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia, present in approximately 2/3 of the cases[6], interstitial lung disease, generalized rashes and vasculitis-like manifestations may further resemble an AD flare[7]. Importantly, this assumption poses an undefined threat to those contracting the virus. Escalation of immunosuppressive treatment may put the patient at higher risk for severe viral infection by suppressing the adaptive immune system and thus inhibiting viral clearance[8]. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to differentiate COVID-19 manifestations from relapse in patients with established autoimmune disease.

COVID-19 lung involvement and interstitial lung disease in ADs

Lung hyperinflammation and associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is thought to be the leading cause of death in patients with COVID-19[9]. Pathological changes in the lungs of patients with COVID-19 driven ARDS are dominated by overreacted T-cells[10] causing a "cytokine storm" which plays an essential and commanding role in the disease pathogenesis and clinical outcome[6]. These pathological findings remind us of a severe immune-mediated disorder. Interestingly, the patchy or diffuse pattern of the COVID-19 interstitial pneumonia sounds like “deja vu” to rheumatologists mimicking connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung diseases (CTD-ILDs). More importantly, it has already been suggested that CTD-ILDs and COVID-19 ARDS share the same histomorphological, serological, and radiological features triggering organ-specific autoimmunity in predisposed patients[11]. It should be also noted that hyperferritinemia, until recently reserved for a group of diseases with predominantly autoimmune genesis[12], has become a pathognomic feature of the cytokine storm mainly confined to the lung parenchyma[13].

Hypergammaglobulinemia in ADs and serological tests - a prerequisite for cross-reactivity

Although reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) remains the “gold standard” for diagnosing COVID-19[14], serological tests could serve as a complement to nucleic acid testing for the detection of suspected cases with negative RT–PCR results and in screening for asymptomatic contagious individuals in close contacts[15]. Those antibody tests are widely available and have relatively lower costs, require almost no highly-specialized equipment, and are time-sparing, therefore affordable.

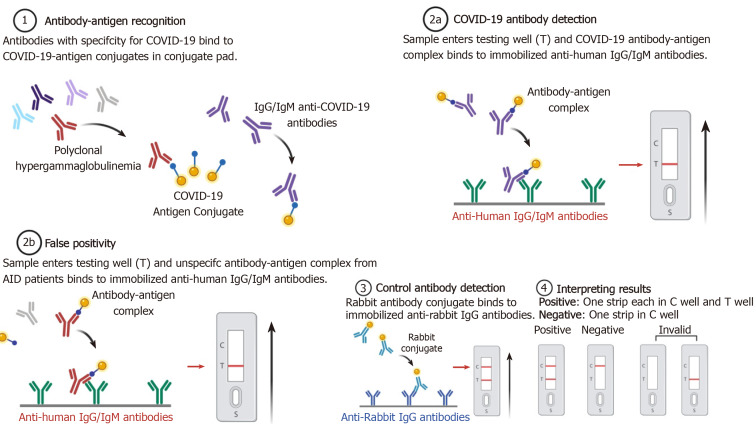

Notwithstanding that false-negative tests are a major concern at the population level, false positivity may present a diagnostic issue pertaining to patients with ADs. Diagnostic concerns come from the fact that, as a result of polyclonal hypergamma-globulinemia, patients with immune-mediated diseases and particularly those with autoimmune conditions may produce false-positive results for SARS-CoV2-IgG and IgM. Virus-specific antibody detection testing for the SARS-CoV-IgG and IgM has already shown false-positive results in patients with the following ADs - systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, mixed connective tissue disease, and rheumatoid arthritis[16]. This list is probably inconclusive since cross-reaction may be common in ADs with polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (Figure 1). Further studies are warranted to confirm or reject this hypothesis. Interestingly, the “vice versa” phenomenon has already been observed: Low titers of transient ADs-specific or -associated autoantibodies may be present in common viral infections[17]. In a small study taking place in intensive care units, elevated serum titers of antinuclear autoantibodies were observed in over 90% of COVID-19 patients[12]. Furthermore, anticardiolipin IgA antibodies and anti–β2-glycoprotein I IgA and IgG antibodies present frequently in sera of patients with COVID-19 and no previous history of ADs[18]. Another recent study showed that 20% of patients with COVID-19 had a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time due to lupus anticoagulant associated with thromboses[19].

Figure 1.

Viral antibody detection testing and hypothetical case of false-positive cross-reactivity in patients with autoimmune diseases and related polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (created with BioRender.com). COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019.

MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH ADS AMIDST THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Patients with ADs may have increased susceptibility to COVID-19 due to the underlying disorder, increased comorbidity, and ongoing therapy with immunosuppressive, immunomodulating, and/or glucocorticoid agents. Decisions about treatment should be made by an interdisciplinary team of experts because data is insufficient and recommendations are made on a speculative basis[20]. Reduction of visits to the clinic and maximum utilization of tele-medicine should be made when appropriate. This is a ripe time for building a good infrastructure for a more convenient and cost-effective way to treat patients forthwith and in the future[21-39] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Guidance, recommendations, and statements for management of patients with autoimmune diseases

| Disease spectrum | AAD[22] | ACR[23] | AFEF[24] | BCR and NICE[25,26] | BSG[27] | Ceribelli et al[28] | EASL-ESCMID[29] | ECCO[30,31] | EULAR[32] | IPC[33] | Lleo et al[34] | MSIF[35] | Sarzi-Puttini et al[36] | SGEI, ISG and INASL[37] | SIN[38] | Torres et al[39] |

| RD | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| ADD | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| AIH | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| IBD | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| MS | X | X |

AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; ADD: Autoimmune dermatological disease; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; MS: Multiple sclerosis; RD: Rheumatic disease; AAD: American Academy of Dermatology; ACR: American college of rheumatology; AFEF: French Association for the Study of the Liver; BCR: British Society for Rheumatology; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; BSG: British Society of Gastroenterology; EASL: European Association for the Study of the Liver; ESCMID: European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; ECCO: European Crohn's and Colitis Organization; EULAR: European League Against Rheumatism; IPC: International Psoriasis Council; MSIF: Multiple Sclerosis International Federation; SGEI: Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy of India; ISG: India Society of Gastroenterology; INASL: Indian National Association for the Study of the Liver; SIN: Italian Society of Neurology.

Psychological and physical management

It is well established in the literature that a large percentage of people with ADs suffer from depression and other health-related quality of life impairments[40]. As the pandemic situation progresses the data is relatively limited for how this restricted lifestyle will affect the population, but it can be presumed that it will unlock or exacerbate existing mental health conditions. The problem must be tackled on multiple levels with a wide array of interventions[41]. Applicable/appropriate recommendations should be made on the usage of all available online platforms, hotlines, mindful practices, local or national resources for dealing with mental health issues. With today’s available technology isolation should only be physical not social, mental, spiritual, or emotional[42]. However, measures on restriction of free movement do not mean limitation of physical activity and all forms of exercise. All kinds of exercise regimens should be emphasized to counter the lack of everyday dynamics as prolonged sedentary behavior can increase anxiety and depression[43]. High-tech tools as mobile applications, games, and video formats can be utilized to meet the recommended levels of activity[44]. Physical activity and exercise can be a very versatile intervention as it addresses the mental state, comorbidity and manages disease activity in ADs[45,46] Attention should be given to patients in a more frail state and joint conditions with specific exercise regimens. Because the lack of direct access to treatment and physician care implementation of online platforms is warranted, but a major limitation remains the lack of digital savviness/proficiency and the absence of technology in certain groups like the elderly.

Pharmaceutical management

Treatment of COVID-19 is a rapidly developing matter, as for now, there is no high-quality evidence to back a concrete regimen[47]. The potential effect of immunosuppressive and anti-cytokine drugs has been extensively discussed but the potentially detrimental consequences of reducing inflammation in a critically ill patient should be carefully weighed[8,48-52]. Consensus for the treatment of patients with a rheumatic disease with presumptive COVID-19 is that immunosuppression should be stopped temporarily but chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine (HCQ/CQ) may be continued[23]. In the ideal clinical practice, monitoring the immune system status of the patient would provide useful insight into the polyphasic nature of COVID-19 and give us an opportunity to apply adequate therapy depending on the stage: Specific antivirals and stimulation of type-I Interferon in the early phase, suppression of hyperinflammation in the subsequent phase[50]. Modulation of the inflammatory state with Interleukin-6 (IL-6) antagonists and JAK/STAT inhibitors among others is a potentially viable strategy to treat CRS and ARDS that is being intensively researched[50,52-54].

The antimalarial drugs CQ and HCQ are one of the medications that arguably gained the most traction for the possible treatment of COVID-19. With promising theoretical and small clinical study data, it sparked a hope for the sought after miracle cure. However, overall data on the subject is conflicting[55]. As the evidence for the treatment of COVID-19 progressed a problem emerged facing the patients with ADs – medical supply shortage particularly for HCQ[56]. Stopping intake can lead to a disease flare which can have deleterious effects that can increase morbidity and mortality[57]. As for the potential benefits of the treatment from data on patients without ADs, we may extrapolate that there may be a possible effect on large number of patients who develop radiographic progression and reduction of symptomatic days, but an additional benefit of the addition of Azithromycin (AZ) to therapy is uncertain[58]. A retrospective analysis of 1061 patients concluded that HCQ and AZ combination is safe and is correlated with a low fatality rate[59]. An observational study of 1446 patients showed no significant effect and suggested removal of HCQ from the clinical guide[60]. More data from high-quality randomized control trials are needed to assess the efficacy of antimalarial drugs[61]. Prospective studies are being advocated to establish the potency of prophylaxis and the correct time-window of HCQ administration[62]. Caution should be taken when interpreting the data and consider the possible side effects[63]. The complex overlap of medication used in autoimmune disease and the proposed coronavirus treatments like HCQ presents an interesting question: Does chronic therapy provide protection? Preliminary data in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) suggests that HCQ does not prevent COVID-19[64,65].

In the course of an infection glucocorticoid therapy should not be abruptly stopped[23]. Patients on ≥ 5 mg prednisolone or equivalent per day for ≥ 1 mo and prior chronic therapy > 3 mo are at risk of hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression and adrenal insufficiency[66,67]. If symptoms of COVID-19 such as fever or dry cough develop daily oral dosage should be doubled or physiological stress doses of 50-100 mg of hydrocortisone t.i.d can be utilized[67]. Caution and case by case clinical judgement should be taken as corticosteroid therapy can delay viral clearing[68]. Glucocorticoids are not recommended for the general treatment of any viral pneumonia including COVID-19 unless indicated for another reason[69].

An upcoming clinical trial will test the efficacy of colchicine in COVID-19 clinical course[70]. Colchicine has been used in vasculitis and gout but recently it has emerged as a potential new treatment for atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular disease with its inhibition of the most studied subset of inflammasomes the nod-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3[71].

Biological therapy continuation in patients with ADs should be evaluated on specific case basis, as currently there is not enough evidence for making a specific recommendation[72]. Nonetheless, data from COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician registry suggest that treatment with biologics were not associated with a higher risk of hospitalisation for COVID-19[73].

CONCLUSION

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the diagnostics and management of ADs are hindered. Complex mechanisms of the underlying disease interplay to create pitfalls in the diagnostic process. Management should not only be pharmaceutical but physical and psychological with maximum utilization of telemedicine. Rapid advances in the understanding of COVID-19 and the potential benefits of immunosuppressive/ immunomodulating therapy are being extensively discussed but as of yet there is not enough information for a concrete treatment protocol. We should be vigilant for upcoming research for insight and perspective to fine-tune our clinical guidelines and practice. Suspected COVID-19 patients should be treated by a multidisciplinary team with robust knowledge of immunosuppressive medication to carefully weigh the benefits and potential detrimental effects of the applied therapy.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflict of interest to declare for both authors.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: May 16, 2020

First decision: June 7, 2020

Article in press: August 26, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Bulgaria

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Firinu D S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

Contributor Information

Tsvetoslav Georgiev, Clinic of Rheumatology, University Hospital "St. Marina", First Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University - Varna, Varna 9010, Bulgaria. tsetso@medfaculty.org.

Alexander Krasimirov Angelov, Clinic of Rheumatology, University Hospital "St. Ivan Rilski", Medical University - Sofia, Sofia 1612, Bulgaria.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation Report-113. 2020 [cited 13 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200512-covid-19-sitrep-113.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georgiev T. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and anti-rheumatic drugs. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:825–826. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04570-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Blackmore H, Kitas GD. Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:1409–1417. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1999-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance. 2020 [cited 13 May 2020]. Data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance Global Registry. Available from: https://rheum-covid.org/updates/combined-data.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misra DP, Agarwal V, Gasparyan AY, Zimba O. Rheumatologists' perspective on coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) and potential therapeutic targets. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:2055–2062. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05073-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritchie AI, Singanayagam A. Immunosuppression for hyperinflammation in COVID-19: a double-edged sword? Lancet. 2020;395:1111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30691-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson PG, Qin L, Puah S. COVID-19 ARDS: clinical features and differences to “usual” pre-COVID ARDS. Med J Aust. 2020 doi: 10.5694/mja2.50674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, Liu S, Zhao P, Liu H, Zhu L, Tai Y, Bai C, Gao T, Song J, Xia P, Dong J, Zhao J, Wang FS. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gagiannis D, Steinestel J, Hackenbroch C, Hannemann M, Umathum VG, Gebauer N, Stahl M, Witte HM, Steinestel K. COVID-19-induced acute respiratory failure: an exacerbation of organ-specific autoimmunity? medRxiv. 2020:Preprint. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. Ferritin in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colafrancesco S, Alessandri C, Conti F, Priori R. COVID-19 gone bad: A new character in the spectrum of the hyperferritinemic syndrome? Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102573. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel A, Jernigan DB 2019-nCoV CDC Response Team. Initial Public Health Response and Interim Clinical Guidance for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak - United States, December 31, 2019-February 4, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:140–146. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6905e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long QX, Liu BZ, Deng HJ, Wu GC, Deng K, Chen YK, Liao P, Qiu JF, Lin Y, Cai XF, Wang DQ, Hu Y, Ren JH, Tang N, Xu YY, Yu LH, Mo Z, Gong F, Zhang XL, Tian WG, Hu L, Zhang XX, Xiang JL, Du HX, Liu HW, Lang CH, Luo XH, Wu SB, Cui XP, Zhou Z, Zhu MM, Wang J, Xue CJ, Li XF, Wang L, Li ZJ, Wang K, Niu CC, Yang QJ, Tang XJ, Zhang Y, Liu XM, Li JJ, Zhang DC, Zhang F, Liu P, Yuan J, Li Q, Hu JL, Chen J, Huang AL. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:845–848. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Sun S, Shen H, Jiang L, Zhang M, Xiao D, Liu Y, Ma X, Zhang Y, Guo N, Jia T. Cross-reaction of SARS-CoV antigen with autoantibodies in autoimmune diseases. Cell Mol Immunol. 2004;1:304–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen KE, Arnason J, Bridges AJ. Autoantibodies and common viral illnesses. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1998;27:263–271. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(98)80047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Xiao M, Zhang S, Xia P, Cao W, Jiang W, Chen H, Ding X, Zhao H, Zhang H, Wang C, Zhao J, Sun X, Tian R, Wu W, Wu D, Ma J, Chen Y, Zhang D, Xie J, Yan X, Zhou X, Liu Z, Wang J, Du B, Qin Y, Gao P, Qin X, Xu Y, Zhang W, Li T, Zhang F, Zhao Y, Li Y, Zhang S. Coagulopathy and Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowles L, Platton S, Yartey N, Dave M, Lee K, Hart DP, MacDonald V, Green L, Sivapalaratnam S, Pasi KJ, MacCallum P. Lupus Anticoagulant and Abnormal Coagulation Tests in Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:288–290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Askanase AD, Khalili L, Buyon JP. Thoughts on COVID-19 and autoimmune diseases. Lupus Sci Med. 2020;7:e000396. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2020-000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portnoy J, Waller M, Elliott T. Telemedicine in the Era of COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1489–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Academy of Dermatology. Clinical guidance for COVID-19. 2020 [cited 13 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coronavirus/clinical-guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikuls TR, Johnson SR, Fraenkel L, Arasaratnam RJ, Baden LR, Bermas BL, Chatham W, Cohen S, Costenbader K, Gravallese EM, Kalil AC, Weinblatt ME, Winthrop K, Mudano AS, Turner A, Saag KG. American College of Rheumatology Guidance for the Management of Rheumatic Disease in Adult Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Version 1. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/art.41301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganne-Carrié N, Fontaine H, Dumortier J, Boursier J, Bureau C, Leroy V, Bourlière M AFEF, French Association for the Study of the Liver. Suggestions for the care of patients with liver disease during the Coronavirus 2019 pandemic. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.COVID-19 Guidance. BSR guidance for patients during COVID-19 outbreak. 2020 [cited 13 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.rheumatology.org.uk/News-Policy/Details/Covid19-Coronavirus-update-members. [Google Scholar]

- 26.NICE. COVID-19 rapid guideline: rheumatological autoimmune, inflammatory and metabolic bone disorders. 2020 [13 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.British Society of Gastroenterology. BSG expanded consensus advice for the management of IBD during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020 [13 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.bsg.org.uk/covid-19-advice/bsg-advice-for-management-of-inflammatory-bowel-diseases-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ceribelli A, Motta F, De Santis M, Ansari AA, Ridgway WM, Gershwin ME, Selmi C. Recommendations for coronavirus infection in rheumatic diseases treated with biologic therapy. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102442. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boettler T, Newsome PN, Mondelli MU, Maticic M, Cordero E, Cornberg M, Berg T. Care of patients with liver disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: EASL-ESCMID position paper. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100113. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ECCO Taskforce. 1st Interview COVID-19. 2020 [13 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.ecco-ibd.eu/images/6_Publication/6_8_Surveys/1st_interview_COVID-19%20ECCOTaskforce_published.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.ECCO Taskforce. 2nd Interview COVID-19. 2020 [13 May 2020]. Available from: https://ecco-ibd.eu/images/6_Publication/6_8_Surveys/2nd_Interview_COVID-19_ECCO_Taskforce_published.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32.EULAR. EULAR guidance for patients COVID-19 outbreak. 2020 [13 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.eular. org/eular_guidance_for_patients_covid19_outbreak.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 33.International Psoriasis Council (IPC) Statement on the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak. 2020 [13 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.psoriasiscouncil.org/blog/Statementon-COVID-19-and-Psoriasis.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lleo A, Invernizzi P, Lohse AW, Aghemo A, Carbone M. Management of patients with autoimmune liver disease during COVID-19 pandemic. J Hepatol. 2020;73:453–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. The coronavirus and MS – global advice. 2020 [13 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.msif.org/news/2020/02/10/the-coronavirus-and-ms-what-you-need-to-know/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarzi-Puttini P, Marotto D, Antivalle M, Salaffi F, Atzeni F, Maconi G, Monteleone G, Rizzardini G, Antinori S, Galli M, Ardizzone S. How to handle patients with autoimmune rheumatic and inflammatory bowel diseases in the COVID-19 era: An expert opinion. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102574. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Philip M, Lakhtakia S, Aggarwal R, Madan K, Saraswat V, Makharia G. Joint Guidance from SGEI, ISG and INASL for Gastroenterologists and Gastrointestinal Endoscopists on the Prevention, Care, and Management of Patients With COVID-19. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020;10:266–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giovannoni G, Hawkes C, Lechner-Scott J, Levy M, Waubant E, Gold J. The COVID-19 pandemic and the use of MS disease-modifying therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;39:102073. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torres T, Puig L. Managing Cutaneous Immune-Mediated Diseases During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:307–311. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00514-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pryce CR, Fontana A. Depression in Autoimmune Diseases. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;31:139–154. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stein MB. EDITORIAL: COVID-19 and Anxiety and Depression in 2020. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37:302. doi: 10.1002/da.23014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen P, Mao L, Nassis GP, Harmer P, Ainsworth BE, Li F. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. J Sport Health Sci. 2020;9:103–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tate DF, Lyons EJ, Valle CG. High-tech tools for exercise motivation: use and role of technologies such as the internet, mobile applications, social media, and video games. Diabetes Spectr. 2015;28:45–54. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.28.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharif K, Watad A, Bragazzi NL, Lichtbroun M, Amital H, Shoenfeld Y. Physical activity and autoimmune diseases: Get moving and manage the disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17:53–72. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dinas PC, Koutedakis Y, Flouris AD. Effects of exercise and physical activity on depression. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180:319–325. doi: 10.1007/s11845-010-0633-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vijayvargiya P, Esquer Garrigos Z, Castillo Almeida NE, Gurram PR, Stevens RW, Razonable RR. Treatment Considerations for COVID-19: A Critical Review of the Evidence (or Lack Thereof) Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1454–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perricone C, Triggianese P, Bartoloni E, Cafaro G, Bonifacio AF, Bursi R, Perricone R, Gerli R. The anti-viral facet of anti-rheumatic drugs: Lessons from COVID-19. J Autoimmun. 2020;111:102468. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russell B, Moss C, George G, Santaolalla A, Cope A, Papa S, Van Hemelrijck M. Associations between immune-suppressive and stimulating drugs and novel COVID-19-a systematic review of current evidence. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1022. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2020.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu B, Li M, Zhou Z, Guan X, Xiang Y. Can we use interleukin-6 (IL-6) blockade for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-induced cytokine release syndrome (CRS)? J Autoimmun. 2020;111:102452. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jamilloux Y, Henry T, Belot A, Viel S, Fauter M, El Jammal T, Walzer T, François B, Sève P. Should we stimulate or suppress immune responses in COVID-19? Cytokine and anti-cytokine interventions. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102567. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arnaldez FI, O'Day SJ, Drake CG, Fox BA, Fu B, Urba WJ, Montesarchio V, Weber JS, Wei H, Wigginton JM, Ascierto PA. The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer perspective on regulation of interleukin-6 signaling in COVID-19-related systemic inflammatory response. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000930. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu X, Ong YK, Wang Y. Role of adjunctive treatment strategies in COVID-19 and a review of international and national clinical guidelines. Mil Med Res. 2020;7:22. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00251-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toniati P, Piva S, Cattalini M, Garrafa E, Regola F, Castelli F, Franceschini F, Airò P, Bazzani C, Beindorf EA, Berlendis M, Bezzi M, Bossini N, Castellano M, Cattaneo S, Cavazzana I, Contessi GB, Crippa M, Delbarba A, De Peri E, Faletti A, Filippini M, Filippini M, Frassi M, Gaggiotti M, Gorla R, Lanspa M, Lorenzotti S, Marino R, Maroldi R, Metra M, Matteelli A, Modina D, Moioli G, Montani G, Muiesan ML, Odolini S, Peli E, Pesenti S, Pezzoli MC, Pirola I, Pozzi A, Proto A, Rasulo FA, Renisi G, Ricci C, Rizzoni D, Romanelli G, Rossi M, Salvetti M, Scolari F, Signorini L, Taglietti M, Tomasoni G, Tomasoni LR, Turla F, Valsecchi A, Zani D, Zuccalà F, Zunica F, Focà E, Andreoli L, Latronico N. Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia with hyperinflammatory syndrome and acute respiratory failure: A single center study of 100 patients in Brescia, Italy. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102568. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guastalegname M, Vallone A. Could Chloroquine /Hydroxychloroquine Be Harmful in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment? Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:888–889. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michaud K, Wipfler K, Shaw Y, Simon TA, Cornish A, England BR, Ogdie A, Katz P. Experiences of Patients With Rheumatic Diseases in the United States During Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2:335–343. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aouhab Z, Hong H, Felicelli C, Tarplin S, Ostrowski RA. Outcomes of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Patients who Discontinue Hydroxychloroquine. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2019;1:593–599. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarma P, Kaur H, Kumar H, Mahendru D, Avti P, Bhattacharyya A, Prajapat M, Shekhar N, Kumar S, Singh R, Singh A, Dhibar DP, Prakash A, Medhi B. Virological and clinical cure in COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:776–785. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Million M, Lagier JC, Gautret P, Colson P, Fournier PE, Amrane S, Hocquart M, Mailhe M, Esteves-Vieira V, Doudier B, Aubry C, Correard F, Giraud-Gatineau A, Roussel Y, Berenger C, Cassir N, Seng P, Zandotti C, Dhiver C, Ravaux I, Tomei C, Eldin C, Tissot-Dupont H, Honoré S, Stein A, Jacquier A, Deharo JC, Chabrière E, Levasseur A, Fenollar F, Rolain JM, Obadia Y, Brouqui P, Drancourt M, La Scola B, Parola P, Raoult D. Early treatment of COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: A retrospective analysis of 1061 cases in Marseille, France. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;35:101738. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geleris J, Sun Y, Platt J, Zucker J, Baldwin M, Hripcsak G, Labella A, Manson DK, Kubin C, Barr RG, Sobieszczyk ME, Schluger NW. Observational Study of Hydroxychloroquine in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2411–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pastick KA, Okafor EC, Wang F, Lofgren SM, Skipper CP, Nicol MR, Pullen MF, Rajasingham R, McDonald EG, Lee TC, Schwartz IS, Kelly LE, Lother SA, Mitjà O, Letang E, Abassi M, Boulware DR. Review: Hydroxychloroquine and Chloroquine for Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa130. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Picot S, Marty A, Bienvenu AL, Blumberg LH, Dupouy-Camet J, Carnevale P, Kano S, Jones MK, Daniel-Ribeiro CT, Mas-Coma S. Coalition: Advocacy for prospective clinical trials to test the post-exposure potential of hydroxychloroquine against COVID-19. One Health. 2020;9:100131. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferner RE, Aronson JK. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in covid-19. BMJ. 2020;369:m1432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mathian A, Mahevas M, Rohmer J, Roumier M, Cohen-Aubart F, Amador-Borrero B, Barrelet A, Chauvet C, Chazal T, Delahousse M, Devaux M, Euvrard R, Fadlallah J, Florens N, Haroche J, Hié M, Juillard L, Lhote R, Maillet T, Richard-Colmant G, Palluy JB, Pha M, Perard L, Remy P, Rivière E, Sène D, Sève P, Morélot-Panzini C, Viallard JF, Virot JS, Benameur N, Zahr N, Yssel H, Godeau B, Amoura Z. Clinical course of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a series of 17 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus under long-term treatment with hydroxychloroquine. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:837–839. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Konig MF, Kim AH, Scheetz MH, Graef ER, Liew JW, Simard J, Machado PM, Gianfrancesco M, Yazdany J, Langguth D, Robinson PC COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance. Baseline use of hydroxychloroquine in systemic lupus erythematosus does not preclude SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bancos I, Hahner S, Tomlinson J, Arlt W. Diagnosis and management of adrenal insufficiency. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:216–226. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaiser UB, Mirmira RG, Stewart PM. Our Response to COVID-19 as Endocrinologists and Diabetologists. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:dgaa148. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li H, Chen C, Hu F, Wang J, Zhao Q, Gale RP, Liang Y. Impact of corticosteroid therapy on outcomes of persons with SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, or MERS-CoV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leukemia. 2020;34:1503–1511. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0848-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when COVID-19 is suspected. Interim guidance. 2020 [cited 13 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deftereos S, Giannopoulos G, Vrachatis DA, Siasos G, Giotaki SG, Cleman M, Dangas G, Stefanadis C. Colchicine as a potent anti-inflammatory treatment in COVID-19: can we teach an old dog new tricks? Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020;6:255. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.An N, Gao Y, Si Z, Zhang H, Wang L, Tian C, Yuan M, Yang X, Li X, Shang H, Xiong X, Xing Y. Regulatory Mechanisms of the NLRP3 Inflammasome, a Novel Immune-Inflammatory Marker in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1592. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bashyam AM, Feldman SR. Should patients stop their biologic treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:317–318. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1742438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al-Adely S, Carmona L, Danila MI, Gossec L, Izadi Z, Jacobsohn L, Katz P, Lawson-Tovey S, Mateus EF, Rush S, Schmajuk G, Simard J, Strangfeld A, Trupin L, Wysham KD, Bhana S, Costello W, Grainger R, Hausmann JS, Liew JW, Sirotich E, Sufka P, Wallace ZS, Yazdany J, Machado PM, Robinson PC COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance. Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:859–866. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]