Summary

Currently, more than 1,200 agrochemicals are listed and many of these are regularly used by farmers to generate the food supply to support the expanding global population. However, resistance to pesticides is an ever more frequently occurring phenomenon, and thus, a continuous supply of novel agrochemicals with high efficiency, selectivity, and low toxicity is required. Moreover, the demand for a more sustainable society, by reducing the risk chemicals pose to human health and by minimizing their environmental footprint, renders the development of novel agrochemicals an ever more challenging undertaking. In the last two decades, fluoro-chemicals have been associated with significant advances in the agrochemical development process. We herein analyze the contribution that organofluorine compounds make to the agrochemical industry. Our database covers 424 fluoro-agrochemicals and is subdivided into several categories including chemotypes, mode of action, heterocycles, and chirality. This in-depth analysis reveals the unique relationship between fluorine and agrochemicals.

Subject Areas: Chemistry, Industrial Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, Agricultural Science

Graphical Abstract

Chemistry; Industrial Chemistry; Organic Chemistry; Agricultural Science

Introduction

As the global population rapidly expands, it is essential to ensure sufficient crop production to feed this growing number of people. Crop production has continually suffered from problems associated with plant diseases, pests, parasites, fungi, viruses, and even recent drastic climate change. As such, agrochemicals (pesticides) such as herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides have played an essential role in maintaining crop yields and minimizing crop loss. Thus, the development of new agrochemicals has emerged as one of the foremost areas of research in modern agricultural industry (Krämer et al., 2012). Notably, the use of agrochemicals serves not only the protection of crops but also the protection of human health from parasitic infectious diseases such as malaria, Zika virus, and dengue fever, which are spread by mosquitos (Witschel et al., 2012).

Traditionally, agrochemicals were derived from natural products and inorganic materials. Over time, the use of synthetic organic agrochemicals, rather than inorganic chemicals and natural products, for the protection of crops has burgeoned (Marchand, 2019). In 1939, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), a historically notorious and controversial synthetic pesticide, marked the beginning of the era of synthetic agrochemicals (Figure 1A) (Simon, 1999). Notably, like the return of thalidomide in the 21st century to the pharmaceutical market to fight, e.g., leprosy (Ito and Handa, 2015; Tokunaga et al., 2018), DDT has returned in the 21st century to the agrochemical market under controlled conditions to combat malaria (Mandavilli, 2006). The effectiveness of DDT as a powerful and potent insecticide was discovered by Müller and led to the widespread use of DDT against mosquitoes and many other insects in the 1940s (it should be noted here that Müller was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1948 for his discovery) (Nobel Foundation, 1964). In 1945, a fluorinated analog of DDT, 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis(4-fluorophenyl)ethane (DFDT, fluoro-DDT, also called Gix, Fluorgesarol), which managed to avoid a patent conflict with DDT, was predominantly manufactured in Germany during World War II (Figure 1B) (Kilgore, 1945; Metcalf, 1948; Gunther and Blinn, 1950; Zhu et al., 2019). Interestingly, fluoro-DDT is a faster-acting congener of DDT for malaria, with high solubility, low toxicity to warm-blooded animals, and high volatility. However, the use of DDT, including fluoro-DDT, was prohibited following claims relating to the environmental and toxicological impact of pesticides published in Rachel Carson's book "Silent Spring" in 1962 (Carson, 1962). As mentioned, DDT has been revived under certain conditions, whereas fluoro-DDT has not. The “forgotten” history of DFDT has recently been discussed elsewhere (New York University, 2019).

Figure 1.

Early Examples of Synthetic Pesticides and Fluoro-pharmaceuticals

(A) DDT.

(B) DFDT.

(C) Trifluralin.

(D) Florinef acetate.

Currently, more than 1,200 agrochemicals are registered and used worldwide, including those discontinued (Turner, 2018). However, more sophisticated and efficient agrochemicals are constantly required for the protection of crops and to render human society more sustainable. This requires innovative, efficient, and selective agrochemicals that are less toxic and that have environmentally benign chemical properties; the latter is particularly important with respect to bioaccumulation. Currently, a new agrochemical cannot be approved unless its effects on air, water, soil, and human health are known (Vaz, 2019; Delorenzo et al., 2001; Ames and Gold, 1997; Bhattacharyya et al., 2009).

Inspired by the potential efficiency of fluoro-DDT as an insecticide, the first fluoro-herbicide, trifluralin (Epp et al., 2018) introduced by Eli Lilly & Co. in 1963 (Figure 1C, also one of the most globally used herbicides), as well as our ongoing research into biologically active organofluorine compounds (Shibata, 2016), we were interested in the contributions of fluorine-containing agrochemicals (fluoro-agrochemicals) to the wider field of agrochemicals (Cartwright, 1994; Theodoridis, 2006; Fujiwara and O' Hagan, 2014; Jeschke, 2004; Haufe and Leroux, 2019; Pazenok and Leroux, 2020). Organofluorine compounds have emerged as attractive synthetic building blocks in the pharmaceutical industry (Wang et al., 2014; Ojima, 2009) following the use of the first successful fluoro-pharmaceutical, Florinef acetate, in 1954 (Figure 1D). The introduction of fluorine and fluorine-containing functional groups into drug candidates is one of the principal approaches to effectively alter the physicochemical properties, such as acidity, lipophilicity, and stability, of a parent molecule. This alteration results in a modulation of the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of a drug (Ojima, 2009). The advantageous effects imparted by the addition of fluorine to pharmaceuticals are induced by a combination of several properties unique to fluorine: (1) fluorine is, after hydrogen, the second smallest atom; (2) fluorine exhibits the highest electronegativity in the periodic table of elements; (3) fluorine forms the strongest single bonds with carbon. Over the years, the contributions of organofluorine compounds to the pharmaceutical industry have increased steadily, and the total number of fluoro-pharmaceuticals approved for use reached 340 in 2019 (Inoue et al., 2020). Based on the record of introducing fluorine into pharmaceuticals, a similarly strong impact of fluorine onto the agrochemicals sector can be feasibly expected, although there are intrinsic differences between the role agrochemicals play for plants and insects and pharmaceuticals play for humans. However, the discovery process for new active compounds in the pharmaceutical and agrochemical sectors is notably very similar (Delaney et al., 2006; Swanton et al., 2011). These similarities include the design of target molecules, the targeted biological functions, and the considerations that led to Lipinski's rules of five to estimate the probability for success (Lipinski et al., 2001; Lipinski, 2004; Tice, 2001). It is not surprising that agrochemicals and their analogs can, independent of the molecular target sites, be repurposed for use as pharmaceuticals and vice versa (Delaney et al., 2006; Swanton et al., 2011).

Although there are several similarities in the development processes of agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals, there are substantial differences, too. One such difference is the cost of production. Contrary to the pharmaceutical industry, and because farm incomes vary greatly by country, the manufacturing cost is arguably the most critical factor for the final decision to launch a new agrochemical in a specific market. The use of fluorinated building blocks for the synthesis of agrochemically active ingredients results in a general increase in costs, which limits their use in agrochemicals, especially in developing countries (Labrada, 2003; Holm and Johnson, 2009; Chauhan and Mahajan, 2014). Given the difference in production/usage volume between pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals, the environmental impact of the latter is even more significant. In general, fluoro-containing agrochemicals decompose in water and soil into inorganic fluorides, which might negatively affect plant growth and result in reduced crop yields (Arnesen, 1997; Mackowiak et al., 2003). An even more pressing concern is the potential contamination of water and soil with perfluoroalkylated compounds, which are relatively robust and thus resistant to decomposition owing to the strong carbon-fluorine (C-F) bond (O’ Hagan, 2008). Consequently, they remain as pollutants for longer in water and soil and accumulate in animals, where they are transformed into something toxic materials. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfate (PFOS) are examples of ubiquitous perfluoroalkylated chemicals, both of which pose a serious environmental threat (Lau, 2015; Cordner et al., 2019; Cousins et al., 2020; Herkert et al., 2020; Kwiatkowski et al., 2020).

According to our previous report, the percentage of organofluorine compounds to pharmaceuticals in the last three decades (1991–2019) is 18% (191 fluoro-pharmaceuticals/1072 all medicines, Figure 2A) (Inoue et al., 2020). We thus started our investigation using the database of the 18th edition of the Pesticide Manual in order to evaluate the contribution of fluorine-containing materials to agrochemicals (Turner, 2018). Among 1,261 pesticides in total (including organic and inorganic compounds, acids and their salts), we found 202 fluorine-containing pesticides, i.e., 16% of launched pesticides are fluorine-containing materials (Figure 2B, a full list of the names of all 1,261 pesticides with 202 fluorine-containing materials is given in Supplemental Information, see also Tables S1 and S2). The data are somewhat similar to the case of pharmaceuticals, although the comparison periods are different. This preliminary analysis prompted us to further investigate the contribution of organofluorine compounds to agrochemicals in order to potentially identify new areas of chemical space that may potentially yield advanced agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals.

Figure 2.

Contributions of Fluorine-Containing Compounds

(A) To pharmaceuticals (1991–2019).

(B) To agrochemicals (data based on the Pesticide Manual, 18th edition).

In this review, we analyze a database of agrochemicals focusing on the contribution of organofluorine compounds. Our database of agrochemicals is mainly based on Alan Wood's website, “Compendium of Pesticide Common Names” (Wood, 2020), "18th edition of the Pesticide Manual" (Turner, 2018), "Pesticide Properties Database (PPDB)" (Lewis and Tzilivakis, 2017), "Bio-Pesticides Database (BPDB)" (Lewis et al., 2016), "Ag Chem New Compound Review 2020, 38” (Bryant, 2020), "Pesticide Data Index by California's Department of Pesticide Regulation" (California Department of Pesticide Regulation, 2020), and our own search of patents. Agrochemicals examined in this review refer to pesticides, including insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, rodenticides, molluscicides, nematicides, and other related compounds. However, we do not examine fertilizers or soil conditioners. Including compounds withdrawn from the database, we have surveyed 424 fluoro-agrochemicals (300 compounds assigned with ISO common names and 44 compounds with non-ISO common names, 69 compounds with development codes and 11 experimental pesticides) (ISO: International Organization for Standardization). The full list of fluoro-agrochemicals (424 compounds) with their names, molecular weights, formulas, agrochemical types, mode of actions, log P, Clog P, and chemical structures are provided in the Supplemental Information (see also Table S3, and Figure S1). Our database of 424 fluoro-agrochemicals excludes salts if their parent acids are included (fluoroacetic acid versus sodium fluoroacetate, for example). Additionally, five agents of inorganic agrochemicals that contain fluorine atoms are briefly introduced. Our analyses of the agrochemical database cover the historical contributions of organofluorine compounds, the distribution of fluoro functional groups (chemotypes), a subject category, a classification based on the mode of action, the presence/absence of fluoro-functionalized heterocycles, and chirality. These aspects reveal a unique relationship between fluoro-organic compounds and agrochemicals. Although there are several articles that review fluorine-containing organic molecules in agrochemicals (Cartwright, 1994; Theodoridis, 2006; Fujiwara and O' Hagan, 2014; Jeschke, 2004; Haufe and Leroux, 2019; Pazenok and Leroux, 2020), to the best of our knowledge, our collection of 424 fluoro-agrochemicals with accompanying entries (5 inorganics) is the most comprehensive. The analysis of fluoro-agrochemical chemotypes is also a unique way to estimate the potential for success of a compound on the agrochemical market. The fundamental frequency and rarity with which fluoro-agrochemicals occur is also briefly compared with those of fluoro-pharmaceuticals.

Analyses of Agrochemicals that Have Been Assigned a New ISO Common Name in over the Past Two Decades

As shown in the pie and bar charts in Figures 3A and 3B, we first analyzed the active ingredients of the agrochemicals that have been assigned new ISO common names over the past two decades (1998–2020 (June)), via a comparison of fluoro-agrochemicals and non-fluoro-agrochemicals. The names and year that it was assigned for all the agrochemicals investigated in Figure 3 are shown in Table S4. During this period, 127 fluoro-agrochemicals were registered, which accounts for 53% of all active agrochemical ingredients (238 compounds) (Figure 3A). Despite the higher cost of fluorine-containing synthetic building blocks relative to their non-fluorinated counterparts, fluoro-agrochemicals have maintained a position as a strong competitor to non-fluorinated pesticides. It is indeed striking that every year more than 50% of compounds with new ISO common names are fluoro-organic compounds (Figure 3B). The data for the last 5 years (2016–2020 (June)) shows the significant impact that fluoro-agrochemicals have had. A total of 28 fluoro-agrochemicals have gained ISO common names, and their structures are shown in Figure 4. Over this 5-year period, their contribution to the number of newly assigned ISO common names is extraordinarily high, reaching an average of 67% over this period (fluoro/non-fluoro = 28/14; 2016: 57% (4/3); 2017: 68% (13/6); 2018: 43% (3/4); 2019: 100% (1/0); 2020: 88% (7/1)) (Figure 3B). Significantly, these results suggest that biological efficacy is becoming more important than the disadvantages associated with the cost of producing fluorinated compounds. This shift could be related to progress in the synthetic methodology used to obtain organofluorine compounds (Shibata, 2016; Wang et al., 2014; Ojima, 2009), since cost-friendly synthetic tools for fluorination and trifluoromethylation have been a focus over the last 20 years or so.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of Fluoro/Non-fluoro-Agrochemicals Assigned New ISO Common Names (1998–2020 (June))

The list of all agrochemicals (238 compounds) including the fluoro-agrochemicals (127 compounds) is provided in Table S4.

(A) Pie chart.

(B) Bar chart depending on the year.

Figure 4.

The 28 Fluoro-Agrochemicals Assigned New ISO Common Names in the last Five Years (2016-2020 (June))

As the bar chart in Figure 5 shows, we next classified all 238 agrochemicals (1998–2020 June) into nine categories: fungicides (78 [38 + 40] compounds), herbicides (70 [35 + 35]), insecticides (60 [42 + 18]), acaricides (13 [10 + 3]), nematicides (7 [4 + 3]), plant growth regulators (4), herbicide safeners (3), rodenticides (2), and others (7 [5 + 2]). A total of 244 entries were thus generated owing to compounds appearing in either two (four compounds) or three (one compound) of the categories; for details, see Table S4. The first five major categories (fungicides, herbicides, insecticides, acaricides, and nematicides) were further subdivided into fluorinated versus non-fluorinated compounds to estimate the individual contribution of organofluorine compounds to each category. We found that, in the insecticide and acaricide categories, the contributions of fluorinated compounds are extraordinarily high (70% and 77%, respectively). In the other three main categories they make up ∼50% of the compounds (fungicides: 49%; herbicides: 50%; nematicides: 57%). This analysis suggests that the choice of organofluorine compounds for new insecticide or acaricide candidates is statistically highly advantageous and may help ensure success.

Figure 5.

Classification of Agrochemicals with New ISO Common Names (238 Compounds, 1998–2020 (June)) into Nine Categories: Fungicides, Herbicides, Insecticides, Acaricides, Nematicides, Plant Growth Regulators, Herbicide Safeners, Rodenticides, and Others (244 Entries)

The names of all agrochemicals (238 compounds) with their agrochemical types is provided in Table S4.

Classification of Fluoro-Agrochemicals by Chemotype

Selecting small organic molecules to act as a ligand to target biomolecules such as enzymes, proteins, DNA, and carbohydrates on the surface or inside cells is crucial to successfully design new bioactive reagents. These ligands generally interact with biomolecules to form complexes, which establishes control over biological processes in, e.g., insects, plants, and bacteria. It is well known that the addition of fluorine atoms and fluorinated functional groups to active compounds can improve their binding by altering hydrogen-bonding interactions, ionic interactions, lipophilicity, and van der Waals forces (Ojima, 2009). The properties of the individual functional groups determine how they alter the binding interactions. Given the high number of fluoro-functional group chemotypes, such as fluoro (F), trifluoromethyl (CF3), and difluoromethyl (CF2H), we next analyzed the frequency with which each chemotype is found in fluoro-functionalized agrochemicals. First, the database of all fluoro-agrochemicals (424 compounds, see also Table S3 and Figure S1) was subdivided into 34 groups of fluoro-functional motifs such as aromatic fluorides (Ar-F), heteroaromatic fluorides (Het-F), vinyl-fluorides (C=CRF), trifluoromethyl-substituted aromatic groups (Ar-CF3), trifluoromethyl-substituted heteroaromatic groups (Het-CF3), vinyl-trifluoromethyl groups (C=CRCF3), difluoromethyl-substituted heteroaromatic groups (Het-CF2H), perfluoroalkyl-substituted aromatic groups (Ar-Rf), alkyl-fluorides (alkyl-F), and trifluoromethyl-alkanes (alkyl-CF3), which expanded the database to 541 entries owing to duplicates (95 compounds), triplicates (8 compounds), and quadruplicate (2 compounds) (Figure 6). The largest subdivision of fluoro-agrochemicals is the group that contains an "Ar-F" moiety (156 entries, 29%), followed by the groups that contain an "Ar-CF3" moiety (117 entries, 22%), a "Het-(Csp2)-CF3" moiety (69 entries, 13%), or an "alkyl-CF3" moiety (26 entries, 5%). Fluoro-functionalized aromatic compounds contribute greatly to these groups. Thus, the preparation of aromatic compounds with F and CF3 groups, rather than fluoro-functionalized aliphatic compounds, is more likely to furnish successful agrochemical candidates. This analysis is somewhat different to the database of fluoro-pharmaceuticals (Inoue et al., 2020), where the contribution of fluoro-functionalized aliphatic compounds with F and CF3 groups are as abundant as the fluoro-functionalized aromatics. Fluoro-functionalized-heteroaromatic (Rf-Csp2) compounds (Het-CF3, Het-CF2X, Het-F, Het-CFXY; 107 entries, 20%) and fluoro-functionalized compounds that possess heteroatoms (X-Rf, 70 entries; X = O, S, SO2, N; 13%) are also found in fluoro-agrochemicals. This analysis suggests that, as their corresponding synthetic chemistry progresses, heterocycles (Nenajdenko, 2014) and heteroatom-conjugated fluoro-functional groups (Xu et al., 2015; Besset et al., 2016; Tlili et al., 2016; Manteau et al., 2010; Leroux et al., 2005, 2008; Savoie and Welch, 2015; Das et al., 2017) have the potential to be successful candidates for agrochemicals because they still account for relatively few of the compounds in the database.

Figure 6.

Distribution of Chemotypes of Fluoro-Agrochemicals (424 Compounds, 541 Entries, 33 Groups)

We reorganized the pie chart and carried out a classification of fluoro-agrochemicals into another seven groups focusing on the numbers of fluorine atoms present per functional group as in, e.g., mono-fluorinated groups (Csp2-F, Csp3-F), trifluoromethyl groups (Csp2-CF3, Csp3-CF3), difluoromethyl groups (Csp2-CF2X, Csp3-CF2X), and carbonyl-Rf groups (C(=O)-CFxRy) (Figure 7). The reorganized pie chart (Figure 7) indicates that the compounds that contain C-CF3 moieties account for 42% (228 entries) of all fluorine-containing compounds. Compounds that contain monofluoro moieties such as Csp2-F and Csp3-F cover 35% (191 entries) of all compounds in the database. The tendency for there to be more compounds that contain C-CF3 groups than compounds that contain C-F groups should be noted since it stands in sharp contrast to that found in fluoro-pharmaceuticals. A recent analysis of a pharmaceutical database revealed that the monofluoro C-F chemotype is the major group found in fluoro-pharmaceuticals (67%), whereas drugs with trifluoromethyl groups account for ∼20% (Inoue et al., 2020). This comparison reveals that the CF3 moiety has particular advantages for agrochemicals, whereas the C-F moiety has advantages for pharmaceuticals.

Figure 7.

Chemotype Distribution of Fluoro-Agrochemicals Focusing on the Number of Fluorine Atoms Present Per Functional Group (424 Compounds, 541 Entries, 8 Groups)

Classification of Fluoro-Agrochemicals by Agrochemical Type

As the pie chart in Figure 8A shows, we next classified all 424 agrochemicals into 14 agrochemical types (expanding to 477 entries after taking duplicates into account) including herbicides (192 compounds), insecticides (121), fungicides (80), acaricides (45), nematicides (8), plant growth regulators (7), and rodenticides (7) (see also Table S3 for the full list). The fluoro-agrochemicals were found to be distributed relatively evenly among all the groups, whereby each group was sized proportionately in relation to the size of their respective sectors (see also Figure S2) (Turner, 2018). However, we were surprised to see the results of the analysis of the agrochemical-type distribution obtained by focusing on the number of fluorine atoms per molecule. When we focused on the compounds with more than six fluorine atoms in their structures (57 compounds, 72 entries), the clear majority of fluoro-agrochemicals (total 75%) are insecticides (53%) and acaricides (22%) (Figure 8B, see also Table S5). This result can be rationalized in terms of the lipophilicity of a compound, which is strongly related to its ability to penetrate biological membranes in vivo (Bégué and Bonnet-Delpon, 2008; Purser et al., 2008). Moreover, a highly lipophilic compound is crucial, particularly in the case of insecticides, for the translocation via the surface of the insects. This concept can be understood as “contact activity.” Higher lipophilicity enables agrochemicals to be taken up more efficiently across lipophilic waxy, cuticular, and chitin surface barriers (Lewis, 1980). It also facilitates extracellular movement within biological cell membranes and cell walls. In addition, higher lipophilicity renders herbicides more resistant to being washed out by rain. The lipophilicity of fluorinated molecules usually increases with increasing number of fluorine atoms, resulting in advantages for insecticides against rasping insects, such as mites, which feed on surface cells. More interestingly, molecules with an even higher fluorine content such as sulfluramid, flursulamid, and LPOS, are considered “fluorous” (Gladysz et al., 2004; Zhang, 2009; Zhang and Cai, 2008), i.e., they are lipo- and hydrophobic. Even though such fluorous properties might be advantageous for insecticides and acaricides, the use of fluorous organic chemicals remains controversial (Lau, 2015; Cordner et al., 2019; Gladysz et al., 2004; Zhang, 2009; Zhang and Cai, 2008; Cousins et al., 2020; Herkert et al., 2020; Kwiatkowski et al., 2020). The unique chemical structures of fluoro-agrochemicals with more than eight fluorine atoms are shown in Figure 9 (18 examples, 15 are insecticides/acaricides, 2 are herbicides, and 1 is fungicide).

Figure 8.

Classification of Fluoro-Agrochemicals by Agrochemical Type

(A) For all fluoro-agrochemicals (424 compounds, 477 entries).

(B) For fluoro-agrochemicals with more than six fluorine atoms in their structures (57 compounds, 72 entries).

Figure 9.

Examples of Fluoro-Agrochemicals with More than Eight Fluorine Atoms in Their Structures

Distribution of the Fluoro-Agrochemicals by Molecular Weights and Log P (Lipinski's “Rule of Five”)

In the pharmaceutical industry, one of the most straightforward criteria used to identify possible lead compounds for clinical therapeutics is a molecular mass of <500 Da and an octanol-water partition coefficient log P of <5. This is known as Lipinski's rule of five (Lipinski et al., 2001; Tice, 2001; Lipinski, 2004), and this rule has also been discussed in relation to agrochemicals. Therefore, we next examined the molecular mass distribution of the fluoro-agrochemicals within the selected agrochemical-type categories (e.g., herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, and acaricides) (Figure 10A). In the case of herbicides and fungicides, the 300- to 400-Da range is the most populated bin for both (109 herbicides; 44 fungicides). This result is in good agreement with Lipinski's rule of five. On the other hand, the most populated bin for insecticides and acaricides is the 400- to 500-Da range (44 insecticides; 17 acaricides). It should be noted that 38 insecticides and 16 acaricides are found in the bin >500 Da, i.e., outside the range of Lipinski's rule of five. Molecular weights >500 Da are significant as this often results in problems related to lower solubility and inferior membrane penetration. As discussed in the previous section, these factors are highly correlated to the higher fluorine content found in insecticides and acaricides.

Figure 10.

Distribution of Fluoro-Agrochemicals According to the “Rule of Five”

(A) Molecular weight.

(B) log P (calculated).

(C) Clog P (calculated). Details are provided in Table S3.

We further analyzed the database focusing on their calculated log P and Clog P values (Mannhold et al., 2009) (Figures 10B and 10C, both calculated log P and Clog P values were obtained by ChemDraw professional [version 19.1], whereas some of them were estimated by ACD/Log P). It should be emphasized again that herbicides and fungicides, the 3 to 5 range of both log P and Clog P is the most populated bin for both (for log P, 98 [54 + 44] herbicides and 53 [25 + 28] fungicides; for Clog P, 93 [49 + 44] herbicides and 46 [30 + 16] fungicides). On the other hand, the most populated bin for insecticides and acaricides is more than 5 (for log P, 76 [34 + 42] insecticides and 31 [14 + 17] acaricides for Clog P, 75 [30 + 45] insecticides and 29 [9 + 20] acaricides). It should be exciting to know that the numbers of drugs for both insecticides and acaricides are steadily increased with the increasing log P and Clog P, and more than 6 is the highest populated bin for both. These results strongly support the analyses mentioned in Figures 8B, 10B, and 10C that high lipophilicity of compounds is in advantages for insecticides feeding on surface cells. Thus, compounds that fall outside of Lipinski's rule should be considered for insecticides and acaricides. A higher level of calculation (Mannhold et al., 2009) and the experimental data of log P values of all agrochemicals should be effective for further understanding of these relationships. Full analyses of all agrochemical-type categories are available in the Supplemental Information (see also Figure S3).

Classification of Fluoro-Agrochemicals by Their Modes of Action

The phenomenon of agrochemical resistance against weeds, insects, acaricides, and various other parasites is one of the most significant problems in agrochemicals (Clark and Yamaguchi, 2002). This issue is strongly correlated to the excessive use of these chemicals and therefore necessitates continuous further research into the development of new, more effective agrochemicals. Probing the mode of action of pesticides with their target proteins represents a general strategy for effective resistance management. Even for pesticides with different chemical structures but having the same mode of action, the simultaneous use of multiple pesticides poses a significant risk for the generation of pesticide resistance. Thus, a global classification system for pesticides has been established for herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides in order to provide guidelines to prolong the effectiveness of pesticides and minimize the risk of resistance related to susceptibility. These classifications follow the recommendations suggested by the global Herbicide Resistance Action Committee (HRAC) for herbicides (HRAC classification) (Herbicide Resistance Action Committee, 2020), the Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC) for insecticides (Insecticide Resistance Action Committee, 2020), and the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) for fungicides (Fungicide Resistance Action Committee, 2020). Therefore, we classified the fluoro-agrochemicals based according to the rules of the HRAC, IRAC, and FRAC. Details of the analyses are shown in Figure 11 (herbicides, see also Table S6 for details), Figure 12 (insecticides, see also Table S7 for details), and Figure 13 (fungicides, see also Table S8 for details). As shown in these figures, all the classifications show clear biases toward particular modes of action. The HRAC mode of action classification of herbicides has 22 groups (group Z and "unknown" were omitted). Fluorinated herbicides (167 compounds) are found in 14 categories, whereby the four most substantial categories are category E (59 compounds), A (23 compounds), B (23 compounds), F1 (14 compounds), and K1 (11 compounds). Fluorinated insecticides (102 compounds) are categorized into 17 groups of a possible 28 (code UN and unknown were omitted). The most significant contributions are code 3 (33 compounds), code 15 (14 compounds), and code 2 (9 compounds), whereas no contributions were identified for codes 6, 7, 11, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 23, and 24. The FRAC classification for fluorinated fungicides (61 compounds) can be divided into 12 categories (Code U and "unknown mode of action" were omitted), and the largest categories are code C (31 compounds) and code G (13 compounds). In contrast, no compounds were located in categories with codes A and D. These three analyses suggest that the vacant categories should be targeted for the next generation of fluorinated pesticides to prevent or delay the evolution of resistance.

Figure 11.

HRAC Classification for Fluoro-Herbicides, including Herbicide Safeners and Plant-Growth Regulators (167 Compounds Selected)

A: Inhibition of acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACCase); B: Inhibition of acetolactate synthase ALS (acetohydroxyacid synthase AHAS); C1,2,3: Inhibition of photosynthesis at photosystem II; D: Photosystem-I-electron diversion; E: Inhibition of protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPO); F1: Inhibition of the phytoene desaturase (PDS); F2: Inhibition of 4-hydroxyphenyl-pyruvatedioxygenase (4-HPPD); F3: Inhibition of carotenoid biosynthesis (unknown target); F4: Inhibition of 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DOXP synthase); G: Inhibition of EPSP synthase; H: Inhibition of glutamine synthetase; I: Inhibition of DHP (dihydropteroate) synthase; K1: Inhibition of microtubule assembly; K2: Inhibition of mitosis/microtubule organization: Inhibition of VLCFAs (inhibition of cell division); L: Inhibition of cell wall (cellulose) synthesis; M: Uncoupling (membrane disruption); (N): Inhibition of lipid synthesis—not ACCase inhibition; O: Action like indole acetic acid (synthetic auxins): P; Inhibition of auxin transport.

Figure 12.

IRAC Classification for Fluoro-Insecticides, including Acaricides, and Molluscicides (102 Compounds Selected)

Code 1: Acetylcholine esterase inhibitors (Nerve action); Code 2: GABA-gated chloride channel antagonists (Nerve action); Code 3: Sodium channel modulators (Nerve action); Code 4: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists (Nerve action); Code 5: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists (Nerve action) (Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor allosteric activators); Code 6: Chloride channel activators (Nerve and muscle action); Code 7: Juvenile hormone mimics (Growth regulation); Code 8: Miscellaneous non-specific (multi-site) inhibitors; Code 9: Selective Homopteran feeding blockers (Nerve action); Code 10: Mite growth inhibitors (Acaricides); Code 11: Microbial disrupters of insect midgut membranes (includes transgenic crops expressing Bacillus thuringiensis toxins); Code 12: Inhibitors of mitochondrial ATP synthase (energy metabolism); Code 13: Uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation via disruption of the proton gradient (energy metabolism); Code 14: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel blockers (nerve action); Code 15: Inhibitors of chitin biosynthesis, type 0, Lepidopteran (growth regulation); Code 16: Inhibitors of chitin biosynthesis, type 1, Homopteran (growth regulation); Code 17: Molting disruptor, Dipteran (growth regulation); Code 18: Ecdysone receptor agonists (growth regulation); Code 19: Octopamine agonists (nerve action); Code 20: Mitochondrial complex III electron transport inhibitors (coupling site II) (energy metabolism); Code 21: Mitochondrial complex I electron transport inhibitors (energy metabolism); Code 22: Voltage-dependent sodium channel blocker (nerve action); Code 23: Inhibitors of acetyl CoA carboxylase (lipid synthesis, growth regulation); Code 24: Mitochondrial complex IV electron transport inhibitors (energy metabolism); Code 25: Mitochondrial complex II electron transport inhibitors (energy metabolism); Code 28: Ryanodine receptor modulators (nerve and muscle action) (Ryanodine receptor [RyR] calcium channel disruptor); Code 29: Chordotonal Organ Modulators—undefined target site; Code 30: GABA-gated chloride channel allosteric modulators (nerve action).

Figure 13.

FRAC Classification for Fluoro-Fungicides (61 Compounds Selected)

A: Nucleic acids metabolism; B: Cytoskeleton and motor proteins; C: Respiration; D; Amino acids and protein synthesis; E: Signal transduction; F: Lipid synthesis or transport/membrane integrity or function; G: Sterol biosynthesis in membranes; H: Glucan synthesis; I: Melanin synthesis in cell wall; P: Host plant defense induction; M: Chemicals with multi-site activity; Others: Biologicals with multiple modes of action

Fluoro-Agrochemicals that Contain Heterocycles

Heterocycles are extremely important scaffolds for the design of agrochemicals (Lamberth and Dinges, 2012). An estimated >70% of launched agrochemicals contain at least one heterocycle, in particular those heterocycles that contain nitrogen. For several reasons, the selection of the correct heterocyclic compound is a reliable method for the lead optimization of agrochemicals. First, the heterocyclic scaffolds themselves are potential pharmacophores with biological activity. Second, based on the balance of their hydrophilicity, lipophilicity and pKa values, heterocycles are suitable for fine-tuning the physicochemical properties of lead compounds. This improves their penetration, uptake, and bioavailability. Third, the heterocyclic moieties can be used as bioisosteres of carbon aromatics to alter their physicochemical properties and metabolism without significant structural alteration of the lead compound. From our database of 424 compounds, we identified those fluoro-agrochemicals that contain at least one heterocycle (Hong, 2009). Contrary to our expectations, only 61% of the fluoro-agrochemicals (259 compounds, see also Table S9 for details) contain heterocyclic moieties, whereas heterocycles-free fluoro-agrochemicals account for an impressive 165 compounds (39%) (Figure 14A). These results suggest that fluoro-organic compounds do not always require heterocyclic skeletons to be successful agrochemicals and that the presence of fluorine and heterocyclic moieties in agrochemicals independently alters the physicochemical properties of the parent molecules. The 259 fluoro-agrochemicals that contain heterocycles can be further divided into two categories in which the fluorine or fluoro-functional groups are either directly attached to the heterocyclic core or not (Figure 14B). A total of 134 compounds have directly fluoro-functionalized heterocyclic cores, whereas 125 fluoro-agrochemicals have fluorine-free heterocyclic moieties. These results suggest that the fluorine and heterocycles form a good partnership for design of agrochemical structures (Figure 14A), but fluorine is not always necessary directly attached to the heterocyclic skeletons (Figure 14B).

Figure 14.

Fluoro-Agrochemicals with/without Heterocycles

(A) Distribution of fluoro-agrochemicals with (259 compounds) or without (165) heterocycles.

(B) Distribution of heterocyclic moieties with (134 compounds) or without (125) fluoro-functional groups.

The 134 compounds with fluoro-functionalized heterocycles were further divided into two categories (Het(Csp2)-Rf and Het(Csp3)-Rf), with 26 heterocyclic skeletons, i.e., six-membered rings (e.g., pyridines and pyrimidines) and five-membered rings (e.g., pyrroles and pyrazoles); the results are shown in the 3D-bar chart in Figure 15. A significant bias was found for pyridine (43 compounds) and pyrazole (35). Moreover, CF3-functionalized pyridine (31 compounds) is the most populated category, followed by CF2X-functionalized pyrazole (14) rather than CF3-functionalized pyrazole. As can be seen in Figure 15, many fields are vacant, especially in the categories of Het(Csp3)-Rf, which indicates a strong requirement for new synthetic tools in fluorine chemistry targeted at fluoro-functionalized heterocycles (Muzalevskiy et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2012).

Figure 15.

Diversity of Fluoro-Functional Groups Directly Attached to the Heterocyclic Cores of Fluoro-Agrochemicals

Chirality in Fluoro-Agrochemicals

The evolution of molecular complexity has become an essential factor in drug design in order to widen the chemical space and this is now well-established in medicinal chemistry. Natural products such as alkaloids, steroids, and sugars are excellent examples of molecules with distinct chemical spaces, and the inherent chirality of many of these molecules results in sp3-rich compounds and a widening of chemical space relative to anthropogenic compounds (Oscar and Medina-Franco, 2017). Currently, more than 50% of commercially available pharmaceuticals contain a fragment with a chiral center (Sanganyado et al., 2017). Interestingly, the same situation has become more common for agrochemicals in recent years. Presently, about 30% of agrochemicals are chiral compounds, including racemic mixtures (Jeschke, 2018), and the number of chiral agrochemicals has increased in recent years. One recent example is fluralaner (Bravecto), developed by Nissan Chemical Industries ltd., which is a systemic insecticide and acaricide used to inhibit GABA-gated and l-glutamate-gated chloride channels in the nervous system of insects (Figure 16A) (Weber and Selzer, 2016). Fluralaner contains a quaternary stereogenic carbon center directly connected to a CF3 group. Although the (S)-enantiomer of fluralaner is more potent than the (R)-isomer, fluralaner was launched as a racemic mixture due to production costs. In 2010, we reported the use of asymmetric organo-catalysis for the enantioselective synthesis of trifluoromethylated isoxazolines and related compounds; this chemistry is useful for the synthesis of the (S)-enantiomer of fluralaner (Figure 16B) (Matoba et al., 2010; Kawai and Shibata, 2014). Nowadays, several fluralaner derivatives, including their enantiomers, have been assigned ISO common names by different companies (Weber and Selzer, 2016).

Figure 16.

Fluralaner (Bravecto)

(A) Structure of fluralaner.

(B) Asymmetric synthesis of (S)-fluralaner using asymmetric organo-catalysis.

With this in mind, we next ordered the database according to the proportion of fluoro-agrochemicals with chiral fragments in their structures. The number of fluoro-agrochemicals with an asymmetric carbon center (144 compounds including 41 chiral compounds and 103 racemic compounds) accounts for 34% (10% + 24%) of all the fluoro-agrochemicals (Figure 17A, see also Table S9). However, the number of fluoro-agrochemicals with fluorine or fluoro-functional groups directly connected to a stereogenic carbon center (14 compounds; 3 herbicides; 11 insecticides), which includes racemic compounds, is extremely low (Figure 17B). In the case of fluoro-pharmaceuticals, 62 compounds (18% for all 340 fluoro-pharmaceuticals) are in this category (Inoue et al., 2020). Although these 14 compounds make up 3% of all fluoro-agrochemicals, most of these are derivatives of fluralaner (6 compounds) or benzoylurea (lufenuron, novaluron, and noviflumuron). Thus, the net percentage of all fluoro-agrochemicals with a stereogenic center is only 1.4% (6 compounds) (Figure 18). This analysis suggests that existing synthetic methods may not be sufficient for the effective preparation of chiral fluorinated agrochemicals (Shibata et al., 2007, 2008; Zhu et al., 2018). Nevertheless, asymmetric synthetic technology has rapidly expanded in recent decades to include fluoro-organic molecules. Thus, as is now common in the pharmaceutical industry, fluoro-agrochemicals with stereogenic carbon center(s) will most likely receive increased attention in the near future (Jeschke, 2018).

Figure 17.

Fluoro-Agrochemicals with/without a Stereogenic Carbon Center

(A) Distribution of fluoro-agrochemicals with (41 chiral compounds, 103 racemic compounds) or without (280) a stereogenic carbon center.

(B) Distribution of fluoro-agrochemicals with fluorine or fluoro-functional groups directly connected to a stereogenic carbon center, which includes racemic compounds (14 compounds) and others (410 compounds).

Figure 18.

Fluoro-Agrochemicals Having a Fluoro-Functionalized Stereogenic Carbon Center

Inorganic Fluorine-Containing Agrochemicals

Although we excluded the five fluorine-containing inorganic agrochemicals shown in Figure 19 (1 herbicide; 4 insecticides) from the previous analyses, their names, structures, and agrochemical types are summarized here for the sake of completion.

Figure 19.

Fluorine-Containing Inorganic Agrochemicals: Hexaflurate, Sodium Fluoride, Cryolite, Sodium Silicofluoride, and Barium Hexafluorosilicate

Environmental Risk of Fluoro-Agrochemicals

As we have shown, fluoro-agrochemicals have become globally indispensable for maintaining crop production and protecting public health from parasitically transmitted (e.g., mosquitos) infectious diseases, which has resulted in a dramatic increase in their use. The ubiquitous use of fluoro-agrochemicals poses severe risks to animals and the environment, as exemplified by the environmentally persistent DDT (cf. the Silent Spring in the 1960s; Figure 1A) (Primbs et al., 2008; Bossi et al., 2016; McGoldrick and Murphy, 2016; Takazawa et al., 2016). Given that several pesticides based on organic chlorines (Sparling, 2016) serve as notorious historic examples, the environmental impact of fluoro-agrochemicals should be discussed in depth, especially with respect to their potential bio-accumulation (Murphy et al., 2011). Organofluorine compounds are generally more stable than, e.g., their organochlorine derivatives owing to the exceptional strength of the C-F bond, which leads to an extraordinary robustness of fluoro-agrochemicals, reflected in their resistance against enzymatic, chemical, and environmental degradation. This robustness is, on one hand, advantageous for the intended purpose. On the other hand, the exceptional environmental stability of fluoro-agrochemicals means that they can be expected to pollute the soil, the atmosphere, and water, ultimately leading to bio-accumulation in diverse organisms via the food cycle. Such undesired, long-term environmental effects of agrochemicals are difficult to predict and thus remain a major concern for prolonged periods after their commercial launch (Murphy, 2010). A recent representative example of such a case is trifluralin (Figure 1C), which was first synthesized in 1961 and commercially launched in 1963. Trifluralin represents essentially the first synthetic fluoro-agrochemical, notwithstanding that the rodenticide sodium fluoroacetate was first reported in 1936. Although trifluralin is relatively persistent, it is gradually degraded in soil by microorganisms with a degradation half-life of less than 1 year (US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 1996; Ribas et al., 1996; Gebel et al., 1997; Waite et al., 2004; Bouvier et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2008; Triantafyllidis et al., 2010). Nevertheless, trifluralin can be detected in the Arctic environment owing to sufficiently high quantities that are globally used and the long-range atmospheric transport that most likely occurs (Marinov et al., 2013). Trifluralin, which had been a very prominent drug for half a century, was eventually banned in the European Union in 2008, owing to its toxicity to aquatic and human life (UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), 2007).

From an environmental risk-assessment perspective, special attention should be focused on the use of fluorous agrochemicals, as their extremely high stability can be expected to result in long environmental persistence (Giesy and Kannan, 2001; Piekarz et al., 2007). For example, sulfluramid, flursulamid, LPOS, and SIOC-I-013 (Figure 9) should be considered as fluorous agrochemicals on account of their linear per-fluoroalkyl structures. These are all insecticides that are used against invasive ants, red fire ants, and cockroaches (Lee and Yonker, 2003; Sunamura et al., 2011). LPOS, also known as Super-Arinosu-Korori, is a popular component of commercially available insecticides in Japan for the control of household pest ants. Despite their popularity, these insecticides have been strongly suspected of exhibiting environmental toxicity due to potential bio-accumulation caused by their perfluoroalkyl chains. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), i.e., perfluoroalkyl acids and sulfonates with alkyl chains that contain more than eight carbon atoms, are persistent and bio-accumulative substances that have been found anywhere around the world, including in the Atlantic and Arctic oceans (Benskin et al., 2012).

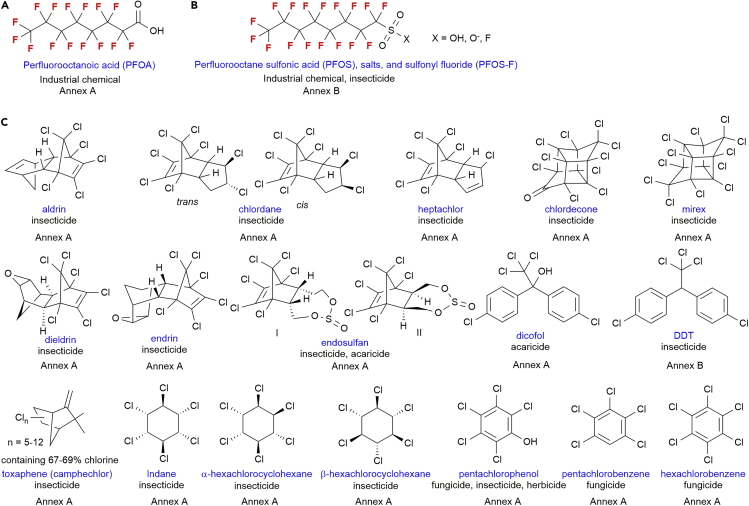

In response to increasing demands of environmental protection, the Stockholm Convention stated in 2004 to protect human health and the environment from persistent organic pollutants (POPs) (Stockholm Convention, 2020). Initially, twelve POPs were listed owing to their adverse environmental effects in Annexes A–C (A, Elimination; B, Restriction; C, Unintentional production). Since then, the number of POPs included have been expanded occasionally. Presently, 35 POPs are in the lists (26 POPs in Annex A; 2 POPs in Annex B; 7 POPs in Annex C, August 2020) (see also Table S11). In 2019, PFOA, its salts, and PFOA-related compounds have been included as POPs in Annex A (Figure 20A). PFOS, its salts, and perfluorooctane sulfonyl fluoride (PFOS-F) were included in Annex B (Restriction) in 2009 (Figure 20B). The insecticides LIPO, sulfluramid, and flursulamid are specifically exempt from Annex B for specific acceptable agricultural use. It seems thus strongly advisable to pay special attention to the usage of such POPs. Although insecticides such as EL-499-1 and EL-499-2 (Figure 9), which exhibit cyclic perfluoroalkyl structures, have not yet been targeted, their commercial/agricultural/industrial use should be closely watched for the very same reason. It should also be noted here that the Stockholm Convention contains currently 18 pesticides in Annexes A (17 POPs) and B (one POP); however, 17 of these POPs are organochlorine-based agrochemicals (Figure 20C), whereas there is only one organofluorine agrochemical, PFOS (Figure 20B). This might indicate that fluoro-agrochemicals are of lower environmental toxicity than organochlorine agrochemicals (Camenzuli et al., 2016; Shunthirasingham et al., 2016), but until this point is proven unequivocally, it seems prudent to closely monitor and/or regulate the use of fluorous agrochemicals.

Figure 20.

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) Stockholm Convention

Annex A: Parties must take measures to eliminate the production and use of the chemicals listed under Annex A. Annex B: Parties must take measures to restrict the production and use of the chemicals listed under Annex B in light of any applicable acceptable purposes and/or specific exemptions listed in the Annex. See the website of Stockholm Convention.

(A) PFOA.

(B) PFOSs. Fluorous agrochemicals such as LIPO, sulfluramid, and flursulamid belong to this group.

(C) All POP agrochemicals according to the Stockholm Convention (2020, August).

We finally analyzed the distributions of chemicals and their categories in the list of POPs Stockholm Convention (Figure 21, see also Table S11). First, 35 POPs were expanded into 38 entries, owing to the three duplications of categories, i.e., 18 pesticides, 13 industrial chemicals, and 7 unintentional productions. These results indicate that most POPs are pesticides; thus, pesticides' environmental risk should be considered substantially. We further divided each category into the chemical types. A total of 31 chlorinated-chemicals (17 + 7 + 7) are found, whereas the brominated chemicals (4) and fluoro-chemicals (1 + 2) are much less.

Figure 21.

The Distributions of Chemicals and Their Categories in the List of POPs Stockholm Convention

The 35 POPs are expanded to 38 entries owing to the 3 duplications. Pesticides: 18; industrial chemicals: 13; unintentional productions: 7. See the full list in Table S11.

These environmental effects lead to the need to explore more synthetic routes to access previously inaccessible fluorine and non-fluorine agrochemicals. Furthermore, emerging chemical pollutants are being identified, so chemists must balance efficacy, environmental impact, and human health.

Conclusions

We have analyzed the recent contributions of organofluorine molecules to the field of agrochemicals. Our analyses are mainly dominated by the data relating to launched fluoro-agrochemicals that had not been analyzed previously. Our collection of fluoro-agrochemicals contains 424 organofluorine compounds with a full list of their names and chemical structures. Although there are several reviews and books on fluoro-agrochemicals, these data are, to the best of our knowledge, the most extensive collection of fluoro-agrochemicals. Although we have not discussed in detail the biological aspects, in particular the mode of action at the molecular level, of these organofluorine pesticides, we have indicated the merits and advantages of organofluorine compounds as agrochemicals from the viewpoint of success in the agrochemical market. Moreover, we have conducted structural analyses of fluoro-agrochemicals focusing on the fluoro-functional groups, chemotypes, and number of fluorine atoms present in the structure, the heterocyclic skeleton, and chirality. These analyses revealed that the unique biases and trends toward fluoro-organic molecules depend on the agrochemical type and suggest some structural recommendations for agrochemical drug design in academia and industry. Interestingly, the fluoro-agrochemicals could be divided, from a fluorine-focused structural point of view, into two categories, i.e., "herbicides and fungicides" as well as "insecticides and acaricides." Fluorinated herbicides and fungicides have some similarities to fluoro-pharmaceuticals, whereas insecticides and acaricides are quite different. For example, fluorinated insecticides and acaricides do not follow Lipinski's rule of molecular weight or follow expected trends relating to lipophilicity. The significant preference for trifluoromethyl groups rather than mono-fluorinated moieties in the structures of agrochemicals is another way that fluoro-agrochemicals are different from fluoro-pharmaceuticals. Although our suggestions are far from comprehensive guidelines toward the design of organofluorine agrochemicals, we have been able to highlight some trends, metrics, and frontiers of fluoro-agrochemicals that may lead to the successful discovery of lead compounds for future crop protection.

Throughout this review, we have been impressed with the rapid progress of synthetic organofluorine chemistry over the last two decades. According to the Pesticide Manual (13th edition, BCPC, Alton, Hampshire, 2003), 16% of agrochemicals were fluorinated molecules at the time of publication. Our analysis of the period 1998–2020 revealed that this had risen to 53%, whereas the analysis of the latest 5 years indicates that 67% of agrochemicals are organofluorine compounds. This recent rise in the number of organofluorine compounds on the market is well supported by the significant progress that has been made in synthetic organofluorine chemistry. In particular, recent advances in fluorination and trifluoromethylation technology have resulted in a greater availability of cost-friendly fluorine-containing synthetic building blocks. As discussed in this review, there are many avenues yet to be explored in the field of fluoro-agrochemicals. For example, compounds that have unique fluorinated motifs such as fluoro-functionalized heteroaromatics, heteroatomic groups such as OCF3, SCF3, or SF5, should be examined further in the near future. Difluoromethyl group, CF2H is emerging more rapidly with respect to the CF3 group due to progress of synthetic methods. New synthetic methods will enable fluoro-organic compounds to meet the demand for agrochemicals that are safer and more ecologically viable.

Before closing this review, we should again stress the importance of the environmental risk assessment of fluoro-agrochemicals prior to their market introduction. Similar to conventional pesticides, the excessive use of agrochemicals can be expected to lead to the contamination of soil, water, and the atmosphere, rendering these poisonous to non-targeted organisms and causing the death of aquatic, terrestrial, and avian animals by bio-accumulation. Fluoro-agrochemicals, especially fluorous agrochemicals, such as LIPO, sulfluramid, and flursulamid, require particular attention owing to their exceptionally high stability that arises from their strong C-F bonds. Thus, the design of fluoro-agrochemicals should always include considerations regarding environmental persistence. We hope this review will become a helpful guide for scientists working and teaching in the field of both crop protection and infectious diseases.

Limitations of the Study

The environmental risk of fluoro-agrochemicals needs more analyses and discussions. The authors will review this topic again somewhere in the near future.

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Norio Shibata (nozshiba@nitech.ac.jp).

Materials Availability

This study did not use or generate any reagents.

Data and Code Availability

This published article includes all datasets generated or analyzed during this study.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Pesticide Science Society of Japan (N.S., E.T.) and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI grants JP 18H02553 (Kiban B, N.S.). We would like to thank Ube Industries, Ltd., Tosoh Finechem Corporation, Sumitomo Chemical Company, Limited, Nissan Chemical Corporation, and Kumiai Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. for their support. We also thank Dr. Munenori Inoue for helpful discussion for the preparation of the manuscript, Dr. James Turner (Editor, the Pesticide Manual), Professor Kathy Lewis (University of Hertfordshire, the PPDB database), Dr. Alan Wood (Website of Compendium of Pesticide Common Names), and Dr. Rob Bryant (Agranova, Ag Chem database) for useful communications concerning agrochemicals. We also thank Miss Mami Shibata for the discussion of Rachel Carson's book "Silent Spring".

Author Contributions

K.H. and N.S. conceived the concept of this study. Y.O., E.T., O.K., K.H., and N.S. collected and analyzed the data. K.H. and N.S. directed the project. Y.O., E.T., and N.S. prepared the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101467.

Contributor Information

Kenji Hirai, Email: k-hirai@sagami.or.jp.

Norio Shibata, Email: nozshiba@nitech.ac.jp.

Supplemental Information

The database excluded salts if the parent acids included. 1) code: development code; exp.: experimental pesticides.

144 compounds including 41 chiral compounds and 103 racemic compounds fluoro-agrochemicals with fluorine or fluoro-functional groups directly connected to a stereogenic carbon center (14 compounds; 3 herbicides; 11 insecticides).

Convention

The chemicals targeted by the Stockholm Convention are listed in the annexes of the convention text Annex A (Elimination); Annex B (Restriction); Annex C (Unintentional production).

References

- Ames B.N., Gold S.L. Environmental pollution, pesticides, and the prevention of cancer: misconceptions. FASEB J. 1997;11:1041–1052. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.13.9367339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen A.K.M. Availability of fluoride to plants grown in contaminated soils. Plant Soil. 1997;191:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Benskin J.P., Muir D.C.G., Scott B.F., Spencer C., De Silva A.O., Kylin H., Martin J.W., Morris A., Lohmann R., Tomy G. Perfluoroalkyl acids in the atlantic and Canadian Arctic oceans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:5815–5823. doi: 10.1021/es300578x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besset T., Jubault P., Pannecoucke X., Poisson T. New entries toward the synthesis of OCF3-containing molecules. Org. Chem. Front. 2016;3:1004–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya A., Barik S.R., Ganguly P. New pesticide molecules, formulation technology and uses: present status and future challenges. J. Plant Protect. Sci. 2009;1:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bossi R., Vorkamp K., Skov H. Concentrations of organochlorine pesticides, polybrominated diphenyl ethers and perfluorinated compounds in the atmosphere of North Greenland. Environ. Pollut. 2016;217:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier G., Blanchard O., Momas I., Seta N. Pesticide exposure of non-occupationally exposed subjects compared to some occupational exposure: a French pilot study. Sci. Total Environ. 2006;366:74–91. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant R. vol. 38. AGRANOVA; 2020. http://www.agranova.co.uk/ (Ag Chem New Compound Review). [Google Scholar]

- Bégué J.-P., Bonnet-Delpon D. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry of Fluorine. [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Pesticide Regulation The Department of Pesticide Regulation. 2020. https://www.cdpr.ca.gov/dprdatabase.htm

- Camenzuli L., Scheringer M., Hungerbühler K. Local organochlorine pesticide concentrations in soil put into a global perspective. Environ. Pollut. 2016;217:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson R. Houghton-Mifflin; 1962. Silent Spring. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright D. Recent developments in fluorine-containing agrochemicals. In: Banks R.E., Smart B.E., Tatlow J.C., editors. Organofluorine Chemistry. Springer; 1994. pp. 237–262. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan B.S., Mahajan G. Springer-Verlag New York; 2014. Recent Advances in Weed Management. [Google Scholar]

- Clark J.M., Yamaguchi I. American Chemical Society; 2002. Agrochemical Resistance: Extent, Mechanism, and Detection (ACS Symposium Series (No. 808)) [Google Scholar]

- Cordner A., de La Rosa V.Y., Schaider L.A., Rudel R.A., Richter L., Brown P. Guideline levels for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water: the role of scientific uncertainty, risk assessment decisions, and social factors. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019;29:157–171. doi: 10.1038/s41370-018-0099-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins I.T., DeWitt J.C., Glüge J., Goldenman G., Herzke D., Lohmann R., Miller M., Ng C.A., Scheringer M., Vierke L. Strategies for grouping per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to protect human and environmental health. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts. 2020;22:1444–1460. doi: 10.1039/d0em00147c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P., Tokunaga E., Shibata N. Recent advancements in the synthesis of pentafluorosulfanyl (SF5)-containing heteroaromatic compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017;58:4803–4815. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney J., Clarke E., Hughes D., Rice M. Modern agrochemical research: a missed opportunity for drug discovery? Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11:839–845. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorenzo M.E., Scott G.I., Ross P.E. Toxicity of pesticides to aquatic microorganisms: a review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2001;20:84–98. doi: 10.1897/1551-5028(2001)020<0084:toptam>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp J.B., Schmitzer P.R., Crouse G.D. Fifty years of herbicide research: comparing the discovery of trifluralin and halauxifen-methyl. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018;74:9–16. doi: 10.1002/ps.4657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T., O’ Hagan D. Successful fluorine-containing herbicide agrochemicals. J. Fluor. Chem. 2014;167:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fungicide Resistance Action Committee 2020. https://www.frac.info/

- Gebel T., Kevekordes S., Pav K., Edenharder R., Dunkelberg H. In vivo genotoxicity of selected herbicides in the mouse bone-marrow micronucleus test. Arch. Toxicol. 1997;71:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s002040050375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesy J.P., Kannan K. Global distribution of perfluorooctane sulfonate in wildlife. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001;35:1339–1342. doi: 10.1021/es001834k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladysz J.A., Curran D.P., Horváth I.T. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2004. Handbook of Fluorous Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Gunther F.A., Blinn R.C. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. II. Analogs. p,p'-DFDT and its degradation Products1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950;72:4282–4284. [Google Scholar]

- Haufe G., Leroux F.R. Elsevier; 2019. Fluorine in Life Sciences: Pharmaceuticals, Medicinal Diagnostics, and Agrochemicals. [Google Scholar]

- Herbicide Resistance Action Committee 2020. https://hracglobal.com/

- Herkert N.J., Merrill J., Peters C., Bollinger D., Zhang S., Hoffman K., Ferguson P.L., Knappe D.R.U., Stapleton H.M. Assessing the effectiveness of point-of-use residential drinking water filters for perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7:178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Holm F.A., Johnson E.N. The history of herbicide use for weed management on the prairies. Prairie Soils and Crops. 2009;2:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hong W. Agricultural products based on fluorinated heterocyclic compounds. In: Petrov V.A., editor. Fluorinated Heterocyclic Compounds: Synthesis, Chemistry, and Applications. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 399–418. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M., Sumii Y., Shibata N. Contribution of organofluorine compounds to pharmaceuticals. ACS Omega. 2020;5:10633–10640. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c00830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insecticide Resistance Action Committee 2020. https://irac-online.org/

- Ito T., Handa H. Another action of a thalidomide derivative. Nature. 2015;523:167–168. doi: 10.1038/nature14628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke P. The unique role of fluorine in the design of active ingredients for modern crop protection. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:570–589. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke P. Current status of chirality in agrochemicals. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018;74:2389–2404. doi: 10.1002/ps.5052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D., Park S.K., Beane-Freeman L., Lynch C.F., Knott C.E., Sandler D.P., Hoppin J.A., Dosemeci M., Coble J., Lubin J. Cancer incidence among pesticide applicators exposed to trifluralin in the Agricultural Health Study. Environ. Res. 2008;107:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai H., Shibata N. Asymmetric synthesis of agrochemically attractive trifluoromethylated dihydroazoles and related compounds under organocatalysis. Chem. Rec. 2014;14:1024–1040. doi: 10.1002/tcr.201402023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgore L.B. New German insecticides. Soap Sanit. Chem. 1945;21:138–139. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer W., Schirmer U., Jeschke P., Witschel M. vol. 1-3. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2012. (Modern Crop Protection Compounds). [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski C.F., Andrews D.Q., Birnbaum L.S., Bruton T.A., DeWitt J.C., Knappe D.R.U., Maffini M.V., Miller M.F., Pelch K.E., Reade A. Scientific basis for managing PFAS as a chemical class. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrada R. FAO; 2003. Weed Management for Developing Countries-Addendum 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberth C., Dinges J. The significance of heterocycles for pharmaceuticals and Agrochemicals∗. In: Lamberth C., Dinges J., editors. Bioactive Heterocyclic Compound Classes: Agrochemicals. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2012. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lau C. Perfluorinated compounds: an overview. In: DeWitt J.C., editor. Toxicological Effects of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. Humana Press; 2015. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.-Y., Yonker J.W. Laboratory and field evaluations of lithium perfluorooctane sulfonate baits against domiciliary and peridomestic cockroaches in penang, Malaysia. Med. Entomol. Zool. 2003;54:381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Leroux F.R., Manteau B., Vors J.-P., Pazenok S. Trifluoromethyl ethers – synthesis and properties of an unusual substituent. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2008;4:13. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.4.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroux F., Jeschke P., Schlosser M. α-Fluorinated ethers, thioethers, and Amines: anomerically biased species. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:827–856. doi: 10.1021/cr040075b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C.T. The penetration of cuticle by insecticides. In: Miller T.A., editor. Experimental Entomology Cuticle Techniques in Arthropods. Springer; 1980. pp. 367–400. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K.A., Tzilivakis J., Warner D.J., Green A. An international database for pesticide risk assessments and management. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2016;22:1050–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K., Tzilivakis J. Development of a data set of pesticide dissipation rates in/on various plant matrices for the pesticide properties database (PPDB) Data. 2017;2:28. [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004;1:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackowiak C.L., Grossl P.R., Bugbee B.G. Biogeochemistry of fluoride in a plant–solution system. J. Environ. Qual. 2003;32:2230–2237. doi: 10.2134/jeq2003.2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandavilli A. Health agency backs use of DDT against malaria. Nature. 2006;443:250–251. doi: 10.1038/443250b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannhold R., Poda G.I., Ostermann C., Tetko I.V. Calculation of molecular lipophilicity: state-of-the-art and comparison of log P methods on more than 96,000 compounds. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009;98:861–893. doi: 10.1002/jps.21494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manteau B., Pazenok S., Vors J.-P., Leroux F.R. New trends in the chemistry of α-fluorinated ethers, thioethers, amines and phosphines. J. Fluor. Chem. 2010;131:140–158. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand P.A. Synthetic agrochemicals: a necessary clarification about their use exposure and impact in crop protection. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26:17996–18000. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05368-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinov D., Pistocchi A., Trombetti M., Bidoglio G. Assessment of riverine load of contaminants to european seas under policy implementation scenarios: an example with 3 pilot substances. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2013;10:48–59. doi: 10.1002/ieam.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matoba K., Kawai H., Furukawa T., Kusuda A., Tokunaga E., Nakamura S., Shiro M., Shibata N. Enantioselective syntehsis of trifluoromethyl-substituted 2-isoxazolines: asymmetric hydroxylamine/enone cascade reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:5762–5766. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGoldrick D.J., Murphy E.W. Concentration and distribution of contaminants in lake trout and walleye from the Laurentian Great Lakes (2008–2012) Environ. Pollut. 2016;217:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf R.L. Some insecticidal properties of fluorine analogs of DDT. J. Econ. Entomol. 1948;41:416–421. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C.D. Biodegradation and biotransformation of organofluorine compounds. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010;32:351–359. doi: 10.1007/s10529-009-0174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M.B., Loi E.I.H., Kwok K.Y., Lam P.K.S. Ecotoxicology of organofluorous compounds. In: Horváth I.T., editor. Fluorous Chemistry. Springer; 2011. pp. 339–363. [Google Scholar]

- Muzalevskiy V., Shastin A., Balenkova E., Haufe G., Nenajdenko V. Synthesis of trifluoromethyl pyrroles and their benzo analogues. Synthesis. 2009;23:3905–3929. [Google Scholar]

- Nenajdenko V. vols. 1 & 2. Springer International Publishing; 2014. (Fluorine in Heterocyclic Chemistry). [Google Scholar]

- New York University Researchers rediscover fast-acting German insecticide lost in the aftermath of WWII. 2019. Phys.orghttps://phys.org/news/2019-10-rediscover-fast-acting-german-insecticide-lost.html

- Nobel Foundation . Elsevier; 1964. Nobel Lectures: Physiology or Medicine 1942−1962. [Google Scholar]

- Ojima I. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2009. Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology. [Google Scholar]

- Oscar M.-L., Medina-Franco J.L. The many roles of molecular complexity in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today. 2017;22:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’ Hagan D. Understanding organofluorine chemistry. An introduction to the C–F bond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:308–319. doi: 10.1039/b711844a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazenok S., Leroux F.R. Chapter 16: modern fluorine-containing agrochemicals. In: Ojima I., editor. Frontiers of Organofluorine Chemistry. World Scientific; 2020. pp. 695–732. [Google Scholar]

- Piekarz A.M., Primbs T., Field J.A., Barofsky D.F., Simonich S. Semivolatile fluorinated organic compounds in Asian and Western U.S. Air masses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:8248–8255. doi: 10.1021/es0713678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primbs T., Wilson G., Schmedding D., Higginbotham C., Simonich S.M. Influence of Asian and Western United States agricultural areas and fires on the atmospheric transport of pesticides in the Western United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:6519–6525. doi: 10.1021/es800511x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purser S., Moore P.R., Swallow S., Gouverneur V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:320–330. doi: 10.1039/b610213c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas G., Surrallés J., Carbonell E., Xamena N., Creus A., Marcos R. Genotoxic evaluation of the herbicide trifluralin on human lymphocytes exposed in vitro. Mutat. Res. 1996;371:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1218(96)90090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanganyado E., Lu Z., Fu Q., Schlenk D., Gan J. Chiral pharmaceuticals: a review on their environmental occurrence and fate processes. Water Res. 2017;124:527–542. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoie P.R., Welch J.T. Preparation and utility of organic pentafluorosulfanyl-containing compounds. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:1130–1190. doi: 10.1021/cr500336u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N. Development of shelf-stable reagents for fluoro-functionalization reactions. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2016;89:1307–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N., Ishimaru T., Nakamura S., Toru T. New approaches to enantioselective fluorination: cinchona alkaloids combinations and chiral ligands/metal complexes. J. Fluor. Chem. 2007;128:469–483. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N., Mizuta S., Kawai H. Recent advances in enantioselective trifluoromethylation reactions. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2008;19:2633–2644. [Google Scholar]

- Shunthirasingham C., Gawor A., Hung H., Brice K.A., Su K., Alexandrou N., Dryfhout-Clark H., Backus S., Sverko E., Shin C. Atmospheric concentrations and loadings of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in the Canadian Great Lakes Basin (GLB): spatial and temporal analysis (1992–2012) Environ. Pollut. 2016;217:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon C. Christoph Merian Verlag; 1999. DDT: Kulturgeschichte einer Chemischen Verbindung. [Google Scholar]

- Sparling D.W. Academic Press; 2016. Chapter 4 - Organochlorine Pesticides in Ecotoxicology Essentials; pp. 69–107. [Google Scholar]

- Stockholm Convention Stockholm convention. 2020. http://chm.pops.int/Home/tabid/2121/Default.aspx

- Sunamura E., Suzuki S., Nishisue K., Sakamoto H., Otsuka M., Utsumi Y., Mochizuki F., Fukumoto T., Ishikawa Y., Terayama M. Combined use of a synthetic trail pheromone and insecticidal bait provides effective control of an invasive ant. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011;67:1230–1236. doi: 10.1002/ps.2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanton C.J., Mashhadi H.R., Solomon K.R., Afifi M.M., Duke S.O. Similarities between the discovery and regulation of pharmaceuticals and pesticides: in support of a better understanding of the risks and benefits of each. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011;67:790–797. doi: 10.1002/ps.2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takazawa Y., Takasuga T., Doi K., Saito M., Shibata Y. Recent decline of DDTs among several organochlorine pesticides in background air in East Asia. Environ. Pollut. 2016;217:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoridis G. Chapter 4 fluorine-containing agrochemicals: an overview of recent developments. In: Tressaud A., editor. Fluorine and the Enviroment. Elsevier; 2006. pp. 121–175. [Google Scholar]

- Tice C.M. Selecting the right compounds for screening: does lipinski’s rule of 5 for pharmaceuticals apply to agrochemicals? Pest Manag. Sci. 2001;57:3–16. doi: 10.1002/1526-4998(200101)57:1<3::AID-PS269>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlili A., Toulgoat F., Billard T. Synthetic approaches to trifluoromethoxy-substituted compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:11726–11735. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga E., Yamamoto T., Ito E., Shibata N. Understanding the thalidomide chirality in biological processes by the self-disproportionation of enantiomers. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:17131. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35457-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantafyllidis V., Manos S., Hela D., Manos G., Konstantinou I. Persistence of trifluralin in soil of oilseed rape fields in Western Greece. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2010;90:344–356. [Google Scholar]

- Turner J.A. 18th Edition. BCPC; 2018. The Pesticide Manual. [Google Scholar]

- UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) UNECE Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution. 2007. Trifluralin risk profile; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) Reregistration Eligibility Decision for Trifluralin. 1996. http://www.epa.gov/oppsrrd1/reregistration/REDs/0179.pdf

- Vaz S., Jr. Springer International Publishing; 2019. Sustainable Agrochemistry - A Compendium of Technologies. [Google Scholar]

- Waite D.T., Cessna A.J., Grover R., Kerr L.A., Snihura A.D. Environmental concentrations of agricultural herbicides in Saskatchewan, Canada: bromoxynil, dicamba, diclofop, MCPA, and trifluralin. J. Environ. Qual. 2004;33:1616–1628. doi: 10.2134/jeq2004.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Sánchez-Roselló M., Aceña J.L., Pozo C.d., Sorochinsky A.E., Fustero S., Soloshonok V.A., Liu H. Fluorine in pharmaceutical industry: fluorine-containing drugs introduced to the market in the last decade (2001–2011) Chem. Rev. 2014;114:2432–2506. doi: 10.1021/cr4002879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T., Selzer P.M. Isoxazolines: a novel chemotype highly effective on ectoparasites. ChemMedChem. 2016;11:270–276. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201500516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witschel M., Rottmann M., Kaiser M., Brun R. Agrochemicals against malaria, sleeping sickness, leishmaniasis and Chagas disease. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012;6:e1805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A. Compendium of Pesticide Common Names. 2020. http://www.alanwood.net/pesticides/