VLN1, required for bundling actin filaments in root hair growth and transcriptionally regulated by GL2, negatively regulates osmotic stress-induced root hair growth.

Abstract

Actin binding proteins and transcription factors are essential in regulating plant root hair growth in response to various environmental stresses; however, the interaction between these two factors in regulating root hair growth remains poorly understood. Apical and subapical thick actin bundles are necessary for terminating rapid elongation of root hair cells. Here, we show that Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) actin-bundling protein Villin1 (VLN1) decorates filaments in shank, subapical, and apical hairs. vln1 mutants displayed significantly longer hairs with longer hair growing time and defects in the thick actin bundles and bundling activities in the subapical and apical regions, whereas seedlings overexpressing VLN1 showed different results. Genetic analysis showed that the transcription factor GLABRA2 (Gl2) played a regulatory role similar to that of VLN1 in hair growth and actin dynamics. Moreover, further analyses demonstrated that VLN1 overexpression suppresses the gl2 mutant phenotypes regarding hair growth and actin dynamics; GL2 directly recognizes the promoter of VLN1 and positively regulates VLN1 expression in root hairs; and the GL2-mediated VLN1 pathway is involved in the root hair growth response to osmotic stress. Our results demonstrate that the GL2-mediated VLN1 pathway plays an important role in the root hair growth response to osmotic stress, and they describe a transcriptional mechanism that regulates actin dynamics and thereby modulates cell tip growth in response to environmental signals.

Root hairs provide a model system to study plant cell differentiation and elongation. Moreover, root hairs contribute to an increase in root surface area for cultivated crops, forming the most critical plant part for water and nutrition absorption. Consequently, they strongly affect plant growth, development, and stress management. For example, water deficiency is caused by various environmental factors, such as drought and osmotic stress (Dolan et al., 1994). Water deficiency-induced root hair growth permits more effective water and nutrition uptake, consequently enhancing tolerance to stress (Sun et al., 2014; He et al., 2015). Numerous root hair growth-related genes are involved in the response to water deficiency, as revealed by gene expression analysis (He et al., 2015); however, few proteins have been identified as functioning in drought-mediated root hair growth using genetic analysis (Sun et al., 2014; He et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018; Wong et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). The deep molecular mechanisms of osmotic stress-mediated root hair growth remain poorly understood.

Root hair cell elongation is regulated by cellular activities such as calcium ion (Ca2+) concentration, reactive oxygen species signals, and actin dynamics (Miller et al., 1999; Ketelaar et al., 2002; Ohashi et al., 2003; He et al., 2006; Pei et al., 2012; Bascom et al., 2018). Additionally, a series of key transcription factors have been identified as core regulatory factors that influence root hair growth (Wada et al., 1997; Lee and Schiefelbein, 1999; Kang et al., 2009; Tao et al., 2013). The homeodomain-Leu-zipper transcription factor GLABRA2 (GL2) plays an important role in organ formation of root hairs, trichomes, and hypocotyl stomata, and in the biosynthesis of mucilage and anthocyanin in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Hülskamp et al., 1994; Ohashi et al., 2003; Schiefelbein, 2003; Pesch and Hülskamp, 2009; Wang et al., 2015). Recently, Lin et al. (2015) found that the gl2-5 mutants have significantly longer root hairs than wild-type seedlings, with similar phenotypes also observed in gl2-1 and gl2-3 mutants (Ketelaar et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2015). Furthermore, GL2 directly suppresses the function of positive hair growth regulators, including basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors RSL2/bHLH85, LRL1, and LRL2, thus negatively regulating root hair cell growth (Lin et al., 2015). The expression of GL2 in hair cells in roots and in root hair cells, although at a low level, indicates that it likely modulates root hair elongation via the bHLH genes (Lee and Schiefelbein, 2002; Becker et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2015).

Higher-order dynamic behavior of the plant actin cytoskeleton is required for root hair growth (Pei et al., 2012; Ketelaar, 2013). The apical and subapical area of root hair cells contains all materials for cellular growth, including the nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (rough), Golgi bodies, endosomes, and ribosomes, and is termed the “tip growth unit” (Carol and Dolan, 2002; Ketelaar, 2013). Fine actin filament bundles (“fine bundles”) in the apex and subapex are required for fast-growing hairs as routes for the delivery of secretory vesicles from or to the plasma membrane for the expanding tip; to prevent penetration of organelles into the apex; and to retain a fixed distance between the nucleus and the tip during the fast elongation phase of root hairs (Miller et al., 1999; Ketelaar et al, 2003; Pei et al., 2012). By contrast, thick actin-filament bundles (“thick bundles”) in the apical and subapical area lead to an inhibition of root hair growth (Miller et al., 1999; Pei et al., 2012). Based on the biochemical activities of actin-binding proteins (ABPs), villin proteins (VLNs) are thought to be the major organizers of the thick bundles in root hairs (Ketelaar et al., 2002; Pei et al., 2012). Injection of an antibody against an Arabidopsis VLN leads to inhibition of the apical and subapical thick bundles, further indicating that VLNs are necessary for forming apical and subapical thick bundles that negatively regulate root hair growth (Ketelaar et al., 2002).

The Arabidopsis genome encodes five VLN proteins, VLN1 to VLN5 (Klahre et al., 2000). Loss of function of VLN4 leads to shorter root hairs, with a significant decline in growth rate during the first 4 h of hair cell elongation, possibly caused by defects in longer actin filaments in the shank of root hair cells, which suggests that VLN4 is required for forming actin bundles in the shank during the fast-growing phase (Zhang et al., 2011). That there are no significant growth and morphology phenotypes of root hairs in vln2 vln3 double mutants (van der Honing et al., 2012) and vln5 single mutants (Zhang et al., 2010) implies that VLN2, VLN3, and VLN5 are not essential for root hair development and growth. To this day, the roles of VLN1 in root hair growth remain poorly understood.

Among Arabidopsis VLN family proteins, VLN1 was the first identified (Klahre et al., 2000). Unlike other VLN family members, VLN1 has no capping, severing, or debundling activities and displays a simple mechanism of bundling capacity in a Ca2+- and calmodulin-insensitive manner (Huang et al., 2005). Analysis of GUS staining reveals that VLN1 is highly expressed in various plant tissues including leaves, hypocotyls, roots, and root hairs (Klahre et al., 2000). VLN1 headpiece domains can associate with actin filaments in leaf, hypocotyl, and root tissues (Klahre et al., 2000). VLN1 and VLN3 have overlapping but distinct activities in the turnover of actin bundle formation in vitro (Khurana et al., 2010). However, the in vivo physiological role of VLN1 is not known.

In this study, we reveal that VLN1 functions as a major bundler of actin filaments in apical and subapical zones of root hairs to regulate root hair growth. This is directly mediated by GL2 at the transcriptional level and the Gl2-VLN1 pathway participates in osmotic stress-induced root hair growth. These results describe in vivo roles of GL2 and VLN1 and detail a key transcriptional regulation mechanism of ABPs in cell tip growth and its responses to environmental stimuli.

RESULTS

VLN1 Negatively Regulates Root Hair Growth by Affecting Growing Time

To distinguish whether VLN1 is involved in root hair growth, we identified two mutants, vln1-1 and vln1-2, with a transfer DNA insertion in the first and second exons (Supplemental Fig. S1A) and constructed VLN1 complementation lines (comps) and overexpression lines (OEs) by transforming the VLN1 promoter (pVLN1)::VLN1 in vln1-2 plants and 35S::VLN1 in Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia (Col-0) plants, respectively. Reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and quantitative real-time PCR analyses showed no detectable VLN1 expression in vln1-1 and vln1-2 (Supplemental Fig. S1, C and F), whereas there was Col-0-like expression in VLN1 comps 9 and 14, ∼2.6-fold higher expression in VLN1 OE7, and ∼6.8-fold higher in VLN1 OE45 (Supplemental Fig. S1, D, E, and F).

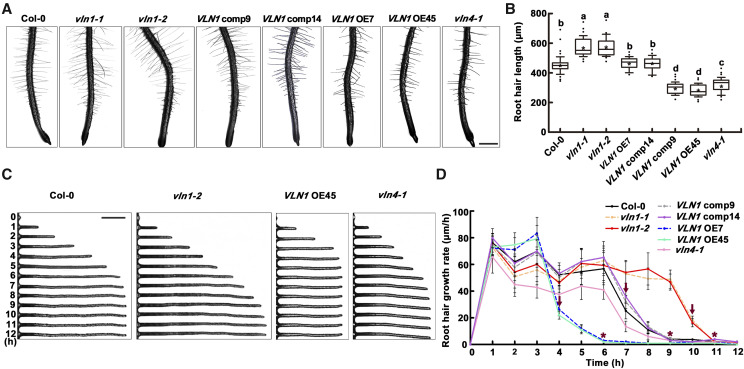

Then, we calculated average root hair length of those root hairs located between 0 and 4 mm from the primary root tip of 6-d-old seedlings from Col-0, vln1-1, vln1-2, VLN1 comp9, VLN1 comp14, VLN1 OE7, VLN1 OE45, and vln4-1. Similar to previous reports (Duan et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Xing et al., 2017), the average length of Col-0 root hairs was ∼450 μm (Fig. 1, A and B). Compared with Col-0, vln4-1, which served as a control mutant, had shorter hairs (Fig. 1, A and B), similar to a previous report (Zhang et al., 2011). Root hairs of vln1-1 and vln1-2 were longer at ∼560 μm (Fig. 1, A and B). The longer root hairs of vln1 mutants were restored in VLN1 comps 9 and 14 (Fig. 1, A and B), confirming that the phenotypes of root hair length in vln1 mutants were caused by VLN1 loss of function. By contrast, seedlings of VLN1 OE7 and VLN1 OE45 had shorter root hairs (Fig. 1, A and B). Interestingly, although VLN1 expression was ∼3-fold higher in VLN1 OE45 than in VLN1 OE7 (Supplemental Fig. S1F), the two OE seedlings showed similar short-hair-length phenotypes (Fig. 1, A and B). This might be interpreted as different VLN1 OE seedlings having similar growth ability in the shorter hair-growth phase and different growth ability in the longer hair-growth phase, suggesting a role for VLN1 in late growth phases. Together, these genetic results illustrate that VLN1 is involved in root hair growth.

Figure 1.

VLN1 regulates root hair growth by mediating growing time. A, Images of root hairs from the wild-type (Col-0), vln1-1, vln1-2, VLN1 comp 9, VLN1 comp 14, VLN1 OE7, VLN1 OE45, and vln4-1. Scale bar = 200 μm. B, Boxplot depicting root hair length in the different VLN1 genotypes. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among genotypes for each condition by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) mean-separation test (P < 0.05). C, Images of root hair growth over time in different genotypes. Scale bar = 100 μm. D, Mean of root hair growth rates in micrometers per hour in different genotypes. The arrows above polylines indicate times of dramatic decline in growth rate, at 4 h for VLN1 OE7 and VLN1 OE45, 7 h for Col-0, VLN1 comp9 and VLN1 comp14, and 10 h for vln1-1 and vln1-2. Asterisks above polylines represent the beginning of the fully grown phase, at 6 h for VLN1 OE7 and VLN1 OE45; 9 h for Col-0, VLN1 comp9, and VLN1 comp14; and 11 h for vln1-1 and vln1-2. Values represent means ± se. Images and data in A and B show average lengths of root hairs located in the area between 0 and 4 mm from the root tip of 6-d-old seedlings in >30 individual roots (n > 500 hairs). In C and D, root hair growth was measured from the bulges of 3-d-old seedlings to the 12 h time point, and the data presented are for >30 individual roots (n > 100 hairs).

Root hair growth is divided into four phases: initiation (bulge formation), the fast-growing phase, the terminating-growth/slow-growing phase, and the fully grown phase (Miller et al., 1999; Pei et al., 2012). To further test in which root hair growth phases VLN1 functions, we calculated the rate of root hair growth in Col-0 and different VLN1 genotype seedlings at 1-h intervals for 12 h from the initiation of bulge formation. Col-0 hairs grew rapidly at ∼50 to 70 μm h−1 during the first 6 h (the fast-growing phase), then displayed a significantly decreased growth rate by 7 h, when entering the terminating-growth phase, and by 9 h, as it entered the fully grown phase, was hardly growing (Fig. 1, C and D). Compared with Col-0, vln1 mutants had slightly lower growth rates in the first 3 h and, remarkably, continued to grow rapidly until 10 h, after which growth slowed precipitously and almost stopped by 11 h (Fig. 1, C and D), demonstrating that the significantly longer root hairs of vln1 mutants result from longer growing times, especially in the fast-growing phase. By contrast, the shorter root hairs of VLN1 OE seedlings were associated with an ∼3-h shorter growing time compared with that of Col-0 (Fig. 1, C and D). These results suggest that VLN1 is involved in root hair growth by regulating growing time.

VLN1 Decorates Bright Filaments in Root Hairs

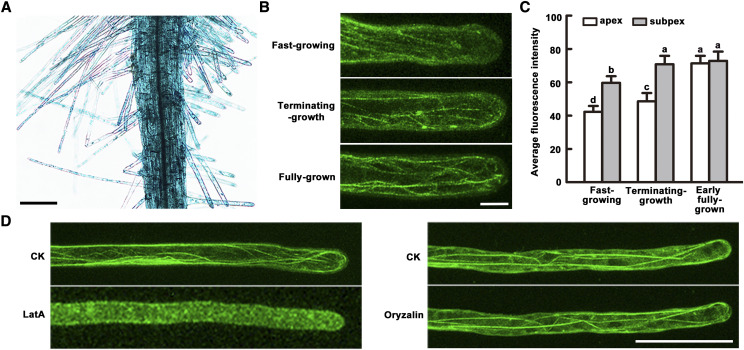

Fine bundles in the subapex and apex in hair cells are essential for root hair cell fast elongation, whereas thick bundle formation in the subapex and apex suppresses root hair growth (Miller et al., 1999; Ketelaar et al., 2002, 2003; Pei et al., 2012). Therefore, we proposed that the actin-bundling protein VLN1 might play a key role in forming thick bundles in the subapical and apical areas of root hairs to regulate growing time. Thus, we first determined whether VLN1 is expressed in root hairs, especially focusing on its subcellular localization in the subapical and apical area. pVLN1::GUS staining analysis revealed that VLN1 was highly expressed in root hairs, including short and long hairs (Fig. 2A), similar to a previous report by Klahre et al. (2000). The introduction of a pVLN1::VLN1-GFP construct into vln1-2 fully rescued the root hair phenotype of vln1-2 (Supplemental Fig. S2), demonstrating that the GFP fusion protein may be used in the subcellular localization of VLN1. VLN1 decorated several bright filaments in root hairs (Fig. 2, B and D), similar to previous findings showing that VLN1 colocalizes with actin filaments in leaf, hypocotyl, and root tissues (Klahre et al., 2000). In fast-growing hairs, weak filaments were found in the subapical area and filaments in the apical area were not visible (Fig. 2B). In terminating-growth hairs, clear and bright filaments were located in the subapical area, but no clear short filaments were observed in the apical area (Fig. 2B). In fully grown hairs, long and brighter filaments extended to the apex (Fig. 2, B and D). Consistent with the contribution of filaments in various growth phases, the average GFP fluorescence was higher in the terminating-growth and fully grown hairs than in fast-growing hairs (Fig. 2C). These results illustrate that VLN1 expression is consistent with the function of VLN1 in the terminating- growth and fully grown phases. Moreover, the filamentous structures were disrupted by the microfilament-depolymerizing drug Latrunculin A (LatA), but not by the microtubule-depolymerizing drug oryzalin, after 1 μm treatment for 3 min (Fig. 2D), confirming that VLN1 specifically functions on microfilaments. Together these results indicate that VLN1 colocalizes with actin filaments in root hairs in the apex, subapex, and shank.

Figure 2.

VLN1 decorates bright filaments in subapical and apical regions of root hairs. A, GUS activity of 4-d-old seedlings carrying the pVLN1::GUS reporter gene. Scale bar = 100 μm. B, Images of pVLN1::VLN1-GFP seedlings in various growth phases. Scale bar = 10 μm. C, Average fluorescence intensity of root hairs in various growth phases in pVLN1::VLN1-GFP seedlings. Fluorescence intensity was quantified by measuring the GFP fluorescence pixel intensity in subapical and apical regions of root hairs using ImageJ. The average value was calculated for >30 root hairs of >15 individual roots. Values represent the mean ± se. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among genotypes for each condition using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD mean-separation test (P < 0.05). D, pVLN1::VLN1-GFP seedlings treated with 1 μm LatA and 1 μm oryzalin for 3 min compared to controls (CK). Scale bar = 50 μm.

VLN1 Is Required for Organizing Subapical and Apical Thick Bundles in Terminal-Growth and Fully Grown Phases in Root Hairs

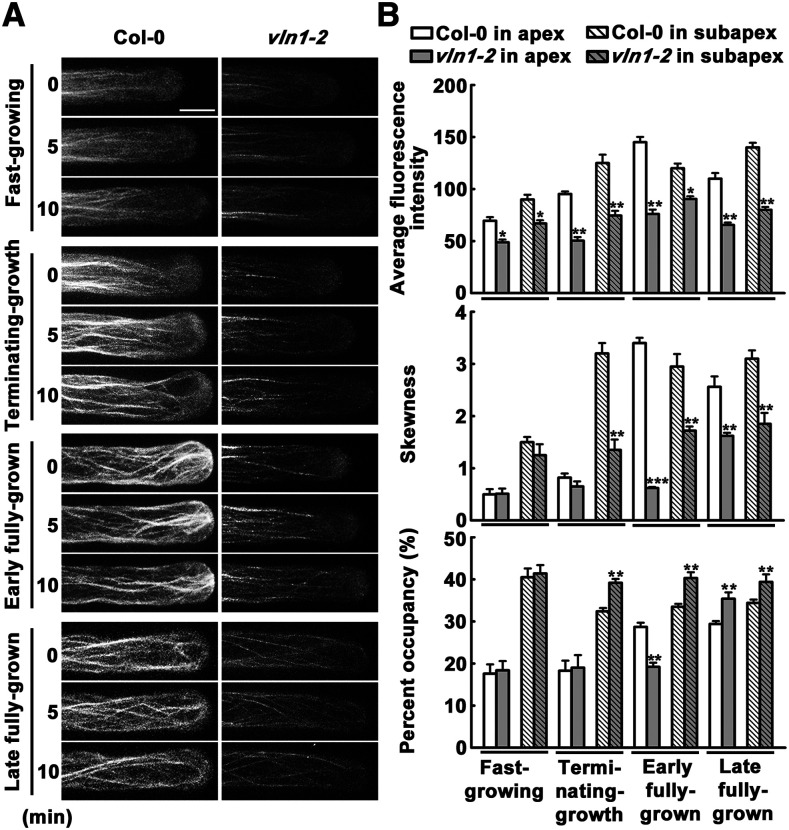

To explore actin dynamic mechanisms of VLN1 in thick bundles in the subapex and apex in root hair cells, we used an ideal actin filament-specific fluorescent probe, fABD2-GFP (Li et al., 2012, 2015), to observe actin-filament dynamics in Col-0 and vln1-2. To quantify actin organization, we used average fluorescence of actin staining to reveal the presence of bright actin filaments that generally resulted from thick bundles (Zou et al., 2019), the skewness parameter to indicate the presence of thick bundles, and the percentage of occupancy to estimate the amount of actin filaments (Li et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015). According to previous reports (Miller et al., 1999; Ketelaar et al., 2002; He et al., 2006; Pei et al., 2012) and our above data, the fast-growing, terminating-growth, early fully grown, and late fully grown phases were selected using root hairs in the 4- to 5-, 8- to 9-, 10- to 11-, and 11- to 12-h growth periods, respectively. The fully grown phase was represented by two time points (i.e. early and late) because of the different growth rate in early and late fully grown phases in vln1 (Fig. 1, C and D).

Similar to a previous report (Miller et al., 1999), we found that fast-growing Col-0 hairs possessed several growth-axially aligned fine bundles in the subapex and no significant visible bundles in the apex (Fig. 3A). Fast-growing vln1 showed actin arrays similar to those of Col-0 (Fig. 3). In the terminating-growth phase, Col-0 hairs possessed several thick bundles in the subapex and no significant visible bundles in the apex (Fig. 3A), as found previously (Miller et al., 1999). However, compared with Col-0, vln1 displayed significant defects in thick bundles and more fine bundles in the subapical area, and no visible bundles in the apex in the terminating-growth phase (Fig. 3A), creating actin arrays comparable to those in fast-growing Col-0 hairs. This result was consistent with lower fluorescence intensity and skewness parameter and higher percentage of occupancy in the subapex, and similar values f or all of these parameters in the apex, in vln1 compared with Col-0 (Fig. 3B). In the early fully grown phase, the Col-0 thick bundles extended from subapex to apex; however, vln1 still showed defects in thick bundles in the subapex and invisible bundles in the apex, consistent with lower fluorescence intensity, lower skewness parameter, and higher percentage of occupancy in the subapex and apex in vln1 (Fig. 3). In the late fully grown phase, thick bundles in Col-0 and fine bundles in vln1 mutants looped through the extreme apex (Fig. 3A). In summary, VLN1 loss of function leads to serious defects in subapical and apical thick bundles in terminating-growth and fully grown phases, which is consistent with the location of VLN1.

Figure 3.

VLN1 loss of function leads to defects in subapical and apical thick bundles in root hair growth. A, Time-lapse images of actin filaments in Col-0 and vln1 root hair growth at 0, 5, and 10 min of the different growth periods. Scale bar = 10 μm. B, Average fluorescence intensity, skewness, and percentage occupancy of root hairs in different growth periods in Col-0 and vln1. The relative amount of actin filaments (fluorescence intensity) was quantified by measuring the fluorescence pixel intensity in subapical and apical regions of root hairs. The average value was calculated from >60 root hairs in >30 individual roots. The extent of actin filament bundling (skewness) and the abundance of actin filaments (percentage occupancy) were measured on the images using ImageJ and binned for the same regions (see “Materials and Methods” for details). Values represent the mean ± se. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared with Col-0, as determined by Student’s t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001).

VLN1 Is Required for Actin Bundling in Subapical and Apical Area in Root Hairs

Previous findings have shown that VLN1 has no capping, severing, or de-bundling activities and displays a simple mechanism of bundling capacity in vitro (Huang et al., 2005; Khurana et al., 2010). Therefore, we put our efforts toward characterizing the actin bundling capacity of VLN1 in vivo. We traced the bundle formation process and quantified the bundling and debundling frequencies in Col-0 and vln1-2 hairs on a single-filament level by the live-cell imaging method as described previously (Zheng et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2015). Two Col-0 adjacent bright, fine actin filaments were zipped together with bundling thick actin filaments in the subapical and apical area for several seconds (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Movies S1 and S2). By contrast, two vln1 adjacent fine actin filaments in the subapical and apical area were not bundled to form thick actin filaments (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Movies S3 and S4), consistent with the dramatic decline in bundling frequency for vln1 (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that VLN1 loss of function leads to serious defects in actin-filament bundling activity in the subapical and apical area of root hairs.

Figure 4.

VLN1 loss of function leads to defects in actin filament bundling activity in subapical and apical areas of root hairs. A, Dynamics of single actin filaments in Col-0 and vln1 root hairs. Yellow and blue dots indicate a fine bundle of actin filaments and red dots indicate a thick bundle of actin filaments. Scale bar = 10 μm. B, Quantification of bundling and debundling rates in different regions of Col-0 and vln1 root hair. The data for every parameter presented was assessed in >30 individual roots (n > 60 hairs). Values represent means ± se. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared with Col-0, by Student’s t test (***P < 0.001).

Considering that loss of actin filament bundling in cells leads to an increase of actin filament turnover (Huang et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2015), we further calculated several other dynamic parameters on a single-filament level, including severing frequency, depolymerization frequency, maximum filament length, and maximum filament lifetime in vln1 mutants during the terminating-growth phase as described previously (Henty et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2015). vln1 mutants showed increased rapid turnover based on the increasing severing frequency and depolymerization frequency, as well as the decreasing maximum filament length and maximum filament lifetime in the apical and subapical area (Table 1), further indicating that VLN1 is required for bundling actin filaments in apical and subapical zones of root hairs. Combined, our results illustrate that VLN1 is responsible for actin bundling to form thick bundles in the subapex and apex during the terminating-growth and fully grown phases that inhibit fast elongation of root hair cells.

Table 1. Quantification of parameters associated with single actin dynamics in the subapex and apex of Col-0 and vln1-2 root hairs.

Actin filaments were counted in >30 individual roots (n >60 root hairs). Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared with Col-0, determined by Student’s t test (*P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001).

| Stochastic Dynamic | Terminating-Growth Phase | |

|---|---|---|

| Col-0 | vln1-2 | |

| Severing frequency (breaks μm−1 s−1) | 0.018 ± 0.005 | 0.0241 ± 0.032* |

| Depolymerization rate (μm s−1) | 0.584 ± 0.043 | 1.337 ± 0.06*** |

| Max filament length (μm) | 19.283 ± 1.5 | 18.054 ± 1.3* |

| Max filament life time (s) | 79.8 ± 3.07 | 49.5 ± 2.76*** |

VLN1 Inhibits Root Hair Growth by Organizing Thick Bundles

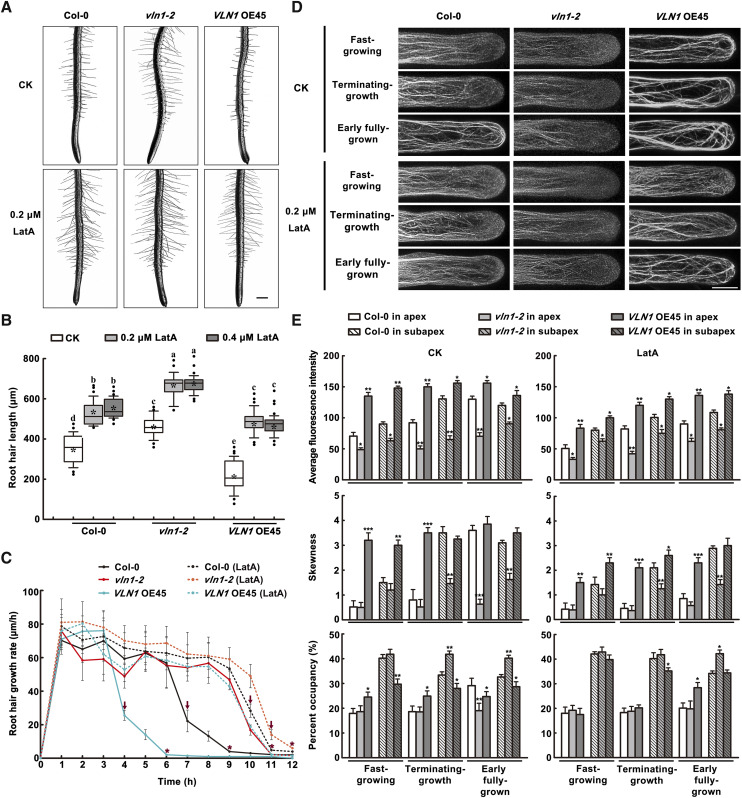

To confirm that VLN1 regulates root hair growth by organizing thick bundles, we further conducted actin pharmacological experiments. We examined root hair length, hair growth rate, and actin dynamics in Col-0, vln1-2, and VLN1 OE45 seedlings from 3-d-old seedlings treated or not with the actin-disrupting drug LatA for 3 h then cultured in drug-free one-half strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) media for 3 d. When 0.2 and 0.4 μm LatA were added, root hair length and hair growing time were increased in Col-0, vln1-2, and VLN1 OE45 seedlings (Fig. 5, A and C). No significant difference in LatA-induced root hair growth between 0.2 and 0.4 μm was found (Fig. 5B). Further analysis showed that, compared with control conditions, Col-0 hairs showed fast growth rates under LatA treatment during the terminating-growth and early fully grown phases, which was associated with defects in the subapical and apical thick bundles during those phases, and vln1 hairs displayed faster growth rates during the early fully grown phase, associated with fine bundles in the subapex and invisible bundles in the apex (Fig. 5D). Remarkably, LatA treatments rescued the shorter hair length, shorter growing time, and earlier subapical and apical thick-bundle-formation phenotypes in VLN1 OE seedlings. Our experiments illustrate that an actin-disrupting drug blocks VLN1-mediated subapical and apical thick bundle formation, and so increases the root hair growing time and root hair length (Fig. 5, D and E). Pharmacological results confirm that VLN1 inhibits fast cell elongation through organizing thick bundles in root hairs.

Figure 5.

VLN1-mediated actin bundles are important for inhibiting root hair growth. A, Images of root hairs from Col-0, vln1-1, and VLN1 OE45 with and without LatA treatment. Scale bar = 200 μm. B, Boxplot depicting root hair length in Col-0, vln1-1, and VLN1 OE45 with LatA treatment. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among genotypes for each condition by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) mean-separation test (P < 0.05). C, Mean of root hair growth rates in micrometers per hour in Col-0, vln1-1, and VLN1 OE45 with and without LatA treatments. Arrows above polylines represent times of dramatic decline in growth rate, at 4 h for VLN1 OE45; 7 h for Col-0; 10 h for vln1-2, LatA-treated Col-0, and LatA-treated VLN1 OE45; and 11 h for LatA-treated vln1-2. Asterisks above polylines represent the beginning of the fully grown phase, at 6 h for VLN1 OE45; 9 h for Col-0; 11 h for vln1-2, LatA-treated Col-0, and LatA-treated VLN1 OE45; and 12 h for LatA-treated vln1-2. Values represent means ± se. D, Images of actin filaments in Col-0, vln1-1, and VLN1 OE45 in each growth phase with and without LatA treatment. Scale bar = 10 μm. E, Average fluorescence intensity, skewness, and percentage occupancy of root hairs in various growth phases in Col-0, vln1-1, and VLN1 OE45 with and without LatA treatment. The relative amount of F-actin (fluorescence intensity) was quantified by measuring the fluorescence pixel intensity in subapical and apical regions of root hairs. The average value was calculated in >60 root hairs of >30 individual roots. The extent of actin filament bundling (skewness) and the abundance of actin filaments (percentage occupancy) were measured on the images using ImageJ and binned for the same regions (see “Materials and Methods” for details). Values represent means ± se. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared with Col-0, by Student’s t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001).

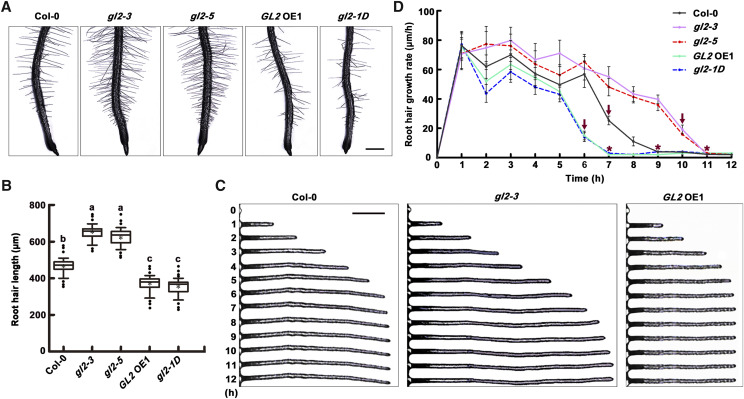

GL2 Displays an Effect Similar to That of VLN1 in Regulating Root Hair Growth

GL2 plays an important role in root hair growth (Lin et al., 2015). It is well known that GL2 recognizes the L1 box-like site of the target gene promoter (Lin et al., 2015). Given the presence of a L1 box-like site in the VLN1 promoter and the significantly longer root hairs of gl2 mutants, resembling those of vln1 mutants, it seemed likely that GL2 might act as a direct upstream factor regulating VLN1 transcription in root hair growth. Therefore, we calculated average hair length and hair growth rate in Col-0, two lines of gl2 mutants (gl2-3 and gl2-5; Lin et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015), and two lines of GL2 OE seedlings (GL2 OE1 and gl2-1D; Supplemental Fig. S3; Wang et al., 2015). The average length of Col-0 root hairs was ∼450 μm (Fig. 6, A and B), whereas gl2-3 and gl2-5 root hair length exceeded ∼600 μm (Fig. 6, A and B). By contrast, GL2 OE1 and gl2-1D seedlings had shorter root hairs (Fig. 6, A and B). Furthermore, compared with Col-0, gl2-3 and gl2-5 root hairs showed faster growth rates in the fast-growing phase and, remarkably, grew rapidly until 10 h and almost stopped at 11 h, thus indicating that gl2 mutants displayed longer growing times, especially in the fast-growing phase, similar to vln1 mutants (Fig. 6, C and D). By contrast, GL2 OE seedlings had a lower growth rate in the fast-growing phase and an ∼2 h shorter growing time (Fig. 6, C and D). Therefore, genetic analyses illustrate that GL2 has an effect similar to that of VLN1 in regulating root hair growing time.

Figure 6.

GL2 regulates root hair growing time. A, Images of root hairs from the Col-0, gl2-3, gl2-5, GL2 OE1, and gl2-1D. Scale bar = 200 μm. B, Boxplots depicting root hair length in Col-0 and the different GL2 genotypes. Center lines of boxes represent the median with outer limits at the 25th and 75th percentiles. Altman whiskers extend to the 5th and 95th percentiles, outliers are depicted as black dots, and the asterisks mark sample means. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among genotypes for each condition by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD mean-separation test (P < 0.05). Root hair length was measured in root hairs between 0 and 4 mm of the root tips of 6-d-old seedlings in >30 individual roots (n > 500 hairs). C, Images of root hair growth measured in micrometers per hour in the different GL2 genotypes. Scale bar = 100 μm. D, Mean of root hair growth rates in micrometers per hour in different GL2 genotypes. Arrows above polylines represent times of dramatic decline in growth rate, at 6 h for GL2 OE1 and gl2-1D, 7 h for Col-0, and 10 h for gl2-3 and gl2-5. Asterisks above polylines represent the beginning of the fully grown phase, at 7 h for GL2 OE1 and gl2-1D, 9 h for Col-0, and 11 h for gl2-3 and gl2-5. Values represent means ± se. In C and D, root hair growth was measured from the bulges of 3-d-old seedlings each hour for 12 h in >30 individual roots (n > 100 hairs).

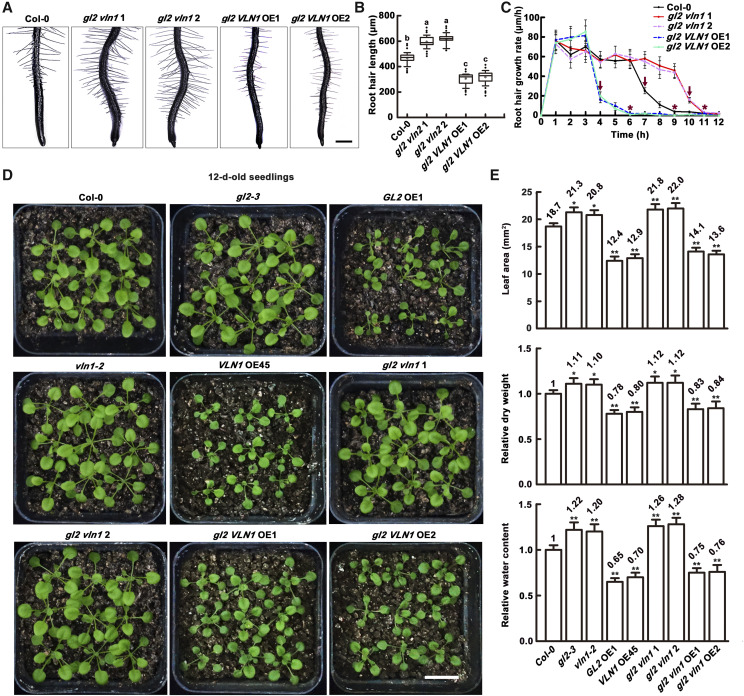

Overexpressing VLN1 Suppresses the Root-Hair and Plant-Growth Phenotypes of gl2 Mutants

To explore whether VLN1-mediated root hair growth is regulated by GL2, we examined root hair lengths and growth rates of various genotypes, including gl2 vln1 1 and gl2 vln1 2 double mutants created by crossing gl2-3 and vln1-2, and gl2 VLN1 OE1 and gl2 VLN1 OE2 seedlings created by crossing gl2-3 and VLN1 OE45 (Supplemental Fig. S4). Two lines of gl2 vln1 double mutants had longer hairs than Col-0 (Fig. 7, A and B), associated with an ∼3 h longer growing time (Fig. 7C), and were generally similar to vln1 single mutants (Figs. 1 and 6). By sharp contrast, two lines of gl2 VLN1 OE seedlings had significantly shorter root hairs (Fig. 7, A and B), reflecting an ∼3 h shorter growing time (Fig. 7C), similar to phenotypes of VLN1 OE seedlings (Fig. 1). These results indicate that the longer hairs and growing times of gl2 are rescued by VLN1 overexpression. Therefore, GL2 likely activates the physiological function of VLN1 in root hair growth.

Figure 7.

Overexpressing VLN1 suppresses the phenotypes of root hair and plant growth in gl2 mutants. A, Images of root hairs from Col-0, gl2 vln1 1, gl2 vln1 2, gl2 VLN1 OE1, and gl2 VLN1 OE2 in micrometers per hour. Scale bar = 200 μm. B, Boxplots depicting length of the root hairs in A. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among genotypes for each condition by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD mean-separation test (P < 0.05). C, Mean of root hair growth rates from the different genotypes in micrometers per hour. Arrows above polylines represent times of dramatic decline in growth rate, at 4 h for gl2 VLN1 OE1 and gl2 VLN1 OE2, 7 h for Col-0, and 10 h for gl2 vln1 1 and gl2 vln1 2. The asterisks above polylines represent initiation of the fully grown phase, at 6 h for gl2 VLN1 OE1 and gl2 VLN1 OE2, 9 h for Col-0, and 11 h for gl2 vln1 1 and gl2 vln1 2. Values represent means ± se. Root hair growth was measured from the bulges of 3-d-old seedlings each hour for 12 h and the data presented are from >30 individual roots (n > 100 hairs). D, Images of 12-d-old seedlings from Col-0, gl2-3, vln1-2, GL2 OE1, VLN1 OE45, gl2 vln1 1, gl2 vln1 2, gl2 VLN1 OE1, and gl2 VLN1 OE2. Scale bar = 1 cm. E, Leaf area, relative dry weight, and relative water content from 12-d-old plants of different genotypes under normal conditions. Dry weight and water content were counted in >60 seedlings of the various genotypes. Dry weight and water content in Col-0 are set at 1. Values for the various genotypes were calculated relative to that of Col-0. At least 60 plants were measured with three technical and biological replicates. Values represent means ± se. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared with Col-0, by Student’s t test (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01).

Next, we examined the effect of GL2 and VLN1 on plant growth. Compared with Col-0, gl2-3, vln1-2, and gl2 vln1 1 mutants displayed larger leaf areas, higher dry weights, and higher water contents, but GL2 OE1, VLN1 OE45, and gl2 VLN1 OE1 seedlings showed contrasting results in normal conditions (Fig. 7, D and E), suggesting that root hair growth mediated by GL2 and VLN1 negatively regulates water uptake and plant growth, and that GL2 activates the physiological function of VLN1 in water uptake and plant growth.

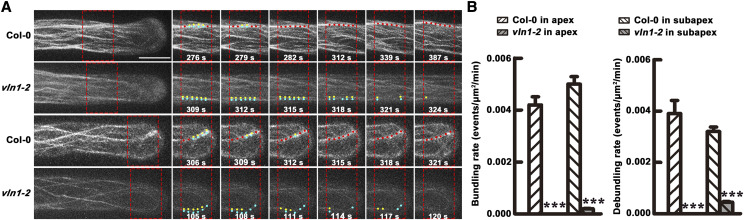

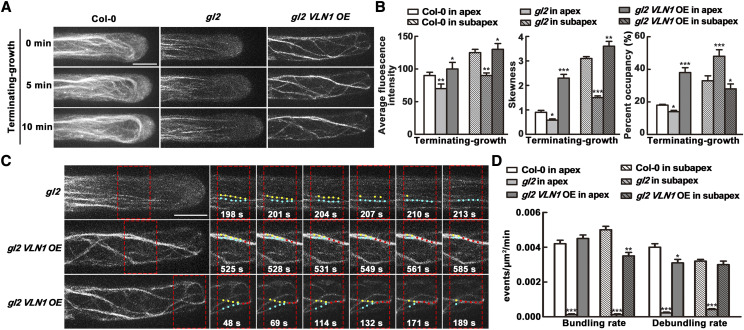

GL2 Regulates VLN1-Mediated Actin Bundling in the Subapex and Apex in Root Hairs

To further test that GL2 regulates VLN1 function in root hair growth, we calculated the thick bundles and bundling thick filament process in the subapical and apical area of Col-0, gl2-3, and gl2 VNL1 OE hairs in the terminating-growth phase. We selected the terminating-growth phase because the phenotype of longer growing time in gl2-3 is recovered in gl2 VNL1 OE seedlings in the terminating-growth phase, and the most significant difference in hair growth rate between gl2-3 and gl2 VNL1 OE is during the terminating-growth phase (Fig. 8, A and B). The results showed that gl2 displayed defects in thick bundles in the subapical and apical area in the terminating-growth phase, similar to vln1 mutants (Fig. 3A), indicating that GL2 has an effect similar to that of VLN1 on the formation of thick bundles in root hair growth. gl2 VLN1 OE seedlings had thick bundles in the subapical and apical areas (Fig. 8, A and B), similar to Col-0 in the fully grown phase (Fig. 3A), indicating that VLN1-mediated thick bundles are regulated by GL2 in root hair growth. Furthermore, gl2 displayed defects in actin filament bundling frequency in the subapical and apical areas, which was rescued by VLN1 OE (Fig. 8, C and D; Supplemental Movies S5–S7). Combined, these results indicate that GL2 regulates the function of VLN1 in bundling actin filaments in the subapex and apex of root hairs.

Figure 8.

GL2 regulates VLN1-mediated actin bundling in the subapex and apex of root hairs. A, Time-lapse images of actin filaments in Col-0, gl2, and gl2 VLN1 OE root hairs at 0, 5, and 10 min in the terminating-growth period. Scale bar = 10 μm. B, Average fluorescence intensity, skewness, and percentage occupancy of root hairs in Col-0, gl2, and gl2 VLN1 OE in the terminating-growth period. The relative amount of F-actin (fluorescence intensity) was quantified by measuring the fluorescence pixel intensity in subapical and apical regions of root hairs. The average value was calculated for >60 root hairs of >30 individual roots. The extent of actin filament bundling (skewness) and the abundance of actin filaments (percentage occupancy) were measured on the images using ImageJ and binned for the same regions (see “Materials and Methods” for details). C, Dynamics of single actin filaments in gl2 and gl2 VLN1 OE root hairs. Yellow and blue dots indicate fine bundles of actin filaments and red dots indicate a thick bundle of actin filaments. Scale bar = 10 μm. D, Quantification of bundling and de-bundling rates of actin filaments in Col-0, gl2, and gl2 VLN1 OE root hairs. For B and D, Values represent means ± se. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared with gl2, determined by Student’s t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001). The data are based on measurements in >30 individual roots (n > 60 hairs).

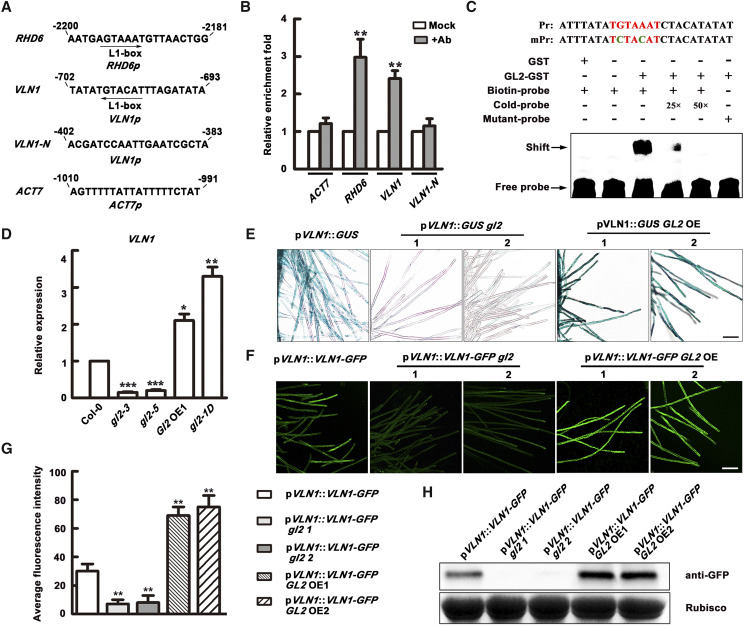

GL2 Directly Recognizes VLN1 and Regulates VLN1 Expression in Root Hairs

To determine whether GL2 directly regulates VLN1 at the transcriptional level, we tested for any physical interaction of GL2 with VLN1 genes by chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis using GL2 OE1 seedlings with anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibodies (Wang et al., 2015). We confirmed that GL2 OE1 was functionally equivalent to GL2 OE in root hair growth by comparing GL2 OE1 with gl2-1D phenotypes in root hairs (Fig. 6, C and D). The ChIP assays revealed that the short DNA regions of VLN1 and the positive control RHD6 were significantly enriched in coimmunoprecipitates, whereas both a negative control region of VLN1 and the ACT7 negative control were not, indicating that GL2 directly binds to the VLN1 promoter in vivo (Fig. 9B). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were further used to test the direct binding of Gl2 to the VLN1 promoter in vitro using 5- (and 6-) carboxytetramethylrhodamine succinimidylester-biotin-labeled DNA fragments of the VLN1 promoter. The GST-GL2-His proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified from the soluble fraction with an anti-His antibody. The obvious binding signals of the biotin-labeled DNA fragment incubated with the GST-GL2 protein were observed. The binding signals were generally reduced by added increasing amounts of unlabeled cold probes (Fig. 9C), which confirmed the binding specificity. These results demonstrate that VLN1 is a direct target gene of GL2.

Figure 9.

GL2 recognizes VLN1 and positively regulates the VLN1 transcription in root hairs. A, TAAATGTT/A L1-boxes in the promoter regions of RHD6 and VLN1 genes and random sequences in the promoter regions of VLN1 and ACT7 genes as negative controls. Arrows indicate sequences and numbers indicate the nucleotide position relative to the gene start codon. B, Quantification of ChIP-qPCR with HA-35SE-pGL2::GL2 transgenic plants (GL2 OE1) using anti-HA antibodies. Rabbit preimmune serum was used as a mock control. RHD6 served as a positive control, and ACT7 and VLN1-N as negative controls. Data represent the means ± sd of three replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared with the mock control, determined by Student’s t test (**P < 0.01). C, EMSA for GL2 binding to the VLN1 promoter in vitro. Biotin-labeled promoter sequences added an excess of unlabeled cold probes for competition. The mutated biotin-labeled promoter (mPr) was used to assess binding specificity. TGTAAAT sequences are mutated in the mPr probe to TCTACAT. Arrows indicate the binding signals resulting from GL2 binding to the VLN1 promoter. D, Relative expression levels of VLN1 in root hairs of 6-d-old seedlings of Col-0, gl2-3, gl2-5, GL2 OE1, and gl2-1D. Data represent the mean ± sd of three replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared with Col-0, determined by Student’s t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and***P < 0.001). E, GUS activity of the different genotypes measured in 4-d-old seedlings carrying the pVLN1::GUS reporter gene. Scale bar = 100 μm. F, pVLN1::VLN1-GFP activity of the different genotypes measured in 4-d-old seedlings carrying the pVLN1::VLN1-GFP gene. Scale bar = 100 μm. G, Average fluorescence intensity of different genotypes carrying the pVLN1::VLN1-GFP gene. Fluorescence intensity was quantified by measuring the GFP fluorescence pixel intensity in the images of root hairs using ImageJ. The average value was calculated in >100 root hairs from >15 individual roots. Values represent means ± se. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared with pVLN1::VLN1-GFP seedlings, determined by Student’s t test (**P < 0.01). H, Western blots using proteins extracted from different genotypes carrying the pVLN1::VLN1-GFP gene. Rubisco was used as a loading control.

Moreover, qRT-PCR analysis showed that VLN1 expression in root hairs was almost fully inhibited in gl2-3 and gl2-5 mutants but was significantly increased in GL2 OE1 and gl2-1D (Fig. 9D), illustrating the positive regulatory role of GL2 in VLN1 expression in root hairs. This was further verified by introducing the pVLN1::GUS construct into gl2-3 and GL2 OE1 by genetic crossing (Fig. 9E). GL2-regulated VLN1 expression at the protein level was demonstrated in root hairs using GFP fluorescence signal and western blot analyses following introduction of the pVLN1::VLN1-GFP construct into gl2-3 and GL2 OE1 seedlings (Fig. 9, F–H). These results corroborate that GL2 directly recognizes and positively regulates VLN1 at the transcriptional and protein levels in root hairs.

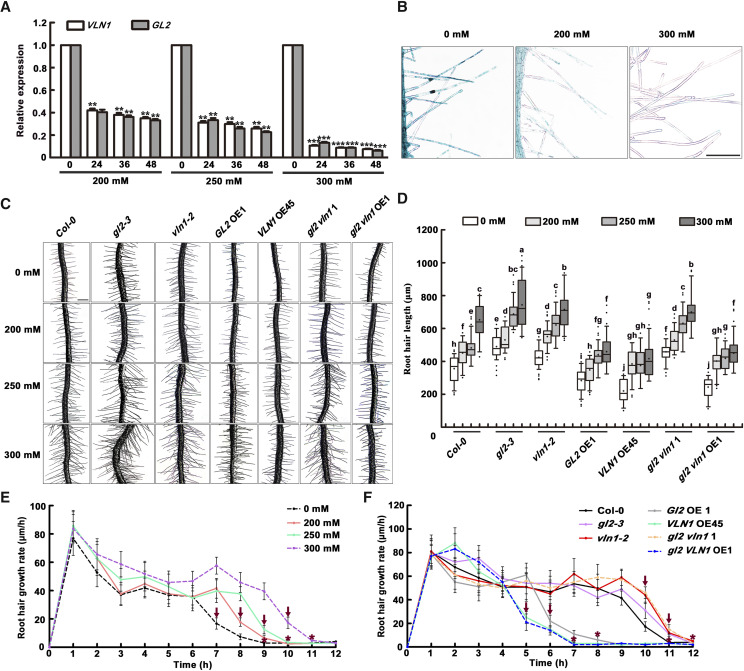

The GL2-VLN1 Pathway Negatively Responds to Osmotic Stress-Induced Root Hair Growth

Microarray data showed that osmotic stress inhibited expression of both GL2 and VLN1 in roots (Schmid et al., 2005). We therefore considered whether GL2-VLN1 pathway-mediated root hair growth plays a role in the root hair response to osmotic stress. qRT-PCR analysis showed that the expression of GL2 and VLN1 in root hairs was significantly inhibited by mannitol treatment at different concentrations, and that the osmotic stress-mediated inhibitory effect on expression of both genes was largely dependent on mannitol concentration (Fig. 10A), which was verified by pVLN1::GUS staining (Fig. 10B).

Figure 10.

The GL2-VLN1 pathway negatively responds to osmotic stress-induced root hair growth by regulating growing time. A, Relative expression level of VLN1 and GL2 in root hairs of 6-d-old seedlings with 0, 200, 250, and 300 mm mannitol treatments for different time periods. Data represent the mean ± sd of three replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared with genotype expression at 0 h in the different mannitol treatments, as determined by Student’s t test (**P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001). B, GUS activity of 4-d-old seedlings carrying the pVLN1::GUS reporter gene with 0, 200, 250, and 300 mm mannitol treatments. Scale bar = 100 μm. C, Images of root hairs from seedlings of the indicated genotypes under 0, 200, 250, and 300 mm mannitol treatment. Scale bar = 200 μm. D, Boxplots depicting root hair length in different genotypes under 0, 200, 250, and 300 mm mannitol treatment. Root hair length was measured in root hairs located between 2 and 4 mm from the root tip of 6-d-old seedlings in >30 individual roots (n > 500 hairs). Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among genotypes for each condition by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD mean-separation test (P < 0.05). E, Mean root hair growth rates of Col-0 seedlings under 0, 200, 250, and 300 mm mannitol treatment in micrometers per hour. Arrows above polylines represent time points of dramatic decline in growth rate, at 7 h for 0 mm mannitol, 8 h for 200 mm mannitol, 9 h for 250 mm mannitol, and 10 h for 300 mm mannitol. Asterisks above polylines represent the beginning of the fully grown phase, at 9 h for 0 mm mannitol, 10 h for 200 and 250 mm mannitol, and 11 h for 300 mm mannitol. F, Mean root hair growth rates of the indicated genotypes under 300 mm mannitol treatment in micrometers per hour. Arrows above polylines represent times of dramatic decline in growth rate, at 5 h for VLN1 OE45 and gl2 VLN1 OE1, 6 h for GL2 OE1, 10 h for Col-0, and 11 h for gl2-3, vln1-2, and gl2 vln1 1. The asterisks above Polylines represent the beginning of the fully grown phase, at 7 h for VLN1 OE45 and gl2 VLN1 OE1; 8 h for GL2 OE1; 11 h for Col-0; and 12 h for gl2-3, vln1-2, and gl2 vln1 1. Values represent means ± se. In E and F, growth rate is based on root hair growth from the bulges to the 12 h time point in 4-d-old seedlings after 24 h mannitol treatment, and the data presented are from >30 individual roots (n > 100 hairs).

Next, we calculated root hair length and growth rate in Col-0, gl2-3, vln1-2, Gl2 OE1, VLN1 OE45, gl2 vln1 1, and gl2 VLN1 OE1 seedlings following mannitol treatment at various concentrations. The higher mannitol concentrations led to increased length of Col-0 hairs (Fig. 10, C and D). Compared with Col-0, gl2, vln1, and gl2 vln1 had longer hairs, but GL2 OE1, VLN1 OE45, and gl2 VLN1 OE1 seedlings had much shorter hairs under mannitol treatment (Fig. 10, C and D). Further analysis showed that osmotic stress-induced hair growth was associated with a faster growth rate and a significantly longer growing time (Fig. 10E). Interestingly, osmotic stress-increased growing time was dependent on increasing mannitol concentration, consistent with the osmotic stress-regulated GL2 and VLN1 expression mode depending on increasing mannitol concentration in root hairs. Furthermore, compared with Col-0, gl2-3, vln1-2, and gl2 vln1 1 double mutants displayed 1 h longer growing times, but GL2 OE1, VLN1 OE45, and gl2 VLN1 OE1 seedlings showed 4 h shorter growing times under 300 mm mannitol treatment (Fig. 10F). This suggests that, compared with controls, the differences in growing time are significantly amplified between Col-0 and GL2 OE, VLN1 OE, and gl2 VLN1 OE seedlings, but only slightly amplified between Col-0 and gl2, vln1, and gl2 vln1 seedlings under osmotic stress, consistent with inhibited expression of GL2 and VLN1 in root hairs under osmotic stress.

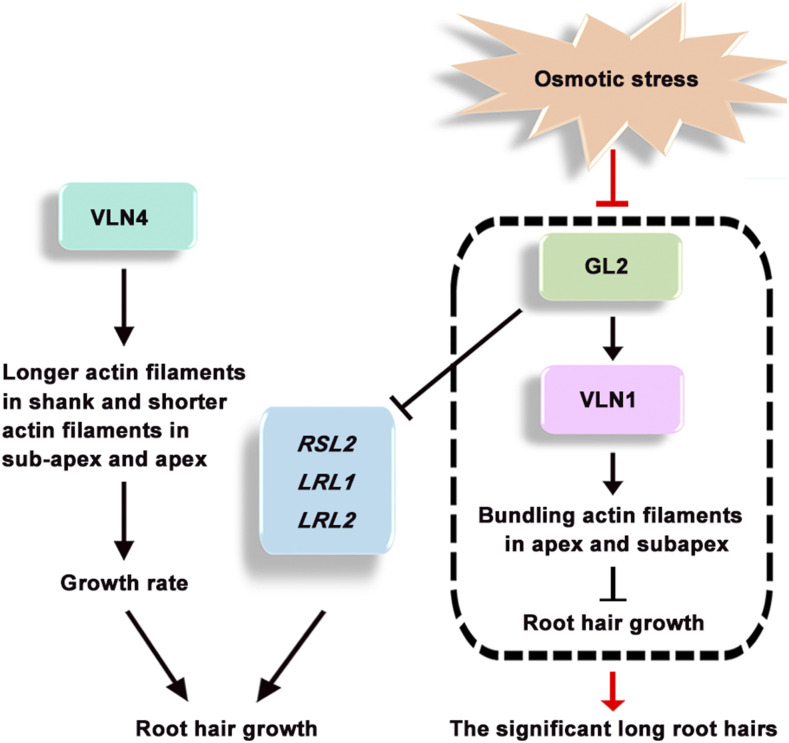

The results indicate that osmotic stress inhibits the expression of GL2 and VLN1 in root hairs, and that inhibition of the GL2-VLN1 pathway leads to a longer growing time and increased root hair length (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Working model of GL2 and VLN in root hair growth and in response to osmotic stress in Arabidopsis. Arrows represent positive regulation and barred ends indicate inhibitory action. GL2 directly suppresses RSL2, LRL1, and LRL2 (Lin et al., 2015), and VLN4 organizes longer actin filaments in the shank and shorter actin filaments in the subapex and apex in the fast-growing phase to promote root hair growth rate (Zhang et al., 2011). Our results indicate that GL2 directly actives VLN1 transcription to promote actin filament bundling in the subapex and apex in the terminating-growth and fully grown phases, which inhibits root hair fast growth (shown in the dashed box). Osmotic stress blocks the GL2-VLN1 pathway, leading to significantly longer root hairs in Arabidopsis.

DISCUSSION

Root hair growth has broad implications for plant growth, development, and stress management. Based on the essential role of subapical and apical fine actin bundles in root hair cell fast elongation (Miller et al., 1999; Ketelaar et al., 2002; He et al., 2006; Pei et al., 2012), we revealed a key actin-bundling protein, VLN1, in root hair growth and the GL2-regulated VLN1 pathway. This pathway is crucial in the root hair response to osmotic stress, and the findings presented here represent an important step toward understanding the transcriptional regulation mechanisms of ABPs in cell elongation and the root hair response to environmental signals.

VLN1 Is Required for Bundling Apical and Actin Filaments in Root Hair Growth

Numerous ABPs have been identified in root hair development and growth (Ramachandran et al., 2000; Tominaga et al., 2000; Dong et al., 2001; McKinney et al., 2001; Mathur et al., 2003a, 2003b; Ketelaar et al., 2004; Yi et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2011; Bascom et al., 2018). However, ABPs that function in forming subapical and apical thick bundles, representing a key step in terminating root hair growth, remain to be identified. Among ABPs, VLNs have a high capacity for actin filament bundling and are thus expected to regulate subapical and apical actin filament bundling in root hair growth (Ketelaar et al., 2002; Pei et al., 2012). All Arabidopsis VLN family proteins (VLN1–VLN5) possess actin filament-bundling activities in vitro (Huang et al., 2005; Khurana et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010, 2011; Bao et al., 2012; Zou et al., 2019), and bundling roles of VLN2 to VLN5 have been demonstrated in vivo by observation of actin filament dynamics in individual mutants (Zhang et al., 2010, 2011; Bao et al., 2012; van der Honing et al., 2012). However, no VLNs have previously been identified to function in bundling subapical and apical thick actin filaments in root hair growth. Here, we found that VLN1 decorated long and bright filaments in the apical and subapical area (Fig. 2), which is considerably different from other published VLNs that express no filaments in this area of root hairs (e.g. VLN3; van der Honing et al., 2012) or very short filaments in apical and subapical areas in pollen tubes (e.g. VLN2 and VLN5; Qu et al., 2013). Additionally, VLN1 loss of function resulted in defects in the apical and subapical thick bundles and bundling processes as shown by directly observing dynamic behaviors of individual actin filaments using live-cell imaging (Figs. 3 and 4). Therefore, our results demonstrate that VLN1, similar to other VLNs, functions as an actin filament-bundling factor in vivo, and also that among VLNs, VLN1 acts as a major bundler in the subapex and apex of root hairs in Arabidopsis.

VLN1, unlike other VLNs, exhibited bundling activity only in a Ca2+-independent fashion in vitro (Huang et al., 2005), indicating that the biochemical property of VLN1 is suitable for hair growth in the slow/termination phase, during which defects in the high tip Ca2+ concentration are observed (He et al., 2006). Together with the root hair-growth phenotypes associated with various VLN1 genotypes (Fig. 1) and the outcomes of pharmacological experiments (Fig. 5), our results show that VLN1 is required for bundling subapical and apical actin filaments to form thick bundles in root hair growth. Given the role of subapical and apical fine actin bundles in delivering vesicles, preventing the forward movement of organelles, and maintaining nuclear location during fast cell elongation (Miller et al., 1999; Ketelaar et al., 2002, 2003; Pei et al., 2012) and the implication of VLNs in regulating vesicle delivery and maintaining nuclear location (Tominaga et al., 2000; Ketelaar et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2011; Pei et al., 2012), the role of VLN1-mediated thick bundles may be to block processes, such as those mentioned above, during the root hair fast-growing phase.

vln4 mutants show shorter root hairs with a significantly lower growth rate in the fast-growing phase, illustrating that VLN4 plays a major role in the fast-growing phase by organizing/maintaining longer actin filaments in the shank and shorter actin filaments in the subapex and apex in root hairs (Zhang et al., 2011). Our results show that VLN1 mainly functions in terminating-growth and fully grown phases in root hair growth by organizing thick bundles in the subapex and apex. We also noticed that VLN1 loss of function results in defects in thick bundles in the shank of root hairs (Supplemental Fig. S5) and a slightly slower growth rate in the fast-growing phase (Fig. 1); however, these phenotypes were more significant in vln4 than in vln1 (Fig. 1; Zhang et al., 2011), suggesting that VLN1 might assist VLN4 in bundling actin filaments in the shank during the fast-growing phase.

GL2 Directly Regulates VLN1 in Root Hair Growth

Transcription factors targeting cytoskeleton-binding proteins are key for managing plant growth and environmental stress tolerance (Wang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015). Given that some important transcription factors have been identified in root hairs (Libault et al., 2010; Yi et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2015), distinct pathways of transcription factor-mediated ABPs would fulfill the critical role of root hairs to respond to multiple growth, developmental, and environmental signals. However, the mechanisms by which transcription factors mediate ABPs for root hair growth are unknown. Transcription factor GL2 is crucial in root hair formation by inhibiting the bHLH transcription factor RHD6 and increasing expression of TRY, TG2, and ICE1 (Bruex et al., 2012; Simon et al., 2013). GL2 also functions in root hair growth by inhibiting expression of RSL2, LRL1, and LRL2 (Lin et al., 2015). Additionally, GL2 directly and positively regulates expression of the xyloglucan endotransglycosylase gene XTH17 in root cells to regulate root hair development (Tominaga-Wada et al., 2009). Similar to the positive role of Gl2 in XTH17 expression, our results demonstrate that Gl2 positively regulates VLN1 expression in root hairs by binding to the VLN1 promoter (Fig. 9). Additionally, genetic and actin dynamics evidence confirmed that GL2 participates in root hair growth by regulating VLN1 at the transcriptional level to control its bundling function on actin filaments (Figs. 6–9), revealing a regulatory mechanism of GL2 in root hair growth.

We also noticed that the genetic analysis showed different roles for GL2 and VLN1 in determining growth rate in the fast-growing phase (Figs. 1 and 6). Given the set of genes regulated by GL2 (Lin et al., 2015), this may indicate that GL2 recognizes other proteins, such as RSL2, LRL1, and LRL2, in the fast-growing phase of root hairs, suggesting that GL2 precisely regulates target proteins in root hair growth. Regardless, our results support that VLN1 is a main target of GL2 in root hair growth. Additionally, we noted that vln1 mutants and VLN1 OE seedlings showed more and fewer root hairs, respectively (Fig. 1), associated with the negative role of GL2 in root hair formation, suggesting that VLN1 might be involved in root hair formation mediated by GL2. However, organizing the actin dynamics in root hair formation is complex. Therefore, future studies are planned to identify whether GL2 is involved in actin filament dynamics in root hair formation by mediating VLN1 transcription.

The GL2-VLN1 Pathway Is Important for Root Hair Growth Response to Osmotic Stress

Root hair growth is very important in plant responses to water and nutrient deficiencies. Detailed observations in barley (Hordeum vulgare) showed that drought-induced root hair growth was much more significant in the late treatment period (a period when root hairs almost stop growing under normal conditions), indicating that drought-induced root hair growth largely depends on a longer fast-growing time (He et al., 2015). A similar longer fast-growing time was also observed in low phosphorus-induced root hair growth (Bates and Lynch, 1996). Here, we found that the expression of GL2 and VLN1 in root hairs is inhibited by osmotic stress, and that GL2 OE, VLN1 OE, and gl2 VLN1 OE seedlings display shorter hair growing times under osmotic stress, whereas the corresponding single and double mutants show contrasting results (Fig. 10). These results are consistent with the working model that osmotic stress inhibits the GL2-VLN1 pathway, which results in longer hair growing time and longer hairs (Fig. 11).

Investigating the transcriptional mechanisms of ABPs in root hair growth is an underexplored field of plant cell biology. In nature, shortages of water and nutrients represent major problems for crop yield stability. Understanding the transcriptional mechanisms regulating root hair growth and senescence might generate new ways to improve crops facing environmental and societal challenges. Here, we illustrated an important pathway in root hair growth, whereby transcription factor GL2 regulates actin-bundling protein VLN1, which in turn regulates cell tip growth as part of an environmental signal response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth Conditions and the Measurement of Growth Status

All Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants described in this study are in the Columbia background. vln1-1 and vln1-2 mutant plants were isolated from the seed stocks of the SALK_020027 and SALK_133579c lines, respectively. Seeds were incubated at 4°C for 3 d and then plants were grown until the observation time in normal experimental conditions, or grown for 3 d and then transferred to 0, 200, 250, and 300 mm mannitol treatments in osmotic stress experiments. Plants were grown in one-half strength MS medium with 0.8% (w/v) agar and 1.5% (w/v) Suc (pH 5.8) and vertically placed in a growth chamber at 22°C under long-day conditions (16-h-light/8-h-dark). To examine plant growth, seeds were grown in soil under normal conditions in a greenhouse (22°C) until 12-d-old seedlings were obtained. Leaf area, dry weight, and water content were measured in at least 60 of these plants, with three technical and biological replicates. Leaf area was the average of all rosette leaves per plant. Dry weight was measured in seedlings treated for 16 h in an 80°C oven. Water content was calculated as (fresh weight − dry weight)/plant. The relative dry weight and relative water content were counted by comparing seedlings from various genotypes with Col-0 seedlings.

Plasmid Construction and Plant Transformation

For the 35S::VLN1 plasmid, the VLN1 coding sequence fragment was cloned into the pCAMBIA1300-221 vector. The 1,587-bp promoter region, which contains the first intron of VLN1 and the VLN1 coding-sequence fragment, were cloned to generate the VLN1 promoter (pVLN1)::VLN1, the pVLN1::VLN1-GFP construct in the pSupper 1300, and the pVLN1::GUS construct in the pCAMBIA1300-221 vector. Primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplemental Table S6. All plasmids were introduced into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, then 35S::VLN1 and pVLN1::GUS were transformed into Arabidopsis Col-0 and pVLN1::VLN1 and pVLN1::VLN1-GFP were transformed into vln1-2 using the floral dip method to generate transgenic plants. All transgenic plants were selected on one-half strength MS medium supplied with hygromycin for homozygotes.

Root Hair Growth Analysis

Root hair length was observed for root hairs of 6-d-old seedlings located between 0 and 4 mm and between 2 and 4 mm from the primary root tip in normal-condition and osmotic stress experiments, respectively. The rate of root hair growth was observed in 3-d-old seedling root hairs at the bulges for 12 h at 1-h intervals using a stereomicroscope (SMZ-168, MOTIC) with a Moticam 2206 Microscope imaging system with a 1.5× objective lens for root hair length and a 2.0× objective lens for root hair growth rate. The onset of the terminating-growth phase in the root hair was defined as the first hour of a significant and sustained decline in growth rate and was used also to assess statistical significance compared to the growth rate of the previous hour (Supplemental Tables S1–S5). The beginning of the fully grown phase was defined as the first hour of growth rate that was maintained at <5 μm h−1. For pharmacological experiments, the 3-d-old seedlings were treated, or not, with 0.2 and 0.4 μm of the actin-disrupting drug LatA for 3 h followed by washes to remove the drug. Then, the seedlings either were removed to drug-free media to grow for 3 d before observing root hair length or were observed immediately for root hair growth rate. Seedling images were analyzed with ImageJ to measure the length of root hairs in the same focal plane. For these parameters, root hair length and growth rate were measured in >500 root hairs and >100 root hairs, respectively, from 30 individual seedlings per genotype.

Root Hair RNA Isolation and Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA in root hairs was isolated using methods described previously (Becker et al., 2014; Hirano et al., 2018). Briefly, surface-sterilized seeds were sown on a 3-cm-diameter cellophane disc placed on one-half strength MS medium for 6 d at 22°C under long-day conditions. The plants on the discs were then placed on an aluminum block and frozen by liquid nitrogen for 1 to 2 s. Next, care was taken to remove all plant tissues except root hairs using a brush. Total RNA of the retained root hairs was extracted using an RNA extraction buffer from the Easy Pure Plant RNA kit (Trans Poducts). Total complementary DNA was synthesized using the Omniscript Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen), and quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the Roche LightCycler 480. 18S rRNA gene was used as an internal control. Quantitative real-time PCR analyses were performed with three independent biological replicates. Primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S6. The histochemical GUS staining assay was performed using 4-d-old pVLN1::GUS transgenic seedlings in a 37°C incubator for 3 h. The images were taken using an upright microscope (Eclipse Ni-U, Nikon) with a Nikon DS-Ri2 microscope imaging system and a 20× objective lens.

ChIP-qPCR Assays

ChIP assays were performed according to a published protocol (Wang et al., 2015). Briefly, 2 to 4 g of 14-d-old HA-35SE-pGL2::GL2 (GL2 OE1) seedlings were fixed with 1% (v/v) formaldehyde under vacuum for 10 min. Chromatins were extracted and sonicated to generate DNA fragments with an average size of 500 bp. HA antibody (Abcam) plus Salmon sperm DNA/proteinA agarose (Upstate) were used to immunoprecipitate the protein-DNA complex, and the precipitated DNA was purified for qPCR analysis. Chromatin precipitated without antibody was used as a negative control, whereas the isolated chromatin before precipitation was used as an input control. Relative enrichment of a corresponding gene was normalized to the respective input DNA samples. The ChIP-qPCR assays were performed with three biological and technical replicates. Primers used for ChIP-qPCR are listed in Supplemental Table S6.

EMSA Assays

The GL2 promoter-driven VP16-GL2 N gene (Ohashi et al., 2003) was inserted into the region downstream of GST in the pGEX4T-1 vector. The resulting plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) and the transformed cells were cultured at 37°C for 16 h. The cultures were shaken for 4 h at 25°C with the addition of isopropylthio-β-galactoside (final concentration 1 mm). Then, the GST-tagged fusion proteins were purified as described previously (Ohashi et al., 2003). The EMSA assay was carried out using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (cataloge no. 20148, Thermo Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western Blot Assays

Ten-day-old seedlings carrying the pVLN1::VLN1–GFP gene were used for extracting protein. Protein samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE according to the previously described protocol (Liu et al., 2013). An anti-GFP antibody (Thermo Fisher) contained a dilution of 1:30,000 in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (50 mm Tris, 150 mm Na Cl, and 0.05% [v/v] Tween 20 [pH 7.5]) was used as a probe, followed by a dilution of 1:10,000 in a rabbit anti-mouse IgG H&L (horseradish peroxidase) secondary antibody (Abcam); then, the bands were detected by a Hypersensitive ECL Chemiluminescence Kit (Abcam). Rubisco bands were used as loading controls.

Quantitative Analysis of F-Actin Arrays

Three parameters, fluorescence intensity, skewness, and percentage of GFP signal occupancy, were employed to quantitatively analyze actin filament architecture (Li et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2015), correlating with the amount of actin filament, and the extent and density of actin filament bundling, respectively, in root hair images. Every root hair cell was documented with a series of overlapping micrographs. A fixed exposure time and gain setting were selected for vln1 mutants and their respective controls. Micrographs were analyzed in ImageJ using methods described previously (Li et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2015). For statistical analysis, fluorescence intensity, raw skewness, and density values were measured. For these measurements, at least 60 images of root hair cells were collected from at least 30 individual seedlings per genotype.

Time-Lapse Imaging of Signal F-Actin Dynamics

Time-lapse imaging of actin filament dynamics was preformed using the methods described previously (Zhang et al., 2015). Briefly, surface-sterilized seeds were sown on a coverslip on one-half strength MS medium and the coverslip was tilted in a petri dish, then the petri dish was placed horizontally for 4 d. Images of actin filaments were collected every 3 s by a spinning disk confocal microscope (Olympus) equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 spinning disk head. It was operated using the software MetaMorph (version 7.1, Molecular Devices). Other images of actin filaments were collected by laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon). Slice thickness was 0.5 μm and confocal z-stack images were made of 25 to 30 slices using a 100× oil immersion objective. Gain, pinhole, laser power, and detector offset were the same in all experiments. GFP was excited by a 488-nm laser, and the emitted fluorescence was collected using a 525/50-nm band-pass filter. Severing frequency (defined as the number of breaks per unit length per unit time [breaks mm−1 s−1]). The severing frequency was determined by counting all severing events from the filament at maximum length to its disappearance. The maximum filament length was determined by the longest length of a tracked filament during its growth and shrinking. Maximum filament life time was regarded as the elapsed time from the appearance of a filament to its disappearance. Filament depolymerization rate and elongation were calculated by Excel as changes in length among 1 s (Δlength/Δtime). We only take into account filaments that continuously grow or shrink for at least 10 s. We selected a 10 × 20-μm2 region that was 20 μm away from the tips of root hair cells to analyze bundling and debundling frequency. The dynamics of actin bundles in this region was tracked and analyzed for a consecutive 10 mins. The bundling and debundling frequencies were defined as the number of these events per unit area per unit time (events μm−2 s−1).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical significance calculations (except for microarray data) were made using SPSS statistical software; root hair length data were calculated by one-way ANOVA with a posthoc Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) mean-separation test and least significant difference (lsd) test at a significance level of P < 0.05. Significant difference was indicated by lowercase letters. Boxplots depicting root hair length in different genotypes or under different treatments were created using the methods described previously (Xing et al., 2017). Center lines in boxes represent the median with outer limits at the 25th and 75th percentiles. Notches indicate 95% confidence intervals; Altman whiskers extend to the 5th and the 95th percentiles, outliers are depicted as black dots, and the asterisk marks the sample mean. Other statistics (except for microarray data) were calculated by Student’s t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). In addition, all experiment charts were made by Graphpad Prism software.

Accession Numbers

The Arabidopsis Information Resource accession numbers for the sequences of the genes used in this study are as follows: AT1G79840 (GL2), AT2G29890 (VLN1), AT4G30160 (VLN4), AT1G66470 (RHD6), AT4G33880 (RSL2), AT2G24260 (LRL1), AT4G30980 (LRL2), and AT5G09810 (ACT7).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Molecular identification of different VLN1 genotypes.

Supplemental Figure S2. pVLN1::VLN1–GFP is functional.

Supplemental Figure S3. RT-PCR analysis of GL2 gene expression in Col-0, gl2-3, gl2-5, GL2 OE1, and gl2-1D seedlings.

Supplemental Figure S4. RT-PCR analysis of GL2 and VLN1 gene expression in Col-0, gl2 vln1-1, gl2 vln1-2, gl2 VLN1 OE1, and gl2 VLN1 OE2 seedlings.

Supplemental Figure S5. The actin filament configuration in root hairs of Col-0 and vln1-2.

Supplemental Table S1. Statistical significance analysis of current-hour growth rate compared to previous-hour growth rate in the different VLN1-genotype seedlings.

Supplemental Table S2. Statistical significance analysis of current-hour growth rate compared to previous-hour growth rate in the different GL2-genotype seedlings.

Supplemental Table S3. Statistical significance analysis of current-hour growth rate compared to previous-hour growth rate in the different GL2 and VLN1 double gene genotype seedlings.

Supplemental Table S4. Statistical significance analysis of current-hour growth rate compared to previous-hour growth rate in Col-0 seedlings under different mannitol treatments.

Supplemental Table S5. Statistical significance analysis of current-hour growth rate compared to previous-hour growth rate in the different GL2 and VLN1 double gene genotype seedlings under 300 mm mannitol treatment.

Supplemental Table S6. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Movie S1. Dynamics of single actin filaments in the subapical regions of Col-0 root hairs.

Supplemental Movie S2. Dynamics of single actin filaments in the subapical regions of vln1-2 root hairs.

Supplemental Movie S3. Dynamics of single actin filaments in the apical regions of Col-0 root hairs.

Supplemental Movie S4. Dynamics of single actin filaments in the apical regions of vln1-2 root hairs.

Supplemental Movie S5. Dynamics of single actin filaments in the subapical regions of gl2 root hairs.

Supplemental Movie S6. Dynamics of single actin filaments in the subapical regions of gl2 VLN1OE root hairs.

Supplemental Movie S7. Dynamics of single actin filaments in the apical regions of gl2 VLN1OE root hairs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shu-Cai Wang (Northeast Normal University) for providing the seeds of Arabidopsis gl2-3, gl2-1D, and GL2 OE1, Li-Jia Qu (Peking University) for providing the Arabidopsis gl2-5 seed, Tong-Lin Mao (China Agricultural University) for providing the vectors pCAMBIA1300-221 and pSupper1300, Xiao-Xue Wang (henyang Agricultural University) for providing the vector VP16, and Ming Yuan, Yi Wang, Dong-Lin Mao, andLei-Zhu (China Agricultural University) for their helpful comments on the article.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31500208 and 31470358), the Liaoning Education Foundation, the Hundred Thousand Ten Thousand Talent Project in Liaoning province, and in part by open funds of the State Key Laboratory of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry (grant no. SKLPPBKF1905).

References

- Bao C, Wang J, Zhang R, Zhang B, Zhang H, Zhou Y, Huang S(2012) Arabidopsis VILLIN2 and VILLIN3 act redundantly in sclerenchyma development via bundling of actin filaments. Plant J 71: 962–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bascom CS Jr., Hepler PK, Bezanilla M(2018) Interplay between ions, the cytoskeleton, and cell wall properties during tip growth. Plant Physiol 176: 28–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates TR, Lynch JP(1996) Stimulation of root hair elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana by low phosphorus availability. Plant Cell Environ 19: 529–538 [Google Scholar]

- Becker JD, Takeda S, Borges F, Dolan L, Feijó JA(2014) Transcriptional profiling of Arabidopsis root hairs and pollen defines an apical cell growth signature. BMC Plant Biol 14: 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruex A, Kainkaryam RM, Wieckowski Y, Kang YH, Bernhardt C, Xia Y, Zheng X, Wang JY, Lee MM, Benfey P, et al. (2012) A gene regulatory network for root epidermis cell differentiation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 8: e1002446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carol RJ, Dolan L(2002) Building a hair: Tip growth in Arabidopsis thaliana root hairs. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 357: 815–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan L, Duckett CM, Grierson C, Linstead P, Schneider K, Lawson E, Dean C, Poethig S, Roberts K(1994) Clonal relationships and cell patterning in the root epidermis of Arabidopsis. Development 120: 2465–2474 [Google Scholar]

- Dong CH, Kost B, Xia G, Chua NH(2001) Molecular identification and characterization of the Arabidopsis AtADF1, AtADFS and AtADF6 genes. Plant Mol Biol 45: 517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Q, Kita D, Li C, Cheung AY, Wu HM(2010) FERONIA receptor-like kinase regulates RHO GTPase signaling of root hair development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 17821–17826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Liu YM, Wang W, Li Y(2006) Distribution of G-actin is related to root hair growth of wheat. Ann Bot 98: 49–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Zeng J, Cao F, Ahmed IM, Zhang G, Vincze E, Wu F(2015) HvEXPB7, a novel β-expansin gene revealed by the root hair transcriptome of Tibetan wild barley, improves root hair growth under drought stress. J Exp Bot 66: 7405–7419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henty JL, Bledsoe SW, Khurana P, Meagher RB, Day B, Blanchoin L, Staiger CJ(2011) Arabidopsis actin depolymerizing factor4 modulates the stochastic dynamic behavior of actin filaments in the cortical array of epidermal cells. Plant Cell 23: 3711–3726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Konno H, Takeda S, Dolan L, Kato M, Aoyama T, Higaki T, Takigawa-Imamura H, Sato MH(2018) PtdIns(3,5)P2 mediates root hair shank hardening in Arabidopsis. Nat Plants 4: 888–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Robinson RC, Gao LY, Matsumoto T, Brunet A, Blanchoin L, Staiger CJ(2005) Arabidopsis VILLIN1 generates actin filament cables that are resistant to depolymerization. Plant Cell 17: 486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hülskamp M, Misŕa S, Jürgens G(1994) Genetic dissection of trichome cell development in Arabidopsis. Cell 76: 555–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YH, Kirik V, Hulskamp M, Nam KH, Hagely K, Lee MM, Schiefelbein J(2009) The MYB23 gene provides a positive feedback loop for cell fate specification in the Arabidopsis root epidermis. Plant Cell 21: 1080–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar T.(2013) The actin cytoskeleton in root hairs: All is fine at the tip. Curr Opin Plant Biol 16: 749–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar T, Allwood EG, Anthony R, Voigt B, Menzel D, Hussey PJ(2004) The actin-interacting protein AIP1 is essential for actin organization and plant development. Curr Biol 14: 145–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar T, de Ruijter NC, Emons AMC(2003) Unstable F-actin specifies the area and microtubule direction of cell expansion in Arabidopsis root hairs. Plant Cell 15: 285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar T, Faivre-Moskalenko C, Esseling JJ, de Ruijter NC, Grierson CS, Dogterom M, Emons AM(2002) Positioning of nuclei in Arabidopsis root hairs: An actin-regulated process of tip growth. Plant Cell 14: 2941–2955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana P, Henty JL, Huang S, Staiger AM, Blanchoin L, Staiger CJ(2010) Arabidopsis VILLIN1 and VILLIN3 have overlapping and distinct activities in actin bundle formation and turnover. Plant Cell 22: 2727–2748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahre U, Friederich E, Kost B, Louvard D, Chua NH(2000) Villin-like actin-binding proteins are expressed ubiquitously in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 122: 35–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM, Schiefelbein J(1999) WEREWOLF, a MYB-related protein in Arabidopsis, is a position-dependent regulator of epidermal cell patterning. Cell 99: 473–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM, Schiefelbein J(2002) Cell pattern in the Arabidopsis root epidermis determined by lateral inhibition with feedback. Plant Cell 14: 611–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Henty-Ridilla JL, Huang S, Wang X, Blanchoin L, Staiger CJ(2012) Capping protein modulates the dynamic behavior of actin filaments in response to phosphatidic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 3742–3754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Henty-Ridilla JL, Staiger BH, Day B, Staiger CJ(2015) Capping protein integrates multiple MAMP signalling pathways to modulate actin dynamics during plant innate immunity. Nat Commun 6: 7206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libault M, Brechenmacher L, Cheng J, Xu D, Stacey G(2010) Root hair systems biology. Trends Plant Sci 15: 641–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Ohashi Y, Kato M, Tsuge T, Gu H, Qu LJ, Aoyama T(2015) GLABRA2 directly suppresses basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor genes with diverse functions in root hair development. Plant Cell 27: 2894–2906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Qin T, Ma Q, Sun J, Liu Z, Yuan M, Mao T(2013) Light-regulated hypocotyl elongation involves proteasome-dependent degradation of the microtubule regulatory protein WDL3 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 1740–1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur J, Mathur N, Kernebeck B, Hülskamp M(2003a) Mutations in actin-related proteins 2 and 3 affect cell shape development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15: 1632–1645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur J, Mathur N, Kirik V, Kernebeck B, Srinivas BP, Hülskamp M(2003b) Arabidopsis CROOKED encodes for the smallest subunit of the ARP2/3 complex and controls cell shape by region specific fine F-actin formation. Development 130: 3137–3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney EC, Kandasamy MK, Meagher RB(2001) Small changes in the regulation of one Arabidopsis profilin isovariant, PRF1, alter seedling development. Plant Cell 13: 1179–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DD, De Ruijter NCA, Bisseling T, Emons AMC(1999) The role of actin in root hair morphogenesis: Studies with lipochito oligosaccharide as a growth stimulator and cytochalasin as an actin perturbing drug. Plant J 17: 141–154 [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi Y, Oka A, Rodrigues-Pousada R, Possenti M, Ruberti I, Morelli G, Aoyama T(2003) Modulation of phospholipid signaling by GLABRA2 in root-hair pattern formation. Science 300: 1427–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei W, Du F, Zhang Y, He T, Ren H(2012) Control of the actin cytoskeleton in root hair development. Plant Sci 187: 10–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesch M, Hülskamp M(2009) One, two, three...models for trichome patterning in Arabidopsis? Curr Opin Plant Biol 12: 587–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]