Abstract

Background.

Hypertension affects nearly 30% of the U.S. adult population. Due to the ubiquitous nature of mobile phone usage, text messaging offers a promising platform for interventions to assist in the management of chronic diseases including hypertension, including among populations that are historically underserved. We present the intervention development of Reach Out, a health behavior theory–based, mobile health intervention to reduce blood pressure among hypertensive patients evaluated in a safety net emergency department primarily caring for African Americans.

Aims.

To describe the process of designing and refining text messages currently being implemented in the Reach Out randomized controlled trial.

Method.

We used a five-step framework to develop the text messages used in Reach Out. These steps included literature review and community formative research, conception of a community-centered behavioral theoretical framework, draft of evidence-based text messages, community review, and revision based on community feedback and finalization.

Results.

The Reach Out development process drew from pertinent evidence that, combined with community feedback, guided the development of a community-centered health behavior theory framework that led to development of text messages. A total of 333 generic and segmented messages were created. Messages address dietary choices, physical activity, hypertension medication adherence, and blood pressure monitoring.

Discussion.

Our five-step framework is intended to inform future text-messaging-based health promotion efforts to address health issues in vulnerable populations.

Conclusion.

Text message–based health promotion programs should be developed in partnership with the local community to ensure acceptability and relevance.

Keywords: hypertension, African Americans, mobile health technology, race disparities, health equity

BACKGROUND

Hypertension is the most important modifiable cardiovascular risk factor (Cheng et al., 2014). African Americans are disproportionately affected by hypertension and the related diseases of stroke and cardiovascular disease (Nwankwo et al., 2013). The two most effective strategies to treat hypertension are (1) access and adherence to antihypertensive medications and (2) lifestyle modifications (increased physical activity, a diet high in fruits and vegetables and low in sodium) (Meschia et al., 2014). Currently, widespread adherence to these treatment strategies is low. Innovative approaches are necessary to encourage the adoption and maintenance of these behaviors.

Text-messaging interventions are a promising platform for managing a variety of chronic diseases. The ubiquitous nature of mobile phone usage allows text message–based health promotion to be particularly beneficial within difficult-to-reach populations (Pew Internet Research Project, n.d.). Other methods of health education, such as billboards or pamphlets, provide limited exposure in terms of audience and time. Text message–based interventions reduce the barrier of searching for health information (e.g., through websites) by providing relevant and salient information directly to the individual. Mobile health interventions, in which mobile devices are used to deploy interventions to improve health outcomes and include text messaging as well as health apps, also align with the Healthy People 2020 goals to expand innovative health communication and information technology (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.).

With regard to hypertension management, text message–based interventions are a feasible and acceptable method to improve medication adherence (Buis et al., 2015). However, few studies have evaluated text message–based programs promoting multiple hypertension reduction strategies. The Reach Out framework capitalizes on this gap in the literature by outlining the development of text messages focused on diet, physical activity, self-awareness of blood pressure, access to a primary care provider (PCP), as well as hypertension medication uptake and adherence. Despite published frameworks describing the development of mobile health interventions, there is limited insight into the community development of text message content (Abroms et al., 2015). Thus, we present the Reach Out text message design process to highlight the possibilities of a community-informed design process intended to serve a high risk and traditionally understudied population.

METHOD

Overview of Reach Out Behavioral Intervention

Reach Out is a health behavior theory–based, mobile health intervention to reduce blood pressure among hypertensive patients evaluated in a safety net emergency department primarily caring for African Americans. Reach Out will recruit hypertensive patients from a safety net emergency department in the urban, predominately African American community of Flint, Michigan. The Reach Out behavioral intervention consists of three text message–based components, each with two levels; healthy behavior text messaging (yes vs. no), prompted home blood pressure self-monitoring (weekly vs. daily), and facilitated PCP appointment scheduling with transportation (yes vs. no; see Table 1). After recruitment, participants will be randomized into one of eight experimental arms and receive the intervention for 12 months. Through this 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design, Reach Out will determine which combination and dose of the three behavioral intervention components contribute to a reduction in systolic blood pressure over the course of 1 year. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and Hurley Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

TABLE 1.

Reach Out Components

| Text message category | Levels | Segmenting variables | Mechanism for blood pressure (BP) reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy behavior: Diet, physical activity, medication adherence | Yes vs. No | No | - Decrease salt intake - Increase fruit and vegetable intake - Increase physical activity - Improve medication adherence |

| Healthy behavior: Change in blood pressure | Yes vs. No | - Medical provider - BP medication - BP control - BP compared with previous week (trend) |

- Discuss with provider - Improve medication adherence |

| Prompted blood pressure self-monitoring | Daily vs. Weekly | - BP control | - Participant activation - Participant autonomy - Participant competence |

| Facilitated provider and transportation scheduling | Yes vs. No | - Medical provider - BP control |

- Improve access to medical care |

Reach Out Academic and Community Partnership

Reach Out began as a community-based participatory research pilot intervention in African American churches (Skolarus et al., 2018). The academic partners included vascular neurologists and health behavior and health education experts. The community partners included Bridges into the Future, a community organization dedicated to the health and promotion, as well as members of the church health teams. We retain the partners from the pilot study and notably expanded to include emergency medicine providers and providers from the Flint community health clinic (CHC).

Reach Out Five-Step Framework

Our five-step framework for community-centered message development is included in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of Reach Out Message Design Process

DESIGN PROCESS

Step 1: Literature Review, Formative Community Research

An initial literature review was conducted, searching for key words: behavior change, mobile health, community, and hypertension. Identified articles were reviewed for methodology, theory, and text message design. To explore additional barriers and facilitators to healthy behaviors and text message preferences outside the original church population, we conducted 20 cognitive interviews with participants recruited from our partner CHC. The majority of participants were African American, women and on average, 40 years old.

Identified community barriers and facilitators to blood pressure self-management are included in Table 2 and text message preferences in Table 3. Overall, the formative research revealed a preference for shorter sentences, simpler vocabulary, and emoticon smiley faces. The inclusion of positive language without fear-based messaging and messages containing guidance instead of information alone were also preferred (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Common Facilitators and Barriers to Health Behaviors Identified by Community Members

| Category | Diet | Physical activity | Medication initiation and adherence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | - Food insecurity - Food knowledge - Cost - Stress - Negative influence of family and friends |

- Neighborhood safety - Knowledge - Cost - Time - Stress - Negative influence of family and friends |

- Cost - Side effects of antihypertensive - Taking more than one medication - Refilling medications - Language - Access to a primary care provider - Beliefs concerning medication - Remembering medications |

| Facilitators | - Desire to be healthy for loved ones (especially children or grandchildren) - To lose or maintain weight in pursuit of a desired physical appearance - Spiritual conviction through prayer - A belief in God and/or attendance at church - Dietary preferences: Boiled greens and baked chicken - Physical activity preferences: Basketball, football, and weightlifting |

||

TABLE 3.

Pilot Community Interview Feedback: Text Message Preferences

| Preference | Preferred example | Less preferred example |

|---|---|---|

| Information and direction vs. information alone | “Stress can make BP go up. Practice slow, deep breathing to relax. Exercise can also help you relax” | “Stress can make BP go up. Don’t let yourself get too stressed” |

| Concrete details vs. vague terms | “Use other spices instead of salt. Try pepper, garlic, or onions. This will cut down sodium. Your food will still be flavorful without all that salt!” | “Use other spices instead of salt. This will cut down sodium. Your food will still be flavorful without all that salt!” |

| Benefit-oriented messages vs. consequence-oriented messages | “Exercise helps prevent heart attack and stroke” | “If you don’t exercise, you have a higher chance of heart attack and stroke” |

| Encouraging language vs. discouraging language | “Try to” or “find exercise you enjoy” | “Try not to,” “don’t forget to,” “Limit your time” |

| Internal locus of control vs. external locus of control | “Maybe you don’t feel like you can do this, but guess what? YOU CAN! You are capable of making healthy choices, we promise” | “Making changes is hard. There are things in your life that are beyond your control that make it hard to change. Despite this, keep doing your best!” |

| Proper grammar vs. text slang | Going to the farmers’ market each week is a great way to find fresh and local fruits and veggies! | “Going 2 the farmer’s market is a gr8t way 2 find fresh and local fruits and veggies!” |

| We statements vs. I statements | “We are happy you take your blood pressure meds” | “I am happy that you take your blood pressure meds” |

Note. BP = blood pressure.

Step 2: Theoretical Framework Guiding Message Design

Social Cognitive Theory, Positive Affect, and Attribution Retraining.

Individuals change their behavior through a well-defined series of steps (Prochaska et al., 1992). Based on the results of our determinant analysis, we selected the social cognitive theory (SCT) to guide our message design. The SCT describes the complex interplay between behavioral, individual, and environmental factors. Collectively, these three factors help to determine the behaviors of individuals and populations. While certain unchangeable individual characteristics have an undeniable impact on an individual’s decisions, SCT asserts an individual can change and alter his or her environment (both built and social) to modify behaviors (Glanz et al., 2008). Though Reach Out is informed by all aspects of SCT, five key constructs influenced text message design: self-efficacy, social support, reinforcement, outcome expectations, and knowledge. See Table 4 for text message examples.

TABLE 4.

Sample Text Messages

| Text message category | Text message subcategory | Construct | Text message content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy behavior | Diet | Knowledge | Spicy food can be a great alternative to cooking with salt! Turn up the heat with jalapenos or chilis. But watch out for hot sauce which is often high in salt! |

| Diet | Reinforcement | Being busy can make changing your diet feel overwhelming. Try to take it one day at a time. One small step today is one more step towards reaching your goals! ☺ | |

| Physical activity | Outcome expectations | Getting up and moving your body everyday can help you lower your BP and make your meds work better! Try a walk or run today, you can do it! ☺ | |

| Physical activity | Self-efficacy | Being more active is possible if you take it one step at a time! Choosing the stairs over the elevator is a great start. You can do it ☺ | |

| Medication | Social support | Your doctor has your best interest at heart when it comes to your meds! If you have concerns about cost or side effects, ask them! They’re on your team ☺ | |

| BP change feedback |

SBP > 130 DBP < 80 |

Great job with your bottom number! Your top number is lower this week. Your meds, diet and exercise are key to lowering your BP more! Keep it up ☺ | |

| Blood pressure self-monitoring | Weekly feedback | BP is SBP > 130 DBP > 80 |

Your BP is XXX/XXX. Both the top and bottom numbers are above normal this week. Keep working hard to lower your BP with meds, eating healthy and exercise ☺ |

| Monthly feedback |

BP in range of 130/80–179/119 |

Your most recent BP is above normal meaning that you have high blood pressure. Talking with a doctor, meds and eating healthy can all help lower your BP! | |

| Facilitated appointment and transportation | Passive appointment reminder | This is a reminder to make an appointment with your doctor to talk about your blood pressure. Call Hamilton if you need to find a doctor (810) 406–4246 |

Note. BP = blood pressure; SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure.

Self-efficacy.

Within SCT, self-efficacy is the extent to which people believe they are capable of performing specific behaviors in order to attain certain goals. Messages intended to improve participant self-efficacy were of critical importance. These messages included small tips and words of encouragement to make behavioral changes appear attainable.

Social support.

Another portion of messages highlight relevant, reliable sources of social support in the recipient’s community including their friends, family, primary care provider, pharmacist, and the Reach Out study team. Such support can help the individual engage in self-regulation, a process whereby a person monitors their behavior and adjusts accordingly to meet a particular goal (Glanz et al., 2008).

Reinforcement.

To encourage continuation of behavior change (or to provide another prompt for those contemplating change), some messages were written to reinforce positive steps taken by the individual. These reinforcement messages primarily took the form of praise for hard work, willingness to adapt, and encouragement to maintain an optimistic attitude.

Outcome expectations.

Messages regarding outcome expectations were written to support progressive thinking and to encourage recipients to consider how a behavior performed in the present will positively or negatively affect their future, in the short and long term.

Knowledge.

Finally, messages were written to provide knowledge necessary for successful behavior change. These messages included information about local resources as well as broad health advice such as low-sodium cooking strategies and in-home, exercise suggestions.

Attribution retraining and positive affect.

In addition to SCT, Reach Out text messages included attribution retraining and positive affect strategies(Kangovi & Asch, 2018). While participants may be motivated to change when their blood pressures are elevated, psychology notes some individuals may view this experience as a failure and subsequently resort to avoidant behavior (Kangovi & Asch, 2018). Attribution retraining and positive affect address the cognitive and emotional reactions evoked by failure, obstacles, and unpleasant experiences.

Attribution retraining focuses on the cognitive reaction to failure by identifying underlying, controllable causes of failure. By focusing on factors within the individual’s control, attribution retraining helps people to overcome sentiments of apathy or feelings of helplessness. In addition, by designing messages that elicit positive affect, the emotional reaction of the participant can be shifted from one of shame toward one of hopefulness and motivation to change (Charlson et al., 2013). These methodologies, in addition to SCT, were vital in ensuring message content did not leave recipients with feelings of judgment or low self-worth.

Message Segmentation.

Reach Out text messages were segmented to increase personal relevance and efficacy (Kreuter, 2003). Messages were segmented on participant’s blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, adherence to those medications, and whether they have a PCP whom they see regularly. Based on these parameters participants are sent individualized blood pressure feedback.

TEXT MESSAGE CONTENT

Step 3: Design Community-Centered

Text Messages

The Reach Out behavioral intervention consists of three components: healthy behavior, blood pressure self-monitoring prompts, and PCP appointment and transportation scheduling facilitation. The text message design process for these three components is described below and examples are included in Table 4.

Healthy Behavior Messages: Diet, Physical Activity, and Medication Adherence.

Healthy behavior text messages encourage hypertension self-management, including healthy diet, physical activity, and initiating and/or adhering to prescribed antihypertensive medications. Weekly encouragement messages are sent to both acknowledge participants progress made and to express our appreciation for their continued participation in the study. Participants receive a weekly blood pressure feedback message in which the current week’s blood pressure is compared to prior blood pressures. These messages are segmented based on whether a participant has a PCP, is prescribed antihypertensives, and is adherent to those medications.

Prompted Home Blood Pressure Self-Monitoring.

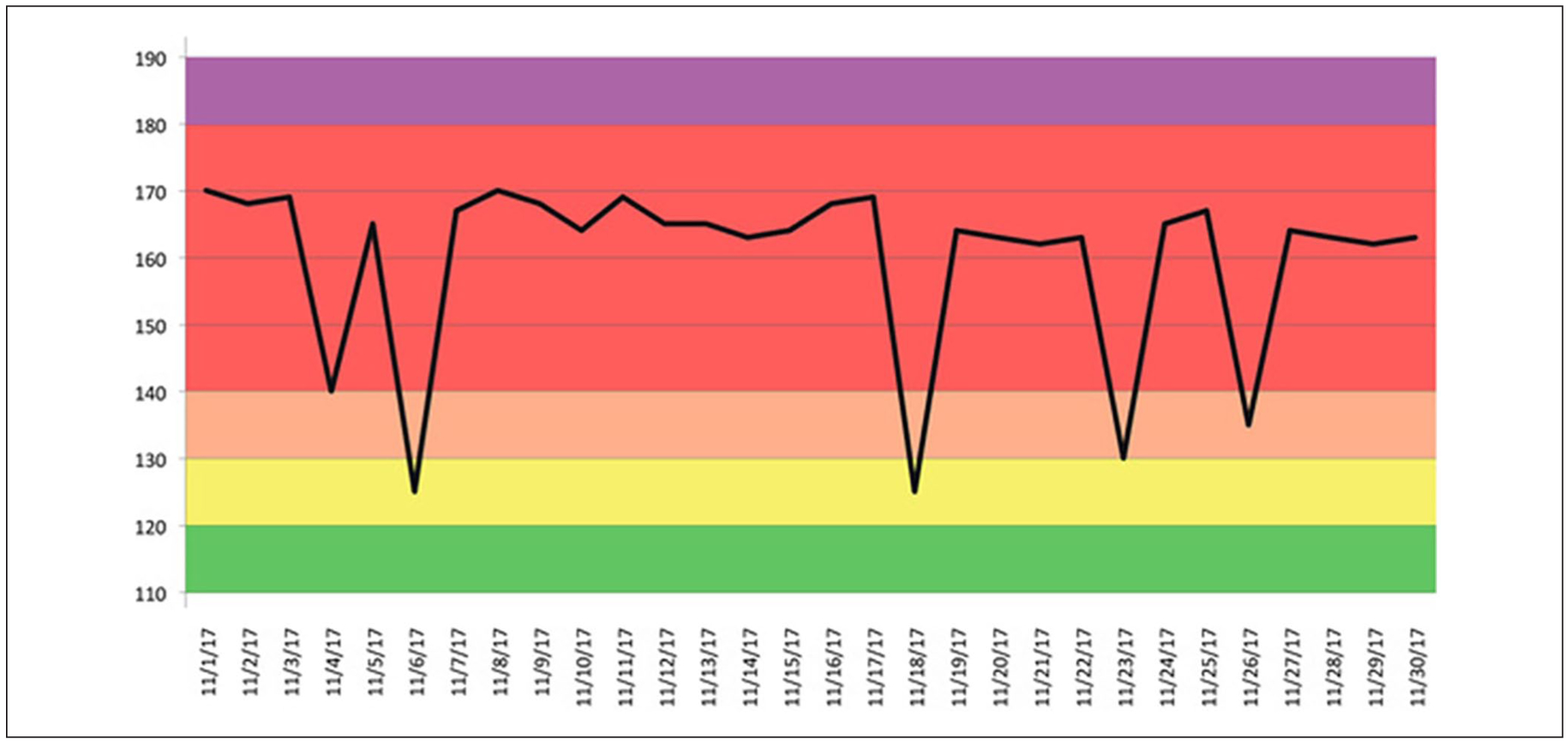

While all Reach Out participants are asked to take their blood pressure at home and text the reading back, the frequency of prompts (either daily or weekly) varies based on their respective randomization. Feedback about their blood pressure will be provided on a weekly basis addressing whether a participant’s blood pressure is above or below a predetermined threshold (130/80 mmHg; Cifu & Davis, 2017). Monthly blood pressure feedback will include a message describing where their individual measurement falls in relation to the 130 mmHg threshold and a picture message of a line graph depicting the participant’s systolic measurement trends throughout the study (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Final Blood Pressure Graph

Facilitated Appointment Scheduling.

Finally, participants randomized to receive facilitated PCP appointment scheduling and transportation will be sent personalized text messages with three possible provider appointment times and offered transportation via a third-party vendor.

Step 4: Community Review

To ensure text messages are relevant and acceptable to Flint residents, cognitive interviews were conducted with patients at a Flint CHC to evaluate a representative sample of messages. The “think-aloud” cognitive interview technique is particularly advantageous for community review because of its open-ended format, which minimizes interviewer-imposed bias (Beatty & Willis, 2007; Willis, 2004). Furthermore, the “think-aloud” method allows challenging language to be noted and revised to meet the literacy level of the population.

Community Feedback Procedures.

The interviews took place during normal clinic hours during May and June 2018. A total of 53 people participated typically before or after their clinic appointment. Participants were predominantly African American and over the age of 30 years. Interviews were generally 30 minutes in length, and all participants were compensated with $20. Participants were presented with 20 to 30 text messages to read out loud. Participants were then asked to answer several questions related to the message content including but not limited to, “What is your gut reaction to this message?,” “How do these messages apply to you?,” and “What changes would you make to these messages?.” The monthly blood pressure graph was also reviewed with participants.

Community Feedback Results.

The feedback was unanimously positive and revealed a high level of text message acceptability among Flint residents. Review of interview responses revealed the desire for messages to include more community-specific areas to exercise. Other feedback indicated many text messages focused on a younger population and missed the older demographic. Additionally, when multiple feedback points were addressed in the same text message, participants were typically only able to identify one piece of information. In review of the graph, confusion was noted in the multiple different colors.

Step 5: Revision Based on Community Feedback and Final Review

Incorporating Community Feedback.

Based on our community feedback to increase specificity, we added additional community-specific areas to exercise (i.e., high school track, local parks). In response to the request for additional focus on older adults, we added text messages geared toward participants with limited mobility (i.e., offering in-home exercises). We altered the sentence structure to include only one main informational point. We also simplified our graphs. The initial and final blood pressure graphs are included in Figures 2 and 3. The final graph uses only one color to indicate the normal range for blood pressure, as including other colors in the initial graph made the information difficult to interpret. Multiple colors can be misleading and make it difficult for patients to understand where their blood pressure actually falls (Waters et al., 2016). The dates were also changed to divide the horizontal axis into months of the year instead of individual dates for every submitted blood pressure reading. This allows the time frame measuring blood pressure to be better understood, as participants may more easily link spikes or drops in their blood pressure to a particular month and associated lifestyle factors influencing their blood pressure. Finally, the upper and lower bounds of blood pressure readings were expanded on the graph’s y-axis to be more inclusive of extreme measurements.

FIGURE 3.

Original Blood Pressure Graph

Final Review.

To ensure our community-centered message content was medically accurate, stroke neurologists, emergency medicine physicians, and experts in nutrition, pharmacy, and public health, reviewed the messages. The final Reach Out behavioral intervention includes 333 healthy behavior, blood pressure feedback and appointment scheduling text messages (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Total Number of Text Messages by Category

| Text message category | Text message subcategory | Total number of text messages |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy behavior | Diet | 138 |

| Physical activity | 132 | |

| Medication | 3 | |

| Blood pressure change feedback | 48 | |

| Blood pressure self-monitoring | Weekly feedback | 4 |

| Monthly feedback | 4 | |

| Facilitated appointment and transportation scheduling | Passive appointment reminder | 1 |

| Miscellaneous short codes and messages | Blood pressure reminder | 1 |

| Special codes | 2 |

We then created a text-messaging road map for each of our randomization groups outlining the text messages that would be received on a daily basis and changes in logic determined by individual segmentation variables. The logic behind these road maps was then built by a third-party into a text message delivery system which was tested by the Reach Out team. At the time of participant enrollment, participant’s phone numbers will be entered into this system to signal intervention initiation. Notably, our system uses short message services. These short message services ensure participants can receive text messages on any mobile phone, guaranteeing that participants do not need a smartphone to participate in Reach Out.

DISCUSSION

We used a community-partnered, health behavior theory–based approach to develop a set of segmented text messages focused on reducing blood pressure. Our messages were shaped by SCT, positive affect, and attribution retraining strategies. We used qualitative methods to ensure community and cultural relevance in an economically disadvantaged, predominately African American community. Collectively these steps allowed for the creation of the community-centered Reach Out text messaging system.

Value of Evidence-Based Health Promotion Programs

Reach Out combined SCT, positive affect, and attribution retraining to guide the message design process. SCT has been applied successfully in the development and implementation of past cardiovascular behavioral interventions (Ahn et al., 2014). Eliciting positive affect through health communications has improved adherence to antihypertensive medications among African Americans, (Ogedegbe et al., 2012) while a pilot study of attribution retraining showed promise in increasing physical activity among previously sedentary older adults (Sarkisian et al., 2005). The evidence available indicates SCT constructs, instigation of positive affect, and attribution retraining can all support difficult health behavior changes. Acknowledging that behavioral theories emphasize the importance of an individual making sustainable changes, Reach Out’s utilization of said theories offers the potential for participants to maintain reductions in their blood pressure even after the study ends.

Value of Community Feedback

Beyond drawing from theory, Reach Out demonstrates a commitment to gathering and incorporating community feedback in behavioral interventions. Reach Out embraces a collaborative approach between academia and the community; an approach that ensures the community is a part of the entire process. From its inception (Skolarus et al., 2018), the behavioral intervention was guided by the input and lived-experiences of the community, who will be most affected by the intervention. In doing so, Reach Out embraces the tenants of community-based participatory research by prioritizing the knowledge of community members and crafting the process around community expertise, needs, and goals (Israel et al., 1998; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). The cognitive interviews conducted in Flint reflect invaluable feedback that ensured Reach Out text messages met the needs and preferences of the community. The interviews also evaluated text message segmentation to ensure they were relevant to participants. This format promotes increased trust in the academic process and maximizes the potential impact of the intervention by improving the specificity of the text messages (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). When considering the Reach Out 5-step framework, the community formative research and review is included as a crucial component of the design process. In doing so, future programs can draw from the strong evidence-base of Reach Out to create sustainable, community partnerships and health promotion programs that best serve the population of interest.

Limitations

Mobile health reflects an emerging area of health care, research, and commercial business. Due to time constraints, we were unable to do a second community review to gather feedback about the changes we made. Given the changes were minor and community driven, we believe that residents would have found the changes appropriate. Finally, this type of intervention relies on a contracted third-party vendor to develop the technology to deliver the messages. The cost of this investment may prove too challenging for many public health organizations with limited resources to develop.

Implications for Practice

This step-by-step framework intends to inform future work in the mobile health space to promote linkages between communities, research and practice. Text message–based health promotion programs have the potential to change behavior and improve health outcomes, especially in high risk populations that are traditionally understudied. Partnering with the community during the development process is a health promotion strategy that can facilitate successful campaigns. Future health promotion efforts can use strategies like the text message segmentation and community review to advance the field of technology-based health promotion.

Mobile health programs for behavior change reflect opportunities to reach people in real time in a relevant, sustainable, and scalable manner for the long-term. The Reach Out 5-step framework can inform future text-messaging-based health promotion programs.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant (R01MD011516).

REFERENCES

- Abroms LC, Whittaker R, Free C, Mendel Van Alstyne J, & Schindler-Ruwisch JM (2015). Developing and pretesting a text messaging program for health behavior change: Recommended steps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 3(4), e107 10.2196/mhealth.4917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn S-H, Kim H-K, Kim KM, Yoon J-S, & Kwon JS (2014). Development of nutrition education program for consumers to reduce sodium intake applying the social cognitive theory: Based on focus group interviews. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition, 19(4), 342–360. 10.5720/kjcn.2014.19.4.342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty PC, & Willis GB (2007). Research synthesis: The practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opinion Quarterly, 71(2), 287–311. 10.1093/poq/nfm006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buis LR, Artinian NT, Schwiebert L, Yarandi H, & Levy PD (2015). Text messaging to improve hypertension medication adherence in African Americans: BPMED intervention development and study protocol. JMIR Research Protocols, 4(1), e1 10.2196/resprot.4040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Wells MT, Peterson JC, Boutin-Foster C, Ogedegbe GO, Mancuso CA, Hollenberg JP, Allegrante JP, Jobe J, & Isen AM (2013). Mediators and moderators of behavior change in patients with chronic cardiopulmonary disease: The impact of positive affect and self-affirmation. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 7–17. 10.1007/s13142-013-0241-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Claggett B, Correia AW, Shah AM, Gupta D, Skali H, Ni H, Rosamond WD, Heiss G, Folsom AR, Coresh J, & Solomon SD (2014). Temporal trends in the population attributable risk for cardiovascular disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation, 130(10), 820–828. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifu AS, & Davis AM (2017). Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults. JAMA Jounal of the American Medical Association, 318(21), 2132–2134. 10.1001/jama.2017.18706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K (2008). Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. 10.1146/annurev.publ-health.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangovi S, & Asch DA (2018). Behavioral phenotyping in health promotion: Embracing or avoiding failure. JAMA Jounal of the American Medical Association, 319(20), 2075–2076. 10.1001/jama.2018.2921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW (2003). Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. American Journal of Health Behavior, 27(Suppl. 3), S227–S232. 10.5993/AJHB.27.1.s3.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B, Braun LT, Bravata DM, Chaturvedi S, Creager MA, Eckel RH, Elkind MSV, Fornage M, Goldstein LB, Greenberg SM, Horvath SE, Iadecola C, Jauch EC, Moore WS, & Wilson JA (2014). Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke, 45(12), 3754–3832. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, & Gu Q (2013). Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012 (NCHS Data Brief No. 133). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db133.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogedegbe GO, Boutin-Foster C, Wells MT, Allegrante JP, Isen AM, Jobe JB, & Charlson ME (2012). A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(4), 322–326. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Internet Research Project. (n.d.). Mobile fact sheet. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/mobile-technology-fact-sheet/

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, & Norcross JC (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102–1114. 10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian CA, Prohaska TR, Wong MD, Hirsch S, & Mangione CM (2005). The relationship between expectations for aging and physical activity among older adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(10), 911–915. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0204.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolarus LE, Cowdery J, Dome M, Bailey S, Baek J, Byrd JB, Hartley SE, Valley SC, Saberi S, Wheeler NC, McDermott M, Hughes R, Shanmugasundaram K, Morgenstern LB, & Brown DL (2018). Reach out churches: A community-based participatory research pilot trial to assess the feasibility of a mobile health technology intervention to reduce blood pressure among African Americans. Health Promotion Practice, 19(4), 495–505. 10.1177/1524839917710893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Healthy People 2020. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=18

- Wallerstein N, & Duran B (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100(Suppl. 1), S40–S46. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters EA, Fagerlin A, & Zikmund-Fisher BJ (2016). Overcoming the Many Pitfalls of Communicating Risk In Diefenbach MA, Miller-Halegoua S, & Bowen DJ (Eds.), Handbook of Health Decision Science (pp. 265–277). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Willis GB (2004). Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Sage. [Google Scholar]