Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effects on common poststroke gait compensations of a soft wearable robot (exosuit) designed to assist the paretic limb during hemiparetic walking.

Design

A single-session cohort study of eight individuals in the chronic phase of stroke recovery was conducted. Two testing conditions were compared: walking with the exosuit powered versus walking with the exosuit unpowered. Each condition was eight minutes in duration.

Results

Compared to walking with the exosuit unpowered, walking with the exosuit powered resulted in reductions in hip hiking (27±6%, P= 0.004) and circumduction (20±5%, P= 0.004). A relationship between changes in knee flexion and changes in hip hiking was observed (Pearson r = −0.913, P< 0.001). Similarly, multivariate regression revealed that changes in knee flexion (β= −0.912, P= 0.007), but not ankle dorsiflexion (β= −0.194, P= 0.341), independently predicted changes in hip hiking (R2= 0.87, F(2, 4)= 13.48, P= 0.017).

Conclusions

Exosuit assistance of the paretic limb during walking is able to produce immediate changes in the kinematic strategy used to advance the paretic limb. Future work is necessary to determine how exosuit-induced reductions in paretic hip hiking and circumduction during gait training could be leveraged to facilitate more normal walking behavior during unassisted walking.

Keywords: gait, stroke, robotics, orthosis, compensation

INTRODUCTION

Gait dysfunction results from many types of neurological insult or injury, with stroke being among the most prominent. In fact, stroke is one of the leading causes of disability in America, with approximately 800,000 new cases every year1. Following recovery and rehabilitation, a large percentage of survivors of stroke are able to relearn to walk2, but most continue to have difficulty walking3. Hemiparetic gait is characterized by abnormal paretic limb kinematics and kinetics4. These impairments contribute to spatiotemporal asymmetries5–7 and gait compensations such as hip hiking and circumduction4,8–11, ultimately resulting in a slow, metabolically inefficient gait and an increased risk of falls6,12–16. Therefore, there is a need to investigate strategies for helping patients reduce their impairments and compensations.

Poststroke paresis of the ankle musculature results in an impaired ability to actively dorsiflex the foot during swing phase and generate positive plantarflexion power during the step-to-step transition17. These deficits impair two key subtasks of bipedal locomotion: ground clearance and forward propulsion. The standard of practice to treat poststroke ankle impairments is the ankle foot orthosis (AFO). While AFOs provide support to the ankle during swing, they have also been shown to reduce ankle push-off18 and reduce gait adaptability19. The development of wearable assistive technology that enhances the function of the paretic limb during both swing and stance phase is warranted.

An alternative to the passive support provided by an AFO is active assistance by a wearable robot. Our laboratory has built soft wearable robots (exosuits) to augment healthy walking20,21 and improve the mobility of individuals poststroke through facilitation of more normal paretic limb function during walking22 (see companion paper under revision23). Specifically, exosuits generate ankle plantarflexion forces during mid-to-late stance phase and generate ankle dorsiflexion forces during swing phase and initial contact. Exosuits differ from the current state-of-the-art exoskeletons in that they do not utilize a rigid structure or provide bodyweight support; rather, exosuits are lightweight and unobtrusive functional apparel designed to supplement existing joint abilities. Previously, we have shown that exosuits are capable of increasing ankle dorsiflexion during swing phase and forward propulsion generation by the paretic limb, ultimately reducing the energy cost of walking after stroke (see companion paper under revision23).

The goal of this study was to investigate the effects of exosuit assistance on common poststroke gait impairments and compensations. We hypothesized reduced hip hiking and circumduction and more symmetrical spatiotemporal gait parameters in persons in the chronic phase of stroke recovery walking with versus without exosuit assistance. Previous investigators have postulated that hip hiking and circumduction are secondary gait deviations used to achieve ground clearance during the paretic swing phase4,24,25. Thus, we also sought to test the hypothesis that reduced gait compensations would result from the effects that exosuit assistance would have on swing phase ankle dorsiflexion and knee flexion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enrollment and Assessment

The present study builds on our previous work by evaluating the effects of exosuit assistance on compensatory gait patterns23. Eight participants recruited from rehabilitation clinics in the greater Boston area participated in this study. Participant inclusion criteria included being between the ages of 25–75; at least six months post-stroke; able to walk for six minutes without stopping or needing the support of another individual; and have sufficient passive ankle range of motion, with the knee extended, to reach a neutral ankle angle (0°). Participant exclusion criteria included receiving Botox within the past six months, substantial knee recurvatum during walking, serious co-morbidities, an inability to communicate and/or be understood by investigators, a resting heart rate outside the range of 50–100 beats per minute or blood pressure outside the range of 90/60 to 200/110 mmHg, pain in the extremities or spine that limit walking, and experiencing more than 2 falls in the past month. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Medical clearance and signed informed consent forms approved by the Harvard University Human Subjects Review Board were obtained for all participants prior to data collection. This study conforms to all STROBE guidelines and reports the required information accordingly (see Supplementary Checklist).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| Participant | Side of Paresis | Sex | Age | Chronicity | Regular Orthosis | Regular Assistive Device | Treadmill Walking Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| y | y | m/s | |||||

| 1 | Right | F | 46 | 4.25 | None | None | 1.3^ |

| 2 | Right | M | 44 | 2.33 | None | None | 1.29 |

| *3 | Right | F | 30 | 7.08 | AFO | None | 1.05^ |

| 4 | Left | M | 67 | 3.33 | None | Cane | 0.81 |

| 5 | Left | M | 56 | 3.58 | None | None | 1.05 |

| 6 | Left | F | 52 | 0.75 | None | Cane | 0.53 |

| 7 | Left | M | 51 | 2.83 | AFO# | Cane | 0.93 |

| *8 | Left | F | 37 | 1.08 | AFO# | Cane | 0.67 |

Actual 10-meter overground walk test speeds were higher than used on treadmill. Participant #1’s actual overground speed was 1.72 m/s, but this speed was beyond the capabilities of the electromechanical actuator used for this study. Participant #3’s speed was 1.16 m/s, but this speed was not safe on the treadmill.

Lateral support needed (see Fig. 1).

Participant #7 typically used a foot-up brace. Participant #8 used a custom brace that supported frontal plane motion.

Experimental Design

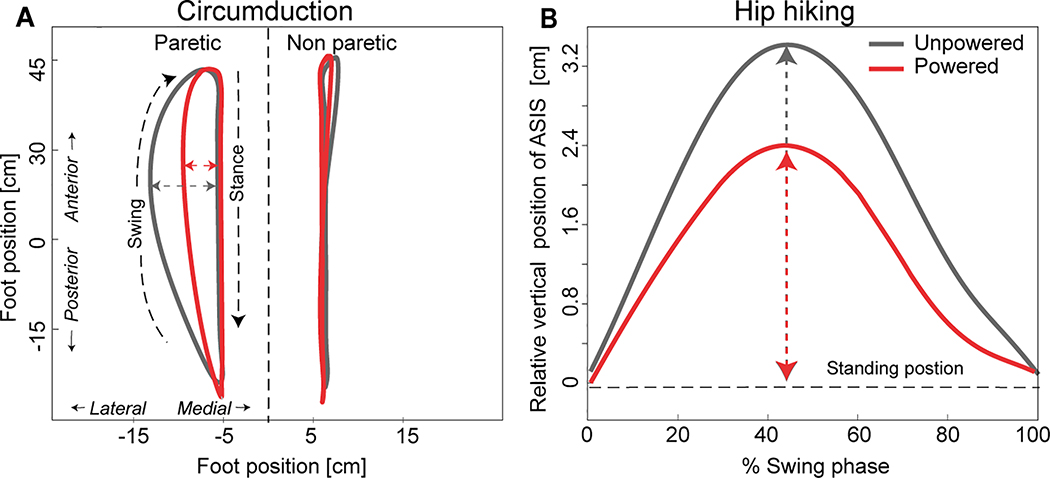

In brief, each participant completed two walking trials on an instrumented treadmill (Bertec, Columbus, OH, USA) while wearing an exosuit. Each trial was 8 minutes in length. The first trial consisted of walking with the exosuit unpowered and the second consisted of walking with the exosuit powered and transmitting assistive forces from an off-board actuation unit comprised of motors and a power supply22. The tethered exosuit transmitted forces generated by the actuation unit to the paretic limb, with the goal of assisting ankle plantarflexion during stance phase and ankle dorsiflexion during swing phase22 (also see companion paper under revision23). To evaluate our hypothesis that exosuit assistance would reduce poststroke gait compensations, we calculated two common metrics of compensation, circumduction and hip hiking (Fig 2), and compared their values during the unpowered and powered walking trials.

Figure 2:

Circumduction and hip hiking for a representative participant are shown during two walking conditions: the exosuit unpowered and powered. (A) The medial/lateral (x-axis) and posterior/anterior (y-axis) motion of the center of gravity (CoG) of the paretic and non-paretic foot during their respective gait cycles. Stance and swing phase are denoted. Circumduction is defined as the maximum lateral difference of the CoG during stance and swing phase. (B) Hip hiking was measured during the paretic limb’s swing phase (x-axis) as the difference between the vertical position of the paretic anterior superior illiac spine (ASIS) during walking and its position during quiet standing (y-axis). A y-axis value of “0” indicates that the ASIS position during walking was the same as the position during quiet standing. The maximum vertical position of the ASIS during the swing phase was used in the analyses.

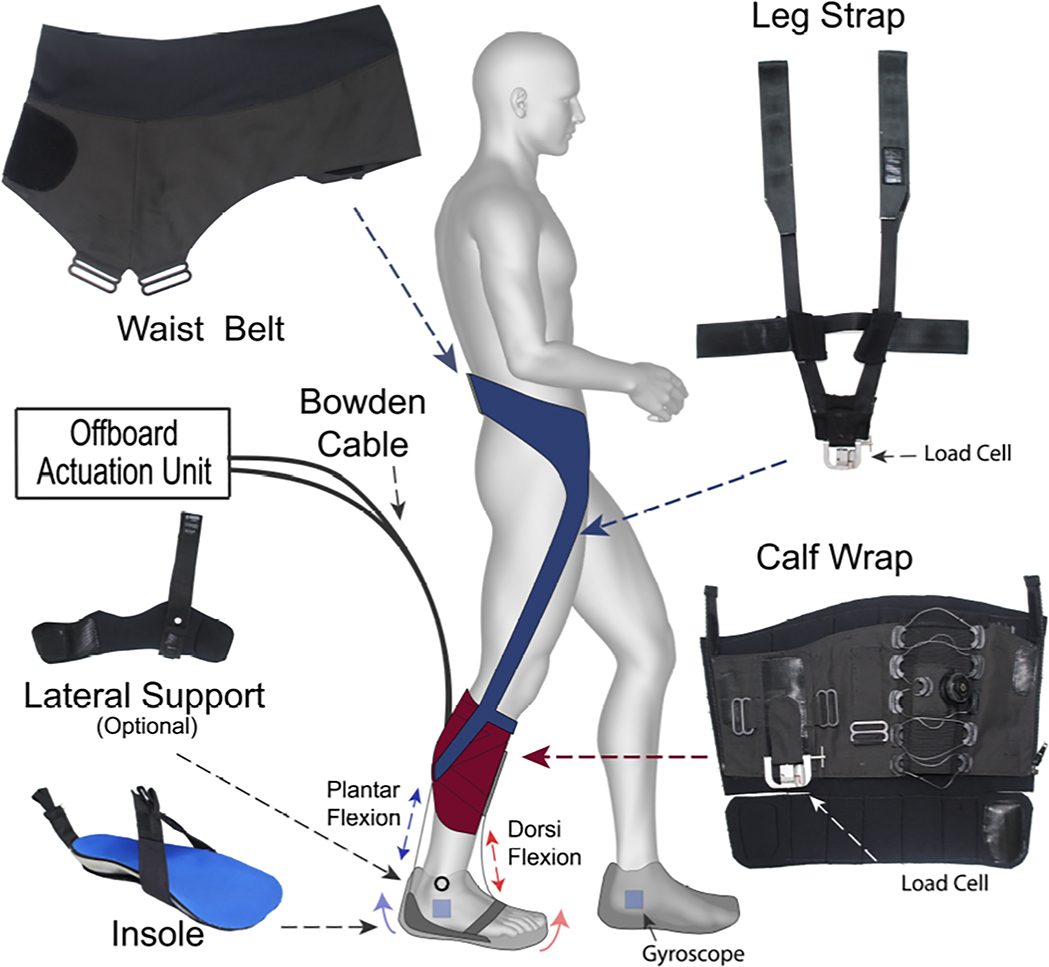

Exosuit Design and Control Strategy

The exosuit is a wearable robot comprised of garment-like, functional textiles that securely, yet comfortably, anchor to the body at the waist and paretic calf (Figure 1). A detailed overview of the exosuit design can be found in previous work from our laboratory20–22 (also see companion paper under revision23). The functional textile anchors interact with a low-profile insole located inside of the user’s shoe to generate assistive ankle torques through cable-based mechanical power transmission from a tethered actuation unit that generates mechanical power. Two Bowden cables travel from the actuation unit to the exosuit. One cable attaches anteriorly and provides dorsiflexion assistance when retracted by the actuation unit, and one attaches posteriorly and provides plantarflexion assistance when actuated. The components worn by the user have a total mass of approximately 0.90 kg, with the majority of this weight located above the knee. Gyroscope sensors mounted on the foot and force sensors mounted on the paretic shank are used in a control algorithm that determines gait events in real-time and controls the timing and amount of force delivered by the exosuit22 (also see companion paper under review23).

Figure 1:

An overview of the components of a unilateral soft wearable robot (exosuit). Functional textile anchors (waist belt, leg strap, calf wrap, and lateral support module) interact with an in-shoe insole to generate assistive ankle plantarflexion and dorsiflexion forces when the contractile elements of the exosuit (i.e., Bowden cables located adjacent to the ankle) are retracted by an off board actuation unit. The textile anchors integrate to make 2 modules that are active during different phases of the gait cycle. The waist belt and leg straps make up the plantarflexion module (blue), whereas the calf wrap forms the dorsiflexion module (red). Gyroscopes and load cells are used to detect gait events and measure the force being transmitted by the Bowden cables. These parameters serve as inputs in the exosuit’s control algorithm.

Clinical Evaluations

Each participant’s comfortable walking speed was evaluated overground using the 10-meter walk test (10MWT)26. Participants were allowed to use their regular assistive device (e.g., cane) if they typically used one for safety. The measured speed was then used as the input for treadmill walking speed. The 10MWT was also used to quantify each participant’s walking disability, and for the two participants who typically used an AFO, to evaluate their ability to safely walk without one—AFOs were not allowed during testing with the exosuit due to their restriction of ankle plantarflexion. For participants who, for safety, required the frontal plane support that is provided by an AFO, an optional exosuit module that passively controls for ankle inversion was used (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). All participants had the option to use a side-mounted handrail during treadmill walking; however, they were instructed to support themselves as minimally as possible.

Motion Analysis Evaluations

Three-dimensional gait analysis was performed during instrumented treadmill walking. A trained operator placed retroreflective markers on anatomical landmarks for use in motion capture analysis (VICON, Oxford Metrics, UK). The instrumented treadmill sampled ground reaction force data at 960 Hz and the motion capture system sampled marker position data at 120 Hz. In brief, markers were placed bilaterally over the first and fifth metatarsal heads, heel, distal shoe, medial and lateral malleoli, medial and lateral femoral condyles, greater trochanters, left and right anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS), left and right iliac crests, posterior superior iliac spines, and sacrum. Clusters of four markers were attached to the thighs and shanks of both legs. All markers and force trajectories were filtered using a zerolag, 4th order, low-pass, Butterworth filter with a 5–9 Hz optimal cut-off frequency selected using a custom residual analysis algorithm (MATLAB, The MathWorks Inc., USA). Joint angles were calculated using filtered marker data by means of an inverse kinematics approach (Visual 3D, C-Motion, Rockville, MD, USA). A kinematic gait event detection algorithm using the position of the heel and toe markers on the shoe was used to determine heel strikes and toe-off events.

Measuring Gait Compensations

To calculate circumduction, the center of gravity (CoG) of the foot taken from the link-segment model in Visual3D (C-Motion, Rockville, MD, USA) was used. The difference between the position of the CoG during stance phase and its maximum lateral displacement during swing phase defined the severity of circumduction (Fig. 2A)4,24. To calculate hip hiking, the vertical position of the ASIS marker calculated during quite standing was compared to the maximum vertical position during swing phase. Similar to previous work27, the difference in vertical position of the ASIS marker at these two points defined the severity of hip hiking (Fig. 2B). These variables were measured bilaterally. Due to obstructed markers during data collection for some individuals, the circumduction analyses included an N=8, the paretic hip hiking analyses included an N=7, and the nonparetic hip hiking analyses included an N=6.

Spatiotemporal measures were calculated using kinematic gait events. The temporal metrics calculated were: stance time, swing time, step time, and stride time. Temporal measurements were normalized by stride time and expressed as a percentage of the stride cycle. The spatial measurements calculated were: step length, step width, and stride length. Sagittal plane kinematics were used to quantify peak knee flexion and peak ankle dorsiflexion angles during swing phase for both the exosuit unpowered and powered conditions. For consistency across subjects, data from the first 30 strides recorded during the final minute of walking were used for generating all variables of interest.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS version 23. Unless otherwise indicated, inter-participant means and standard errors are reported. Paired t-tests were used to compare the exosuit unpowered and exosuit powered conditions at both the group and individual levels. Pearson correlation analyses measured the relationships between hip hiking, circumduction, swing phase peak knee flexion, and swing phase peak ankle dorsiflexion. Linear regression was subsequently used to determine the independent contribution of exosuit-induced changes in each ankle dorsiflexion and knee flexion to changes in each hip hiking and circumduction. An α ≤ 0.05 indicated significance.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Walking with the exosuit unpowered, participants showed, on average, paretic limb hip hiking of 3.65±0.77 cm and circumduction of 4.83±0.71 cm. On the non-paretic side, 0.69±0.17cm of hip hiking and 3.15±0.69 cm of circumduction were observed. Participants walked with a mean stride length of 1.16±0.07 m and stride time of 1.22±0.06 s. Paretic step length was 56±5 cm and step width was 16±1 cm. On the non-paretic side, step length and width were, respectively, 58±4 cm and 16±1 cm. Of the paretic gait cycle, participants spent 35±2 % in swing phase and 65±2 % in stance phase. Of the nonparetic gait cycle, 29±2 % was in swing phase and 71±2 % was in stance phase. During paretic swing phase, the peak flexion angle of the knee was 43.4±3.4° and the peak ankle dorsiflexion angle was −0.5±2.1° (i.e., the ankle was plantarflexed). During nonparetic swing phase, these values were, respectively, 60.9±2.6° and 1.7±1.9° for the knee and ankle.

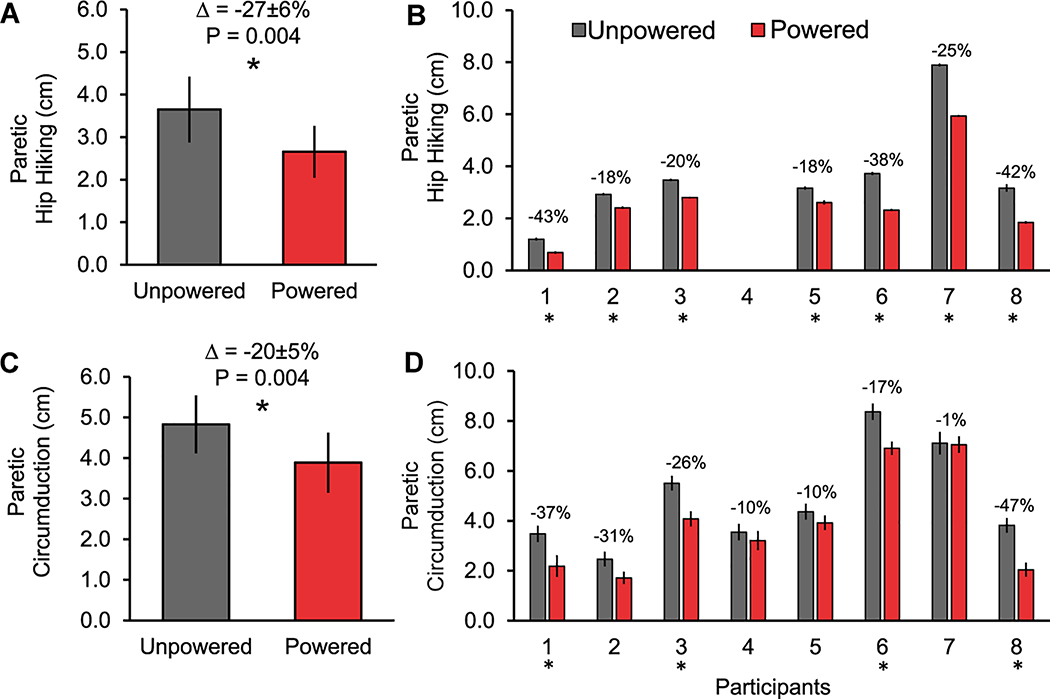

Reducing hip hiking and circumduction

Compared to walking with the exosuit unpowered, walking with the exosuit powered reduced hip hiking by an average 27±6% (P= 0.004) on the paretic side (Figure 3A). On the non-paretic side, changes in hip hiking between the powered and unpowered conditions were not observed (P= 0.935). Compared to walking with the exosuit unpowered, walking the exosuit powered reduced circumduction by an average 20±5% (P= 0.004) on the paretic side (Figure 3C). On the non-paretic side, changes in circumduction were not observed (P= 0.337). At the individual level, each participant presented with a significant decrease in paretic hip hiking (Figure 3B), circumduction (Figure 3D), or a reduction in both hip hiking and circumduction.

Figure 3:

Average±SE are presented for paretic limb hip hiking (A and B) and circumduction (C and D) during exosuit unpowered and powered walking conditions. Paired t-tests were conducted at the group and individual levels. For panels A (N=7) and C (N=8), a significant difference between the exosuit powered and unpowered conditions is indicated by an asterisk (*). For panels B (N=7) and D (N=8), an asterisk located under the participant’s number indicates a significant between-condition difference for that individual.

Spatiotemporal and kinematic changes

Examination of changes in spatiotemporal variables resulting from exosuit assistance revealed a significant increase (P= 0.002) in the nonparetic step length during the exosuit powered versus unpowered conditions (Table 2). Examination of ankle and knee kinematics revealed that only the peak ankle dorsiflexion angle during swing phase increased (P= 0.002) during the exosuit powered versus unpowered conditions (Table 3).

Table 2.

Spatiotemporal Parameters

| Unpowered | Powered | P | Unpowered | Powered | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swing time %GC | Step Length [m] | ||||||

| Paretic | 35.1(2.1) | 35.2(1.9) | 0.975 | Paretic | 0.56(0.05) | 0.57(0.05) | 0.612 |

| NonParetic | 29.3(1.5) | 29.5(1.4) | 0.376 | NonParetic | 0.58(0.04) | 0.60(0.04) | 0.002* |

| Stance time %GC | Step Width [m] | ||||||

| Paretic | 64.9(2.1) | 65.0(1.9) | 0.878 | Paretic | 0.16(0.01) | 0.15(0.01) | 0.092 |

| NonParetic | 70.8(1.5) | 70.6(1.4) | 0.433 | NonParetic | 0.16(0.01) | 0.14(0.01) | 0.136 |

| Step time %GC | Stride Length [m] | ||||||

| Paretic | 53.9(1.7) | 53.4(1.7) | 0.137 | 1.16(0.07) | 1.14(0.08) | 0.148 | |

| NonParetic | 46.1(1.7) | 46.6(1.7) | 0.137 | Stride Time [s] | |||

| 1.22(0.06) | 1.25(0.07) | 0.193 | |||||

Abbreviations: %GC- Percent Gait Cycle

Table 3.

Swing Phase Kinematic Parameters

| Unpowered | Powered | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak knee flexion (°) | |||

| Paretic | 43.36(3.42) | 44.98(3.58) | 0.323 |

| NonParetic | 60.86(2.64) | 60.85(1.97) | 0.994 |

| Peak dorsiflexion (°) | |||

| Paretic | -0.52(2.06) | 4.26(1.84) | 0.002* |

| NonParetic | 1.73(1.88) | 2.04(1.88) | 0.512 |

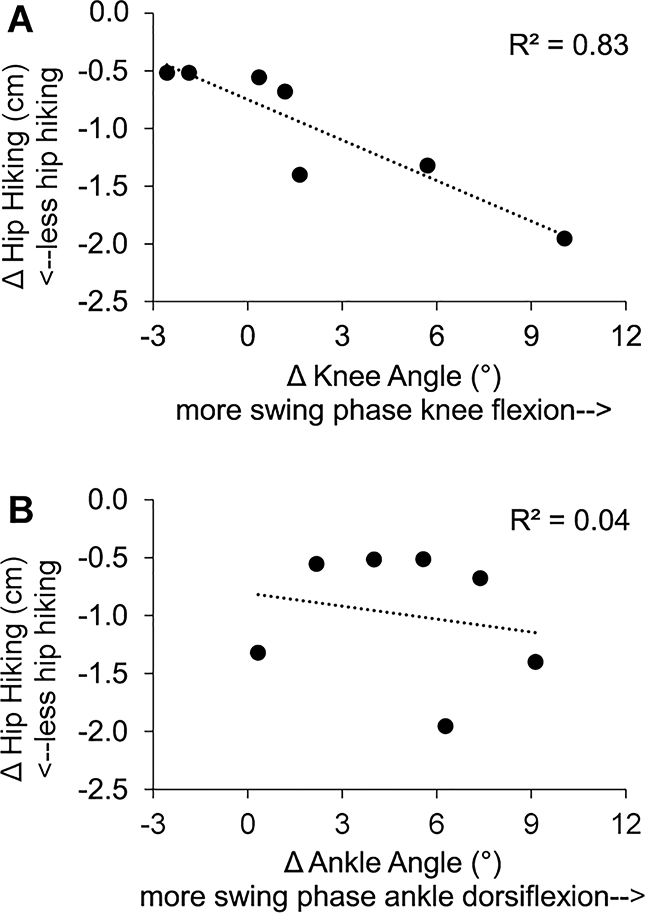

Kinematic contributors to reductions in hip hiking and circumduction

Bivariate correlation analyses of the relationships between changes in ankle dorsiflexion angle, knee flexion angle, circumduction, and hip hiking during swing phase revealed a relationship between only changes in knee flexion and changes in hip hiking (Pearson r = −0.913, P< 0.001, see Fig. 4). Similarly, a multivariate regression model evaluating the independent contribution of changes in each knee flexion and ankle dorsiflexion to changes in hip hiking revealed that changes in knee flexion (β= −0.912, P= 0.007), but not ankle dorsiflexion (β= −0.194, P= 0.341), independently predicted changes in hip hiking (R2= 0.87, F(2,4)= 13.48, P= 0.017). Exosuit-induced increases in swing phase knee flexion contributed to reductions in hip hiking during exosuit-assisted walking (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4:

(A) Relationship between changes in peak paretic knee flexion angle and changes in hip hiking during swing phase. (B) Relationship between changes in peak paretic ankle dorsiflexion angle and changes in hip hiking during swing phase.

DISCUSSION

Exosuits actively assist the paretic limb of individuals poststroke in a manner that reduces hip hiking and circumduction—abnormal kinematic strategies commonly observed during hemiparetic walking4. These findings extend our previous evaluation of the exosuit technology (see companion paper under revision23) and provide additional evidence that exosuits are a promising alternative to passive assistive devices (e.g., AFOs). The development of exosuits that can support ambulation by individuals after stroke in the clinic and the community is warranted.

For individuals poststroke, hip hiking and circumduction are believed to be kinematic compensations—versus the product of intrinsic neuromotor changes—for impaired ankle dorsiflexion and knee flexion during the swing phase4,8–11. Our findings of immediate reductions in both hip hiking and circumduction during exosuit-assisted walking support this hypothesis. That is, the rapid and substantial changes in the kinematic strategy used to advance the paretic limb during exosuit powered (versus unpowered) walking support the notion that paretic hip hiking and circumduction are, at least partially, secondary deviations compensating for deficits in paretic limb function, not primary impairments that need to be the direct targets of intervention. Further developments in the exosuit technology that allow direct assistance of knee and hip flexion may contribute to even greater reductions in frontal plane compensatory strategies, warranting investigation. That an exosuit acting to assist paretic limb propulsion and ankle dorsiflexion can have a substantial influence on a wearer’s overall walking pattern also speaks to the potential use of exosuits during gait retraining, especially during the early phases of stroke recovery before individuals adopt compensatory walking strategies.

Previous work studying the relationship between hip hiking and lower extremity joint impairments has demonstrated a strong link between hip hiking and deficits in ankle dorsiflexion, but not knee flexion12. Interestingly, we did not observe a relationship between exosuit-induced changes in ankle dorsiflexion and hip hiking; rather, changes in knee flexion strongly determined changes in hip hiking. Differences in experimental approach may explain these divergent findings. For example, the present study evaluates during treadmill walking the effects of an exosuit that provides active assistance of both ankle plantarflexion during stance phase and dorsiflexion during swing phase, whereas Cruz et al. evaluated the effects of a passive AFO during overground walking. Unlike an AFO, an exosuit’s assistance of ankle plantarflexion during late stance has the potential to increase paretic propulsion (see companion paper under review23) and accelerate the knee into flexion during swing phase28–30. Although our testing was conducted on a treadmill, it is important to note that treadmill biomechanical assessments have several advantages over overground assessments, including the ability to compute averages of a large number of consecutive strides and the ability to monitor and control walking speed. While future work is needed to directly evaluate differences in the effects produced by an AFO versus the exosuit technology during overground walking, our finding that exosuit assistance reduces compensatory kinematic behaviors during treadmill walking is important. Indeed, this finding speaks to the modifiability of non-desirable kinematic behaviors when deficits in key paretic limb biomechanical functions are targeted with a soft wearable robot. Moreover, given that treadmill walking is a popular gait training approach, reduced compensatory behaviors during treadmill walking may be desirable for gait rehabilitation.

Importantly, while exosuit assistance may be responsible for the reductions in hip hiking and circumduction observed, identifying the particular mechanisms responsible for these reductions is beyond the scope of this study. For example, given the multi-articular nature of the exosuit’s plantarflexion assistance module (see Figure 1), there is potential that the exosuit may generate forces about the knee (e.g., if the thigh connecting straps shift anterior or posterior to the knee joint, the exosuit would, respectively, generate a knee extension or flexion torque) concurrently with ankle PF. Further study is warranted to inform the design of future exosuit systems.

Poststroke gait impairment is heterogeneous and previous work has demonstrated that different compensatory strategies may be observed as a function of individuals’ level of walking disability25. Indeed, Stanhope et al. showed that among individuals in the chronic phase after stroke, slow walkers are more likely to employ hip hiking to achieve ground clearance, whereas fast walkers utilize circumduction. Despite our participants’ average walking speed being relatively fast (0.95 m/s), a broad range of speeds were recorded (from 0.53 to 1.30 m/s). Moreover, all participants had observable gait deficits and 5 of the 8 participants required regular use of an AFO or cane for community ambulation (see Table 1). Consistent with the findings of Stanhope et al, the fastest walker in our cohort (participant # 1) had the smallest magnitude of hip hiking when walking with the exosuit unpowered. Interestingly, though, this participant reduced both hip hiking (−43%) and circumduction (−37%) when walking with the exosuit powered. In contrast to the findings of Stanhope et al, the slowest walker in our cohort (participant # 6) presented with the largest magnitude of circumduction when walking with the exosuit unpowered; however, with the exosuit powered, he reduced hip hiking (−38%) by a greater magnitude than circumduction (−17%). Ultimately, the exosuit’s ability to reduce hip hiking, circumduction, and, in the case of four participants, both hip hiking and circumduction, is noteworthy and supports trialing the exosuit across the spectrum of disability among ambulatory individuals poststroke.

A recent study of high-intensity stepping training versus conventional gait interventions in individuals with subacute stroke reported substantial functional improvements in those receiving experimental training, but, also increased compensatory strategies31. While further study is needed to understand the negative consequences of these increased compensatory behaviors, they represent a deviation from the typical walking behavior that is the ultimate goal of gait rehabilitation. A potentially fruitful line of future research would be evaluating the potentially potent combination of high-intensity stepping training with gait-restorative wearable technology, such as the exosuit. This combination may maximize functional improvements while reducing gait compensations and facilitating the restoration of critical walking subtasks.

Limitations

The exploratory nature of the correlation and regression analyses employed with this small sample size is a potential limitation of this study and may explain why we were unable to identify a relationship between changes in ankle and knee function versus circumduction. Another limitation is that we did not randomize the order of testing, always testing the powered condition after the unpowered condition. This testing order was selected due to our previously reported finding that walking with an exosuit unpowered is comparable to walking without an exosuit worn23, as well as the potential for carryover effects following exosuit-assisted walking. Given the potential for carryover effects after exosuit-assisted walking, a random order of testing would require including a washout bout between conditions to minimize carryover to the unpowered condition. The addition of an additional bout of walking could have contributed to fatigue and an increase in compensatory behaviors during the unpowered condition, which could have inflated the positive effects observed.

Another potential limitation is that the exosuit unpowered condition may not be a true reflection of baseline performance; however, it is important to note that the worn elements of the exosuit are compliant, unobtrusive, and weigh less than a pair of pants. Indeed, our previous work demonstrates that wearing the exosuit unpowered does not influence poststroke propulsion or metabolic effort23, which suggests that the unpowered condition is comparable to walking with the exosuit unworn. Finally, although all participants studied presented with gait deficits and a majority required use of an AFO or assistive device for safe community ambulation, it should be noted that these participants had a higher than average walking speed for individuals poststroke (0.95 m/s). Future work is necessary to evaluate the effects of the exosuit on slower individuals, as well as to compare the effects of exosuit assistance to traditionally used braces.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Mr. Christopher Siviy, Mr. Fabricio Saucedo, and Mr. Stephen Allen and Ms. Jozefien Speeckaert for their assistance with data collection and processing. We thank Dr. Stefano De Rossi, Mr. Gabriel Greely, Ms. Tiffany Wong, Mr. Ye Ding, and Dr. Alan Asbeck for their assistance developing the exosuit.

Disclosures: Funding: This work was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), Warrior Web Program (Contract Number W911NF-14-C-0051). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressly or implied, of DARPA or the U.S. Government. This work was also partially funded by the National Science Foundation (CNS-1446464), American Heart Association (15POST25090068), National Institutes of Health (1KL2TR001411), Harvard University Star Family Challenge, Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, and Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Competing interests: Patents have been filed with the U.S. Patent Office describing the exosuit components documented in this manuscript. JB, KGH, and CJW were authors of those patents and patent applications. Harvard has entered into a licensing and collaboration agreement with ReWalk Robotics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, Ferranti S De, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update a report from the American Heart Association.; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrilli S, Nicolas B, Gallien P. Prognostic Factors in the Recovery of the Ability to Walk After Stroke. 2002;11(6):330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ada L, Dean CM, Hall JM, Bampton J, Crompton S, L AA, Cm D, Jm H, Bampton J. A Treadmill and Overground Walking Program Improves Walking in Persons Residing in the Community After Stroke : 2003;84(October):1486–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen G, Patten C, Kothari DH, Zajac FE. Gait differences between individuals with post-stroke hemiparesis and non-disabled controls at matched speeds. Gait and Posture. 2005;22(1):51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson KK, Parafianowicz I, Danells CJ, Closson V, Verrier MC, Staines WR, Black SE, McIlroy WE. Gait Asymmetry in Community-Ambulating Stroke Survivors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2008;89(2):304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Awad LN, Palmer JA, Pohlig RT, Binder-Macleod SA, Reisman DS. Walking speed and step length asymmetry modify the energy cost of walking after stroke. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2015;29(5):416–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen JL, Kautz SA, Neptune RR. Step length asymmetry is representative of compensatory mechanisms used in post-stroke hemiparetic walking. Gait & posture. 2011;33(4):538–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruz TH, Dhaher YY. Impact of ankle-foot-orthosis on frontal plane behaviors post-stroke. Gait and Posture. 2009;30(3):312–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerrigan DC, Frates EP, Rogan S, Riley PO. Hip hiking and circumduction: quantitative definitions. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists. 2000;79(3):247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmid S, Schweizer K, Romkes J, Lorenzetti S, Brunner R. Secondary gait deviations in patients with and without neurological involvement: A systematic review. Gait and Posture. 2013;37(4):480–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Susko T, Swaminathan K, Krebs HI. MIT-Skywalker: A Novel Gait Neurorehabilitation Robot for Stroke and Cerebral Palsy. IEEE transactions on neural systems and rehabilitation engineering : a publication of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2016;24(10):1089–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruz TH, Lewek MD, Dhaher YY. Biomechanical impairments and gait adaptations post-stroke: Multi-factorial associations. Journal of Biomechanics. 2009;42(11):1673–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farris DJ, Hampton A, Lewek MD, Sawicki GS. Revisiting the mechanics and energetics of walking in individuals with chronic hemiparesis following stroke: from individual limbs to lower limb joints. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2015;12(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neptune RR, Kautz SA, Zajac FE. Contributions of the individual ankle plantar flexors to support, forward progression and swing initiation during walking. Journal of biomechanics. 2001;34(11):1387–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reisman DS, Rudolph KS, Farquhar WB. Influence of speed on walking economy poststroke. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2009;23(6):529–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vistamehr A, Kautz SA, Bowden MG, Neptune RR. Correlations between measures of dynamic balance in individuals with post-stroke hemiparesis. Journal of biomechanics. 2016;49(3):396–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Awad LN, Binder-Macleod SA, Pohlig RT, Reisman DS. Paretic Propulsion and Trailing Limb Angle Are Key Determinants of Long-Distance Walking Function After Stroke. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2015;29(6):499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vistamehr A, Kautz SA, Neptune RR. The influence of solid ankle-foot-orthoses on forward propulsion and dynamic balance in healthy adults during walking. Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon). 2014;29(5):583–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Swigchem R, Roerdink M, Weerdesteyn V, Geurts AC, Daffertshofer A. The capacity to restore steady gait after a step modification is reduced in people with poststroke foot drop using an ankle-foot orthosis. Physical therapy. 2014;94(5):654–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panizzolo F, Galiana I, Asbeck A, Siviy C, Schmidt K, Holt K, Walsh C. A biologically-inspired multi-joint soft exosuit that can reduce the energy cost of loaded walking. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asbeck AT, De Rossi SMM, Holt KG, Walsh CJ. A biologically inspired soft exosuit for walking assistance. The International Journal of Robotics Research. 2015:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae J, De Rossi SMM, O’Donnell K, Hendron KLK, Awad LN, Teles Dos Santos TR, De Araujo VL, Ding Y, Holt KG, Ellis TD, Walsh CJ. A soft exosuit for patients with stroke: Feasibility study with a mobile off-board actuation unit. IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics. 2015;2015–Septe(August):131–138. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Awad LN, Bae J, O’Donnell K, De Rossi SMM, Hendron K, Allen S, Holt KG, Ellis TD, Walsh CJ. Soft Wearable Robots Improve Walking Function and Economy after Stroke. Science Translational Medicine. In Review. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerrigan DC, Frates EP, Rogan S, Riley PO. Hip hiking and circumduction: quantitative definitions. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists. 2000;79(3):247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanhope VA, Knarr BA, Reisman DS, Higginson JS. Frontal plane compensatory strategies associated with self-selected walking speed in individuals post-stroke. Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon). 2014;29(5):518–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Middleton A, Fritz SL, Lusardi M. Walking speed: the functional vital sign. Journal of aging and physical activity. 2015;23(2):314–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyrell CM, Roos MA, Rudolph KS, Reisman DS. Influence of systematic increases in treadmill walking speed on gait kinematics after stroke. Physical therapy. 2011;91(3):392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knarr BA, Kesar TM, Reisman DS, Binder-Macleod SA, Higginson JS. Changes in the activation and function of the ankle plantar flexor muscles due to gait retraining in chronic stroke survivors. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2013;10:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kesar TM, Perumal R, Reisman DS, Jancosko A, Rudolph KS, Higginson JS, Binder-Macleod SA. Functional electrical stimulation of ankle plantarflexor and dorsiflexor muscles: effects on poststroke gait. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40(12):3821–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zelik KE, Adamczyk PG. A unified perspective on ankle push-off in human walking. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 2016;219(23):3676–3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahtani GB, Kinnaird CR, Connolly M, Holleran CL, Hennessy PW, Woodward J, Brazg G, Roth EJ, Hornby TG. Altered Sagittal- and Frontal-Plane Kinematics Following High-Intensity Stepping Training Versus Conventional Interventions in Subacute Stroke. Physical therapy. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.