SUMMARY

The intestinal epithelium has a high cell turnover rate and is an excellent system to study stem cell-mediated adaptive growth. In the Drosophila midgut, the Ste20 kinase Misshapen, which is distally related to Hippo, has a niche function to restrict intestinal stem cell activity. We show here that, under low growth conditions, Misshapen is localized near the cytoplasmic membrane, is phosphorylated at the threonine 194 by the upstream kinase Tao, and is more active toward Warts, which in turn inhibits Yorkie. Ingestion of yeast particles causes a midgut distention and a reduction of Misshapen membrane association and activity. Moreover, Misshapen phosphorylation is regulated by the stiffness of cell culture substrate, changing of actin cytoskeleton, and ingestion of inert particles. These results together suggest that dynamic membrane association and Tao phosphorylation of Misshapen are steps that link the mechanosensing of intestinal stretching after food particle ingestion to control adaptive growth.

In Brief

Yeast is a natural food source for fruit flies, and accumulation of yeast particles in their midgut causes expansion of the gut tube. Li et al. show that such expansion triggers a mechanosensing mechanism leading to the relief of inhibition of Yorkie-mediated tissue growth by the upstream kinase Misshapen.

INTRODUCTION

The intestinal epithelium has a strong capacity of growth adaptation due to the high rate of cell loss and the presence of intestinal stem cell (ISC)-mediated regeneration. Even though multiple stem cell populations have been identified in the mammalian intestinal crypts, how the surrounding niche and the lumenal content affect stem cell activity is not fully understood (Demitrack and Samuelson, 2016; Tan and Barker, 2014; Tetteh et al., 2015).

In the adult Drosophila midgut, ISCs are the only mitotic cells under the normal growth condition and therefore provide a simpler but resourceful model to study stem cell-mediated homeostasis (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006). The evolutionarily conserved Delta-Notch signaling establishes the asymmetry during ISC division to generate a renewed ISC and a neighboring daughter cell called enteroblast (EB) or pre-enteroendocrine cell (pre-EE), which differentiates to become an enterocyte (EC) for nutrient absorption or an EE for hormone secretion, respectively (Biteau and Jasper, 2014; de Navascues et al., 2012; Goulas et al., 2012; Guo and Ohlstein, 2015; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2007; Perdigoto et al., 2011; Zeng and Hou, 2015). Conserved pathways including Wnt, BMP, Hedgehog, EGF, JAK-STAT, Insulin, TOR, and Hippo (Hpo) participate in the regulation of various aspects of ISC division and subsequent daughter cell differentiation for midgut homeostasis (Jiang et al., 2016; Lemaitre and Miguel-Aliaga, 2013; Li and Jasper, 2016; Naszai et al., 2015). The intestinal epithelial cells, including ECs, EBs, and EEs, as well as surrounding tissues such as trachea, neurons, muscles, and hemocytes, all produce diffusible ligands to regulate the above-mentioned pathways to modulate directly or indirectly the ISC activity (Amcheslavsky et al., 2014; Ayyaz et al., 2015; Chakrabarti et al., 2016; Cognigni et al., 2011; Cordero et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2009; Li et al., 2014; Li et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2008; O’Brien et al., 2011; Ren et al., 2010; Scopelliti et al., 2014; Tian and Jiang, 2014; Zhai et al., 2015). How these many cell types and regulatory pathways are coordinated to achieve appropriate intestinal homeostasis remains to be investigated.

We previously show a niche mechanism that depends on the Ste20 kinase Misshapen (Msn) (Li et al., 2014). In differentiating EBs, Msn activates Warts (Wts), thereby suppressing the activity of Yorkie (Yki) and the expression of the JAK-STAT pathway ligand Upd3 to restrict tissue growth (Figure 1A). Furthermore, the mammalian Msn homolog MAP4K4 also interacts with LATS to suppress YAP (Li et al., 2014). Other reports have similarly illustrated that the Ste20 kinases Hpo, Msn, and Happyhour (Hppy) of Drosophila, and their mammalian homologs Mst1/2, MAP4K4/6/7, and MAP4K1/2/3/5, respectively, have overlapping functions in regulating Wts/LATS and Yki/YAP in various assays (Li et al., 2015; Meng et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2015). Therefore, the Hpo pathway has been expanded to include the Hpo, Msn, and Hppy subfamilies of Ste20 kinases.

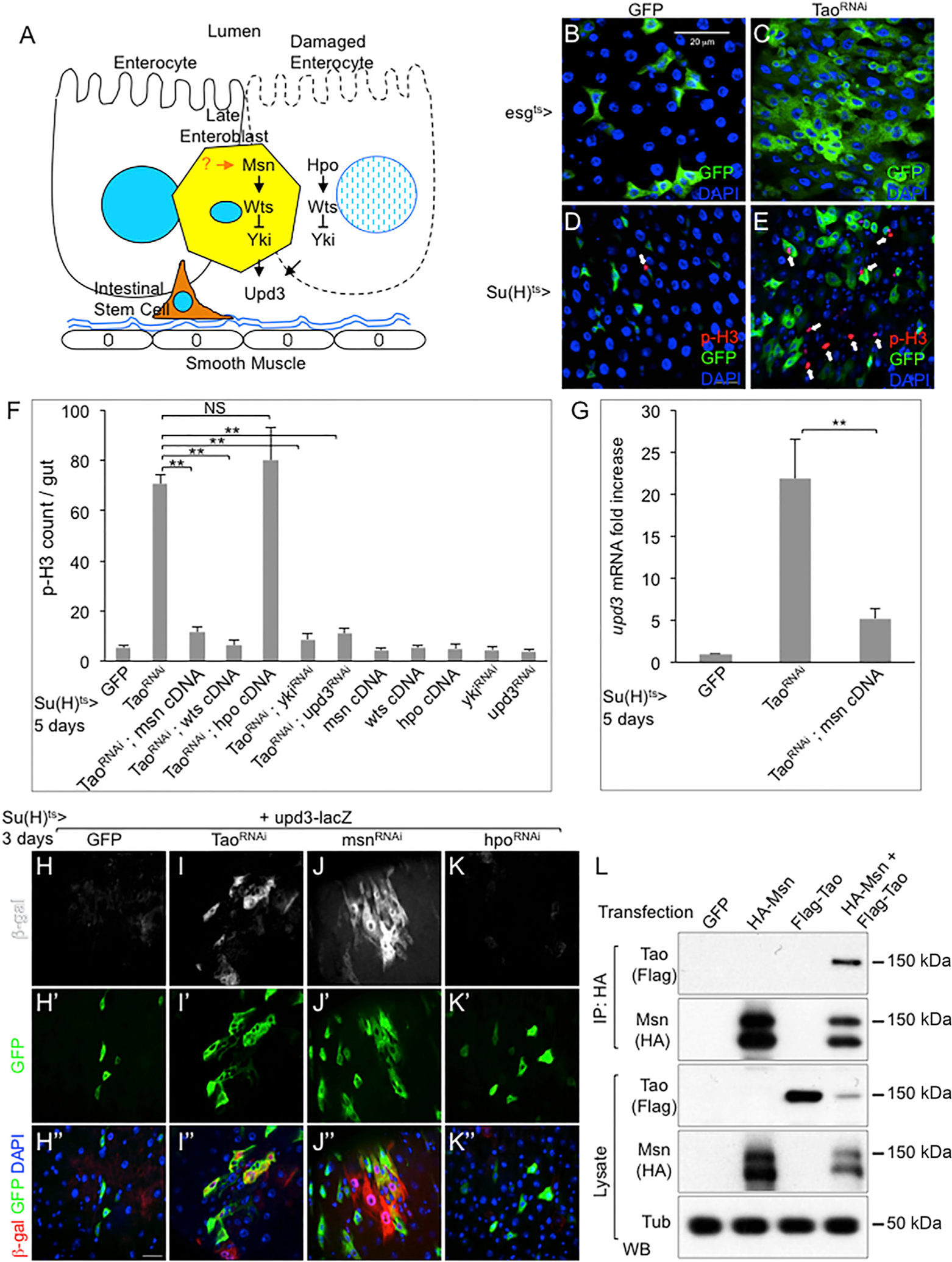

Figure 1. Tao Functions in the Msn-Wts-Yki Pathway.

(A) A model illustrating the function of Msn-Wts-Yki and Hpo-Wts-Yki pathways in EBs and ECs, respectively, to control Upd3 expression and adult midgut homeostasis. The physiological process that regulates Msn in EBs is the focus of this report.

(B–E) Confocal images of surface views of adult Drosophila midguts. The esgts>GFP and Su(H)ts>GFP as indicated were used as drivers to express Tao dsRNA. Female flies of 5–7 days old were shifted to 29°C for 5 days to inactivate Gal80ts to allow Gal4 to activate UAS-Tao dsRNA and UAS-GFP before gut dissection and analysis. Green is GFP, arrows point to red p-H3 staining for mitotic chromatin, blue is DAPI staining of nuclear DNA. (B) esgts>GFP driven control midgut.

(C) esgts>GFP driven TaoRNAi midgut. (D) Su(H)ts>GFP control midgut. (E) Su(H)ts>GFP driven TaoRNAi midgut.

(F) Quantification of p-H3+ cells in midguts of control (Su(H)ts>GFP), TaoRNAi lines, and combinations of TaoRNAi with the other RNAi or cDNA lines as indicated. The average number of p-H3+ cell staining per midgut is plotted. For all statistics in this report, the error bar is SEM and p value is from Student’s t test: **p < 0.01; NS, no significance with p > 0.05.

(G) qPCR for mRNA expression of upd3 in flies that contained the Su(H)ts>GFP and the indicated transgenes. After the temperature shift for 5 days, approximately 10 midguts from each sample were used for mRNA isolation and RT-PCR. The cycle number of each PCR was normalized with that of the rp49 in parallel PCR. The normalized expression of upd3 mRNA was divided by that of the control (GFP) and plotted as fold change. Student’s test: **p < 0.01.

(H–K) Confocal images of surface views of β-galactosidase (β-gal) antibody staining. Su(H)ts>GFP was used as the driver to express Tao dsRNA, msn dsRNA, and hpo dsRNA as indicated, in flies that also contained the upd3 promoter-lacZ reporter gene. Three different channels or color combinations of the same images are shown. (H) Su(H)ts>GFP, upd3-lacZ control midgut. (I) Su(H)ts>GFP, upd3-lacZ, Tao dsRNA midgut. (J) Su(H)ts>GFP, upd3-lacZ, msn dsRNA midgut. (K) Su(H)ts>GFP, upd3-lacZ, hpo dsRNA midgut. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(L) The indicated tagged constructs of Msn and Tao under the UAS promoter were co-transfected into S2 cells together with actin promoter-Gal4. After 2 days, the cells were harvested and the extract lysates were used for immunoprecipitation (IP) and western blots (WB) by using the indicated antibodies.

The error bars are standard error of the mean.

An important question is whether distinct upstream mechanisms are employed to control the activity and specificity of these different subfamilies of Ste20 kinases in various biological processes. In this report, we present results to show that ingested yeast particles in the midgut cause stretching of the epithelium, and probably elicit a mechanical signal that causes a reduction of Msn subcellular accumulation near the cytoplasmic membrane, reduction of Msn phosphorylation at the threonine 194 (T194) residue by the upstream kinase Tao (Thousand and one of the Ste20 family), and reduction of activity toward Wts to allow Yki-dependent intestinal growth.

RESULTS

Tao Functions in the Msn Pathway to Regulate Adult Midgut Homeostasis

We searched for upstream components that might regulate the Msn pathway by performing RNAi assays and looking for a similar over-proliferation phenotype in the midgut (Figure 1A). The esg-Gal4 is expressed robustly in both ISCs and EBs, while the Su(H)-Gal4 is expressed more specifically, albeit weaker, in many EBs (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Zeng et al., 2010). Together with tubulin-Gal80ts and UAS-mCD8GFP, the system [esgts>GFP and Su(H)ts>GFP] provides the temperature-sensitive control of the Gal4 activity and the monitoring of target cells that also express GFP (Amcheslavsky et al., 2011; Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006). Multiple independent transgenic UAS-double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) lines targeting non-overlapping sequences of Tao caused an increased number of GFP+ precursor cells and of phospho-histone 3-positive (p-H3+) mitotic cells (Figures 1B–1E).

Previous reports suggest that Tao is an upstream kinase of Hpo and MAP4Ks in various tissues, including midgut precursor cells (Boggiano et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2014; Meng et al., 2015; Poon et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2015). However, our results demonstrate that Msn acts mainly in EBs while Hpo acts in ECs (Figure 1A) (Li et al., 2014). Therefore, we speculated that Tao regulated Msn in EBs, perhaps in addition to regulating Hpo in ECs, to effect midgut homeostasis. We performed a series of experiments to assess the genetic interactions of Tao and Msn by using the Su(H)ts>GFP specifically expressed in EBs. Overexpression of Msn and Wts, but not Hpo, efficiently suppressed the mitotic count induced by Tao RNAi (Figure 1F). Diminishing Yki and Upd3 function by RNAi also suppressed the Tao RNAi-induced ISC proliferation (Figure 1F). We also observed that Tao RNAi could induce upd3 mRNA expression, which was efficiently suppressed by overexpression of Msn (Figure 1G). To visualize the midgut cell type involved, we utilized the upd3-promoter-lacZ reporter that has been shown to express in EBs and ECs after various stimulations. Both Tao RNAi and msn RNAi, but not hpo RNAi, caused expression of β-galactosidase (β-gal) protein in cells that largely co-localized with GFP that was also driven by the Su(H)Gal4 (Figures 1H–1K), suggesting that many of the cells involved are EBs. Together with the experiments (Figure S1) using the Myo1A Gal4 and esg Gal4 drivers, the results demonstrate that Tao functions similarly as Msn in EBs, while Tao also has a function as Hpo in ECs, consistent with our hypothesis (Figure 1A) (Li et al., 2014). Lastly, co-expression of tagged versions of Tao and Msn proteins in cultured S2 cells followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) of HA-tagged Msn from these cell extracts led to detectable FLAG-tagged Tao by western blot (Figure 1L). These genetic and biochemical experiments together support the idea that Tao has a function in EBs and acts upstream of Msn to regulate Yki activity and Upd3 expression for intestinal homeostasis.

Tao Acts as an Upstream Kinase to Phosphorylate Msn at the Threonine 194 Residue

Msn becomes highly active after okadaic acid (OA) treatment in S2 culture cells (Kaneko et al., 2011). OA is a phosphatase inhibitor and likely causes sustained phosphorylation of kinases such as those in the Ste20 family that required phosphorylation as an activation mechanism. Therefore, we performed a mass spectrometry assay under this condition and identified multiple phosphorylation sites that are potentially critical for the activation process (Figures 2A and S2A). Some of the phosphorylated residues are located in an extensively conserved region within the kinase domain. Moreover, the equivalents of one of these residues, T194, in other Ste20 kinases have been proposed to provide a conformational role in modulating the kinase activity (Boggiano et al., 2011; Delpire, 2009; Poon et al., 2011). We generated an antibody by using a peptide containing phospho-T194 (Wang et al., 2016), and showed that transfected Msn had highly increased p-T194 signal after OA treatment and the signal was abolished by phosphatase treatment of the extract (Figure 2B lane 1–3). Co-transfection of Tao caused an increase of signal detected by this antibody (Figure 2B lane 4–6). The T194A mutants in various assays showed no such signal (Figures 2E–2G). A series of experiments also demonstrated that the mammalian Misshapen-like kinase 1 (MINK1, also called MAP4K6) showed a significant signal by this same antibody (Figure 2C). Mutating the equivalent T187 of MINK1 eliminated the signal, while the ATP binding site mutant (K54R) that should abolish the kinase activity still had such phosphorylation (Figure 2C). Examination of endogenous MINK1 in HEK293 cells by using an anti-MINK1 antibody for IP followed by p-T187 blotting revealed a detectable signal and, more importantly, this signal was increased when the mammalian Taok1 was co-transfected (Figure 2D). These results together demonstrate that T194 in Drosophila Msn and the equivalent T187 in mammalian MINK1 exhibit a conserved phosphorylation event that is targeted by Tao.

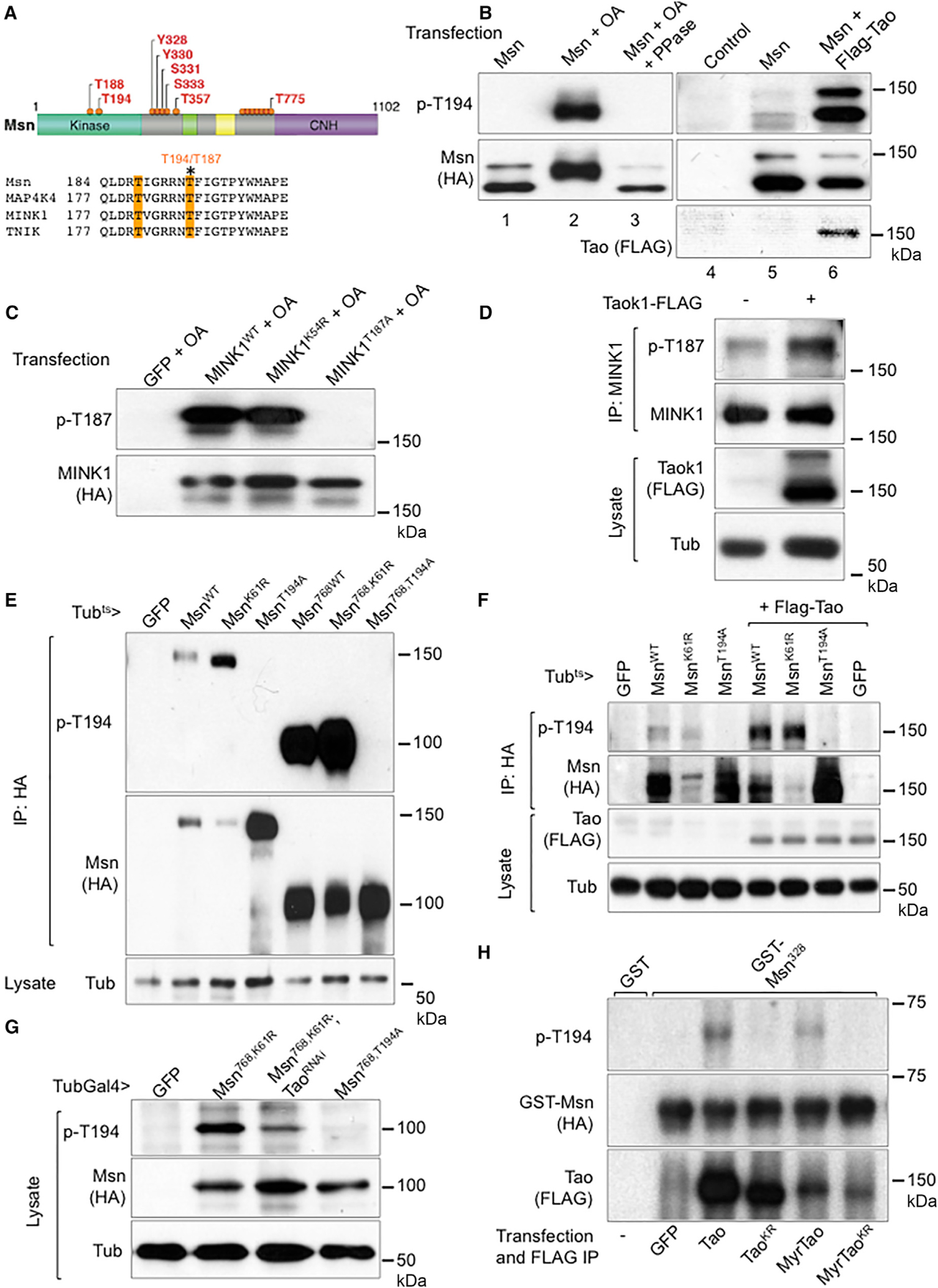

Figure 2. Tao Phosphorylates Msn at T194.

(A) An illustration of phosphorylation sites identified by mass spectrometry of Msn-HA protein from transfected S2 cells after OA treatment and IP by HA antibody. The yellow shade in the lower panel highlights two of the phosphorylation sites in the kinase domain and the asterisk indicates the T194/T187.

(B) Western blots using transfected S2 cell extracts and the indicated antibodies. The cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and after 48 hr were treated with 125 nM OA or control DMSO for 1 hr and then used for extract preparation. The phosphatase treatment (PPase) was carried out by adding the enzyme to the extracts and incubating for 30 min prior to SDS gel separation. The Tao co-transfection experiments used a lower dose of 5 nM OA (lanes 4–6).

(C) Western blots using extracts of transfected HEK293 cells. The indicated plasmids were transfected and after 48 hr the cells were treated with 125 nM OA for 1 hr and used for extract preparation.

(D) Western blots using extracts of HEK293 cells. Cells were transfected with the vector plasmid or Flag-TaoK1 plasmid. The extract or IP lysates were analyzed by western blots as shown. A mouse anti-TNIK/MINK1 (BD Transduction Laboratories) was used for IP and a rabbit anti-MINK1 (Bethyl) was used for blots.

(E) Western blots using gut extracts from transgenic flies harboring the indicated constructs. Flies were incubated at 29°C for 3 days before gut dissection, extraction, and immunoprecipitation. The 768 truncation constructs contained amino acids 1–768 of the Msn protein, with the CNH domain deleted.

(F) Western blots using gut extracts from transgenic flies harboring the indicated constructs. Flies were incubated at 29°C for 3 days before gut dissection, extraction, and immunoprecipitation. The Msn constructs were full length proteins with the indicated mutations.

(G) Western blots using gut extracts from transgenic flies as indicated. Because the Msn768 constructs expressed at a higher level, the extracts without IP were used for these western blots.

(H) Western blots using mixtures from in vitro kinase assays. GST fusion proteins were purified from bacteria expressing the constructs. The GST-Msn328 contained amino acids 1–328 spanning the kinase domain. The Tao proteins were IP from transfected S2 cells, which were treated with 50 nM OA before harvesting, mixed with purified GST-Msn proteins in the presence of ATP for 30 min at 30°C, and the mixtures were analyzed by western blot.

To examine the Msn T194 phosphorylation in the midgut, we generated multiple transgenic fly lines harboring different UAS-Msn constructs and expressed under the control of the ubiquitous driver tubulin-Gal4/Gal80ts (Tubts>). Midgut extracts were used for IP and western blotting. The wild-type Msn and ATP binding site mutant MsnK61R showed a similar T194 phosphorylation signal, while the MsnT194A mutant did not (Figure 2E). The Msn amino acid (aa) 1–768 truncated versions had the C-terminal CNH domain deleted and showed the same pattern but with much higher signal (Figure 2E). Co-expressing a transgenic Tao increased the p-T194 signal (Figure 2F), while Tao RNAi decreased the signal (Figure 2G). An in vitro kinase assay was carried out by using bacterially expressed and purified glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein that contained the N-terminal 300 aa of Msn. Immunoprecipitated Tao from transfected and OA treated S2 cells were used and T-194 phosphorylation signal was detected; such phosphorylation was not observed when a kinase dead TaoKR point mutant was used (Figure 2H). Meanwhile, a knockin allele that produces an endogenous GFP-Msn also exhibited detectable T194 phosphorylation (see Figures 6A and 6B). Together, the results demonstrate that the T194 residue of Msn has detectable phosphorylation in vivo and that Tao is both necessary and sufficient for promoting this phosphorylation event.

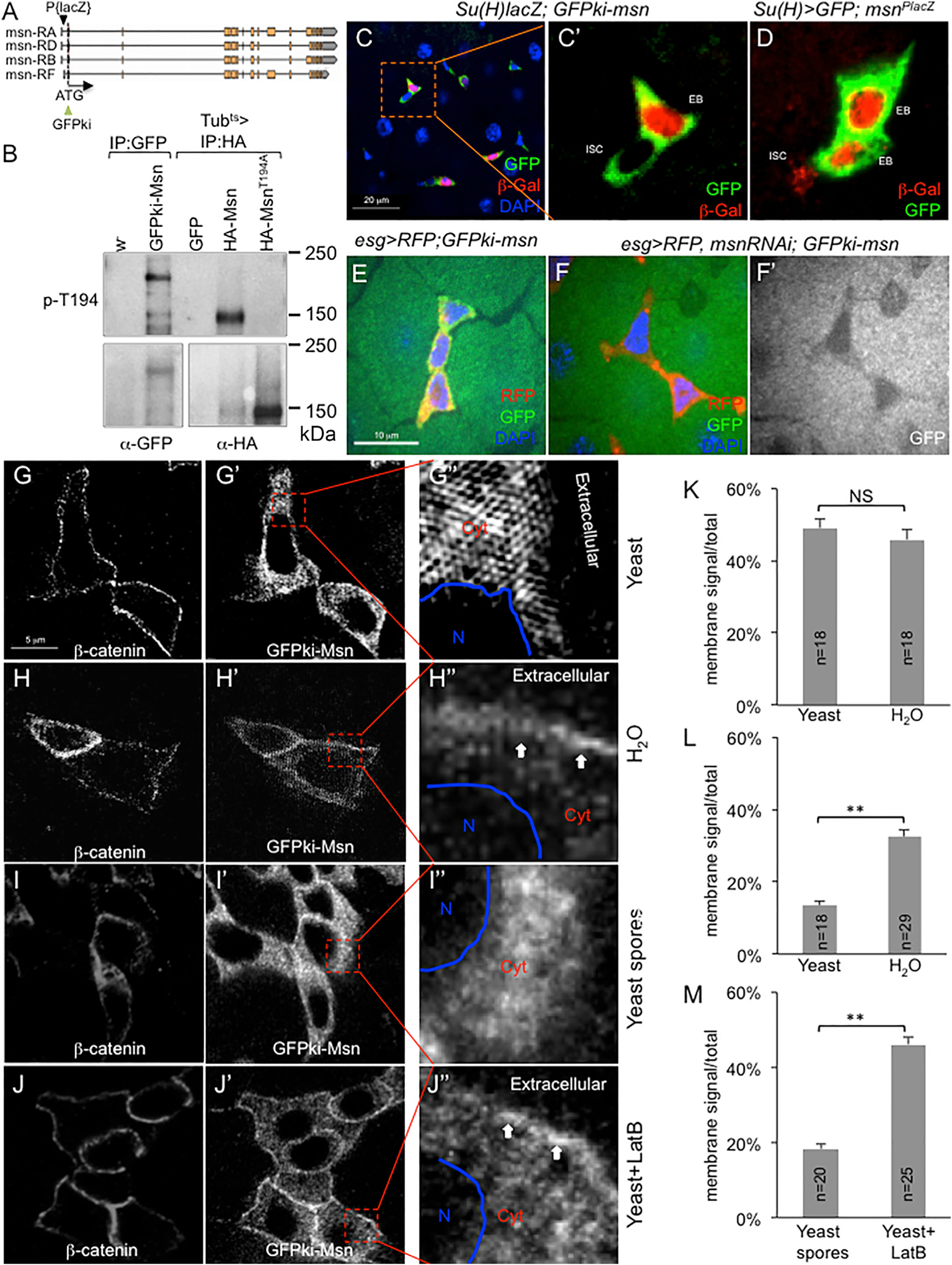

Figure 6. Dynamic Association of Endogenous Msn with the Cytoplasm Membrane.

(A) The msn genomic locus, showing the GFP knockin replacing the initiation codon, and the P element lacZ (msnP06946) insertion into the msn 5′UTR.

(B) Western blot analysis of gut extracts. Anti-GFP antibody was used for IP for w− and GFPki-msn gut extracts, and anti-HA antibody was used for IP for Tubts>UAS transgenic fly gut extracts. Anti-p-T194 blot is shown in the upper panel, and anti-GFP or anti-HA blot is shown in the lower panel.

(C–F) Confocal images of posterior midgut precursor cell nests. The GFP (green) in (C) represents endogenous Msn protein expression in both ISCs and EBs, while the Su(H)Gal4-driven β-gal (red) shows specific expression in EBs. The red β-gal staining in (D) represents msn promoter-driven products, while Su(H)Gal4-driven GFP (green) shows specific expression in EBs. In (E) and (F), the esg>UAS-RFP is shown in red and the GFPki-Msn is shown in green (or white in F′). It is noteworthy that, as seen in (E)–(F′), there is a low level of GFP signal in ECs, which is, however, substantially lower than that in EBs (see C). This low level of expression in ECs may be meaningful and consistent with the lower but significant msn-RNAi-induced proliferation phenotype when using the Myo1A EC driver (Li et al., 2014).

(G–J) High-resolution images of β-catenin and GFPki-Msn in midgut cell nests. The GFPki-Msn flies were fed with the indicated ingredients for 12 hr. Guts were dissected and stained for β-catenin. Imaging of β-catenin and GFP was performed under a super-resolution (G–H′′) or a confocal microscope (I–J′′), with similar results. The images shown have been converted to black and white for each color. In the enlarged views, N indicates the nuclear area, Cyt indicates cytoplasm, and Extracellular space is as indicated. The arrows in (H′′) and (J′′) point to the higher GFP signal near the cytoplasmic membrane domain.

(K–M) Quantification of β-catenin and GFPki-Msn signal distribution by using confocal images of individual cells similar to those shown in (G)–(J). The distribution of β-catenin helped to define the membrane-associated region (Figures S4A and S4B). The signal distribution along the membrane-cytoplasm-nuclear axis of each cell is normalized and calculated as the ratio of membrane/total. The number of individual cells analyzed in each feeding condition is indicated as “n” in each bar graph. The average of signal distribution is plotted as percentage of total signal as shown. (K) Comparison of the membrane β-catenin signal in the two feeding conditions. (L) Comparison of the membrane GFPki-Msn signal in the two feeding conditions. (M) Comparison of the membrane GFP-kiMsn signal in the two feeding conditions. Student’s t test: **p < 0.01. NS, not significant.

The error bars are standard error of the mean.

Threonine 194 Is an Essential Residue for the Activity of Msn toward Wts

We surmise that, as a target of Tao and essential for the Msn kinase activity, the T194 residue of Msn is an important functional link for the upstream regulators to control downstream events and ultimately tissue growth. To test this hypothesis, we first per formed transgenic expression of MsnK61R or MsnT194A in the adult midgut to examine their growth-promoting activity. The expression of these two mutants by the precursor cell drivers was sufficient to cause an increased number of mitotic ISCs (Figure 3A), an increased upd3 expression (Figure 3B), and an increased number of precursor cells marked by esg>GFP (Figures 3C–3F). For comparison, expression of wild-type Msn could have an opposite phenotype of growth suppression (see also Figures 1F, 1G, 4C, 4D, and 7I). All these results suggest that MsnT194A functions as a dominant negative, equivalent to the ATP binding site mutant MsnK61R.

Figure 3. T194 Is an Essential Residue for Msn Activities.

(A) The plot shows the average of p-H3+ staining counts in whole midguts. The Gal4ts drivers were crossed with the indicated UAS transgenic constructs, and the resulting flies were incubated at 29°C for 5 days, followed by gut dissection and p-H3 antibody staining. Student’s t test: **p < 0.01.

(B) Su(H)Gal4ts and UAS transgenic flies were established and used for temperature shift, whole gut dissection, RNA isolation, and qPCR for the expression of upd3. The level of expression in the GFP control fly guts was set as 1 and the expression in the other strains was plotted as fold increase. Student’s t test: **p < 0.01.

(C–F) esgGal4ts>GFP and UAS transgenic flies were established and used for temperature shift, gut dissection, and confocal imaging as shown. (C) esgts>GFP driven control midgut. (D) esgts>GFP driven wild-type Msn full-length protein overexpression in midgut. (E) esgts>GFP driven Msn full-length protein with the K61R mutation overexpression in midgut. (F) esgts>GFP driven Msn full-length protein with the T194A mutation overexpression in midgut. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(G) Western blots using transfected S2 cell extracts and the indicated antibodies. The cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and after 48 hr were treated with 125 nM OA or control DMSO for 1 hr and then used for extract preparation. The red arrow in lane 7 indicates a slower mobility Wts protein in the presence of co-transfected wild-type Msn.

(H) Western blots using transfected S2 cell extracts and the antibodies as indicated. A lower dose of 50 nM OA was used in these experiments. WtsTA contained the T1077A point mutation.

(I) Western blots using transfected S2 cell extracts and the antibodies as indicated. A lower dose of 50 nM OA was used in these experiments. WtsTA contained the T1077A point mutation. All other Wts, Msn, Hpo, and Tao were full-length constructs.

(J) Western blots using mixtures from in vitro kinase assays. GST fusion proteins were purified from bacteria expressing the constructs. The GST-WtsC contained amino acids 707–1105 spanning the C-terminal half of Wts. WtsCTA contained the T1077A point mutation in the C-terminal fragment. MsnKR contained the K61R point mutation, a kinase dead version. The Msn proteins were IP from transfected S2 cells, which were treated with 50 nM OA before harvesting, and then mixed with purified GST-Wts proteins in the presence of ATP for 30 min at 30°C. The mixtures were analyzed by gel separation and western blot.

The error bars are standard error of the mean.

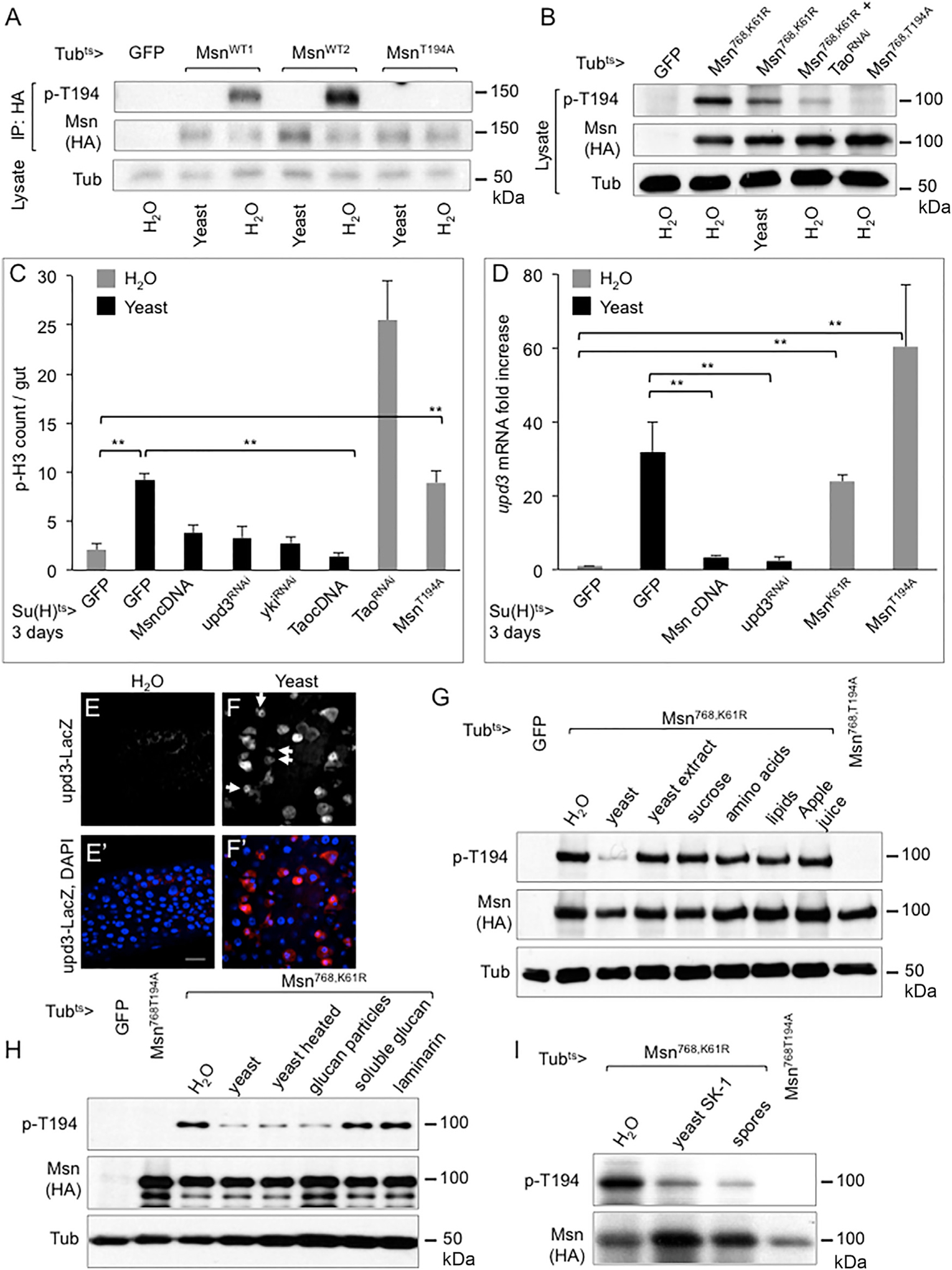

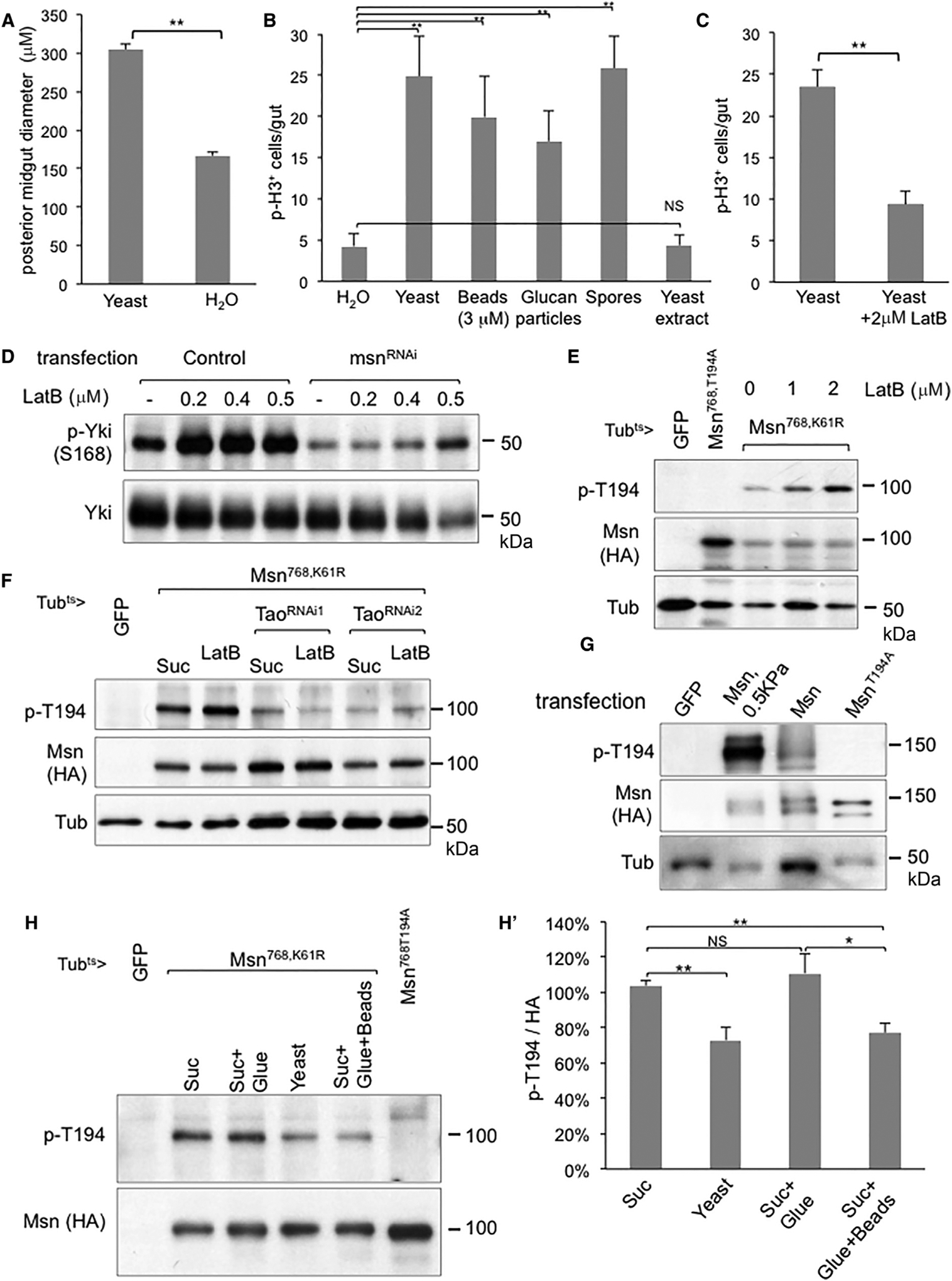

Figure 4. Regulation of Msn T194 Phosphorylation by Ingested Yeast Particles.

(A) Western blots using gut extracts of transgenic fly lines harboring the UAS constructs as indicated. The flies were shifted to 29°C on normal food for 3 days, starved for 2 hr, and fed with either H2O or 20% yeast paste for 12 hr at 29°C. The guts were dissected and used for protein extraction, IP, and western blots. Two independent transgenic MsnWT (wild-type) lines were used.

(B) Western blots using whole gut lysates from transgenic flies carrying the indicated UAS constructs. Temperature shift and analysis were as described above.

(C) Su(H)Gal4ts and UAS transgenic flies were established and used for temperature shift and yeast or H2O feeding, together for 3 days. Guts were used for staining and p-H3 counts. Student’s t test: **p < 0.01.

(D) Su(H)Gal4ts and UAS transgenic flies were established and used for temperature shift, gut dissection, RNA isolation, and qPCR. Yeast or H2O feeding were carried out for the last 1 day of the 3-day temperature shift at 29°C. The expression of upd3 was plotted as fold change comparing with the control. Student’s t test: **p < 0.01.

(E and F) Confocal images of β-gal staining of midgut from flies carrying the upd3-LacZ reporter. The arrows in (F) indicate some of the precursor cells, which had smaller sizes, with upd3-lacZ expression. (E) The flies were fed with H2O for 3 days at 25°C. (F) The parallel experiment with the flies fed with 20% yeast paste. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(G) Western blot analysis using gut extracts from flies harboring the UAS transgenes as indicated. The flies were fed for the last 12 hr of the 30day temperature shift at 29°C with H2O, 20% live yeast paste, 5% yeast extract, 5% sucrose, 3.2 g/L essential amino acids, 0.1 g/L lipids, or 5% apple juice (from concentrated) as indicated. Guts were dissected from 10 flies of each sample and used for extract preparation.

(H) Western blot analysis of the gut extracts is shown. The feeding experiments were performed as above using the yeast preparations as indicated. Glucan particles were highly extracted yeast that contains essentially only the glucan shells (see STAR Methods). The soluble glucan and laminarin were commercial preparations.

(I) The SK-1 was the super-sporulation strain used. The normal SK-1 yeast or spore preparations were mixed with H2O to make 20% pastes and used for feeding. Guts were dissected and used for western blot analysis as shown.

The error bars are standard error of the mean.

Figure 7. Membrane Tethering of Msn Enhances Tao-Dependent Phosphorylation, but Membrane Association of Msn is Tao Independent.

(A–D) Confocal images of posterior midgut EBs from flies expressing the indicated HA-tagged Msn proteins. The anti-HA staining is shown as white. (A) esgts>GFP driven wild-type HA-tagged Msn full-length protein overexpression in a midgut precursor cell. (B) esgts>GFP driven HA-tagged Msn T194A mutant full-length protein overexpression in a midgut precursor cell. (C) esgts>GFP driven myristoylation sequence- and HA-tagged Msn full-length protein overexpression in a midgut precursor cell. (D) esgts>GFP driven myristoylation sequence- and HA-tagged Msn T194A mutant full-length protein overexpression in a midgut precursor cell.

(E) Distribution of immunofluorescent signal of HA-Msn and myr-HA-Msn in midgut EBs. Quantification and normalization are as described in Figure 6 and shown in Figures S4G and S4H. The average membrane/total ratio is plotted as shown. Student’s t test: **p < 0.01.

(F) Western blot using extracts from S2 cells transfected with the indicated cDNA and dsRNA constructs. The cells were harvested 48 hr after transfection and used for extract preparation and analysis.

(G) Western blot using extracts from HEK293 cells transfected with the MAP4K4 constructs.

(H) Western blot using gut lysates or IP extracts from transgenic flies expressing the indicated proteins. Approximately 250 guts were dissected from each strain and put into the lysis buffer that also contained 500 nM OA. The lysate was used for IP using the anti-HA antibody and subsequently for western blot as shown.

(I) qPCR of upd3 mRNA expression in midguts of young and aged flies. Transgenic flies were aged for 7 or 30 days at room temperature and then shifted to 29°C for 5 days to allow transgene expression. The guts were dissected for total RNA isolation and qPCR. Student’s test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

(J–M) Confocal images of posterior midgut precursor cell nests. The fly strain used was GFPki-Msn crossed with flies carrying esgts> (no UAS-GFP) or esgts>TaoRNAi. The resulting flies were incubated at 29°C for a total of 24 hr for transgenic expression, with H2O or 20% yeast paste feeding in the last 12 hr. The flies were used for gut dissection and immunofluorescent staining. The images are shown in different colors as indicated and the boxed areas in the middle panels are enlarged as shown in the right panels. (J) GFPki-Msn, esgts> flies with yeast feeding. (K) GFPki-Msn, esgts> flies with water feeding. (L) GFPki-Msn, esgts>TaoRNAi flies with yeast feeding. (M) GFPki-Msn, esgts>TaoRNAi flies with water feeding.

(N) A model illustrating the dynamic association of Msn with the cytoplasmic membrane. Accumulation of food particles causes stretching of the single cell-layered midgut epithelium. Mechanosensing mechanisms may cause release of Msn from the membrane, lower T194 phosphorylation, and lower activity of Msn toward Wts, thereby allowing more Yki activity to promote midgut growth.to promote midgut growtThe error bars are standard error of the mean.

In co-transfection experiments, Msn could change the phosphorylation of full length Wts protein and shift its mobility on SDS-PAGE (Li et al., 2014). OA treatment likely inhibited phosphatases and already resulted in a substantial shift to a slower mobility of the Wts protein (black arrow, Figure 3G, compare with DMSO). The addition of wild-type Msn, which by itself may require OA for its activation in these experiments, caused a shift to a further slower mobility (Figure 3G, red arrow), while the addition of MsnK61R or MsnT194A mutant did not cause a similar change of the Wts mobility. To examine a specific target site, we used an antibody that recognizes phosphorylated threonine 1077 residue of Wts, which has been shown to be a target of Hpo (Yin et al., 2013). The Wts p-T1077 signal on the blot was modestly increased after OA treatment, while the co-transfection of Msn increased this signal substantially. The MsnK61R and MsnT194A mutants lost such a function (Figure 3H). Further co-transfection experiments demonstrated that Tao could collaborate with either Msn or Hpo to increase the Wts T-1077 phosphorylation (Figure 3I). Lastly, immunoprecipitated Msn could increase the phosphorylation of T-1077 by using a bacterially expressed and purified Wts C-terminal protein fragment (Figure 3J). In all these experiment, the T1077A mutation abolished or reduced the phosphorylation signal.

A phosphomimetic mutation of Msn, the T194E, exhibited an increased activity toward Wts at the T1077 site at the C terminus (Figure S2B). Meanwhile, we also used the Wts1 fragment (N-terminal aa 1–318), which was shown to be a substrate for Hpo (Degoutin et al., 2013), and analyzed the overall phosphorylation by phos-tag gels. The acrylamide-pendant Phos-tag ligand (Phostag AAL-107) provides a phosphate affinity SDS-PAGE such that higher phosphorylated proteins appear to have slower mobility (Kinoshita et al., 2012). The result showed that the T194E phosphomimetic mutant was the most active, while the T194A mutant was the least, in increasing the phosphorylation of Wts1 in transfected cells (Figure S2C, red arrows). Therefore, the results together support the idea that T194 phosphorylation changes the kinase activity of Msn toward Wts, probably at multiple target residues.

Physiological Regulation of the Msn T194 Phosphorylation by Ingested Yeast Particles

Having established the genetic and biochemical pathway of Tao-Msn-Wts, we used the T194 phosphorylation of Msn as an in vivo assay to search for upstream physiological processes that could change the pathway activity, and thus intestinal homeostasis. We tried feeding various chemical and biological agents, such as dextran sulfate sodium, bleomycin, and bacteria (Amcheslavsky et al., 2009; Chatterjee and Ip, 2009), but in the process observed a significantly higher T194 phosphorylation after the feeding of water for 12 hr when comparing with that after the feeding of yeast (Figure 4A). Water feeding is sufficient to keep flies alive for several days but results in a low growth condition, while yeast is a natural food for flies and stimulates high growth. Therefore, as a repressor of growth, Msn had high T194 phosphorylation representing high activity correlated well with the repression of growth after water feeding, and vice versa for yeast feeding. We further used the truncated version Msn768,K61R that had more readily detectable phosphorylation from gut lysates without the need of IP to show that the T194 phosphorylation was higher after water feeding and that this phosphorylation was substantially reduced when Tao RNAi was included (Figure 4B).

Further assays suggest that Msn, Yki, and Upd3 all have functional relevance in yeast feeding-induced growth. The ISC mitotic index represented by the number of p-H3+ cells was higher in yeast-fed flies but efficiently suppressed by overexpression of Msn or Tao (Figure 4C). The high growth was also suppressed by the loss of Yki or Upd3 (Figure 4C). Yeast feeding caused a 30-fold higher level of upd3 mRNA expression in the midgut when compared with that of water feeding (Figure 4D). This high upd3 expression after yeast feeding was suppressed by overexpression of Msn, similar to that after upd3 RNAi. Meanwhile, the low upd3 mRNA level associated with water feeding could be increased by expressing the MsnK61R or MsnT194A dominant negative mutant. Lastly, yeast feeding can induce EBs to express upd3, as visualized by the upd3-lacZ reporter in the midgut (Figures 4E and 4F, arrows). These results are consistent with the idea that midgut growth in response to feeding can be mediated by changing Msn activity, such as through T194 phosphorylation.

While live yeast is a rich food source for wild-type flies, a series of experiments suggest that it is not nutrient sensing that reduces Msn activity. Adding to plain water with yeast extracts, sugar, aa, lipids, or apple juice did not show the same effect as live yeast in lowering the T194 phosphorylation (Figure 4G). Yeast is also a pathogen for immune-compromised mutant flies (Ha et al., 2009). However, heat-killed yeast still had the same effect as live yeast, while neither soluble glucan nor laminarin could lower the T194 phosphorylation (Figure 4H), suggesting that it is not the pathogenic effect or pattern recognition that regulates the Msn pathway. Meanwhile, empty glucan particles, obtained after extensive extraction of whole yeast (Young et al., 2007), when fed to flies were equally efficient to reduce Msn phosphorylation (Figure 4H). Furthermore, by using a super-sporulation strain SK-1 (Figures S3A and S3B), we showed that yeast spores that had different outer cell walls, and therefore were not digestible by fly gut enzymes (Coluccio et al., 2008), nonetheless had a similar effect in reducing T194 phosphorylation (Figure 4I). Therefore, ingestion of insoluble yeast particles that have no nutritional value is sufficient to provide a physiological signal that regulates Msn phosphorylation.

Msn Phosphorylation as a Mechanosensing Mechanism

The results as shown above suggest a possibility, based on the mechanosensing response of Wts-Yki in previously proposed models (Dupont, 2016; Dupont et al., 2011; Halder et al., 2012; Sansores-Garcia et al., 2011), that accumulated yeast particles in the midgut provide a stretching effect to regulate growth via the Msn-Wts-Yki pathway. We performed a series of experiments and the results support this hypothesis. First, flies normally ingest substantial amounts of yeast and that resulted in a significant gut distention (Figure 5A, Figure S3C). Second, the stem cell division in the midgut was highly increased after feeding of live yeast, empty glucan particles, or yeast spores, but not yeast extract (Figure 5B), which correlates very well with the change of T194 phosphorylation under these conditions. Third, Latrunculin B (LatB) treatment causes a disruption of actin polymerization, reduction of cell stretching, and an increase of Yki phosphorylation, and thus represents a cell-based mechanosensing assay (Meng et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2015). This LatB induced endogenous Yki phosphorylation in KC cells was substantially reduced after msn RNAi (Figure 5D). Meanwhile, feeding of LatB to flies was sufficient to block the growth induced by yeast feeding (Figure 5C). LatB feeding also increased Msn phosphorylation (Figure 5E), which was reduced when TaoRNAi was included (Figure 5F). As a control, feeding of LatB did not suppress the growth induced by the DNA damaging agent bleomycin (Figure S3D). Fourth, changing the stiffness of cell culture substrate represents a change of mechanosensing. By using the adherent S2R cells we showed that the Msn T194 phosphorylation was higher in a lower stiffness substrate (Figure 5G), demonstrating that Msn is more active in a condition of less stretching due to reduced cell spreading.

Figure 5. Msn Phosphorylation as a Mechanosensing Mechanism.

(A) Wild-type flies were fed with yeast paste or plain water for 12 hr and then dissected and fixed for microscopy (see Figure S3C). The images were then used for measurement of posterior midgut diameter, using more than 20 guts for each condition, and the average is plotted as shown. Student’s t test: **p < 0.01.

(B) Mitotic p-H3+ cell count of whole midguts from wild-type flies, after feeding with water, live yeast, polystyrene beads, empty glucan particles, yeast spores, or soluble yeast extract. Student’s t test: **p < 0.01.

(C) Similar feeding experiments of wild-type flies either in live yeast or yeast + latrunculin B (LatB) were performed and the midgut p-H3+ cell count average was plotted as shown. Student’s t test: **p < 0.01.

(D) Analysis of endogenous Yki phosphorylation by using the phosphor-S168 antibody. KC cells were used after mock transfection (control) or with msn dsRNA as indicated, and treated with LatB for 1 hr prior to harvesting for extract preparation.

(E) Transgenic flies expressing the indicated constructs were used for feeding of LatB and the guts were dissected for western blot analysis.

(F) Similar transgenic fly and LatB feeding experiments were performed with two different transgenic lines expressing dsRNA of Tao.

(G) S2R cells were transfected with the indicated UAS-msn constructs together with an Actin-Gal4 driver plasmid. After transfection for 24 hr, some cells were re-plated onto soft stiffness (0.5 kPa) hydrogels bounded on regular dishes. After 12 hr, the cells were harvested and used for western blot analysis.

(H and H′) Western blot analysis using gut extracts from the transgenic flies after temperature shifted to express the transgenes and then put into an empty vial for 2 hr prior to feeding experiments. For gluing, the posterior tip of fly abdomen was dipped into a drop of water-based nail polish to block the excretion. The normal and glued flies were fed with the indicated particles in 5% sucrose solution for 8 hr at 29°C and the guts were dissected for extract preparation. The signal of p-T194 and HA on the blots were quantified by the ImageJ software, and the ratio was calculated and normalized to that of sucrose-fed flies. The average of three independent experiments was plotted as shown in (H′). Student’s test: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

The error bars are standard error of the mean.

Lastly, we performed a feeding experiment using plastic beads that should bear no similarity to yeast particles except being indigestible particles. We observed that the 3 μm beads were better ingested than other beads with bigger sizes. Feeding of these plastic beads was similar to feeding of water such that they did not help the survival of the flies beyond 3 days (Figure S3G) but nonetheless could stimulate the p-H3 count in the midgut (Figure 5B). These 3 μm beads after ingestion, however, were not retained in the gastrointestinal tract as well as the yeast particles. Therefore, we glue the rear end of the flies to help the retention of the beads during an experimental period of 8 hr to examine Msn phosphorylation. Under this condition, we observed that feeding of plastic beads had a similar effect as feeding of yeast in reducing T194 phosphorylation with statistical significance (Figures 5H and SH′). These results together support the model that ingestion of indigestible particles causes midgut distention and the subsequent mechanosensing leads to reduced Msn phosphorylation, thereby increasing Yki activity to promote adaptive growth.

An Endogenous GFPki-Msn Protein Exhibits Dynamic Localization Near the Cytoplasmic Membrane

To investigate how Msn activity might be regulated by stretching of the midgut epithelium, we used CRISPR genome engineering to generate a knockin allele to produce an endogenous Msn with a GFP fusion to the N terminus, designated as GFPki-Msn (Figure 6A). While msn loss-of-function mutant alleles are embryonic lethal and exhibit dorsal closure defect, as well as other defects such as misshaped eyes (Su et al., 1998; Treisman et al., 1997), multiple GFPki-Msn homozygous fly lines were viable and showed no morphological abnormality, suggesting that this GFP fusion does not inhibit the protein function. Moreover, T194 phosphorylation could be detected with the immunoprecipitated GFP fusion protein from midgut extracts (Figure 6B). In the adult midgut of these knockin lines, the GFP fluorescent signal was easily detectable in precursor cells but not in mature ECs or EEs (Figure 6C), remarkably consistent with the functional requirement of Msn in EBs. A previously used lacZ insertional allele of msn also showed β-gal staining to be similarly high in EBs (Figure 6D). msn RNAi in the midgut by using the esg-Gal4 driver in precursor cells was sufficient to knock down the GFP signal (Figures 6E, 6F, S4I, and S4J). Therefore, this GFPki-Msn likely represents an endogenous Msn expression pattern with normal Msn protein function.

We then examined the distribution of this GFPki-Msn in midgut precursor cells under various feeding conditions. After feeding live yeast or yeast spores, the GFP signal appeared to be cytoplasmic (Figures 6G’, 6G′′, 6I′, and 6I′′). After plain water or yeast + LatB feeding, however, the GFP signal appeared to be higher near the cytoplasmic membrane (Figures 6H’, 6H′′, 6J′, and 6J′′).

To quantify these GFP signal distributions, we first used double staining to examine the well-known membrane-associated protein Armadillo/β-catenin in the same cells under the same conditions (Figures 6G, 6H, 6I, and 6J). We assigned starting signal around the edge of cytoplasmic membrane as distance 0.00 and ending signal around the edge of nuclear membrane as distance 1.00. The signal intensity along this cytoplasmic membrane-nuclear membrane axis in each cell was normalized (see Figure S4 and legend) and the signal distribution was plotted along this axis. The β-catenin signals peaked at approximate distance 0.33 (Figures S4A and S4B). Therefore, we designated the distance from 0.00 to 0.33 as the cytoplasmic membrane-associated region. Importantly, the normalized signal distribution of β-catenin under high yeast or plain water feeding showed no difference (Figure 6K). In contrast, a significant shift toward the cytoplasmic membrane-associated region was observed for the GFPki-Msn signal after plain water or yeast + LatB feeding when compared with that after live yeast or yeast spore feeding (Figures 6L, 6M, and S4C–S4F). These results demonstrate that, under the low growth feeding conditions, Msn has a higher membrane association, and that yeast feeding reduces Msn accumulation near the membrane.

Membrane Tethering of Msn Enhances Tao-Dependent Phosphorylation, but Membrane Association Is Tao Independent

We hypothesize that localization near the cytoplasmic membrane allows Msn to interact better with the upstream components and results in T194 phosphorylation to inhibit growth. To gain support for this hypothesis, we performed a series of experiments using various Msn and mammalian MAP4K4 constructs expressing in culture cells and midgut cells. Adding a myristoylation signal peptide sequence at the N termini leads to highly increased kinase activities of Msn and MAP4K4 in culture cell assays (Kaneko et al., 2011). When expressed in transgenic midguts, this myristoylation sequence led to an increased membrane association of wild-type and T194A Msn in precursor cells (Figures 7A–7D). Quantification of the staining in multiple cells demonstrated that the average membrane association was increased from 22% to 42% of total fluorescence signal (Figures 7E, S4G, and S4H). In both Drosophila and mammalian cell transfection experiments, the myr-Msn and myr-MAP4K4 constructs showed higher T194/T187 phosphorylation signals, which was also dependent on Tao (Figures 7F and 7G). Transgenic expression of myr-Msn also had higher T194 phosphorylation in midgut extracts (Figure 7H). It is noteworthy that we consistently observed lower steady state protein level of all the myristoylated constructs when compared with that of the wild-type construct and nonetheless the signal of T194 phosphorylation was consistently higher.

The proliferation measured by p-H3+ count in the midgut is low under normal growth condition (e.g., Figures 3A and 3B, GFP controls) and therefore it is difficult to repress the mitotic count significantly when expressing gain-of-function mutants. Nonetheless, we established an in vivo gain-of-function assay of myr-Msn, such that in aged fly guts (30 days after eclosion) when higher expression of upd3 RNA was observed, the myr-Msn could repress this expression more efficiently than wild-type Msn (Figure 7I). These results together demonstrate that the myristoylation signal peptide increases membrane association, which correlates with an increased T194 phosphorylation and activity of Msn.

To dissect whether the Tao phosphorylation of Msn is a prerequisite for membrane association, we combined the Tao RNAi construct with the GFPki-Msn allele and performed feeding experiments. In the presence of Tao RNAi, we still observed Msn membrane association in the water-fed flies (Figures 7J–7M).

Lastly, we generated a knockin allele, Tao-kiRFP, and obtained a similar allele, Tao-kiVenus (Poon et al., 2016), and both showed low but detectable expression in precursor cells after antibody staining (Figures S5A and S5B). In comparison, a Hpo-kiVenus allele (Poon et al., 2016) did not show such expression (Figure S5C). We also did not observe a change of Tao protein distribution after water feeding (Figures S5G and S5H). Therefore, all the results suggest that the increased Msn T194 phosphorylation is dependent on Tao, while the dynamic Msn membrane association is not dependent on Tao.

DISCUSSION

Depletion of Msn by genetic approaches in midgut EBs leads to activation of Yki, increased production of Upd3, and a strong hyperplasia phenotype (Li et al., 2014). Such results indicate that, under normal growth conditions, at least a portion of Msn is already active and sufficient to restrict ISC-dependent growth. However, it was not clear whether any physiological signal could change Msn activity to modulate midgut homeostasis. The results shown in this report suggest that under low growth conditions Msn has a higher localization near the cytoplasmic membrane, and once near the membrane Msn is phosphorylated at T194 by Tao more efficiently or phosphorylation is retained more efficiently. These activated Msn in turn can better phosphorylate Wts, which inhibits Yki and Upd3 expression. Under high growth conditions, such as ingestion of yeast particles, the stretching of the epithelium causes reduced membrane association of Msn, thereby reducing the T194 phosphorylation and the kinase activity of Msn to allow more Yki to promote tissue growth. Msn fits the role of being a rheostat that can be dialed up or down via membrane association and T194 phosphorylation, by the physiological process of food intake and subsequent epithelium stretching, to regulate the appropriate amount of growth factor production (Figure 7N).

The mechanism that controls the dynamic association of Msn with the cytoplasmic membrane is not known. We speculate that Msn can come near the membrane from cytoplasm by transporters or via passive diffusion. Once near the membrane, Msn may interact with a membrane protein or complex that is the sensor of mechanical signal induced by food intake. While we show in this report that Tao functions upstream of and forms a complex with Msn, the knockin Tao fusion proteins appear to be broadly cytoplasmic in EBs, similar to that of mammalian TaoK1 in transfected cells (Yustein et al., 2003). More importantly, no increased membrane association of Tao was observed after water feeding, and Tao RNAi did not affect Msn membrane association. Therefore, we propose that other proteins may serve as the membrane anchor for Msn. One such possibility is the GTPase Rap2A, which has been shown in transfected mammalian cells to bind to the Msn homologs (Taira et al., 2004).

The Yki pathway has been implicated in transmitting mechanical signals to regulate cell growth (Dupont, 2016; Halder et al., 2012). Our results suggest that accumulation of yeast particles in the midgut causes a stretching of epithelium that correlates with reduced Msn membrane localization, phosphorylation, and activity. In culture cell experiments, the manipulation of substrate stiffness or stretching of cell sheets changes the mechanical contact that leads to altered Wts/Lats and Yki/YAP activities (Dupont et al., 2011; Sansores-Garcia et al., 2011). Our results in this report also demonstrate that Msn can respond to these manipulations and regulate Wts and Yki. Therefore, food particle ingestion-induced stretching of midgut and regulation of the Msn pathway may provide an in vivo model for further investigation of mechanosensing in a live tissue.

It is intriguing that EBs as a smaller population of cells in the midgut epithelium appear to have such an important role in mechanosensing. Our previous report (Li et al., 2014) and this report show a strong phenotype when using the EB driver and a weak phenotype when using the EC driver for both Msn and Tao. Moreover, there is clear Msn and Tao in vivo expression in precursor cells, but not detectable in ECs, in the knockin lines. The upd3-lacZ reporter staining is frequently detectable in EBs, as well as in ECs. All these are consistent with our model that Msn in EBs, and probably Hpo in ECs, are regulating upd3 expression in the two cell types (see Figure 1A). While EBs may be a smaller population, the number and size start to increase when Upd3/JAK/STAT is active (Zhou et al., 2013). In addition, a recent report (Antonello et al., 2015) proposed that EBs have elaborate cellular protrusions to monitor their surroundings and that, when they detect changes in tension and mechanical forces, this may promote differentiation and integration of the epithelium. Another more recent report demonstrates that the Piezo calcium channel expressing in pre-EE has a role in gut mechanosensing (He et al., 2018). One may imagine that food particle-induced mechanical stretching of the epithelium can directly affect both the ECs and the underlying EBs and EEs. Future investigation should help to integrate the function of all these cell types and pathways in this in vivo mechanosensing system.

Total parenteral nutrition, which means feeding via only intravenous infusion, in human patients and mammalian models causes intestinal atrophy (Brinkman et al., 2012; Rubin and Levin, 2016). Because food ingestion promotes adaptive growth of the intestine, it is possible that the lack of food particle-induced mechanical stretching of the epithelium contributes to the atrophy during total parenteral nutrition. Therefore, our results suggest that inhibiting the Msn/MAP4Ks family or promoting Yki/YAP activity may allow better intestinal growth to help the recovery of patients suffering from intestinal atrophy.

STAR★METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Tony Ip (tony.ip@umassmed.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Drosophila Stocks and Genetics

The cornmeal fly food was used to maintain regularly the fly stocks, unless indicated for specific feeding experiments. The fly food was prepared using 6.5 g/L agar, 23.5 g/L brewer’s yeast, 60 g/L cornmeal, and 60 ml/L molasses. These ingredients were added into the boiling water one by one, and then the mixture was heated continuously until fully cooked. After cooling down for 20–30 minutes, additional Tegosept Solution and Acid Mix were added before pouring into plastic vials or bottles.

For fly husbandry, the fly stocks were maintained in food vials or bottles and were transferred after 3 weeks if they were kept at room temperature, and after 5 weeks if they were kept at 18°C. Fly crosses for genetic experiments were maintained at room temperature, and shifted to the specified temperature when the offsprings were ready. Approximately 10 virgin females and 2–5 males per vial were used for setting up genetic crosses. To maximize the quantity of progeny, each cross was brooded every 4 days and some dry yeast was added into new vials.

It is noteworthy that the yeast in the fly food was meant to provide yeast extract as nutrients and the cooked particles were embedded in agar, cornmeal and molasses, therefore probably not so readily available for ingestion by the flies. In comparison, the live yeast feeding experiment for gut induction included 200 g/L (20% w/v) of yeast paste mixed in water directly available to flies ad lib. Therefore, after yeast paste feeding, the midguts of the flies were clearly distended. Moreover, their levels of upd3 mRNA by PCR and expression of upd3-lacZ reporter were significantly higher than those flies that were kept in water feeding or in regular food.

Either UAS-mCD8GFP or w1118 were used as wild type stocks where appropriate for crossing with various Gal4 and mutant lines for control experiments. The transgenic RNAi fly stocks used are as listed in the Key Resources Table. Transgenic flies when needed were generated in the w1118 background by Rainbow Transgenic Flies, Inc. (Camarillo, CA). Female flies were used for routine gut dissection, because of the bigger size.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse anti-HA-HRP (Clone 12CA5) | Roche | Cat# 11666606 001; RRID:AB_514506 |

| Mouse anti-FLAG (Clone M2) | Sigma | Cat# F1804; RRID:AB_262044 |

| Mouse anti-myc (Clone 9B11) | Cell signaling | Cat# 2276S; RRID:AB_331783 |

| Mouse anti-V5 | Invitrogen | Cat# R960–25; RRID:AB_2556564 |

| Mouse anti-beta-tubulin (Clone 2 28 33) | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 32–2600; RRID:AB_2533072 |

| Rat anti-RFP (Clone 5F8) | Chromotek | Cat# 5F820; RRID:AB_2336064 |

| Mouse anti-GFP (Clone C163) | Zymed | Cat# 33–2600; RRID:AB_2533111 |

| Mouse anti-Armadillo (Clone N2 7A1) | DSHB | N2 7A1; RRID:AB_528089 |

| Mouse anti-lacZ (Clone 40–1a) | DSHB | 40–1a; RRID:AB_528100 |

| Rabbit anti-pH3 | Abeam | Cat# ab5176; RRID:AB_304763 |

| Mouse anti-MINK1/TNIK (Clone 53) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 612250; RRID:AB_399573 |

| Rabbit anti-MINK1 | Bethyl | Cat# A302–191A; RRID:AB_1659821 |

| Rabbit anti-Yki | Dr. Duojia Pan (UT Southwestern) | Dong et al., 2007 |

| Rabbit anti-Yki-pS168 | Dr. Duojia Pan (UT Southwestern) | Dong et al., 2007 |

| Rabbit anti-Wts-pT1077 | Dr. Duojia Pan (UT Southwestern) | Yin et al., 2013 |

| Rabbit anti-pT194/pT187 | Dr. Qi Wang (Pfizer) | Wang et al., 2016 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Reoombinant Proteins | ||

| Okadaic Acid | Cell Signaling | Cat# 5934 |

| Latrunculin B | MP Biomedicals | Cat# 02159800 |

| Whole Glucan Particles (WGB) soluble | InvivoGen | Cat# tlrl-wgps |

| Polybead(R) Polystyrene Dyed Microspheres | Polysciences | Cat# 24292 |

| Glucan Particles | Dr.Gary Ostroff (UMass Medical School) | Young et al., 2007 |

| Protease inhibitor | Promega | G653A |

| Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 | Sigma | Cat# P5726 |

| Phos-tag™ Acrylamide | Wako Chemical | Cat# AAL-107 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| iScript cDNA Synthesis Kits | Bio Rad | Cat# 1708891 |

| iTaq™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix | Bio Rad | Cat# 1725124 |

| MEGAscript™ T7 Transcription Kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# AMB13345 |

| 0.5kPa Hydrogels coated 6 well plate | Softwell | Cat# SW6-Col-0.5 |

| Pierce™ Anti-HA Magnetic Beads | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 88837 |

| Anti-GFP mAb-Magnetic Beads | MBL | Cat# D153–11 |

| Pierce™ ProteinG Magnetic Beads | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 88847 |

| Glutathione SepharoseTM 4B | GE Healthcare | Cat# 17-0756-01 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

|

D. melanogaster: Cell line S2 DGRC Cat# 6, RRID:CVCL_Z232 |

Dr. Neal Silverman (UMass Medical School) | Flybase: FBtc0000006 |

|

D. melanogaster: Cell line S2R DGRC Cat# 150, RRID:CVCL_Z831 |

Dr. Neal Silverman (UMass Medical School) | Flybase: FBtc0000150 |

| D. melanogaster: Cell line KC167 | Dr. Neal Silverman (UMass Medical School) | Flybase: FBtc0000001 |

| Human HEK293 | Dr. Junhao Mao (UMass Medical School) | N/A |

| Yeast NKY278 (SK-1) for sporulation | Dr. Craig Peterson (UMass Medical School) | http://depts.washington.edu/younglab/yeastprotocolsfhtm)/strainsporulation.htm |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Dmel\w1118 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | FBal0018186 |

| Dme/\UAS-mCD8GFP | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BL32185 |

|

Dmel\msnRNAi P{KK108948}VIE-260B |

VDRC | V101517 |

|

Dme/\msnRNAi y[1] v[1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8]=TRiP.JF03219}attP2 |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | FBst0028791 |

|

Dmel\TaoRNAi W1118; p{GD8262} |

VDRC | V17432 |

|

Dmel\TaoRNAi P{KK108458}VIE-260B |

VDRC | V107645 |

| Dme/\upd3RNAi w[1118]; P{GD6811} |

VDRC | V27136 |

| Dme/\upd3RNAi y[1] v[1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8]=TRiP.HM05061}attP2 |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | FBst0028575 |

|

Dmel\TaoRNAi y[1] v[1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8]=TRiP.JF03119}attP2/TM3, Sb[1] |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BL31965 |

|

Dmel\msn-lacZ P{PZ}msn06946 |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | FBtiOO-05574 |

|

Dmel\UAS-wts-Myc w[*]; P{w[+mC]=UAS-wts.MYC}2/CyO; |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BL44250 |

| Dme/\UAS-FLAG-hpo y[1] w[*]; wg[Sp-1]/CyO; P{w[+mC]=UAS-dMST.FLAG}3/TM2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BL 44254 |

| Dme/\UASp-FLAG-Tao | Dr.Richard Fehon (University of Chicago) | Boggiano et al., 2011 |

| Dme/\Taoki-VENUS | Dr. Kieran Harvey (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre) | Poon et al., 2016 |

| Dme/\hpoki-VENUS | Dr. Kieran Harvey (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre) | Poon et al., 2016 |

| Dmel\UAS-MsnWT | This paper | N/A |

| Dme/\UAS-MsnK61R | This paper | N/A |

| Dme/\UAS-MsnT194A | This paper | N/A |

| Dmel\UAS-MsnT194E | This paper | N/A |

| Dmel\AUAS-Msn768,WT | This paper | N/A |

| Dme/\UAS-Msn768,K61R | This paper | N/A |

| Dme/\UAS-Msn768,T194A | This paper | N/A |

| Dmel\UAS-myr-MsnWT | This paper | N/A |

| Dme/\UAS-myr-MsnT194A | This paper | N/A |

| Deml\GFPki-Msn (On 3rd) | This paper | N/A |

| Dmel\Tao-kiRFP (on X) | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| msndsRNA | DRSC/TRiP | DRSC 37312, Data S1 |

| TaodsRNA | DRSC/TRiP | DRSC 19573, Data S1 |

| TaodsRNA | DRSC/TRiP | DRSC 28431, Data S1 |

| GFPdsRNA | DRSC/TRiP | DRSC 42734, Data S1 |

| Primers for rp49 qPCR Forward 5’ CGGATGGATATGCTAAGCTGT 3’ Reverse 5’ GCGCTTGTTCGATCCGTA 3’ |

This paper | Li et al., 2014 |

| Primers for upd3 qPCR Forward: 5’ GAGCACCAAGACTCTGGACA 3’ Reverse: 5’ CCAGTGCAACTTGATGTTGC 3’ |

This paper | Li et al., 2014 |

| Primers for Socs36E qPCR Forward: 5’ CAGTCAGCAATATGTTGTCG 3’ Reverse: 5’ ACTTGCAGCATCGTCGCTTC 3’ |

This paper | Li et al., 2014 |

| Guide RNA for GFPki-Msn Sense 5’ CTTCGTCCATCGGTCAACTGTTCAC 3’ Anti-sense 5’ AAACGTGAACAGTTGACCGATGG 3’ |

This paper | N/A |

| Guide RNA for Tao-kiRFP 1st sense 5’CTTCGCCGAGAAGCCTATGCAGATG 3’ 1st antisense 5’AAACCATCTGCATAGGCTTCTCGGC 3’ 2nd sense 5’ CTTCGTAAACACTTGTTGTGGGGGT 3’ 2nd antisense 5’ AAACACCCCCACAACAAGTGTTTAC 3’ |

This paper | N/A |

| Reoombinant DNA | ||

| pUAST-HA-MsnWT | This paper | Li et al., 2014 |

| pUAST-HA-MsnK61R | This paper | Li et al., 2014 |

| pUAST-HA-MsnT194A | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-HA-MsnT194E | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-HA-MsnT194E,K61R | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-HA-Msn768WT | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-HA-Msn768K61R | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-HA-Msn768T194A | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-myr-HA-MsnWT | This paper | Kaneko et al., 2011 |

| pUAST-myr-HA-MsnT194A | This paper | Kaneko et al., 2011 |

| pCMV-HA-MINK1WT | This paper | Kaneko et al., 2011 |

| pCMV-HA-MINK1k54R | This paper | Kaneko et al., 2011 |

| pCMV-HA-MAP4K4WT | This paper | Kaneko et al., 2011 |

| pCMV-myr-HA-MAP4K4WT | This paper | N/A |

| pCMV-myr-HA-MAP4K4T187A | This paper | N/A |

| pMIPZ-TaoK1-SBP-FLAG | This paper | N/A |

| pUASp-FLAG-Tao | Dr.Richard Fehon (University of Chicago) | Boggiano et al., 2011 |

| pUAST-FLAG-TaoWT | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-FLAG-TaoK56R | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-myr-FLAG-TaoWT | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-myr-FLAG-TaoK56R | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-HA-Msn328WT | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-myc-Wts | Dr. Jin Jiang (UT Southwestern) | Jia et al., 2003 |

| pUAST-FLAG-Hpo | Dr. Jin Jiang (UT Southwestern) | Jia et al., 2003 |

| pAC5.1-V5-WtsWT | Dr. Duojia Pan (UT Southwestern) | Yin et al., 2013 |

| pAC5.1-V5-WtsT1077A | Dr. Duojia Pan (UT Southwestern) | Yin et al., 2013 |

| pGEX-FLAG-WtsCWT | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-FLAG-WtsCT1077A | This paper | N/A |

| pUAST-Wts1-V5 | Dr. Kieran Harvey (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre) | Degoutin et al., 2013 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ 1.47V | NIH Image/lmageJ | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

Tissue Culture and Transfection

Drosophila S2, S2R and KC167 cells were cultured in Schneider media supplemented with 10% FBS and transfected with Effectene (Qiagen). These culture cells were originally derived from embryos and the sex was not known. For soft substrate experiment, 24 hours after transfection the S2R cells were reseeded onto 0.5KPa Hydrogels bounded 6 well plates (Matrigen, Brea, CA) or regular flat tissue culture 6 well plates for 12 hours. The KC167 cells were treated with latrunculin B (MP Biomedicals 02159800) at 0.2–0.5 μM 1 hour before lysing the cells. HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in Opti MEM Medium. Okadaic acid (OA) (Cell Signaling 5934S) treatment experiment in S2 cells was as described previously (Kaneko et al., 2011).

METHOD DETAILS

Plasmid Constructs

Constructs that expressed the HA-tagged MsnWT, MsnK61R, MsnT194A, MsnT194E, myr-MsnWT, myr-MsnT194A and truncated Msn768WT, Msn768,K61R, Msn768,T194A were generated in pBS cloning vector similar to that described (Kaneko et al., 2011; Li et al., 2014) and then subcloned into the pUAST vector using the EcoRI and XbaI sites. The human HA-MINK1 constructs were as described (Kaneko et al., 2011). HA-MINK1T187A and HA-MINK1K54R were generated on this constructs using Site-Directed Mutagenesis. The Flag-Tao is a gift from Dr. R. Fehon (University of Chicago), the Myc-Wts and Flag-Hpo were generously provided by Dr. Jin Jiang (UT Southwestern) and the V5-WtsT1077A point mutation was obtained from Dr. DJ Pan (UT Southwestern). The UAS-Wts1-V5 plasmid was provided by Dr. Kieran.Harvey (Peter MacCallum Cancer Center, Australia). The kinase domain of Msn and c-terminal of Wts fragment were sub-cloned into pGEX vector for the expression of GST fusion protein. The mouse TaoK1-SBP-Flag constructs was generated in pcDNA4-TO-Hygromycin-sfGFP vector and then subcloned into pMIPZ expression vector using the NheI and NotI site. The synthesis of msndsRNA (37312), TaodsRNA (19573 and 28431) and GFPdsRN followed the standard protocol from Drosophila RNAi Screening Center (DRSC).

GFP-knockin at the msn Locus and RFP-knockin at the Tao Locus

The GFPki-Msn expressing fly strain was generated in w1118 background based on the CRISPR /Cas9-mediated genome editing by homology-dependent repair using one guide RNA and a plasmid donor. One pair of guide RNA was designed as below: sense oligo 5’-CTTCGTCCATCGGTCAACTGTTCAC and antisense oligo 5’-AAACGTGAACAGT TGACCGATGG. The cutting site is 43 base pair after the ATG initiation codon. This annealed oligos for the guide RNA was cloned into the pDCC6 vector at the BsaI site (Gokcezade et al., 2014). Meanwhile, the donor with GFP sequence immediately after the ATG and approximately 1 kb genomic sequence each for the homology arms on both side of the ATG was cloned into the pUC57-Kan vector. The guide RNA and donor plasmids were co-injected into the w1118 embryos. The hatched offspring was screened by PCR of genomic DNA from individual flies for the GFP sequence and each positive strain was further confirmed by PCR around the msn locus and sequencing. Similarly by using the CRISPR /Cas9 genome editing method, the RFP-flox-hs-w+-flox sequence was introduced into the Tao locus and replaced the endogenous stop codon of Tao. Two pairs of guide RNA were used as below: 1st sense oligo 5’- CTTCGCCGAGAAGCCTATGCA GATG and 1st antisense oligo 5’- AAACCATCTGCATAGGCTTCTCGGC ; 2nd sense oligo 5’- CTTCGTAAACACTTGTTGTGGGGGT and 2nd antisense oligo 5’- AAACACCCCCACAACAAGTGTTTAC. Then the flox-w+-flox fragment was removed by crossing the positive candidate offsprings, which were red eyes with an allele carrying the Cre recombinase. Both of GFPki-Msn and Tao-kiRFP were designed and generated together with WellGenetics (Taiwan, R.O.C.).

Feeding Experiments

Newly hatched females within 6 hours were collected and maintained on regular yeast extract /cornmeal /molasses/agar food vials at room temperature for 5–7 days. They were then transferred to 29°C for 2 days for the transgenic construct to express and then subject to feeding. Before the feeding experiments, the flies were put in to the empty plastic vial for 2 hours to reduce the remaining food and liquid in the gut. Flies were kept at 29°C during starving and feeding. Yeast feeding contained 20% w/v in water with active yeast, heating killed yeast (100°C 30 min) or yeast spores added to the bottom of empty plastic vials. For yeast spores, NKY278 (SK-1) super-sporulation strain was used to prepare the spores. Fresh overnight grown yeast was added to the pre-sporulation medium (1% YPA) and cultured for approximately 24 hours at 30°C. After washing with water for 2 times, the yeast was resuspended in sporulation medium (CSH spo) and incubated at 30°C for 48 hours. 97% of the yeast examined under microscope were spores. For yeast particle feeding, the yeast glucan particles generated after multiple extraction was mixed with water at 250 mg/ml and that would be a similar molar concentrate as whole yeast experiments. The composition of extracted glucan particles on a weight basis is: carbohydrate 88%, protein <1%, Fat <1%, Ash 5%, moisture 7% (Young et al., 2007). For soluble food feeding experiments, animals were kept in empty plastic vial plus filter paper soaked with water, 5% sucrose, 5% apple juice, 5% yeast extract, 0.2 mg/ml whole glucan particle soluble (InvivoGen tlrl-wgps), 0.5 mg/ml laminarin (Sigma L9634), 25.1 mM total available nitrogen of essential amino acids and 0.1 g/liter of lipids (Grandison et al., 2009). Latrunculin B was incorporated with 5% sucrose or 20% yeast paste at 2 μM final concentration before feeding. The polystyrene particles used for the feeding is 3.00 Micron Ploybead® with black color (Polyscience, 24292). The feeding periods were 12 hours for MsnT194 phosphorylation detection by Western blots, 2 days for real time qPCR analysis, or 3 days for p-H3 staining, or as indicated in the figure legend.

Immunoprecipitation of Extracts from Culture Cells and Fly Guts

The endogenous MINK1 in HEK293 cells was immunoprecipitated by purified mouse anti-TNIK/MINK1 (BD Biosciences 612250) antibody and then blotted by rabbit anti-MINK1 antibody (Bethyl A302–191A). The Immunoprecipitation was followed by the protocol as described (Kaneko et al., 2011). The Immunoprecipitation of HA tagged Msn full length protein by using ~200 guts or GFPki-Msn by using ~800 adult fly guts were harvested into the lysis buffer with 500nM OA, and then anti-HA (Pierce 88836) or anti-GFP (MBL D153–11) magnetic beads were used for the precipitation.

Immunostaining and Fluorescent Microscopy

Female flies were used for routine gut dissection, because of the bigger size, and staining and antibodies used were as described (Li et al., 2014). Regular confocal microscope image acquisition and processing were as described (Amcheslavsky et al., 2011). Briefly, the entire gastrointestinal tracts were dissected into PBS with 4% formaldehyde, and were fixed in this medium for 3 hr at RT. Subsequent rinses, washes, blocking and incubations with primary antibodies were done in the PBS solution containing 0.5% BSA, 2% normal horse serum and 0.1% Tween-20 at 4°C over night. Secondary antibodies were used in 1:1000 dilutions as follows: goat anti-mouse IgG or goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to either Alexa 488 or Alexa 555 (Molecular probes). The mounting medium (Vectorshield, Vector Lab) with DAPI was used after 3 times washing at RT. Images were taken by a Nikon Spinning Disk confocal microscope (UMass Medical School Imaging Core Facility) and the super resolution image was generated using the Super-Resolution Imaging (SIM) system in OMX group-MaPS Imaging Core of UMASS medical school.

Western Blotting

Western blots were performed as described (Kaneko et al., 2011; Paramasivam et al., 2011). Briefly, 10 flies guts were dissected into cold PBS and transferred immediately to the 1X SDS-loading buffer with protease inhibitor (Promega) and phosphatase inhibitor (Sigma). The protein samples were heated at 95°C for 10 mins, and after a spin down the lysate was fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane using a transfer protocol according to the Bio-Rad instruction. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in TBST for 1 hour, the membrane was washed once with TBST and incubated with first antibodies at 4°C for over night. Membranes were washed three times for 10 mins and incubated with a 1:10000 dilution of HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (Promega) for 1 h at RT. Blots were washed with TBST three times and the signal was developed by the ECL system (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The antibodies used for Western blots and cell staining are described in the Key Resources Table. The Yki-p-S168, Yki and Wts-p-T1077 antibodies were generous gifts from Dr. DJ Pan (UT Southwestern). The rabbit polyclonal pT194/pT187 antibody was raised against the phosphorylated peptide NH2- GRRN(pT)FIGTPC-CONH2 and purified by protein G and 2 steps of peptide-affinity columns with non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated peptides, and 1:1000 was used for Western blot (Wang et al., 2016).

In Vitro Kinase Assay

The GST fusion proteins were induced by 0.1mM IPTG for 2 hours in E.coli, followed by the standard purification protocols using Glutathione Sepharose™ 4B (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After dialysis using the Slide-A-Lyzer™ cassette (Pirece), the purified GST fusion protein substrate was incubated with the kinase, which was precipitated from the lysate of S2 cells, in the reaction buffer with 200 uM ATP for 30 min at 30°C. Then the 4X SDS sample buffer was added to the reaction system directly for Western blot assay.

Real-Time qPCR

For real time quantitative PCR, total RNA was isolated from 10 dissected female guts, and 1ug RNA was used to prepare the cDNA accroding the manufacturer’s protocols (Bio-Rad, iScript cDNA Synthesis Kits). The quantitative PCR was performed in duplicate from each condition of at least 3 independent biological samples using iQ5 System (Bio-Rad). The ribosomal protein 49 (rp49) gene was used as the internal control for normalization of cycle number. Real time quantitative PCR protocol and primers can also be found in a previous report (Li et al., 2014) and in the Key Resources Table.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Three or more experiments using individual biological samples were performed for each of the experimental results presented in this report. The n in each figure represents the number of gut or cells counted in each experimental data point. For all statistics in this report, the error bar is standard error of the mean, and p value is from Student’s T-test: * is p<0.05, ** is p<0.01, NS is no significance with p>0.05.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Ingested particles expand the gut and reduce Misshapen membrane association

Mechanical properties change Misshapen membrane association and phosphorylation

Reduced membrane association of Misshapen decreases its T194 phosphorylation by Tao

Misshapen T194 phosphorylation is a control switch for regulating Warts-Yorkie

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) were used in this study. We also acknowledge the Vienna Drosophila Research Center for transgenic RNAi lines. We thank Craig Peterson for help with the yeast sporulation experiment, Richard Adshead for help with the Super-Resolution Microscope, Kieran Harvey for the Wts1 plasmid and Tao-kiVenus and Hpo-kiVenus flies, Richard Fehon for the Tao constructs, and D.J. Pan for the Yki antibodies. Y.T.I. is supported by NIH grants (DK083450, GM107457) and is a member of the UMass DERC (DK32520), a member of the UMass Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UL1TR000161), a member of the Guangdong Innovative Research Team Program (no. 201001Y0104789252), and a member of the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (no. 201704030044). J.M. is supported by an NIH grant (DK099510).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes five figures and one data file and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2018.04.014.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Amcheslavsky A, Ito N, Jiang J, and Ip YT (2011). Tuberous sclerosis complex and Myc coordinate the growth and division of Drosophila intestinal stem cells. J. Cell Biol 193, 695–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amcheslavsky A, Jiang J, and Ip YT (2009). Tissue damage-induced intestinal stem cell division in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell 4, 49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amcheslavsky A, Song W, Li Q, Nie Y, Bragatto I, Ferrandon D, Perrimon N, and Ip YT (2014). Enteroendocrine cells support intestinal stem-cell-mediated homeostasis in Drosophila. Cell Rep 9, 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonello ZA, Reiff T, Ballesta-Illan E, and Dominguez M (2015). Robust intestinal homeostasis relies on cellular plasticity in enteroblasts mediated by miR-8-Escargot switch. EMBO J 34, 2025–2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyaz A, Li H, and Jasper H (2015). Haemocytes control stem cell activity in the Drosophila intestine. Nat. Cell Biol 17, 736–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biteau B, and Jasper H (2014). Slit/Robo signaling regulates cell fate decisions in the intestinal stem cell lineage of Drosophila. Cell Rep 7, 1867–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggiano JC, Vanderzalm PJ, and Fehon RG (2011). Tao-1 phosphorylates Hippo/MST kinases to regulate the Hippo-Salvador-Warts tumor suppressor pathway. Dev. Cell 21, 888–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman AS, Murali SG, Hitt S, Solverson PM, Holst JJ, and Ney DM (2012). Enteral nutrients potentiate glucagon-like peptide-2 action and reduce dependence on parenteral nutrition in a rat model of human intestinal failure. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 303, G610–G622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S, Dudzic JP, Li X, Collas EJ, Boquete JP, and Lemaitre B (2016). Remote control of intestinal stem cell activity by haemocytes in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 12, e1006089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, and Ip YT (2009). Pathogenic stimulation of intestinal stem cell response in Drosophila. J. Cell Physiol 220, 664–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cognigni P, Bailey AP, and Miguel-Aliaga I (2011). Enteric neurons and systemic signals couple nutritional and reproductive status with intestinal homeostasis. Cell Metab 13, 92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coluccio AE, Rodriguez RK, Kernan MJ, and Neiman AM (2008). The yeast spore wall enables spores to survive passage through the digestive tract of Drosophila. PLoS One 3, e2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero JB, Stefanatos RK, Scopelliti A, Vidal M, and Sansom OJ (2012). Inducible progenitor-derived Wingless regulates adult midgut regeneration in Drosophila. EMBO J 31, 3901–3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Navascues J, Perdigoto CN, Bian Y, Schneider MH, Bardin AJ, Martinez-Arias A, and Simons BD (2012). Drosophila midgut homeostasis involves neutral competition between symmetrically dividing intestinal stem cells. EMBO J 31, 2473–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degoutin JL, Milton CC, Yu E, Tipping M, Bosveld F, Yang L, Bellaiche Y, Veraksa A, and Harvey KF (2013). Riquiqui and minibrain are regulators of the hippo pathway downstream of Dachsous. Nat. Cell Biol 15, 1176–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpire E (2009). The mammalian family of sterile 20p-like protein kinases. Pflugers Arch 458, 953–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demitrack ES, and Samuelson LC (2016). Notch regulation of gastrointestinal stem cells. J. Physiol 594, 4791–4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]