Abstract

About 40 per cent of people living with HIV do not sufficiently adhere to their medication regimen, which adversely affects their health. The current meta-analysis investigated the effect of psychosocial interventions on medication adherence in people living with HIV. Databases were systematically searched, resulting in 43 included randomized controlled trials. Study and intervention characteristics were investigated as moderators. The overall effect size indicates a small to moderate positive effect (Hedges’ g = 0.37) of psychosocial interventions on medication adherence in people living with HIV. No evidence for publication bias was found. This meta-analysis study concludes that various psychosocial interventions can improve medication adherence and thereby the health of people living with HIV.

Keywords: HIV, medication adherence, meta-analysis, psychotherapy

The WHO (2016) estimated that by the end of 2014, 37 million people worldwide were living with HIV, and 2 million became infected that year. If the virus is not treated with medication, it attacks the immune system, which may result in various health problems, AIDS and eventually death (Bangsberg et al., 2001). Medication adherence is important in tackling this pandemic and promoting health in people living with HIV (PLWH). Effective drug treatment has made HIV a chronic rather than a lethal condition. However, it also introduced new challenges. HIV drug treatment involves taking pills daily and adhering to treatment is difficult for many PLWH.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is a combination of at least two, but usually three, antiretroviral drug classes that suppresses viral replication (Günthard et al., 2014). In addition, ART lowers the chances of transmission through sexual risk behaviour (Castilla et al., 2005), birth and breastfeeding (Kouanda et al., 2010) and prevents spreading of the HIV pandemic. Its introduction in 1996 provided PLWH with the chance to stop disease progression and lethality (Moore and Chaisson, 1999). Initially, treatment involved taking several pills daily and had many adverse effects. Nowadays, ART has less side effects and simpler pill regimens. These developments have increased treatment adherence (Nachega et al., 2014). Major remaining challenges are the daily dosing, lifelong treatment and side effects. A meta-analysis that included 84 studies conducted worldwide from 1999 to 2009 found that only 62 per cent of people on ART took their prescribed doses >90 per cent of the time (Ortego et al., 2011). Increasing medication adherence should be a focus in the HIV care.

Non-adherence to ART is associated with mental health problems and psychological stressors such as depression (Gonzalez et al., 2011), life events (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2013), substance abuse (Lucas, 2011) and anxiety (Safren et al., 2003). A meta-analysis found that psychological factors are among the strongest correlates of non-adherence, stronger than other factors, for example, pill burden (Langebeek et al., 2014). Furthermore, mental health problems are highly prevalent in PLWH; the prevalence of depression is about 34 per cent, and of anxiety 28 per cent (Lowther et al., 2014). The way in which mental health problems and non-adherence are related is complex. Some antiretroviral drugs can have side effects such as mood changes, depression and anxiety. In turn, PLWH with mental health problems may have more difficulty adhering, because of cognitive or behavioural problems, for example, fatigue, hopelessness, lowered motivation and concentration (Wagner et al., 2011).

Like physical and mental health, sexual health is related to ART. ART non-adherence has been linked to more sexual risk taking, for example, having unprotected sex and greater risk of transmission. Depression, sexual risk behaviour and adherence may be related: it was found that depression leads to less ART adherence and condom use (Wagner et al., 2012). Non-adherence may also be related to lower socioeconomic status, such as lower income and education, and more unemployment. However, not all studies support this relationship (Falagas et al., 2008). Psychosocial interventions may influence vulnerabilities in socioeconomic status physical, mental and sexual health.

It is important to treat medication non-adherence in PLWH, because optimal adherence should improve PLWH’s health and well-being, and lower transmission risks. Treatments that do not address mental health problems as possible causes of non-adherence may be less effective than those that do. For instance, medication reminder devices focus on forgetfulness rather than mental health and have shown inconsistent effectiveness (Wise and Operario, 2008). In contrast, antidepressant treatments for PLWH consistently increase ART adherence (Springer et al., 2012). However, psychopharmacological treatment may cause side effects (e.g. reduced libido and inorgasmia), drug interaction and increased pill burden, which predict lower adherence and worse virologic suppression (Nachega et al., 2014). Therefore, psychosocial treatments may be preferred to treat non-adherence in PLWH.

Psychosocial interventions are primarily focussed on psychological or social factors, instead of purely focussing on medical factors such as pharmacological treatment or exercise (Ruddy and House, 2005). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses that investigated the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions on ART adherence, such as motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), peer support or counselling, have found promising but inconsistent results. Most reviews (Hill and Kavookjian, 2012) and meta-analyses (Amico et al., 2006; Simoni et al., 2006; Sin and DiMatteo, 2014) found that psychosocial interventions may increase ART adherence. However, some reviews showed negative or mixed results (Charania et al., 2014; Mathes et al., 2013; Rueda et al., 2006). A limitation of these findings is that they are partly based on low-quality studies. Furthermore, some results come from systematic reviews that do not recombine the raw data.

In addition to investigating the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions, it is important to examine factors (moderators) that may influence it. First, treatment characteristics are factors of the therapy, such as duration. Knowledge about which treatment characteristics influence effectiveness positively may be used when designing interventions. Furthermore, study characteristics, such as the geographical and temporal context of data collection, may partially explain differences between studies. Previous reviews and meta-analyses found larger effects on ART adherence when interventions involved CBT components (Charania et al., 2014), more therapist training (Hill and Kavookjian, 2012), targeted adherence risk or difficulty groups (Amico et al., 2006) or people with more severe depression (Sin and DiMatteo, 2014), longer duration (Rueda et al., 2006; Sin and DiMatteo, 2014), individual setting (Rueda et al., 2006) and adherence measures with recall periods >7 days (Simoni et al., 2006).

The current meta-analysis investigated the effectiveness of various types of psychosocial interventions on medication adherence in PLWH. To promote the methodological quality of the meta-analysis and strength of the conclusions, only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included. Furthermore, the effects of study characteristics and treatment characteristics were investigated.

Method

Literature search and study selection

Published literature was searched on 5 November 2014 through the databases PsycInfo (EBSCOhost), Embase (Ovid) and Medline (PubMed). Search words were related to three categories; that is, words related to HIV, psychosocial interventions and ART adherence. An overview of the used search terms is provided in Supplement A. Trials were also identified in published review articles and meta-analyses. Unpublished studies were not included.

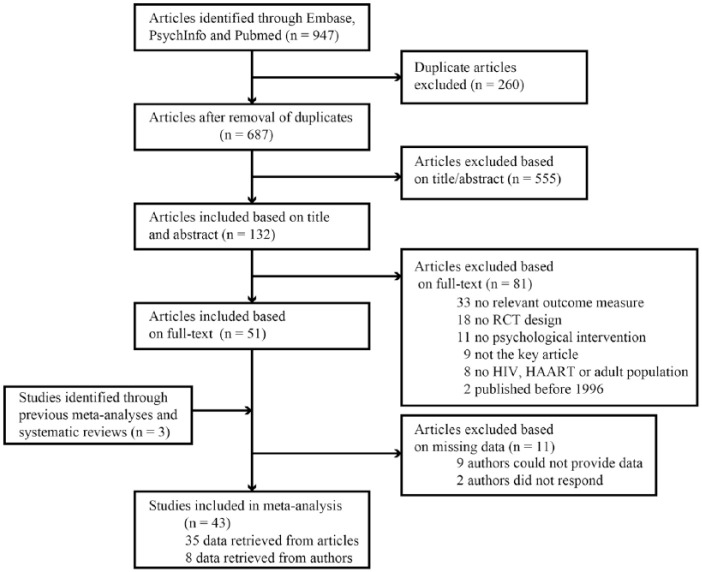

Database searches yielded 687 unique articles. Figure 1 shows the search and selection process. Titles and abstracts were reviewed, and if the article appeared to meet inclusion criteria (described below), its full text was retrieved. Then, a final selection was made based on their accordance with the inclusion criteria. This process resulted in 51 unique articles. Consulting previous review articles and meta-analyses resulted in another three articles. Data from 19 articles were not sufficient to calculate an effect size. The study authors were requested by e-mail to provide such data; eight authors provided the data (42%), nine replied but could not provide data (47%) and two could not be reached (11%). The final analysis included 43 studies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating study identification, inclusion and exclusion.

The selection of the first 50 titles and abstracts was executed independently by two researchers (first and second authors). The interrater reliability for this selection indicated substantial agreement (Landis and Koch, 1977), κ = 0.63, p < .001. The rest of the studies were selected by the first author. In cases of uncertainty, the co-authors were consulted, and eligibility was discussed until consensus was reached.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they (a) used a randomized controlled design, (b) provided a psychosocial intervention, (c) provided the intervention post 1996, after development of ART, (d) included PLWH age ≥ 18 years, (e) reported ART adherence as outcome and (f) were published in English. For criterion (b), psychosocial interventions are defined as interventions primarily focussed on psychological or social factors, in contrast to treatments that focus purely on medical factors such as pharmacological treatment or exercise (Ruddy and House, 2005). Full-text articles’ eligibility was inspected in the order: (f), (d), (a), (c), (b) and (e).

Using these criteria, selected studies could overlap in terms of sample or data. Rules for addressing multiplicity were set a priori. First, if multiple articles reported on the same trial, the article with the most relevant outcome data (e.g. on the complete sample) was used to determine the effect size. Second, if a study researched multiple interventions and a control group, the most intensive intervention was used in the analysis. Third, when studies had multiple control groups, the control group most similar to standard care was used in the analysis. Studies including only active interventions, but no control group, were not included. If multiple outcome measures were used, the most precise or objective measure of adherence was selected (e.g. monitoring device).

Data coding

Data coding was conducted with an a priori developed protocol. Coding included effect size data and sample, study and intervention characteristics data. Ten studies were coded by two independent researchers (first and second authors). The percentage of agreement over 37 variables was 86 per cent, indicating acceptable agreement in most situations (Neuendorf, 2002). In case of disagreement, the article was consulted again. The first author coded the remaining studies.

Medication adherence was coded for the treatment and control group based on the average percentage of post-treatment ART adherence. When articles did not provide the statistics necessary to calculate the effect size (sample size, mean and standard deviation (SD) or mean difference, t-value or p-value), the authors were contacted by e-mail. When the data could be not obtained, studies were excluded.

Coding of study characteristics included study aim (increasing adherence or improving overall mental or physical health), location, type of control group (waiting list, standard care or active control group), measurement type (self-report, monitoring device or pill count), recall period of the measure (≤14 days, >14 days or no recall: monitoring devices or pill count), percentage retention (participants that were available at the post-treatment assessment), mean age of the sample, percentage of females, sexual orientation or identity (homosexual/gay, heterosexual/straight or bisexual), ethnicity (African American or Black, Caucasian or White and Hispanic or Latino), percentage of participants with AIDS, years since HIV diagnosis and type of risk group (general, risk group or difficulty group). The sample was considered an a priori risk group if known risk factors, for example, experiencing distress from side effects, were an inclusion criterion. The sample was considered an a priori difficulty group if problematic adherence was an inclusion criterion. Other samples were considered general PLWH groups. Standard care control groups usually consisted of consultations with a physician or nurse and short education on medication use and adherence (e.g. Basso et al., 2013). An active control group was an intensive control condition, for example, of similar duration (time-matched) or intensity (dose-matched) as the intervention.

The intervention characteristics included treatment type (CBT, peer/social support or counselling), provider (psychologist/psychiatrist, counsellor, nurse, peer, healthcare professional or other), setting (individual, group or both), treatment duration (1–5, 5–12, 12–30 hours) and use of cognitive and/or behavioural techniques, motivational interviewing and relaxation. An intervention was categorized as CBT if it involved treatment techniques aimed at behavioural and cognitive change. Peer or social support interventions included support through peers or others. Counselling interventions were non-directive or aimed at problem-solving or changing adherence motivation or behaviour. Treatment duration would originally be used in meta-regression to test a dose–response effect. However, meta-regression assumptions (normality and linearity) were not met. Therefore, it was transformed to a categorical variable.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 2 (CMA; Borenstein et al., 2005). Effect sizes were expressed as Hedges’ g, computed with the standardized mean difference between the intervention and control group in average percentage of post-treatment medication adherence. Effect sizes of 0.2 were considered small, 0.5 medium and 0.8 large (Cohen, 1988). Reported p-values are two-tailed. The effect sizes were checked for outliers with standardized residuals >3. Outliers were transformed toward the mean (winsorized), so that they had a less disproportionate effect on the analyses. The effect sizes were winsorized to 3 SDs from the mean in the original direction (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001). Two positive outliers were found and transformed (DiIorio et al., 2008; Nyamathi et al., 2012).

Effect sizes were analysed using the random effects model. This model assumes heterogeneity across studies (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001). For moderator analyses, a mixed model was used. The random effects model combined the studies per subgroup. Because subgroups were assumed to be exhaustive, a fixed effects model combined the subgroup effects. Between-study variance was assumed to be similar across subgroups and was pooled. To examine heterogeneity between studies, the Q and I2 statistics were used. When Q is significant, this indicates important outcome differences across studies. I2 represents the amount of heterogeneity, where values of 25 per cent, 50 per cent and 75 per cent indicate low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins et al., 2003). Unfortunately, CMA version 2 does not allow post hoc multiple comparisons. If a significant moderator analysis compares more than two subgroups, it is unclear which subgroups differ from each other. In these cases, confidence intervals (CIs) were inspected to interpret differences.

Trim-and-fill analysis and Egger’s regression were conducted to test for publication bias. Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim-and-fill analysis estimates the amount of missing studies due to publication bias and the effect size when correcting for it. Egger’s regression tests whether the intercept statistically differs from 0, indicating publication bias (Egger et al., 1997).

Results

Study characteristics

The 43 studies included 5095 participants recruited from 1997 to 2013. Key characteristics per study are presented in Supplement B. Almost two-thirds of the participants were male (65%). Study samples ranged from 33 to 249 participants. Most studies were conducted in the United States (35/43) and the rest in Brazil, China, India, Kenya, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Spain and Switzerland. Participant’s average age was 42 years (k = 42, pooled SD = 8.9, k = 37; the discrepancy in the amount of studies is due to reporting differences). In studies that reported on the sexual orientation or identity of their sample, most participants described themselves as heterosexual or straight (38%, k = 17), homosexual or gay (35%, k = 13) and some as bisexual (8%, k = 13). Regarding ethnicity, the authors reported that 45 per cent of participants self-identified as Black or African American (k = 35), 35 per cent as White or Caucasian (k = 34) and 21 per cent as Latino or Hispanic (k = 25). The average time of HIV infection at baseline was 10 years in the 18 studies that reported on it (pooled SD = 6.8, k = 14) and 41 per cent of participants had AIDS (k = 11). Forty percent of studies focussed on at-risk populations (17/43), 42 per cent on adherence difficulties’ populations (18/43) and 19 per cent screened neither on risk factors nor difficulties (8/43).

Study aim was mostly increasing adherence (28/43) and sometimes improving (mental) health (15/43). Adherence was mostly measured with self-report (21/43) or a monitoring device (19/43), and rarely by pill count (3/43). Eleven self-report studies had recall periods ≤2 weeks; 10 had longer periods. Control groups frequently received standard care (28/43) and sometimes more active interventions (9/43). Alternatively, participants were put on a waiting list (6/43). The average percentage of retention was 83 per cent in treatment groups and 84 per cent in control groups (k = 41).

Intervention characteristics

In all, 22 studies investigated the effectiveness of counselling, 15 investigated CBT and 6 peer support. Cognitive and/or behavioural techniques were used in 58 per cent of interventions (25/43), motivational interviewing in 40 per cent (17/43) and relaxation in 19 per cent (8/43). Most interventions were provided individually (32/43), some in group format (7/43) or a combination (4/43). All interventions except one were provided in an outpatient setting. Interventions were provided by psychiatrists or psychologists (10/43), counsellors (4/43), nurses (8/43), peers (7/43), healthcare professionals (case or social workers, 9/43) or other (including online interventions; 5/43).

Treatment duration could be estimated for 33 studies (77%). An outlier was removed from this analysis because the study was unique in terms of setting and an extreme, influential outlier (Margolin et al., 2003). Its treatment duration was 104 hours and it was the only study with an inpatient setting. The average treatment duration in the rest of the studies was 8.15 hours (SD = 8.08, range: 1–30).

Main analysis

The random effects model meta-analysis of the overall sample (k = 43) resulted in a Hedges’ g effect size of 0.37 (95% CI (0.23, 0.52), p < .001). This indicates that average post-treatment medication adherence was higher in treatment than control groups, and the overall effect size was statistically different from 0. It shows a small to moderate positive effect of psychosocial interventions on medication adherence in PLWH. Figure 2 shows the effect size and 95 per cent CI per study in a forest plot.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the effect of psychosocial interventions on medication adherence.

The test of heterogeneity indicated significant between-study variance, Q(42) = 240.05, p < .001. The variance caused by effect differences between studies, rather than chance (I2 = 83%), was considerable (Higgins et al., 2003). This result supports the a priori choice of the random effects model and allows moderator analyses to explain heterogeneity.

Moderator analyses

Study characteristics explain some heterogeneity between studies, specifically the measurement type and recall period; see Table 1. Effect sizes were largest for studies measuring adherence by pill count; next were studies that used a monitoring device and the smallest effects were found for studies that used self-report measures. Unfortunately, the measurement type moderator analysis was unfit for further inferential interpretation; it included a subgroup based on three samples (pill count) and had incomparable CIs. Because the pill-count group was small, the results were influenced largely by a winsorized outlier, regardless of its transformation toward the mean (Nyamathi et al., 2012). Therefore, the results in Table 2 regarding measure type should be interpreted with caution. The moderator analysis with recall periods showed that studies with recall periods ≤14 days had smaller effect sizes than studies with no recall period. The studies with a recall period >14 days did not differ significantly from those with shorter or no recall periods. Study aim, population, type of control group and location did not moderate effect size, nor did intervention characteristics; see Table 2.

Table 1.

Overview of subgroup effect sizes and heterogeneity for study characteristics.

| Moderator | Subgroup | k | Hedges’ g | 95% CI | Q | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study aim | Increasing adherence | 28 | 0.44 | 0.25–0.62 | 1.34 | .25 |

| Improving health | 15 | 0.25 | −0.001 to 0.51 | |||

| Sample | General | 8 | 0.43 | 0.08–0.78 | 0.17 | .92 |

| Risk group | 17 | 0.38 | 0.14–0.63 | |||

| Difficulties’ group | 18 | 0.34 | 0.11–0.58 | |||

| Control group | Waiting list | 6 | 0.13 | −0.25 to 0.52 | 5.52 | .06 |

| Standard care | 28 | 0.33 | 0.14–0.51 | |||

| Active control group | 9 | 0.71 | 0.37–1.04 | |||

| Measure type | Self-report | 21 | 0.19 | −0.02 to 0.39 | 8.65 | .01* |

| Monitoring device | 19 | 0.49 | 0.28–0.71 | |||

| Pill count | 3 | 0.97 | 0.41–1.53 | |||

| Recall period | ≤14 days | 11 | 0.13 | −0.16 to 0.42 | 6.52 | .04* |

| >14 days | 10 | 0.25 | −0.05 to 0.54 | |||

| No recall | 22 | 0.55 | 0.35–0.75 | |||

| Location | United States | 35 | 0.32 | 0.16–0.49 | 2.09 | .15 |

| Other | 8 | 0.61 | 0.26–0.95 |

CI: confidence interval; k: number of studies; Q: between-group Q.

p < .05.

Table 2.

Overview of subgroup effect sizes and heterogeneity for intervention characteristics.

| Moderator | Subgroup | k | Hedges’ g | 95% CI | Q | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention type | CBT | 15 | 0.29 | 0.03–0.55 | 0.67 | .72 |

| Peer or social support | 6 | 0.45 | 0.05–0.85 | |||

| Counselling | 22 | 0.41 | 0.20–0.62 | |||

| CB | No | 18 | 0.49 | 0.27–0.72 | 1.83 | .18 |

| Yes | 25 | 0.29 | 0.09–0.48 | |||

| MI | No | 26 | 0.31 | 0.12–0.50 | 1.19 | .28 |

| Yes | 17 | 0.48 | 0.24–0.71 | |||

| Relaxation | No | 35 | 0.42 | 0.26–0.58 | 1.69 | .19 |

| Yes | 8 | 0.16 | −0.18 to 0.51 | |||

| Setting | Group | 7 | 0.11 | −0.26 to 0.48 | 2.47 | .29 |

| Individual | 32 | 0.41 | 0.24–0.59 | |||

| Combination | 4 | 0.52 | 0.02–1.03 | |||

| Therapy provider | Psychologist/psychiatrist | 10 | 0.39 | 0.07–0.71 | 3.37 | .64 |

| Counsellor | 4 | 0.35 | −0.15 to 0.84 | |||

| Nurse | 8 | 0.62 | 0.29–0.95 | |||

| Peer | 7 | 0.37 | 0.00–0.73 | |||

| Healthcare professional | 9 | 0.24 | −0.08 to 0.56 | |||

| Other | 5 | 0.21 | −0.22 to 0.63 | |||

| Treatment duration | Short | 16 | 0.40 | 0.15–0.64 | 1.13 | .57 |

| Medium | 8 | 0.29 | −0.06 to 0.65 | |||

| Long | 8 | 0.17 | −0.19 to 0.52 | |||

| Missing | 10 |

CB: cognitive and/or behavioural techniques; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; CI: confidence interval; k: number of studies; MI: motivational interviewing; Q: between-group Q.

Publication bias

Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill funnel plot showed that the studies in this meta-analysis are distributed symmetrically around the mean effect size. No studies were trimmed or filled, indicating no evidence of publication bias. Egger’s test of the intercept was not significant, intercept 1.02 (95% CI (−1.74, 3.78), t(41) = 0.75, p = .46. This also indicates that there is no publication bias.

Discussion

The results of the current meta-analysis show that psychosocial interventions have a small to moderate positive effect on medication adherence in PLWH. This finding has important implications because better ART adherence is related to disease suppression and lowers transmission risk. This effect is likely due to psychosocial interventions treating important causes of ART non-adherence. Those may include the psychological correlates found in an earlier meta-analysis, such as depressive symptoms, stigma and lack of social support. In addition to mental health, non-adherence is related to many factors including pill burden, side effects, physical health, sexual health and socioeconomic status. Psychosocial interventions may influence how PLWH cope with challenges in these fields. The findings of this study are in line with previous meta-analyses and reviews that have shown promising results for treatments involving behavioural components (Simoni et al., 2006), counselling (Amico et al., 2006), motivational interviewing (Hill and Kavookjian, 2012) and treatments aimed at depression (Sin and DiMatteo, 2014). Contrastingly, some reviews found negative or mixed results of psychosocial interventions aimed at improving adherence (Charania et al., 2014; Mathes et al., 2013; Rueda et al., 2006). This may be explained by the method; this study uses meta-analysis on 43 studies, while previous reviews did not combine the individual study data to determine an overall effect. In addition, two reviews had fewer studies than the current meta-analysis (Charania et al., 2014; Rueda et al., 2006). In terms of geographical and temporal context, previous reviews and meta-analyses were similar to the current meta-analysis and featured studies conducted post 1996 and mainly in the United States. In short, the results of this meta-analysis are in line with a number of previous studies and indicate that offering psychosocial interventions to PLWH may improve medication adherence.

Intervention characteristics did not explain differences in treatment effectiveness in this study. Therefore, findings that interventions were more effective when they included at-risk or adherence difficulty groups (Amico et al., 2006), involved CBT components (Charania et al., 2014), had longer treatment duration (Rueda et al., 2006; Sin and DiMatteo, 2014) or provided individual therapy (Rueda et al., 2006) were not replicated. The current meta-analysis results indicate that many different forms of psychosocial treatment in many different settings may be effective. The results are in accordance with the dodo bird verdict and common factors theory. These claim that various psychosocial interventions lead to similar outcomes, due to common effective factors such as therapeutic alliance (Laska et al., 2014).

Differences in methodology and included studies may explain differences in results regarding the moderating effect of intervention characteristics between this study and previous studies. It may be that moderating factors that seem effective in a systematic review, based on the number of studies with positive findings, were not found to be effective in this meta-analysis, based on pooled and weighted results. It could also be that such findings were not present in this sample because it is based on RCTs only, or because the sample consists of a various psychosocial interventions rather than, for instance, motivational interviewing alone. Another explanation might be that moderating effects of these characteristics are small and more studies are necessary to find subgroup differences.

Two study characteristics showed a relationship with treatment effectiveness: the type of adherence measure and its recall period. However, the measure type analysis included a subgroup of three studies, including one influential outlier, hence findings should be interpreted with caution. With this in mind, the results indicate that studies that used pill-count measures may have larger effect sizes than studies that used self-report measures. This suggests that pill-count measures are more sensitive to detect differences than self-report measures, which agrees with earlier findings (Sangeda et al., 2014). In addition, pill count and monitoring devices are more objective than self-report measures; they do not rely on the participant’s memory. Second, studies that used measures without recall period had larger effect sizes than those with recall. This may be associated with the previous result that pill-count measures, which have no recall period, have larger effect sizes than self-report measures, which have a recall period. Combining previous and current study findings, it seems that objective measures that do not rely on recall may be more sensitive to changes in adherence than subjective measures that rely on self-report. For future studies, researchers should keep in mind these possible sensitivity differences when deciding on a measurement method.

Strengths and limitations

This study combined and analysed the data of 43 studies meta-analytically, which resulted in high statistical power. In addition, a wide range of psychosocial interventions were included in this meta-analysis. This study adds to previous research by analysing results from RCTs only, which are considered high-quality studies in experimental psychology. Another strength is that results indicated no influence of publication bias. However, some studies that were identified during the systematic search were excluded due to missing data.

The study also had limitations. First, the study investigated only short-term post-treatment effects. Therefore, the long-term effectiveness of psychosocial interventions remains unclear. Second, some moderators had categories with few studies, making it hard to generalize their results. Third, the mechanisms of change remain unclear, as psychosocial interventions may influence factors related to adherence, such as physical, mental and sexual health, and socioeconomic status.

The current meta-analysis was influenced by limitations of the included studies and identified some gaps in the literature. First, most studies were conducted in the United States, leaving other locations greatly influenced by HIV, such as Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, underrepresented. The minority of women in the meta-analysis (35%) correspond with the ratio of women with HIV in the United States (Prejean et al., 2011) but not Sub-Saharan Africa (UNAIDS, 2014), where HIV disproportionally impacts women. Furthermore, outcomes, study and sample characteristics, such as mean age and ethnicity, were not always reported, which hindered coding. ART pill burden and side effects were often not reported, and thus not analysed. Standardized reporting could be improved by following CONSORT guidelines (Schulz et al., 2010).

Future research

It would be interesting to study common factors in psychosocial treatments, such as therapeutic alliance and empathy. Second, it would be interesting to investigate long-term effects of psychosocial treatments, to assess whether positive results can be retained. Since the intervention provider was not a significant moderator, future research could study the effectiveness of online interventions, which may be more accessible and cost-effective. Fourth, future research might focus on investigating the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in non-USA samples. Furthermore, studying factors that are related to high or consistent adherence, rather than non-adherence, might provide new insights for psychosocial interventions. Finally, since the effect size was small to moderate, research on supplemental strategies to increase adherence is recommended. The best result may be obtained by fine-tuning and combining medical and psychosocial treatments for PLWH.

Conclusion

This study adds to HIV care literature by establishing the positive effect of a wide range of psychosocial interventions on medication adherence in PLWH in the form of a meta-analysis of RCTs. Better medication adherence promotes the health of PLWH and impacts public health by lowering transmission risk. This study finds that various types of psychosocial interventions can be effective for various PLWH groups. It is important that healthcare professionals are made aware of this, so they can refer PLWH with adherence challenges. Increasing medication adherence in PLWH remains an important public health goal and can potentially help millions of people to suppress the virus and increase their well-being.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, JHP_SupplementA for Psychosocial interventions enhance HIV medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Pascalle Spaan, Sanne van Luenen, Nadia Garnefski and Vivian Kraaij in Journal of Health Psychology

Supplemental material, JHP_SupplementB for Psychosocial interventions enhance HIV medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Pascalle Spaan, Sanne van Luenen, Nadia Garnefski and Vivian Kraaij in Journal of Health Psychology

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all authors who shared their data for use in this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Pascalle Spaan  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1482-8311

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1482-8311

Vivian Kraaij  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1146-177X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1146-177X

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

*References of studies included in the meta-analysis are marked with an asterisk.

- Amico KR, Harman JJ, Johnson BT. (2006) Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: A research synthesis of trials, 1996 to 2004. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 41: 285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, et al. (2001) Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS 15: 1181–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Basso CR, Helena ET, Caraciolo JM, et al. (2013) Exploring ART intake scenes in a human rights-based intervention to improve adherence: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS and Behavior 17: 181–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, et al. (2005) Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, Version 2. Englewood, NJ: Biostat. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Chadwick C, Graci M. (2013) The connection between serious life events, anti-retroviral adherence, and mental health among HIV-positive individuals in the Western Cape, South Africa. AIDS Care – Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV 25: 1581–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Carrico AW, Antoni MH, Duran RE, et al. (2006) Reductions in depressed mood and denial coping during cognitive behavioral stress management with HIV-positive gay men treated with HAART. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 31: 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilla J, Del Romero J, Hernando V, et al. (2005) Effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 40: 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charania MR, Marshall KJ, Lyles CM, et al. (2014) Identification of evidence-based interventions for promoting HIV medication adherence: Findings from a systematic review of U.S.-based studies, 1996–2011. AIDS and Behavior 18: 646–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Chung MH, Richardson BA, Tapia K, et al. (2011) A randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of counseling and alarm device on HAART adherence and virologic outcomes. PLoS Medicine 8: e1000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Claborn KR, Leffingwell TR, Miller MB, et al. (2014) Pilot study examining the efficacy of an electronic intervention to promote HIV medication adherence. AIDS Care – Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV 26: 404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- *De Bruin M, Hospers HJ, van Breukelen GJP, et al. (2010) Electronic monitoring-based counseling to enhance adherence among HIV-infected patients: A randomized controlled trial. Health Psychology 29: 421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *DiIorio C, McCarty F, Resnicow K, et al. (2008) Using motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications: A randomized controlled study. AIDS Care – Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV 20: 273–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Duncan LG, Moskowitz JT, Neilands TB, et al. (2012) Mindfulness-based stress reduction for HIV treatment side effects: A randomized, wait-list controlled trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 43: 161–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, Tweedie R. (2000) Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56: 455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falagas ME, Zarkadoulia EA, Pliatsika PA, et al. (2008) Socioeconomic status (SES) as a determinant of adherence to treatment in HIV infected patients: A systematic review of the literature. Retrovirology 5: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Goggin K, Gerkovich MM, Williams KB, et al. (2013) A randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of motivational counseling with observed therapy for antiretroviral therapy adherence. AIDS and Behavior 17: 1992–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Golin CE, Earp J, Tien HC, et al. (2006) A 2-arm, randomized, controlled trial of a motivational interviewing-based intervention to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among patients failing or initiating ART. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 42: 42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, et al. (2011) Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 58: 181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günthard HF, Aberg JA, Eron JJ, et al. (2014) Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2014 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA Panel. JAMA 312: 410–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hersch RK, Cook RF, Billings DW, et al. (2013) Test of a web-based program to improve adherence to HIV medications. AIDS and Behavior 17: 2963–2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill S, Kavookjian J. (2012) Motivational interviewing as a behavioral intervention to increase HAART adherence in patients who are HIV-positive: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS Care – Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV 24: 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Holstad MM, DiIorio C, Kelley ME, et al. (2011) Group motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications and risk reduction behaviors in HIV infected women. AIDS and Behavior 15: 885–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Holstad MM, Essien JE, Ekong E, et al. (2012) Motivational groups support adherence to antiretroviral therapy and use of risk reduction behaviors in HIV positive Nigerian women: A pilot study. African Journal of Reproductive Health 16: 14–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Horvath KJ, Oakes JM, Rosser BR, et al. (2013) Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of an online peer-to-peer social support ART adherence intervention. AIDS and Behavior 17: 2031–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ingersoll KS, Farrell-Carnahan L, Cohen-Filipic J, et al. (2011) A pilot randomized clinical trial of two medication adherence and drug use interventions for HIV+ crack cocaine users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 116: 177–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Johnson MO, Charlebois E, Morin SF, et al. (2007) Effects of a behavioral intervention on antiretroviral medication adherence among people living with HIV: The healthy living project randomized controlled study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 46: 574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Johnson MO, Dilworth SE, Taylor JM, et al. (2011) Improving coping skills for self-management of treatment side effects can reduce antiretroviral medication nonadherence among people living with HIV. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 41: 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Kalichman MO, et al. (2011) Integrated behavioral intervention to improve HIV/AIDS treatment adherence and reduce HIV transmission. American Journal of Public Health 101: 531–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Konkle-Parker DJ, Amico KR, McKinney VE. (2014) Effects of an intervention addressing information, motivation, and behavioral skills on HIV care adherence in a southern clinic cohort. AIDS Care – Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV 26: 674–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Konkle-Parker DJ, Erlen JA, Dubbert PM, et al. (2012) Pilot testing of an HIV medication adherence intervention in a public clinic in the Deep South. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 24: 488–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouanda S, Tougri H, Cisse M, et al. (2010) Impact of maternal HAART on the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: Results of an 18-month follow-up study in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. AIDS Care – Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV 22: 843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kurth AE, Spielberg F, Cleland CM, et al. (2014) Computerized counseling reduces HIV-1 viral load and sexual transmission risk: Findings from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 65: 611–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33: 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langebeek N, Gisolf EH, Reiss P, et al. (2014) Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: A meta-analysis. BMC Medicine 12: 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laska KM, Gurman AS, Wampold BE. (2014) Expanding the lens of evidence-based practice in psychotherapy: A common factors perspective. Psychotherapy 51: 467–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. (2001) Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Lowther K, Selman L, Harding R, et al. (2014) Experience of persistent psychological symptoms and perceived stigma among people with HIV on antiretroviral therapy (ART): A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 51: 1171–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM. (2011) Substance abuse, adherence with antiretroviral therapy, and clinical outcomes among HIV-infected individuals. Life Sciences 88: 948–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Margolin A, Avants SK, Warburton LA, et al. (2003) A randomized clinical trial of a manual-guided risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive injection drug users. Health Psychology 22: 223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathes T, Pieper D, Antoine SL, et al. (2013) Adherence-enhancing interventions for highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients – A systematic review. HIV Medicine 14: 583–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RD, Chaisson RE. (1999) Natural history of HIV infection in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 13: 1933–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Murphy DA, Lu MC, Martin D, et al. (2002) Results of a pilot intervention trial to improve antiretroviral adherence among HIV-positive patients. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 13: 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachega JB, Parienti JJ, Uthman OA, et al. (2014) Lower pill burden and once-daily antiretroviral treatment regimens for HIV infection: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Infectious Diseases 58: 1297–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf KA. (2002) The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- *Nyamathi A, Hanson AY, Salem BE, et al. (2012) Impact of a rural village women (Asha) intervention on adherence to antiretroviral therapy in southern India. Nursing Research 61: 353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortego C, Huedo-Medina TB, Llorca J, et al. (2011) Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): A meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior 15: 1381–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Parsons JT, Golub SA, Rosof E, et al. (2007) Motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral intervention to improve HIV medication adherence among hazardous drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 46: 443–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. (2011) Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS ONE 6: e17502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rathbun RC, Farmer KC, Stephens JR, et al. (2005) Impact of an adherence clinic on behavioral outcomes and virologic response in treatment of HIV infection: A prospective, randomized, controlled pilot study. Clinical Therapeutics 27: 199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Dolezal C, et al. (2005) Couple-focused support to improve HIV medication adherence: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS 19: 807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Reynolds NR, Testa MA, Su M, et al. (2008) Telephone support to improve antiretroviral medication adherence: A multisite, randomized controlled trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 47: 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rosen MI, Dieckhaus K, McMahon TJ, et al. (2007) Improved adherence with contingency management. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 21: 30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddy R, House A. (2005) Psychosocial interventions for conversion disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD005331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda S, Park-Wyllie LY, Bayoumi AM, et al. (2006) Patient support and education for promoting adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD001442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Gershuny BS, Hendriksen E. (2003) Symptoms of posttraumatic stress and death anxiety in persons with HIV and medication adherence difficulties. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 17: 657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, et al. (2009) A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychology 28: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM, Bullis JR, et al. (2012) Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 80: 404–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Safren SA, Otto M, Worth JL, et al. (2001) Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: Life-Steps and medication monitoring. Behaviour Research and Therapy 39: 1151–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Samet JH, Horton NJ, Meli S, et al. (2005) A randomized controlled trial to enhance antiretroviral therapy adherence in patients with a history of alcohol problems. Antiviral Therapy 10: 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangeda RZ, Mosha F, Prosperi M, et al. (2014) Pharmacy refill adherence outperforms self-reported methods in predicting HIV therapy outcome in resource-limited settings. BMC Public Health 14: 1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. (2010) CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Annals of Internal Medicine 152: 726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Simoni JM, Huh D, Frick PA, et al. (2009) Peer support and pager messaging to promote antiretroviral modifying therapy in Seattle: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 52: 465–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Simoni JM, Pantalone DW, Plummer MD, et al. (2007) A randomized controlled trial of a peer support intervention targeting antiretroviral medication adherence and depressive symptomatology in HIV-positive men and women. Health Psychology 26: 488–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, et al. (2006) Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load. A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 43: S23–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Simoni JM, Wiebe JS, Sauceda JA, et al. (2013) A preliminary RCT of CBT-AD for adherence and depression among HIV-positive Latinos on the U.S.-Mexico border: The Nuevo Dia study. AIDS and Behavior 17: 2816–2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, DiMatteo MR. (2014) Depression treatment enhances adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 47: 259–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Sorensen JL, Haug NA, Delucchi KL, et al. (2007) Voucher reinforcement improves medication adherence in HIV-positive methadone patients: A randomized trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 88: 54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Dushaj A, Azar MM. (2012) The impact of DSM-IV mental disorders on adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among adult persons living with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior 16: 2119–2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Tuldra A, Fumaz CR, Ferrer Ma J, et al. (2000) Prospective randomized two-arm controlled study to determine the efficacy of a specific intervention to improve long-term adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 25: 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS (2014) Fact sheet 2014: Global statistics. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/factsheet/2014/20140716_FactSheet_en.pdf

- Wagner GJ, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Holloway IW, et al. (2012) Depression in the pathway of HIV antiretroviral effects on sexual risk behavior among patients in Uganda. AIDS and Behavior 16: 1862–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GJ, Goggin K, Remien RH, et al. (2011) A closer look at depression and its relationship to HIV antiretroviral adherence. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 42: 352–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wagner GJ, Kanouse DE, Golinelli D, et al. (2006) Cognitive-behavioral intervention to enhance adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A randomized controlled trial (CCTG 578). AIDS 20: 1295–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wagner GJ, Lovely P, Schneider S. (2013) Pilot controlled trial of the adherence readiness program: An intervention to assess and sustain HIV antiretroviral adherence readiness. AIDS and Behavior 17: 3059–3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Webel AR. (2010) Testing a peer-based symptom management intervention for women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care – Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV 22: 1029–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Weber R, Christen L, Christen S, et al. (2004) Effect of individual cognitive behaviour intervention on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: Prospective randomized trial. Antiviral Therapy 9: 85–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2016) HIV/AIDS: Fact sheet. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/en/

- *Williams AB, Wang H, Li X, et al. (2014) Efficacy of an evidence-based ARV adherence intervention in China. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 28: 411–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise J, Operario D. (2008) Use of electronic reminder devices to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A systematic review. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 22: 495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wyatt GE, Longshore D, Chin D, et al. (2004) The efficacy of an integrated risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive women with child sexual abuse histories. AIDS and Behavior 8: 453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, JHP_SupplementA for Psychosocial interventions enhance HIV medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Pascalle Spaan, Sanne van Luenen, Nadia Garnefski and Vivian Kraaij in Journal of Health Psychology

Supplemental material, JHP_SupplementB for Psychosocial interventions enhance HIV medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Pascalle Spaan, Sanne van Luenen, Nadia Garnefski and Vivian Kraaij in Journal of Health Psychology