Abstract

There is renewed optimism that the goal of developing a highly effective AIDS vaccine is attainable. The HIV-1 vaccine field has seen its first trial of a vaccine candidate that prevents infection. Although modest in efficacy, this finding, along with the recent discovery that the human immune system can produce broadly neutralizing antibodies capable of inhibiting greater than 90% of circulating viruses, provides a guide for the rational design of vaccines and protection by passive immunization. Together, these findings will help shape the next generation of HIV vaccines.

Keywords: clinical trials, HIV-1, immunogen design, vaccine

Introduction

There is arguably no greater scientific and public health challenge than the development of a preventive AIDS vaccine. Although alternative strategies such as behavioral interventions, topical microbicides, pre-exposure prophylaxis with antiretroviral therapy and early testing and treatment are progressing as prevention measures [1–4], these strategies are highly dependent on patient adherence, chronic treatment and early detection [5]. Because of its simple administration and potential for long-term protection, a highly effective HIV-1 vaccine remains the optimal approach for bringing an end to the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

HIV causes a lifelong persistent infection that quickly establishes viral reservoirs after the primary infection [6]. Thus, an effective vaccine must functionally sterilize and abort an impending infection, not merely control the virus after infection, a mechanism employed by many licensed vaccines. The development of an AIDS vaccine has represented a daunting challenge. In part, this is because HIV uses multiple mechanisms to escape the immune system. The high mutation rate, envelope (Env) heterogeneity, low spike density on the virion surface [7–9], Env glycosylation and conformational shielding of conserved epitopes all serve to evade recognition by neutralizing antibodies [10,11]. Thus, the type of immunity required for protection from HIV infection in humans has yet to be defined [12].

Despite these numerous mechanisms of evasion, a vaccine which elicits robust cellular and humoral immunity should prevent HIV-1 infection. Individuals that control HIV-1 infection without antiviral therapy possess CD8+ T lymphocytes capable of inhibiting HIV-1 replication in vitro [13–15]. Additionally, the isolation of potent, broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) from chronically infected individuals demonstrates that the human immune system can, in fact, generate such antibodies [16–18] and provide a starting point for immunogen design. These immune responses, particularly the appropriate humoral response, are guiding present efforts in vaccine development. The modest efficacy achieved in the RV144 trial also provided the first proof of concept for a preventive vaccine in humans and the first chance to define immune correlates of protection [19]. Here, we discuss alternative approaches to HIV-1 vaccine development, the status of HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trials and prospects for the next generation of HIV-1 vaccines.

Immunologic basis for preventive HIV-1 vaccines

The rationale for antibody vaccines

Effective HIV-1 vaccines will likely elicit both humoral and cellular immune responses (Fig. 1) [20,21]. Several observations have provided the rationale for pursuing antibody-based vaccination. Antibodies that can bind to the HIV-1 Env and prevent virus entry would provide the best chance for sterilizing protective immunity because the virus would not be able to enter target cells. Passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies into nonhuman primates (NHP) suggests that potent neutralizing antibodies are sufficient to protect against chimeric SIV/HIV (SHIV) infection [22,23], providing a proof of concept for sterilizing immunity. Also, antibodies could potentially inhibit HIV-1 through Fc-mediated effector functions such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent cellular virus inhibition (Fig. 1). However, the contribution of these responses to protection in vivo is still unclear [21].

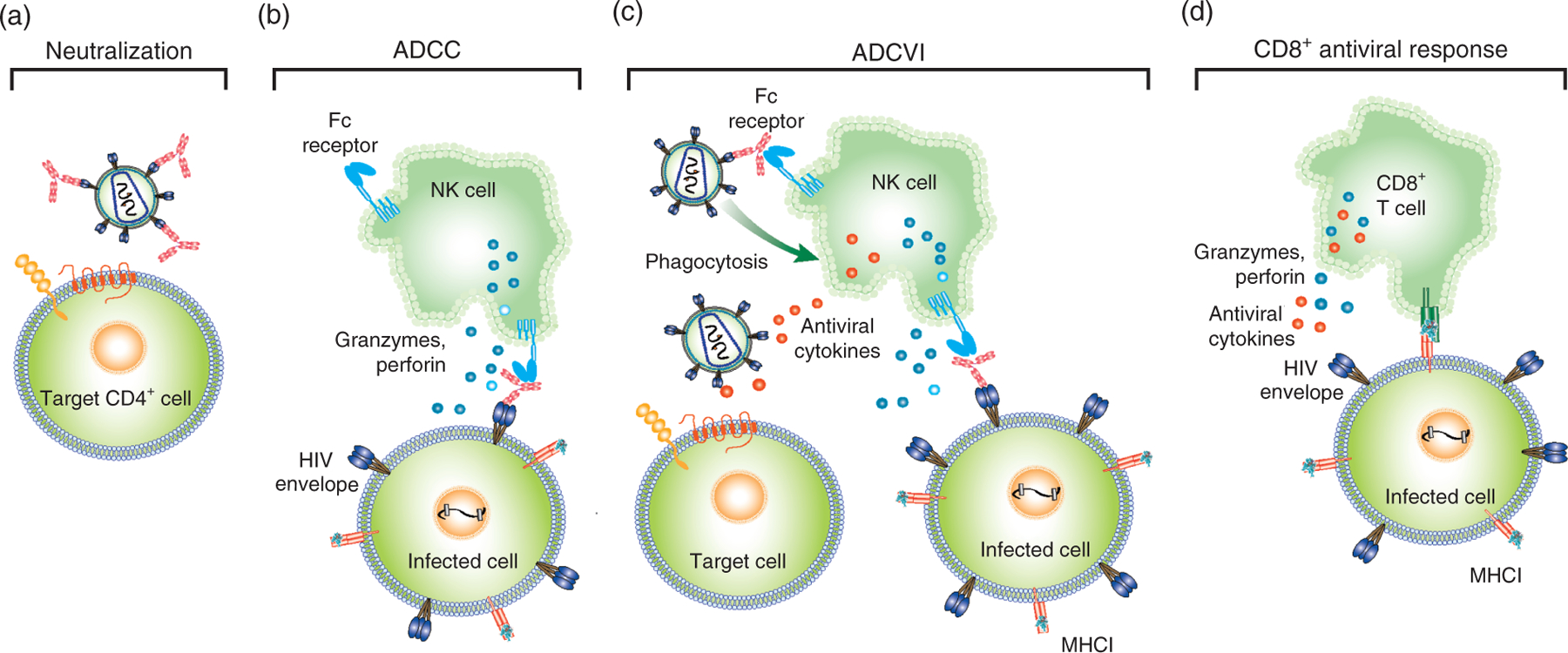

Fig. 1. Immune mechanisms of HIV-1 inhibition.

(a) Antibody neutralization of HIV-1. Antibodies (light red) directed against the HIV-1 envelope (Env) trimer (blue and brown) prevent infection by blocking HIV-1 entry into target cells. (b) Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) is mediated by antibodies that recognize envelope on the surface of infected cells. The Fc portion of these antibodies engages Fc receptors on certain innate immune cells such as natural killer (NK) cells. The engagement of activating Fc receptors on NK cells leads to secretion of granzymes and perforin, which causes the death of infected cells [20]. (c) Antibody-dependent cellular virus inhibition includes both ADCC and other Fc-mediated modes of viral inhibition. For example, Fc receptor binding to antibody attached to Env on the virion surface can mediate phagocytosis of the virus (top left of panel). Additionally, activated NK cells can secrete effector molecules, such as beta-chemokines, that interfere with viral entry of new target cells (bottom left of panel) [20]. (d) The CD8+ T-cell antiviral response is mediated by major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-1) proteins that present short processed viral peptides on the surface of HIV-infected cells. CD8+ T cells are activated upon recognition of MHC-1-peptide complexes and begin to produce granzymes and perforin that kill the infected cell. Also, other antiviral cytokines are secreted from CD8+ T cells that inhibit replication of HIV-1. Adapted from [21].

bNAbs emerge late in natural infection in 10–30% of HIV-infected individuals [24,25,26,27]. Antibody-based vaccines aim to elicit these types of bNAbs. A variety of vaccines have been utilized to elicit such responses, including nef-deleted live-attenuated viruses, virus-like particles, Env proteins and viral vectors or DNA-encoding env [28,29] (Fig. 2). Nef-deleted lentiviruses were among the first experimental vaccines to confer protection against simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus macaques [30]; however, the high mutation rate of retroviruses [28] can lead to reversion of the vaccine strain to a pathogenic virus [31]. This possibility raises a serious safety concern for this class of vaccines in humans. Virus-like lentiviral particles (VLPs) represent a safer alternative to live-attenuated virus vaccines because these particles lack a viral genome [28]. Although VLPs have proven to be immunogenic, antibody responses seem to be directed to nonfunctional Env variants on the surface of the VLP [32]. The low density of viral spike on the virus surface is suboptimal for the induction of immune responses [9]. In addition, VLPs have not proven highly effective in relevant animal models [33] and are hard to produce. Efforts to create an Env protein-based vaccine have been hampered by the inherent instability of the protein. Covalent modification, deletion of cleavage sites and the addition of trimerization motifs have improved monomeric and trimeric Env immunogens [34]. Immunization with DNA encoding HIV-1 env has been examined as another means of introducing HIV-1 Env immunogens in vivo [35,36]. Similarly, viral vectors, derived from poxviruses or adenoviruses, for example, can deliver HIV-1 env to target cells for in-vivo expression [37,38]. However, pre-existing immunity to the viral vector reduces CD8+ cell immunity and complicates the use of such viral vectors in humans [39].

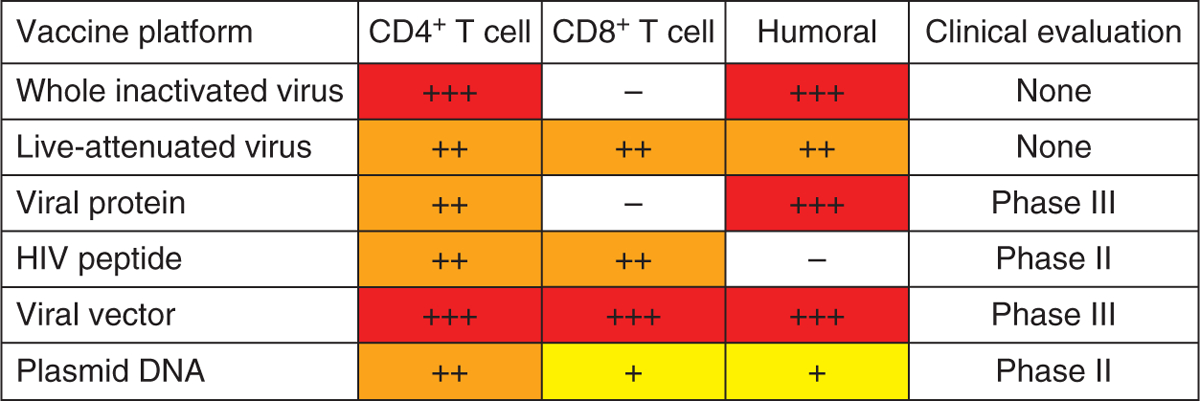

Fig. 2. The magnitude and evaluation of vaccine-elicited immune responses according to delivery platform.

The relative magnitudes of cellular and humoral immune responses elicited by different vaccine platforms are shown as high (red), medium (orange) or low (yellow). Responses not elicited by a particular vaccine platform are shown in white. The last column denotes the highest clinical trial phase for which each platform has been tested. Adapted from [29].

The rationale for T-lymphocyte-based vaccines

Cell-mediated immunity generally targets virally infected cells through the recognition of viral proteins presented on major histocompatibility complex proteins. However, HIV-1 can infect cells and enter a state of latency that allows it to evade the cellular immune response [6]. Because cell-mediated immunity does not act on the virus directly and inactivate it, it would be more likely to provide control of virus replication rather than preventing infection (Fig. 1d). However, the rapidity with which T lymphocytes respond to HIV-1 and their association with control of natural HIV-1 infection suggests that this response could help to clear virus when neutralizing antibodies are not completely effective [40–42]. Thus, the goal of a T-cell vaccine is to control viremia to background levels, likely in combination with a protective antibody response, which would together reduce the likelihood of HIV-1 transmission [43,29].

Many of the same vaccine vectors used to induce antibody responses can also elicit T-lymphocyte responses but differ with respect to immunogen inserts (Fig. 2). T-lymphocyte-based vaccines contain viral proteins from the surface and inside the virion, whereas antibody-based vaccines target Env. Each T-lymphocyte approach has the overall goal of introducing HIV-1 antigens for presentation to T cells through major histocompatibility complex class I and II molecules (Fig. 1). DNA vaccination has been one mechanism for introducing viral antigens into cells for presentation. This approach is limited by inefficient DNA uptake by antigen-presenting cells and often requires several injections. To improve the immunogenicity of DNA vaccination, new delivery methods such as DNA injection followed by electroporation are being tested [29].

Poxvirus, adenovirus and cytomegalovirus (CMV) vectors are also used to stimulate T-lymphocyte responses [44]. However, recognition of poxvirus antigens in addition to the HIV-1 immunogen complicates the use of these viral vectors [29]. Replication-incompetent adenoviruses have been employed as alternative viral vectors that express only the HIV-1 immunogen and elicit robust CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses [29]. In studies in NHP, CMV vectors elicited T-cell responses capable of controlling viremia to undetectable levels, although they were not effective in preventing infection entirely [45].

Combinatorial approaches to vaccination

Due to the lack of success of vaccines that aim to stimulate humoral or cell-mediated adaptive responses, it is generally agreed that an effective vaccine will need to elicit both neutralizing antibodies and high quality antiviral T lymphocytes [46,47]. Heterologous prime-boost – priming the immune system with one modality and boosting with a different one – may be an effective regimen for achieving this response [46]. Indeed, DNA prime and protein boost vaccination generates better antibody responses than either DNA or protein alone [28,48–50]. These same results have also been seen for DNA prime and viral vector boost [51]. Heterologous prime-boost immunization also increases the memory CD8+ T-lymphocyte pool [52]. Other strategies, for example, the use of two different viral vectors or viral vector prime and protein boost, have also been examined [37]. As discussed below, a poxvirus vector prime and protein boost has thus far provided the only evidence to date that a vaccine can prevent infection in humans [19].

HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trials

The first HIV-1 vaccine trial was conducted in 1987 [53]. There have since been more than 220 vaccine trials [54]. Of these, only four have progressed to clinical efficacy trials (phase IIb and phase III; Fig. 3) [55]. During this period, the focus of vaccine development has changed. Initial vaccine candidates addressed the hypothesis that nonneutralizing antibodies could prevent acquisition of infection and were tested in two efficacy trials, VAX003 and VAX004. Subsequently, the focus of vaccine design shifted to T-cell-based immunity, leading to the Step trial of recombinant adenoviral (rAd) vectors expressing internal viral proteins. Most recently, the RV144 trial merged T-cell and antibody-based vaccine approaches, with the first indications that a vaccine could prevent HIV infection, although with modest efficacy in humans (Fig. 3).

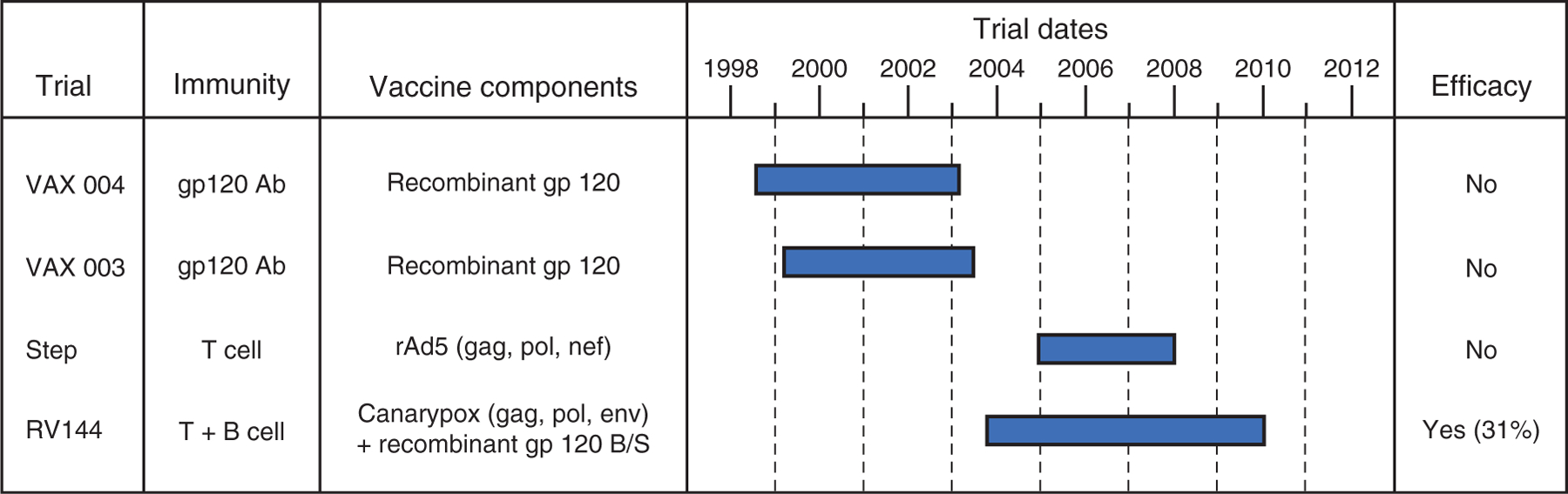

Fig. 3. Vaccine concepts, timelines and outcomes of HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trials.

To date, four vaccine efficacy trials have been performed: VAX004, VAX003, Step and RV144. The type of immunity elicited by each vaccine (antibodies and/or T cells), the vaccine components, the timeline of the trial and the resulting efficacy are shown. RV144, which elicited both cellular and humoral responses, is the first (modestly) efficacious HIV vaccine and provides a starting point for future vaccine design. Adapted from [55].

VAX003 and VAX004

VAX003 and VAX004, two phase III clinical trials, were designed to induce Env-specific antibodies by vaccination with recombinant gp120 s (rgp120). VAX004, conducted in the USA, Canada and the Netherlands, tested two clade B gp120 s (AIDSVAX B/B) in a cohort of high-risk individuals, predominantly men who have sex with men. VAX003 (AIDSVAX B/E), conducted in Thailand, contained one clade B and one clade E gp120, and enrolled a high-risk study population of injection drug users [56,57]. In total, 7949 volunteers participated in these studies. Neither vaccine reduced the number of HIV infections, delayed disease progression or lowered viral load in those who became infected [56–60]. In hindsight, the failure of the AIDSVAX immunogens is not altogether surprising. Although Env-based vaccines were known to be immunogenic and can elicit antibodies capable of neutralizing laboratory-adapted strains of HIV-1, later analyses showed that these antibodies could not neutralize most naturally circulating HIV-1 strains [61,62]. Thus, it appeared that a successful B-cell vaccine would require a qualitatively different antibody response, for example, potent and bNAbs and/or those active at mucosal sites of viral entry.

The Step study

The Step study represented a fundamental shift in vaccine strategy to a T-cell-based vaccine designed to lower viral load and slow disease progression. Preclinical data showed that NHP immunized with an Ad5 vector carrying the gag gene demonstrated more effective control of viral load after primary infection [63]. This result, combined with a general frustration at the lack of development of a B-cell-based vaccine, created enthusiasm for the Step study [64]. Volunteers, again individuals at high risk for infection, were immunized with an Ad5 replication-incompetent vector carrying gag, pol and nef genes. No Env DNA or protein was included in the vaccine, and thus no humoral immune responses were expected. Even though T-lymphocyte-based vaccines were not generally expected to impact the acquisition of infection, the two primary outcomes measured in this study were a reduction in infection and a lowered viral load set point. Although this MRKAd5 vaccine was able to generate expected T-cell responses (including HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells targeting gag, pol and nef gene products), it did not afford vaccinees’ protection against infection or attenuated viremia after infection. Furthermore, it appeared that uncircumcized men with pre-existing immunity to the Ad5 vector had increased rates of HIV acquisition [65], raising a potential safety concern, although the small numbers largely in a single risk group has left an understanding of this trend incomplete [66–68].

Analysis of the failures of the Step study has led to three important, and sobering, realizations. First, similar to the doubts that the VAX003 and VAX004 trials created about the efficacy of nonneutralizing antibodies, the failure of the MRKAd5 to impact viral load in infected vaccinees raised questions about the feasibility of T-cell-based vaccines. Second, the discordance between Ad5 in reducing viral load in the numerous NHP studies and the lack of an effect in the Step trial highlights qualifications about reliance on NHP models to predict human efficacy [63,69,70]. Third, the Step study underscored the impact of pre-existing immunity to Ad5 viral vectors. Pre-existing immunity to Ad5 can be as high as 60% in at-risk populations in the Netherlands and 90% in some demographics in sub-Saharan Africa [71]. Because other viral vectors have had varied success, efforts are still ongoing to identify novel Ad viruses with low or no pre-existing immunity in the general population [72].

RV144

Before the negative results of the VAX003 and VAX004 trials were announced, a related vaccine efficacy trial using the same Clade B and Clade E rgp120 was begun in Thailand. However, there were a number of important differences between this trial and the earlier AIDSVAX B/B and B/E trials. First, the trial vaccine schedule included a canarypox vector expressing gag, pol and env (ALVAC-HIV) as prime followed by an rgp120 (AIDSVAX B/E) protein boost. Thus, the vaccine could potentially induce both cell-mediated and humoral immunity. Notably, both components of the vaccine, the ALVAC canarypox viral vector and the AIDSVAX rgp120, failed to show any form of protective immunity in earlier clinical trials. Moreover, the study participants came from the general population in Thailand, consisting predominantly of individuals at low risk of infection, thus differing from the high-risk populations studied in the VAX003, VAX004 and Step trials.

Over 16 000 individuals were enrolled in this trial. Eight thousand one hundred and ninety seven volunteers received the vaccine, of whom 51 became infected with HIV-1 over the course of 3.5 years, compared to 74 infections of 8198 in the placebo treatment arm. Using a modified intent-to-treat statistical analysis, these results were statistically significant (P = 0.04), meaning that this study and the vaccine were the first and, to date, only (modestly) successful ones [19]. The efficacy was 31%, which is not enough for licensure, but provided the basis for further testing and optimization of this vaccine concept. No differences were observed in postinfection viral load or CD4+ T-cell counts between the treatment and placebo arms [19]. In-depth immunological analysis of biological samples from the RV144 trial is ongoing. A negative association between the presence of V1/V2-binding antibodies and the risk of infection has been identified, but the mechanisms underlying the role of V1/V2 antibodies and protection are not fully elucidated [73].

Further analysis of immune correlates is especially important, with specific emphasis on identification of neutralizing and nonneutralizing antibodies; the impacts of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cellular virus inhibition and other Fc effector functions; and antigen-specific cellular immune responses and cellular immunogenicity [64,74,75]. These associations lead into possible mechanisms of protection for this vaccine regimen and will provide a biomarker that will be evaluated in future vaccine studies.

Future challenges and opportunities

The RV144 trial showed modest efficacy and provided the first proof-of-concept for a successful HIV vaccine. However, numerous challenges and opportunities exist for the field to progress to the identification of a licensed, effective HIV vaccine. Four areas are highlighted in the following sections.

Improved animal models

NHPs infected with either SIV or SHIV are currently the best described and most widely used model of HIV infection in humans [76]. HIV-1 vaccine strategies are, therefore, often tested in nonhuman primate models prior to their translation into the clinic [77]. These NHP studies allow for the assessment of immunogenicity and protection from SIV or SHIV infection. Although SIV/SHIV infections of NHP mimic many aspects of pathogenic HIV infection in humans, discordant results between trials in NHP and humans emphasize the need to refine animal models of the human disease. Thus, the field is still looking for predictive models and immunoassays to use for HIV-1 vaccine evaluation. However, without known correlates of protection, it has been difficult to predict what type of immunity an efficacious vaccine needs to generate.

One major improvement has been in the administration of repetitive mucosal viral challenges. In contrast to the older practice of single high dose intravenous challenge, lower dose mucosal challenges (rectal, vaginal and penile) better approximate natural noninjection drug user transmission in humans [78–80].

The NHP models in general present a number of limitations, including cost, which typically limit the number of animals that can be utilized in studies. Humanized mouse models may provide an alternative model for both basic research and preclinical testing. One promising humanized mouse model is the BLT mouse, and the Veloc Immune mouse and Xeno Mouse can be used to evaluate human antibody responses [81–83]. Specifically, for the elicitation of relevant human antibody responses, these mice, genetically modified by knock-in of the human immunoglobulin G locus [81,83], can be used to better model the human antibody response and to guide selection of immunogens for further testing. Improvement and innovation of animal models will help ensure that the most promising vaccine candidates can advance expeditiously into definitive human trials.

Rational structure-based vaccine design

Identifying conserved sites of vulnerability on HIV Env can provide the starting point for a rational structure-based approach to vaccine design. bNAbs often target these sites of vulnerability (Fig. 4) [84–87]. Thus, identification of bNAbs and elucidation of the structure of these antibodies are powerful tools for immunogen design [88,89]. The following four key sites are targeted by bNAbs and provide a starting point for immunogen design: the CD4+ binding site (CD4bs), a quaternary site on the V1/V2 loops, carbohydrates on the outer domain and the membrane proximal external region (MPER). The antibody b12 targets the CD4bs and for many years was the prototype antibody for this site [90] (Fig. 4). Recently, new CD4bs antibodies, the prototype of which isVRC01, have been identified. They target the CD4bs more precisely than b12, are highly potent and can neutralize over 90% of circulating viral strains [16,86,91].

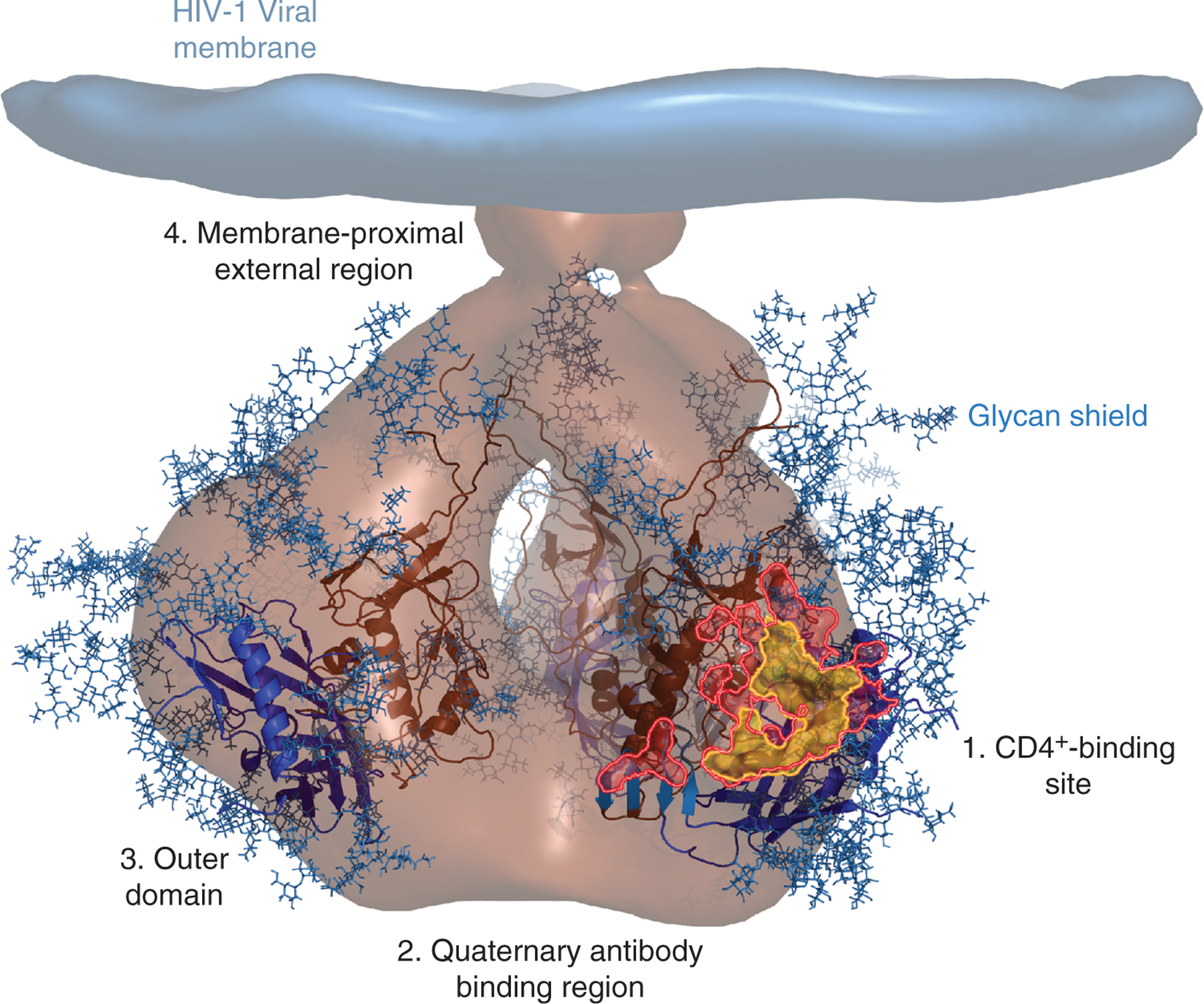

Fig. 4. Broadly neutralizing antibodies target sites of vulnerability on the HIV-1 envelope.

A cryo-electron microscopy tomogram of the HIV-1 envelope (light brown) [84] is shown docked with the crystal structures of the gp120 inner domain (dark brown ribbons) and outer domain (blue ribbons) [85]. Multiple N-linked glycans (blue sticks) cover the surface envelope, creating a glycan shield that can help HIV escape immune detection. Four sites of conserved vulnerability, each targeted by a unique class of bNAbs, are shown: 1. the CD4+ binding site, 2. the quaternary antibody binding regions, 3. the outer domain and 4. the membrane-proximal external region. VRC01, a CD4bs antibody, specifically targets the highly conserved site of initial CD4+ attachment, as shown by their overlapping footprints (VRC01, pink; site of CD4+ attachment, yellow) [86,87].

Four different types of immunogens could be used to elicit CD4bs antibodies: Env trimers, Env monomers, Env subunits such as the outer domain or Env peptides displayed on scaffolds [88]. Bioinformatics and in-silica protein design [89] can be used to make modifications to native Env that stabilize the immunogen or mask/remove undesired epitopes. The second site of vulnerability is the glycan-heavy V1/V2 region on Env. The recently described antibodies PG9 and PG16 bind to a discontinuous epitope on the V1/V2 loops and have been termed quaternary antibodies [92,93]. Membrane-bound trimers and monomers have both been used as potential immunogens, but vaccinations in humans and animal models have failed to elicit quaternary antibodies [92]. The third site of vulnerability is a high mannose region on the outer domain of Env. Until recently, 2G12 was the only known antibody to bind this site [94] and creation of 2G12 in vivo requires a variable-domain swap [95]. This finding suggests that this antibody is rare and would be hard to elicit with a vaccine. However, identification of new outer domain, glycan-binding antibodies, represented by PGT128, suggests that this site of vulnerability is more frequently targeted than previously assumed [18]. PGT128 binds two glycans, including a conserved glycan at position 332, and part of the V3 loop [17]. PGT128 and PG9/PG16 share similar binding motifs; both require an extended CDR H3 that recognizes a conserved glycan and nearby polypeptide [17,93]. Together, these glycan-dependent antibodies are the most commonly elicited bNAbs and are thus promising vaccine targets [18,93,96].

The MPER region represents a fourth site of vulnerability. At least two bNAbs recognize the MPER – 4E10 and 2F5 – and more effective antibodies are likely to be identified in future studies. The structure of these antibodies in complex with gp120 showed that hydrophobic patches on the antibodies are key for stable interactions with Env [97]. Stabilized peptides and scaffolds have been tested as immunogens [97–99], but have failed to elicit similar antibodies. The hydrophobic patches on these antibodies are difficult to maintain because they are often polyreactive, which may lead to clonal deletion [100].

One of the challenges facing structure-based design is how to elicit antibodies with the high degree of somatic mutation found in the bNAbs that guide rational design. The degree of somatic mutation is important as the germline counterparts of the bNAbs mentioned above have lower or no neutralizing potency and breadth. Thus, a successful immunogen must be able to bind the germline antibody, select for the appropriate primary recombinational events and coax the antibodies toward the appropriate mature form [88].

Passive immunization

To date, it has not been possible to elicit bNAbs like VRC01, 4E10 or PG9 by vaccination. To provide antibodies with these defined specificities to individuals at high risk of HIV-1 infection, passive immunization has been under further investigation. The basis of this strategy is the delivery of a bNAb in a way that allows for sustained expression. This end can be achieved with the antibodies themselves, engineered for high potency and long half-life to minimize the frequency of administration and maximize the duration of protection. Alternatively, it is now possible to deliver antibody molecules with gene-based vectors, for example by plasmid DNA electroporation or with replication-defective viral vectors, such as adeno-associated virus vectors. These approaches have been investigated in rodents, NHP and humanized mouse models to evaluate their expression and ability to protect against infection [101–104]. Adeno-associated virus has been able to mediate antibody expression for over a year, providing protection against SIV infection in macaques and HIV infection in humanized mice [103,104]. This approach is not without its own challenges. Pre-existing immunity to the vector and induced immunity to the delivered antibody are primary concerns [105,106]. Also, the safety of gene delivery must be ensured, particularly the ability to extinguish antibody gene expression in case of an unexpected adverse event.

Correlates of protection and innovative vaccine trial design

The identification of immune correlates of protection is a high priority for HIV-1 vaccine research. Although the NHP model has shown limitations in the past, there are still efforts to define correlates of protection from SIV infection with live-attenuated vaccines [107] and in NHP models wherein protection from acquisition has been demonstrated [38,108]. Because RV144 is the only HIV vaccine trial that has shown efficacy, it is being critically investigated to identify correlates of protection [64,109], and such positive immune responses are now being identified [73].

The need to define correlates of protection from HIV-1 infection warrants novel vaccine trial designs wherein promising vaccine candidates can be tested in populations sufficiently large to allow efficacy to be determined. Furthermore, the trial designs should allow for modification of the trial due to the data being obtained [55]. The latter means that the clinical data derived from vaccine trials would need to be assessed more quickly than traditionally done, so that the necessary changes can be made [55]. The study population has to be carefully considered, as the incidence rate should be such that the vaccine would have a chance to show protection against infection. Then subsequent trials could be conducted in the same population [55]. Individuals from various risk levels should be included in a study population of sufficient size to determine even modest differences in virus acquisition.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ati Tislerics for assistance with manuscript preparation and Brenda Hartman, Jonathan Stuckey and Julie Farrar for figure preparation.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Vaccine Research Center, NIAID, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science 2010; 329:1168–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet 2010; 375:2092–2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2587–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munier CM, Andersen CR, Kelleher AD. HIV vaccines: progress to date. Drugs 2011; 71:387–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lassen K, Han Y, Zhou Y, Siliciano J, Siliciano RF. The multifactorial nature of HIV-1 latency. Trends Mol Med 2004; 10:525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korber B, Muldoon M, Theiler J, Gao F, Gupta R, Lapedes A, et al. Timing the ancestor of the HIV-1 pandemic strains. Science 2000; 288:1789–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore PL, Crooks ET, Porter L, Zhu P, Cayanan CS, Grise H, et al. Nature of nonfunctional envelope proteins on the surface of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 2006; 80:2515–2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein JS, Gnanapragasam PN, Galimidi RP, Foglesong CP, West AP Jr, Bjorkman PJ. Examination of the contributions of size and avidity to the neutralization mechanisms of the anti-HIV antibodies b12 and 4E10. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:7385–7390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwong PD, Doyle ML, Casper DJ, Cicala C, Leavitt SA, Majeed S, et al. HIV-1 evades antibody-mediated neutralization through conformational masking of receptor-binding sites. Nature 2002; 420:678–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyatt R, Kwong PD, Desjardins E, Sweet RW, Robinson J, Hendrickson WA, et al. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature 1998; 393:705–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston MI, Fauci AS. HIV vaccine development: improving on natural immunity. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:873–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stranford SA, Skurnick J, Louria D, Osmond D, Chang SY, Sninsky J, et al. Lack of infection in HIV-exposed individuals is associated with a strong CD8(+) cell noncytotoxic anti-HIV response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96:1030–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freel SA, Lamoreaux L, Chattopadhyay PK, Saunders K, Zarkowsky D, Overman RG, et al. Phenotypic and functional profile of HIV-inhibitory CD8 T cells elicited by natural infection and heterologous prime/boost vaccination. J Virol 2010; 84:4998–5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spentzou A, Bergin P, Gill D, Cheeseman H, Ashraf A, Kaltsidis H, et al. Viral inhibition assay: a CD8 T cell neutralization assay for use in clinical trials of HIV-1 vaccine candidates. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu X, Yang ZY, Li Y, Hogerkorp CM, Schief WR, Seaman MS, et al. Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science 2010; 329:856–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pejchal R, Doores KJ,Walker LM, Khayat R, Huang PS,Wang SK, et al. A potent and broad neutralizing antibody recognizes and penetrates the HIV glycan shield. Science 2011; 334:1097–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, Falkowska E, Pejchal R, Julien JP, et al. Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature 2011; 477:466–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Chiu J, Paris R, et al. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:2209–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forthal DN, Moog C. Fc receptor-mediated antiviral antibodies. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2009; 4:388–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overbaugh J, Morris L. The antibody response against HIV-1. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2:a007039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mascola JR, Lewis MG, Stiegler G, Harris D, VanCott TC, Hayes D, et al. Protection of Macaques against pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus 89.6PD by passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 1999; 73:4009–4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hessell AJ, Poignard P, Hunter M, Hangartner L, Tehrani DM, Bleeker WK, et al. Effective, low-titer antibody protection against low-dose repeated mucosal SHIV challenge in macaques. Nat Med 2009; 15:951–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhillon AK, Donners H, Pantophlet R, Johnson WE, Decker JM, Shaw GM, et al. Dissecting the neutralizing antibody specificities of broadly neutralizing sera from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected donors. J Virol 2007; 81:6548–6562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Migueles SA, Welcher B, Svehla K, Phogat A, Louder MK, et al. Broad HIV-1 neutralization mediated by CD4-binding site antibodies. Nat Med 2007; 13:1032–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doria-Rose NA, Klein RM, Manion MM, O’Dell S, Phogat A, Chakrabarti B, et al. Frequency and phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus envelope-specific B cells from patients with broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 2009; 83:188–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sather DN, Armann J, Ching LK, Mavrantoni A, Sellhorn G, Caldwell Z, et al. Factors associated with the development of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol 2009; 83:757–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker LM, Burton DR. Rational antibody-based HIV-1 vaccine design: current approaches and future directions. Curr Opin Immunol 2010; 22:358–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koup RA, Douek DC. Vaccine design for CD8 T lymphocyte responses. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2011; 1:a007252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daniel MD, Kirchhoff F, Czajak SC, Sehgal PK, Desrosiers RC. Protective effects of a live attenuated SIV vaccine with a deletion in the nef gene. Science 1992; 258:1938–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawai ET, Hamza MS, Ye M, Shaw KE, Luciw PA. Pathogenic conversion of live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccines is associated with expression of truncated Nef. J Virol 2000; 74:2038–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crooks ET, Moore PL, Franti M, Cayanan CS, Zhu P, Jiang P, et al. A comparative immunogenicity study of HIV-1 virus-like particles bearing various forms of envelope proteins, particles bearing no envelope and soluble monomeric gp120. Virology 2007; 366:245–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Persson RH, Cao SX, Cates G, Yao FL, Klein MH, Rovinski B. Modifications of HIV-1 retrovirus-like particles to enhance safety and immunogenicity. Biologicals 1998; 26:255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phogat S, Wyatt R. Rational modifications of HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins for immunogen design. Curr Pharm Des 2007; 13:213–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barouch DH, Letvin NL. DNA vaccination for HIV-1 and SIV. Intervirology 2000; 43:282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graham BS, Koup RA, Roederer M, Bailer RT, Enama ME, Moodie Z, et al. Phase 1 safety and immunogenicity evaluation of a multiclade HIV-1 DNA candidate vaccine. J Infect Dis 2006; 194:1650–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paris RM, Kim JH, Robb ML, Michael NL. Prime-boost immunization with poxvirus or adenovirus vectors as a strategy to develop a protective vaccine for HIV-1. Expert Rev Vaccines 2010; 9:1055–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barouch DH, Liu J, Li H, Maxfield LF, Abbink P, Lynch DM, et al. Vaccine protection against acquisition of neutralization-resistant SIV challenges in rhesus monkeys. Nature 2012; 482:89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casimiro DR, Chen L, Fu TM, Evans RK, Caulfield MJ, Davies ME, et al. Comparative immunogenicity in rhesus monkeys of DNA plasmid, recombinant vaccinia virus, and replication-defective adenovirus vectors expressing a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene. J Virol 2003; 77:6305–6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goonetilleke N, Liu MK, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Ferrari G, Giorgi E, Ganusov VV, et al. The first T cell response to transmitted/founder virus contributes to the control of acute viremia in HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med 2009; 206:1253–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blankson JN. Control of HIV-1 replication in elite suppressors. Discov Med 2010; 9:261–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMichael AJ, Borrow P, Tomaras GD, Goonetilleke N, Haynes BF. The immune response during acute HIV-1 infection: clues for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10:11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta SB, Jacobson LP, Margolick JB, Rinaldo CR, Phair JP, Jamieson BD, et al. Estimating the benefit of an HIV-1 vaccine that reduces viral load set point. J Infect Dis 2007; 195:546–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pantaleo G, Esteban M, Jacobs B, Tartaglia J. Poxvirus vector-based HIV vaccines. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010; 5:391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hansen SG, Ford JC, Lewis MS, Ventura AB, Hughes CM, Coyne-Johnson L, et al. Profound early control of highly pathogenic SIV by an effector memory T-cell vaccine. Nature 2011; 473:523–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benmira S, Bhattacharya V, Schmid ML. An effective HIV vaccine: a combination of humoral and cellular immunity? Curr HIV Res 2010; 8:441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walker BD, Ahmed R, Plotkin S. Moving ahead an HIV vaccine: use both arms to beat HIV. Nat Med 2011; 17:1194–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu SL, Abrams K, Barber GN, Moran P, Zarling JM, Langlois AJ, et al. Protection of macaques against SIV infection by subunit vaccines of SIV envelope glycoprotein gp160. Science 1992; 255:456–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang S, Kennedy JS, West K, Montefiori DC, Coley S, Lawrence J, et al. Cross-subtype antibody and cellular immune responses induced by a polyvalent DNA prime-protein boost HIV-1 vaccine in healthy human volunteers. Vaccine 2008; 26:3947–3957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomaras GD, Haynes BF. Strategies for eliciting HIV-1 inhibitory antibodies. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010; 5:421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mascola JR, Sambor A, Beaudry K, Santra S, Welcher B, Louder MK, et al. Neutralizing antibodies elicited by immunization of monkeys with DNA plasmids and recombinant adenoviral vectors expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proteins. J Virol 2005; 79:771–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Butler NS, Nolz JC, Harty JT. Immunologic considerations for generating memory CD8 T cells through vaccination. Cell Microbiol 2011; 13:925–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zagury D, Leonard R, Fouchard M, Reveil B, Bernard J, Ittele D, et al. Immunization against AIDS in humans. Nature 1987; 326:249–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.International AIDS Vaccine Initiative. Database of AIDS Vaccine Candidates in Clinical Trials. http://www.iavireport.org/trials-db/Pages/default.aspx. [Accessed 12 February 2012].

- 55.Corey L, Nabel GJ, Dieffenbach C, Gilbert P, Haynes BF, Johnston M, et al. HIV-1 vaccines and adaptive trial designs. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3:79s13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harro CD, Judson FN, Gorse GJ, Mayer KH, Kostman JR, Brown SJ, et al. Recruitment and baseline epidemiologic profile of participants in the first phase 3 HIV vaccine efficacy trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004; 37:1385–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pitisuttithum P, Gilbert P, Gurwith M, Heyward W, Martin M, van Griensven F, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy trial of a bivalent recombinant glycoprotein 120 HIV-1 vaccine among injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. J Infect Dis 2006; 194:1661–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flynn NM, Forthal DN, Harro CD, Judson FN, Mayer KH, Para MF. Placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of a recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine to prevent HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 2005; 191:654–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilbert PB, Ackers ML, Berman PW, Francis DP, Popovic V, Hu DJ, et al. HIV-1 virologic and immunologic progression and initiation of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1-infected subjects in a trial of the efficacy of recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:974–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pitisuttithum P. HIV vaccine research in Thailand: lessons learned. Expert Rev Vaccines 2008; 7:311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wrin T, Nunberg JH. HIV-1MN recombinant gp120 vaccine serum, which fails to neutralize primary isolates of HIV-1, does not antagonize neutralization by antibodies from infected individuals. AIDS 1994; 8:1622–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mascola JR, Snyder SW, Weislow OS, Belay SM, Belshe RB, Schwartz DH, et al. Immunization with envelope subunit vaccine products elicits neutralizing antibodies against laboratory-adapted but not primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Vaccine Evaluation Group. J Infect Dis 1996; 173:340–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shiver JW, Fu TM, Chen L, Casimiro DR, Davies ME, Evans RK, et al. Replication-incompetent adenoviral vaccine vector elicits effective antiimmunodeficiency-virus immunity. Nature 2002; 415:331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Connell RJ, Kim JH, Corey L, Michael NL. Human immunodeficiency virus vaccine trials In: Bushman FD, Nabel GJ, Swanstrom R, editors. HIV: From biology to prevention and treatment. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2011. pp. 483–504. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, Fitzgerald DW, Mogg R, Li D, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet 2008; 372:1881–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hutnick NA, Carnathan DG, Dubey SA, Makedonas G, Cox KS, Kierstead L, et al. Baseline Ad5 serostatus does not predict Ad5 HIV vaccine-induced expansion of adenovirus-specific CD4R T cells. Nat Med 2009; 15:876–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Brien KL, Liu J, King SL, Sun YH, Schmitz JE, Lifton MA, et al. Adenovirus-specific immunity after immunization with an Ad5 HIV-1 vaccine candidate in humans. Nat Med 2009; 15:873–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.D’Souza MP, Frahm N. Adenovirus 5 serotype vector-specific immunity and HIV-1 infection: a tale of T cells and antibodies. AIDS 2010; 24:803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Casimiro DR, Wang F, Schleif WA, Liang X, Zhang ZQ, Tobery TW, et al. Attenuation of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 infection by prophylactic immunization with dna and recombinant adenoviral vaccine vectors expressing Gag. J Virol 2005; 79:15547–15555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wilson NA, Reed J, Napoe GS, Piaskowski S, Szymanski A, Furlott J, et al. Vaccine-induced cellular immune responses reduce plasma viral concentrations after repeated low-dose challenge with pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239. J Virol 2006; 80:5875–5885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kostense S, Koudstaal W, Sprangers M, Weverling GJ, Penders G, Helmus N, et al. Adenovirus types 5 and 35 seroprevalence in AIDS risk groups supports type 35 as a vaccine vector. AIDS 2004; 18:1213–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barouch DH. Novel adenovirus vector-based vaccines for HIV-1. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010; 5:386–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomaras GD, Alam SM, et al. Immune correlates analysis of the ALVAC-AIDSVAX HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1275–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim JH, Rerks-Ngarm S, Excler JL, Michael NL. HIV vaccines: lessons learned and the way forward. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010; 5:428–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koup RA, Graham BS, Douek DC. The quest for a T cell-based immune correlate of protection against HIV: a story of trials and errors. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lifson JF, Haigwood NL. Lessons in nonhuman primate models from AIDS vaccine research: from minefields to milestones In: Bushman FD, Nabel GJ, Swanstrom R, editors. HIV: From Biology to Prevention and Treatment. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2011. pp. 463–482. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haigwood NL. Predictive value of primate models for AIDS. AIDS Rev 2004; 6:187–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Keele BF, Li H, Learn GH, Hraber P, Giorgi EE, Grayson T, et al. Low-dose rectal inoculation of rhesus macaques by SIVsmE660 or SIVmac251 recapitulates human mucosal infection by HIV-1. J Exp Med 2009; 206:1117–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stone M, Keele BF, Ma ZM, Bailes E, Dutra J, Hahn BH, et al. A limited number of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) env variants are transmitted to rhesus macaques vaginally inoculated with SIVmac251. J Virol 2010; 84:7083–7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ma ZM, Keele BF, Qureshi H, Stone M, Desilva V, Fritts L, et al. SIVmac251 is inefficiently transmitted to rhesus macaques by penile inoculation with a single SIVenv variant found in rampup phase plasma. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2011; 27:1259–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jakobovits A, Amado RG, Yang X, Roskos L, Schwab G. From XenoMouse technology to panitumumab, the first fully human antibody product from transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol 2007; 25:1134–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wege AK, Melkus MW, Denton PW, Estes JD, Garcia JV. Functional and phenotypic characterization of the humanized BLT mouse model. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2008; 324:149–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tkaczyk C, Hua L, Varkey R, Shi Y, Dettinger L, Woods R, et al. Identification of antialpha toxin mAbs that reduce severity of Staphylococcus aureus dermonecrosis and exhibit a correlation between affinity and potency. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012; 19:377–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu J, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, Sapiro G, Subramaniam S. Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature 2008; 455:109–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pancera M, Majeed S, Ban YE, Chen L, Huang CC, Kong L, et al. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 with gp41-interactive region reveals layered envelope architecture and basis of conformational mobility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:1166–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhou T, Georgiev I, Wu X, Yang ZY, Dai K, Finzi A, et al. Structural basis for broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by antibody VRC01. Science 2010; 329:811–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhou T, Xu L, Dey B, Hessell AJ, Van Ryk D, Xiang SH, et al. Structural definition of a conserved neutralization epitope on HIV-1 gp120. Nature 2007; 445:732–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ. Rational design of vaccines to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2011; 1:a007278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nabel GJ, Kwong PD, Mascola JR. Progress in the rational design of an AIDS vaccine. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2011; 366:2759–2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Burton DR, Desrosiers RC, Doms RW, Koff WC, Kwong PD, Moore JP, et al. HIV vaccine design and the neutralizing antibody problem. Nat Immunol 2004; 5:233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Ueberheide B, Diskin R, Klein F, Oliveira TY, et al. Sequence and structural convergence of broad and potent HIV antibodies that mimic CD4 binding. Science 2011; 333:1633–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, et al. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science 2009; 326:285–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McLellan JS, Pancera M, Carrico C, Gorman J, Julien JP, Khayat R, et al. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Nature 2011; 480:336–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sanders RW, Venturi M, Schiffner L, Kalyanaraman R, Katinger H, Lloyd KO, et al. The mannose-dependent epitope for neutralizing antibody 2G12 on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp120. J Virol 2002; 76:7293–7305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Calarese DA, Scanlan CN, Zwick MB, Deechongkit S, Mimura Y, Kunert R, et al. Antibody domain exchange is an immunological solution to carbohydrate cluster recognition. Science 2003; 300:2065–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gray ES, Madiga MC, Hermanus T, Moore PL, Wibmer CK, Tumba NL, et al. The neutralization breadth of HIV-1 develops incrementally over four years and is associated with CD4R T cell decline and high viral load during acute infection. J Virol 2011; 85:4828–4840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ofek G, Tang M, Sambor A, Katinger H, Mascola JR, Wyatt R, et al. Structure and mechanistic analysis of the antihuman immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2F5 in complex with its gp41 epitope. J Virol 2004; 78:10724–10737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ofek G, Guenaga FJ, Schief WR, Skinner J, Baker D, Wyatt R, et al. Elicitation of structure-specific antibodies by epitope scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:17880–17887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ofek G, McKee K, Yang Y, Yang ZY, Skinner J, Guenaga FJ, et al. Relationship between antibody 2F5 neutralization of HIV-1 and hydrophobicity of its heavy chain third complementarity-determining region. J Virol 2010; 84:2955–2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Haynes BF, Fleming J, St Clair EW, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Kunert R, et al. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science 2005; 308:1906–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lewis AD, Chen R, Montefiori DC, Johnson PR, Clark KR. Generation of neutralizing activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in serum by antibody gene transfer. J Virol 2002; 76:8769–8775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fang J, Qian JJ, Yi S, Harding TC, Tu GH, VanRoey M, et al. Stable antibody expression at therapeutic levels using the 2A peptide. Nat Biotechnol 2005; 23:584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Johnson PR, Schnepp BC, Zhang J, Connell MJ, Greene SM, Yuste E, et al. Vector-mediated gene transfer engenders long-lived neutralizing activity and protection against SIV infection in monkeys. Nat Med 2009; 15:901–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Balazs AB, Chen J, Hong CM, Rao DS, Yang L, Baltimore D. Antibody-based protection against HIV infection by vectored immunoprophylaxis. Nature 2012; 481:81–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chirmule N, Propert K, Magosin S, Qian Y, Qian R, Wilson J. Immune responses to adenovirus and adeno-associated virus in humans. Gene Ther 1999; 6:1574–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Calcedo R, Vandenberghe LH, Gao G, Lin J, Wilson JM. Worldwide epidemiology of neutralizing antibodies to adeno-associated viruses. J Infect Dis 2009; 199:381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Koff WC, Johnson PR, Watkins DI, Burton DR, Lifson JD, Hasenkrug KJ, et al. HIV vaccine design: insights from live attenuated SIV vaccines. Nat Immunol 2006; 7:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Letvin NL, Rao SS, Montefiori DC, Seaman MS, Sun Y, Lim SY, et al. Immune and genetic correlates of vaccine protection against mucosal infection by SIV in monkeys. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3:81ra36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Haynes BF, Liao HX, Tomaras GD. Is developing an HIV-1 vaccine possible? Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010; 5:362–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]