Abstract

COVID-19 transmission in London city was discussed in this work from an urban context. The association between COVID-19 cases and climate indicators in London, UK were analysed statistically employing published data from national health services, UK and Time and Date AS based weather data. The climatic indicators included in the study were the daily averages of maximum and minimum temperatures, humidity, and wind speed. Pearson, Kendall, and Spearman rank correlation tests were selected for data analysis. The data was considered up to two different dates to study the climatic effect (10th May in the first study and then updated up to 16th of July in the next study when the rest of the data was available). The results were contradictory in the two studies and it can be concluded that climatic parameters cannot solely determine the changes in the number of cases in the pandemic. Distance from London to four other cities (Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester, and Sheffield) showed that as the distance from the epicentre of the UK (London) increases, the number of COVID-19 cases decrease. What should be the necessary measure to be taken to control the transmission in cities have been discussed.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Humidity, London, Temperature, Urban context, Transmission, Lock down, City, Transport

Highlights

-

•

This study presents an investigation of the COVID-19 transmission from the urban context.

-

•

Climatic data (temperature and humidity) is not a strong parameter to understand the transmission of COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

Distance from London to other cities was negatively associated with COVID-19 cases.

1. Introduction

Corona virus disease (CO-Corona; VI-Virus; D-Disease; 19: year) was first testified in 2019, Wuhan, Hubei province, China due to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) named the virus as SARS-CoV-2. They both share 79% of sequential identity (Kong et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). The first case was reported due to the zoonotic transmission from a live wild animal trade market (Tay, Poh, Rénia, MacAry, & Ng, 2020; Huang et al., 2020). The first patient was hospitalized on 12th Dec 2019 while 80 deaths were reported by 26th January 2020 (Zhou et al., 2020). Cough, fever, fatigue, headache and myalgias, shortness of breath, and sputum production, are the symptoms of the COVID-19 infection (Chen, Liang, et al., 2020; Chen, Zhou, et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). COVID-19 is primarily transmitted from symptomatic people to others who are in close proximity through respiratory droplets (sneeze, cough, secretions of infected people) or by contact with contaminated objects or surfaces. However, evidence from different cases revealed that asymptomatic transmission was also dominant (Hu et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). In general, asymptomatic infections cannot be recognized until Real-Time-Polymerase Chain Reaction Test (RT-PCR) or other laboratory testing is being carried out, and symptomatic cases may not be detected if they do not seek medical attention (Nishiura & Kobayashi, 2020). Previously in 2002–03 because of SARS, more than 8000 people were infected and 774 died. In 2012, for MERS-CoV, 2494 persons were diseased and over 858 people lost their lives worldwide. COVID-19 outbreak is the sixth public health emergency of international concern following H1N1 (2009), polio (2014), Ebola (2014 in West Africa), Zika (2016), and Ebola (2019 in the Democratic Republic of Congo) (Chakraborty & Maity, 2020). On March 11, 2020, WHO announced COVID-19 as a pandemic due to 118,319 confirmed cases in a day including 4292 deaths.

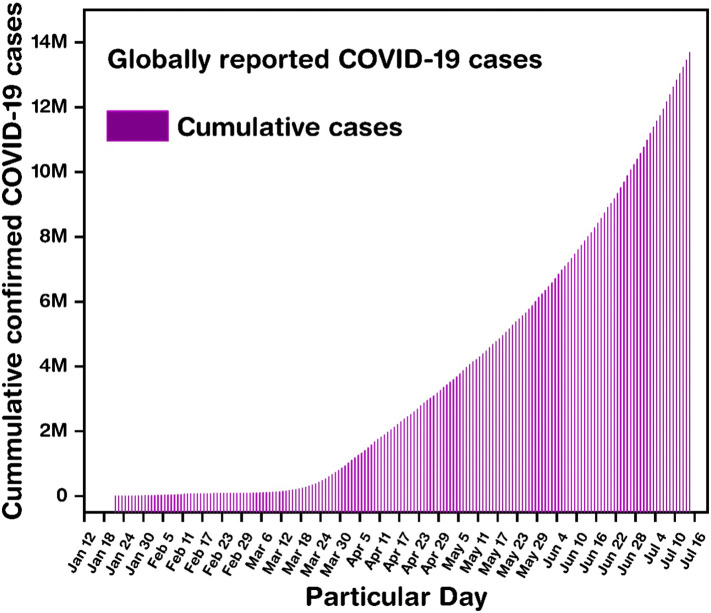

As per BBC reports, by 16th April, the total infected number raised to 2,063,161 infesting 185 countries/regions, which further elevated to 4,399,070 by 13th May (BBC, 2020e). Within two additional days, by 15th May 2020, 4,533,255 people were diseased by this virus globally causing the total decease count to be ~303,388 contaminating more than 188 countries. As of 16th of July, total cases globally reached 13,950,629, and death count is 597,601 and 213 countries and territories are affected (shown in Fig. 1 ). However, the locked-down and social distancing strategy was employed in various countries to limit the spread of COVID-19. First lockdown occurred in Whuan (Kupferschmidt & Cohen, 2020). Within three months (Jan to April 2020) the virus has spread globally and the rate of spread was high due to higher mobility of people globally via air flight (Lau et al., 2020; Nakamura & Managi, 2020). Hence, it is considered that the transmission rate through people to people transmission is very high. New terms are now prevalent to hear such as “community spreading”, “social distancing (physical distancing)”, “self-isolation”, “14 days quarantine”, “lockdown,” “break the chain” etc. All these are employed to stop spreading the virus by creating social awareness (Shaw, Kim, & Hua, 2020). WHO recently acknowledged the possibility of transmission of COVID-19 by aerosol.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative total COVID-19 casses globally as of 16th of July 2020.

United Kingdom's (UK) first COVID-19 case was reported on 31st Jan 2020 (Moss, Barlow, Easom, Lillie, & Samson, 2020; Lillie et al., 2020). Succeeding the advice from the Department of Health, the UK government requested all individuals to undergo self-isolation or home-quarantine (14–20 days) provided they visited the infected countries/regions namely, Hubei province (mainland China), Thailand, Japan, Republic of Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, and Macau (Sohrabi et al., 2020). To further prevent transmission, the UK government requested quarantined individuals not to go to GP surgeries, community dispensaries, or infirmaries (symptoms observed: unceasing cough, body temperature ≥ 37.8 °C, or flu-like complaint) but to call NHS 111 if the situation becomes worse. Unnecessary travel to Mainland China and particularly to the Hubei Province were also advised not to perform (Sohrabi et al., 2020). In the beginning, the UK's approach was more towards social distancing and suggested people over 70 to stay at home (self-isolation) (Mahase, 2020; Pollock, Roderick, Cheng, & Pankhania, 2020). This attitude changed when researcher from MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis at Imperial College London lead by Neil Ferguson indicated using a theoretical study that home isolation and the social distance still can result in a death count of ~260,000 (Ferguson et al., 2020).

As per the report, on March 10, the number of deaths related to the coronavirus was ~6. On 5th May death toll in the UK from COVID-19 was 32,313 (including suspect) which was highest in Europe as it exceeded the death toll of 29,029 (excluding suspect) in Italy (The Guardian, 2020). This number drastically increased as 95,000 people entered the UK from overseas on 13th May, since coronavirus lockdown was imposed, (Guardian, 2020). Prime minister addressed the nation advising to maintain social distance and work from home (since 16th March) and steps to be taken while under lockdown (23rd march) (Khan & Cheng, 2020). Additionally, experts also advised maintaining 2 m (or 6Ft.) distance from another person under any circumstances. As of now a reduction in socializing proved to be the most appropriate method to diminish the transmission of COVID-19 (Zhang et al., 2020). In England, from 13th of May, people were allowed to exercise more than once a day in outdoor spaces (parks), and interact with others by maintaining social distance. From 1st of June, schools for reception, year one and year six pupils were reopened while non essential retailers had permission to open their store from 5th of June in England. From 23rd June, 2 m restriction was lifted and changed to 1 m plus to enable people to meet their family and friends, help businesses get back on their feet and get people back in their jobs. From Saturday 4th of July, pubs, restaurants and hairdressers were allowed to reopen, providing they adhere to COVID-19 secure guidelines (Office, 2020). The UK government has also devoted £20,000,000 as assistance to develop a COVID-19 vaccine (BBC, 2020c). London was reported to be the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK (London Loves Business, 2020). Fig. 2 indicates the COVID-19 spread in the UK.

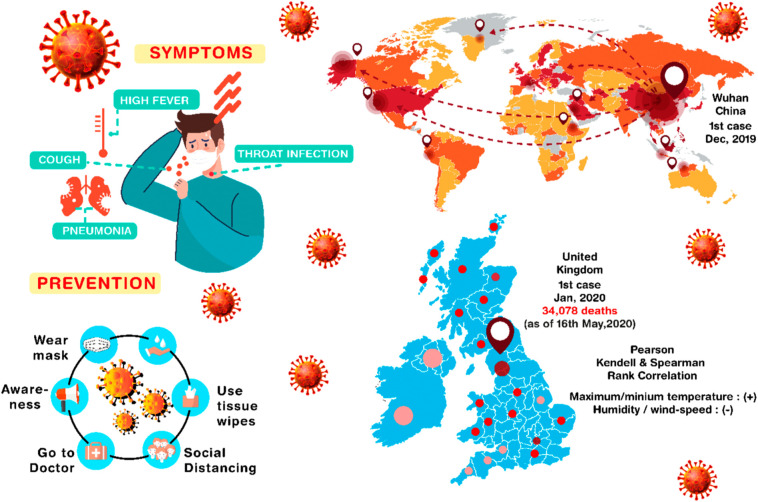

Fig. 2.

World-wide distribution of COVID-19 with symptoms and precautions to be taken against coronavirus infection and temperature, humidity, and wind speed correlation with COVID-19 epidemic in the UK.

Reason for transmission of COVID-19 is not yet clearly understood. Several researchers investigated to understand how temperature (Wu et al., 2020), humidity, air pollution (Contini & Costabile, 2020), wind, people to people had an influence on COVID-19 transmission. Transmission of COVID-19 due to temperature and humidity is a pertinent question (O'Reilly et al., 2020). Previously it was reported that the temperature range between 5 and 11 °C community outbreak occurs (Sajadi, Habibzadeh, Vintzileos, Miralles-wilhelm, & Amoroso, 2020). Another study reported that high temperature and humidity can decrease SARS-CoV-2 transmission (Wang, Tang, Feng, & Lv, 2020). Araujo & Naimi, 2020 predicted that warm and cold climates are suitable for this virus spread while arid and tropical climates are not (Araujo & Naimi, 2020). In Oslo climate, maximum and normal temperature were positively and precipitation was negatively associated with COVID-19 (Menebo, 2020). Collected data of daily confirmed cases from the capital of 27 states in Brazil also confirmed that no COVID-19 declined curve due to temperature above 25.8 °C (Prata, Rodrigues, & Bermejo, 2020). (Xie & Zhu, 2020) investigated 122 cities in China and reported that temperature has a positive linear relationship with the number of COVID-19 cases but no evidence was found which can support that COVID-19 cases counts could decline due to warm weather. Also, Yao et al. (2020) announced that temperature and UV radiation had no strong association with COVID-19 cases in Chinese cities (Yao et al., 2020).

Study related to urban perspective and COVID-19 transmission is rare. To predict the accurate impact of COVID-19, urban perspective should not be ignored as cities are the place where the transmission started. Highly populated cities and public transport of cities play an influential factor for this virus transmission. Hence ignoring urban context may not be rational. In 2018, 55% of the world's population (4·2 billion people) resided in urban areas, which is expected to be 68% by 2050. Infectious disease either originate or propagate rapidly in the cities because of the urbanization (V. J. Lee et al., 2020). Human health issues related to the urban context was previously investigated (Orimoloye, Mazinyo, Kalumba, Ekundayo, & Nel, 2019; Wang, 2020) and other work showed that property price reduced after pandemic (Ambrus, Field, & Gonzalez, 2020). The change of residential-built environment characteristics due to pandemic were also discussed (Spencer, Finucane, Fox, Saksena, & Sultana, 2020). Effect of social isolation for flu infection was also discussed before (Aiello et al., 2016). How metropolitan area can be affected from flu pandemic due to the biological, physiological, and geography, economic, and social reason was revealed by (B. Y. Lee, Bedford, Roberts, & Carley, 2008). Recently (Liu, 2020) has discussed the COVID-19 in the urban context considering the Wuhan city in China from where the pandemic started.

In this work, we tried to investigate how COVID-19 pandemic proliferated in London and four other UK cities (Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield), giving the priority for the urban context. In a city, the climate is a crucial indicator, hence, climatic data, particularly ambient parameters such as maximum temperature, minimum temperature, wind speed, and humidity were selected to realize the impact on the transmission of COVID-19 in London. Also, how the distance from London to Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield, had an impact of COVID-19 transmission have been discussed. Emphasis is given more on the urban context and possible policy with respect to the urban city has been mentioned.

2. Research methodology

2.1. Study area

London (51.50642° N, −0.12721° E) is the capital of England and one of the largest cities in the United Kingdom. The latest estimated London population is 9,304,016. The City of London is 1.12 mile2 (2.9 km2) while the Greater London area counts 606 mile2 (1569 km2) (Population, 2020). Other investigated cities are Birmingham (52.48° N, −1.90° W), Leeds (53.8° N, −1.54° E), Manchester (53.48° N, −2.24° E) and Sheffield (53.38° N, −1.48° W).

2.2. Data collection

New death dataset for COVID-19 is acquired for March 13, 2020 – July 16, 2020, from COVID-19 data archive from the National health service (NHS, 2020) and data concerning daily average climatic indicators which included maximum temperature, minimum temperature, humidity, wind-speed was attained from (AS et al., 2020). Cumulative cases and new cases data for London and other cities till 28th April was collected from the NHS England. After 29th April, data were collected from multiple sources and calculated by Public Health England (Gov.UK, 2020a). All the data were updated at 2 pm every day while confirmed death cases were included from the reported data from the previous day at 4 pm. Hence there is a lag between the date of actual cases and date of reporting. Also, this data includes only the report case from hospital (NHS, 2020). Population density for four other cities are 1438 (Leeds-314.7 Km away from London), 4264 (Birmingham 205.3 Km away from London), 4781 (Manchester, 336.1 Km away from London), 1590 (Sheffield; 259.1 Km away from London) (For National Statistics, 2020).

2.3. Data analysis

Climate dependency with COVID-19 cases was evaluated using Pearson (linear relation; shown in Eq. (1)), Kendall (shown in Eq. (2)), and Spearman rank correlation (that access how two variables are monotonically related, shown in Eq. (3)) tests to examine the correlation between variables.

Pearson correlation coefficient

| (1) |

Spearmean correlation coefficient

| (2) |

Kendall

| (3) |

Mixed-effects model (shown in Eq. (4) which include both random and fixed effects) was employed to understand how COVID-19 case in Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield, varied due to distances from London. We consider the time points from 15th March 2020 to 30th June 2020 (108 days). We have a Panel data here which is cross-sectional time-series data.

| (4) |

where, Yit represents the daily lab confirmed cases for city i (1 to 4) at time t (1 to 108); timeit represents the time at which we calculate daily lab confirmed cases for city i, distancei represents the distance from London for city i, populationi represents the population density of city i, eit ~ N(0,σe 2). We assume that the residuals are independent and identically distributed, conditional on the random effects.

The distribution of the vector of the three random effects associated with city i is assumed to be multivariate Normal: ui = (u0i, u1i, u2i)t ~ Normal(0,D), where D is the variance-covariance matrix of the random effects. b0, b1, b2, b3, b4 and b5 are fixed effects parameters and u0,u1 and u2 are random effects parameters.

The parameters b0 through b5 represent the fixed effects associated with the intercept, the covariates, and the interaction terms in the model. The fixed intercept b0 corresponds to the daily lab confirmed cases when all covariates are equal to 0, the intercept can be interpreted as the mean predicted daily lab confirmed cases for cities at time 0 (here time 0 means 15th March 2020). The parameters b1 and b2 represent the fixed effects of time and time square. The parameters b3 and b4 represent the change in daily lab confirmed cases for a unit change in distance (in km) and for a unit change in population per square kilometre respectively. The parameter b5 can be interpreted as the interaction effect between distance and population per square kilometre. Here variable time2 is included because a quadratic relationship can be seen between time and the dependent variable daily lab confirmed cases.

Here the city is a random factor in the model and for those cities, an intercept and a slope over time are the two random effects. Time is considered in both fixed and random effects. The random slope for a time at the city level indicates that the slope across time varies across cities. In other words, the effect of time on daily corona virus cases (the slope) is different for different values of cities. As this slope is a random effect, this interaction was not measured through a regression coefficient which is suitable for fixed cases. Instead, measurement focused on how much each city's slope differs from the average slope, then the variance was found for these different measures. Hence, the variance estimates the random slope. If that variance comes out to 0, it indicates that the slope of time on COVID-19 cases is similar for all cities and they don't vary from each other. u0 is individual city-specific effect and u1 is a time-specific effect and u2 is the random effect associated with the quadratic effect of time for a city.

3. Result

3.1. Climate dependency

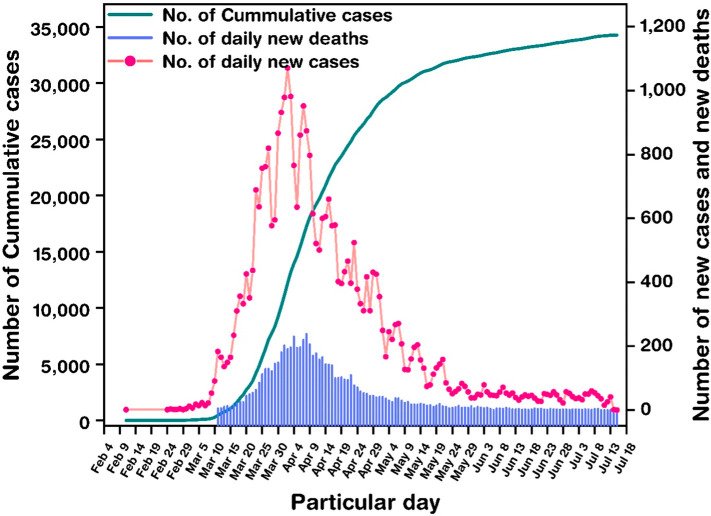

Fig. 3 observes a sharp increase, both in daily new cases and total confirmed cases for London dated March 11, 2020, onwards. The total confirmed case as of 11th March was reported ~104 which increased to 1221 by 19th March. New 13 cases were observed on 11th March, which drastically increased to 1220 by 1st April. From 5th May onwards, the number of newly infected cases was ≥150, daily. From 25th March to 16th April the number of deaths related to COVID-19 was detected to be between 100 and 250. In fact, till 24th April, more people were killed by coronavirus in London than died during the worst four-week period of aerial bombing of the city during the Blitz in World War Two (BBC, 2020d). As of 16th July total death count in London was 6123 which was maximum in the UK. It is interesting that peak cases for London were during the lockdown condition. Overcrowded can be the possible reason for spreading this COVID-19 s badly in London. Where social distancing is essential, having space issue in a city like London dominated.

Fig. 3.

Observed cases of COVID-19 in London, UK (dated: 9th Feb – 16th July 2020).

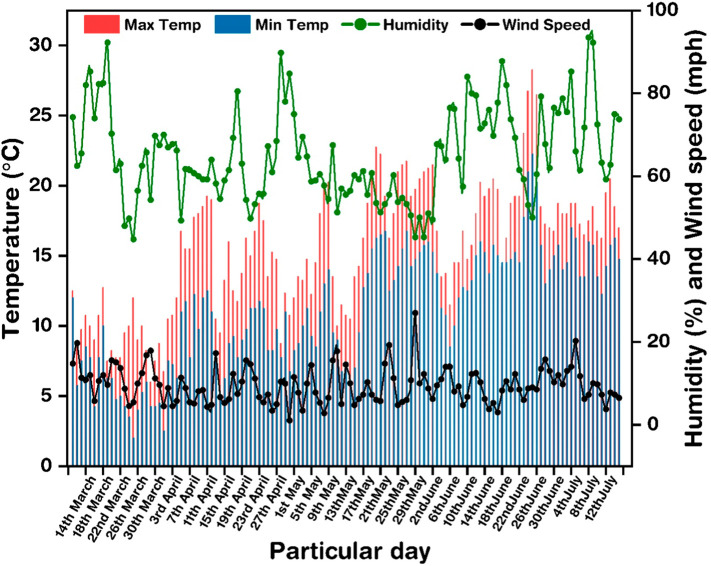

Fig. 4 shows the maximum and minimum temperature, humidity, and wind speed in London between 11th March and 16th July. The highest maximum temperature was 28 °C on 25th June and the lowest maximum temperature was 6 °C on 29th March. Humidity varied between 44% to 92%. Wind speed for those days speckled between 2 and 23 mph.

Fig. 4.

Variation of maximum temperature, minimum temperature, humidity, and wind speed for 11th of March 2020 to 16th July 2020.

Two different dates were selected to analyze the COVID-19 transmission in London, UK. First, data up to 10th May (first writing of the article) and then up to 16th July (writing during revision) and the outcome from both results were interesting. Table 1 indicates the empirical estimation using the Pearson correlation method. Both maximum and minimum temperatures have a moderate negative correlation to the number of new confirmed and death cases(for study up to 16th July). Table 2 illustrates the Kendall correlation which indicates a moderate negative correlation between the maximum and minimum temperatures to the number of new confirmed and death cases (for study up to 16th July). Further, Table 3 specifies the Spearman correlation similarly hinting the moderate negative correlation between maximum and minimum temperatures with the number of new confirmed cases and new deaths (for study up to 16th July). In all the three tables there was a negligible positive correlation between maximum temperature and new cases and new deaths and negligible negative correlation between minimum temperature and new cases and new deaths (for study up to 10th May). From three correlation using data till 10th May, it appeared that temperature has more or less no effect (due to negligible correlation) on COVID 19 cases and deaths. However, for study up to 16th July the result shows that temperature has a moderate negative correlation with the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths which indicate that as temperature increases, new COVID-19 cases, as well as new deaths, decrease. Humidity and wind speed were not strongly correlated with any of new cases or new deaths cases in both studies.

Table 1.

Empirical results using Pearson correlation coefficient.

| New case (10th May) | New case (16th July) | New deaths (10th May) | New deaths (16th July) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum temp | 0.052845 | −0.5182 | 0.108409 | −0.3238 |

| Minimum temp | −0.11075 | −0.674 | −0.09906 | −0.4738 |

| Humidity | −0.25156 | −0.1664 | −0.35567 | −0.1765 |

| Wind speed | −0.13921 | −0.1211 | −0.16509 | −0.078 |

Table 2.

Empirical results using Kendall correlation coefficient.

| New case (10th May) | New case (16th July) | New Deaths (10th May) | New deaths (16th July) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum temp | 0.03913 | −0.3931 | 0.071174 | −0.3238 |

| Minimum temp | −0.08045 | −0.5203 | −0.08165 | −0.4738 |

| Humidity | −0.14541 | −0.136 | −0.22247 | −0.1765 |

| Wind speed | −0.09116 | −0.067 | −0.15008 | −0.078 |

Table 3.

Empirical results using Spearman correlation coefficient.

| New case (10th May) |

New case (16th July) |

New deaths (10th May) |

New deaths (16th July) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum temp | 0.054483 | −0.58 | 0.104025 | −0.4919 |

| Minimum temp | −0.11742 | −0.7428 | −0.11137 | −0.6893 |

| Humidity | −0.24857 | −0.234 | −0.34941 | −0.2921 |

| Wind speed | −0.13921 | −0.1011 | −0.20848 | −0.1143 |

Till 10th of May data, findings were similar to the previously reported work, which performed a similar analysis for New York City (Bashir, Ma, Bilal, & D. & Bashir, M., 2020) and Jakarta (Tosepu et al., 2020). Also, few reported works showed humidity and temperature both have an impact on the transmission of COVID-19 (Sajadi et al., 2020) and mortality rate from COVID-19 (Ma et al., 2020; Poole, 2020). Wang, Wang, Chen, & Qin (2020) reported that the outbreak of COVID-19 from Wuhan had a strong correlation between weather conditions and disease transmission. Further wind speed, humidity, and air quality have also impacted the transmission as reported by (Chen, Liang, et al., 2020; Chen, Zhou, et al., 2020). Data set from Feb to 16th July 2020 showed a negative association between climatic parameters and COVID-19 cases in London.

This work has a limitation as several other factors that influence the COVID-19 should not be ignored. This virus created disease needs more depth analysis based on resistivity from viruses, population mobility, endurance, individual health factors which include hand washing habits, personal hygiene, and use of hand sanitizers. It is more rational to investigate worldwide meteorological data and COVID-19 cases to investigate if there is any strong relation or not. City-level factors which include the feasible control policy of COVID-19, the urbanization rate and the availability of medical resources, can affect the COVID-19 transmission which may influence the results.

3.2. Distance dependency

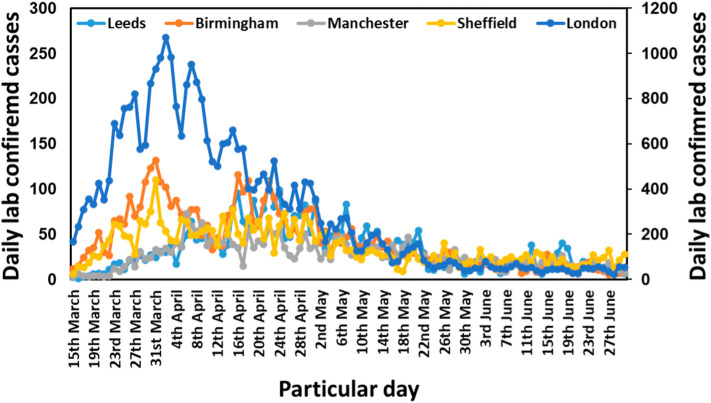

Fig. 5 illustrates the daily lab confirmed cases for London, Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester and, Sheffield. London had the maximum cases on 2nd April which crossed over 1000. For Birmingham Leeds, Manchester and Sheffield, maximum cases were 132, 109, 73 and 110, on 31st March, 22nd April, 6th April and 31st March respectively.

Fig. 5.

Daily cases for London, Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield from 15th March to 30th June 2020.

From the fixed effects (Table 4 ), it is observed that the estimate of the coefficient of distance is −25.08761. To check whether the effect of distance on COVID-19 cases is significant or not, null hypothesis was employed (b3 = 0) against alternative hypothesis (b3 ≠ 0), where b3 is the change in daily lab confirmed cases for a unit change in distance. Since p-value for this test is less than 0.05, null hypothesis was rejected at 5% level of significance and conclude that the effect of distance from London (in km) on daily lab confirmed cases is significant. Also, since the coefficient estimate is negative, it can be concluded that as the distance increases from London, the number of cases decreases.

Table 4.

Fixed effect results for distance dependency from London to other four cities.

| Fixed effects: | Estimate | Std. error | t Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 32.93176 | 9.59686 | 3.432 |

| Time | 0.74978 | 2.33046 | 0.322 |

| Time^2 | −0.01015 | 0.01657 | −0.613 |

| Distance | −25.08761 | 5.01678 | −5.001 |

| Population | 4.89825 | 3.93665 | 1.244 |

| Distance:population | −9.84526 | 5.32608 | −1.848 |

From the random effects (Table 5 ), it is observed that the standard deviation of the intercept when grouped by city is 18.55223 which is significantly different from 0. It is the variability of the intercept across different cities. This shows that each and every city has its own individual specific effect on the number of COVID-19 cases reported daily. On the basis of the data, it can also be concluded that all cities in the UK will have their own individual effect on the daily cases confirmed since all cities are different from each other in a lot of ways. The standard deviation across time is 4.65615 which is not very significantly different from 0. It indicates variability in the slope of time across cities. This shows that different cities will have more or less the same variability in the growth of COVID-19 cases over time. Distance from epicentre Wuhan to other cities also showed the same outcome (Liu, 2020).

Table 5.

Random effect results for distance dependency from London to other four cities.

| Random effects | Name | Variance | Std. dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | (Intercept) | 3.442e+02 | 18.55223 |

| City | Time | 2.168e+01 | 4.65615 |

| I(time^2) | 1.095e-03 | 0.03309 |

4. Discussion

As previously coronavirus caused respiratory disease, temperature and humidity came into the scenario to realize if it has any impact on COVID-19 transmission or not. However, after several investigations which were conducted in different places around the world considering different cities, no concrete dependency on COVID-19 transmission and climatic parameters were established. Also, in this work, two different outcomes were observed. Till 10th of May, with temperature, a negligible correlation was found while data till 16th July, the COVID-19 case number decreases with temperature. Greater distance from London to other cities showed a diminution of COVID-19 cases.

It is evident that London was the worst hit place from COVID-19 in the UK. Also, other major cities in the world including Delhi, London, Los Angeles, Milan, Mumbai, New York, Rome, São Paulo, Seoul and Wuhan had the noteworthy number of COVID-19 cases (Ghosh, Nundy, & Mallick, 2020; Ren, 2020; Her, 2020; BBC, 2020b; Jones, 2020). COVID-19 disease has been transmitted in all regions of the world, from cold and dry, to hot and humid climates(Ghosh et al., 2020). Thus, the reason for transmission may not be the climate but the high population density (WHO, 2020a), which is a quite common factor in big cities. According to WHO, COVID-19 spread easily through droplets from mouth or nose from an infected person to another person if they breathe in these droplets. These heavy droplets have the ability to travel at least 1 m. Hence, maintaining social distance is essential to limit transmission. Thus, the highly populated city (in this case London) posses the maximum risk of transmission (Stier, Berman, & Bettencourt, 2020). COVID-19 has a reproductive number (R) greater than 1, which is above the threshold of an epidemic (Gov.UK, 2020b). Product of contact rate and infectious period indicates the reproductive number. Contact rate is a property of the population, essentially measuring the number of social contacts that can transmit the disease per unit. Reduction of social contact, can significantly reduce the R and thus transmission. Hence, it can be seen that London got success after implementation of the lockdown measure.

The second wave in different cities is already in place. The Segria region in Catalonia, Spain re-entered to an indefinite partial lockdown on July 4, following a significant spike in cases and COVID-19 hospitalisations. The city of Leicester in the United Kingdom has gone into a second lockdown after it accounted for 10% of all positive COVID-19 cases in the country at the end of June (Courten, Pogrmilovic, & Calder, 2020; Nazareth et al., 2020). From 31st July Manchester will experience another lockdown for the second wave. As the climate has not found to be significantly responsible for COVID-19 transmission, stringent urban policymaking is essential which can play a key role to abate the transmission by allowing strict social distance measure.

Densely populated work environment, house and public transport for commuting are the common features of every urban city. The influx of people from rural areas results poor in housing condition with poor sanitation facilities, an insufficient supply of freshwater and ineffective ventilation systems, which in turn increase the outbreak risks. Rapid urbanization can lead encroachment of natural habitats and create a provision of closer encounters with wildlife which also provides opportunities for zoonotic infections (Lee et al., 2020). To avoid the second wave peek, maintaining the social distance and isolation from mass gathering should be followed everywhere specially in the big crowded metropolitan cities. Abiotic objects in the built environment is a viral transmission reservoir (Ong et al., 2020). Corona virus which is responsible for COVID-19 is active and can be detectable up to 3 h on aerosol, copper for 4 h, carboard for 24 h and 2 to 3 days on stainless steel and plastic (Doremalen et al., 2020). Hence, the improvement of building environment is essential as closed and confined space increase the chances of the COVID-19 transmission (Dietz et al., 2020). The recent trend to enhance collaboration and innovation among employees, offices are made as open space type to increase connectivity while private offices may decrease connectivity (Dietz et al., 2020). This open space office idea should be changed because of the COVID-19. Also due to urban sprawl, most of the buildings suffer from insufficient daylight and fresh air, and building interiors rely only on artificial light (Ghosh & Norton, 2018) which should be changed by allowing the UV and visible spectral ranges to reduce bacterial activity (Fahimipour et al., 2018; Schuit et al., 2020). WHO recommended that building should have higher ventilation rate and if possible to open the window as much as possible to allow external ambient air (WHO, 2020b). Thus, the growth of urbanization should be taken place by keeping more green space and space between buildings to limit the transmission for any infectious disease in future. Responsible transport such as avoid crowded public transport and travel only if it is necessary will play an indispensable task to break the transmission chain. Hence, if possible walking and cycling can be an alternative mode of transport from now on (Budd & Ison, 2020; De Vos, 2020). However, big cities like London it's a real challenge where in every 15 min 325,000 people use underground (BBC, 2020a). Use of walking and cycling has already been increased in Budapest (Bucsky, 2020). As the disease is now well established in the human population, efforts should be focused on reducing transmission and treating patients.

5. Conclusion

Transmission of COVID-19 pandemic for London and other four cities (Birmingham, Leeds. Manchester, Sheffield) was realized using statistical analysis from the urban context. Climatic parameters dependency on London's COVID-19 number and distance from London to other four cities were evaluated using Kendall, Pearson, Spearman and mixed effect model respectively. COVID-19 data were collected from online data service of national health service UK, and climatic data were collected from an online platform of Time and Date AS. Using Pearson, Kendall, and Spearman correlation coefficient the collected data from 11th March to 10th May and from 11th March to 16th of July were studied empirically. More or less negligible correlation between the number of confirmed new cases with minimum and maximum temperature was established till the data of 10th May, while considering data up to 16th July, different outcome was observed. Hence, it is clear that climatic parameter is not a useful tool to understand the transmission of COVID-19. This hypothesis well matched with WHO direction where it is clearly mentioned that there is no strong evidence which can claim that weather (short term variations in meteorological conditions) or climate (long-term averages) strongly influence COVID-19 transmission. As transmission through person to person is well established, for big cities attention should be paid for social distancing and treatment. Also, a clear urban policy should be taken place now as there is a threat for the second wave of COVID-19 and for any pandemic in future.

Funding

This work didn't receive any specific grant.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Conceptualization: A.G.; Data curation: A.G.; Investigation; AG, SN,SG; Project administration: AG,TM; Resources: AG,SN,SG,TM; Supervision: AG,TM; Roles/Writing - original draft: AG; Writing - review & editing: AG,SN,SG,TM.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- BBC. (2020a). Coronavirus: How will transport need to change? doi:https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/explainers-52534135.

- BBC. (2020b). Coronavirus: The world in lockdown in maps and charts. BBC. doi:https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-52103747.

- BBC. (2020d). Coronavirus: Which regions have been worst hit? doi:https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/52282844.

- For National Statistics, O. (2020). Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. doi:https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland.

- Gov.UK. (2020a). Coronavirus (COVID-19) cases in the UK. doi:https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/archive.

- Gov.UK. (2020b). The R number and growth rate in the UK. doi:https://www.gov.uk/guidance/the-r-number-in-the-uk#latest-r-number-and-growth-rate.

- Nazareth J, Minhas, J. S., Jenkins, D. R., Sahota, A., Khunti, K., Halder, P., & Pareek, M. (2020). Early lessons from a second COVID-19 lockdown in Leicester, UK. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, (January), 19–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31490-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- The Guardian. (2020). Calls for inquiry as UK reports highest Covid-19 death toll in Europe. doi:https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/05/uk-coronavirus-death-toll-rises-above-32000-to-highest-in-europe.

- WHO. (2020a). Climate change and COVID-19. doi:https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-on-climate-change-and-covid-19#:~:text=There%20is%20no%20evidence%20of,transmission%20and%20treating%20patients.

- WHO. (2020b). Ventilation and air conditioning and COVID-19. doi:https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-ventilation-and-air-conditioning-and-covid-19.

- Aiello A.E., Simanek A.M., Eisenberg M.C., Walsh A.R., Davis B., Volz E.…Monto A.S. Design and methods of a social network isolation study for reducing respiratory infection transmission: The eX-FLU cluster randomized trial. Epidemics. 2016;15:38–55. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrus A., Field E., Gonzalez R. Loss in the time of cholera: Long-run impact of a disease epidemic on the urban landscape. American Economic Review. 2020;110(2):475–525. doi: 10.1257/aer.20190759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, M. B., & Naimi, B. (2020). Spread of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus likely to be constrained by climate. MedRxiv, 2020.03.12.20034728. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.12.20034728. [DOI]

- Bashir M.F., Ma B., Bilal, Komal B., Bashir M.A., Tan D., Bashir M. Correlation between climate indicators and COVID-19 pandemic in New York, USA. Science of the Total Environment. 2020;728:138835. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BBC. (2020c). Coronavirus: UK donates £20m to speed up vaccine. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-51352952.

- BBC. (2020e). Coronavirus pandemic: Tracking the global outbreak. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-51235105.

- Bucsky P. Modal share changes due to COVID-19: The case of Budapest. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2020;100141 doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd L., Ison S. Responsible transport: A post-COVID agenda for transport policy and practice. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2020;6:100151. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London Loves Business. (2020). London is the epicentre in UK with hundreds infected with coronavirus. Retrieved from https://londonlovesbusiness.com/london-is-the-epicentre-in-uk-with-hundreds-infected-with-coronavirus/.

- Chakraborty I., Maity P. COVID-19 outbreak: Migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Science of the Total Environment. 2020;728:138882. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B., Liang, H., Yuan, X., Hu, Y., Xu, M., Zhao, Y., … Zhu, X. (2020). Roles of meteorological conditions in COVID-19 transmission on a worldwide scale. MedRxiv, 11, 2020.03.16.20037168. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.16.20037168. [DOI]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y.…Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contini D., Costabile F. Does air pollution influence COVID-19 outbreaks? Atmosphere. 2020;11(4):377. doi: 10.3390/ATMOS11040377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courten, M., Pogrmilovic, B.K., & Calder, R.V. (2020). Coronavirus lockdown, relax, repeat: How world cities are returning to Covid-19 restrictions. doi:https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/300057288/coronavirus-lockdown-relax-repeat-how-world-cities-are-returning-to-covid19-restrictions.

- AS, Ti, D. Past weather in London, England, United Kingdom. 2020. https://www.timeanddate.com/weather/uk/london/historic?month=4&year=2020 Retrieved from.

- De Vos J. The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behavior. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2020;5:100121. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, L., Horve, P.F., Coil, D.A., Fretz, M., Eisen, J.A., & Wymelenberg, K.V.D. (2020). 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: Built environment considerations to reduce transmission. Applied and Environmental Scicences, (April), 1–13.

- Doremalen, N., Morris, D., Holbrook, M. G., Gamble, A., Williamson, B. ., Tamin, A., … Wit, E. D. (2020). Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. The New England Journal of Medicine, 0–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fahimipour A.K., Hartmann E.M., Siemens A., Kline J., Levin D.A., Wilson H.…Van Den Wymelenberg K. Daylight exposure modulates bacterial communities associated with household dust 06 biological sciences 0605 microbiology. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, N. M., Laydon, D., Nedjati-Gilani, G., Imai, N., Ainslie, K., Baguelin, M., … Ghani, A. C. (2020). Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. Imperial.Ac.Uk, (March), 3–20. doi:10.25561/77482.

- Ghosh A., Norton B. Advances in switchable and highly insulating autonomous (self-powered) glazing systems for adaptive low energy buildings. Renewable Energy. 2018;126:1003–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2018.04.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A., Nundy, S., & Mallick, T. K. (2020). How India is dealing with COVID-19 pandemic. Sensors International, 1(July), 100021. doi: 10.1016/j.sintl.2020.100021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Guardian, T. (2020). 95,000 have entered UK from abroad during coronavirus lockdown. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/13/95000-have-entered-uk-from-abroad-during-coronavirus-lockdown.

- Her M. Repurposing and reshaping of hospitals during the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea. One Health. 2020;10(May):100137. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Song C., Xu C., Jin G., Chen Y., Xu X.…Shen H. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Science China. Life Sciences. 2020;63(5):706–711. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y.…Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D.S. History in a crisis — Lessons for Covid-19. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(18):1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2004361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S., Cheng S.O. What led to the UK’s COVID-19 death toll? – An insight into the mistakes made and the current situation. International Journal of Surgery. 2020;79(June):327–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W.H., Li Y., Peng M.W., Kong D.G., Yang X.B., Wang L., Liu M.Q. SARS-CoV-2 detection in patients with influenza-like illness. Nature Microbiology. 2020;5(May) doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0713-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupferschmidt K., Cohen J. Can China strategy work. Science. 2020;367 doi: 10.1126/science.367.6482.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau H., Khosrawipour V., Kocbach P., Mikolajczyk A., Ichii H., Zacharski M.…Khosrawipour T. The association between international and domestic air traffic and the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2020;53(3):467–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.Y., Bedford V.L., Roberts M.S., Carley K.M. Virtual epidemic in a virtual city: Simulating the spread of influenza in a US metropolitan area. Translational Research. 2008;151(6):275–287. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V.J., Ho M., Kai C.W., Aguilera X., Heymann D., Wilder-Smith A. Epidemic preparedness in urban settings: New challenges and opportunities. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(5):527–529. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30249-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y.…Feng Z. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie P.J., Samson A., Li A., Adams K., Capstick R., Barlow G.D.…the Airborne HCID Network Novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19): The first two patients in the UK with person to person transmission. Journal of Infection. 2020;80(5):578–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. Emerging study on the transmission of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) from urban perspective: Evidence from China. Cities. 2020;103(March):102759. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Zhao Y., Liu J., He X., Wang B., Fu S.…Luo B. Effects of temperature variation and humidity on the death of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Science of the Total Environment. 2020;724:138226. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahase E. Covid-19: UK starts social distancing after new model points to 260 000 potential deaths. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2020;368(March):m1089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menebo M.M. Temperature and precipitation associate with Covid-19 new daily cases: A correlation study between weather and Covid-19 pandemic in Oslo, Norway. Science of the Total Environment. 2020;737:139659. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss P., Barlow G., Easom N., Lillie P., Samson A. Lessons for managing high-consequence infections from first COVID-19 cases in the UK. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227) doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30463-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H., Managi S. Airport risk of importation and exportation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Transport Policy. 2020;96(April):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS. (2020). COVID-19 Daily Deaths. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/covid-19-daily-deaths/.

- Nishiura H., Kobayashi T. Estimation of the asymptomatic ratio of novel coronavirus infections (COVID-19) International Journal of Infectiouc Diseases. 2020;94(January):154–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly K., Auzenbergs M., Jafari Y., Liu Y., Flasche S., Lowe R. Effective transmission across the globe: The role of climate in COVID-19 mitigation strategies. CMMID Repository. 2020;3550308(20):1–4. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30106-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office P.M. PM announces easing of lockdown restrictions: 23 June 2020. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-announces-easing-of-lockdown-restrictions-23-june-2020

- Ong S.W.X., Tan Y.K., Chia P.Y., Lee T.H., Ng O.T., Wong M.S.Y., Marimuthu K. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020;323(16):1610–1612. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orimoloye I.R., Mazinyo S.P., Kalumba A.M., Ekundayo O.Y., Nel W. Implications of climate variability and change on urban and human health: A review. Cities. 2019;91(December 2018):213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock A.M., Roderick P., Cheng K.K., Pankhania B. Covid-19: Why is the UK government ignoring WHO’s advice? The BMJ. 2020;368(March):1–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole L. Seasonal influences on the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID19), causality, and forecastabililty (3-15-2020) SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020;2 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3554746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Population L. London Population. 2020:2020. https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/london-population/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Prata D.N., Rodrigues W., Bermejo P.H. Temperature significantly changes COVID-19 transmission in (sub)tropical cities of Brazil. Science of the Total Environment. 2020;729:138862. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X. Pandemic and lockdown: A territorial approach to COVID-19 in China, Italy and the United States. Eurasian Geography and Economics. 2020;00(00):1–12. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2020.1762103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sajadi, M. M., Habibzadeh, P., Vintzileos, A., Miralles-wilhelm, F., & Amoroso, A. (2020). Temperature, humidity, and latitude analysis to predict potential spread and seasonality for COVID-19, (410), 6–7. Retrieved from 10.2139/ssrn.3550308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schuit M., Gardner S., Wood S., Bower K., Williams G., Freeburger D., Dabisch P. The influence of simulated sunlight on the inactivation of influenza virus in aerosols. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;221(3):372–378. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw R., Kim Y., Hua J. Governance, technology and citizen behavior in pandemic: Lessons from COVID-19 in East Asia. Progress in Disaster Science. 2020;6:100090. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi C., Alsafi Z., O’Neill N., Khan M., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A.…Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) International Journal of Surgery. 2020;76(February):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J.H., Finucane M.L., Fox J.M., Saksena S., Sultana N. Emerging infectious disease, the household built environment characteristics, and urban planning: Evidence on avian influenza in Vietnam. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2020;193(August 2017) doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stier, A. J., Berman, M. G., & Bettencourt, L. M. A. (2020). COVID-19 attack rate increases with city size. Medrxiv, 1–23. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.22.20041004. [DOI]

- Tay M.Z., Poh C.M., Rénia L., MacAry P.A., Ng L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: Immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosepu R., Gunawan J., Effendy D.S., Ahmad L.O.A.I., Lestari H., Bahar H., Asfian P. Correlation between weather and Covid-19 pandemic in Jakarta, Indonesia. Science of the Total Environment. 2020;725 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. (2020). Neighborhood foreclosures and health disparities in the U.S. cities. Cities, 97(November 2019), 102526. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.102526. [DOI]

- Wang J., Tang K., Feng K., Lv W. High temperature and high humidity reduce the transmission of COVID-19. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3551767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang Y., Chen Y., Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020;92(6):568–576. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Jing W., Liu J., Ma Q., Yuan J., Wang Y.…Liu M. Effects of temperature and humidity on the daily new cases and new deaths of COVID-19 in 166 countries. Science of the Total Environment. 2020;729:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Zhu Y. Association between ambient temperature and COVID-19 infection in 122 cities from China. Science of the Total Environment. 2020;724:138201. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.W., Wu X.X., Jiang X.G., Xu K.J., Ying L.J., Ma C.L.…Li L.J. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: Retrospective case series. The BMJ. 2020;368(January):1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Pan J., Liu Z., Meng X., Wang W., Kan H., Wang W. No association of COVID-19 transmission with temperature or UV radiation in Chinese cities. European Respiratory Journal. 2020;55(5):7–9. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00517-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., Litvinova, M., Liang, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, W., Zhao, S., … Yu, H. (2020). Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science, 8001(April), eabb8001. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W.…Shi Z.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J.…Tan W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]