Bacterial infections are frequently caused by more than one species, and such polymicrobial infections are often considered more virulent and more difficult to treat than the respective monospecies infections. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus are among the most important pathogens in polymicrobial infections, and their cooccurrence is linked to worse disease outcome. There is great interest in understanding how these two species interact and what the consequences for the host are. While previous studies have mainly looked at molecular mechanisms implicated in interactions between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, here we show that ecological factors, such as strain background, species frequency, and environmental conditions, are important elements determining population dynamics and species coexistence patterns. We propose that the uncovered principles also play major roles in infections and, therefore, proclaim that an integrative approach combining molecular and ecological aspects is required to fully understand polymicrobial infections.

KEYWORDS: interspecies interactions, polymicrobial infections, microbial communities, opportunistic infections

ABSTRACT

Bacterial communities in the environment and in infections are typically diverse, yet we know little about the factors that determine interspecies interactions. Here, we apply concepts from ecological theory to understand how biotic and abiotic factors affect interaction patterns between the two opportunistic human pathogens Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus, which often cooccur in polymicrobial infections. Specifically, we conducted a series of short- and long-term competition experiments between P. aeruginosa PAO1 (as our reference strain) and three different S. aureus strains (Cowan I, 6850, and JE2) at three starting frequencies and under three environmental (culturing) conditions. We found that the competitive ability of P. aeruginosa strongly depended on the strain background of S. aureus, whereby P. aeruginosa dominated against Cowan I and 6850 but not against JE2. In the latter case, both species could end up as winners depending on conditions. Specifically, we observed strong frequency-dependent fitness patterns, including positive frequency dependence, where P. aeruginosa could dominate JE2 only when common (not when rare). Finally, changes in environmental (culturing) conditions fundamentally altered the competitive balance between the two species in a way that P. aeruginosa dominance increased when moving from shaken to static environments. Altogether, our results highlight that ecological details can have profound effects on the competitive dynamics between coinfecting pathogens and determine whether two species can coexist or invade each others’ populations from a state of rare frequency. Moreover, our findings might parallel certain dynamics observed in chronic polymicrobial infections.

IMPORTANCE Bacterial infections are frequently caused by more than one species, and such polymicrobial infections are often considered more virulent and more difficult to treat than the respective monospecies infections. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus are among the most important pathogens in polymicrobial infections, and their cooccurrence is linked to worse disease outcome. There is great interest in understanding how these two species interact and what the consequences for the host are. While previous studies have mainly looked at molecular mechanisms implicated in interactions between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, here we show that ecological factors, such as strain background, species frequency, and environmental conditions, are important elements determining population dynamics and species coexistence patterns. We propose that the uncovered principles also play major roles in infections and, therefore, proclaim that an integrative approach combining molecular and ecological aspects is required to fully understand polymicrobial infections.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria typically live in complex multispecies communities in the environment and are frequently associated with host organisms (1–3). The same holds true for disease, as it has been increasingly recognized that a majority of bacterial infections are polymicrobial, meaning that they are caused by more than one bacterial species (4, 5). There is great interest in understanding how bacteria interact and how interactions affect a community and the associated hosts (6–8). At the mechanistic level, a multitude of ways that bacterial species can interact have been unraveled, and such mechanisms include cross-feeding, quorum sensing-based signaling, toxin-mediated interference, and physical interactions via contact-dependent systems (e.g., type VI secretion system) (9–11). In the context of disease, a key question is how interactions affect species successions in chronic infections and whether multispecies infections are more virulent and more difficult to treat than the respective monospecies infections, as is commonly assumed (5, 12–14).

Studying interactions between the two opportunistic human pathogens Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus has emerged as a popular and relevant model system (15–17). The reason for this is that the two species often cooccur in infections, including cystic fibrosis (CF) lung and wound infections (18–20). Results from laboratory experiments suggest that P. aeruginosa is the superior species, suppressing growth of S. aureus (21–23); indeed, P. aeruginosa seems to be a well-equipped competitor. For example, it has been shown that 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline N-oxide (HQNO) released by P. aeruginosa inhibits the electron transport chain of S. aureus and induces the formation of small colony variants (SCVs) (22, 24). Furthermore, the P. aeruginosa endopeptidase LasA is capable of lysing S. aureus cells, a process that releases iron into the environment, potentially providing a direct benefit to P. aeruginosa (21, 25). While it was observed that experimental coinfections of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus seem to be more virulent than the respective monospecies infections (26, 27), evolutionary studies revealed that P. aeruginosa can adapt to the presence of S. aureus (28) and become more benign in the context of chronic coinfections (29, 30). Moreover, of clinical relevance is the observation that P. aeruginosa and S. aureus exhibited increased antibiotic resistance or tolerance when cocultured compared to being cultured alone (31–33).

In this study, we follow a complementary approach to examine how biotic and abiotic ecological factors influence interactions between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Previous work has primarily focused on the molecular mechanisms driving interactions between specific strain pairs under defined laboratory conditions. Here, we hypothesize that not only molecular mechanisms but also ecological factors will have a major impact on species interactions, particularly on community composition and temporal dynamics between species. To test our predictions, we used P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 as our focal strain and asked how (competitive) interactions with S. aureus vary when manipulating (i) the genetic background of S. aureus, (ii) the frequency of S. aureus in competition with P. aeruginosa, and (iii) environmental (culturing) conditions.

To vary the genetic background of S. aureus, we competed P. aeruginosa against the three different S. aureus strains Cowan I, 6850, and JE2. These strains fundamentally differ in several characteristics (Table 1). Cowan I is a methicillin-sensitive S. aureus strain (MSSA), which is highly invasive toward host cells, noncytotoxic, and defective in the accessory gene regulator (agr) quorum-sensing system (34). 6850 is another MSSA strain that is highly invasive, cytotoxic, and hemolytic (35–37). Finally, JE2 is a methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) USA300 strain that is highly virulent, cytotoxic, and hemolytic (38, 39). Given the tremendous differences between these S. aureus strains, we expect P. aeruginosa performance in competition with S. aureus to vary substantially.

TABLE 1.

P. aeruginosa and S. aureus strains used for this study

| Strain name | Origin | Descriptiona | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |||

| PAO1::gfp | Wound | Constitutive GFP expression from the chromosome (attTn7::Ptac-GFP) | Our laboratory |

| Staphylococcus aureus | |||

| Cowan I | Septic arthritis | MSSA isolate; highly invasive, but not cytotoxic; agr defective | ATCC 12598 |

| 6850 | Osteomyelitis | MSSA isolate; highly invasive, cytotoxic, and hemolytic | ATCC 53657 |

| JE2 | Skin and soft tissue infection | USA300 CA-MRSA isolate; highly virulent, cytotoxic, and hemolytic | NARSA |

CA-MRSA, community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus; agr, accessory gene regulator.

To manipulate strain frequency, we competed P. aeruginosa against S. aureus at three different starting frequencies (1:9, 1:1, and 9:1). Frequency-dependent fitness effects occur in many microbiological systems (40–43). A common pattern is that species have a relative fitness advantage when rare in a population but not when common (so-called negative frequency dependence). This phenomenon can lead to stable coexistence of competitors. On the other hand, the fitness of a species can also be positive frequency dependent, which means that a species is dominant when common in the community but not when rare. An important consequence of this pattern is that initially rare species cannot invade an established population.

To manipulate environmental conditions, we changed simple parameters of our culturing conditions. First, we compared the performance of P. aeruginosa against S. aureus strains in shaken liquid versus viscous medium. Increased environmental viscosity has been shown to increase spatial structure, thereby decreasing strain interaction rates (44–46). Second, we compared the performance of P. aeruginosa against S. aureus in shaken versus static environments. While static conditions also reduce strain mixing, it further leads to a more heterogeneous environment characterized by gradients from the aerated air-liquid interface down to the microoxic bottom of a culture (47, 48).

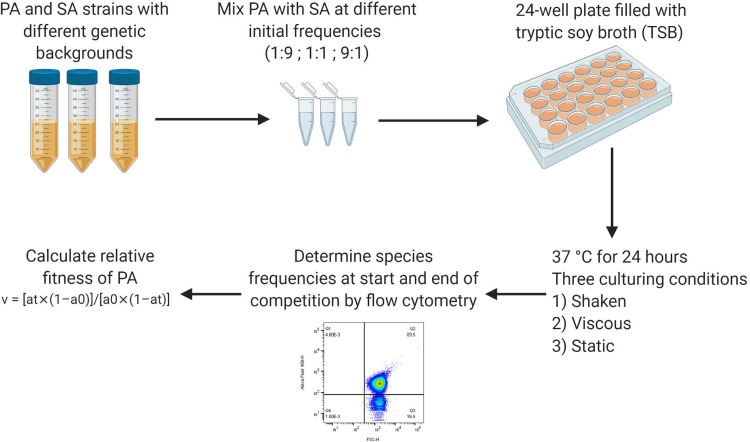

In a first set of experiments, we assessed the growth performance of all strains in monoculture under the three different environmental culturing conditions used. Basic growth differences between strains could induce frequency shifts in cocultures even in the absence of direct interactions. We then performed high-throughput 24-h batch culture competition experiments between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus using a full-factorial design. All three species combinations were competed at all three starting frequencies under all three environmental conditions (Fig. 1 shows an illustration of the workflow). Finally, we monitored the temporal dynamics between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus over 5 days to assess whether results from 24-h competitions are predictive for more long-term dynamics between species and whether species coexistence is possible.

FIG 1.

Workflow for the competition experiments. Bacterial overnight cultures were grown in 10 ml TSB in 50-ml falcon tubes for ∼16 h at 37°C and 220 rpm, with aeration. After washing and adjustment of OD600 to obtain similar cell numbers for all strains, strain pairs (P. aeruginosa-Cowan I, P. aeruginosa-6850, and P. aeruginosa-JE2) were mixed at three different volumetric starting frequencies (1:9, 1:1, and 9:1). Flow cytometry was used to measure the actual starting frequencies. Competitions were started with diluted cultures (OD600 of 10−5) in 24-well plates filled with 1.5 ml TSB per well. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C under three different culturing conditions: shaken (170 rpm), viscous (170 rpm plus 0.2% agar in TSB), and static. After the 24-h competition period, final strain frequencies were measured for each replicate by flow cytometry. Using the initial and final strain frequencies, the relative fitness (v) of the focal strain P. aeruginosa was calculated as v = [at × (1 − a0)]/[a0 × (1 − at)], where a0 and at are the initial and final frequencies of P. aeruginosa, respectively. PA, P. aeruginosa; SA, S. aureus.

(This article was submitted to a preprint archive [49].)

RESULTS

P. aeruginosa grows better than S. aureus in monoculture.

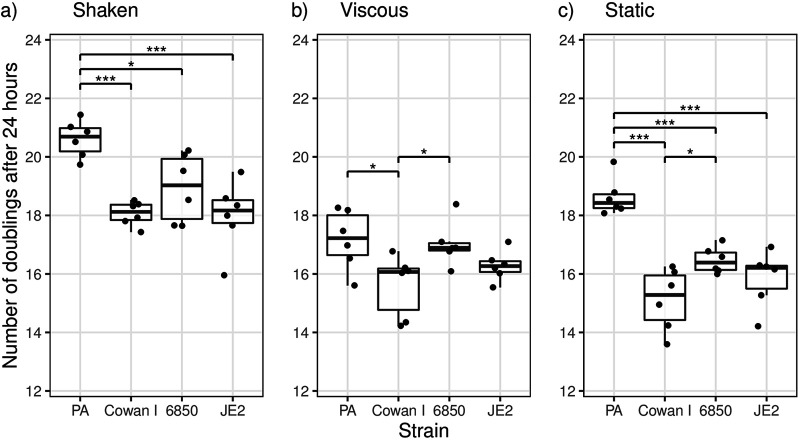

We used tryptic soy broth (TSB) as the standard medium for all our assays. In this medium, we found that the number of doublings varied significantly among strains during a 24-h growth cycle under all conditions tested (analysis of variance [ANOVA]; shaken, F3,20 = 10.71, P = 0.0002; viscous, F3,20 = 4.12, P = 0.0199; static, F3,20 = 20.75, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2; also see Table S1 in the supplemental material for the full statistical analysis). Under shaken conditions, P. aeruginosa had the highest number of doublings (20.6 ± 0.63, means ± standard deviations), followed by S. aureus strains 6850 (18.9 ± 1.16), Cowan I (18.1 ± 0.41), and JE2 (18.0 ± 1.18). While P. aeruginosa grew significantly better than all S. aureus strains, the number of doublings did not differ between the three S. aureus strains (Tukey’s honestly significant difference [HSD] pairwise comparisons: Cowan I versus 6850, adjusted P value [Padj] of 0.3673; 6850 versus JE2, Padj = 0.3096; Cowan I versus JE2, Padj = 0.9994). Due to its moderate growth advantage, P. aeruginosa is expected to slightly increase in frequency in competition with S. aureus strains under shaken conditions, even in the absence of any direct species interactions.

FIG 2.

The number of doublings in monoculture for P. aeruginosa PAO1 (PA) was higher than those for the three S. aureus strains (Cowan I, 6850, and JE2) under most conditions. Strains were grown as monocultures in TSB for 24 h at 37°C under the same conditions and using the same starting OD600 as those for the competition experiments. The box plots show the median (boldface line) with the first and third quartiles. The whiskers cover 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) or extend from the lowest to the highest value if they fall within 1.5 times the IQR. Data from two independent experiments with three replicates each are shown. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001, pairwise comparisons without bars are not significant.

Under viscous conditions, P. aeruginosa had the highest number of doublings as well (17.2 ± 1.02), followed by 6850 (17.0 ± 0.76), JE2 (16.3 ± 0.52), and Cowan I (15.6 ± 1.06). However, differences in the number of doublings were only significant between P. aeruginosa and Cowan I and between Cowan I and 6850 (Tukey’s HSD pairwise comparisons: P. aeruginosa versus Cowan I, Padj = 0.0265; Cowan I versus 6850, Padj = 0.0496). Thus, based on growth rate differences alone, one would expect P. aeruginosa to increase in frequency in competition with Cowan I but not in competition with the other two S. aureus strains.

Under static conditions, P. aeruginosa again showed the highest number of doublings (18.6 ± 0.64), followed by 6850 (16.5 ± 0.45), JE2 (15.9 ± 0.96), and Cowan I (15.1 ± 1.05). P. aeruginosa grew significantly faster than all three S. aureus strains (Tukey’s HSD pairwise comparisons: P. aeruginosa versus Cowan I, Padj < 0.0001; P. aeruginosa versus 6850, Padj = 0.0009; P. aeruginosa versus JE2, Padj < 0.0001); therefore, one would expect P. aeruginosa to substantially increase in frequency against all three S. aureus strains under static conditions.

Genetic background, strain frequency, and environmental factors all influence competition outcomes.

The full-factorial design allowed us to simultaneously analyze the impact of S. aureus strain genetic background, starting frequency, and culturing condition on the competitive outcomes between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus strains. Our linear statistical model yielded a significant triple interaction between the three manipulated factors (strain genetic background, starting frequency, and culturing condition; analysis of covariance [ANCOVA]: F4,509 = 3.41, P = 0.0091). While this shows that all three manipulated factors influence the competitive outcomes between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus in complex ways, the triple interaction makes it difficult to tease apart the various effects. The statistical procedure for such cases is to split the model into submodels. We followed this approach by first analyzing separate models for each of the three environmental conditions (shaken, viscous, and static) and then split models according to S. aureus strain background to test for differences between environmental conditions.

The competitive ability of P. aeruginosa depends on the S. aureus strain genetic background.

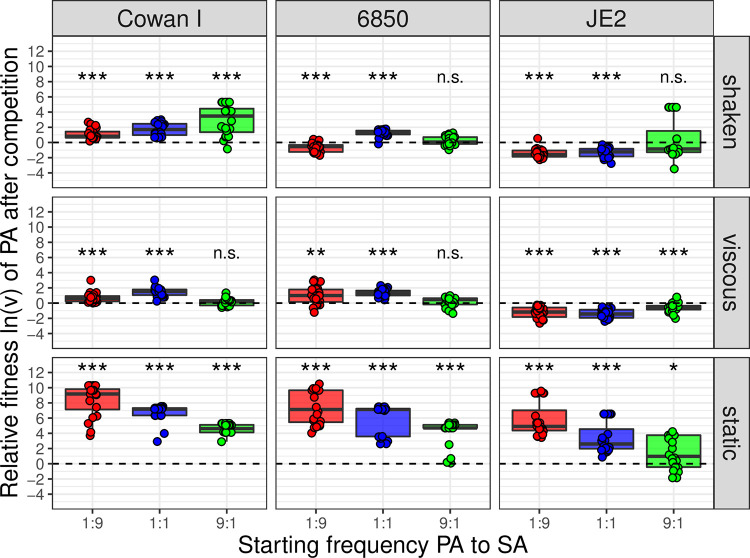

Under all three environmental conditions, we found that the relative fitness of P. aeruginosa significantly depended on the S. aureus strain background (ANCOVA; shaken, F2,170 = 90.87, P < 0.0001; viscous, F2,168 = 116.76, P < 0.0001; static, F2,170 = 56.52, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3). We noted that against Cowan I (Fig. 3, column 1), P. aeruginosa consistently won the competitions across all starting frequencies and culturing conditions. S. aureus strain 6850 (Fig. 3, column 2) turned out to be more competitive than Cowan I under shaken conditions (t176 = −6.74, P < 0.0001), while it lost similarly against P. aeruginosa under viscous and static conditions (viscous: t174 = 0.78, P = 0.4350; static: t176 = −1.99, P = 0.0482). In contrast, JE2 was the most competitive S. aureus strain in our panel (Fig. 3, column 3), performing significantly better than the other two S. aureus strains under all conditions (see Table S2 for the full statistical analysis) and outcompeted P. aeruginosa under shaken and viscous conditions.

FIG 3.

Relative fitness ln(v) of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (PA) after 24-h competitions against three different S. aureus (SA) strains (Cowan I, 6850, and JE2) at three different starting frequencies (1:9, 1:1, and 9:1) and across three different environmental conditions (shaken, viscous, and static). Values of ln(v) < 0, ln(v) > 0, or ln(v) = 0 (dotted line) indicate whether P. aeruginosa lost, won, or performed equally well in competition against the respective S. aureus strain. The box plots show the median (boldface line) with the first and third quartiles. The whiskers cover 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) or extend from the lowest to the highest value if they fall within 1.5 times the IQR. Each strain pair/culturing condition/starting frequency combination was repeated 20 times (four experiments featuring five replicates each). Asterisks indicate whether the relative fitness of P. aeruginosa is significantly different from zero in a specific treatment (one-sample t tests with P values corrected for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate method; n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Detailed information on all statistical comparisons is provided in Table S3.

The competitive ability of P. aeruginosa depends on its starting frequency in the population.

We found that the starting frequency of the two competitors had varying but always significant effects on the competitive ability of P. aeruginosa (ANCOVA; shaken, F1,170 = 52.81, P < 0.0001; viscous, interaction with strain background, F2,168 = 10.05, P < 0.0001; static, F1,170 = 162.32, P < 0.0001). Under shaken conditions (Fig. 3, row 1), we observed that the relative fitness of P. aeruginosa increased when this bacterium was initially more common, following a positive frequency-dependent pattern. Under viscous conditions (Fig. 3, row 2), the same positive frequency-dependent effect was only observed when P. aeruginosa competed with JE2. In competition with Cowan I or 6850, we noted that the relative fitness of P. aeruginosa peaked at intermediate starting frequencies. Under static conditions (Fig. 3, row 3), we observed a pattern that was the opposite of the one seen under shaken conditions for all strain pair combinations. The relative fitness of P. aeruginosa decreased when this bacterium was initially more common, following a negative frequency-dependent pattern (see Table S2 for the full statistical analysis).

The competitive ability of P. aeruginosa is highest under static conditions.

Next, we compared the competitive outcomes among the different culturing conditions (shaken, viscous, and static) for each strain combination separately. For all strain combinations, the culturing condition significantly affected competition outcomes (ANCOVA; Cowan I, F2,168 = 461.73, P < 0.0001; 6850, F2,167 = 428.16, P < 0.0001; JE2, F2,168 = 199.95, P < 0.0001). In competition experiments with all three S. aureus strains, we found that the relative fitness of P. aeruginosa was significantly higher under static than shaken conditions (Cowan I, t174 = 19.99, P < 0.0001; 6850, t174 = 17.99, P < 0.0001; JE2, t174 = 15.39, P < 0.0001). In contrast, there were no significant differences in the relative fitnesses of P. aeruginosa between shaken and viscous conditions for Cowan I (t174 = 0.91, P = 0.3644) and JE2 (t174 = 0.82, P = 0.4117), while against 6850, P. aeruginosa was more competitive under viscous than shaken conditions (t174 = 3.53, P = 0.0005) (see Table S2 for the full statistical analysis).

Temporal dynamics between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus.

In the next experiment, we competed P. aeruginosa and S. aureus strains over 5 days under shaken conditions using the same three starting frequencies and by transferring cultures to fresh medium every 24 h. The aim of this experiment was to monitor the more long-term species dynamics and to assess whether stable coexistence between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus can arise.

In competition with Cowan I, we found P. aeruginosa to be the dominant species (Fig. 4a). It strongly increased in frequency already at day 1 under all starting frequencies and almost completely outcompeted Cowan I by day 3 (i.e., Cowan I remained below the detection limit). Thus, we could not observe coexistence between P. aeruginosa and Cowan I. In competition with 6850, we observed similar population dynamics (Fig. 4b). P. aeruginosa strongly increased in frequency from day 1 onwards at all starting frequencies, and after 3 days, the bacterial populations consisted almost entirely of P. aeruginosa. In only 10 out of 30 populations, 6850 managed to persist at very low frequencies by day 5 (<3% in nine cases and 13% in one case). In competition with JE2, we found community trajectories that were strikingly different from the other two strain combinations (Fig. 4c). First, we observed that JE2 was a strong competitor, keeping P. aeruginosa at bay in many populations during the first 24 h of the experiment. Following day 1, community dynamics followed positive frequency-dependent patterns. In all populations with intermediate or high P. aeruginosa starting frequencies, P. aeruginosa became the dominant species, and S. aureus was recovered at low frequency in only a minority of populations by day 5 (3 out of 20 at <10% of the population). In stark contrast, in populations where P. aeruginosa was initially rare, it did not increase in frequency, could not invade the S. aureus populations, and remained at a low frequency (<10%) throughout the 5 days.

FIG 4.

Multiday competitive dynamics between P. aeruginosa PAO1 (PA) and the three S. aureus strains, Cowan I (a), 6850 (b), and JE2 (c), under shaken conditions. Competitions started at three volumetric starting frequencies of P. aeruginosa:S. aureus (red, 1:9; blue, 1:1; green, 9:1). Community composition was monitored over 5 days with daily transfer of diluted cultures to fresh TSB medium. Strain frequencies were assessed using flow cytometry. The experiment was carried out two times with five replicates per treatment combination and experiment.

DISCUSSION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus frequently occur together in polymicrobial infections, where they cause severe host damage and lead to increased morbidity and mortality in patients (14, 50, 51). Consequently, there is high interest in understanding how P. aeruginosa and S. aureus interact and how their interactions may influence disease outcome (12, 15). While most previous studies have focused on molecular aspects (52, 53), here we examined how a set of ecological factors affect competitive interactions between the two species. Our study, carried out in an in vitro batch culture system, revealed that (i) the competitive ability of P. aeruginosa varied extensively as a function of the genetic background of S. aureus; (ii) there were strong frequency-dependent fitness patterns, including positive frequency-dependent relationships where P. aeruginosa could only dominate a particular S. aureus strain (JE2) when common but not when rare; and (iii) changes in environmental (culturing) conditions fundamentally affected the competitive balance between the two species. The key conclusion from our results is that ecology matters, and that variations in biotic and abiotic factors affect interactions between pathogenic bacterial species. This is most likely the case not only in in vitro systems but also in the context of polymicrobial infections.

P. aeruginosa has often been described as a dominant pathogen that is able to displace S. aureus in infections (21, 54–56). Our results support this view, as P. aeruginosa dominated over S. aureus under many conditions in 24-h and 5-day competition experiments (Fig. 3 and 4). However, P. aeruginosa did not always emerge as the winner, and its success significantly varied in response to the genetic background of S. aureus. Specifically, JE2 was the strongest competitor, followed by 6850 and Cowan I. While differences in monoculture growth performance can explain why P. aeruginosa dominates in many cases, they cannot explain the variation in competitive abilities among S. aureus strains, because the three S. aureus strains grew similarly under all conditions (Fig. 2). P. aeruginosa versus JE2 makes the strongest case for a mismatch between growth performance in monocultures versus mixed cultures, as P. aeruginosa grew significantly better than JE2 in monoculture under shaken conditions but typically lost the competition in mixed cultures in this environment (Fig. 2 and 3). This suggests that apart from resource competition via growth rate differences, other factors must contribute to the competitive ability of S. aureus strains toward P. aeruginosa. Such factors could include interference mechanisms. For example, it is known that genetically different S. aureus strains widely differ in virulence among each other (57–59).

Interestingly, we found that the competitive ability of our three S. aureus strains against P. aeruginosa correlated with their reported virulence level in infections (34, 36, 39). This indicates that factors important for S. aureus virulence (e.g., toxins or secreted enzymes) also are involved in interactions with competitor bacteria. For JE2 and related USA300 isolates, there are many genetic determinants known to be important for their success as opportunistic human pathogens (60). Among them are the cytotoxin Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), the arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME), and the phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) (61). Derivatives of PSMs have previously been shown to exhibit inhibitory activity against Streptococcus pyogenes (62). The authors of this work suggested that high production of PSMs benefits S. aureus not only in host colonization but also in competition against coinfecting pathogens. Thus, it seems plausible that the USA300 derivative JE2 deploys a similar mechanism against P. aeruginosa in our competition experiments. Strain 6850 showed intermediate competitiveness against P. aeruginosa. Like Cowan I, 6850 is an MSSA strain, but it is known to be more virulent than Cowan I and, therefore, likely produces certain substances that also could be important in competition with P. aeruginosa (34, 36). Conversely, Cowan I is known to have a nonfunctional accessory gene regulator (agr) quorum-sensing system (34). The agr controls most virulence determinants in S. aureus (63). If virulence determinants also played a role in interspecies competition, then this could explain why Cowan I turned out to be the least competitive S. aureus strain against P. aeruginosa.

It is important to note that we only manipulated the S. aureus and not the P. aeruginosa strain background, so we cannot draw conclusions on genotype-by-genotype interactions. Such interactions are likely to play a role, as evidenced by previous studies showing that genetically diverse P. aeruginosa clinical isolates widely differ in their ability to inhibit S. aureus (29, 64, 65). More recently, it has also been shown that S. aureus clinical isolates vary in their interactions with PA, from being highly sensitive to completely tolerant against P. aeruginosa-mediated effects (66). One aim of our future work is to follow up these proposed mechanistic leads and test some of the hypotheses outlined above to explain differences in the competitive abilities between S. aureus strains and P. aeruginosa.

Another insight from our experiments is that the competitive ability of P. aeruginosa often depended on its starting frequency in the population, and that the type of frequency-dependent interactions (positive or negative) varied across environmental conditions (Fig. 3). Our purpose was to compare three experimentally defined starting frequencies to mimic what is happening when a species is either rare (1:9), at parity with its competitor (1:1), or dominant (9:1). Under natural conditions, including infections, species frequencies could of course be more extreme, and invasion from a rare state could start at species frequencies that would be below the detection limit of our methods.

In our experiments, we observed that under static conditions, the relative fitness of P. aeruginosa declined when it was more common in the population, but P. aeruginosa still won at all frequencies. This pattern is common for a highly dominant species that drives a competitor to extinction (67). Its decline in relative fitness simply reflects the fact that room for further absolute frequency gains is reduced when a high frequency is already reached. In stark contrast, under shaken conditions, we found that the relative fitness of P. aeruginosa increased when it was more common in the population. Against Cowan I and 6850, this positive frequency-dependent fitness pattern did not affect the long-term community dynamics, and P. aeruginosa won at all frequencies (Fig. 4a and b). Against JE2, however, the 24-h competition data suggest that, in most cases, P. aeruginosa cannot invade populations when initially rare, and this is exactly what we observed in the long-term experiments: when its initial frequency was below 10%, P. aeruginosa did not increase in frequency, whereas it always fixed to 100% in the population or reached very high frequencies when initially occurring above 10%. There were two additional interesting observations on P. aeruginosa-JE2 long-term dynamics. First, there were no major changes in P. aeruginosa frequency relative to JE2 during the first 24 h (compatible with the competition assay data shown in Fig. 3), and clear positive frequency-dependent patterns only emerged from 48 h onwards. One possible explanation for this pattern is that P. aeruginosa is initially naive but then senses and mounts a more competitive response over time (68). Similarly, S. aureus might also respond, for example, through increased formation of small colony variants (SCVs), which are known to be induced by inhibitory exoproducts released by P. aeruginosa (22, 24). Second, one replicate (starting frequency, 1:1) did not follow the above rules: P. aeruginosa continuously dropped in frequency until day 4 (11%) and then sharply increased to 93% on day 5. This frequency zig-zag pattern is an indicator of antagonistic coevolution (69), where the spread of a beneficial mutation in one species (S. aureus) is followed by a counteradaptation in the competing species (P. aeruginosa). Therefore, it seems that such evolutionary dynamics can already occur within relatively short periods of time. This finding supports evidence from studies on clinical P. aeruginosa isolates that showed patterns of adaptations toward S. aureus favoring coexistence between the two species over time (29, 30).

Our results further show that the competitive ability of P. aeruginosa is profoundly influenced by environmental (culturing) conditions (Fig. 3). The largest differences arose between shaken and static culturing conditions, with P. aeruginosa being more competitive in the latter environment. P. aeruginosa is known to be metabolically versatile, it is motile, and it grows well under microoxic conditions (70, 71). Static conditions introduce strong oxygen and nutrient gradients, and our results from monoculture growth show that P. aeruginosa grows better under these conditions than S. aureus (Fig. 2). This is certainly part of the reason why P. aeruginosa ends up as the competition winner against all S. aureus strains under static conditions. With regard to medium viscosity, we initially hypothesized that increased spatial structure could temper competitive interactions and favor species coexistence, as competitors are spatially more segregated from each other (44, 72, 73). However, we found no support for this hypothesis, as the competitive ability of P. aeruginosa did not much differ between shaken and viscous environments. While the spatial structure, introduced through the addition of agar to the liquid growth medium, had significant effects on within-species social interactions in other study systems (67, 74), it did not appreciably affect the between-species interactions in our setup. One reason might be that the degree of spatial structure introduced (0.2% agar in TSB) was simply not high enough to see an effect. This could be especially true if toxins were involved in mediating interactions, such as small molecules that can freely diffuse and target competitors that are not physically nearby.

We argue that our results, even though they stem from an in vitro system, could have at least three important implications for our understanding of polymicrobial infections. First, we show that the biological details of the strain background matter and will determine which strain is dominant in a coinfection and whether coexistence between species is possible. Thus, we need to be careful not to overinterpret interaction data from a single P. aeruginosa-S. aureus strain pair and conclude that the specific details found apply to P. aeruginosa-S. aureus interactions in general. Second, there might be strong order effects, such that the species that infects a host first cannot be invaded by a later-arriving species. This scenario applied to the interactions between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus strain JE2, both of which were unable to invade populations of the other species from rare. Finally, local physiological conditions at the infection site, like the degree of spatial structure or oxygen supply, can shift the competitive balance between species. This suggests that infections at certain sites are more prone than others to polymicrobial infections or to experience ecological shifts from one pathogen to another. To sum up, we reiterate our message that the ecology of interactions between pathogens should receive more attention and may explain unresolved aspects of polymicrobial infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

We used the Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAO1 (75) as our P. aeruginosa reference strain and the Staphylococcus aureus strains Cowan I, 6850, and JE2 for all experiments (Table 1). To distinguish P. aeruginosa from S. aureus strains, we used a variant of our P. aeruginosa strain PAO1, which constitutively expresses the green fluorescent protein, from a single-copy gene (attTn7::ptac-gfp), stably integrated in the chromosome (76, 77). We chose the rich laboratory medium tryptic soy broth (TSB; Becton, Dickinson) for all our experiments, because it supports growth of all the strains used. Bacterial stocks were prepared by mixing 50% culture with 50% of an 85% glycerol solution and were stored at –80°C. For all experiments, overnight cultures were grown in 10 ml TSB in 50 ml falcon tubes for 16 h (±30 min) at 37°C and 220 rpm with aeration. After centrifugation and removal of the supernatant, we washed bacterial cells using 10 ml 0.8% NaCl solution and adjusted the OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) to obtain similar cell numbers per milliliter for each strain. All media, buffer, and washing solutions were sterilized by autoclaving at 121°C for 20 min and subsequently stored at room temperature in the dark. For all experiments, blanks were used to ensure the sterility of the media during experimentation.

Calculating number of doublings for each strain in monoculture.

To assess the number of doublings of each strain in monoculture, we grew our strains in TSB (or TSB plus 0.2% agar, respectively) under the same conditions and using the same starting OD600 as that for the competition experiments (see below). We serially diluted cells at the start (t0) and after 24 h (t24) and plated aliquots on TSB plus 1.2% agar. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C and colony-forming units (CFU) counted for both time points the following day. We estimated the number of doublings (D) for each strain as D = [ln(x24/x0)]/ln(2), where x0 and x24 are the initial and the final number of CFU/ml, respectively (23). We performed this experiment two times with three replicates per strain per experiment.

Competition experiments.

To initiate competitions, we mixed P. aeruginosa and S. aureus strain pairs at three different starting frequencies (1:9, 1:1, and 9:1) from washed and OD600-adjusted overnight cultures (described above). Competitions occurred in 24-well plates filled with 1.5 ml TSB per well. The starting OD600 of both mixed cultures and monocultures was 10−5. Monocultures of each strain served as controls in each experiment. We incubated plates for 24 h at 37°C under three different culturing conditions: shaken (170 rpm), viscous (170 rpm with 0.2% agar in TSB), and static. Before and after the 24-h competition period, we estimated the actual strain frequencies for each replicate using flow cytometry. We performed four independent experiments, each featuring five replicates for each strain/starting frequency/condition combination. A graphical representation of the competition workflow is provided in Fig. 1.

To monitor community dynamics over time, we set up competitions in the same way as that described above. After the first 24 h of competition, we diluted cultures 1:10,000 into fresh TSB medium. This process was repeated for five consecutive days. Strain frequencies were assessed using flow cytometry prior to and after each 24-h competition cycle. We carried out two independent experiments for each strain pair and starting frequency combination with 5 replicates per strain pair and frequency.

Flow cytometry to estimate relative species frequency.

We assessed the relative strain frequencies at the beginning and at the end of each competition using a BD LSR II Fortessa flow cytometer (flow cytometry facility, University of Zürich) and the FlowJo software (BD Biosciences) for data analysis. As our P. aeruginosa strain expresses a constitutive green fluorescent protein (GFP) tag, P. aeruginosa cells could unambiguously be distinguished from the GFP-negative S. aureus cells with a blue laser line (excitation at 488 nm) and the fluorescein isothiocyanate channel (emission: mirror, 505-nm longpass; filter, 530/30 nm) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Cytometer Setup and Tracking settings of the instrument were used for each experiment, and the threshold of particle detection was set to 200 V (lowest possible value). We diluted cultures appropriately in sterile-filtered 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher) and recorded 100,000 events with a low flow rate. The following controls were used for data acquisition in every experiment: (i) PBS blank samples (to estimate the number of background counts of the flow cytometer), (ii) untagged monocultures (negative fluorescence control, used to set a fluorescence threshold in FlowJo), and (iii) constitutive GFP-expressing monocultures (positive fluorescence control, set to 100% GFP-positive cells). Using our fluorescence threshold, we extracted the percentage of GFP-positive cells for each sample and scaled these values to the positive fluorescence control. The resulting percentage corresponds to the frequency of P. aeruginosa present in the respective replicate. Initial and final strain frequencies were used to calculate the relative fitness (v) of the focal strain P. aeruginosa as v = [at × (1 − a0)]/[a0 × (1 − at)], where a0 and at are the initial and final frequencies of P. aeruginosa, respectively (43). We ln-transformed all relative fitness values to obtain normally distributed residuals. Values of ln(v) > 0 or ln(v) < 0 indicate whether the frequency of the focal strain P. aeruginosa increased (i.e., P. aeruginosa won the competition) or decreased (i.e., P. aeruginosa lost competition) relative to its S. aureus competitor.

We know from previous experiments in our laboratory that, due to the GFP tag, our P. aeruginosa strain does have a slight fitness defect in competition with its untagged parental strain [ln(v) = −0.358 ± 0.13, mean ± 95% confidence interval; see reference 67]. As we consistently used the same GFP-tagged P. aeruginosa strain for all experiments in this study, results are fully comparable among treatments.

To test whether flow cytometry counts (measuring all viable and nonviable cells) correlated with CFU numbers (measuring only viable cells), we serially diluted and plated initial and final strain frequencies from competitions performed under shaken conditions for all three strain combinations on TSB plus 1.2% agar. We compared the obtained number of CFU with the flow cytometry counts from the same samples and found strong positive correlations for the strain frequency estimates between the two methods (Fig. S2). This means that flow cytometry adequately measures strain frequencies and that the two methods (flow cytometry and CFU counts) yield similar results.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed with R Studio version 3.6.1. We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s HSD to compare the number of doublings in monocultures of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. To test whether the relative fitness of P. aeruginosa varies in response to the S. aureus strain genetic background, starting frequency, and culturing conditions, we first built a factorial analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with the S. aureus strain genetic background and culturing conditions as factors and the starting frequency as the covariate. We further included an “experimental block” as an additional factor to account for variation between experiments. This full model yielded a significant triple interaction between S. aureus strain genetic background, starting frequency, and culturing condition. Therefore, we split the full model into a set of ANCOVA submodels, separated either by culturing condition (shaken, viscous, or static) or by S. aureus strain genetic background (Cowan I, 6850, or JE2). For post hoc pairwise comparisons between culturing conditions or S. aureus strains in the submodels, we removed experimental block as an additional factor from the model. To test whether P. aeruginosa relative fitness is significantly different from zero under a given strain/starting frequency/condition combination, we performed one-sample t tests and used the false discovery rate method to correct P values for multiple comparisons (78). To compare strain frequencies obtained by flow cytometry with those obtained by plating (CFU), we used Pearson correlation analysis. For all data sets, we consulted Q-Q plots and results from the Shapiro-Wilk test to ensure that our residuals were normally distributed. Summary tables for linear models and t tests used to analyze Fig. 2 and 3 can be found in the supplemental material (Tables S1 to S3).

Data availability.

All raw data sets have been deposited in the figshare repository (https://figshare.com/articles/2020_Niggli_etal_rawdata_figshare_xlsx/12620768/1).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Markus Huemer (University Hospital of Zürich) for providing S. aureus strains and the flow cytometry facility (University of Zürich) for technical support and maintenance of resources.

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 681295) to R.K. The illustration for Fig. 1 was created using BioRender.

S.N. and R.K. designed research, S.N. performed research, and S.N. and R.K. analyzed data and wrote the paper.

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stubbendieck RM, Vargas-Bautista C, Straight PD. 2016. Bacterial communities: interactions to scale. Front Microbiol 7:1234. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donaldson GP, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK. 2016. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:20–32. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Human Microbiome Project Consortium. 2012. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brogden KA, Brogden KA, Guthmiller JM, Guthmiller JM, Taylor CE, Taylor CE, Guthmiller JM, Guthmiller JM. 2005. Human polymicrobial infections. Lancet 365:253–255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17745-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters BM, Jabra-Rizk MA, O'May GA, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. 2012. Polymicrobial interactions: impact on pathogenesis and human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:193–213. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers GB, Hoffman LR, Carroll MP, Bruce KD. 2013. Interpreting infective microbiota: the importance of an ecological perspective. Trends Microbiol 21:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vos MGJ, Zagorski M, McNally A, Bollenbach T. 2017. Interaction networks, ecological stability, and collective antibiotic tolerance in polymicrobial infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:10666–10671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1713372114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rezzoagli C, Granato ET, Kümmerli R. 2020. Harnessing bacterial interactions to manage infections: a review on the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a case example. J Med Microbiol 69:147–161. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Short FL, Murdoch SL, Ryan RP. 2014. Polybacterial human disease: the ills of social networking. Trends Microbiol 22:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tashiro Y, Yawata Y, Toyofuku M, Uchiyama H, Nomura N. 2013. Interspecies interaction between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other microorganisms. Microbes Environ 28:13–24. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan RP, Dow JM. 2008. Diffusible signals and interspecies communication in bacteria. Microbiology 154:1845–1858. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/017871-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray JL, Connell JL, Stacy A, Turner KH, Whiteley M. 2014. Mechanisms of synergy in polymicrobial infections. J Microbiol 52:188–199. doi: 10.1007/s12275-014-4067-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubert D, Réglier-Poupet H, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Ferroni A, Le Bourgeois M, Burgel PR, Serreau R, Dusser D, Poyart C, Coste J. 2013. Association between Staphylococcus aureus alone or combined with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the clinical condition of patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 12:497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maliniak ML, Stecenko AA, McCarty NA. 2016. A longitudinal analysis of chronic MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa co-infection in cystic fibrosis: a single-center study. J Cyst Fibros 15:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limoli DH, Hoffman LR. 2019. Help, hinder, hide and harm: what can we learn from the interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus during respiratory infections. Thorax 74:684–692. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orazi G, Ruoff KL, O’Toole GA. 2019. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Increases the sensitivity of biofilm-grown Staphylococcus aureus to membrane-targeting antiseptics and antibiotics. mBio 10:e01501-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01501-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tognon M, Köhler T, Luscher A, Van Delden C. 2019. Transcriptional profiling of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus during in vitro co-culture. BMC Genomics 20:30. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5398-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cystic Fibrosis Trust. 2014. UK Cystic Fibrosis Registry annual data report 2018. Cystic Fibrosis Trust, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gjødsbøl K, Christensen JJ, Karlsmark T, Jørgensen B, Klein BM, Krogfelt KA. 2006. Multiple bacterial species reside in chronic wounds: a longitudinal study. Int Wound J 3:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2006.00159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malic S, Hill KE, Hayes A, Percival SL, Thomas DW, Williams DW. 2009. Detection and identification of specific bacteria in wound biofilms using peptide nucleic acid fluorescent in situ hybridization (PNA FISH). Microbiology 155:2603–2611. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.028712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mashburn LM, Jett AM, Akins DR, Whiteley M. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus serves as an iron source for Pseudomonas aeruginosa during in vivo coculture. J Bacteriol 187:554–566. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.2.554-566.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman LR, Déziel E, D'Argenio DA, Lépine F, Emerson J, McNamara S, Gibson RL, Ramsey BW, Miller SI. 2006. Selection for Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants due to growth in the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:19890–19895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606756104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison F, Paul J, Massey RC, Buckling A. 2008. Interspecific competition and siderophore-mediated cooperation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ISME J 2:49–55. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biswas L, Biswas R, Schlag M, Bertram R, Götz F. 2009. Small-colony variant selection as a survival strategy for Staphylococcus aureus in the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:6910–6912. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01211-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler E, Safrin M, Olson JC, Ohman DE. 1993. Secreted LasA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a staphylolytic protease. J Biol Chem 268:7503–7508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dalton T, Dowd SE, Wolcott RD, Sun Y, Watters C, Griswold JA, Rumbaugh KP. 2011. An in vivo polymicrobial biofilm wound infection model to study interspecies interactions. PLoS One 6:e27317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pastar I, Nusbaum AG, Gil J, Patel SB, Chen J, Valdes J, Stojadinovic O, Plano LR, Tomic-Canic M, Davis SC. 2013. Interactions of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in polymicrobial wound infection. PLoS One 8:e56846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tognon M, Köhler T, Gdaniec BG, Hao Y, Lam JS, Beaume M, Luscher A, Buckling A, Van Delden C. 2017. Co-evolution with Staphylococcus aureus leads to lipopolysaccharide alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ISME J 11:2233–2243. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michelsen CF, Christensen AMJ, Bojer MS, Høiby N, Ingmer H, Jelsbak L. 2014. Staphylococcus aureus alters growth activity, autolysis, and antibiotic tolerance in a human host-adapted Pseudomonas aeruginosa lineage. J Bacteriol 196:3903–3911. doi: 10.1128/JB.02006-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michelsen CF, Khademi SMH, Johansen HK, Ingmer H, Dorrestein PC, Jelsbak L. 2016. Evolution of metabolic divergence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa during long-term infection facilitates a proto-cooperative interspecies interaction. ISME J 10:1323–1336. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeLeon S, Clinton A, Fowler H, Everett J, Horswill AR, Rumbaugh KP. 2014. Synergistic interactions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus in an In vitro wound model. Infect Immun 82:4718–4728. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02198-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beaudoin T, Yau YCW, Stapleton PJ, Gong Y, Wang PW, Guttman DS, Waters V. 2017. Staphylococcus aureus interaction with Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm enhances tobramycin resistance. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 3:25. doi: 10.1038/s41522-017-0035-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orazi G, O’Toole GA. 2017. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alters Staphylococcus aureus sensitivity to vancomycin in a biofilm model of cystic fibrosis infection. mBio 8:e00873-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00873-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grundmeier M, Tuchscherr L, Brück M, Viemann D, Roth J, Willscher E, Becker K, Peters G, Löffler B. 2010. Staphylococcal strains vary greatly in their ability to induce an inflammatory response in endothelial cells. J Infect Dis 201:871–880. doi: 10.1086/651023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vann JM, Proctor RA. 1987. Ingestion of Staphylococcus aureus by bovine endothelial cells results in time- and inoculum-dependent damage to endothelial cell monolayers. Infect Immun 55:2155–2163. doi: 10.1128/IAI.55.9.2155-2163.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haslinger-Löffler B, Kahl BC, Grundmeier M, Strangfeld K, Wagner B, Fischer U, Cheung AL, Peters G, Schulze-Osthoff K, Sinha B. 2005. Multiple virulence factors are required for Staphylococcus aureus-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells. Cell Microbiol 7:1087–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balwit JM, van Langevelde P, Vann JM, Proctor RA. 1994. Gentamicin-resistant menadione and hemin auxotrophic staphylococcus aureus persist within cultured endothelial cells. J Infect Dis 170:1033–1037. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nimmo GR. 2012. USA300 abroad: global spread of a virulent strain of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:725–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thurlow LR, Joshi GS, Richardson AR. 2012. Virulence strategies of the dominant USA300 lineage of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 65:5–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00937.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rendueles O, Amherd M, Velicer GJ. 2015. Positively frequency-dependent interference competition maintains diversity and pervades a natural population of cooperative microbes. Curr Biol 25:1673–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Healey D, Axelrod K, Gore J. 2016. Negative frequency‐dependent interactions can underlie phenotypic heterogeneity in a clonal microbial population. Mol Syst Biol 12:877. doi: 10.15252/msb.20167033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levin BR. 1988. Frequency-dependent selection in bacterial populations. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 319:459–472. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1988.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross-Gillespie A, Gardner A, West SA, Griffin AS. 2007. Frequency dependence and cooperation: theory and a test with bacteria. Am Nat 170:331–342. doi: 10.1086/519860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kerr B, Riley MA, Feldman MW, Bohannan B. 2002. Local dispersal promotes biodiversity in a real-life game of rock-paper-scissors. Nature 418:171–174. doi: 10.1038/nature00823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Gestel J, Weissing FJ, Kuipers OP, Kovács ÁT. 2014. Density of founder cells affects spatial pattern formation and cooperation in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. ISME J 8:2069–2079. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weigert M, Ross-Gillespie A, Leinweber A, Pessi G, Brown SP, Kümmerli R. 2017. Manipulating virulence factor availability can have complex consequences for infections. Evol Appl 10:91–101. doi: 10.1111/eva.12431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spiers AJ, Bohannon J, Gehrig SM, Rainey PB. 2003. Biofilm formation at the air-liquid interface by the Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 wrinkly spreader requires an acetylated form of cellulose. Mol Microbiol 50:15–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borer B, Tecon R, Or D. 2018. Spatial organization of bacterial populations in response to oxygen and carbon counter-gradients in pore networks. Nat Commun 9:769. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03187-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niggli S, Kümmerli R. 2020. Strain background, species frequency and environmental conditions are important in determining population dynamics and species co-existence between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.04.21.052670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Limoli DH, Yang J, Khansaheb MK, Helfman B, Peng L, Stecenko AA, Goldberg JB. 2016. Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa co-infection is associated with cystic fibrosis-related diabetes and poor clinical outcomes. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 35:947–953. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2621-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Serra R, Grande R, Butrico L, Rossi A, Settimio UF, Caroleo B, Amato B, Gallelli L, De Franciscis S. 2015. Chronic wound infections: the role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 13:605–613. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1023291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hotterbeekx A, Kumar-Singh S, Goossens H, Malhotra-Kumar S. 2017. In vivo and In vitro interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus spp. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:106. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nguyen AT, Oglesby-Sherrouse AG. 2016. Interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus during co-cultivations and polymicrobial infections. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:6141–6148. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7596-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Machan ZA, Pitt TL, White W, Watson D, Taylor GW, Cole PJ, Wilson R. 1991. Interaction between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus: description of an anti-staphylococcal substance. J Med Microbiol 34:213–217. doi: 10.1099/00222615-34-4-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pernet E, Guillemot L, Burgel PR, Martin C, Lambeau G, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Sands D, Leduc D, Morand PC, Jeammet L, Chignard M, Wu Y, Touqui L. 2014. Pseudomonas aeruginosa eradicates Staphylococcus aureus by manipulating the host immunity. Nat Commun 5:5105. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Filkins LM, O’Toole GA. 2015. Cystic fibrosis lung infections: polymicrobial, complex, and hard to treat. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.King JM, Kulhankova K, Stach CS, Vu BG, Salgado-Pabón W. 2016. Phenotypes and virulence among Staphylococcus aureus USA100, USA200, USA300, USA400, and USA600 clonal lineages. mSphere 1:e00071-16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00071-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tuchscherr L, Pöllath C, Siegmund A, Deinhardt-Emmer S, Hoerr V, Svensson CM, Figge MT, Monecke S, Löffler B. 2019. Clinical S. aureus isolates vary in their virulence to promote adaptation to the host. Toxins 11:135. doi: 10.3390/toxins11030135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Montgomery CP, Boyle-Vavra S, Adem PV, Lee JC, Husain AN, Clasen J, Daum RS. 2008. Comparison of virulence in community‐associated methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus pulsotypes USA300 and USA400 in a rat model of pneumonia. J Infect Dis 198:561–570. doi: 10.1086/590157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Diep BA, Gill SR, Chang RF, Phan TH, Chen JH, Davidson MG, Lin F, Lin J, Carleton HA, Mongodin EF, Sensabaugh GF, Perdreau-Remington F. 2006. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 367:731–739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watkins RR, David MZ, Salata RA. 2012. Current concepts on the virulence mechanisms of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol 61:1179–1193. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.043513-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joo HS, Cheung GYC, Otto M. 2011. Antimicrobial activity of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is caused by phenol-soluble modulin derivatives. J Biol Chem 286:8933–8940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheung AL, Bayer AS, Zhang G, Gresham H, Xiong YQ. 2004. Regulation of virulence determinants in vitro and in vivo in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 40:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baldan R, Cigana C, Testa F, Bianconi I, De Simone M, Pellin D, Di Serio C, Bragonzi A, Cirillo DM. 2014. Adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis airways influences virulence of Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and murine models of co-infection. PLoS One 9:e89614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Radlinski L, Rowe SE, Kartchner LB, Maile R, Cairns BA, Vitko NP, Gode CJ, Lachiewicz AM, Wolfgang MC, Conlon BP. 2017. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoproducts determine antibiotic efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Biol 15:e2003981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bernardy EE, Petit RA III, Raghuram V, Alexander AM, Read TD, Goldberg JB. 2020. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from cystic fibrosis patient lung infections and their interactions with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 11:e00735-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00735-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leinweber A, Inglis FR, Kümmerli R. 2017. Cheating fosters species co-existence in well-mixed bacterial communities. ISME J 11:1179–1188. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cornforth DM, Foster KR. 2013. Competition sensing: the social side of bacterial stress responses. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:285–293. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang QG, Buckling A, Ellis RJ, Godfray H. 2009. Coevolution between cooperators and cheats in a microbial system. Evolution 63:2248–2256. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Valot B, Guyeux C, Rolland JY, Mazouzi K, Bertrand X, Hocquet D. 2015. What it takes to be a Pseudomonas aeruginosa? The core genome of the opportunistic pathogen updated. PLoS One 10:e0126468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolfgang MC, Kulasekara BR, Liang X, Boyd D, Wu K, Yang Q, Miyada CG, Lory S. 2003. Conservation of genome content and virulence determinants among clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:8484–8489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832438100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hyun JK, Boedicker JQ, Jang WC, Ismagilov RF. 2008. Defined spatial structure stabilizes a synthetic multispecies bacterial community. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:18188–18193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807935105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lowery NV, Ursell T. 2019. Structured environments fundamentally alter dynamics and stability of ecological communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:379–388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811887116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Refardt D, Bergmiller T, Kümmerli R. 2013. Altruism can evolve when relatedness is low: evidence from bacteria committing suicide upon phage infection. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 280:20123035. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FS, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou M, Garber RL, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody LL, Coulter SN, Folger KR, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong GK, Wu Z, Paulsen IT, Reizer J, Saier MH, Hancock RE, Lory S, Olson MV. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959–964. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Choi KH, DeShazer D, Schweizer HP. 2006. mini-Tn7 insertion in bacteria with multiple glmS-linked attTn7 sites: example Burkholderia mallei ATCC 23344. Nat Protoc 1:162–169. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rezzoagli C, Granato ET, Kümmerli R. 2019. In-vivo microscopy reveals the impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa social interactions on host colonization. ISME J 13:2403–2414. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0442-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a pratical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B 57:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw data sets have been deposited in the figshare repository (https://figshare.com/articles/2020_Niggli_etal_rawdata_figshare_xlsx/12620768/1).